Abstract

Evidence of ancient Maya exploitation of salt, other marine resources, settlement, and sea trade is hidden in flooded mangrove landscapes on the cays, mainland, and in shallow offshore locations on the south coast of Belize. This article includes a discussion of the coastal economy from the Middle Preclassic through the Postclassic periods (600 B.C.–A.D. 1500). Data from sites discovered and excavated since 1982 in the coastal area of the Port Honduras and Paynes Creek National Park support a model of coastal reliance on marine resources and tree crops. The need for a regular supply of coastal salt to inland cities may have expanded the market for other marine resources. Obsidian imported from volcanic highlands documents long-distance trade throughout prehistory in the area. The island of Wild Cane Cay expanded its role in long-distance coastal trade after the abandonment of inland cities in southern Belize at the end of the Classic period. Inundation of the region documented from the depths of radiocarbon-dated archaeological deposits below the water table and from a sediment core indicates sea-level rise of at least 1 m that submerged the coastal sites. The waterlogged deposits provided an ideal matrix for preservation of vertebrate material at Wild Cane Cay. The red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) peat below the sea floor in a shallow lagoon preserved wooden buildings.

Introduction

Although coastal archaeological sites present challenges for field research related to their inundation from sea-level rise and erosion, submerged sites can provide valuable information about the past from good preservation of organic material, as well as analogues for modern low-lying areas worldwide subject to global warming and flooding. Some submerged coastal sites preserve food remains, wooden structures, wooden objects, and other organic material that provide a rare record of lifeways (Faught and Smith Citation2021; Purdy Citation1988). Many ancient Maya coastal sites in southern Belize are underwater or flooded under living mangroves, making the sites invisible in the modern landscape, and thus obscuring the extent of coastal Maya settlement and the longevity of Maya sea trade (; McKillop Citation2010, Citation2017a). This article provides an overview of archaeological research since 1982 on the south coast of Belize directed by the author, with assistance from teams of foreign students and volunteers, as well as paid workers from Belize. This synthesis brings together information from various publications on sea trade, diet from plant and animal remains, as well as new data on obsidian and shell middens. The goals and objectives in discussing the research are to highlight the contributions on sea-level rise, sea trade, and the use of marine resources for south coast region of Belize within the context of coastal Maya archaeology, for the broader ancient Maya world, and for coastal research elsewhere.

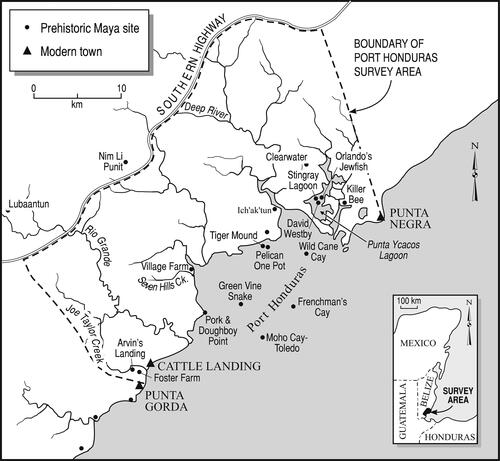

Figure 1. Map of the South Coast of Belize showing places mentioned in the text. Drawing by Mary Lee Eggart, Louisiana State University.

Research objectives developed over time, beginning with fieldwork at Wild Cane Cay in 1982 (). The goals of the Wild Cane Cay fieldwork were to determine the role of the island in ancient Maya sea trade from quantification of obsidian and other trade goods in radiocarbon-dated, stratigraphically excavated deposits, and from excavations of the mounded remains of buildings with coral foundations (McKillop Citation2005a). Mound excavations continued during regional survey from 1991 to 1994 on the coast and cays in the Port Honduras region near Wild Cane Cay in order to discover and date sites and to determine their participation in trade and their relationship to Wild Cane Cay (McKillop Citation1996a, Citation2002, Citation2005a). Regional survey identified many sites (), some of which became the focus of excavations, including Frenchman’s Cay, Ich’ak’tun, and various sites that comprise the Paynes Creek Salt Works. Excavations on Frenchman’s Cay in 1994 and 1996 included stratigraphic excavations in household deposits and transects through coral rock mounds (McKillop et al. Citation2004; McKillop and Winemiller Citation2004). Excavations were carried out at Ich’ak’tun in 1989 (McKillop and Robertson Citation2019) since no other coastal shell middens had been reported in the Maya area apart from a Late Preclassic shell midden on Cancun (Andrews et al. Citation1975) and a Late Classic shell midden on Moho Cay near modern Belize City (McKillop Citation1984). The 1991 discovery of underwater sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon, a large salt-water system in Paynes Creek National Park on the coast opposite Wild Cane Cay, lead to long-term fieldwork to locate, map, date, and excavate the sites. This underwater fieldwork provided new information on Maya salt production, the only-reported ancient Maya wooden architecture, and sea-level rise (; McKillop Citation1995, Citation2002, Citation2005b, Citation2019).

Following an overview of the environmental setting and prehistory of the coastal area and methods developed to survey and excavate in waterlogged and underwater settings, I discuss the contributions and significance of the research. Topics include: (1) sea-level rise in the Late Holocene and its impact on coastal sites in the region, (2) the longevity of Maya sea trade and transportation, and (3) the contribution of salt and other marine resources to Classic Maya diet, economy, and trade.

Environment and prehistory of the south coast of Belize

Red mangroves (Rhizophora mangle) dominate the uninhabited coastal area in southern Belize between the modern communities of Punta Gorda and Punta Negra (). Drier land inland of the red mangroves includes black (Avicennia germinans) and white mangroves (Laguncularia racemosa), broadleaf rainforest, and pine savannah on a coastal plain extending about 15 km inland to the foothills of the Maya Mountains (Wright et al. Citation1959). The main feature of the coastal area is the Port Honduras, a coastal bight into which several navigable rivers flow from the Maya Mountains (). The Port Honduras includes two lines of offshore mangrove cays that formed on limestone ridges on the sea floor. To the south, the Rio Grande provides access to inland areas and the Classic Maya city of Lubaantun. To the north, a large salt-water system called Punta Ycacos Lagoon is bounded by the Deep River to the south and Monkey River to the north and forms Paynes Creek National Park. The coastal area is low-lying land and water.

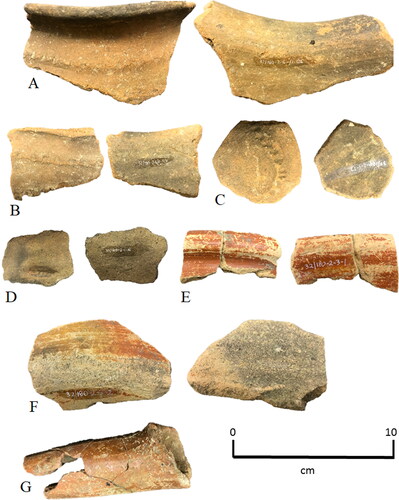

The ancient Maya settled on the south coast of Belize as early as the Middle Preclassic (600–300 BC), with continuous settlement through the Postclassic (AD 900–1500). Pottery from stratigraphic excavations in the shell midden at Ich’ak’tun indicates the site dates from the Middle Preclassic (600–300 BC) to the Late Preclassic (BC–AD 300), making it the earliest known site on the south coast of Belize (McKillop and Robertson Citation2019). The site consists of a shell midden that rises about 2 m above the mangroves at the end of a ridge dominated by cohune palms (Attalea cohune). A 1 × 1 m unit excavated by the author and volunteers in arbitrary 20 cm levels to a depth of 140 cm.

The excavations were assigned ages from associated pottery, which was absent below 100 cm depth (; McKillop and Robertson Citation2019). The earliest known occupation is the Middle Preclassic, identified by Jocote Orange Brown pottery known from the Jenny Creek ceramic complex in the Belize River valley (Gifford Citation1976). The Late Preclassic levels include the 20–40 and 40–60 cm depths at Ich’ak’tun. Seven Late Preclassic sherds were found in the 20–40 cm level, including Sierra Red and Society Hall pottery types, with one Late Preclassic/Transitional Early Classic Laguna Verde pottery sherd from the 40–60 cm depth.

Figure 2. Middle and Late Preclassic Pottery from Ich’ak’tun. (A–D) Jocote Orange Brown, catalog # 32/180-1-6/1-126, -125, -1/1-17, -1/1-16; (E,G) Sierra Red, catalog # 32/180-2-3/1-1, -4/1-107; (F) Society Hall, 32/180-2-3/1-2. Photos by Heather McKillop.

Other early coastal settlements in southern Belize date to the Early Classic (AD 300–900) at Wild Cane Cay and the Paynes Creek Salt Works. Wild Cane Cay began as a small fishing village, as indicated by abundant marine fish bones and endocarps from native palm fruits, other tree crops, and corn in the deepest stratigraphic excavations on the island (McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 4.7). Nearby Pelican Cay site dates to the end of the Early Classic period (McKillop Citation2002, 156–159, Figures 5.5 and 5.6). Several of the sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon have radiocarbon dates with ranges that include the latter part of the Early Classic (McKillop Citation2019, Table 6.2, Figure 6.18).

There was an increase in the number of coastal settlements in the Port Honduras during the Late Classic (AD 600–800) and continuing through the Terminal Classic (AD 800–900; McKillop Citation2002, 154–163). Coastal sites include Pork and Doughboy Point and Village Farm on the mainland. In addition to Wild Cane Cay and Pelican Site, the ancient Maya settled other islands during the Late Classic, including Frenchman’s Cay, Green Vine Snake, and Tiger Mound (). Most of the salt works in Punta Ycacos Lagoon were in operation at that time, mirroring an increase in demand for salt at inland communities in southern Belize, notably at Lubaantun, Nim Li Punit, and Pusilha (McKillop Citation2019).

The abandonment of inland communities at the end of the Classic period in southern Belize did not occur on the coast. Settlement continued on island sites including Wild Cane Cay, Frenchman’s Cay, and Green Vine Snake, all of which have mounds formed by coral rock foundations for perishable structures of pole and thatch built in the Postclassic (McKillop Citation2002, 162–163, Figure 5.10, 2005b; McKillop et al. Citation2004). Production at the Paynes Creek Salt Works may have continued into the Postclassic, since there are several sites with radiocarbon date ranges extending beyond the Classic period (McKillop Citation2019). Certainly, the Postclassic coastal Maya needed salt.

Pirates and missionaries encountered Maya people living on the south coast of Belize in the late seventeenth century, with later accounts of logging by the British, and settlement by Garifuna, US Confederates, and East Indians (Humphries Citation1961; McKillop Citation2005b, 195–196). By 1800, logwood and mahogany were being cut up the rivers in the Port Honduras, although the first land grants in the area were not until 1837 (Humphries Citation1961, 15, 24). Garifuna from Roatan Island in Honduras settled Punta Gorda by 1802. Settlement expanded north at Cattle Landing north of Punta Gorda after 1865, with an influx of American Confederates who brought East Indians as indentured servants. By the mid-nineteenth century, there was a working sugar mill at Seven Hills Creek. Subsistence fishing families lived on the coast and cays of the Port Honduras, including Wild Cane Cay, Village Farm, and other locations identified by historic artifacts (McKillop Citation2005a, 196). By the late twentieth century, the coast and cays were virtually unoccupied.

Discovery of inundated terrestrial sites along the south coast of Belize

Most of the archaeological fieldwork on the south coast of Belize included survey and excavation below the water table or underwater in settings that are common elsewhere along the Yucatan coast but are not the focus of archaeological survey or excavation. Outside of the Maya area, inundated and flooded terrestrial sites have received more attention by archaeologists, notably in England, in Florida and elsewhere (Faught and Smith Citation2021; Purdy Citation1988). The flooded coasts of the Maya area have hidden many Classic period and earlier sites underwater or in mangroves, limiting interpretations of the coastal Maya. The inundated sites on the south coast of Belize are “invisible” in the modern landscape (McKillop Citation2002, Citation2005a).

Archaeological survey and excavation directed by the author documented over 100 ancient Maya sites in a modern landscape virtually devoid of human settlement (, ). Submerged archaeological deposits were discovered in the area in 1982 at Wild Cane Cay. Midden deposits on Wild Cane Cay were excavated at the site to 2.2 m depth. At that time, the water table was 40 cm below the ground surface. Systematic shovel testing in the water and mangroves around Wild Cane Cay in 1989 and 1990 investigated if the artifacts visible on the sea floor had eroded from the shore or if they were in situ evidence of a submerged site (McKillop Citation2002, 150–154, Figures 5.2–5.6). The 172 shovel tests were excavated by arbitrary 20 cm levels to a maximum depth of 1 m and a maximum distance of 50 m from the shore (; McKillop Citation2002, Figure 5.4). Continuous archaeological deposits to depths of 1 m below the sea floor in water ranging in depths from 40 cm to 1 m indicated submergence of a large part of the site and that it was much larger in area in antiquity (McKillop Citation2002, Figure 5.6).

Table 1. Evidence for sea-level rise at sites on the coast, cays, and underwater in Southern Belize.

The discovery of the inundated land at Wild Cane Cay suggested that there were additional sites in the coastal region submerged by sea-level rise. From 1990 to 1994, regional survey on the coast, cays, and shallow water included pedestrian survey, boat survey, shovel-testing, and field-checking of locations on air photos with distinctive vegetation among the mangroves or open areas (; McKillop Citation2002, 154–170). Pork and Doughboy Point, Frenchman’s Cay, and Wild Cane Cay have artifacts visible in shallow water. Green Vine Snake site was visible in the mangroves by distinctive madre cacao (Gliricidia sepium), a dry-land tree species that grows on the mounded remains of coral rock building foundations. Pelican Cay was discovered by shovel tests on a mangrove island with no evidence of a site on the ground surface. Shovel tests revealed a site buried under 40 cm of mangrove peat. Tiger Mound site was located in an open area with an earthen mound on another mangrove island. Boat survey in Punta Ycacos Lagoon consisted of looking over the gunwale to search for artifacts on the sea floor. Submerged sites without any dry land component were discovered (McKillop Citation1995). The first underwater site in Punta Ycacos Lagoon discovered and excavated was the Stingray Lagoon Site, located 300 m from the nearest shoreline, with the water surface 1.0 m above the sea floor (McKillop Citation1995, Citation2002). A new technique developed in 2005 was used in subsequent field seasons for lagoon survey. A team used Research Flotation Devices (RFDs), swimming shoulder to shoulder, systematically traversing the lagoon and marking posts as well as temporally or cultural diagnostic artifacts with survey flags for later mapping. Boat, pedestrian, and RFD survey yielded 110 submerged sites and two sites with earth mounds in the mangrove flats in 10 km2 in Punta Ycacos Lagoon (McKillop Citation2019; Watson and McKillop Citation2019).

Reconstructing the ancient coastal landscape

The discovery of submerged archaeological sites on the coast, cays, and underwater in the Port Honduras and Punta Ycacos Lagoon indicates there was coastal settlement in antiquity from the Middle Preclassic through the Postclassic periods (600 BC–AD 1500), that sea-level had risen and inundated the sites, that there was more land, and that the ancient landscape included a variety of dry-land species. Radiocarbon dating of submerged deposits at sites provided a gauge of sea-level rise of a meter sea-level rise (; McKillop Citation2002). The recovery of endocarps of native palm fruits and other macrobotanical remains from plants that do not grow in salt water or inundated environments, as well as the presence of submerged sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon indicate the land was drier in antiquity (McKillop Citation1994, Citation1996b, Citation2019).

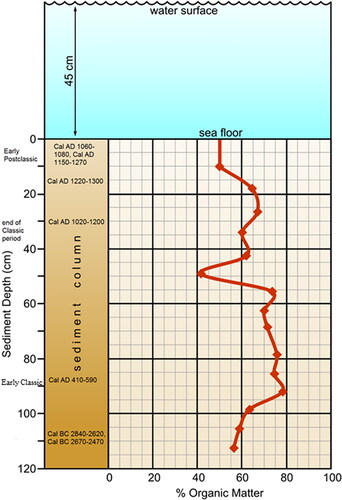

Analysis of a sediment core from Punta Ycacos Lagoon documented sea-level rise in an off-site location between sites 14 (Ka’ak’ Naab’) and 15, unaffected by human activity (McKillop, Sills, and Harrison Citation2010). The core, referred to as the K’ak’ Naab’ core, was cut with an 18” stainless steel knife from a vertical face of a hole dug into the sea floor. A plastic measuring tape was used to measure 10 cm levels from the sea floor, resulting in 15 samples each about 10 cubic cm in dimensions. The depths were later adjusted after the sediment samples were measured on the lab table, with some levels found to be less than 10 cm (see ). A soil probe in Punta Ycacos Lagoon revealed that mangrove peat extended to 4.3 m depth below the sea floor (McKillop 2005b).

Figure 3. Schematic profile of K’ak’Naab’ sediment column, showing percent organic matter, AMS radiocarbon dates, and time periods. Base drawing by Mary Lee Eggart.

Loss-on ignition testing of the marine sediment from each level revealed that the organic content was high, with an average 65% organic matter, similar to the organic content of mangrove peat elsewhere on cays in the barrier reef lagoon between the coast and reef in southern Belize (McKee and Faulkner Citation2000; McKee, Cahoon, and Feller Citation2007; McKillop Citation2002). Microscopic analysis of the sediment indicated it was red mangrove peat composed of fine red mangrove roots. They are stationary near the ground surface when deposited, making them useful for radiocarbon dating mangrove peat deposition.

As a proxy for sea-level rise, mangrove peat develops as red mangroves grow to keep their leaves above water, trapping leaves, sediment, and other detritus among the prop roots and forming a solid, organic deposit. Mangroves can keep pace with gradual sea-level rise, keeping their leaves above water. However, more rapid sea-level rise drowns the red mangroves. As much of 11 meters of red mangrove peat has developed on the limestone shelf between the coast and barrier reef in southern Belize, 40 km offshore during the Holocene (Macintire, Littler, and Littler Citation1995; McKee and Faulkner Citation2000; McKee, Cahoon, and Feller Citation2007; McKillop Citation2002). The water in northern Belize in the inshore lagoon is shallower and lacks the deep peat.

AMS radiocarbon dates on fine mangrove roots from different levels of the K’ak’Naab’ core were used to date sea-level rise in the lagoon (; McKillop, Sills, and Harrison Citation2010). The water surface is 45 cm above the sea floor. The ground surface at the beginning of the Early Classic period around AD 300 was 87 cm below the sea floor (1580 ± 40 years B.P. or Cal AD 410–590). The end of the Classic period settlement is 30 cm below the sea floor. Sea levels rose 57 cm during the Classic period. The uppermost sediment level dates to Cal AD 1060–1080 or Cal AD 1150–1270. Sea-level rise of 30.2 cm continued in the Early Postclassic period (AD 900–1200).

Using Toscano and Macintyre’s (2003) sea-level curve for the Western Atlantic, the rate of sea-level rise during the 660 years of Maya settlement in the Paynes Creek area was 0.087 cm per year. The rate of sea-level rise in the 300 years of the Early Postclassic (AD 900–1200) was 0.01 cm per year—the rate of modern sea-level rise. The lack of mangrove peat after the Early Postclassic indicates that rising seas drowned the mangroves. This process may have been exacerbated by subsidence from the ancient Maya clearing the mangroves to build their salt kitchens and other structures along the ancient shorelines of the lagoon.

The Paynes Creek sea-level data fit with the regional pattern, but also show the ancient Maya’s attempts to counter the deleterious impacts of rising seas (). At Wild Cane Cay, Frenchman’s Cay, and Green Vine Snake, coral foundations that were first constructed in the Terminal Classic elevated wooden buildings above the ground surface and served to mitigate the effects of sea-level rise and flooding the low-lying areas during the Postclassic (McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 6.12). In contrast, the Classic period community on Pelican Cay was abandoned when sea-level rose, since the site is buried under 40 cm of mangrove peat and slightly below the water surface (McKillop Citation2002, Figures 5.8 and 5.9). The Paynes Creek Salt Works were flooded by sea-level rise after they were abandoned, resulting in their modern location underwater in Punta Ycacos Lagoon (McKillop and Sills Citation2021, Citation2022).

Ancient Maya sea trade from the Middle Preclassic through the Postclassic

The coastal Maya of southern Belize were expert mariners who exploited fish and other marine resources by boat and who traveled regularly on the sea and up rivers, as shown by obsidian, non-local pottery, chert, and other trade goods in burials and middens at their settlements (McKillop Citation2005a, Citation2007, Citation2017a, Citation2019; McKillop et al. Citation1988). A canoe, a complete paddle, and fragments of two more paddles were recovered at the Paynes Creek Salt Works preserved in mangrove peat below the seafloor (McKillop Citation2005b, Citation2019; McKillop, Sills, and Cellucci Citation2014). A complete canoe paddle from the K’ak’Naab’ site made from sapodilla wood (Manilkara sp.) was 1.43 meters in length, with a short blade and a long shaft (McKillop 2005b). A smaller paddle was found at Ta’ab Nuk Na, and fragments of canoe paddle blades were recovered from Sites 74 and 83, both made from rosewood (Dalbergia sp.) (McKillop Citation2019, Figures 6.14 and 6.15).

By the Late and Terminal Classic period (AD 600–900), Wild Cane Cay was a major trading port, whose inhabitants continued their reliance on maritime resources, but also participated in coastal canoe trade, as well inland trade via rivers to emerging cities whose residents desired seafood, ritual paraphernalia such as stingray spines, shell for carving, and salt. Salt and salted fish were commodities that were part of the regional marketplace system of coastal and inland communities in southern Belize during the Classic period (McKillop Citation2019, Citation2021; McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018). Wild Cane Cay provided a natural sheltered harbor before the open seas to the north. This site weathered the abandonment of nearby inland cities at the end of the Classic because of the islanders’ role in coastal canoe trade.

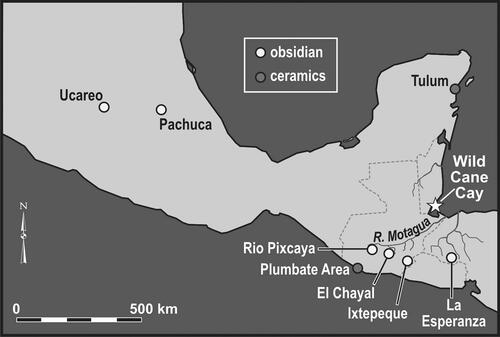

There was canoe trade between coastal and inland communities during the Classic period, as evidenced by inland pottery such as Warrie Red jars, Belize Red bowls, and ocarinas at coastal sites (McKillop Citation2002; McKillop and Sills Citation2021, Citation2022). The coastal Maya also participated in canoe trade along the coast to obtain commodities from greater distances, including obsidian from volcanic highlands of Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico, jadeite from along the Motagua River, chert from northern Belize, and pottery from northern Belize and from Pacific Guatemala (). The coastal Maya on Wild Cane Cay also obtained copper from Honduras and gold from lower Central America (McKillop Citation2005a, 72). In contrast, the inland communities obtained obsidian by overland trade with Maya to the west.

Figure 4. Map of Mesoamerica showing obsidian sources used by the ancient Maya at sites on the south coast of Belize. Drawing by Mary Lee Eggart, Louisiana State University.

Wild Cane Cay expanded its role in coastal canoe trade during the Postclassic, with imported pottery and obsidian in burials associated with buildings in Fighting Conch Mound, indicating far-ranging contacts. Excavations of Fighting Conch mound at Wild Cane Cay revealed six buildings, each with coral rock foundations, finger coral as a subfloor to level the surface, and hard-packed earth floors (McKillop Citation2005a, Figures 6.4 and 6.12). Each building was a platform for a pole and thatch structure, which did not preserve. Burials were dug into the floors or on a floor before a new coral rock foundation was begun. The latter was the case for a young woman buried on her stomach with her legs folded back and her hands and feet placed together as if they had been bound behind her back (McKillop Citation2005a, Figures 6.6 and 6.7). She was buried with a Las Vegas Polychrome pottery vessel imported from Honduras (Joyce Citation2019; McKillop Citation2005a, Figures 6.8 and 6.9). Other burials also were accompanied by Tohil Plumbate, a Silho Fine Orange Vessel (McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 6.19), a Middle Postclassic gouge-incised vessel (McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 6.20), and a Pacmul incised vessel (Tulum Red group; McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 6.28). They were traded from a variety of locations, underscored by the origins of other trade goods associated with burials. Gold foil found in the burial with the fine orange vessel, was a rare import to any Maya site, with likely origins in lower Central America (McKillop Citation2005a, 72). Jadeite beads were traded from the Motagua River outcrops along a coastal trade route from the Caribbean coast of Guatemala (McKillop Citation2005a, Figure 6.23). High-quality jadeite also was used as a tool with a rosewood handle (Dalbergia sp.) dated to the Late to Terminal Classic at Ek Way Nal, one of the largest sites of the Paynes Creek Salt Works (McKillop et al. Citation2019).

Obsidian

As early as the Middle Preclassic, Ich’ak’tun had imported obsidian from the Maya highland outcrop of Ixtepeque (). The 38 obsidian items include 36 flakes and two prismatic blades. Ten of the obsidian flakes each had a bulb of percussion where the flake had been struck off a larger obsidian nodule. One of the flakes and an obsidian blade had cortex, indicating they were chipped off a nodule early in the production process. The dominance of flakes instead of blades is typical of the Middle Preclassic elsewhere in the Maya area (Awe and Healy Citation1994). The excavated obsidian includes 17 from Ixtepeque and one from El Chayal. This pattern differs from the inland community of Ceibal to the west in Guatemala, where El Chayal was the dominant source during the Middle Preclassic (Aoyama Citation2017). However, the Paynes Creek obsidian source use resembles that of Copan, where Ixtepeque obsidian was used from the Preclassic through the Classic periods. The dominance of Ixtepeque source obsidian along the coast began in the Middle Preclassic and continued through the Classic and Postclassic at Wild Cane Cay and other nearby coastal communities.

Obsidian was abundant on the surface of Wild Cane Cay and in the midden deposits (McKillop Citation1989, Citation2005a). The excavated obsidian included 4,243 items, consisting of cores, complete and fragmentary prismatic blades, other artifacts, and manufacturing waste. There was a high density of obsidian, with an increase in the Postclassic period deposits (McKillop Citation1989). Obsidian was not conserved in making blades, as indicated by a study of blade widths compared to other Maya sites, suggesting the Wild Cane Cay Maya had a reliable delivery of obsidian and did not need to hoard or conserve the material in blade production. There were fewer blades than expected from 22 obsidian cores. Using an estimate of 125 blades produced from a typical core in the Maya area (McKillop Citation2005a), a total of 2,720 blades were expected from 22 cores but only 830 blades were recovered (estimating number of blades from the number of proximal blade fragments; McKillop Citation2005a). The possibility that the missing blades were traded regionally to other communities is supported by the lack of obsidian cores from other sites in the coastal area. Compared to the abundance of obsidian from Wild Cane Cay, little obsidian was found at the Paynes Creek Salt Works, but the source use was similar, suggesting the Paynes Creek Maya obtained their obsidian from Wild Cane Cay (McKillop Citation1996a, Citation2019).

A sample of 100 obsidian items from the middens at Wild Cane Cay was selected for chemical characterization at the Lawrence-Berkeley Laboratory (LBL), resulting in 78 Ixtepeque, 18 El Chayal, one Rio Pixcaya (San Martin Jilotepeque), and three Source Z obsidian artifacts (; McKillop et al. Citation1988). Green obsidian blades were visually identified to the Pachuca source north of Mexico City and not submitted for chemical sourcing. The 100 chemically sourced obsidian items were grouped according to visual differences. Additional blades were selected for chemical sourcing based on their visual similarities to the Source Z artifacts and distinctly different visual appearance from the dominant sources of El Chayal and Ixtepeque. Chemical analyses at LBL indicated that three of the blades were assigned to Source Z, one blade was from La Esperanza in Honduras, and one blade was from the Ucareo source in central Mexico. La Esperanza is rare at lowland Maya sites, although it is more common in lower Central America. Source Z is a close match for a river cobble from the Puente Chetunal along the Rio Motagua, suggesting the source location is upriver. Source Z is also found at the site of Quirigua along the Motagua River as well as at least two additional sites.

The diversity of obsidian sources used and abundance of obsidian and other trade goods from various nearby and distant locations supports the interpretation of the island as a trading port along the Caribbean canoe trade route around the Yucatan. Other coastal Maya trading ports include Marco Gonzalez and San Juan on Ambergris Cay (Graham et al. Citation2017; Graham and Pendergast Citation1989; Guderjan and Garber Citation1995), Santa Rita on the mainland in northern Belize (Chase Citation1981), Isla Cerritos and Vista Alegre on the north coast of the Yucatan (Andrews et al. Citation1989; Glover et al. Citation2022), and Xcambó on the west coast of the Yucatán (Sierra Sosa et al. Citation2014).

Marine resources: Their importance to the coastal and inland Maya

Researchers have debated the dietary contribution of seafood for the inland Maya since Lange’s (Citation1971) hypothesis that marine resources provided a viable protein alternative for the Classic inland Maya. Masson (Citation2004) suggested sea catfish (Ariopsis felis) were salted and traded inland during the Terminal Classic (AD 800–900) from Northern River Lagoon site on the north coast of Belize. She found an overabundance of catfish heads in contrast to bodies in the coastal collection. Graham (Citation1994) found cut tuna vertebrae (Thunnus albacares) at coastal sites in central Belize, suggesting to her that the fish were splayed and dried for inland transport.

Vertebrate animals: Marine fish

Abundant and well-preserved fish and other animal bones from waterlogged Late Classic deposits at Wild Cane Cay indicate access to fish and meat from a wide variety of marine, estuarine, riverine, and land environments (McKillop Citation2005a). Marine reef species include parrotfish (Scarus sp.). This is a reef species that is also found on patch reefs in the inshore lagoon near Wild Cane Cay. Estuarine species include barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda), snook (Centropomus undecimalis), jacks (Caranx sp.), snappers (Lutjanus sp.), and groupers (Epinephelus sp.), all common in the coastal area around Wild Cane Cay. Manatee (Trichechus manatus) and green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) bones also were recovered from Classic Maya middens. The former was a major component of a midden from Classic period Moho Cay, an island trading port farther north in the mouth of the Belize River (McKillop Citation1984, Citation1985). Preliminary analysis of the faunal materials indicates that mainland animals include white-tail deer (Odocoileus virginianus), white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), and agouti (Agouti paca). Fishing weights made from notched potsherds were common in Classic middens.

Although bones from fish and other animals did not preserve in the highly acidic mangrove peat matrix of the sites at the Paynes Creek Salt Works, use-wear analysis of chert stone tools from Ek Way Nal and other sites indicated that most of the tools were used to cut fish or meat or to scrape fish or hides (McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018). A minority of the chert tools were used to cut or whittle wood, which was surprising due to the many buildings with sharpened wooden posts (McKillop Citation2016; McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018).

Bone did preserve at Wild Cane Cay, which provides a good comparision with species from the inland city of Lubaantun. Marine fish bones recovered from Lubaantun include bones from several species also identified from Classic period middens at Wild Cane Cay, including snook, jacks, and snappers, which would have been salted for trade so they would not turn rancid (McKillop Citation2019; McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018; Wing Citation1975). Both salt cakes and salted fish were storable commodities that may have served as currency equivalencies (McKillop Citation2021). A minority of the pottery at the salt works was from inland sites, such as unit-stamped Warrie Red jars (McKillop Citation2002, Figures 3.27 and 3.28; McKillop and Sills Citation2021), underscoring exchange between coastal and inland communities. The trade of salt cakes and salted fish supports a model of regional production and distribution of basic resources, instead of long-distance import of salt from the north coast of the Yucatan (McKillop Citation2019; McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018).

Invertebrate animals (mollusks)

Invertebrates (mollusks) contributed to the coastal Maya diet on the south coast of Belize from the Middle Preclassic through the Postclassic. Most species were available near particular settlements, although freshwater jute (Pachychilus sp.), which was a popular dietary mollusk at Wild Cane Cay and Frenchman’s Cay, was transported from nearby rivers. The Preclassic Maya of Ich’ak’tun relied on mangrove oysters (Isognomon alatus and Crassostrea rhizophorae) that were available nearby (). The oyster shells were densely packed and horizontal in the excavations. Large mud conch shells (Melongena sp.) were at the base of the unit in the 100–140 cm undated deposits (that lacked pottery). The shell was counted using the number of identified specimens (NISP) and discarded on site. In the Middle Preclassic deposits (80–100 cm depth), I. alatus was three times as common as C. rhizophorae (). Shell used for decoration included a leafy jewel box clam (Chama sp.) from 60 to 80 cm depth. The presence of 300 pen shells (Atrina sp.) indicates a mangrove flat landscape at the time, as these tiny shells live in mud flats. A single mud conch also suggests a mangrove landscape.

Table 2. Number of shell fragments by species by depth at Ich’ak’tun, Belize.

The Late Preclassic deposits contained I. alatus in the lower levels (40–60 cm depth) and C. rhizophorae in the upper levels (20–40 cm depth). Both are intertidal species associated with a mangrove ecosystem. Fighting conch (Strombus pugilis) occurs in the 20–40 cm level. The habitat of fighting conch extends from intertidal to depth of 2–10 m on sandy and muddy bottoms. These mollusk species are abundant in the Classic and Postclassic middens at Wild Cane Cay (McKillop Citation2005a). One West Indian chank shell (Turbinella angulata) was excavated from the 40–60 cm level. Elsewhere, the ancient Maya used this species to make trumpets, as depicted on a mural from Bonampak showing musicians playing various instruments (Miller Citation1986). Pen shells (80–120 cm) and mud dog whelk (Nassarius sp.; 40–60 cm) are indicators of the former mangrove landscape.

Over 45 invertebrate animal species were abundant in the Classic period middens at Wild Cane Cay (McKillop Citation2005a). Mollusks were collected nearby, reflecting the island setting and in contrast to the mangrove environment of Preclassic Ich’ak’tun. Fighting conch is the most common mollusk species at Wild Cane Cay. A variety of other species were also abundant, including mud conch, queen conch (Aliger gigas), and mangrove oysters (I. alatus and C. rhizophorae). Also recovered were freshwater “jute” shells with their tips broken off, indicating preparation for food.

Shovel testing along two lines forming an X shape across the Frenchman’s Cay site revealed abundant mollusks. Late (AD 600–800) to Terminal (AD 800–900) Classic period middens focused on fighting conch, queen conch, and mud conch, instead of the mangrove oysters, as well as many other species, including nonlocal fresh-water juté for food and West Indian chank shell for trumpets. Identification of the habitats of shells associated with coral rock used to construct platforms for buildings of perishable pole and thatch indicated the coral rock was dredged from near-shore locations (McKillop and Winemiller Citation2004). Submerged shell middens at six of the Paynes Creek sites were dominated by locally available mangrove oyster species (both I. alatus and C. rhizophorae) that grow on red mangrove prop roots along the shores of the lagoon (Feathers and McKillop Citation2018; McKillop Citation2017b).

Salt

Salt cakes and salted fish may have been the marine resources that formed the foundation of coastal-inland trade during the Classic period. Lacking this dietary essential, the inland Maya needed a regular supply of salt. The Paynes Creek Salt Works produced loose salt by boiling brine in pots over a fire inside wooden “salt kitchens,” which were preserved in red mangrove peat below the sea floor at the underwater sites in Punta Ycacos Lagoon (). Briquetage–the salt-making pottery–comprised 90–98% of the artifact assemblages from excavations of salt kitchens (McKillop Citation2019; McKillop and Sills Citation2016), indicating the salt pots were discarded at the salt kitchens. Salt was either traded as loose salt in other containers (Martin Citation2012, Figure 19) or further heated to make solid salt cakes (McKillop Citation2021). Salt cakes were traded regionally from salt kitchens at Sacapulas and other communities beside salt springs in the highlands of Guatemala (Andrews Citation1983; Reina and Monaghan Citation1981). Elsewhere, salt cakes were left in the salt pots for transporting to markets (Yankowski 2010).

Figure 5. Wooden posts with sharpened ends from pole-and-thatch buildings at the Paynes Creek Salt Works, with snorkeling archaeologists in the background. Photo by Heather McKillop.

Some of the salt produced at the Paynes Creek Salt Works was used to dry fish or meat, suggested from use-wear evidence that chert tools were used in processing fish and/or meat (McKillop and Aoyama Citation2018). Other supporting evidence for inland trade of salted fish is that the same species of marine fish excavated at Lubaantun were found in contemporary middens at Wild Cane Cay. Other marine resources were likely added to shipments of salt cakes and salted fish. Inland commodities (Warrie Red water jars, ocarinas, and Zea mays) would have formed useful ballast for empty boats returning to the coast and cays from marketplaces up nearby rivers.

Coastal production and inland distribution of salt was at its height during the Classic period, associated with the rise and demise of inland cities. Salt making was organized as surplus household production at the Paynes Creek Salt Works, with pole and thatch salt kitchens dedicated to boiling brine in pots over fires (McKillop Citation2019, Citation2021; McKillop and Sills Citation2016, Citation2021, Citation2022). This method is practised by historic salt makers in the Maya highlands of Guatemala at Sacapulas, located beside a salt spring (Reina and Monaghan Citation1981). Excavations at the Potok site at the Paynes Creek Salt Works indicated briquetage—the salt-making pottery—composed 98% of the pottery (McKillop and Sills Citation2016). Before the brine-boiling process, the salinity of the lagoon water was increased by pouring it through salty sediment. This process matches modern and historic examples of brine enrichment in order to reduce boiling time and wood fuel needs (McKillop Citation2021; Reina and Monaghan Citation1981; Robinson and McKillop Citation2014). The enrichment process was documented at the Eleanor Betty salt works where a wooden canoe had been re-purposed as a container for brine enrichment (McKillop, Sills, and Cellucci Citation2014). The canoe was supported by stakes, with a clay funnel below to collect the salt-enriched brine. Two sites in the mangrove flats consist of earthen mounds that were the remains of discarded soil from the brine-enrichment process (Watson and McKillop Citation2019).

Further evidence of surplus household production is based on spatial patterning of artifacts individually mapped on the sea floor that are associated with radiocarbon dated wooden buildings. The construction sequence of the 10 pole and thatch buildings was determined by radiocarbon dating a post from each building at the submerged site of Ek Way Nal and Ta’ab Nuk Na (McKillop and Sills Citation2021, Citation2022). The spatial patterning of artifacts embedded in the sea floor indicated the salt workers lived and worked in separate buildings from the end of the Early Classic through the Late and Terminal Classic.

Tree-cropping as a specialized adaption to coastal fishing communities

Tree-cropping along with a diet rich in marine resources, may have been a viable coastal alternative to the inland reliance on corn farming. There is a long tradition of dietary reliance on marine resources by the ancient Maya on the south coast of Belize from the Middle Preclassic at Ich’ak’tun to the Postclassic at Wild Cane Cay and Frenchman’s Cay. Waterlogged archaeological deposits preserved plant food remains on Wild Cane Cay, Frenchman’s Cay, Pelican Cay, and the Paynes Creek Salt Works, indicating tree-cropping was widespread in the coastal region during the Classic and Postclassic periods (McKillop Citation1994, Citation1996b, Citation2019). A separate farming tradition developed at inland communities in southern Belize, beginning with Uxbenka in the Late Preclassic (Prufer et al. Citation2011). Excavations in caves in the Maya Mountains indicate earlier Paleoindian and Archaic people exploited wild resources (Prufer et al. Citation2017).

Tree-cropping was a good strategy on small islands with limited land for farming. About 45 kg of archaeobotanical material was recovered from Late Classic Wild Cane Cay. In rank order using the ubiquity measure, the most common plant foods were fruits from the native palms cohune (Attalea cohune) and coyol (Acrocomia acuealata) as well as other tree fruits, including crabbo/nance (Byrsonima crassifolia) and mamey apple (Pouteria mammosum). These were followed by the native palm fruit poknoboy (Bactris major), corn (Zea mays), and hogplum (Spondias sp.). In addition, avocado (Persea americana) and fig (Ficus sp.) wood was identified, suggesting the fruits from the trees also were consumed (McKillop Citation1994, ). Calabash rinds (Crescentia cujete) were common. They were probably used as containers, although the pulp from this gourd has medicinal uses and the seeds are edible.

The same repertoire of plant food remains typical of Classic period Wild Cane Cay was found at the Paynes Creek Salt Works (McKillop Citation2019; McKillop and Sills Citation2016). The material includes cohune and coyol palm fruits, mamey apple, and hogplum. Partial calabash bowls were found at several sites as well, including a fragment radiocarbon dated to the Late Classic from the Stingray Lagoon site (McKillop Citation2019). Calabash bowls may have been used to add brine from storage jars to the brine-boiling vessels on the fire, as at Sacapulas (Reina and Monaghan Citation1981).

The 10-acre community of Wild Cane Cay continued their subsistence on marine resources and tree cropping, although the evidence is somewhat scant since the Postclassic period middens are not permanently waterlogged like the deeper Classic period deposits. Using ubiquity as an index of relative abundance, cohune palm fruits were the most abundant plant food, followed in order by coyol palm fruits, poknoboy, and then hogplum and crabbo (McKillop Citation1994, ). Differences from the Classic period include an absence of corn, fewer crabbo seeds, and a lack of mamey apple seeds, which may be due to the less-optimal preservation compared to the deeper, waterlogged deposits of the Classic period middens. Exploitation of edible vertebrate animals and mollusks from marine, estuarine, riverine, and land environments continued in the Postclassic (McKillop Citation2005a).

Conclusions

The modern mangrove landscape of the coast and cays obscures most evidence of earlier settlement, reliance on fishing and tree-crops, and the vibrant canoe travel and trade that characterized the coastal area of southern Belize. Fishing camps and coconut walks were established by the British, Spanish, and other settlers during historic times, with mahogany logging from the early nineteenth through early twentieth centuries, but the coastal area is unsettled in the twenty-first century (McKillop Citation2005a, 195–197). Ancient Maya settlement on the coast of southern Belize endured over two millennia, from the Middle Preclassic (c. 600 BC) through the Postclassic periods. Location on the coastal canoe route around the Yucatan— as well as river access to inland cities—certainly underwrote the coastal economy, particularly for the trading port of Wild Cane Cay. The dietary need for salt, a basic biological necessity that was in limited supply at nearby inland cities in southern Belize during the Classic period, certainly led to the rise and expansion of the Paynes Creek Salt Works during the Classic period. Salt production diminished when inland consumers at nearby inland cities were abandoned at the end of the Classic period.

For over two millennia, the coastal Maya of southern Belize were supported by a focus on tree cropping as well as the rich marine landscape, including fish, manatee, turtle, and mollusks. Other known shell middens are on Cancun (Andrews et al. Citation1975) and Moho Cay in the mouth of the Belize River (McKillop Citation1984, Citation2004). There are more excavated shell middens on the south coast of Belize than anywhere else in the Maya area, including the earliest known Maya shell midden at Ich’ak’tun, Wild Cane Cay, and at several submerged sites at the Paynes Creek Salt Works (Feathers and McKillop Citation2018; McKillop Citation2017b; McKillop, Sills, and Cellucci Citation2014).

Ongoing field research includes excavation of individual wooden buildings and associated artifacts at underwater sites at the Paynes Creek Salt Works to examine the organization of the salt industry (McKillop and Sills Citation2021, Citation2022). Radiocarbon dating individual wooden buildings indicates large sites are multi-component, providing sequence of salt production from the end of the Early Classic to the Early Postclassic. Some of the buildings were residences, whereas others were salt kitchens. Continuing field research will further examine variability in activities inside buildings and in outdoor areas. Radiocarbon dating the red mangrove peat matrix of inundated Classic period buildings at the Paynes Creek Salt Works will clarify the timing of their submergence by rising seas, as sobering reminder for low-lying coastal areas elsewhere in the past and present.

Disclosure statement

This is to acknowledge no financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of the research in this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrews, A. P. 1983. Maya Salt production and trade. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Andrews, A. P., F. Asaro, H. V. Michel, F. W. Stross, and R. P. Cervera. 1989. The obsidian trade at Isla Cerritos, Yucatan, Mexico. Journal of Field Archaeology 16 (3):355–63. doi:10.1179/jfa.1989.16.3.355

- Andrews, E. W. I., M. P. Simmons, E. S. Wing, and V. E. W. Andrews. 1975. Excavations of an early shell midden on Isla Cancun, Quintana Roo, Mexico, 147–97. Middle American Research Institute Publication 31, New Orleans: Tulane University.

- Aoyama, K. 2017. Ancient Maya economy: Lithic production and exchange around Ceibal, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 28 (1):279–303. doi:10.1017/S0956536116000183.

- Awe, J., and P. F. Healy. 1994. Flakes to blades? Middle formative development of obsidian artifacts in the Upper Belize River Valley. Latin American Antiquity 5 (3):193–205. doi:10.2307/971879.

- Chase, D. Z. 1981. The Maya postclassic at Santa Rita Corozal. Archaeology 34:25–33.

- Faught, M. K., and M. F. Smith. 2021. The magnificent seven: Marine submerged precontact sites found by systematic geoarchaeology in the Americas. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 16 (1):86–102. doi:10.1080/15564894.2020.1868632

- Feathers, V., and H. McKillop. 2018. Assessment of the shell midden at the Eleanor Betty Salt Work, Belize. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 15:275–85.

- Gifford, J. C. 1976. Prehistoric pottery analysis and the ceramics of Barton Ramie and the Belize Valley. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 18. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Glover, J. B., D. Rissolo, P. A. Beddows, R. Jaijel, D. Smith, and B. Goodman-Tchernov. 2022. The Proyecto Costa Escondida: Historical ecology and the study of past coastal landscapes in the Maya area. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology : 1–20. doi:10.1080/15564894.2022.2061652.

- Graham, E. A. 1994. The Highlands of the Lowlands: Environment and Archaeology in the Stann Creek District, Belize, Central America. Monographs in World Archaeology 19. Washington, DC: Prehistory Press.

- Graham, E. A., R. Macphail, S. Turner, J. Crowther, J. Stegemann, M. Arroyo-Kalin, L. Duncan, R. Whittet, C. Rosique, and P. Austin. 2017. The Marco Gonzalez Maya site, Ambergris Caye, Belize: Assessing the impact of human activities by examining diachronic processes at the local scale. Quaternary International 437:115–42. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.079

- Graham, E. A., and D. M. Pendergast. 1989. Excavations at the Marco Gonzalez Site, Ambergris Cay, Belize, 1986. Journal of Field Archaeology 16:1–16.

- Guderjan, T. H., and J. F. Garber, eds. 1995. Maya maritime trade, settlement, and populations on Ambergris Caye, Belize. Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos.

- Humphries, R. A. 1961. The diplomatic history of British Honduras, 1638–1901. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Joyce, R. 2019. Honduras in Early Postclassic Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica 30 (1):45–58. doi:10.1017/S0956536118000196.

- Lange, F. W. 1971. Marine resources: A viable subsistence alternative for the Prehistoric Lowland Maya. American Anthropologist 73 (3):619–39. doi:10.1525/aa.1971.73.3.02a00070

- Macintire, I. G., M. M. Littler, and D. S. Littler. 1995. Holocene history of Tobacco Range, Belize, Central America. Atoll Research Bulletin 430. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.430.1

- Masson, M. A. 2004. Faunal exploitation from the preclassic to the postclassic periods at four Maya settlements in northern Belize. In Maya Zooarchaeology: New directions in method and theory, Monograph 51, ed. K. F. Emery, 97–122. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, Los Angeles.

- Martin, S. 2012. Hieroglyphs from the painted pyramid: The epigraphy of Chiik Nahb Structure Sub 1-4, Calakmul, Mexico. In Maya Archaeology 2, ed. C. Golden, S. Houston, and J. Skidmore, 60–81. San Francisco: Precolumbia Mesoweb Press.

- McKee, K., D. R. Cahoon, and I. C. Feller. 2007. Caribbean mangroves adjust to rising sea level through biotic controls on change in soil elevation. Global Ecology and Biogeography 16 (5):545–56. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00317.x

- McKee, K., and P. L. Faulkner. 2000. Mangrove peat analysis and reconstruction of vegetation history at the Pelican Cays, Belize. Atoll Research Bulletin 468: 46–58. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.468.47

- McKillop, H. 1984. Prehistoric Maya Reliance on marine resources: Analysis of a midden from Moho Cay, Belize. Journal of Field Archaeology 11 (1):25–35. doi:10.1179/jfa.1984.11.1.25. doi:10.2307/529338

- McKillop, H. 1985. Prehistoric exploitation of the Manatee in the Maya and circum-Caribbean areas. World Archaeology 16 (3):337–53. doi:10.1080/00438243.1985.9979939.

- McKillop, H. 1989. Coastal Maya Trade: Obsidian densities at Wild Cane Cay, Belize. In Research in Economic Anthropology, Supplement 4, ed. P. McAnany and B. Isaac, 17–56. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- McKillop, H. 1994. Ancient Maya tree-cropping: A viable subsistence alternative for the Island Maya. Ancient Mesoamerica 5 (1):129–40. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001085.

- McKillop, H. 1995. Underwater archaeology, salt production, and coastal Maya trade at Stingray Lagoon, Belize. Latin American Antiquity 6 (3):214–28. doi:10.2307/971673.

- McKillop, H. 1996a. Ancient Maya trading ports and the integration of long-distance and regional economies: Wild Cane Cay in South-Coastal Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica 7 (1):49–62. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001280.

- McKillop, H. 1996b. Prehistoric Maya use of native palms: Archaeobotanical and ethnobiological evidence. In The managed mosaic: Ancient Maya agriculture and resource use, ed. S. L. Fedick, 278–94. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- McKillop, H. 2002. Salt: White Gold of the Ancient Maya. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- McKillop, H. 2004. The classic Maya trading port of Moho Cay. In The ancient Maya of the Belize Valley, ed. J. F. Garber, 257–72. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- McKillop, H. 2005a. In search of Maya sea traders. College Station: Texas A & M University Press.

- McKillop, H. 2005b. Finds in Belize document Late Classic Maya salt making and Canoe Transport. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (15):5630–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408486102.

- McKillop, H. 2007. Ancient mariners on the Belize Coast: Salt, stingrays, and seafood. Belizean Studies 29 (2):15–28.

- McKillop, H. 2010. Ancient Maya Canoe navigation and their implications for classic and postclassic Maya economy and trade. Journal of Caribbean Archaeology, Special Publication 3:93–105.

- McKillop, H. 2016. Underwater Maya. http://underwatermaya.com.

- McKillop, H. 2017a. Early Maya navigation and maritime connections in Mesoamerica. In The sea in history: The medieval world, ed. M. Balard, 701–15. Bogner Regis, England: Boydell and Brewer.

- McKillop, H. 2017b. Diving deeper in Punta Ycacos Lagoon at the Paynes Creek Salt Works, Belize. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 14:279–88.

- McKillop, H. 2019. Maya salt works. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- McKillop, H. 2021. Salt as a commodity or money in the classic Maya economy. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 62:101277. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101277.

- McKillop, H., and K. Aoyama. 2018. Salt and marine products in the Classic Maya economy from use-wear study of stone tools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (43):10948–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.1803639115.

- McKillop, H., G. Harlow, A. Sievert, M. Wiemann, and C. W. Smith. 2019. Demystifying jadeite: Underwater Maya discovery at Ek Way Nal, Belize. Antiquity 93 (368):502–18. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.35.

- McKillop, H., L. Jackson, H. Michel, F. Stross, and F. Asaro. 1988. Chemical source analysis of Maya Obsidian: New perspectives from Wild Cane Cay, Belize. In Archaeometry 88: Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Archaeometry Symposium, ed. R. M. Farquhar, R. G. V. Hancock, and L. A. Pavlish, 239–44. Toronto, Canada: Department of Physics, University of Toronto.

- McKillop, H., A. Magnoni, R. Watson, S. Ascher, B. Tucker, and T. Winemiller. 2004. The coral foundations of Coastal Maya Architecture. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 1:347–58.

- McKillop, H., and R. Robertson. 2019. Ich’ak’tun: An early shell midden on the south coast of Belize. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 16:323–32.

- McKillop, H., and E. C. Sills. 2016. Spatial patterning of salt production and wooden buildings evaluated by underwater excavations at Paynes Creek Salt Work 74. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 13:229–37.

- McKillop, H., and E. C. Sills. 2021. Briquetage and brine: Living and working at the classic Maya Salt Works of Ek Way Nal, Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica :1–23. doi:10.1017/S0956536121000341.

- McKillop, H., and E. C. Sills. 2022. Late Classic Maya Salt Workers’ residence identified underwater at Ta’ab Nuk Na, Belize. Antiquity 96:1232–1250. doi:10.15184/aqy.2022.106

- McKillop, H., E. C. Sills, and V. Cellucci. 2014. The ancient Maya canoe paddle and the canoe from Paynes Creek National Park, Belize. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 11:297–306.

- McKillop, H., E. C. Sills, and J. Harrison. 2010. A Late Holocene record of Caribbean sea-level rise: The K’ak’ Naab’ Underwater Site Sediment Record, Belize. ACUA Underwater Archaeology Proceedings 2010:200–7.

- McKillop, H., and T. Winemiller. 2004. Ancient Maya environment, settlement, and diet: Quantitative and GIS analyses of Mollusca from Frenchman’s Cay. In Maya Zooarchaeology, ed. K. Emery, 57–80. Los Angles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

- Miller, M. 1986. The murals of Bonampak. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Prufer, K. M., C. R. Meredith, A. V. Alsgaard, T. Denehey, and D. J. Kennett. 2017. The Paleoindian chronology of Tzib Te Yux rockshelter in the Rio Blanco valley of Southern Belize. Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 14:321–6.

- Prufer, K. M., H. Moyes, B. J. Culleton, A. Kindon, and D. J. Kennett. 2011. Formation of a complex polity on the eastern periphery of the Maya lowlands. Latin American Antiquity 22 (2):199–223. doi:10.7183/1045-6635.22.2.199

- Purdy, B., ed. 1988. Wet Site Archaeology. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Reina, R. E., and J. Monaghan. 1981. The ways of the Maya: Salt production in Sacapulas, Guatemala. Expedition 23:13–33.

- Robinson, M., and H. McKillop. 2014. Fueling the ancient Maya salt industry. Economic Botany 68 (1):96–108. doi:10.1007/s12231-014-9263-x

- Sierra Sosa, T., A. Cucina, T. D. Price, J. H. Burton, and V. Tiesler. 2014. Maya coastal production, exchange, lifestyle, and population mobility: A view from the port of Xcambó, Yucatán, Mexico. Ancient Mesoamerica 25 (1):221–38. doi:10.1017/S0956536114000133

- Toscano, M. A., and I. G. Macintyre. 2003. Corrected Western Atlantic Sea-level curve for the last 11,000 years based on calibrated 14C dates from Acropora palmata framework and intertidal mangrove peat. Coral Reefs 22 (3):257–70. doi:10.1007/s00338-003-0315-4

- Watson, R., and H. McKillop. 2019. A filtered past: Interpreting salt production and trade models from two remnant brine enrichment mounds at the ancient Maya Paynes Creek Salt Works, Belize. Journal of Field Archaeology 44 (1):40–51. doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1557993.

- Wing, E. S. 1975. Animal remains from Lubaantun. In Lubaantun: A classic Maya realm, Peabody Museum Monograph 2, ed. N. Hammond, 379–83. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Wright, A. C. S., R. H. Romney, R. H. Arbuckle, and V. E. Vial. 1959. Land in British Honduras: Report of the British Honduras Land Use Survey Team. Colonial Research Publication 24. London: Colonial Office.

- Yankowski, A. 2010. Traditional technologies and ancient commodities: An ethnoarchaeological study of salt manufacturing and pottery production in Bohol, Central Philippines. In Salt Archaeology in China, Volume 2: Global comparative perspectives, ed. S. Li and L. von Falkenhausen, 161–81. Beijing: Science Press.