Abstract

Background and Objective

In the European Union, the record of cocaine-related seizures indicates an expanding supply. The purity has also been increasing. The health impact of these trends remains poorly documented, in particular, the changes and clinical manifestations of intoxication in young children. We attempted to evaluate the trend in French pediatric admissions for cocaine intoxication/exposure over an 11-year period (2010–2020).

Methods

A retrospective, national, multicenter, study of a pediatric cohort. All children less than 15 years of age admitted to a tertiary-level pediatric emergency unit for proven cocaine intoxication (compatible symptoms and positive toxicological screening) during the reference period were included.

Results

Seventy-four children were included. Forty-six percent were less than 6 years old. Annual admissions increased by a factor of 8 over 11 years (+700%) and 57% of all cases were admitted in the last two years. The main clinical signs were neurologic (59%) followed by cardiovascular symptoms (34%). Twelve patients were transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Factors significantly associated with the risk of being transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit were initial admission to the pediatric resuscitation area (P < 0.001), respiratory impairment (P < 0.01), mydriasis (P < 0.01), cardiovascular symptoms (P = 0.014), age of less than 2 years (P = 0.014). Blood and/or urine toxicological screening isolated eighteen other substances besides cocaine in 46 children (66%).

Conclusion

Children are collateral victims of the changing trends in cocaine availability, use and purity. Admissions of intoxicated children to pediatric emergency departments are more frequent and there is an increase in severe presentations. Therefore, this is a growing public health concern.

Keywords:

Introduction

Cocaine remains the second most commonly used illicit drug in Europe [Citation1]. In 2019, a record of 213 tons were seized which indicates an expanding supply in the European Union [Citation1]. In France, this high level of activity is reflected in an increase in cocaine seizures by a factor of 40 between 2015 and 2021 (643 Kg and 26.5 tons respectively) [Citation1,Citation2]. The proximity of France to Spain, the Netherlands, and Belgium affects the national territory. Two French regions are more exposed to the cocaine-related traffic routes: Occitanie, near the Spanish border, is an operating base for Colombian drug-traffickers working in Europe [Citation3]; Ile-de-France (Paris in particular) is a transit zone toward Belgium and the Netherlands, and a reception zone via Paris Airports for body packers coming from the French West Indies. Since 2015, there has also been a marked increase in air traffic (body-packers) from Guyana, while the French West Indies are a market hub via sea freight (container shipping) to mainland France (Fort-de-France to the Le Havre harbor (23 tons seized in 2021). The analysis of communal wastewaters in different European cities (Sewage analysis CORe group – Europe (SCORE)) is another indicator of the consumption trend: in France, the analysis places Paris 19th in the rank of 75 enrolled European cities [Citation4].

Cocaine purity has also been increasing over the past decade while the price has remained stable or has decreased. The average purity in France reached 66% in 2021 versus 46% in 2011 and these results are among the highest ever registered on French territory [Citation5]. Above all, there has been an expansion in home delivery of drugs by drug call centers. The health impact of these trends remains poorly documented, in particular, the clinical manifestations and severity of intoxication in young children.

The objectives of the present study were to describe the changes in French pediatric emergency department admissions for cocaine intoxication/exposure between 2010 and 2020 and to determine if there was a change in severity. The secondary objective was to describe and compare the clinical manifestations in two groups: children under 6 years old and 6 to 14 years old.

Material and methods

Study design

We performed a national, multicenter, retrospective, and observational study of a pediatric cohort.

Setting and study participants

All children less than 15-years old, admitted with proven cocaine intoxication (compatible clinical symptoms and/or history of exposure and a positive toxicological screening) to a pediatric emergency department during the reference period, were eligible. Compatible clinical symptoms to define “intoxicated” children were any acute neurological symptom(s) (drowsiness, ataxia, hypo or hypertonia, seizures, comatose status, altered consciousness, agitation, euphoria ± mydriasis) and/or adrenergic manifestations (hypertension, tachycardia, chest pain). Patients aged 15 years and over, and those with suspected, but unproven cocaine intoxication/exposure were excluded. All French university hospitals have electronic medical records. For each hospitalized patient, the diagnostic code is electronically assigned through the medical information system program using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th revision. The medical files were selected by cross-referencing the associated ICD-10 diagnosis codes for cocaine intoxication (T405 and F140) and positive urine and/or blood screening for cocaine conducted by the toxicology laboratories affiliated with each hospital.

The data collected per patient were: demographic data (age, weight, date and time of admission, mode of transportation); clinical data (vital signs on admission, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, body temperature); clinical symptoms (neurologic, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic); intoxication related data (time and mode of exposure, place of intoxication, suspected route); data related to physical examination: blood tests, lumbar puncture, head computed tomography (CT) scan, electrocardiogram (ECG), electroencephalogram (EEG), toxicological tests (blood, urine, hair) and dosing techniques (chromatography methods (liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-MS), immunochromatographic test); setting (discharged to home from the pediatric emergency department, admission to general pediatric ward, pediatric intensive care unit; notion of parental consumption and disposition (date and time of discharge from the emergency unit, total hospitalization period, social measures (child protective services, alert information, reporting to the juvenile/family court judge, foster care). Each center sent their confidential database to the study coordinator. The severity criteria were: coma (unarousable, unresponsive), seizures, respiratory failure (apnea and/or respiratory rate < 10th percentile for age, and/or endotracheal intubation), hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 5th percentile for age), hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile for age), bradycardia (< 5th percentile for age) (pulse rate < 80 beats/min (age ≤ 1 year) or pulse rate < 60 beats/min (1 < age < 6 years)), admission to the pediatric intensive care unit or a Poisoning Severity Score (PSS) of 3 [6]. The PSS is a classification scheme for cases of poisoning in adults and children, the four severity grades are PSS 0 (no symptoms or signs related to poisoning); PSS 1 (mild, transient and spontaneously resolving symptoms); PSS 2 (pronounced or prolonged symptoms), PSS 3 (severe or life-threatening symptoms) [Citation6]. To depict the changes in pediatric cocaine intoxication, our data were compared to the French national database of ICD-10 cocaine intoxication-related diagnosis codes (T405, F140) and, to the French poison control center database of calls for cocaine exposure in the same age range.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, data were entered in Microsoft Excel tables (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). Analysis was performed with StatView 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and EpiInfo 6.04fr (VF, ENSP-Epiconcept, Paris, France). In the descriptive analysis, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median with extreme values, or with 95% confidence intervals when appropriate, unless otherwise indicated. To compare qualitative variables, a χ2 test (Mantel-Haenszel) was used and a 2-tailed Fischer exact test if the expected value was <5. For quantitative independent variables, a paired student t-test was applied. A nonparametric Kruskall–Wallis test was performed in case of non-normal distribution. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Ethical and regulatory considerations

According to French law on ethics, patients were informed that their codified data will be used for the study. According to the French ethic and regulatory law (public health code) retrospective studies based on the exploitation of usual care data shouldn’t be submitted at an ethics committee but they have to be declared or covered by reference methodology of the French National Commission for Informatics and Liberties. A collection and computer processing of personal and medical date was implemented to analyze the results of the research. Toulouse University Hospital signed a commitment of compliance to the reference methodology MR-004 of the French National Commission for Informatics and Liberties. After evaluation and validation by the data protection officer and according to the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016), this study completing all the criteria, it is registered in the data study registry of the Toulouse University Hospital (registration number: RnIPH 2021-146) and cover by the MR-004 (National Commission for Informatics and Liberties number: 2206723 v0). This study was approved by Toulouse University Hospital and confirmed that ethics requirements were totally respected in the above report.

Results

Descriptive analysis

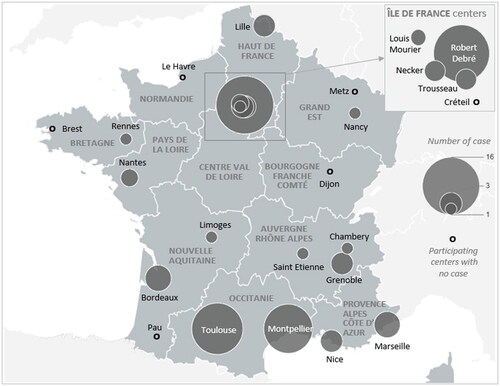

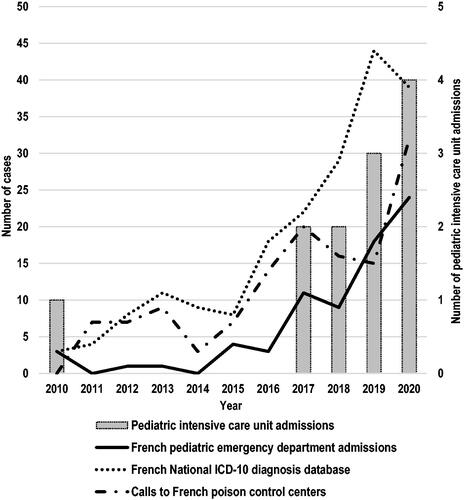

Twenty-four pediatric emergency departments (80% of the national pediatric emergency departments) from 18 French districts participated in the study. During the study period, 74 children matching the inclusion criteria were admitted. The analytical technique was reported in 48 cases: LC-MS/MS was the most frequently used (63%), GC-MS (27%), and immunochromatographic test 10.4%. The age analysis showed a bimodal distribution: 46% were less than 6-years-old and, 38% of patients were 14-years-old, 16% of children were aged between 6 and 13-years-old. illustrates the national geographical distribution of participating centers and their respective number of cases. The main demographic characteristics are summarized in . Annual admissions increased by a factor of 8 over 11 years and 57% of all cases were admitted in the last two years of the study period. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of severe cases followed the trend (), 83% of them were admitted between 2017 and 2020. The place of intoxication was available in 47 medical files: the parental home (n = 30) was frequent among young children (age < 6 years, n = 26) while public area (street, metro, park) were reported in 17 cases mainly by teenagers (94%). Ingestion was the main route of intoxication (51%), it was not specified for the majority of the other patients (39%) and, four newborns (1-day-old, 4-days-old, 8-days-old, 29-days-old) were assumed being contaminated while breast-fed by mothers who used cocaine. Twenty-eight percent of the patients (n = 21) had no symptoms. The clinical signs on arrival at the pediatric emergency department were predominantly neurologic (59%) followed by cardiovascular symptoms (34%). All symptoms on admission are listed in and were compared to the previous study from Armenian et al. [Citation7] previous study. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) distribution showed: GCS 15 (n = 44), GCS between 11 and 14 (n = 12), GCS less than 11 (n = 8), unspecified (n = 10). Among symptomatic children (n = 53), the distribution of the PSS was: PSS 1 (n = 23), PSS 2 (n = 12), PSS 3 (n = 18). Most of the children were hospitalized (76%), 18 children were discharged to home from the pediatric emergency department. Twelve patients were transferred to a PICU (age < 6 years, n = 8) and two required assisted ventilation (one case of status epilepticus in a 10-month-old and a 1-day-old apneic baby of a mother who used cocaine, both cases were positive only for cocaine). Among severe cases, 5 patients were positive for other substances: paracetamol (n = 1), levamisole (n = 1), cannabis (n = 3), methylenedioxymetamfetamine (n = 1) and, all cannabis-positive patients (n = 3) were in comatose status, their age distribution was (1-year-old (n = 2), 9-year-old and 14-year-old). Basic metabolic panel blood tests (77% of patients) revealed abnormalities in 63%. These included hyperglycemia (n = 11), metabolic acidosis (n = 11), hypoglycemia (n = 10), rhabdomyolysis (n = 3), abnormal troponin concentration (n = 5) and dehydration (n = 4). Additional procedures included: ECG (n = 28), head CT scan (n = 19), EEG (n = 6), abdominal ultrasound (n = 5), lumbar puncture (n = 3), digestive endoscopy (n = 1) and cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (n = 1). Three teenagers had significant abnormal explorations: a fall from a window (posterolateral skull fracture with pneumocephalus), a jail fight (lamina papyracea fracture and intraorbital hematoma) and, an unaccompanied minor found unconscious in the street (C1-C2 vertebral subluxation). One 3-year-old child had an abnormal ECG with a diffuse ST segment elevation, a high troponin concentration (310 µg/L) in the context of parental crack use and carbon monoxide exposure due to a house fire. In addition to cocaine detection, blood and/or urine toxicological screening (GC-MS or LC/MS-MS) was performed in 70 cases. Eighteen other substances besides cocaine were isolated in 46 children (66%), mostly teenagers (72%) (). The other substances identified were cannabis (65%), benzodiazepines (26%) and amfetamines (17%). Half of the asymptomatic patients were also positive for other subtances besides cocaine. Parental cocaine consumption was specified in 44 records (88% in the age group < 6 years) and 57% of these parents were declared users (70% of parents of young children). Ten children were unaccompanied minors. Social or legal measures were taken: a referral to child protective services (n = 23), a written report for special concern to child protection services (n = 36), a placement in foster care by court order (n = 21)

Figure 1. French regional geographic distribution of participating centers (n = 24, one circle corresponds to one center) and their respective cases of cocaine-related pediatric exposures/intoxications (2010–2020).

Graph 1. Distribution of cocaine-related admissions in French pediatric emergency departments compared to data from the French ICD-10 diagnosis base and to data from cocaine exposure-related calls to the French poison control centers during the study period (2010–2020). ICD- 10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision.

Table 1. Main characteristics of pediatric patients admitted for cocaine intoxication/exposure between 2010 and 2020 (percentages in column).

Table 2. Clinical findings among cocaine intoxicated pediatric patients admitted between 2010 and 2020 to French pediatric emergency departments compared to the Armenian et al. [7] study (percentage in columns).

Table 3. List of other substances detected by toxicologic analysis in children with cocaine exposure/intoxication.

Comparative analysis

We compared data according to the period of admission (2019–2020 (n = 42) versus 2010–2018 (n = 32)), according to age (age < 6 years (n = 34) older children (n = 40), and the risk of being transferred to the PICU (n = 12 versus n = 62).

Admission during the last two years (2019-2020)

The last two years of the study period were characterized by intoxications with fewer cardiovascular symptoms (24% vs 47%, OR 0.4 [0.1–0.9], P = 0.04), more admissions during the summer (40% vs 25%, OR 3.4 [1.2–9.8], P = 0.02) and a trend of more admissions during the weekend (40% vs 31%, OR 2.5 [0.9–6.9], P = 0.08)

Age group < 6 years

Younger children differed from older children by more home exposure/intoxication (P < 0.0001) and more reports of special concerns to CPS (OR 15.4 [4.9–48.1], P < 0.0001) (). They experienced less drowsiness (9% vs 30%, OR 0.2 [0.1–0.9], P = 0.03), showed more tachycardia (32% vs 5%, OR 9.1 [1.8–44.7], P = 0.007) and more respiratory symptoms (18% vs 2%), OR 8.4 [1.0–73.5], P = 0.04). They were more frequently hospitalized (94% vs 60%, OR 10.7 [2.2–50.9], P = 0.003).

Risk of being transferred to a pediatric intensive care unit

Factors significantly associated with this risk included initial admission to the pediatric resuscitation room (67% vs 2%, OR 13.5 [3.3–55.4], P < 0.001), respiratory impairment (33% vs 5%, OR 9.8 [1.8–52.2], P < 0.01); mydriasis (50% vs 10%, OR 9.3 [2.3–38.2], P < 0.01); cardiovascular symptoms (67% vs 27%, OR 5.3 [1.4–19.9], P = 0.014); more than one symptom (neurological, respiratory, cardiovascular) (67% vs 18%, OR 9.3 [2.4–36.3], P < 0.01); and, being younger than 2-years-old (67% vs 10%, OR 5.3 [1.4–19.9], P = 0.014).

Data were also compared to the French national base of ICD-10 cocaine intoxication-related diagnosis codes. Twenty-four pediatric emergency units in the study represented 38% of all cases registered in this national database (n = 195) while 121 other cases were admitted to 630 emergency units spread across the French territory. Compared to the French population of children less than the age of 15 years and less than the age of 6 years in 2010 and 2020, the overall national rate per capita for cocaine exposure/intoxication-related emergency admissions progressed from 0.3 to 5.9 per million (age < 15 years) and from 0 to 3 per million (age < 6 years) while the number of children in each age group decreased between 2010 and 2020 (respectively −5% and −8%). Compared to pediatric emergency department admissions for children under 15 years of age between 2013 and 2020 (data available online on the annual statistics of public or private health centers www.sae-diffusion.sante.gouv.fr/), cocaine-related pediatric emergency department visits increased from 0.7 to 3.3/100,000 admissions per year. Data were compared to cocaine-related calls received by the French poison control centers during the same period. Between 2010 and 2020, the French poison control centers received 130 calls for cocaine exposures (age < 6 years (57%)), 48% of cases in the last three years. The number of cocaine-related calls to the French poison control centers increased by a factor of 32.

Multivariate analysis

Factors independently associated with the risk of pediatric intensive care unit transfer were identified using a multiple-stepwise logistic regression model. All variables showing P < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were entered in the model: age < 2 years; neurological, respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms, presenting more than one of these three symptoms; mydriasis, summer and nighttime admission. In the final model, three variables continued to be associated with the risk of pediatric intensive care unit transfer: summer admission (adjusted OR (aOR) 5.0 [1.1–22.3], P = 0.03); presenting more than one symptom (neurologic, cardiovascular or respiratory symptoms) (aOR 4.9[1.2–19.9], P = 0.026); age < 2 years (aOR 4.5[1.0–20.1], P = 0.046).

Discussion

The increase in admissions to French pediatric emergency units for cocaine intoxication/exposure indicates a greater availability in the general population. During the first COVID year (2020), the national pediatric emergency admission rate was even higher than the previous year (3.3/100,000 and 2.8/100,000 admissions respectively). The increase in the severity of cases could be associated with greater purity [Citation5] and the presence of other toxic substances such as co-intoxicants and/or adulterants. A large majority of cases (84%) were registered in 2017–2020 which is consistent with a recent publication in the United States by Becker et al. [Citation8]. This trend follows the expansion of the cocaine market in France [Citation9]. Cocaine is rapidly metabolized in the liver to benzoylecgonine and ecgonine methyl ester by plasma cholinesterases [Citation7,Citation10]. The average cocaine half-life is 90 min and 6 to 8 h for benzoylecgonine [Citation10,Citation11]. In infants, the half-life is longer due to the decreased activity of plasma cholinesterases [Citation12]. Adrenergic overactivity typifies cocaine intoxication and the toxicity is caused by the direct effects of sodium channel inhibition and the indirect effects of inhibition of serotonin and catecholamine uptake [Citation10,Citation13–15]. In young children, intoxication is usually non-intentional, and, neurological or cardiovascular effects are the most common. Ten to 30% of young children (age < 6 years) are asymptomatic [Citation6–8,Citation16]. Neurologic effects include changes in mental status, lethargy, excitability, psychomotor agitation, ataxia, and seizures (cocaine lowers the seizure threshold) [Citation7,Citation10,Citation15–22]. Seizures (10% to 36%) may be partial or generalized and can progress to status epilepticus [Citation17,Citation19–21, Citation23,Citation24]. Seizures can occur more than 12 h after cessation of exposure and are usually attributed to benzoylecgonine [Citation13]. A bilateral slow responsive mydriasis has been reported in 3% to 18% of pediatric cases [Citation7,Citation15–19,Citation25,Citation26]. Several patients were positive for other substances () and one might assume that severe presentations could be related to the association of these substances in addition to cocaine. Among such cases (12 children), 5 patients were positive for other substances (paracetamol, levamisole, cannabis, methylendioxymetamfetamine). The comatose status of three of these patients with cannabis detection seems more presumably related to the cannabis effect than cocaine. Nevertheless, in the pediatric cohort published by Armenian et al. [Citation7], 22% had a depressed level of consciousness with no other drugs mentioned besides cocaine. When compared to our results, the clinical presentations of their cohort differ by a greater rate of cardiovascular and neurological symptoms. This could be related to a different purity between the two study periods and countries: an average of 66% in France versus 56% in the USA (World Drug Report 2004 www.unodc.org/pdf/WDR_2004/Chap5_coca.pdf) and the side effects of adulterants. The most frequent cardiovascular effects are sinus tachycardia and moderate hypertension (18% to 50%) [Citation7,Citation16]. A case of Brugada syndrome in a 16-month-old intoxicated child was recently published [Citation27]. Other cardiovascular effects (myocardial infarction, coronary artery vasospasm, chest pain, dysrhythmias) have been described in teenagers after intentional exposure [Citation11,Citation13,Citation28]. Cocaine-related symptoms in young children also include a significant amount of respiratory [Citation7] and gastrointestinal manifestations (12 to 17%) (vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea) [Citation7,Citation26]. Intoxication has been associated with intestinal ischemia and necrosis (acute hemorrhagic diarrhea, abdominal distension, vomiting) after the ingestion of a crack in a 4-year-old girl [Citation29]. Hyperthermia results from increased motor activity and/or impaired heat dissipation due to vasoconstriction [Citation24]. Rhabdomyolysis is rare (3–4%) and related to direct muscle toxicity, seizures or serotonin syndrome. Severe outcomes have been reported in 24% to 39% of children less than 6 years old [Citation6,Citation7]. Some pediatric cocaine-related deaths have been reported outside the neonatal period [Citation30,Citation31]. Urine detection by immunoassay is very sensitive, there are no known false-positive cases [Citation10]. Urine and serum toxicology screens are useful to detect cocaine and its metabolites as well as other substances [Citation32,Citation33]. In our study, the toxicology screen-detected other substances in 16 toddlers (47% of the same age group). This result is remarkable as Becker et al. [Citation8] described multiple-substance exposures in 11.8% of children aged less than 6-years-old in the United States. Sixty-seven percent of children with other detected substances were admitted between 2018 and 2020. Adulterants are divided into two categories: inert compounds (e.g., talc, milk powder, cornstarch) that increase profit using a less active substance for the same price and, active molecules that increase cocaine effects (levamisole (central nervous system synergetic effect), caffeine (enhanced psychostimulant effect), lidocaine (cocaine-like effects)) or minimize (hydroxyzine (sedative, antiemetic, hypnotic, anxiolytic), phenacetine (analgesic, slightly euphoric)) [Citation32,Citation33]. Levamisole, was detected in up to 80% of the samples in 2016–2017 [Citation34]. In case of intoxication, the treatment is mainly supportive. Regular antipyretic medications do not help to decrease temperature as hyperthermia is a consequence of muscular activity. Sinus tachycardia does not usually require intervention. Benzodiazepines are effective in the first-line management of seizures, psychomotor agitation and related tachycardia or hypertension. In the case of moderate to severe hypertension, vasodilators are recommended [Citation11,Citation19,Citation24]. Because of their non-specific nature, cocaine-related symptoms are difficult to correlate to poisoning in infants. For this reason and due to the increase in cocaine availability, we agree with the recommendations by Armenian et al. [Citation7] to test children less than 6-years-old presenting with new-onset unexplained seizures, agitation, unexplained persistent tachycardia, altered mental status with no previous central neverous system impairment history. In France, we also recommend drug testing in children admitted to the emergency department for altered mental status and/or seizures when previously healthy [Citation35].

Bias and limitations

Because of the retrospective nature of the study, some data were insufficient (e.g., parental cocaine consumption, estimated time of exposure/intoxication). Some children could have been admitted to a non-pediatric emergency department setting but usually, because of the alarming clinical presentation, they were transferred to the nearest regional pediatric emergency department. Twenty-four pediatric emergency departments in the study admitted 38% of all national cases registered according to the French national ICD-10 diagnosis database while other cases were admitted to 630 emergency units spread across the French territory. The regional distribution of cases has to be cautiously interpreted: two regions seemed to have disproportionate intoxications/exposures (Ile-de-France and Occitanie) as they cumulated 50 of the 74 cases. All their university pediatric hospitals have participated while in other regions, none or part of them did. Benzoylecgonine has a half-life of 12 h, it can be detected in blood and/or urine for about 48 h after last use, screening for benzoylecgonine implies recent exposure but not necessarily acute toxicity. Co-intoxicants or adulterants were detected in 62% (n = 46) of the screened patients (n = 70), 16 children under 6 years old (47%), which means that clinical symptoms could also have been related to the toxicity of other substances.

Conclusion

Children are collateral victims of the changing trends in cocaine availability, use and purity. Admissions of intoxicated children to pediatric emergency departments are more frequent and there is an increase in severe presentations (24% of young children (age < 6 years) had severe intoxication and were admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit. The major concern is the presence of other substances among 47% of the 6-year-old group. In this group, a parent's use was already known in 70%. Therefore, this is a growing public health concern. Better targeting this specific population for prevention may help to inform them about this collateral risk for their young children.

Author’s contribution

Isabelle Claudet: Prof. Claudet conceived the project and the study design, analyzed results, interpreted data, and drafted the initial manuscript.

Jean-Christophe Gallart: Dr. Gallart performed all the data extraction and analysis from the national database of French poison control centers, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript

Caroline Caula, Gaelle Tourniaire, Marion Lerouge-Bailhache, Anne-Pascale Michard-Lenoir, Antoine Tran, Aline Maleterre, Frédéric Huet, Damien Dufour, Nicolas Billaud, Alexandra David, Marie Di Patrizio, Mathilde Granjon, Grégoire Benoist, Christine Laguille, Marie-Aline Guitteny, Bénédicte Vrignaud, Romain Basmaci, Marie Dampfhoffer, François Dubos, Hélène Chappuy, Philippe Minodier, Nicolas Médiamolle, Camille Bréhin: Drs Caroline Caula, Gaelle Tourniaire, Marion Lerouge-Bailhache, Anne-Pascale Michard-Lenoir, Antoine Tran, Aline Maleterre, Frédéric Huet, Damien Dufour, Nicolas Billaud, Alexandra David, Marie Di Patrizio, Mathilde Granjon, Grégoire Benoist, Christine Laguille, Marie-Aline Guitteny, Martine Balençon, Bénédicte Vrignaud, Romain Basmaci, Marie Dampfhoffer, François Dubos, Hélène Chappuy, Philippe Minodier, Nicolas Médiamolle, and Camille Bréhin collected data, critically reviewed, substantially participated in data analysis and revised the manuscript.

All listed authors contributed to data collection, critically reviewed and, substantially participated in data analysis. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr Erick Grouteau for his expertise in statistics and his critical review of the results and pertinence of statistical tests. We also acknowledge Mrs. Françoise Auriol for her help with the ethical and regulatory considerations of the study and Dr. Olivier Azema for his assistance in the realization of the figures.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Data availability statement

Deidentified individual participant data will not be made available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- European Drug Report 2021 – Trends and Developments. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/13838/TDAT21001ENN.pdf. (Available 08/22/2022)

- European Drug Report 2020 – Trends and Developments. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2020_en. (Available 08/22/2022)

- Mc Dermott J, Bargent J, den Held D, et al. The Cocaine Pipeline to Europe – © 2021 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. https://insightcrime.org/investigations/cocaine-pipeline-europe/. (available 08/22/2022)

- Wastewater analysis and drugs—a European multi-city study. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/html/pods/waste-water-analysis_en. (Available 08/22/2022)

- Gérome C, Gandilhon M. Psychoactive substances, users and markets. Recent trends (2019–2020) (French). Tendances n°141, OFDT, 2020http://www.ofdt.fr/publications/collections/periodiques/lettre-tendances/substances-psychoactives-usagers-marches-tendances-recentes-2019-2020-tendances-141-decembre-2020/. (Available 08/22/2022)

- Persson HE, Sjöberg GK, Haines JA, et al. Grading of acute poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(3):205–213.,

- Armenian P, Fleurat M, Mittendorf G, et al. Unintentional pediatric cocaine exposures result in worse outcomes than other unintentional pediatric poisonings. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(6):825–832.

- Becker S, Spiller HA, Badeti J, et al. Cocaine exposures reported to United States poison control centers, 2000–2020. Clin Toxicol. 2022;28:1–11.

- Gandilhon M, Janssen E, Palle C. Cocaine, crack, freebase. In Drugs and addictions. Essential data. Frenc observatory for drugs and toxicomania. pp 124–128, 2019 http://www.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/DADE2019.pdf. (Available 08/22/2022)

- Heidemann SM, Goetting MG. Passive inhalation of cocaine by infants. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1990;38:252–254.

- Havakuk O, Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA. The cardiovascular effects of cocaine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):101–113.

- Cregler LL. Protracted elimination of cocaine metabolites. Am J Med. 1989;86(5):632–633.

- Lipton JW, Mangan KP, Silvestri JM. Acute cocaine toxicity: pharmacology and clinical presentations in adult and pediatric populations. J Pharm Pract. 2000;2:159–169.

- Elkattawy S, Alyacoub R, Al-Nassarei A, et al. Cocaine-induced heart failure: report and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11(4):547–550.

- Ernst AA, Sanders WM. Unexpected cocaine intoxication presenting as seizures in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(7):774–777.

- Juanena C, Pan M, Valdez M, et al. Cocaine exposure among children aged less than 5 years: a case series (Spanish). Arch Pediatr Urug. 2018;89:366–373.

- Mott SH, Packer RJ, Soldin SJ. Neurologic manifestations of cocaine exposure in childhood. Pediatrics. 1994;93(4):557–560.

- Miramont S, Alvarez JC, Bourgogne E[, et al. Passive cocaine inhalation by a 25-month-old child. . Arch Pediatr. 2013;20(6):654–656.

- Conway EE, Jr, Mezey AP, Powers K. Status epilepticus following the oral ingestion of cocaine in an infant. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1990;6:189–190.

- Chaney NE, Franke J, Wadlington WB. Cocaine convulsions in a breast-feeding baby. J Pediatr. 1988;112(1):134–135.

- Chasnoff IJ, Lewis DE, Squires L. Cocaine intoxication in a breast-fed infant. Pediatrics. 1987;80:836–838.

- Garland JS, Smith DS, Rice TB, et al. Accidental cocaine intoxication in a nine-month-old infant: presentation and treatment. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1989;5(4):245–247.

- Rivkin M, Gilmore HE. Generalized seizures in an infant due to environmentally acquired cocaine. Pediatrics. 1989;84(6):1100–1102.

- Glauser J, Queen JR. An overview of non-cardiac cocaine toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):181–186.

- Pinto JM, Babu K, Jenny C. Cocaine-induced dystonic reaction: an unlikely presentation of child neglect. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(9):1006–1008.

- Edell DS, McSwain M. Cocaine poisoning: an easily missed diagnosis in an infant. Clin Pediatr . 1993;32(12):746–747.

- Ohns MJ. Unintentional cocaine exposure and Brugada syndrome: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2020;34:606–609.

- McCord J, Jneid H, Hollander JE, et al. American heart association acute cardiac care committee of the council on clinical cardiology. Management of cocaine-associated chest pain and myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American heart association acute cardiac care committee of the council on clinical cardiology. Circulation. 2008;117:1897–1907.

- Riggs D, Weibley RE. Acute hemorrhagic diarrhea and cardiovascular collapse in a young child owing to environmentally acquired cocaine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1991;7:154–155.

- Havlik DM, Nolte KB. Fatal "crack" cocaine ingestion in an infant. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2000;21:245–248.

- Cravey RH. Cocaine deaths in infants. J Anal Toxicol. 1988;12(6):354–355.

- Di Trana A, Montanari E. Adulterants in drugs of abuse: a recent focus of a changing phenomenon. Clin Ter. 2022;173:54–55.

- Gameiro R, Costa S, Barroso M, et al. Toxicological analysis of cocaine adulterants in blood samples. Forensic Sci Int. 2019;299:95–102.

- Midthun KM, Nelson LS, Logan BK. Levamisole-a toxic adulterant in illicit drug preparations: a review. Ther Drug Monit. 2021;43(2):221–228.

- Claudet I, Mouvier S, Labadie M, et al. Unintentional cannabis intoxication in toddlers. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170017.