Abstract

Background

2,4 dinitrophenol (DNP) is a toxic industrial chemical that reduces body weight and body fat by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation but at the risk of severe dose-related toxicity. Increases in human DNP exposures have been reported in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia in recent years, but little information is available for other countries. This study was performed in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish international rates of systemic DNP-related exposures and deaths, as reported to poisons centres.

Methods

Poison Centres listed in the WHO Directory of Poison Centres were contacted by email. Data were requested on numbers of enquiries relating to systemic DNP exposure by year, sex and clinical outcome (fatal/non-fatal) for the period January 2010 to September 2020.

Results

Responses were received from poisons centres in 38 countries which reported 456 separate cases of DNP exposure (303 male, 125 female, 28 sex not reported). Annual case numbers increased from 4 in 2010 to 71 in 2015, with subsequent reductions to 53 in 2019. On a population basis, case rates were higher in Australasia, Europe and North America than in Asia, Africa, and South or Central America, but with substantial differences in rates between countries within the same continent. When mortality data was available, case fatality was high (11.9%, 95% CI 9.0, 15.4) with no significant difference between females (11.3%, 95% CI 6.4, 18.9) and males (12.6%; 95% CI 9.1, 17.1; odds ratio 0.86, 95% 0.45, 1.73, p = 0.72).

Conclusions

Substantial increases in calls to poisons centres regarding human systemic exposures to DNP internationally between 2010 and 2015, especially those in Europe, Australia and North America, with fatal outcomes common. Countries affected should consider appropriate additional measures to further reduce the risk of human exposure to this hazardous chemical.

Introduction

2,4 Dinitrophenol (DNP) is an industrial chemical that reduces body weight and fat by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. It is, however, highly toxic, with small differences between doses that produce weight reduction and those leading to severe poisoning or death. Clinical features of toxicity include hyperpyrexia, tachycardia, acidosis and confusion and these can progress to death in spite of high-quality medical care [Citation1].

Fatalities associated with DNP exposure were first reported in munitions workers after industrial exposure during the First World War. During the 1930s, DNP was used medically for weight reduction in the United States of America (USA) until the Federal Food, Drugs and Cosmetic Act of 1938 declared DNP as dangerous and not fit for human consumption. Episodes of fatal DNP poisoning were subsequently rare until more recently [Citation2]. The National Poisons Information Service (NPIS), the network of poisons centres in the United Kingdom (UK), reported a sharp increase in reported cases and fatalities in 2012 and especially during 2013. [Citation3] A more recent collaboration between poisons centres in the UK and USA demonstrated increasing numbers of cases in both countries after 2012, with population-corrected rates substantially higher in the UK [Citation1]. Limited data are available about trends in DNP exposure in other countries, but the New South Wales Poisons Centre in Australia reported a sharp increase in cases in 2017 and 2018 [Citation4]. Cases of severe DNP poisoning have also been reported from several other countries [Citation5–Citation8].

Increases in episodes of DNP exposure and deaths are probably related to the availability of DNP for purchase via the internet. Industrial supplies of DNP can be repackaged into capsules convenient for human consumption and sold via multiple websites to persons seeking products to assist with weight loss, even though sale for human consumption is illegal in many jurisdictions. Common user groups include bodybuilders and body sculptors (predominantly males) as well as those with eating disorders (predominantly females). Users may purchase and ingest DNP capsules even when aware of the health risks.

This study, performed in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), aimed to better characterise international rates, trends with time and outcomes of systemic exposures to DNP. Data was sought from poisons centres, where data is collected on substances involved in clinical enquiries from health professionals and the public. Although the information collected by poisons centres has limitations, it is often the only available source of information about exposures and toxicity associated with less commonly encountered substances.

Methods

Poisons centres listed in the WHO Poisons Centre Directory [Citation9] were approached by email and asked to provide data for the period January 2010 to September 2020 (total 10.75 years) by completing a structured data collection sheet (Supplemental material). This sought information on the numbers of enquiries, total individual cases and fatal individual cases involving suspected systemic exposure to DNP, defined as ingestion or injection but not inhalation or skin exposure, broken down by sex and calendar year. They were also asked if enquiries were taken from the public as well as health professionals and the annual numbers of enquiries received for all substances. One further email was sent to each non-responding poisons centre as a reminder and data clarifications were sought from responding poisons centres when necessary.

The anonymised aggregated data returned was entered into an excel spreadsheet. Analysis of national rates of enquiries (per million population) was done where complete national data was available or when the proportion of the population covered by responding poisons centres could be estimated. Case numbers for each country were adjusted using published population statistics for 2015 and confidence intervals calculated using the Poisson method.

Results

Information was sought from poisons centres in 51 countries and data on reported DNP exposure cases were provided by at least one poisons centre in 38 countries, with complete and incomplete national data available for 31 and 7 countries respectively. Responses included consolidated national data from several poisons centres in the same country (UK, USA, Canada and France), from individual poisons centres that might cover all or part of a country, or from special administrative regions of a larger country (e.g. Hong Kong).

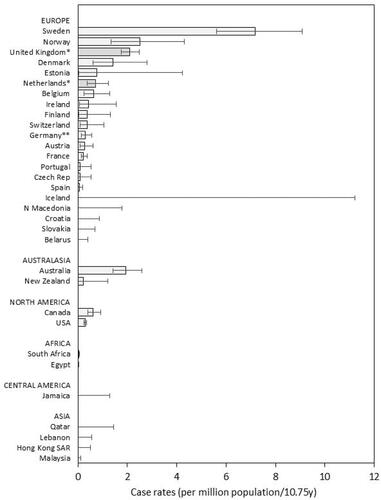

There were 456 separate DNP exposure cases reported overall, involving 303 males and 125 females (28 sex not reported). It was possible to estimate population rates for 31 countries providing complete national data and also for Germany from the estimated catchment populations of the German poisons centres that provided data. Countries in northern Europe, Australasia and North America reported the highest exposure rates, but there were substantial variations between countries, with the highest rates reported by Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, Australia and Denmark (). In contrast, very few cases were reported from poisons centres in Asia, Africa, South or Central America, although a limited number of responses were received.

Figure 1. Population-adjusted rates by reporting country of cases of suspected DNP exposure discussed with a poisons centre. *Poisons centres taking enquiries from health professionals only. **Incomplete national data – rates calculated using catchment populations of responding poisons centres. Note that zero cases were reported by individual poisons centres in Argentina, Chile, India, Italy, Saudi Arabia and Thailand; these are not included in the figure as catchment populations for these poisons centres cannot be estimated from the information available. SAR: Special Administrative Region.

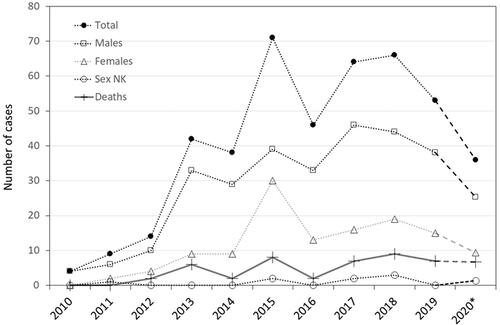

Details of the year of exposure were provided for 434 cases (301 males, 124 females, 9 sex not known). Annual numbers increased substantially between 2010 and 2015; subsequently, there were limited reductions, although annual numbers remained higher than before 2013 (). Increases in annual rates of DNP exposure have previously been reported for the UK and USA [Potts et al. 2020], but similar trends were maintained if UK and US data were omitted from the current analysis (data not shown).

Figure 2. International annual trends in cases discussed with poisons centres involving suspected DNP exposure, including deaths. *Data for 2020 are extrapolated from data collected to the end of September. NK: not known.

Follow-up of cases by poisons centres is not always done and the clinical outcome of referred cases may not be known, so information about fatalities is incomplete. Indeed, poisons centres in 5 countries (Belgium, Norway, Denmark, Austria, Estonia) stated that they were unable to provide any mortality data. The remainder reported 50 deaths (36 males, 13 females, 1 sex not reported) from 422 DNP cases referred to them. Case fatality overall was 11.9% (95% CI 9.0, 15.4) with no statistically significant difference between females (11.3%, 95% CI 6.4, 18.9) and males (12.6%; 95% CI 9.1, 17.1; Odds ratio 0.86, 95% 0.45, 1.73, p = 0.72). There were no fatal cases reported in 2010 and 2011, but reported fatalities increased subsequently ().

Discussion

This international survey of poisons centres has identified increasing numbers of referred cases of systemic exposure to DNP internationally between 2010 and 2015. Although there have been limited recent reductions in annual rates, these remain substantially higher than those reported prior to 2013. The relative ease of purchasing DNP via the internet may explain the increase in reported exposure rates. Interpol issued a global alert about DNP in 2015 [Citation10] and several agencies, including the National Food Crime Unit in the UK and the Food and Drug Administration in the USA, have taken action to close down illegal websites selling DNP [Citation11,Citation12]. This may have reduced internet sales and may explain recent reductions in DNP cases reported to poisons centres, although open sites selling DNP can still be found, the chemical may also be purchased via the darknet and cases and fatalities continue to be reported up to 2020.

As previously reported, males predominated amongst reported cases, consistent with use for bodybuilding and body sculpting. Although data from different countries may not be directly comparable, larger numbers of DNP exposures were reported by poisons centres in higher-income countries, although there were substantial international differences and some higher-income countries reported no cases. It should also be noted that only 47% of countries have a poisons centre, and they are predominantly located in high and middle-income countries [Citation9]. Although still an uncommon poison, DNP remains important because of its high case fatality, as reported in this research and previously [Citation1].

The data presented has several important limitations that should be considered in interpretation. Poisons centre data reflect the numbers of people seeking advice after exposure or suspected exposure to a substance, but enquiry numbers do not correlate directly with numbers of people developing toxicity or presenting to health services. Data were requested on numbers of individual cases, but the possibility that several enquiries about the same case might be counted as separate cases cannot be completely excluded. It is also possible that the same person may present after DNP exposure on more than one occasion, given the use of this substance by vulnerable individuals. Not all cases of exposure are discussed with a poisons centre, including some fatalities, and there may be differences between countries in this respect. Indeed, fatal DNP cases that have not been discussed with a poisons centre have been identified in the UK [Citation13] and Australia [Citation4]. In most countries, poisons centres take enquiries from the public as well as health professionals, but in some, e.g. the UK and the Netherlands, enquiries are only taken from health professionals. This may affect the numbers and patterns of enquiries received, although the UK had relatively high rates of DNP exposure in spite of this. For all these reasons, direct statistical comparisons between countries may be misleading and are further compromised by the low numbers of cases reported. Exposure data rely on patient histories, as analytical confirmation is rarely available, although the appearance of the chemical and the clinical features of DNP toxicity are characteristic. It is also a limitation that we did not collect data on the source of the motivation for use of the DNP, as this type of information is often not collected by poisons centres. Poisons centre enquiries may also be encouraged by public health messaging and other publicity and this may distort time trends. Finally, many poisons centres did not respond to the survey or were unable to provide all the data requested and the patterns of DNP exposure may differ between responders and non-responders.

Although these are important limitations, poisons centre data is useful because it is often the only source of information about rates of exposure to specific substances. This research demonstrates the value of the informal networking of poisons centres to share information, especially for substances that are uncommonly encountered and associated with a high risk of toxicity. It remains of concern that many countries do not have access to a poisons centre, as this compromises clinical case management and prevents the collection of information on substances causing toxicity in their populations.

In conclusion, the recent increases in human systemic exposures reported to poisons centres internationally and the high associated case fatality emphasise the importance of continuing efforts to restrict the availability of DNP. Countries affected should consider further legal, law enforcement and educational measures directed at reducing the risk of human consumption of this hazardous chemical.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the responding poisons centres for providing data and to Dr. Richard Brown for support in developing the questionnaire and contacting poisons centres.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Potts AJ, Bowman NJ, Seger DL, et al. Toxicoepidemiology and predictors of death in 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) toxicity. Clin Toxicol. 2021;59(6):515–520.

- Grundlingh J, Dargan PI, El-Zanfaly M, et al. 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP): a weight loss agent with significant acute toxicity and risk of death. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(3):205–212.

- Kamour A, George N, Gwynnette D, et al. Increasing frequency of severe clinical toxicity after use of 2,4-dinitrophenol in the UK: a report from the National Poisons Information Service. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(5):383–386.

- Cairns R, Raubenheimer J, Brown JA, et al. 2,4-Dinitrophenol exposures and deaths in Australia after the 2017 up-scheduling. Med J Aust. 2020;212(9):434–434.

- Hahn A, Begemann K, Burger R, et al. Centre for documentation and assessment of poisonings at the federal Institute for risk assessment – 13th report; 2006 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/364/cases_of_poisoning_reported_by_physicians_2006.pdf

- Politi L, Vignali C, Polettini A. LC-MS-MS analysis of 2,4-dinitrophenol and its phase I and II metabolites in a case of fatal poisoning. J Anal Toxicol. 2007;31(1):55–61.

- van Veenendaal A, Baten A, Pickkers P. Surviving a life-threatening 2,4-DNP intoxication: 'almost dying to be thin'. Neth J Med. 2011;69(3):154. Mar

- Personne M, Ekström M, Iveroth M. 2,4-Dinitrofenol – Ett dödligt bantningsmedel. Lakartidningen. 2014;111:996–997.

- World Health Organization. World Directory of Poisons Centres; 2021 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/poison-control-and-unintentional-poisoning/

- INTERPOL. INTERPOL issues global alert for potentially lethal illicit diet drug; 2015 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2015/INTERPOL-issues-global-alert-for-potentially-lethal-illicit-diet-drug

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA targets unlawful internet sales of illegal prescription medicines during International Operation Pangea IX; 2016 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-targets-unlawful-internet-sales-illegal-prescription-medicines-during-international-operation

- Food standards Agency 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP); 2019 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.food.gov.uk/print/pdf/node/243

- National Poisons Information Service. Report 2019–20; 2020 [cited 10 Sep 2021]. Available from: https://www.npis.org/Download/NPIS%20Report%202019-20.pdf