Abstract

This paper applies institutionalist theories to an exploration of continuity and change in the Italian labor immigration regime between 1990 and 2020. It asks why the regime has remained largely unchanged since the 1990s and investigates changes in regulatory settings since 2008. The explanation for the reproduction and inertia of the regime encompasses a logic of appropriateness, institutional functional complementarity and the political weakness of opposition to the status quo. The restrictions placed on labor immigration since 2008 are explained by economic and humanitarian crises and the evolution of migratory flows to Italy, which has provided alternative sources of labor.

Introduction

International migration is one of the most politically contested phenomena of the 21st century. However, continuity and change in immigration policies is yet to be fully understood; in part, because an institutionalist perspective has not been applied to these aspects of immigration policy.

Mainly associated with studies of capitalism and welfare states, institutionalism accounts for the longevity of suboptimal institutions and presents taxonomies and theories of institutional change (see e.g., Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009). The immigration policy literature, conversely, includes a small number of studies accounting for regulatory continuity, while analyses of immigration policy reforms generally do not adequately specify the magnitude of regulatory change and its effects. Furthermore, accounts of immigration restrictions have focused on economic and political determinants, largely overlooking the influence of other gradual, exogenous sources of change.

In this article, I apply insights from institutionalism to continuity and change in the Italian labor immigration regime. Italy has been one of the main destinations for migrants in Europe since the 1990s and until the Great Recession of 2008, this movement was largely composed of labor inflows (Perna, Citation2019). The labor immigration regime—the system managing the admission of workers from outside of the European Union (EU)—has long been described as dysfunctional (Baldwin Edwards, Citation1998; Bonizzoni, Citation2018; Colombo & Dalla-Zuanna, Citation2019; Finotelli & Sciortino, Citation2009; Salis, Citation2012; Sciortino, Citation2009). While labor immigration policies are commonly characterized by implementation gaps—a lack of correspondence between policy outputs (i.e., laws and regulations) and their implementation (Czaika & de Haas, Citation2011)—the Italian regime is distinguished by a particularly large discrepancy between the regulatory framework and the actual modus operandi of the system. The regulatory system is largely based on annual quotas (quantitative ceilings) of foreign workers, who must be offered a job in Italy whilst they are still resident abroad before being admitted to work in the country. In reality, the system has largely involved ex-post regularization, where non-EU migrants come to Italy on tourist visas or irregularly, find a job and wait to be regularized, either within the annual quota system for the admission of non-EU workers or via a mass regularization procedure.

This paper seeks to ascertain the magnitude of change characterizing the Italian labor immigration regime between 1990 and 2020 and to explain both continuity and change. In particular, I ask: (1) What was the magnitude of change between the 1990s-early 2000s? (2) What explains regime inertia after 2002? (3) What was the magnitude of change after 2008? (4) What explains the changes introduced after 2008? I apply institutionalist categories and theories (Gerschewski, Citation2021; Hall, Citation1993; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005) to these questions. I triangulate secondary literature, parliamentary debates, media accounts, elite interviews and data on immigration, employment, quotas and residency; conducting thematic analysis on the qualitative data with the aim of identifying underlying logics, contextual drivers and constraints to reform.

The regime, in particular the primary instrument of annual quotas and the rule of admission from abroad on the basis of a job offer,Footnote1 is characterized by considerable longevity. My analysis of reproduction and inertia is informed by institutionalist theories of legitimation, functionalism and above all, power (see e.g., Campbell, Citation2004, Citation2009; Mahoney, Citation2000; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009). However, while the regulatory regime remains fundamentally the same, the instrument settings have been altered since the Great Recession, making the system increasingly selective, both quantitatively and qualitatively. This reflects a change in the overall goal of the system: in particular, reducing the volume of non-EU legal labor immigration and relying more on foreign worker ‘functional equivalents’. This rather dramatic change in goal has exogenous sources; the economic and refugee crises, and the related rise of the radical right, as well as the evolution of migratory flows to Italy, which has provided alternative sources of labor.

The next section of the article provides an overview of the immigration policy and institutionalist perspectives on continuity and change. The following section describes my methodology. I then briefly summarize the existing literature on the Italian case. The following two sections present my findings with regard to change and continuity between the 1990s and 2008 and in the period after 2008. My conclusions are presented in the last section.

Theoretical bases

Explaining regime stability

The immigration policy literature has a strong focus on change (Devitt forthcoming). Studies of immigration policy inertia, on the other hand, have focused on the EU level (see e.g., Guiraudon, Citation2018; Hadj Abdou & Pettrachin, Citation2022).

Once institutions are established, they tend to be sticky (Sydow & Koch, Citation2009) and the term ‘path dependence’ implies that the development of institutions is inhibited by the direction taken at their establishment (Mahoney, Citation2000). In sociology and political science, institutional path dependence has been accounted for from various perspectives, including the legitimation, functionalist and power explanations (Mahoney, Citation2000; Mahoney & Thelen, 2009; Campbell, Citation2004).

Legitimation, functionality and power

Sociological institutionalists emphasize rule-based action and policymakers’ use of criteria of similarity and congruence in selecting regulatory instruments, rather than conscious calculations of costs and benefits. Furthermore, actors can perceive an institution as legitimate, due to socialization into particular logics of appropriateness, and maintain it on that basis, rather than because they stand to gain from continuity (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Olsen & March, Citation2004). In this vein, policymakers’ actions may be, at least partially, based on logics of appropriateness including congruence with other ‘reputable’ regimes and ideas of fairness and normality. Institutions can also come to be taken for granted.

In functionalist accounts of path dependence, on the other hand, while their origins may be contingent, institutions become embedded in a larger system and serve a particular function which complements other parts of the system. This institutional complementarity explains institutional endurance (Ebbinghaus, Citation2005; Hall & Soskice, Citation2001; Mahoney, Citation2000). This perspective provides the expectation that policymakers/stakeholders may perceive an apparently dysfunctional institution as serving a function in the overall system.

Finally, the power-centred approach, favored by historical institutionalists, sees institutions as the result of political struggles and accounts for institutional longevity on the basis that a group benefitting from the status quo has enough power to reproduce the institution, even when most groups prefer to change it (Mahoney, Citation2000; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009). Furthermore, when actors’ ideas become established rules or frames, this ‘ideational power’ affects the capacity of other actors to promote new ideas (Schmidt Citation2017). If power is the explanation for institutional continuity—as has been argued in the case of EU migration policy (Guiraudon, Citation2018)—policymakers/stakeholders may maintain that reform has been impeded by the political dominance of particular groups and their ideas.

Rule-breaking

Institutionalists’ encompassing definition of institutions and work on rule-breaking provide further insight into institutional longevity. In academic discussions of gaps between immigration policies and their outcomes, precise definitions of what constitutes an immigration ‘policy’ or ‘regime’ are often lacking (Cvajner et al., Citation2018). Scholars have tended to focus on whether laws, regulations and measures—the policy on paper—meet their objectives. On the other hand, institutionalists define institutions as formal and informal rules and procedures which structure conduct (Campbell, Citation2004; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009). Institutions are, furthermore, argued to be often ill-conceived and ambiguous and thus subject to interpretation and contestation. For example, ‘slippage’ and expansive interpretations can occur when bureaucracies do not follow the letter of the law or interpret ambiguous rules (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009).

While such noncompliance has been conceived of as a source of endogenous institutional change (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009), I posit that it does not necessarily precipitate change and the formal system and informal rule-breaking practices can continue to co-exist indeterminately. Indeed, informal practices can arguably ensure the survival of the formal framework over a long period of time.

Exploring institutional change

The magnitude of change

Recent analyses of the openness or restrictiveness of immigration regulations and the direction of policy change (de Haas et al., Citation2018; Helbling et al., Citation2017) are informative regarding comparative restrictiveness across space and time. However, the conceptualization of the magnitude of policy change could be more developed. In an effort to take the level of change into account, de Haas et al weighted policy changes across 45 countries since 1945 with regards to the degree of departure from preexisting policies on a scale from ‘fine tuning’ to ‘major change’ (2018). However, as objective criteria for each level of change was not provided, it is unclear what constitutes each level on the scale.

The institutionalist literature is insightful here. For example, Hall’s distinction between first, second and third order change in his account of policy paradigms (1993) is useful in analyzing the extent of change. First order change involves altering policy settings, such as the rate at which a welfare benefit is paid, while second order change involves altering policy instruments, for example, welfare benefits or programmes. Finally, third order change entails change in settings, instruments and the goals behind the policy and represents a rupture of an existing paradigm. In another example of taxonomizing institutional change, Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005) argued that institutional change is not always dramatic and identified patterns of gradual change, including ‘layering’; when new layers are grafted onto existing institutions, and may eventually become dominant. This type of change does not invoke the same level of opposition as wholesale institutional displacement; representing stealthy transformational change.

It is also important to take into account policy implementation and the effects of changes. Indeed, a narrow focus on legislative reforms, does not provide us with a holistic understanding of change over time, as the practice and reform outcomes can be rather different to what is on paper and in discourse (Lahav & Guiraudon, Citation2006).

Explaining labor immigration policy change

The main determinants of shifts toward more restrictive immigration policies discussed in the literature are economic crises and rises in unemployment, the influence of public opinion, and the radical right. Regarding economic conditions, however, Natter et al (Citation2020) recently found that unemployment levels had no effect on immigration policy in 21 countries since the 1970s, perhaps due to continuing demand for migrant workers in jobs unattractive to native workers. Negative public attitudes toward immigration can induce governments to emit ‘control signals’ by publicizing harsher policies with regards to ‘unwanted migrants,’ thereby providing more scope to liberalize entry for other migrant categories (Wright, Citation2014). Public attitudes tend to be fairly stable and their influence often varies according to the degree of political salience of the immigration issue (Afonso & Devitt, Citation2016; Lutz, Citation2019). While, the radical right has been argued to have limited influence on government policies (Helbling et al., Citation2017; Lutz, Citation2019), some parties have spearheaded restrictive immigration policy changes and influenced center right positioning on immigration (Hadj Abdou et al., Citation2022; Zincone, Citation2006).

Applying institutionalist work on change to immigration regimes provides the expectation of additional sources of change. In the institutionalist literature, exogenous sources of change are often associated with dramatic ruptures, exemplified by the impact of financial crises or war. However, it has been argued that gradual, exogenous change, for example, demographic developments, can also bring about gradual institutional change (Campbell, Citation2004; Gerschewski, Citation2021). Along similar lines, the substitution effect of rising numbers of non-labor migrant categories may result in more restrictive labor immigration policies.

Research design

To address these questions of what constitutes and explains continuity and change in immigration regimes, I explore reproduction, inertia and change in the Italian labor immigration regime between 1990 and 2020. This single country case study allows for deeper analysis than cross-national research; generating insights which can be investigated in other contexts (Bennett & George, Citation2005).

The Italian case has been selected on the basis that EU member states retain almost exclusive responsibility for regulating labor immigration and Italy was one of the main destinations for labor migrants in Europe in the first decade of the 21st century (OECD, Citation2008).Footnote2 Moreover, the Italian regime is characterized by a particularly large discrepancy between the regulatory framework and the modus operandi of the system, and, like many others, is characterized by both path dependence and change (Bonetti et al., Citation2022; Bonizzoni, Citation2018).

I apply institutionalist categorisations of change, taking into account the implementation and effects of regulatory changes, in particular on opportunities to ‘enter’ Italy for work, to ascertain the magnitude of change over time. I then employ institutionalist theories to explain periods of continuity and change. The timings of various legislative developments, reform efforts and changes to instrument settings between 1990—when the first piece of legislation on labor immigration was passed—and 2020 are contextualized in order to identify the confluence of actors and events shaping them. While it is challenging to identify the motivations of partisan actors, where possible, the logic shaping policy preferences and choices is discussed.

Qualitative sources include secondary scholarly accounts, parliamentary debates surrounding relevant legislative initiatives between 1990 and 2020, media accounts of political debates, and semi-structured interviews with Italian policymakers and key informants conducted—virtually—in 2021 (see ). The interviews provided insights into the context and logics shaping policy choices and preferences. They were conducted in Italian, transcribed verbatim and translated into English. Thematic analysis was conducted on the qualitative data in order to identity common themes and to ascertain the significance of factors highlighted in migration policy studies and institutionalist scholarship in explaining re-production, inertia and change. The study also employed OECD and EUROSTAT migration and employment statistics, Italian ministerial data on quotas and Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) data on residency and citizenship.

Table 1. Interviews.

Scholarship on the entry criteria of Italian labor migration regime

The existing literature on the entry criteria of the Italian labor migration regime accounts for increasingly restrictive legislation between the 1990s and early 2000s, rather than the subsequent inertia of the system (however, see Bonetti et al for a recent discussion of politicization and inertia (2022)). The restrictive features of the regime are largely accounted for by political pressures and a logic of instrumentality. The 1990s laws were stimulated by the perceived failure of existing regulatory frameworks and European pressures to bring Italian legislation in line with its (future) SchengenFootnote3 partners (Magnani, Citation2012; Piro, Citation2020; Zincone, Citation2006). The laws of the 1990s and early 2000s were also formulated in the context of the increasing politicization of immigration within the fragmented, unstable party system (Bontempelli, Citation2009; Finotelli & Sciortino, Citation2009; Massetti, Citation2015).

The more limited literature on changes to the entry criteria of the Italian labor migration regime since the economic crisis of 2008 has emphasized economic conditions, a rise in unemployment and reduced demand for migrant workers in explanations for the shift toward a more restrictive system (Caponio & Cappiali, Citation2018; Einaudi, Citation2018; Pastore, Citation2016).

Explaining the reproduction and inertia of the Italian labor immigration regime

Regime reproduction (1990–2002)

The legislative basis for the quota instrument and rule of admission on the basis of a job offer is in DPRFootnote4 No. 39/1990 (known as the ‘Martelli law’) and DPR No. 40/1998 (known as the ‘Turco-Napolitano law’), both passed during center-left coalition governments. The DPR No.189/2002 (known as the ‘Bossi-Fini law’), produced by a center-right coalition government, amended the DPR No. 40/1998, leaving the regime substantially intact.

DPR No. 39/1990 introduced the quota mechanism, though quotas for foreign workers were not established until the mid-1990s. Despite the retention of the resident labor market test,Footnote5 entry was not only dependent on having a job offerFootnote6 but could be allowed on the basis of sufficient means or the guarantee of associations or individuals that they could provide accommodation, financial support and cover the cost of the migrant’s return journey.

DPR No. 40/1998 made the key mechanism of annual quotas compulsory, while abolishing the resident labor market test, and re-introduced the rule of recruitment of migrant workers from abroad on the basis of a job offer. The law also introduced a sponsored job seeker’s permit within the annual quotas.

DPR No. 189/2002 abolished the job seeker’s permit and made the application procedure more cumbersome with the introduction of a unified contract of employment and residence and the reintroduction of the resident labor market test. Migrants would only be allowed entry for work if they already had a contract of employment and employers would need to demonstrate adequate accommodation for the migrant and guarantee the cost of the return journey. Residence permits had to be renewed more frequently and the risk of becoming irregular rose; unemployment was only permitted for 6 months, as opposed to 12 months previously (Zincone, Citation2006).

DPR No. 189/2002 represents significant restrictive change with regards to legal entry requirements, the maintenance of legal status and above all the political framing of immigration, which was henceforth discussed as an issue of security and public order (Ambrosini & Triandafyllidou, Citation2011; Caponio & Cappiali, Citation2018; Geddes, Citation2008). However, while this law undoubtedly contributed to a rise in irregular status, the entry and renewal requirements were implemented more softly than the law prescribed. For example, employers had to just indicate accommodation, without guaranteeing its availability; even if an EU citizen were available, the employer could still confirm the hiring of a non-EU worker; and the rule that foreign workers who become unemployed would have little chance to renew residence permits was never strictly implemented (Einaudi, Citation2007; Finotelli & Sciortino, Citation2009; Tuckett, Citation2015).

Relating this to Streeck and Thelen’s (Citation2005) work on the magnitude and types of institutional change, with an eye to the implementation and effect of changes, DPR No. 40/1998’s introduction of the job seeker permit is an instance of layering, while DPR No. 189/2002’s removal of that permit option is a case of institutional displacement. As we will see below, however, the job seeker permit represented a small proportion of permits and consequently, its elimination did not have a significant impact on inflows. In relation to Hall’s typology of change (1993), DPR No. 189/2002’s addition of conditions with regards to permit applications is a case of first order change. However, these changes were implemented more softly than prescribed. This law did not then, according to the institutionalist literature, and in line with some existing studies of Italian immigration policy (Ambrosetti & Paparusso, Citation2014; Zincone, Citation2006), represent a rupture of the existing regulatory paradigm of quotas, in-country recruitment and ex-post regularization. It did, however, make the existing regime more rigid and it can be argued to have embodied paradigmatic change in public discourse on immigration, which as we will see has had implications for regime reform efforts. Continuity is also evidenced by the fact that the quotas for labor immigrants were not significantly reduced following the law and were notably expanded soon after during a right wing government (see ).

A logic of appropriateness

As noted above, the restrictive features of the regime are largely accounted for in the literature by political pressures and a logic of instrumentality. However, logics of appropriateness can also be discerned in the choice of regulatory instruments in the 1990s.

Indeed, interviews with relevant left-leaning policymakers—two of whom were key players in the establishment of the regime in the 1990s—conducted long after the laws were formulated, suggest that logics of appropriateness and puzzling over the best solutions (Heclo, Citation1974) shaped policymakers’ choice of instruments. Claudio Martelli’s account of his rationale in formulating DPR No. 39/1990 is an example of how in puzzling over the best policy, contradictory ideas of appropriateness and feasibility can co-exist:

The law basically said those with accommodation and a job can come to Italy…and now when I hear claims that these are Nazi measures… if not where are they going to stay and what are they going to do…it seems fair that there are these conditions…obviously this doesn’t mean that everything always has to be so perfect, we are not German…and I thought if there wasn’t this, what could there be…I suggested that when a foreigner comes to live in Italy, he should be in some way adopted by the new country… there has to be an Italian person who guarantees and looks after (him)…(Tondelli, Citation2018)

With regards to the quotas, there was the precedent of the Martelli law, it was a pretty common system in other European countries, a pretty normal system… Admitting migrants with a job offer from abroad also…We knew we were in the European context…we aligned ourselves with this norm common in other European countries with significant immigration, but, finding it inadequate, we introduced the job seeking permit… (Interview 3)

Accounting for regime inertia after 2002

The functionalist explanation

While a logic of appropriateness appears to have partly influenced the establishment of the regime in the 1990s, analysis of parliamentary debates on immigration system reform after 2002 and interview data did not produce observations that policymakers take the regime for granted (see the power explanation section). But perhaps there is political consensus that, despite its apparent contradictions, it is a functioning solution for the Italian context.

Indeed, it could be asserted that until the Great Recession, the regime, according to an encompassing institutionalist perspective, represented a compromise between political, labor market and administrative realities. The whole labor immigration regime—including its informal parts—functioned according to the political goal of giving an appearance of tight control over immigration, the socio-economic goal of providing foreign labor for Italian households and small firms, and the reality of a weak administrative capacity.

Indeed, the story of the Italian labor immigration regime is largely one about the challenging task of managing the entry of foreign workers for employment in low skilled work in small firms and households. There is a considerably higher proportion of immigrants in low skilled jobs in Italy compared to northern Europe (OECD, Citation2015). Moreover, most migrant workers in Italy are employed in small firms and households, reflecting the predominance of micro firms in the Italian economy and an inadequate public care infrastructure (Devitt Citation2018, Pastore, Citation2016). Households and small businesses with low skilled labor needs are generally ill-equipped to begin a process of searching for a low skilled worker abroad, outside of exploring existing employees’ networks (OECD, Citation2009b). This can be further understood in the context of comparatively high levels of informal work. Indeed, the informal economy accounts for about a quarter of Italian GDP and is viewed as acceptable practice in the context of relatively high labor taxes and social contributions and the low profitability of small firms (Devitt, Citation2018).

The Italian administration has a questionable capacity to implement regulations as prescribed. Indeed, the issuing of quota decrees and permits is so delayed that the system can only work as a regularization as opposed to managing urgent business needs (Finotelli & Sciortino, Citation2009; Salis, Citation2012). Despite all the trappings of the French Napoleonic tradition, the Italian mode of governance is described as interventionist but inefficient (OECD, Citation2009a). A lack of administrative staff, weak coordination, high levels of discretion, low salaries, corruption and cronyism contribute to inefficient procedures (Finotelli & Echeverrıa, Citation2017; Tuckett, Citation2015).

A technical advisor to the General Directorate of Immigration and Integration policies (GDIIP) of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs highlighted various implementation challenges relating to the structure and culture of the labor market and administrative capacity:

We tried them all, for example firms training people in countries of origin but it didn’t work…The problem is the labour market culture…Most enterprises are very small, they don’t have a corporate culture. There is also an enormous problem with the functioning of the administrative machine. (Interview 2)

The non-explicit flexibility mechanism of continual regularisations is the reason the system has been able to last so long. Without that the restrictive system of labour migration quotas would have collapsed under the pressure of the presence of illegal migrant workers. (Interview 1)

The Power explanation

If Italian policymakers generally believe that the existing regime is functional to the specificity of the Italian political, administrative and labor market context, one could expect few attempts to reform it. However, while some on the right argue that the system is too lax (Interviews 1, 4), the idea of permitting foreign nationals to enter Italy and then find employment has long been viewed by some left-leaning policymakers as best suited to the specific needs of the Italian labor market. This mode of entry was enshrined in instances of layering in DPR No. 39/1990 and DPR No. 40/1998 and ever since its displacement with the DPR No. 189/2002, it has been re-proposed by left-leaning politicians.

A one-year job-seeker permit was introduced with DPR No. 40/1998, on the condition that an NGO, public authority or person resident in Italy, the so-called ‘sponsor,’ could guarantee the foreign national’s maintenance while s/he searched for work and repatriation costs. However, the instrument was viewed as an experiment and the center-left government only provided 30,000 job seeker slots in the annual quotas between 1999 and 2001 (Bontempelli, Citation2009)(Interviews 1, 3). It received harsh criticism from the center right (Interview 3) and was abolished by the next center-right government with the argument that the permits were being used by migrants to bring extended family to Italy and that it had led to employment in the black economy and criminal activities (Camera dei Deputati, Citation2002; Einaudi, Citation2007).

Center-left proposals to reform the immigration system, including the re-introduction of a job seeker permit, have been made in every legislature since DPR No. 189/2002 was passed. However, Italian politics has been beset by short-lived government coalitions (Massetti, Citation2015) and the center-left has not had a strong majority since 2001 (Interview 1). Furthermore, since DPR No. 189/2002, the public debate on immigration became increasingly security-orientedFootnote7 (Ambrosini & Triandafyllidou, Citation2011; Magnani, Citation2012) and tended to focus on the contrasting of undocumented immigration, while it moved to humanitarian inflows after 2011 (McMahon, Citation2018; Salis, Citation2012). Public narratives criminalizing migration have bolstered restrictive policy (Pannia, Citation2021) (though not its implementation or outcome); reducing the scope for actors with more liberal views on migration to gain support.

The 2006 election ushered in a heterogenous center-left coalition and a government bill to reform the immigration and integration regime, Bill No. 2976 of 2007, included the re-introduction of the sponsored job seeking permit. The Bill had support in government and in the Ministry of Interior, partly as Minister for the Interior Giuliano Amato, a respected member of the center-left, was fronting it. However, it elicited strong opposition from the center-right , who argued that it would lead to an increase in undocumented migration. The government was, in any case, short-lived and fell before the bill was debated in Parliament (Massetti, Citation2015)(Interview 4).

Subsequent proposals to re-introduce a job seeker permit have faced veto points in the context of wide, heterogenous coalitions, including right leaning parties (Interviews 1, 2). Furthermore, the economic context since the Great Recession and the significant levels of humanitarian migration after 2011 have made the liberalization of entry rules politically unappealing (Geddes & Pettrachin, Citation2020)(Interviews 1, 2, 4). More recently, the revitalized League under Matteo Salvini became the dominant political party in Italy on the back of strong rhetorical opposition to immigration (Geddes & Pettrachin, Citation2020). The most recent proposal to reform the system, which includes abolishing annual quotas and introducing a job seeker permit, emanates from a popular movement called ‘I was foreign—humanity that does good’ established in 2017, involving various pro-migrant associations and trade unions. It has been blocked at the parliamentary committee stage due to a lack of support on the center right and among some members of the Democratic Party (Interview 5). The latter have had a preeminent focus on refugees and have also been influenced by the ‘culture of fear’ around migration, produced by the right (Interviews 2, 3, 4, 6).

In sum, a logic of appropriateness can be discerned in the rationale for the establishment of the regime in the 1990s but its subsequent inertia is primarily explained by the inability of the opposition to the status quo to reform the system. At the same time, there is some evidence that the informal elements of the regime allowed it to function according to political imperatives and labor market and administrative realities, which partly explains the low pressure for reform, at least until the period following the Great Recession.

Changes to the regime since the Great recession

The magnitude of change

While the framework of the Italian labor migration regime has remained intact over the past decade, changes have been made within these parameters. The system has become increasingly selective, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

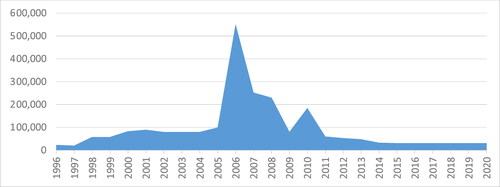

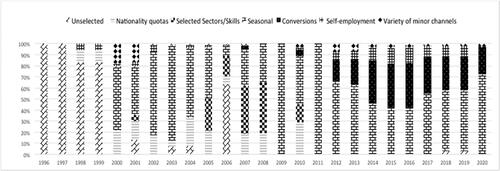

Between 2008 and 2009, the quota total dropped from 230,000 to 80,000 slots and the latter were just for seasonal workers. In 2010, the quota was more generous (184,080 slots), due to a temporary improvement in economic conditions (Pastore, Citation2016). However, between 2011 and 2020, less than 60,000 places were available with around 30,000 available after 2015. Since 2009, most entries have been for seasonal migrants, people with stay permits in Italy who apply to convert them to work permits and applicants for self-employment permits.Footnote8 While this is not the first time that non-seasonal migration is curtailed in Italy, it is the length of time—a decade at least—which distinguishes this period from previous ones.

Two regularization programmes were carried out in 2009 and 2012, the first solely aimed at domestic and care workers (Bonizzoni, Citation2018). Italian governments then refrained from carrying out regularizations for eight years; the longest gap between regularizations since the first one in 1986. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the center-left populist government regularized migrants working in agriculture or domestic work, providing them with short six month permits (Human Rights Watch, Citation2020). Thus, over time, regularizations have become more selective and less generous with regards to permit length ().

Figure 2. Non-EU labour migrant quota composition 1996–2020.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on data from the Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociale, cross-checked with (Callia et al., Citation2012; Perna, Citation2019).

These changes constitute first order changes, where the settings of the instruments were adapted. However, their effects on opportunities to migrate to Italy/seek regularization have been arguably larger than the more significant regulatory change made by DPR No. 189/2002, i.e., eliminating the job seeker permit. This suggests that it may be necessary to distinguish between the magnitude of institutional change and the effects of those changes as sometimes alterations in settings have larger effects than institutional displacement.

Accounting for change

The Italian economy was in the throes of crisis between the Great Recession of 2008 and 2020, apart from a brief reprieve between the end of 2009 and mid 2011 (Einaudi, Citation2018). Indeed, between 2008–2017, Italian GDP grew less or declined more than average EU levels (Colombo & Dalla-Zuanna, Citation2019). This economic crisis reduced low skilled labor demand and led to a rise in migrant unemployment, higher than that among natives (while the overall unemployment rate reached 12% in 2013, the rate was 17.9% for foreigners), making a restrictive approach to immigration economically and politically expedient (Interview 1, 2)(Einaudi, Citation2018). As a technical advisor to the GDIIP of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs asserted “The change in approach since 2008 is that no more labour migrants should come apart from seasonal migrants in agriculture, because unemployment is too high” (Interview 2). Furthermore, the refugee crisis made the issuing of generous quota decrees unlikely and dominated discussions of immigration (Interviews 3, 5).

These restrictive quotas were published under center-right, technical, center-left, populist, and populist center-left coalition governments; consequently, the explanation for the consistently small quotas does not lie in the political orientation of governments. The first restrictive quota decree was published during a center right government, with a Northern League Minister for the Interior Roberto Maroni (Massetti, Citation2015). However, this government oversaw the return to a normal quota in 2010 and it was a technical government which reduced the quota down to 60,000 in 2011.

Nonetheless, a concern with electoral outcomes in the context of the rising salience of immigration since 2011, and the growth in popularity of the Northern League from 2014, undoubtedly made all parties circumspect about emitting generous quota decrees (Interviews 2, 3). Indeed, while Italians have become less concerned regarding immigration over the past decade, they remain mainly negative regarding non-EU immigration and the Democratic Party position on immigration became less positive after 2010 (Dennison & Geddes, Citation2021).

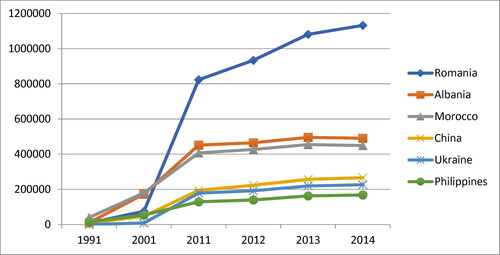

The economic and humanitarian crises were not the only drivers of the highly restrictive approach to labor migration since 2011, however. Another exogenous factor—developments within the Italian migratory system—while evolutionary in themselves—were part of the rationale for the rather dramatic restrictions imposed on non-EU labor immigration. This is an example of a dramatic change in goal partly based on an evolutionary exogenous factor. Senior officials of the Ministry of Labor and Social Policies and the Presidency of the Council of Ministers maintained in 2011 and 2021 that, based on an analysis of labor demand and supply, there was less need for non-EU labor migrants than before. As a senior official maintained in July 2011, “We will no longer need great numbers: family reunifications, intra-EU mobility and second generations will naturally compensate the labour mismatch that is currently tackled through labour migration from third countries” (Salis, Citation2012, pp. 34), while another asserted in April 2021, “It was obvious in a way. Even before Romania joined the EU, 25% of applications were from Romania… They have a language advantage as Romanian is close to Italian. It made sense to rely on internal EU migration, that’s what the UK did also…” (Interview 1). Indeed, Romanian migration to Italy started to grow spectacularly in the decade before its accession to the EU (Finotelli, Citation2009) and very limited restrictions were imposed on Romanian access to the labor market between 2007 and 2012. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Romanians were the first foreign community in Italy (Salis, Citation2012). Furthermore, family migration also became more substantial in the 21st century, representing the most significant inflow since 2011 (Geddes & Pettrachin, Citation2020; Salis, Citation2012). Finally, in the context of the European refugee crisis, asylum seekers have represented another functional alternative to labor immigration. In 2007, more than half of new residence permits were issued for working reasons, compared to 32.3% for family reunification and 4.3% for humanitarian/asylum protection. By 2017, however, residence permits for working reasons represented only 4.6% of new permits issued, while family reunification represented 43.2% and humanitarian/asylum protection 38.4% of new permits (Perna, Citation2019)(Interview 7).

While employer pressure for larger quotas declined during the second decade of the 21st century (Caponio & Cappiali, Citation2018), requests for quota slots have been higher than the number of available slots.Footnote9 However, these applications are not always viewed by policymakers as a reliable source of information on labor market needs, as the veracity of some of the employment offers is questioned (Interview 1). Indeed, in the second decade of the 21st century, quotas were set on the assumption that employers could and should access labor from within the country and there should be less need for further labor ‘inflows’. Indeed, the Immigration Decree Law No. 130/2020 (known as the “Lamorgese Decree”) provided for the conversion of (humanitarian) special protection permits, along with some other residence permits, into work permits ().

Conclusion

In this paper, I apply insights from institutionalism to the Italian labor immigration regime, with a particular focus on accounting for (1) the reproduction and overall inertia of the regulatory basis of the regime between 1990 and 2020 and (2) changes to instrument settings since 2008, in particular the significant restrictions imposed on labor immigration. Exploring a regime over a long period uncovers longstanding and recurring explanatory factors and allows for a more analytical approach to continuity and change. I have found that our understanding of labor immigration regimes is enhanced by the application of an institutionalist perspective, while the empirical findings of this case study also have theoretical implications for institutional research.

First, the immigration policy literature has tended to focus on change, rather than continuity, however, institutions, once established are often characterized by path dependence. The Italian regime—in particular, the quota system with the requirement of recruitment from abroad on the basis of a job offer—remained substantially unchanged between 1990 and 2020, despite some institutional layering, displacement and some first order changes (Hall, Citation1993). I applied the institutionalist legitimation, functionalist and power explanations to the case study. I find that the regime was reproduced in the 1990s partly because of a logic of appropriateness and remained in place since the 1990s due to the political weakness of opposition to the status quo and functional institutional complementarity. With regards to the latter, and with particular resonance for theories of gradual institutional change (Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2009), I find that informal rule breaking can bolster institutions rather than lead to their erosion.

Second, in investigations of immigration policy change, the magnitude of change is generally not sufficiently specified. Applying Hall’s taxonomy of policy change (1993), I find that changes were made to the settings and goals of the regime after the Great Recession of 2008. In particular, the overall size of the quotas was reduced and the number of non-seasonal slots has declined. While these recent changes are first order changes, their effects on labor immigration—in particular possibilities for legal entry and ex-post regularization—have been arguably more dramatic than the changes introduced in the late 1990s, early 2000s. Moreover, diverging from Hall’s taxonomy, changes to settings and goals can occur without changes in the instruments themselves. The former suggests that, in analyses of institutional change, it may be necessary to distinguish between the magnitude of institutional change and the effects of those changes as sometimes minor regulatory changes have larger effects than more major changes. This would involve a clear distinction between the level of regulatory change, the degree of implementation and its effect.

Third, again with implications for research on both immigration policy and institutional change, accounts of shifts to more restrictive labor immigration regimes have rarely highlighted the impact of gradual exogenous change, which has, on the other hand, been recently identified in institutional research. In particular, increases in the inward migration of non-labor migrants (e.g., free-movers and family migrants) can contribute to decisions to restrict labor immigration. However, while a recent typology of institutional change categorized gradual, exogenous sources of change as bringing about gradual institutional change (Gerschewski, Citation2021), this case study uncovered a dramatic change in settings and goal partly based on an evolutionary exogenous factor.

Notes

1 This paper focuses on entry criteria but notes some changes regarding permit renewal.

2 Even in 2011, 33% of permanent migrant inflows were work-related in Italy, the highest proportion of inflows in the OECD after Spain, Canada and the UK (Boucher, A., & Gest, J. (Citation2018). Crossroads. Comparative Immigration Regimes in a World of Demographic Change. Cambridge University Press.)

3 The Schengen area is a common travel area comprising European countries which have abolished passport control and other border controls at their mutual borders.

4 Decree of the President of the Republic.

5 The Foschi law of 1986 permitted employers to request foreign workers after passing a resident labour market test, which established that there were no Italians available for the job. Einaudi, L. (Citation2007). Le Politiche dell’immigrazione in Italia dall’Unità a oggi. Gius. Laterza & Figli

6 The rule of recruitment from abroad on the basis of a job offer is based on Labour Ministry circular no. 51, 1963. Bontempelli, S. (Citation2009). Il governo dell’immigrazione in Italia : il caso dei decreti flussi In P. Consorti (Ed.), Tutela dei diritti dei migranti : testi per il corso di perfezionamento universitario (pp. 115-136). Pisa University Press.

7 As government spokesman on immigration, Landi di Chiavenna, asserted in Parliament on 4th June 2002 ‘the precarious conditions of life in which the centre-left forced immigrants to live push them towards criminality, drugs, prostitution…’(Magnani Citation2012, pp. 656)

8 Furthermore, in the context of an accentuation of hostile discourse on immigration, the “security package” (Law 125/24 July 2008 and Law 94/15 July 2009) dramatically increased the cost of being issued a permit, among other provisions.Tuckett, A. (Citation2015). Strategies of navigation: migrants’ everyday encounters with Italian immigration bureaucracy. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 33(1), 113-128.

9 For example, 77.957 requests were made for 60,000 quotas slots in 2011, while 44, 649 requests were made for 30,850 places in 2016. De Ponte, F. (Citation2017). Decreto Flussi, ecco I dati del flop. Permesso solo a un richiedente su tre. La Stampa. , Veneto Lavoro. (Citation2015). Decreti Flussi Stagionali e Esiti Occupazionali: Il Caso di Padova Veneto Lavoro.

References

- Afonso, A., & Devitt, C. (2016). Comparative political economy and international migration. Socio-Economic Review, 3(14), mww026–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mww026

- Ambrosetti, E., & Paparusso, A. (2014). Le politiche di immigrazione sono restrittive? Risultati per l’Italia, 1990–2012. In Oltre I Confini (pp. 11–27). Sapienza.

- Ambrosini, M., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2011). Irregular immigration control in Italy and Greece: Strong fencing and weak gate-keeping serving the labour market. European Journal of Migration and Law, 13(3), 251–273. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181611X587847

- Baldwin Edwards, M. (1998). Where free markets reign: Aliens in the twilight zone. South European Society & Politics, 3(3), 1–15.

- Bennett, A., & George, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. MIT Press.

- Bonetti, P., D’Onghia, M., Morozzo della Rocca, P., & Savino, M. (2022). Immigrazione e lavoro: quali regole? Modelli, problemi e tendenze. Editoriale Scientifica.

- Bonizzoni, P. (2018). Looking for the best and brightest? Deservingness regimes in Italian labour migration management. International Migration, 56(4), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12447

- Bontempelli, S. (2009). Il governo dell’immigrazione in Italia: Il caso dei decreti flussi. In P. Consorti (Ed.), Tutela dei diritti dei migranti : testi per il corso di perfezionamento universitario (pp. 115–136). Pisa University Press.

- Boucher, A., & Gest, J. (2018). Crossroads. Comparative immigration regimes in a world of demographic change. Cambirdge University Press.

- Callia, R., Giuliani, M., Pasztor, Z., Pittau, F., & Ricci, A. (2012). Practical responses to irregular migration: the Italian case. Rome: IDOS Centre of Study and Research.

- Camera dei Deputati. (2002). Seduta n. 143 del 13 maggio 2002. Camera dei Deputati.

- Campbell, J. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton University Press.

- Campbell, J. (2009). Institutional reproduction and change. In G. Morgan, J. L. Campbell, C. Crouch, P. Hull Kristensen, O. K. Pedersen, & W. Richard (Eds.), The oxford handbook of comparative institutional analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Caponio, T., & Cappiali, T. M. (2018). Italian migration policies in times of crisis: The policy gap reconsidered. South European Society and Politics, 23(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1435351

- Colombo, A. D., & Dalla-Zuanna, G. (2019). Immigration Italian style, 1977–2018. Population and Development Review, 45(3), 585–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12275

- Cvajner, M., Echeverría, G., & Sciortino, G. (2018). What do we talk when we talk about migration regimes? The diverse theoretical roots of an increasingly popular concept. In A. Pott, C. Rass, & F. Wolff (Eds.), Was ist ein Migrationsregime? What is a migration regime? (pp. 65–80). Springer VS.

- Czaika, M., & de Haas, H. (2011). The effectiveness of immigration policies: A conceptual review of empirical evidence. IMI Working Papers, 33, 1–26.

- de Haas, H., Natter, K., & Vezzoli, S. (2018). Growing restrictiveness or changing selection? The nature and evolution of migration policies. International Migration Review, 52(2), 324–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318781584

- De Ponte, F. (2017). Decreto Flussi, ecco I dati del flop. Permesso solo a un richiedente su tre. La Stampa.

- Dennison, J., & Geddes, A. (2021). The centre no longer holds: The Lega, Matteo Salvini and the remaking of Italian immigration politics. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901

- Devitt, C. (2018). Shaping labour migration to Italy: The role of labour market institutions. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 23(3), 274–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2018.1459408

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Ebbinghaus, B. (2005). Can path dependence explain institutional change? Two approaches applied to welfare state reform. MPIfG Discussion Paper, No 05/2.

- Einaudi, L. (2007). Le Politiche dell’immigrazione in Italia dall’Unità a oggi. Gius. Laterza & Figli.

- Einaudi, L. (2018). Quindici anni di politiche dell’immigrazione per lavoro in Italia e in Europa (prima e dopo la crisi). In M. Carmagnani & F. Pastore (Eds.), Migrazioni e integrazione in Italia, tra continuità e cambiamento (pp. 197–231). Fondazione Luigi Einaudi.

- Finotelli, C. (2009). The north–south myth revised: A comparison of the Italian and German migration regimes. West European Politics, 32(5), 886–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903064747

- Finotelli, C., & Echeverrıa, G. (2017). So close but yet so far? Labour migration governance in Italy and Spain. International Migration, 55, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12362

- Finotelli, C., & Sciortino, G. (2009). The importance of being southern: The making of policies of immigration control in Italy. European Journal of Migration and Law, 11(2), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1163/157181609X439998

- Geddes, A. (2008). Il rombo dei cannoni? Immigration and the centre-right in Italy. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701847416

- Geddes, A., & Pettrachin, A. (2020). Italian migration policy and politics. Exacerbating Paradoxes Contemporary Italian Politics, 12(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2020.1744918

- Gerschewski, J. (2021). Explanations of institutional change: Reflecting on a “missing diagonal”. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000751

- Guiraudon, V. (2018). The 2015 refugee crisis was not a turning point: Explaining policy inertia in EU border control. European Political Science, 17(1), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0123-x

- Hadj Abdou, L., Bale, T., & Geddes, A. P. (2022). Centre-right parties and immigration in an era of politicisation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901

- Hadj Abdou, L., & Pettrachin, A. (2022). Exploring the EU’s status quo tendency in the migration policy field: A network-centred perspective. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2072937

- Hall, P. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

- Hall, P., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: Institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Heclo, H. (1974). Modern social politics in Britain and Sweden. Yale University Press.

- Helbling, M., Bjerre, L., Römer, F., & Zobel, M. (2017). Measuring immigration policies: The IMPIC database. European Political Science, 16(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2016.4

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). Italy: Flawed migrant regularization program. HRW. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/18/italy-flawed-migrant-regularization-program

- Lahav, G., & Guiraudon, V. (2006). Actors and venues in immigration control: Closing the gap between political demands and policy outcomes. West European Politics, 29(2), 201–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500512551

- Lutz, P. (2019). Variation in policy success: Radical right populism and migration policy. West European Politics, 42(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509

- Magnani, N. (2012). Immigration control in Italian political elite debates: Changing policy frames in Italy, 1980s–2000s. Ethnicities, 12(5), 643–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796811432693

- Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2009). Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and power. Cambridge University Press.

- Massetti, E. (2015). Mainstream parties and the politics of immigration in Italy: A structural advantage for the right or a missed opportunity for the left? Acta Politica, 50(4), 486–505. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.29

- McMahon, S. (2018). The politics of immigration during an economic crisis: Analysing political debate on immigration in Southern Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(14), 2415–2434. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1346042

- Natter, K., Czaika, M., & de Haas, H. (2020). Political party ideology and immigration policy reform: An empirical enquiry. Political Research Exchange, 2(1), 1735255. https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1735255

- OECD. (2008). International migration outlook.

- OECD. (2009a). Economic survey of Italy 2009: Supporting regulatory reform.

- OECD. (2009b). Workers crossing borders: A road-map for managing labour migration.

- OECD. (2015). Indicators of immigrant integration.

- Olsen, J. P., & March, J. G. (2004). The logic of appropriateness. ARENA, No. 9

- Pannia, P. (2021). Tightening asylum and migration law and narrowing the access to European countries: A comparative discussion. In V. Federico & S. Baglioni (Eds.), Migrants, refugees and asylum seekers’ integration in European labour markets. Springer.

- Pastore, F. (2016). Zombie policy politiche migratorie inefficienti tra inerzia politica e illegalità. Il Mulino, 4, 593–600.

- Perna, R. (2019). Legal migration for work and training: Mobility options to Europe for those not in need of protection Italy case study.

- Piro, V. (2020). Politiche migratorie e disfunzioni funzionali: il caso della legge Martelli. Meridiana: Rivista di Storia e Scienze Sociali, 97(1), 245–260.

- Salis, E. (2012). Labour migration governance in contemporary Europe: The case of Italy.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2017). Theorizing ideas and discourse in political science: intersubjectivity, neo-institutionalisms, and the power of ideas. Critical Review, 29(2), 248–263.

- Sciortino, G. (2009). Fortunes and miseries of Italian labour migration policy.

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. A. (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.

- Sydow, J., & Koch, J. (2009). Organisational path dependence: Opening the black box. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 689–709.

- Tondelli, J. (2018). Immigrazione, populismi, quel che resta di Craxi: Intervista a Claudio Martelli. Il Sale Sulla Coda: Quattro incontri di Politica conditi con una dose di sincerità. Milan Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli

- Tuckett, A. (2015). Strategies of navigation: Migrants’ everyday encounters with Italian immigration bureaucracy. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 33(1), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.3167/ca.2015.330109

- Veneto Lavoro. (2015). Decreti flussi stagionali e esiti occupazionali: Il caso di padova. Veneto Lavoro.

- Wright, C. (2014). How do states implement liberal immigration policies? Control signals and skilled immigration reform in Australia. Governance, 27(3), 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12043

- Zincone, G. (2006). The making of policies: Immigration and immigrants in Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32(3), 347–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830600554775