Abstract

Introduction

Chlorpromazine, one of the oldest antipsychotic medications, remains widely available and is still taken in overdose. We aimed to investigate the clinical effects of chlorpromazine overdose and determine if there is a relationship between the reported dose ingested and intensive care unit admission or endotracheal intubation.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients admitted to our toxicology tertiary referral hospital with chlorpromazine overdose (reported dose ingested greater than 300 mg) between 1987 and 2023. We extracted demographic information, details of ingestion, clinical effects and complications (Glasgow Coma Scale, hypotension [systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg], delirium, dysrhythmias), length of stay, intensive care unit admission, and endotracheal intubation.

Results

There were 218 chlorpromazine overdose cases, with presentations decreasing in frequency over the 36 years. The median age at presentation was 32 years (interquartile range: 25–40 years) and 143 (61 per cent) were female. The median reported dose ingested was 1,250 mg (interquartile range; 700–2,500 mg). The majority of presentations (135; 62 per cent) involved reported co-ingestion of other medications, typically benzodiazepines, paracetamol or antipsychotics. There were 76 (35 per cent) chlorpromazine alone ingestions in which there was a slightly higher median reported dose ingested of 1,650 mg (interquartile range: 763–3,000 mg) compared to the reported co-ingestion group, median reported dose ingested of 1,200 mg (interquartile range: 700–2,100 mg). Of all presentations, 36 (27 per cent) had a Glasgow Coma Scale less than 9, 50 (23 per cent) were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 32 (15 per cent) were endotracheally intubated. There was a significant difference in the median reported dose ingested between patients intubated (2,000 mg; interquartile range: 1,388–3,375 mg) and those not intubated (1,200 mg; interquartile range: 644–2,050mg; P < 0.001), and between those admitted to the intensive care unit and not admitted to the intensive care unit (P < 0.0001). The median reported dose ingested in seven chlorpromazine alone presentations who were intubated was 2,500 mg (interquartile range: 2,000–8,000 mg, range: 1,800–20,000 mg). Eighteen (8 per cent) patients developed delirium, eight (4 per cent) had hypotension, three had seizures, and there was one death.

Discussion

Almost one quarter of cases were admitted to the intensive care unit and over half of these were intubated. Whist the decision to admit to an intensive care unit or intubate a patient is based on clinical need, there was a significant association between reported dose ingested and requirement for endotracheal intubation. Both the frequency of presentation and reported dose ingested declined after 2013. The major limitations of the study were a retrospective design and no analytical confirmation of ingestion.

Conclusions

We found that the most common effect of chlorpromazine overdose was central nervous system depression and that endotracheal intubation was associated with larger reported doses ingested, particularly in single chlorpromazine ingestions.

Introduction

In the early 1950s, chlorpromazine was the first antipsychotic medication successfully used to treat schizophrenia and has been credited with changing the face of psychiatry [Citation1]. Chlorpromazine belongs to the class of phenothiazine antipsychotics, commonly used to treat various psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and severe anxiety. Chlorpromazine works by blocking dopamine receptors in the brain, which helps alleviate symptoms of psychosis and stabilizes mood. Given the trade name ‘Largactil’ for its ‘large activity’ on different receptors, in overdose there is the potential for sedation, cardiotoxicity (dysrhythmias and hypotension), extrapyramidal side-effects and delirium [Citation2–5]. Beyond its psychiatric uses, chlorpromazine is also used to manage nausea and vomiting, particularly in the context of chemotherapy or surgery, and has also been used for acute management of migraines [Citation6, Citation7]. Despite the availability of newer antipsychotic medications, chlorpromazine remains an important treatment of various psychiatric conditions, especially in settings where cost-effectiveness and accessibility are crucial considerations.

Chlorpromazine overdoses have been reported since it was first introduced [Citation8], but there is limited information on clinical effects and outcomes. Some information can be gained from publications that include overdoses of a number of different antipsychotics including chlorpromazine, but this is limited information often only for specific clinical effects, such as cardiotoxicity [Citation4, Citation9]. Despite chlorpromazine being an older antipsychotic, it remains available and continues to be used for psychiatric and non-psychiatric conditions. This has meant that it continues to be taken in overdose, for which we have limited evidence of clinical effects and treatment.

We aimed to investigate the spectrum and severity of effects in chlorpromazine overdose and determine if there is a relationship between reported dose ingested and complications, including admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and endotracheal intubation.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was an observational case series of all chlorpromazine overdose presentations to a regional toxicology treatment unit, which is the primary referral centre for over 500,000 people. Clinical and demographic information is obtained on all patients upon admission to the toxicology service. A clinical data collection form is used at the time of presentation by emergency staff. The information is then entered into a database. Exemption for use of the database and medical records as an audit has been previously approved by the Hunter and New England Research Ethics Committee.

Selection of participants

All presentations to the toxicology service between January 1987 and December 2023 were reviewed. We extracted the annual numbers for all first generation antipsychotic overdoses, enabling a comparison of trends over time. We then only included chlorpromazine admissions, in which the patient ingested more than 300 mg of chlorpromazine, for the main analysis. The dose 300 mg was chosen because it is the defined daily dose (the average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indications in adults) for oral chlorpromazine [Citation10]. Confirmation of chlorpromazine ingestion was established from the patient’s history taken at least twice, as well as collateral history from family, emergency medical services, other health care providers and empty medication packets. We additionally reviewed all first generation antipsychotic presentations (including chlorpromazine) to our unit as an overdose with no limitation on dose ingested, to compare the number of presentations of different first generation antipsychotics.

Measurements

The following data were extracted from the database using standard database queries: patient demographic information (age and sex), details of ingestion (time of ingestion, time of presentation, estimated reported ingested dose [mg] and co-ingestants), clinical effects (heart rate, blood pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS], seizures and delirium), electrocardiogram (ECG) characteristics (heart rate, QRS complex duration and QT interval duration), ICU admission, length of stay and treatment given (decontamination and ventilatory support). Further detailed information on the lowest GCS was obtained from the medical record by one author. Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg. Delirium was determined at the bedside by a clinical toxicologist reviewing the patient for orientation once alert (i.e., not assessed when sedated or intubated). Alcohol was only included as a co-ingestant if there was also an acute ingestion of more than 100 g of alcohol within 1 – 2 h of chlorpromazine ingestion.

Patients were admitted to the ICU on the decision of the intensivist and therefore was subjective, but usually guided by the need for either ongoing airway support (endotracheal intubation and ventilation), decreased level of consciousness unable to be supported elsewhere or requirement for cardiac support, such as inotropes. The decision to admit to the ICU might have changed between 1987 and 2023. Criteria for ICU admission were determined by the toxicology unit and discharge could occur 24 h a day. Admission to a psychiatric hospital, if required, was dependant on bed availability and could result in an extended toxicology length of stay.

The following outcomes were used: decreased level of consciousness or coma measured as a GCS of <9; requirement for ICU admission; seizure activity; hypotension, dysrhythmias, delirium, and hospital length of stay.

Data analyses

All continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) because some of the data was not normally distributed (e.g., length of stay) and it is easier to interpret if all continuous variables are reported with the same summary statistics. Continuous variables were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. All statistical and graphical analyses were done in GraphPad Prism version 10.2.2 (397) for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com.

Results

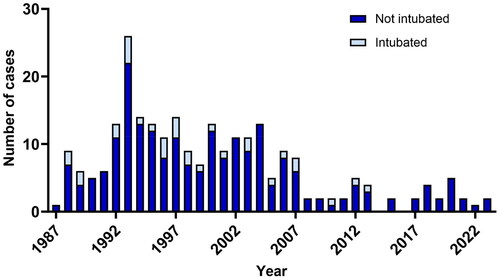

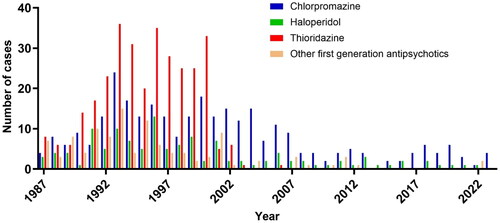

A total of 305 presentations of chlorpromazine overdose occurred over the 36-year period. The trend in presentations decreased over three decades, mainly declining from 2007 (). Comparatively, there appeared to be a greater decrease in overdoses of thioridazine and other first generation antipsychotics especially since 2001; . Undocumented doses or reported doses ingested <300 mg were excluded, leaving 218 cases. The median age at presentation was 32 years (IQR: 25–40 years) and 143 (61%) were female. The median reported dose ingested was 1,250 mg (IQR; 700–2,500 mg) ().

Figure 1. Total number of chlorpromazine overdose presentations by year from 1987 to 2023, and number of these intubated (light blue) or not intubated (dark blue) each year.

Figure 2. Number of first generation antipsychotic overdose presentations by year from 1987 to 2021. Chlorpromazine (blue), haloperidol (green), thioridazine (red) and other first generation antipsychotics (trifluoperazine, fluphenazine, pimozide; orange).

Table 1. Severity of effects and outcome differences between all 218 chlorpromazine overdose cases, chlorpromazine alone ingestions, chlorpromazine overdoses with co-ingestions, requiring intensive care unit care and endotracheal intubation or not.

The majority of presentations (142; 65%) involved reported co-ingestion of other medications, typically benzodiazepines, other antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers, and simple analgesics. The most common co-ingestants were diazepam, paracetamol, clonazepam, temazepam, and sodium valproate. The median reported dose of chlorpromazine ingested in the reported co-ingestion group was 1,200 mg (IQR: 700–2,100 mg), and their length of stay was 21 h (IQR: 15–37 h). There were 76 (35%) chlorpromazine alone ingestions. Patients who ingested chlorpromazine alone had a slightly greater median reported ingested dose of 1,650 mg (IQR: 763–3,000 mg) compared to the reported co-ingestion group (). The chlorpromazine alone group had a shorter length of stay of 17 h (IQR: 11–24 h). The median reported dose ingested in the years up to and including 2007 was 1,500 mg (IQR: 700–2,500 mg), whereas the median reported dose ingested decreased after 2007 to 1,100 mg (IQR: 700–2,200 mg).

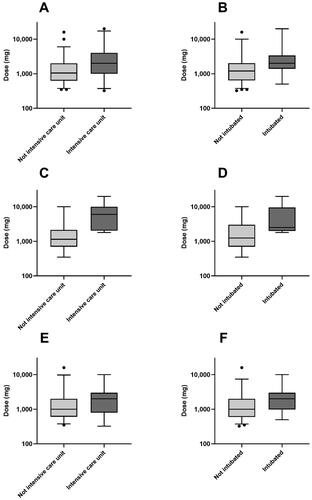

Of the 218 presentations, 36 (17%) had a GCS <9, 51 (23%) were admitted to the ICU and 32 (15%) were endotracheally intubated. Intensive care unit admission was more common in the reported co-ingestion group with 38 (27%) cases admitted to the ICU, compared to only 12 (15%) cases admitted to the ICU in the chlorpromazine alone group (). Endotracheal intubation was also more likely in the reported co-ingestion group, with 25 (18%) cases versus seven (9%) cases in the alone ingestion group being endotracheally intubated (). No patients were intubated after 2013. There was a significant difference in the median reported dose ingested between patients intubated (2,000 mg; IQR: 1,388–3,375 mg) and those not intubated (1,200 mg; IQR: 644–2,050 mg; P < 0.001; ), and between those admitted to the ICU and not admitted to the ICU (P < 0.0001; ), irrespective of reported co-ingestion. The median reported dose ingested in seven chlorpromazine alone presentations who were intubated was 2,500 mg (IQR: 2,000–8,000 mg, range: 1,800–20,000 mg), compared to a median reported dose ingested of 1,250 mg (IQR: 700–3,000 mg, range: 350–10,000 mg) in 69 patients with chlorpromazine alone ingestions who were not intubated (). The last chlorpromazine only ingestion, admitted to the ICU without endotracheal intubation, occurred in 2002, and was a 6,000 mg ingestion.

Figure 3. Graphs (box and whiskers) of reported doses ingested (logarithmic scale) in all chlorpromazine overdoses (A, B), chlorpromazine alone ingestions (C, D) and chlorpromazine overdoses with co-ingestions (E, F), among patients admitted to intensive care unit or not (A, C, E) and intubated or not (B, D, F). Horizontal lines demonstrate medians, with the box representing the interquartile range and the whiskers representing the 2.5 percentile (lower) and the 97.5 percentile (upper).

Other clinical effects and complications were less common, with delirium in 18 (8%) presentations and hypotension in eight (4%) presentations, which was the same for chlorpromazine alone ingestions (). Only one presentation required inotropes, involving co-ingested quetiapine. There were no dysrhythmias. The QT duration:heart rate pairs were previously extracted in presentations before May 2013, and were presented elsewhere [Citation11]. Seizures occurred in three cases: one ingested 6,000 mg with alcohol, another ingested 10,000 mg alone and the third ingested 800 mg with 6,000 mg quetiapine, and unknown amounts of risperidone and sertraline.

One patient died from a cardiac arrest immediately after extubation. The death was reported to be secondary to ischaemic heart disease on post-mortem, and massive pulmonary embolus was excluded. The patient had ingested chlorpromazine 1,000 mg, valproate 4,000 mg, lithium 2,500 mg, and diazepam 30 mg.

Discussion

We showed a decrease over time in the number of patients presenting with chlorpromazine overdose, but there still remained a constant number of patients presenting after 2007 (). There appeared to be a much more dramatic decrease in overdoses of thioridazine and other first generation antipsychotics, especially since 2001 (). This is consistent with other studies that have looked at prescribing and overdose patterns in our region, noting a reduction in both prescribing and overdose of first generation antipsychotics (such as chlorpromazine), in favour of newer generation antipsychotics, which have continued to rise rapidly [Citation12]. A more detailed review of the first generation antipsychotic group () showed that the three largest first generation antipsychotic overdose presentations were thioridazine, chlorpromazine and haloperidol. Thioridazine accounted for many presentations in the late 1990s, but was then withdrawn from the market in 2009 [Citation13]. Chlorpromazine remained as the only first generation antipsychotic that continued to be seen in overdose, which is likely due to the broader range of conditions for which chlorpromazine continues to be prescribed (on and off label) [Citation6, Citation7].

Our study found that endotracheal intubation was associated with larger reported doses ingested, particularly in single chlorpromazine ingestions (). In single chlorpromazine ingestions, the lowest dose associated with endotracheal intubation was reported to be 1,800 mg. When reported in co-ingestion with other medications, the lowest reported dose for intubation was 500 mg, demonstrating that co-ingested medications causing central nervous system depression were common. There was also an association between larger reported doses ingested and ICU admission, with 1,800 mg being the lowest dose in the chlorpromazine alone group ().

One previous study [Citation4] in chlorpromazine overdoses found that there was a statistically significant association between reported ingested dose and heart rate, but no association with QT interval, QRS duration, or blood pressure. Whilst we did not analyse QT interval data in this series, a previous study found a dose relationship with QT interval in chlorpromazine overdoses [Citation11]. However, significant QT interval prolongation in patients with single chlorpromazine ingestions was rare at 3% [Citation11].

In addition to decreasing numbers of chlorpromazine overdoses occurring after 2007, there was a reduction in the median reported dose ingested. This resulted in fewer ICU admissions and no endotracheal intubations after 2013 (). The reduction in reported dose ingested may be a result of changes in prescribing patterns of chlorpromazine. The reduction in ICU admissions and endotracheal intubations may simply reflect the reduced reported dose ingested, but may also be a result of the increased capacity for many emergency departments to manage patients with reduced GCS.

The median length of stay () following chlorpromazine overdose was slightly longer than for other overdose admissions in the same toxicology unit, in which median length of stay for all overdoses is 16 h [Citation13]. However, the proportion admitted to the ICU (23%) and endotracheally intubated (15%) was much greater compared to all overdoses, of 12.2% and 7.4%, respectively [Citation13]. Our study also found that other complications including delirium (8%), hypotension (4%) and dysrhythmias were much less common.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design and lack of confirmation of ingestion with measurements of serum concentrations. However, previous studies [Citation14–16] have demonstrated patient reliability on amounts ingested in overdose with careful history taking. Despite this, we were unable to determine the reported dose ingested in 29 cases. The impact of reported alcohol co-ingestion is also a limitation in studies of sedating drugs, particularly when reported alcohol co-ingestion is usually over a duration of hours, rather than as a single ingestion. In these series, we considered a single acute ingestion of 10 standard drinks within 2 h as likely to have a significant effect on level of consciousness, and was therefore considered a co-ingestant. In the majority of cases, the patients had less than four standard drinks around the time of the chlorpromazine ingestion, without significant clinical effects. In these cases, alcohol was not considered a co-ingestant. It was also difficult to assess synergistic effects between alcohol and chlorpromazine, or between other sedatives and chlorpromazine, so we only considered chlorpromazine alone and chlorpromazine with any co-ingestant.

The decision to admit to an ICU or endotracheally intubate a patient is based on clinical need, and can also be clinician dependant to some extent. However, we believe our findings reflect similar practice in most units over time in regards to the decision to intubate. Reported dose ingested may also have influenced the decision to refer and admit to the ICU and slightly biased our results.

Conclusions

We found that the most common effect of chlorpromazine overdose was central nervous system depression. Consequently, about one quarter of chlorpromazine overdose admissions required ICU admission and 15% of patients were endotracheally intubated. There was a significant association between reported dose ingested and requirement for intubation. With the reported dose ingested declining after 2013, there was a concurrent decrease in the number of cases admitted to the ICU. Hypotension and delirium were uncommon, and dysrhythmias did not occur.

Authors’ contributions

GI and IB designed the study; collected data; analysed the data; contributed to content and discussion. GI is guarantor of the paper. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, IB, upon reasonable request

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Shane Jenkins for data extraction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- López-Muñoz F, Alamo C, Cuenca E, et al. History of the discovery and clinical introduction of chlorpromazine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17(3):113–135. doi:10.1080/10401230591002002.

- Hoehns JD, Stanford RH, Geraets DR, et al. Torsades de pointes associated with chlorpromazine: case report and review of associated ventricular arrhythmias. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(7):871–883. doi:10.1592/phco.21.9.871.34565.

- Addy JA. Dopamine not effective for treatment of hypotension in chlorpromazine overdose: first case report. J Emerg Nurs. 1995;21(2):99–101. doi:10.1016/s0099-1767(05)80006-6.

- Strachan EM, Kelly CA, Bateman DN. Electrocardiogram and cardiovascular changes in thioridazine and chlorpromazine poisoning. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60(8):541–545. doi:10.1007/s00228-004-0811-7.

- Russell SA, Hennes HM, Herson KJ, et al. Upper airway compromise in acute chlorpromazine ingestion. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(5):467–468. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90154-0.

- Ruiz Yanzi MA, Goicochea MT, Yorio F, et al. Intravenous chlorpromazine as potentially useful treatment for chronic headache disorders. Headache. 2020;60(10):2530–2536. doi:10.1111/head.13976.

- Edinoff AN, Armistead G, Rosa CA, et al. Phenothiazines and their evolving roles in clinical practice: a narrative review. Health Psychol Res. 2022;10(4):38930. doi:10.52965/001c.38930.

- Davis JM, Bartlett E, Termini BA. Overdosage of psychotropic drugs: a review. I. Major and minor tranquilizers. Dis Nerv Syst. 1968;29(3):157–164.

- Buckley NA, Whyte IM, Dawson AH. Cardiotoxicity more common in thioridazine overdose than with other neuroleptics. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33(3):199–204. doi:10.3109/15563659509017984.

- Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, et al. Dose equivalents for antipsychotic drugs: theDDD method. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S90–S94. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv167.

- Berling I, Isbister GK. Prolonged qt risk assessment in antipsychotic overdose using the QT nomogram. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(2):154–164.

- Berling I, Buckley NA, Isbister GK. The antipsychotic story: changes in prescriptions and overdose without better safety. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(1):249–254. doi:10.1111/bcp.12927.

- Buckley NA, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, et al. A prospective cohort study of trends in self-poisoning, Newcastle, Australia, 1987-2012: plus ca change, plus c‘est la meme chose. Med J Aust. 2015;202(8):438–442.

- Friberg LE, Isbister GK, Hackett LP, et al. The population pharmacokinetics of citalopram after deliberate self-poisoning: a bayesian approach. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2005;32(3–4):571–605. doi:10.1007/s10928-005-0022-6.

- Isbister GK, Friberg LE, Hackett LP, et al. Pharmacokinetics of quetiapine in overdose and the effect of activated charcoal. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81(6):821–827. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100193.

- Kumar VV, Isbister GK, Duffull SB. The effect of decontamination procedures on the pharmacodynamics of venlafaxine in overdose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(1):125–132. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03934.x.