Abstract

This article presents findings from research on women’s lived experiences with technology in refugee resettlement. Participants include focus group discussions with 22 refugee women and interviews with 26 staff from refugee serving organizations in Washington state. We adopt a feminist socio-technical approach and draw on feminist and transformative methodologies. The research engaged participants in discussions about technology including ICTs, household appliances, transportation technology, and financial services such as ATMs. From our findings, we consider how women learn technology and learn to navigate three socio-technical ecosystems in everyday life: (1) the resettlement process (2) public daily life, and (3) home and community.

Introduction

In this research, we explore the relationship between access to technology, technology education, and social and economic inclusion for refugee women in the United States. The results contribute to a deeper understanding of the social and technological environments where refugee women live, how women learn to use tools and technology systems, and women’s access to technology education programs through refugee serving organizations. We theoretically situate our work within feminist science and technology studies (feminist STS) and draw on qualitative research with staff from refugee serving organizations and with refugee women in Washington state.Footnote1

Research demonstrates the important role of the social aspects of refugee resettlement, and especially so for women (e.g., Berg, Citation2022; Correa-Velez et al., Citation2020; Iqbal et al., Citation2021; Shaw & Wachter, Citation2022). Due to the increased intersection of social and technological elements of daily life, digital technologies such as social media and mobile phones become “lifelines” by providing social bonds and bridges for refugees (Berg, Citation2022; Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2021; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2016). At the same time, financial, linguistic, cultural, and employment barriers limit many refugee communities’ access to technology and to technology education (Dahya et al., Citation2020). Our work responds to a need to research and understand the role of technology for refugee women in resettlement (Berg, Citation2022; Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2021). Technology has historically disadvantaged women and constructed exclusionary environments that deter and limit women’s learning, engagement, and development of technological tools and systems (Wajcman, Citation2010). Technology education and access programs do exist for refugees and other groups of migrant men and women through government, non-government, and public services (Dahya et al., Citation2020). These programs largely focus on information and communication technologies (ICT) such as computers, email, and internet use. However, the impact and uptake of these programs for refugee women is unclear, and inquiry using household appliances and public technologies like ATMs and self-checkouts, etc., is sparse.

In this research, we spoke with women about different types of technology used in their daily lives. While we include digital tools such as mobile phones, we distinctly also focus on technology such as driving cars, using maps, and using household appliances. In this paper, we: (1) provide insight into women’s lived experiences navigating different social and technical environments; (2) frame these findings within the theoretical lens of feminist STS; and (3) discuss the implications of these findings for learning technology through everyday practice and technology education programs. We present our findings through an analytic framework we call “socio-technical ecosystems,” overlapping constructs where resettlement and technology intersect.

Research rationale & background

Research questions

Our focus on technology access and education stems from the importance of learning to use technology and having opportunities to practice and engage with technology as part of everyday life in the United States. The research questions guiding our study are:

What is the socio-technical landscape refugee women navigate during their resettlement in the United States?

How do women interact with and learn to use technology in their daily lives?

What types of social and technical opportunities and challenges surface for refugee women in relation to technology access and education?

The following sections offer an overview of the existing literature about the role of ICT to support refugee resettlement and introduces feminist socio-technical theory. Using a feminist socio-technical approach further engenders migration and refugee studies scholarship and leads to better understanding the lived reality of the women represented in this study.

Refugee status in the United States

The term “refugee” carries systemic, legal, and structural implications for the women who are designated as such, in addition to their varied social, cultural, and political backgrounds (Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2018; Zetter, Citation2015). “Refugee” is a legal term defined as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” (UNHCR, Citation2010). In the United States, someone’s legal status as a refugee or another type of migrant determines what kind of government services they can receive on arrival. In particular, during the first 90 days of refugees’ resettlement, funding goes to resettlement agencies to help refugees apply for financial assistance, enroll in programs to learn English, and prepare for the job market.

Following this early arrival period in the United States, refugees have access to a range of programs through Refugee Serving Organizations (RSOs), including Community-Based Organizations (CBOs), and services such as public library programs. Participants typically vary in age, arrival time, and ethno-racial background, among other markers of identity. Our study captures a rich picture of this very dynamic and multifaceted world in the lived reality of women.

Literature review: ICTs in refugee resettlement

Digital technologies play a key role for refugees in the resettlement process. Newly arrived refugees use technology for social, emotional, and informational support (Mikal & Woodfield, Citation2015). Many refugees today use smartphone technology to communicate with friends and family abroad, or to cultivate relationships with those in their host country through social media applications such as Facebook, WhatsApp, or Skype (Veronis et al., Citation2018; Bletscher, Citation2020; Guberek et al., Citation2018; Shah et al., Citation2019). Digital technologies are key to social connections (Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2021), and to searching for information related to employment, education, transportation, banking, domestic or international news, language translation, and social service agencies (Bletscher, Citation2020; Mikal & Woodfield, Citation2015; Sabie & Ahmed, Citation2019; Veronis et al., Citation2018).

However, the high cost of devices and monthly service fees limit access to digital technologies. Recent research examines the financial barriers to digital access as the price of connectivity limits the possibilities for refugee women to engage in the digitally mediated work and hinders their economic inclusion (i.e. Alencar & Camargo, Citation2023; Easton-Calabria, Citation2019). Without personal access, many refugees use public computers at libraries, community centers, or local NGOs to conduct job searches and complete job applications (Bletscher, Citation2020; Simko et al., Citation2018). Barriers to internet access increase time obligations and require refugees to complete more tasks in person (Mikal & Woodfield, Citation2015, p. 1328). Unfamiliarity with complex technical systems leaves refugees more vulnerable to digital security risks such as identity theft, financial loss, and computer viruses (Bletscher, Citation2020; Sabie & Ahmed, Citation2019; Simko et al., Citation2018). For refugees with limited English language fluency, language barriers compound technical challenges.

For these reasons, focusing on technology access and education provides critical insight to refugee women and communities’ lived experiences of resettlement and opportunities for social inclusion. RSOs, families, and friends all play important roles in supporting technology education and use for newcomers (Dahya et al., Citation2020; Sabie & Ahmed, Citation2019; Simko et al., Citation2018). Organizations teach either in formal classes or on an ad hoc basis via case managers, sponsors, language teachers, or volunteers. ICT dominate the programming available, such as logging into email and applying for jobs. Refugees supplement their technology learning and assistance with friends, spouses, or children to learn digital tasks (Dahya et al., Citation2020; Sabie & Ahmed, Citation2019).

In this existing ICT landscape, we note a dearth in research related to non-ICT technology in women’s lives and how women learn to use these tools. Additionally, we only encountered a few examples that use a feminist socio-technical approach to study the interaction between refugees, technology, and learning and these are situated in refugee camp settings (e.g., Dahya et al., Citation2019; Dahya & Dryden-Peterson, Citation2017). In the English-speaking literature we reviewed, we did not find any research that uses a feminist STS approach to explore social inclusion for women in resettlement. Taking a feminist perspective surfaces questions about how and which technologies are used by women, women’s agency and education opportunities, barriers to technology access, and the range of support (or lack thereof) available to women to navigate different tools and systems.

Theoretical framework: a feminist approach to the study of refugee women and technology

Feminist STS has profoundly shifted our conception of technology both as an artifact and as a set of cultural and social practices embedded within tools and systems (Bijker et al., Citation1987; Wagman & Parks, Citation2021; Wajcman, Citation2010). A mutually constituted relationship between technology and society creates and re-creates gender and gender power dynamics in the process of technology development and use (Wyatt, Citation2008). Power and control are exerted between people related to their technology literacy, and technological knowhow is unevenly distributed by age, gender, and English language levels, among other factors. Masculine conceptions of technology related to ideas of work and war dominate the social world of technology, and in turn, overlook other technologies of everyday life (Wajcman, Citation2010). For example, taking “technology” to mean weaponry or computing reaffirms the association between tools of these industries, male-centric culture, and men’s power over these dominions. However, as Wajcman (Citation2004) explains, “A revaluing of cooking, childcare, and communication technologies immediately disrupts the cultural stereotype of women as technically incompetent or invisible in technical spheres” (p. 144).

The uses and appropriations of technology depend on social contexts and respond to the needs, aspirations, and lived experiences of people at a given point in time. The interdependent relationship between society and technology is fluid; the ways gender-based power relationships influence education about technology—and its use and access—matter. These relationships impact participation in society and also in the construction of society. This theoretical premise is foundational for the study of refugee women and their entanglements with technology in resettlement, as they both seek social inclusion and contribute to the shape and form of society. Such an approach foregrounds women’s agency in the ways they consistently interpret, use, learn, and appropriate technology in their everyday lives and in the ways their interactions with technology inform society.

Feminist migration scholars demonstrate the social inequalities experienced by women and how they are constructed and reconstructed in migrants’ and refugees’ transnational social fields (Hyndman, Citation2010; Nawyn, Citation2010). As Nawyn (Citation2010) rightly states, “questioning the heteronormativity of migration policy, destabilizing masculinity and its privilege, and uncovering the political implications of how work itself are defined, [are] the different ways in which critical social theory has contributed to migration scholarship” (p. 759). Our contribution through this research is (1) to further understand the lived realities of refugee women and technology, (2) to disrupt cultural stereotypes and assumptions about refugee women and technology, and, (3) to consider the implications of these findings for women’s programs and support throughout their resettlement.

Methods

Feminist & transformative research design

For this study, we adopted a feminist and transformative research design (Bletscher, Citation2020; Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2010). This approach focuses on the lived experiences of women throughout the study (Harding, Citation1988; Lather, Citation1991), and “incorporat[es] intent to advocate for an improvement in human interests and society through addressing issues of power and social relationships” (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2010, p. 441). A feminist practice also involves positioning ourselves within the work. As a team, we are, collectively, university researchers and a mix of nonwhite and white women with different first languages and diverse experiences of migration to the United States and elsewhere in our lifetimes. Our individual backgrounds, experience with technology and migration, and relative positions of power and privilege as university researchers influence the approaches we take in our work.

Data collection and analysis

Data was collected in three consecutive phases: (1) desk research; (2) semi-structured interviews with organizations that serve refugees; and (3) focus group discussions and interviews with refugee women. First, the desk research involved searching for refugee serving organizations (RSO) in King County, Washington. This led to outreach with key informants from our RSO networks. In these informal discussions, we asked about the relevance of the research for RSOs and refugee women. These discussions allowed us to refine the research questions and identify and recruit organizations for the research activities. We then conducted interviews with 26 people working for 21 different RSOs in early 2019 ().

Table 1. Participating refugee serving organizations (RSOs).

Recruitment of refugee women happened through convenience sampling coordinated by the participating RSOs. In Spring 2019, 22 refugee women were offered one-time, monetary compensation to participate in focus group discussions. Recruitment targeted women who had arrived in the United States between 2009 and 2019. However, women who participated often arrived with friends, some of whom had arrived years before them. In cases where only one woman arrived, we conducted individual interviews. There were six focus group discussions (FGD) and three individual interviews (INT) conducted. Participants came from Russia, Ukraine, Vietnam, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Somalia, Kuwait, Ethiopia, and Burma. summarizes the country of origin, years living in the United States, and data collection method. Most women came directly to the United States from their homeland, and five lived in refugee camps before resettling in the United States.

Table 2. Refugee women participant information.

Most of the focus groups involved members of the same ethno-linguistic community, though one was a mixed group including women from Iraq and Somalia. Focus group discussions happened in English and included participants speaking in their first languages, including Vietnamese, Russian, and Amharic. In these cases, peer participants served as translators and all recordings were professionally transcribed and translated for analysis.

The interview and focus group data were anonymized and analyzed through a process of iterative and collaborative thematic coding. One codebook was created for the entire dataset, informed by existing literature, and built using emergent themes. We started to analyze RSO interviews first while data from refugee women underwent translation and transcription. Examples of codes included technology access and education, with sub-themes for learning, purpose of use, organization challenges, role of technology in women’s lives, and social/cultural inclusion, to name a few. The results from interviews with service providers were presented during a practitioner workshop on February 20, 2020. We drew on the feedback and generative activities of this workshop to inform a practitioner report published later that year (Dahya et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

Study participants were recruited through RSOs, meaning that the research team did not have direct contact with refugee women participants regarding meeting times, places, and schedule interruptions. We had initially requested that recruitment focus on women who had arrived as refugees within the preceding decade (2009–2019). Our recruitment through RSOs resulted in a wider range of arrival dates, with one arrival date as far back as the 1990s. This means participants’ refugee experiences varied greatly in terms of the political climate of their entry and in terms of the socio-technical landscape of their arrival. At the same time, this varied participant group represented the range of experiences among community members. It also illuminated some commonalities across countries of origin and arrival dates. Lastly, we were unable to consult with refugee women participants about our findings after the completion of data analysis due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Findings

Refugee women, learning, and socio-technical ecosystems

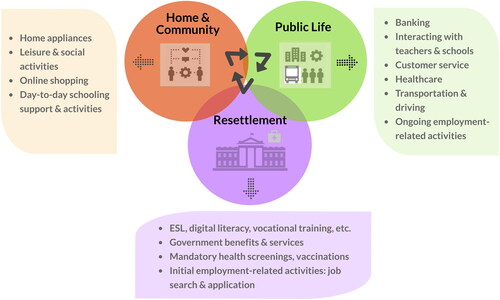

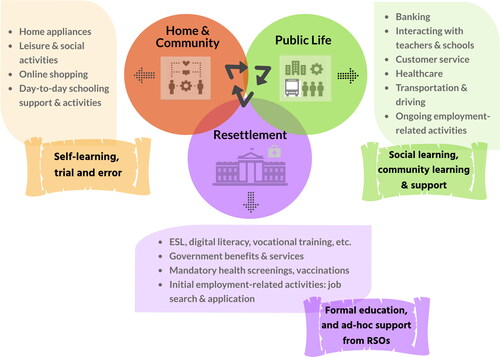

The insights offered across this study give a cross-sectional view into refugee women’s technological worlds. Women in this study talked about technology in their lives, past and present. RSO interviews informed us of technology services available, typical beneficiary groups, and their view of refugee women’s needs, challenges, and successes. We have synthesized the results of our analysis into three overlapping socio-technical ecosystems: (1) resettlement; (2) public life; and (3) home and community (). These ecosystems are relational, dynamic entities. We also identify key ways in which women learn how to use technology as they navigate these ecosystems: self-learning, learning with family and community members, and learning with organizations that serve refugee communities. Learning is addressed in more detail in the discussion section of the paper.

The resettlement ecosystem

The resettlement ecosystem encompasses interactions between technology and women’s lives related to resettlement procedures and programs: obtaining education certificates and credential records, accessing government support programs, applying for citizenship, and preparing for employment. The period of early arrival for refugees in the United States is structured around the economic push to find employment as soon as possible.Footnote2 During the brief early settlement period, building skills to support employment—including basic digital technology training—is the main priority of many organizations. These skills include job searches, applying for jobs, resume building, job interview practice, and professional communication. A refugee woman describes the difficulties adjusting to the new U.S. socio-technical landscape:

It’s stressful for us as well, all those passwords and stuff. Each of us has a phone book where we write down things like, "Paying for tickets: password is this, log-in is that." Next to it goes, "Internet: password is this, username is that." Then, we got those teacher certificates, and "the numbers that were assigned to us are as follows" and writing the number down. We have an entire notebook where we write everything down, our appointments, phone numbers, etc. Because we didn’t have such a system back where we’re from, whilst in the U.S. it’s commonplace.

Source: Participant 10, RW FGD(3)

We have programming such as LinkedIn trainings, digital literacy, Microsoft, a professional mentoring program, customer service, and financial literacy.

Source: RSO INT(9)

One participant describes the job search support she received from the resettlement agency:

The [resettlement agency] keep[s] us always in touch. They send us emails. They tell us, "There is this event, there is this job fair, there is this. … You can come."

Source: Participant 22, RW INT(3)

I did learn the computer for two months…Then I stopped because I had to go to school for learn how to do the nail…

Source: Participant 7, RW FGD(2)

So one program that we’ve funded a few times over the years…[has] been working, not with just Burmese folks, but they have had a program to teach ESL to parents of students in [Seattle]…and there was such a huge need for digital literacy in addition to basic ESL…When people are learning English, it’s really helpful to learn technology at the same time…So that’s a program…the parents would come in, their kids would go to school, and they would gain basic digital literacy but also engagement opportunities with the schools, so understanding how to navigate The Source [student portal] and email and communicate with teachers…

Source: RSO INT(20)

All four of us are studying in college. The three of us go to ESL classes. We communicate there, we constantly meet new people there…I just didn’t have a chance to meet her except for the class. We continue to stay in touch, keep connected, and ask about each other.

Source: Participant 10, RW FGD(3)

For refugees with professional backgrounds, the challenges of entering a new socio-technical system are also nuanced.

A doctor here, you finish in medical school in this country…If you take him [to] … my village to work as a doctor, the results will be poor comparative to here, because you take away technology from him, he’s done… In the same way, a doctor from [my home], they bring him here, they put him in [a U.S. hospital]. You put technology in front of him, he’s done.

Source: RSO INT(14)

Each doctor has been trained to succeed in their particular socio-technical environment. As refugee communities enter complex, new socio-technical ecosystems, they learn how to navigate the different paths, procedures, and professional and legal expectations. Classes that support longer-term employment outcomes for populations from refugee backgrounds with professional training—architects, engineers, doctors, etc.—integrate more advanced technology training, including Microsoft Office certifications, different online courses and tutorials, and professional certifications that enable them to transition into their fields of expertise. Technology has to be learned and understood in context, and service providers do support these learnings, especially related to the use of computers and phones in employment settings.

The ecosystem of public daily life

The second ecosystem, public daily life, focuses on interactions with society and includes: (1) digital technologies needed to engage with schools, banking, transportation, and commerce; and (2) other public technologies such as using self-checkout at grocery stores, using parking meters, and driving cars. One participant described a first encounter at a grocery store:

I remember that at [grocery store] they have self-checkout machines. I was really curious. Nobody showed me how to use those. So, I stood there like this, watched what people were doing. Now, I have to do the same thing, going to figure out how. I try and think, "If It’s not going to work – somebody will come to me."

Source: Participant 11, RW FGD(3)

USA is really developed in technology, so the thing is I’ve seen that here in America, when you’re using buses, there is a place where you can put money, it goes, they give you a ticket. There’s a place where you tap your card, then you go and have your seat, but in Africa, you just give [money]… There is a driver and [that’s it]…

Source: Participant 17, RW FGD(5)

Many RSO interviewees also described navigational tools as important technologies for women in resettlement. RSOs taught women about maps and public transportation mostly in ad hoc ways, primarily in one-on-one settings. One organization did introduce women and men to public transportation by arranging a half-day field trip. The trip included a pre-planned itinerary based on the needs and interests of the group; printed and translated Google Maps with step-by-step directions and pictures; and preloaded electronic bus cards.

In some of our interviews, women mentioned that their husbands had arrived in the United States first and had more familiarity with English and technology. One participant explained:

I have [a] problem with driving…Then I call my husband, "Can you pick me up?" [laughs] Then he told me [I] need to learn how to use the Google Maps, but sometimes I focus when driving, and I cannot listen the same time because my English not very good…

Source: Participant 5, RW FGD(2)

Another common theme that emerged is engaging with education systems. RSO interviewees described classes that teach women to interact with educational systems such as K-12 public schools. These training sessions include learning how to use school apps to monitor children’s grades; learning how to communicate with teachers and administrators; and learning about institutional policies and structures. One RSO interviewee explained:

Seattle Public Schools moved to kindergarten registration only happening online, which seems insane. [laughter] So they had a lot of community meetings to help people transition. But it’s like, "You’ve got a lot of work to get people to the point where they can feel comfortable doing that." And it’s like, this is kindergarten. [Not] much less high school and college, where it gets really complex. And all of those things are tied into your self-esteem and how [do] you feel—like you are part of this country and you belong in this world. If you don’t have those, that has a big impact.

Source: RSO INT(7)

In addition, women seek support for their own higher education enrollment and activities. One participant described enrolling in college and applying for financial aid. The woman went through the online application system and then needed her parents to sign the form electronically and include their government identification information, which proved to be a challenge. The following excerpt describes the situation as it unfolded.

So I went to [college], I registered myself, and they accepted me, and I applied for financial aid. … [My parents] completed everything. They completed their addresses, names, email address. … Social Security, everything, only [needed to add] the signature, I [clicked] on signature, it’s not coming out. So they told me [what to do], to go and scan, make a signature, and send it through [the] mail.

Source: Participant 17, RW FGD(5)

As the participant worked through this process, the deadline for submission passed and she did not know how to proceed or if she could still apply, given the various technical and logistical difficulties she had in navigating the system. Another participant explained:

I also wanted to tell you about the college computer system, which works in a very interesting way. It’s really hard to figure out all those passwords and stuff. When I came there for the first time, I was like, "How do I type it all?" You just stand there, trying to figure out what to do. You’re trying to enter the password; done, you gain access. After that, you need to use the printer in the black-and-white mode then use the color mode. They also had these posters hanging there with instructions, like the ones they saw in the public restroom. I also had to figure out what to do, what they show. You think you know how to work with computers, but there are still some quirks you have to learn.

Source: Participant 10, RW FGD(3)

The ecosystem of home & community

The women who participated in this study expressed the ways in which home life, family care, and community engagements dominated their everyday experiences with technology. Much of the discussion in this ecosystem focused on domestic appliances. There was some variation in terms of broad technology literacy, such as comfort and prior exposure to domestic tools such as laundry machines. One participant said:

At first, I didn’t understand how to use the dryer at all. [My friend] came to me and says, “What kind of a greasy layer do you have here?” I say, “How do I know? This is the first time in my life I saw a dryer. How do I know that it has to be cleaned?"

Source: Participant 11, RW FGD(3)

Participant 5: Mom, is there anything in the kitchen that you don’t know how to use?

Participant 6: I think the oven, when I cook the cake.

Interviewer: Bake it?

Participant 6: Yes. I didn’t know how to change to medium, low, or high. …Then I learn on computer. I learn it, and I do again. [laughter]

Source: RW FGD(2)

Another explained,

We cook, sometimes we can try with the new food like American food, something like that, we learn. Some Vietnamese food we can learn too. Whatever we like, we don’t know, we learn from them. … I’m watching the YouTube tips, how to cook, how to do art on the nails, something like that.”

Source: Participant 5, RW FGD(2)

Women turned to YouTube and social media to learn how to use household appliances, build skills related to household work and crafts, learn new hobbies, improve employment skills, join communities, prepare for the citizenship test, and watch news from their home country. Women also use Netflix and other television streaming and cable to learn English. One participant talked about her mother’s learning and use of mobile phones and social media:

[Mom] is not very good at technology. But she also [has] a smartphone. She says, "Because everybody has it, so I have to have it." And now she’s learning, actually, she’s learning. Now she knows how to use YouTube, how to use WhatsApp. And the rest, no. That’s it. She says, "That’s enough for me."

Source: Participant 22, RW INT(8)

Women’s competencies with technology varied greatly, and yet, commonalities related to situated literacy in the context of resettlement were evident. In another example, a participant explained:

We use the trial-and-error approach to learn things. For example … we edit a video in Pinnacle Studio or Photoshop. We just click on stuff and see what it will do. Sometimes you watch those lessons or guides on the internet but there aren’t that many of them, especially hard to find ones in Russian. In English, yes; in Russian, no. The same goes for everyday life. You go ask somebody who’s been here longer than you, or you ask your relatives who aren’t that enthusiastic, to teach you how to use this thing or that. So, it’s the same trial-and-error approach for everyday life too.

Source: Participant 13, RW FGD(3)

Discussion

Women living and learning with technology in resettlement

Women learn to navigate different socio-technical ecosystems as part of their daily lives and activities. In this research, we have drawn on the voices and perspectives of refugee women and RSOs to frame the three socio-technical ecosystems presented. Distinctly, we demonstrate the interrelated and overlapping nature of social and technological engagements refugee women face. In this discussion, we address how women learn to navigate these socio-technical ecosystems and contribute a crucial dimension to feminist STS and to refugee studies.

In our analysis, we incorporate gender power relations and situate them in a particular socio-cultural and political milieu. For example, refugee women in this study take on the majority of domestic labor and their technological literacy needs are largely overlooked in this domain. Approaching the role of technology in the lives of refugees from a gender-based perspective illuminates realities specific to what can be described as “‘women’s work.”’ Previous research has identified the importance of ICT in the lives of refugees (e.g. Mikal & Woodfield, Citation2015; Sabie & Ahmed, Citation2019; Simko et al., Citation2018). Our work adds insight to the specific challenges, opportunities, and dynamics identified by refugee women about their daily lives and in relation to how they learn to engage with technology in the everyday.

Within each of the three ecosystems presented throughout this paper, women had to learn to use new tools, adopt existing tools for new activities, and interact with necessary technology systems. Across these ecosystems, we identified three different types of learning under way: (1) self-learning (including trial and error and exploration); (2) drawing on family and community support as needed; and (3) participating in classes or learning from organizations’ staff and volunteers. presents the three socio-technical ecosystems and their primary learning styles.

In the ecosystem of resettlement, organizations that serve refugees support women’s interactions with technology during formal programming. Women often spend time enrolled in mandatory or voluntary courses offered by RSOs or in courses at community colleges to further improve their English language skills and/or to obtain certifications in Home Care and Early Childhood Education. These programs often integrate technology learning, but it is not always the focus. Participants have to learn to use computers to engage with the curriculum, or RSO staff teach participants how to use their email or phones on the fly as their learning and literacy needs surface.

Within the ecosystem of public daily life, women’s perspectives on technology bring to the forefront the significant realities of social inclusion and anxiety. Mikal and Woodfield (Citation2015) note that internet usage is instrumental for both men and women to gather information, make purchases, and attend to children’s education; this is particularly true for newer arrivals that already used the internet as part of their lives. Our work confirms these findings and reveals a nuanced understanding of the challenges women face. The socially and politically constructed environment exerts pressure on women conducting these public-facing technological tasks, and thus examining these tasks outside of the lived contexts of women does not capture the full complexities of their experiences. As a related example, Alencar and Camargo (Citation2023) describe how for Venezuelan refugee women in Brazil lack of affordability of internet connection and devices forced them to navigate different public spaces in the city to find free wi-fi (i.e. bus stops, shopping malls, city halls) in order to engage in digital work. The need to create digital offices in public space adds a layer of stress and anxiety as women must balance issues of connectivity, safety, and the need to generate income and provide for their families. The anxieties of the public impact technology use for refugee women.

English language skills intersect all these interactions. Women learning English face additional stress when participating in technology mediated activities such as transportation and navigation, shopping, and schooling. Women use support from their family and community to and learn how to navigate these different socio-technical systems. However, this may be the ecosystem where women expressed the most anxiety and the least support. Interestingly, where Sabie and Ahmed (Citation2019) identify refugees in Canada using various apps in their most fluent language (e.g. Arabic), the women we interviewed described an inability to use apps and various other technologies due to English language barriers. Further research is needed to explore levels of technological literacy and traditional literacy among newcomers using technology in resettlement, and among women-identified newcomers in particular.

The ecosystem of home and community reveals the ways in which women enact their agency over new and existing tools to new ends, including domestic technology and media. Many participants and service providers described husbands and children as the mediators of technology for women, sometimes helping them navigate typing, search engines, and other elements that rely on a moderate level of English literacy. Some women said their husbands translate the news for them entirely. In other cases, patriarchal family dynamics limit their ability to manage their own digital technologies. One resettlement agency discussed the challenges of communicating with women when a husband or father acts as the point of contact for the family. In some cases, women may not answer their own calls or access voicemail. These examples demonstrate that the relationship between technology and the role of men to either support or control women’s lives is highly varied.

At the same time, women described learning to use tools through their own interests and among family and friends. Recognizing the role of technologies in women’s lives illuminates how and where their energies are spent day to day and, from a feminist STS perspective, reveals the way women’s work and labor with technology is omitted from public view. Women’s technological work in the home and use of both domestic tools and digital media for leisure and learning goes unrecognized, remaining hidden from view. This reality aids in the perpetuation of a masculine culture of technology by way of omission and invisibility (Wajcman, Citation2004) related to refugee women and technology interactions. Our work shows how women’s self-directed learning related to domestic technology, using social media and family or community connections, is noteworthy, providing insight into technology access and learning in this private domain.

When we look at the meeting point of the three socio-technical ecosystems described in this paper, we see opportunities for technology access and education. For example, much learning and community engagement happens at home and through peer-to-peer networks, and RSOs could collaborate with community members to create language and employment programs that build on the existing strengths of these communities. What types of social media and digital content available online can be turned into employment programs for at-home and peer-to-peer learning? How can programming support diminish stress and anxiety related to new domestic tools, or engaging in complex systems such as driving, navigation, or transportation? How can RSOs support newly arrived women seeking to learn to navigate these socio-technical ecosystems, rather than focus on learning specific tools? To help answer these questions, academics can explore what types of feminist, anti-racist, and community-led design practices can further inform knowledge of this landscape for those involved, namely refugee women themselves and supporting RSOs (i.e. Hedditch & Vyas, Citation2023; Kuneva & Hough, Citation2023; Nikolopoulou et al., Citation2022; Sarria-Sanz et al., Citation2023).

It is clear that understanding how to use technology systems in everyday life in the United States is important for women’s integration and socioeconomic mobility. Technology remains under-recognized in much of the research and practice under way to support refugee resettlement and social inclusion, particularly related to technology outside of computers, mobile phones, and social media.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that refugee women are engaged in various forms of technology learning, and it depicts the overlapping socio-technical ecosystems within which they live. In doing so, this work can inform pathways forward in program and policy development for service agencies working to support them. It can also inform how to look at the lives and technological investments women make every day to support their own social inclusion, and that of their families, in resettlement.

Through this research, we argue that to interrupt the male-dominated culture of technology, it is necessary to understand the ways in which women and other marginalized groups such as refugees learn and use technology. Showing the importance of domestic technologies such as ovens and laundry machines, as well as that of public technology systems including banking and transportation, broadens our collective conception of what “technology” entails, and then, what types of technology learning programs are worthy of funding and development to support refugees in resettlement. Without expanding our view of what types of technology matter to women, important forms of learning and living with technology go unnoticed, and women’s contributions, learning, teaching, ingenuity, and growth remain obscured from view.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Washington state is one of the country’s top ten regions for receiving refugees, making services and programs available to refugees relatively robust.

2 Other scholars have described country-specific temporal realities, such as in Lloyd et al. (Citation2013) study from Australia, which segmented three time periods: the start of the resettlement process, early arrival, and then the longer settlement process.

References

- Alencar, A., & Camargo, J. (2023). Spatial imaginaries of digital refugee livelihoods. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 4(3), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.7227/JHA.093

- Berg, M. (2022). Women refugees’ media usage: Overcoming information precarity in Germany. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 20(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2021.1907642

- Bletscher, C. G. (2020). Communication technology and social integration: Access and use of communication technologies among Floridian resettled refugees. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 21(2), 431–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00661-4

- Bijker, W. E., Hughes, T. P., & Pinch, T. (Eds.). (1987). The social construction of technological systems. The MIT Press.

- Correa-Velez, I., Green, A., Murray, K., Schweitzer, R. D., Vromans, L., Lenette, C., & Brough, M. (2020). Social context matters: Predictors of quality of life among recently arrived Refugee women-at-risk living in Australia. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 18(4), 498–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2020.1734893

- Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s ‘migration crisis’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2010). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Dahya, N., Garrido, M., Yefimova, K., & Wedlake, S. (2020). Technology access & education for refugee women in Seattle & King County. Technology & Social Change Group, University of Washington Information School.

- Dahya, N., & Dryden-Peterson, S. (2017). Tracing pathways to higher education for refugees: The role of virtual support networks and mobile phones for women in refugee camps. Comparative Education, 53(2), 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1259877

- Dahya, N., Dryden-Peterson, S., Douhaibi, D., & Arvisais, O. (2019). Social support networks, instant messaging, and gender equity in refugee education. Information, Communication & Society, 22(6), 774–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1575447

- Easton-Calabria, E. (2019). The migrant union: Digital livelihoods for people on the move. UNDP. https://www.undp.org/publications/digital-livelihoods-people-move

- Guberek, T., McDonald, A., Simioni, S., Mhaidli, A. H., Toyama, K., & Schaub, F. (2018). Keeping a low profile? Technology, risk and privacy among undocumented immigrants. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173688

- Harding, S. (Ed.). (1988). Feminism and methodology: Social science issues. Indiana University Press.

- Hedditch, S., & Vyas, D. (2023). Design justice in practice: Community-led design. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 7(GROUP), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3567554

- Hyndman, J. (2010). Introduction: The feminist politics of refugee migration. Gender, Place & Culture, 17(4), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.485835

- Iqbal, M., Omar, L., & Maghbouleh, N. (2021). The fragile obligation: Gratitude, Discontent, and Dissent with Syrian refugees in Canada. Mashriq & Mahjar Journal of Middle East and North African Migration Studies, 8(2), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.24847/v8i22021.257

- Kuneva, L., & Hough, K. L. (2023). Fostering inclusion for refugees and migrants and building trust in the digital public space. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-10-2022-0137

- Lather, P. (1991). Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern. Routledge.

- Lloyd, A., Kennan, M., Thompson, K., & Qayyum, A. (2013). Connecting with new information landscapes: Information literacy practices of refugees. Journal of Documentation, 69(1), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411311295351

- Merisalo, M., & Jauhiainen, J. S. (2021). ‘Asylum-related migrants’ social-media use, mobility decisions, and resilience. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 19(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2020.1781991

- Mikal, J. P., & Woodfield, B. (2015). Refugees, post-migration stress, and internet use: A qualitative analysis of intercultural adjustment and internet use among Iraqi and Sudanese refugees to the United States. Qualitative Health Research, 25(10), 1319–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315601089

- Nawyn, S. J. (2010). Gender and migration: Integrating feminist theory into migration studies. Sociology Compass, 4(9), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00318.x

- Nikolopoulou, K., Kehagia, O., & Gavrilut, L. (2022). Easy rights: Information technology could facilitate migrant access to human rights in a Greek refugee camp. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 8(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00233-0

- Sabie, D., & Ahmed, S. I. (2019). Moving into a technology land: Exploring the challenges for the refugees in Canada in accessing its computerized infrastructures. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computing & Sustainable Societies - COMPASS 19 (pp. 218–233). https://doi.org/10.1145/3314344.3332481

- Sarria-Sanz, C., Alencar, A., & Verhoeven, E. (2023). Using participatory video for co-production and collaborative research with refugees: Critical reflections from the Digital Place-makers program. Learning, Media and Technology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2023.2166528

- Shah, S. F. A., Hess, J. M., & Goodkind, J. R. (2019). Family separation and the impact of digital technology on the mental health of refugee families in the United States: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(9), e14171. https://doi.org/10.2196/14171

- Shaw, S. A., & Wachter, K. (2022). “Through social contact we’ll integrate:” Refugee perspectives on integration post-resettlement. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2021.2023719

- Simko, L., Lerner, A., Ibtasam, S., Roesner, F., & Kohno, T. (2018). Computer security and privacy for refugees in the United States. In 018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) (pp. 409–423). IEEE.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2010). Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2016). Connecting refugees: How internet and mobile connectivity can improve refugee well-being and transform humanitarian action. UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/operations/5770d43c4/connecting-refugees.html

- Veronis, L., Tabler, Z., & Ahmed, R. (2018). Syrian refugee youth use social media: Building transcultural spaces and connections for resettlement in Ottawa, Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 50(2), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1353/ces.2018.0016

- Wagman, K., & Parks, L. (2021). Beyond the command: Feminist STS research and critical issues for the design of social machines. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449175

- Wajcman, J. (2004). TechnoFeminism. Polity Press.

- Wajcman, J. (2010). Feminist theories of technology. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34(1), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/ben057

- Wyatt, S. (2008). Feminism, technology and the information society: Learning from the past, imagining the future. Information, Communication & Society, 11(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180701859065

- Zetter, R. (2015). Protection in crisis: Forced migration and protection in a global era. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TCM-Protection-Zetter.pdf