Abstract

The essence of stories of human–environment interactions can be preserved in oral contexts for millennia, creating novel opportunities for humanizing the past. This study examines stories (knowledge-rich narratives) about the ancestral being Ngurunderi, told by Ngarrindjeri peoples of South Australia. Three elements of the Ngurunderi narrative are considered. The first recalls his journey along a 170-km long coastal barrier (Younghusband Peninsula) when this was continuous. The second discusses Ngurunderi’s encounters with what are now islands off the Fleurieu Peninsula, some of which he created, interpreted as memories of when sea level was lower and “islands” were contiguous with the mainland. The third refers to the crossing of a land connection between modern Kangaroo Island and the Fleurieu Peninsula, later submerged to form Backstairs Passage. Using paleogeographic data, the most recent times at which each narrative element could have taken place and observed by people are estimated. This research suggests that: (1) stories about Younghusband Peninsula may be >6700 years cal BP; (2) islands off the Fleurieu Peninsula were created 6800–10,400 cal BP; and (3) submergence of Backstairs Passage occurred 11,000–10,100 cal BP. Narratives are linked to the period of early Holocene sea-level rise, the rapid 8200-cal BP sea-level rise event, and stabilization of sea level 7000–6000 cal BP. These narratives humanize the past and provide information that can be interpreted as both observed coastal and seascape changes as well as past human responses to rising sea level that can inform our future encounters with coastal-landscape change.

Introduction

Understanding the processes involved in Holocene landscape evolution depends largely on dating key sites/strata and inferring details of the events they represent. While this approach can yield robust science-based models of landscape change, they generally say little about the impacts on humans of these changes; such details are invariably topics for speculation. This study takes a contrasting approach, interpreting ancient stories (ancestral narratives) that include landscape descriptions to reconstruct components of that landscape at particular periods, and to show how humans—in their own words—were affected by and interpreted the landscape changes they observed. Building on recent studies which demonstrate that narratives recalling details of memorable landscape changes can in optimal contexts be passed down for thousands of years (Hamacher et al. Citation2023; Hemming, Jones, and Clarke Citation1989; Holdgate, Wagstaff, and Gallagher Citation2011; Nunn Citation2018; Roberts et al. Citation2020, Citation2023), this study explores the possibilities and constraints imposed by Holocene coastal-landscape change on human activities in parts of South Australia.

This research uses a detailed and comparatively well-documented narrative to answer questions about Holocene coastal–island landscape/seascape changes as well as human–environment interactions in South Australia, information that cannot be gleaned from any other source. Comparison between landscape changes recorded in the narratives and those deduced from conventional landscape-history analysis allows insights into the nature and succession of particular events and the antiquity of the stories in which their descriptions are preserved. Most of the events described are attributable to the effects of postglacial sea-level rise, which occurred around Australia between approximately 15,000 and 6000 years ago, and involved a net rise of 125–130 m, reducing the landmass of this already long-inhabited continent by almost a quarter.

The elements of the Ngurunderi narrative on which this paper focuses are described and illustrated in the next section. The ways in which ages are assigned to these elements, specifically the human–environment interactions and encounters they describe, are then explained. There follows a discussion of how ancient narratives (like the Ngurunderi narrative) can inform the understanding of deep-time landscape and seascape changes, and the ways these affected human existence.

Ngurunderi

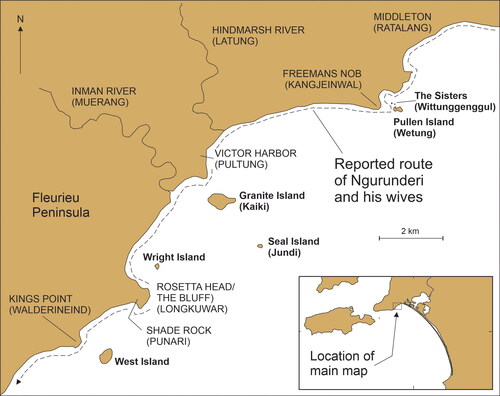

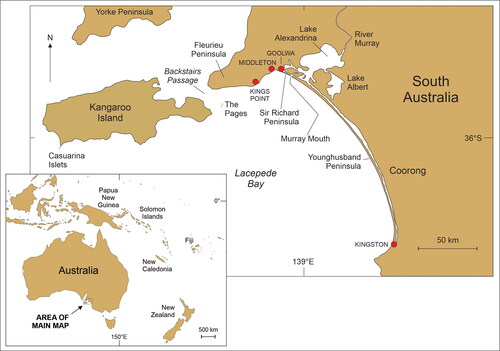

Stories about a man named Ngurunderi (Ngurunduri/Nurunduri/Ooroondorie) are well known among the Indigenous (Aboriginal) peoples of South Australia, especially the Ngarrindjeri. The Ngurunderi narrative is essentially that recalling the journey of its eponymous ancestral being throughout South Australia, commencing in the upper parts of the River Murray (Roberts et al. Citation2023), an element not considered in this study, and then continuing from Lake Albert through the Coorong wetlands, along Younghusband Peninsula and the southern Fleurieu Peninsula, ending in Kangaroo Island (). This study is concerned largely with three particular parts of the narrative, namely Ngurunderi’s journeys along Younghusband Peninsula (from Kingston to Goolwa), that along the southeast coast of Fleurieu Peninsula (from Middleton to Kings Point), and that referring to the crossing of Backstairs Passage, which today separates the western end of Fleurieu Peninsula from Kangaroo Island. While European place names are used in this paper, we also privilege Ngarrindjeri toponyms ().

Figure 1. The study area extends along the coasts of the Coorong, Fleurieu Peninsula and Kangaroo Island (South Australia). Smaller map shows the location of the study area within the Asia-Pacific region.

Table 1. Synonyms and name variants for key people and places in the Ngurunderi narrative.

The oral traditions (and those recently transcribed) that comprise the Ngurunderi narrative are likely to include content from different places and time periods that became incorporated into the accounts of oral storytellers over several thousand years; Aboriginal oral traditions are flexible and stories may vary according to the time and place of telling (Roberts et al. Citation2023). Surviving versions of the narrative are likely to conflate events in the lives of several memorable individuals, maybe only one named Ngurunderi, to create a narrative palimpsest in which details of human encounters and observations of landscape, often over many millennia, have been preserved, a comparable situation to elsewhere in the world (Barber and Barber Citation2004; Cruikshank Citation2007; Taggart Citation2018).

While there are those who argue that such processes invalidate the preservation of empirical details in such stories (Henige Citation2009; Sansom Citation2006), most authorities have adopted more nuanced positions. The decolonizing of (non-Western) “myth” and the ways it was constructed (and misrepresented) are considered foundational to the recognition of the histories they represent as accounts of human pasts (Bacigalupo Citation2013; Echo-Hawk Citation2000; Marker Citation2015). Such invalidation also discounts the opportunities for “knowledge exchange” (or two-way learning) and approaches that explore the complementarity between Indigenous and Western knowledges, as well as their difference, in order to find ways for “Indigenous frameworks” to transform academia (Atalay Citation2020); it is imperative that any consideration of traditional narratives be done with Indigenous peoples.Footnote1 A related challenge has been to overcome the prejudices of researchers to recognize orally-communicated knowledges as information sources that enabled human societies to be sustained for most of the time they have existed—and often remain the most effective way for the future in particular contexts (Fakhriati et al. Citation2023; Sugiyama Citation2021).

In regard to Indigenous Australian stories of coastal-landscape change, a potent argument in favor of their empirical basis is the fact that, when divested of narrative embellishment, such stories tell essentially the same things. This implies that, in optimal contexts, observations of events which occurred millennia earlier may be preserved in such stories (Campbell Citation1967; Hamacher et al. Citation2023; Morphy et al. Citation2020; Nunn and Reid Citation2016; Sharpe and Tunbridge Citation1999). This shows that Indigenous interpretations of geological events often align with more recent retrodictive western-scientific reconstructions of these, underscoring the point that Indigenous people were and are expert observers of the lands they occupied and that Indigenous/traditional narratives can provide valuable insights into the nature and effects of such events in deep time (Masse Citation2007; Piccardi et al. Citation2008; Roberts et al. Citation2023). Independent dating of events such as volcanic eruptions, astronomical alignments, and postglacial sea-level rise show that the observations which seeded some of these stories occurred thousands of years ago (Hamacher Citation2022; Hamacher et al. Citation2023; Nunn Citation2018; Nunn et al. Citation2019; Wilkie, Cahir, and Clark Citation2020).

Indeed, recent scholarship has emphasized the links between archaeology and oral traditions, broadly framed, to discuss issues as varied as the symbolism of settlement design and introduction of exotic macaws in the southwest USA (Bloch Citation2019; Kelley Citation2020), and the archaeological evidence “to support the view that the traditional narratives [of Polynesian peoples] relate to real persons and events” (Kirch Citation2018, 275).

While acknowledging the challenges, especially the unknowables, involved in the interpretations of such ancient stories, it is probable that the surviving stories represent only a small fraction of the range of stories that existed. Most extant details come from men who had opportunities to share them with non-Indigenous (mostly male) listeners who transcribed them. Women’s stories, while once equally numerous, made it through this cultural filter far less commonly, meaning that extant stories foreground masculinity in ways that are unlikely to represent their true diversity, either today or in the pre-contact past (Bell Citation1998). Similarly, in oral societies, there is not a single version of a particular narrative (as is often the case in literate societies) but multiple variants that may each privilege the interests of particular groups or a favored version of particular events. Once such stories start to be written down, there is commonly little interest in recording their diversity which has led to a situation where a single version, arbitrarily chosen, is by default considered the definitive one (Ong Citation1982).

Ngurunderi travels from Lake Albert through the Coorong and along the Younghusband and Sir Richard Peninsulas

The early part of the Ngurunderi narrative, recently been summarized by Roberts et al. (Citation2023), involves him traveling down the River Murray valley in pursuit of a giant fish, the Murray Cod (pondi). The part relevant to this study begins when Ngurunderi smells fish (tukeri), forbidden to women, being cooked by his two wives at Kurelpang on the eastern shore of Lake Albert (see ). Knowing Ngurunderi was approaching and would be angry, the two women make a reed-raft and pole across the lake to evade him. They then head southeast into the Coorong, pursued at some distance by Ngurunderi (Berndt Citation1940; Clarke Citation1995; Woods Citation1879).

Close to Kingston, near Blackford according to Albert Karloan (Berndt Citation1940, 174), Ngurunderi encountered the sorcerer Parampari and the two quarreled, culminating in Ngurunderi slaying him. He placed the body on a blazing pyre at The Granites, a conspicuous outcrop of granitic rocks on the beach of Younghusband Peninsula 20 km north of Kingston (Dillenburg et al. Citation2020), before walking briskly north along its entire 170-km length at a time when it appears to have been a continuous barrier island extending to the River Murray Mouth, much as today.

Different versions of the Ngurunderi narrative have him collecting water and food in various places and spending some time at what may have been his home at Ngurunderwerkngali on the landward side of Younghusband Peninsula (Wilson Citation2017, 64). For example, at Wunjurem, Ngurunderi dug a hole (soak) in the sand to find fresh water for drinking; then, “as his head touched the sand, the concave depression it made … was transformed to rock” (Berndt Citation1940, 176). Eventually, deciding to renew his pursuit of his wives, he walked northwest across the mouth of the River Murray and along the Sir Richard Peninsula to Goolwa, at the eastern extremity of Fleurieu Peninsula.

Ngurunderi and the formation of islands off the southeast Fleurieu Peninsula

Off the southeast coast of Fleurieu Peninsula lie several islands, the largest of which all feature in the Ngurunderi narrative, typically as places he created or visited. In both of these meanings, it is likely that at the time/s of Ngurunderi, what are now nearshore islands were attached to the mainland. The fact that they are today islands therefore means that, for the Ngurunderi narrative to appear factual to more recent audiences, these islands were either “created” by Ngurunderi at the time of his visit or “walked” to by him, perhaps as a giant capable of over-water strides, a detail featuring in some accounts. For example, one of the earliest written reports states that wherever Ngurunderi went “he spread terror among the people, who were dwarfs compared with him” (Meyer Citation1846, 205).

This is a common type of narrative motif in stories that have been passed down across sometimes hundreds of generations from times when (coastal) landscapes were different from those of today and people walked across places that were later submerged. It may represent an example of the rationalization syndrome, a post-observation rationalization of events (Barber and Barber Citation2004). It is common in coastal parts of northwest Europe where numerous stories interpreted as submergence memories involve giant beings able to effortlessly stride across what are today wide water/ocean gaps. For example in Australia, this explanation is explicit in Malgana (Shark Bay) stories about when their giant ancestors walked between Denham (on the mainland) and Dirk Hartog Island (Wirruwana); clay pans (birridas) in the landscape are interpreted as their footprints (Nunn et al. Citation2022). The reasoning is that, as oral stories about a time when an ocean gap was dry land become more strained (less plausible) in their retelling, storytellers will often introduce rationalizing elements to convince their audiences of the story’s foundation in truth. Thus, Ngurunderi must have been a giant if he walked to what is now a nearshore island or he must have been endowed with superhuman powers to have magically “created” islands if they did not exist when he was there but do so today.

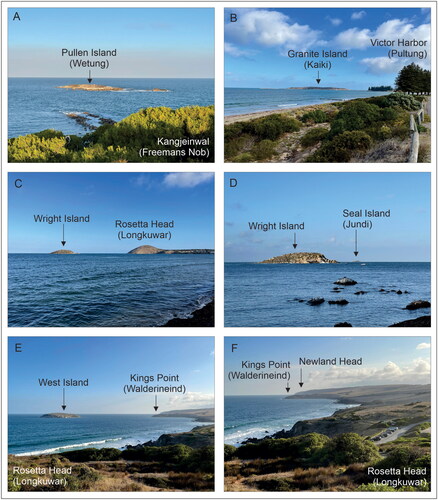

shows the southeast coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula between Middleton and Kings Point, and includes all the nearshore islands mentioned in one or other extant versions of the Ngurunderi narrative. Also shown is the route followed by Ngurunderi in pursuit of his two wives.

When Ngurunderi arrived at Freemans Nob, “he threw two small nets, called witti, into the sea, and immediately two small rocky islands arose, which ever since have been called Wittungenggul” (Woods Citation1879, 60). These islands are likely to be what are today called The Sisters although no known version of the narrative states this. Later, perhaps having caught enough fish and “having no further use of his fishing net, he walked across to Wetung (Pullen Island) and threw it on the first rock” (Berndt Citation1940, 178). It is not possible to walk to Pullen Island today, so it is inferred that this part of the narrative, involving the creation of The Sisters and the walking to Pullen, occurred when the sea level was lower and all three islands were contiguous with the mainland. It is also worth noting that this area is the only location known from surviving stories where an earlier ancestral being (Jekejere) is mentioned as having been in the area before Ngurunderi, the latter praising him for having created the fishing grounds there (Berndt Citation1940, 178f; Tindale Citation1937, 115–6). Tindale (Citation1937) recorded a song (19) from his main Tangane (Ngarrindjeri) informant, Milerum, which went as follows.

'Thuŋarei’nar 'nari’meiŋg 'parlpa’wulinar/eraijaŋanamp mi’niŋ’gund

n‘deitj’undal/'thuŋa’reinar 'nari’meiŋg 'parlpa’wulinar/ha! a! 'eik:'einin

ŋere’gei 'njunum’puduŋg/'ŋeilin 'naŋana’bin 'jeke’jeril 'jaragara’ŋeil.

In translation—“Words [of Ngurunderi] shore edge completed/‘hill’ remain always/words shore edge completed/‘early start of day’ [earliest dawn] wonderful work/for us did it Jekejere [man’s name] completed it.”

Three other ancestral beings in this area (Nurelli, Korna, Thukabi) may either have been synonymous with Ngurunderi or represent distinct ancestors (Clarke Citation1995). This may be a hint of the multi-generational character of the Ngurunderi narrative that was known to earlier storytellers (see above).

As Ngurunderi was leaving Freemans Nob, he heard his wives at (in the direction of?) Kings Point and said “Wul ‘thlurnaŋ” (Down there those two) and quickly walked to Victor Harbor where no islands existed at the time (Berndt Citation1940). In play, Ngurunderi threw his spear out to sea and as it hit the water, he commanded “Pruk’ul ru’ind” (Rise up earth) and Granite Island appeared. Then he walked to the top of this newly created island and threw another (wooden) spear (jundi) out to sea, repeating the same words and so creating Seal Island. Later, having crossed the mouth of the Inman River, he threw a (reed) spear (kaiki) into the ocean, creating Wright Island (Berndt Citation1940, 179).

Ngurunderi then climbed Rosetta Head (The Bluff) where he spent “much time” before walking to Kings Point and found evidence his wives had been there recently. From the tip of Kings Point, Ngurunderi threw a (reed) spear into the ocean to create West Island and then, seeing his wives in the distance, he continued to follow them (Berndt Citation1940, 180). All islands mentioned in this subsection are pictured in .

Ngurunderi and the submergence of Backstairs Passage

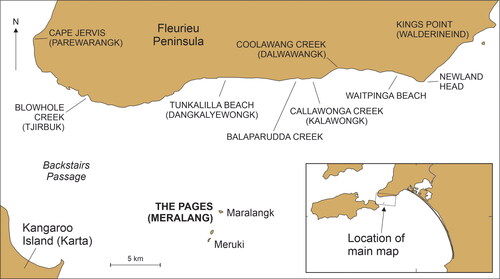

Ngurunderi followed his wives around Newland Head, past Waitpinga, Callawonga, Balaparudda, and Tunkalilla (). When the two women reached Blowhole Creek, they could see Kangaroo Island which “at that time … was almost connected with the mainland, and it was possible for people to walk across” (Berndt Citation1940, 181), perhaps through a combination of “walking and wading” (Campbell Citation1967, 477).

More detail is given by Ngarrindjeri author David Unaipon:

At the time of the story the Island [Kangaroo Island] was connected with the mainland but during a severe southerly storm the sea would cover the connecting strip of land. (In Gale Citation2000, Appendix 8.3, 118)

Such may have been the case on the afternoon when Ngurunderi’s wives reached Blowhole Creek for they spent the rest of that day gathering honey. But as Unaipon notes, another reason for their delay was a “keeper” of the land bridge named Khowwallie (Knowallie), the Blue Crane, and how “no one would attempt to cross without his permission” (in Gale Citation2000, Appendix 8.3, 118). So, the following morning, the two women, having obtained this permission:

began laughing and chatting, anticipating the joy and pleasure and happiness that awaited them when they arrived upon the Spirit Land [Kangaroo Island], but most of all they would be free from the law [Ngurunderi] they were trying to escape. (In Gale Citation2000, Appendix 8.3, 118)

They began to walk across (Backstairs Passage) carrying “mats (for fish) and nets (to carry food in)” (Berndt Citation1940, 181).

When Ngurunderi reached a vantage point above Blowhole Creek, he could see his wives crossing to Kangaroo Island. When they were halfway across (what is today) Backstairs Passage, he

called out in a voice of thunder, saying: “Pink’ul’uŋ’urn ‘praŋukurn” (Fall waters-you). Immediately the waters (sea) began to come in from the west, wave upon wave, driving the two women from their course. So rough, so strong, were the tempestuous waves, that the women tried to turn their faces towards the mainland. At last, fighting against the waves no more, they were carried to the open sea, taking with them their net baskets. (Berndt Citation1940, 181)

Ngurunderi’s wives and their net baskets were transformed into The Pages (islands); the largest of the three is said to be the older sister and her basket, the middle island is the younger sister, the smallest the basket she had been carrying. Writing in the 1920s, Unaipon notes that “many were the pilgrimages taken by the aborigines in days-gone by to see these stones [The Pages] and view and contemplate the way of the Great Teacher, Narroondarie [Ngurunderi]” (Gale Citation2000, Appendix 8.3, 119).

Similar versions of this part of the narrative are told in its earliest written renditions. For example, Cawthorne (Citation1926 (for 1844)) recounts how the wives of Ngurunderi (Ooroondovil) “were drowned and turned into islands” (72). Meyer (Citation1846) reported that Ngurunderi (Nurunduri) became tired of pursuing his wives so “he ordered the sea to flow and drown them … they were transformed into rocks” (205). Taplin (Citation1879) states that, after “his wives forsook him,” Ngurunderi (Nurunderi) “called upon the sea to overflow and drown them, and it obeyed” (38).

While most accounts name Blowhole Creek (Tjirbuk) as the place from which Ngurunderi’s wives started to walk across to Kangaroo Island, there are two other possibilities. In one, the wives of Ngurunderi flee from him “in terror, until they reached Cape Jervis” (see ), whence they “hurry across the land bridge to what is now Kangaroo Island” (Bell Citation1998, 92). In the other, told by Ramindjeri informant Reuben Walker to Tindale (quoted in Draper Citation2015, 239), the summoning of the waves to drown Backstairs Passage takes place earlier when Ngurunderi stood atop Granite Island (see ) and noticed his wives about to land on Kangaroo Island.

After the two women drowned, Backstairs Passage remained covered with ocean, requiring Ngurunderi to later dive and swim to Kangaroo Island (Berndt Citation1940; Flood Citation1995; Woods Citation1879). In the account of Reuben Walker (in Draper Citation2015, 239), Ngurunderi passed Waitpinga before diving off the cliff into the ocean to reach Kangaroo Island. In a detail which may have been inspired by the story about the parting of the Red Sea in the Christian Bible, Unaipon appears alone in suggesting that after his wives had been turned to stone, Ngurunderi commanded the waters to recede, allowing him to walk to Kangaroo Island (in Gale Citation2000, Appendix 8.3, 119).

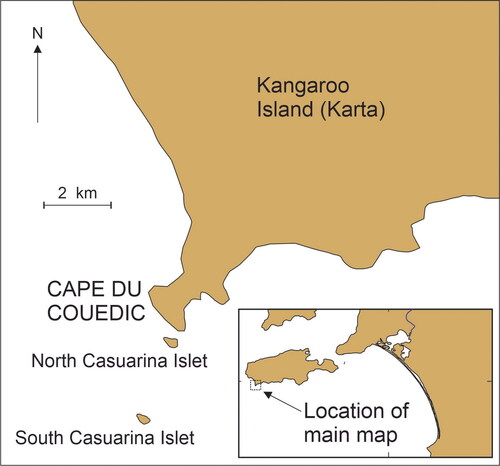

Ngurunderi on Kangaroo Island

Once Ngurunderi reached Kangaroo Island and rested, he traveled west until he reached its southwest point near Cape du Couedic where he threw out his “last-remaining spear” to create a group of nearshore islands (Berndt, Berndt, and Stanton Citation1993, 226), known as the Casuarina Islets or The Brothers (), whereupon “he jumped into the sea, dived, and finally reappeared as a star in the heavens” (Tindale and Maegraith Citation1931, 286). The formation of the Casuarina Islets by Ngurunderi is also alluded to by Spender, one of Tindale’s Aboriginal informants, although the islands are not identified (quoted in Clarke Citation1995, 151). It is conceivable that the departure of Ngurunderi from Kangaroo Island is (or was informed by) a memory of this island’s apparent abandonment that made it a “mystery” for later visitors (Draper Citation2015; Lampert Citation1981).

Determining ages for elements of the Ngurunderi narrative

Despite the Ngurunderi narrative being a composite narrative, comprising elements from different time periods involving multiple individuals (who may be telling stories for different purposes), it is possible to identify elements that appear common and consistent in several extant versions. Three elements, discussed in separate subsections below, refer respectively to the continuous nature of Younghusband Peninsula, the formation of (small) islands off mainland coasts, and the formation/inundation of Backstairs Passage. Geochronological research provides ages (or age ranges) for these events which can thus be considered as proxy ages for associated elements of the Ngurunderi narrative.

Continuity of Younghusband Peninsula

Together with Sir Richard Peninsula, the dune-covered core of Younghusband Peninsula comprises an uncommonly long coastal barrier system formed here after the postglacial sea level reached its present level around 7000 years cal BP (Bourman, Harvey, et al. Citation2018; Bourman, Murray-Wallace, et al. Citation2018; Harvey, Bourman, and James Citation2006; Short and Hesp Citation1984). In most versions of the Ngurunderi narrative, he is said to have walked the entire length, around 170 km, of Younghusband Peninsula from around its southern terminus near Kingston to the River Murray Mouth (see ). Several versions of the narrative refer to the speed with which Ngurunderi covered this great distance, possibly a narrative proxy for the continuity and comparative monotony of the Peninsula.

Although other interpretations are possible, all available evidence suggests that when Ngurunderi walked the length of Younghusband Peninsula, it was a continuous barrier. So, the earliest age of continuous barrier formation provides a maximum age for this element of the Ngurunderi narrative. Ages from the core beach sequence within Younghusband Peninsula include dates of ∼6000 BP from Baynton Bluff (Short and Hesp Citation1984) that are in broad agreement with Aboriginal midden ages of 5910 ± 70 BP from Hack Point and 5545 ± 140 BP from Cantara (Harvey, Bourman, and James Citation2006; Luebbers Citation1981, Citation1982). Yet midden shellfish analysis suggests periodic flushing of the Coorong lagoon with seawater occurred around 6000 years ago, implying that the “Younghusband Peninsula was not a continuous barrier early in its history” (Harvey, Bourman, and James Citation2006, 43), a view supported by the notion that the early stages of barrier evolution here after sea level stabilized about 6000 years ago may have been marked by the formation of “isolated barrier islands” that subsequently coalesced (Bourman, Murray-Wallace, et al. Citation2018, 74; Harvey Citation2006).

An alternative interpretation, important to the present study, is that “the barrier was initially formed … as a single island extending from the Murray mouth to Kingston” (Dillenburg et al. Citation2020, 8), meaning that Ngurunderi could have walked its length from The Granites to the Murray mouth somewhat earlier. The latter condition may have been achieved around 6700 cal BP, providing a possible maximum age for this element of the Ngurunderi narrative. Since sea level at this time was at least 1.23 m (at The Granites) higher than today, if Ngurunderi did then walk briskly along the length of Younghusband Peninsula it would have been much narrower; the briskness may allude to avoiding seawater incursions at high tide.

A third possibility assumes that the stories about Ngurunderi walking the length of Younghusband Peninsula were close in age to those recalling his role in the creation of Backstairs Passage more than 10,000 years ago (see below), so it may be that the former stories refer to an earlier time, more than 7000 years ago when sea level was lower and Ngurunderi walked the length of a proto-barrier, now covered by ocean, between Kingston and Goolwa.

In all known versions of the Ngurunderi narrative, the River Murray Mouth is stated as breaking the continuity of the sedimentary barrier comprising Younghusband and Sir Richard Peninsulas, just as it does today. Details of how Ngurunderi and his wives (whose footprints he found on the northern side of the river mouth) crossed the Murray Mouth are vague in most versions of the narrative. For example, one recalls Ngurunderi merely “crossing the mouth of the lakes (Murray Mouth)” (Berndt Citation1940, 176). But in another version, unquestionably that of David Unaipon (Gale Citation2000), it is stated that Ngurunderi “prayed to make it possible for him to walk across,” a prayer that was answered when a bridge then formed across the river (Smith Citation1930, 327). It is possible that the existence of a “bridge,” implicitly temporary, recalls a narrator’s experience of one of the short-lived closures of the Murray Mouth (in its original pre-European condition), as happened when it periodically became blocked by a plug of inner-shelf marine sediments that was not easily dislodged by river flows. The sole pre-European inference of mouth closure within the past 6000 years is thought to have occurred around 3500 years ago during a period of conspicuous aridity and reduced river flow (Bourman, Harvey, et al. Citation2018; Cann, Bourman, and Barnett Citation2000; Murray-Wallace et al. Citation2010) and it may be that the bridge element of the story dates from this time. Yet alternatively, just as argued above, it may be that the “bridge” was a later rationalization of the time when Ngurunderi walked along a proto-barrier that existed before the modern Younghusband Peninsula took shape.

Formation of nearshore islands

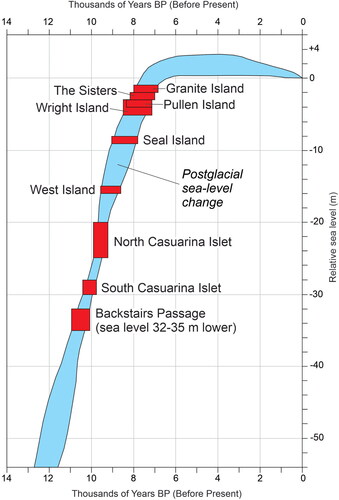

Off the southeast coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula lie six islands (see ) that are stated in various versions of the Ngurunderi narrative to have been created or visited by him. Off the southwest tip of Kangaroo Island, two islands (see ) are also said to have been created by Ngurunderi. Creation of islands is interpreted here, as elsewhere (Nunn and Cook Citation2022), as meaning that places which later became islands were contiguous with the mainland at the time people first saw them. The minimum depth of ocean between such an island and the adjacent mainland can be plotted on a curve/envelope of postglacial sea-level history to allow calculation of a minimum age for island development, an approach used for numerous Australian coastal sites/stories (Nunn Citation2018; Nunn and Reid Citation2016) and elsewhere (Nunn Citation2022; Nunn et al. Citation2021, Citation2022).

For the eight islands associated with the Ngurunderi narrative, minimum depths and ages are listed in and shown graphically in . There are considerable uncertainties in the age estimates, arising from the imprecision of depth and paleosea-level data as well as contestable interpretations of narrative details, but it is nevertheless considered that these estimates provide a realistic chronology for these elements of the Ngurunderi narrative.

Figure 6. Sea-level changes around the coast of Australia within the past 13,000 years (after Lewis et al. Citation2013; Nunn and Reid Citation2016); the blue/shaded envelope represents the uncertainty of sea levels at particular points in time. Red/shaded boxes show the sea levels (as in ) at which each of the eight island-formation stories and that referring to the crossing of Backstairs Passage would most recently have been true. Ages in are calculated graphically from this figure.

Table 2. Nearshore islands referenced as having been created/visited by Ngurunderi with details of minimum depths that allow calculation of minimum ages for islandization (from ).

Submergence of Backstairs Passage

Before Ngurunderi summoned the ocean to flood Backstairs Passage and drown his wives, the narrative explains that people were able to walk across it from Fleurieu Peninsula to Kangaroo Island. In all stories bar one, Backstairs Passage remains inundated thereafter, a succession of events that can be interpreted as marking the point during the period of postglacial sea-level rise at which this land bridge was first wholly submerged (Nunn Citation2018; Nunn and Reid Citation2016). Based on , this event is dated to at least 11,000–10,100 cal BP.

In this section, acknowledging that variants of the Ngurunderi narrative have the land bridge starting in the east from either Cape Jervis or Blowhole Creek, minimum depths and ages are re-evaluated using more detailed bathymetric information. shows the bathymetry of Backstairs Passage, interpreted and redrawn from Australian Hydrographic Service chart AUS126 (revised 2010). The bathymetry shows that when sea level was 30 m lower than today, Backstairs Passage was much narrower; the modern Fleurieu Peninsula was contiguous with The Pages (islands) and with Yatala Shoal where minimum water depths of 4–5 m are found today. The east coast of Kangaroo Island also extended seawards, especially in the northeast. While Cape Jervis could well have been a place on the route to Kangaroo Island, the more central point of departure from (modern) Fleurieu Peninsula would have been Blowhole Creek, as most known variants of the Ngurunderi narrative state.

Figure 7. Current bathymetry of Backstairs Passage showing its geography today and when sea level was 10, 20 and 30 m lower. Based on published depth soundings (from Australian Hydrographic Service chart AUS126 [2010]), a land bridge across Backstairs Passage would have existed when the sea level was 32–35 m lower, estimated to have been at least 10,100–11,000 years ago (see and ). A likely crossing route is shown as a dashed line and suggests that the detail in most versions of the Ngurunderi narrative stating that this route began at Blowhole Creek (Tjirbuk) is correct.

![Figure 7. Current bathymetry of Backstairs Passage showing its geography today and when sea level was 10, 20 and 30 m lower. Based on published depth soundings (from Australian Hydrographic Service chart AUS126 [2010]), a land bridge across Backstairs Passage would have existed when the sea level was 32–35 m lower, estimated to have been at least 10,100–11,000 years ago (see Figure 6 and Table 2). A likely crossing route is shown as a dashed line and suggests that the detail in most versions of the Ngurunderi narrative stating that this route began at Blowhole Creek (Tjirbuk) is correct.](/cms/asset/b61b94df-4fb8-41d8-9893-c1057ada7977/uica_a_2337096_f0007_c.jpg)

The optimal crossing route involves a land bridge that would have still been passable when sea level was 32–35 m lower than today, calculated to have been approximately 11,000–10,100 cal BP (see ). No other parts of Backstairs Passage would have been passable on foot at this time. Sea-level rise would have led to the progressive narrowing of the land bridge and made its crossing increasingly riskier until a point at which it became impassable, a memorable occurrence worthy of encoding in contemporary oral traditions that came to underpin the Ngurunderi narrative.

There is a remarkable parallel from Scotland that supports this chain of inference, one involving the progressive submergence of the land bridge (or isthmus) connecting the Monach (Heisker) Islands to North Uist Island in the Outer Hebrides (Nunn Citation2022). Stories collected in the 1880s from one of the last remaining residents of the Monach Islands recalled that the isthmus-skerry (aoi-sgeir in Gaelic) connecting the two disappeared gradually and that “tradition still mentions the names of those who crossed these fords last, and the names of persons drowned in crossing” (Carmichael Citation1884, 464). Similar memorialization of ancestral beings may help explain why the story of the drowning of Ngurunderi’s wives has lasted so long, possibly more than 10 millennia, passed down orally across perhaps more than 400 generations. These Hebridean stories are estimated to have endured orally for around 7000 years (Nunn and Cook Citation2022).

Unpacking Ngurunderi: The time structure of the narrative

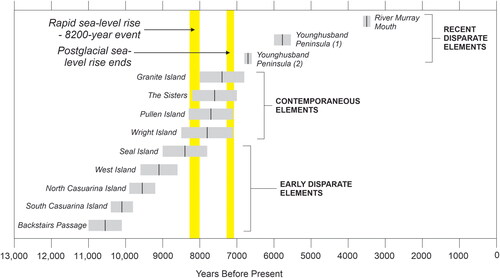

Having identified approximate ages for particular elements of the Ngurunderi narrative, it is now possible to look at the distribution of these and see whether anything can be discerned about its structure. shows each of the 12 dated elements organized from left to right in descending age order. Three groups of elements involving shoreline change are distinguishable and may be significant to understanding the evolution of the Ngurunderi narrative through time.

Figure 8. Dated elements of the Ngurunderi narrative arranged in descending-age order. Three groups of elements may be significant in understanding the evolution of the Ngurunderi narrative. The middle group (contemporaneous elements) may have been associated with rapid sea-level rise during the 8200-year event and the later group (recent disparate elements) with the end of postglacial sea-level rise.

The earliest group is one of five early disparate elements in which the oldest is the submergence of the last remaining land connection between Fleurieu Peninsula and Kangaroo Island. This may be the anchor event, the earliest and most transformative of the sequence that guided the interpretation of subsequent submergence events by local people. For example, once such events were ascribed to human action/control, then it was legitimate for later ones, such as the submergence of land bridges, to be attributed to a similar cause. Yet, given the incompleteness of the narrative record, it may be there was an even earlier anchor event, the rationalization of which by local people informed that of the submergence of Backstairs Passage. Such an event might have been the (rapid) submergence of either Gulf St Vincent or Spencer Gulf, the latter of which is estimated to have occurred at least 9330–12,460 cal BP and would likely have separated different Aboriginal groups and submerged some of the area’s most productive wetland ecosystems (Nunn Citation2018; Roberts et al. Citation2020).

The second group that can be recognized in is that of the four contemporaneous elements that occurred around the same time. While the fact of their submergence is dependent on geography, specifically coastal geomorphology, the likelihood of the memories of this submergence being preserved for more than seven millennia is more worthy of analysis. For it may well be that a trigger like the comparatively rapid short-lived rise of sea level during the (near-global) 8200-year event, in which sea level rose 6.5 m in 140 years (Alley et al. Citation1997; Smith et al. Citation2011), led to a series of rapid and irreversible coastal changes that greatly impacted local societies. As argued elsewhere, this so traumatized people in Australia and in parts of northwest Europe (Nunn Citation2018; Nunn et al. Citation2021), that these events would feature large in the collective resident psyche for generations, not least in case they should occur again (Nunn Citation2020); evidence for the effects of the 8200-year event has been detected along the Australian coast (Sanborn et al. Citation2020).

An alternative explanation for these contemporaneous elements is that stories about submergence had been continually remembered and retold, as expressions of human experience or trauma, but that these were regularly forgotten as new examples of submergence replaced them. Only the most recent of these stories are remembered today because they date from around the end of submergence; they were never displaced by later submergence stories because postglacial sea-level rise ended. This explanation acknowledges the likelihood that we are today looking only at a tiny subset of what was once a massive body of stories created by the peoples of South Australia within the past 12,000 years or more. For example, off the south coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula where six nearshore islands, each associated with Ngurunderi and shown in , exist today, there were formerly other islands, now wholly submerged, about which earlier generations undoubtedly had stories; perhaps when those islands vanished completely, the stories passed from the realm of remembered history into myth, a process described for submerged places in many other parts of the world (Nunn Citation2021).

The final group recognizable in the Ngurunderi narrative and shown in comprises the three recent disparate elements, which are regarded as opportunistic events, worth remembering and incorporating into oral traditions but not part of a coherent set of historically linked observations. Postglacial sea-level rise had ceased, coastal landscapes were now evolving in ways that presented new livelihood opportunities or constraints for local residents.

Discussion: Holocene human–environment interactions illuminated by ancient stories

While the approach taken in this paper is novel in its multidisciplinary approach to the use of ancient stories to illuminate environmental changes and human responses to these during the early Holocene, it is not unprecedented. Particularly among First Nations people of Canada, there has been considerable research that demonstrates many of their oldest narratives represent memories of past landscape-altering events, including those of coastline changes (Gauvreau and McLaren Citation2016) and the movements of ice bodies (Cruikshank Citation2001). Australia also provides similar examples, including Palawa memories of when Tasmania was connected to the mainland that may be 12,500 years old (Hamacher et al. Citation2023), and more detailed and inevitably more compelling analyses of more recent bodies of knowledge (Kearney, O'Leary, and Platten Citation2023; Smith Citation2019). Recent research demonstrates the potential of similar research in the Pacific Islands (Ballard Citation2020; Lancini et al. Citation2023; Urwin Citation2019).

This study shows that elements of ancestral Aboriginal Australian narratives, which include descriptions of landscape change, are plausibly based on observations made thousands of years ago, in some cases perhaps more than 10,000 years ago. The details in these stories include recollections of when modern islands were once part of the mainland and, conversely in the case of Younghusband Peninsula, when what were perhaps once islands became a continuous coastal barrier. Here we reiterate that such traditions convey much more complexity and nuance—they may relate to later interpretations and deep understandings of landscape transformations or relay the importance of social rules, for instance (Roberts et al. Citation2023).

While acknowledging the complexities inherent in Aboriginal traditions and the unavoidable unknowns involved in unpacking them, it seems likely that part of people’s motivation for preserving their memories of these transformative events was to inform subsequent generations that such things periodically occur and, while disruptive, are survivable. This motivation is explainable by the importance of conveying all knowledge held by one generation to the next to optimize its chances of survival (Charles and O'Brien Citation2020; Ross Citation1986). With specific reference to postglacial sea-level rise and the trauma felt by coastal dwellers who experienced its consequences, there are clear lessons for today when many coastal peoples are feeling apprehension for similar reasons (Nunn Citation2020; Woodroffe and Murray-Wallace Citation2012).

An important insight from this study is that ancient ancestral narratives like the Ngurunderi narrative are not mere fantasies or simply “articulate a relational ontology” (Taylor Citation2013, 94). They should not be marginalized for they represent knowledge systems and/or interpretations of memorable events in particular places as observed and understood by people whose means of acquiring and communicating important information was principally oral. Several studies refute the supposedly self-evident idea that information storage and understanding are less in oral than literate contexts (Kelly Citation2015; Vansina Citation1985) and lay the foundations for more balanced treatments of what has often been dismissed by scientists as myth or legend (Piccardi and Masse Citation2007; Vitaliano Citation1973). In this study, it is argued that the Ngurunderi narrative contains information about the formation of Younghusband Peninsula, possibly a pre-modern blockage of the Murray Mouth; it contains reference to a time when at least eight now-nearshore islands were formerly contiguous with adjacent mainlands; and it recalls the time when the land bridge which last connected modern Kangaroo Island and Fleurieu Peninsula was submerged. All such events can also be inferred from models of postglacial landform evolution in South Australia.

Knowing that Aboriginal people lived in South Australia long before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ∼22–18,000 cal BP) when sea level was more than 125 m lower than today (Hamm et al. Citation2016; Hope et al. Citation1977; Westell et al. Citation2020) allows the Ngurunderi story to be put into context. People would likely have occupied the whole of the Lacepede Bay/Shelf at the time until sea level started rising (post-LGM) and drove people slowly inland (Bourman, Murray-Wallace, et al. Citation2018; Ngarrindjeri Nation and Hemming Citation2018; Wilson Citation2017). The Ngurunderi narrative recalls and interprets only episodes from the last part of this process (see ) so it is almost certain that comparable stories existed before this time, recalling people’s anxieties about coastal land lossFootnote2 and their (evolving) understanding about how it might be stopped. Fragments of extant stories elsewhere in Australia articulate this trauma: for example, the report from the fringe of the Nullarbor Plains that only “prompt action” stopped the ocean from “inundating the country completely” (Berndt and Berndt Citation1965, 401). Stopping continuing inundation was both something that many Aboriginal groups saw as a practical challenge—some erected artificial barriers—but also as a “spiritual” one, as might be represented by the stone arrangements along the Australian coast likely to be “associated with ritual control of extreme tidal regimes” (McNiven Citation2008, 155). Similar interpretations are used to explain coastal stone arrangements in northwest France and elsewhere (Cassen et al. Citation2011; Nunn Citation2021).

Conclusion

Histories of multi-millennial landscape change are conventionally calibrated using a range of techniques based on geological/stratigraphic or radiometric principles. While unquestionably robust, such approaches cannot answer all questions about landscape evolution, sometimes because there is insufficient high-resolution material (typically sedimentary) available to analyze, sometimes because it is uncertain what particular strata represent. But perhaps most profoundly, such approaches cannot humanize the past; they cannot tell us how particular events may have affected particular groups of humans, perhaps by either constraining or broadening their activities, and, conversely, they cannot tell us what role humans may have played in landscape evolution (perhaps through de-vegetation or the intentional modification of landforms) and their motivations for doing so (Nikulina et al. Citation2022; Prober et al. Citation2016; Rosen et al. Citation2017).

In one sense, such challenges map the interface of archaeology/history and the geosciences, a place where some attempts at crossover have occurred although most researchers avoid such territory, favoring the security of their disciplinary mainstreams. In another sense, such challenges also map the cultural interface between Indigenous/traditional knowledges and western science-based knowledges, not in order to validate one with the other, but to demonstrate the true nature of Indigenous/traditional knowledges as science filtered through contrasting worldviews and contextualized within particular places (Nakata et al. Citation2012). Yet in the Anthropocene, where humans are massively implicated by global change and where global change will have profound impacts on future generations of humans, the need to reassess the past in similar terms has never been more pressing. There are innumerable lessons for managing our collective future that we can draw from the experiences of ancestors around the world in encountering and responding to landscape change (Fletcher et al. Citation2021; McMillen, Ticktin, and Springer Citation2017; Nunn Citation2020; Yunkaporta Citation2019). A future in which all available and relevant knowledges are equally respected by all and become “braided” to develop the best possible plans for coping with climate adversity is achievable (Atalay Citation2020; Roberts et al. Citation2023).

Almost 150 years ago, it was noted that stories about Ngurunderi (Nurundere) “are fast fading from the memory of the Aborigines” and that “it is only from the old people that the particulars of them can be obtained” (Woods Citation1879, 58). Yet the stories and teachings of Ngurunderi live on amongst Ngarrindjeri today and community members continue to honor the knowledge contained within them (Ngarrindjeri Nation and Hemming Citation2018). Similar stories exist elsewhere in the world and might also be worth unpacking to allow a fuller understanding of late Quaternary landscape evolution.

Acknowledgements

All narrative information cited in this study comes from published sources and we acknowledge with respect and gratitude the insights of the Indigenous Australians who sustained these narratives for thousands of years across hundreds of generations. The names of most of these people are lost. Yet in reference to the Ngurunderi narrative, most of Ronald Berndt’s information was obtained from the Yaraldi-Ngarrindjeri men Albert Karlowan (Tara’mindjerup) and Mark Wilson (Thralum), and Piltindjeri-Ngarrindjeri woman Margaret “Pinkie” Mack (Katipelvild). Most of Norman Tindale’s information came from Tangane-Ngarrindjeri man Clarence Long (Milerum). The Ngarrindjeri Aboriginal Corporation (NAC) are the formal partner on this research project, but we acknowledge all Ngarrindjeri peoples who contribute to these narratives and work on Ngarrindjeri Ruwe. Three anonymous referees greatly improved the original manuscript as did the editorial guidance of Scott M. Fitzpatrick.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this regard the work undertaken for this article has been permitted and supported by the Ngarrindjeri Aboriginal Corporation (which is also a co-author of the research) and Ngarrindjeri scholar, Dr Chris Wilson.

2 It has been estimated that around 10,000 years ago off the Nullarbor coast of southern Australia, the coastline was moving landwards at the rate of more than 1 m every week. Another study suggests that during the more rapid periods of postglacial sea-level rise, people living along the Arnhem Land coast in northern Australia would have witnessed the shoreline moving landwards by 5 km every year (Flood Citation2006, 194).

References

- Alley, R. B., P. A. Mayewski, T. Sowers, M. Stuiver, K. C. Taylor, and P. U. Clark. 1997. Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago. Geology 25 (6):483–6. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0483:HCIAPW>2.3.CO;2

- Atalay, S. 2020. Indigenous science for a world in crisis. Public Archaeology 19 (1–4):37–52. doi: 10.1080/14655187.2020.1781492

- Bacigalupo, A. M. 2013. Mapuche struggles to obliterate dominant history: Mythohistory, spiritual agency and shamanic historical consciousness in southern Chile. Identities 20 (1):77–95. doi: 10.1080/1070289x.2012.757551.

- Ballard, C. 2020. The Lizard in the Volcano: Narratives of the Kuwae eruption. The Contemporary Pacific 32 (1):98–123. doi: 10.1353/cp.2020.0005

- Barber, E. W., and P. T. Barber. 2004. When they severed earth from sky: How the human mind shapes myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bell, D. 1998. Ngarrindjeri wurruwarrin: A world that is, was, and will be. North Melbourne: Spinifex.

- Berndt, R. M. 1940. Some aspects of Jaralde culture, South Australia. Oceania 11 (2):164–85. doi: 10.1002/j.1834-4461.1940.tb00283.x

- Berndt, R. M., and C. H. Berndt. 1965. The world of the first Australians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Berndt, R. M., C. H. Berndt, and J. E. Stanton. 1993. A world that was: The Yaraldi of the Murray River and the lakes, South Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Bloch, L. 2019. Oral traditions and mounds, owls and movement at Poverty Point: An archaeological ethnography of multispecies embodiments and everyday life. Journal of Social Archaeology 19 (3):356–78. doi: 10.1177/1469605319846985.

- Bourman, R. P., N. Harvey, K. F. James, C. V. Murray-Wallace, A. P. Belperio, and D. D. Ryan. 2018. The mouth of the River Murray, South Australia. In Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth Region (Yarluwar-Ruwe), ed. L. M. Mosley, Q. Ye, S. Shepherd, S. Hemming and R. Fitzpatrick, 103–20. Adelaide: University of Adelaide/Royal Society of South Australia.

- Bourman, R. P., C. V. Murray-Wallace, D. D. Ryan, A. P. Belperio, and N. Harvey. 2018. Geomorphological evolution of the River Murray Estuary, South Australia. In Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth Region (Yarluwar-Ruwe), ed. L. M. Mosley, Q. Ye, S. Shepherd, S. Hemming and R. Fitzpatrick, 71–102. Adelaide: University of Adelaide/Royal Society of South Australia.

- Campbell, A. H. 1967. Aboriginal traditions and the prehistory of Australia. Mankind 6 (10):476–81.

- Cann, J. H., R. P. Bourman, and E. J. Barnett. 2000. Holocene foraminifera as indicators of relative estuarine-lagoonal and oceanic influences in estuarine sediments of the River Murray, South Australia. Quaternary Research 53 (3):378–91. doi: 10.1006/qres.2000.2129

- Carmichael, A. 1884. Grazing and agrestic customs of the Outer Hebrides (Appendix A (XCIX)). In Report into the condition of the crofters and cottars in the highlands and islands of Scotland, ed. Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Inquiry, 451–82. Edinburgh: Neill.

- Cassen, S., A. Baltzer, A. Lorin, J. Fournier, and D. Sellier. 2011. Submarine Neolithic stone rows near Carnac (Morbihan), France: Preliminary results from acoustic and underwater survey. In Submerged Prehistory, ed. J. Benjamin, C. Bonsall, C. Pickard and A. Fischer, 99–110. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Cawthorne, W. A. 1926. (for 1844). Rough notes on the manners and customs of the natives. Royal Geographical Society of Australasia 27:47–77.

- Charles, J. A., and L. O'Brien. 2020. The survival of Aboriginal Australians through the harshest time in human history: Community-strength. International Journal of Indigenous Health 15 (1):5–20. doi: 10.32799/ijih.v15i1.33925.

- Clarke, P. A. 1995. Myth as history? The Ngurunderi Dreaming of the Lower Murray, South Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum 28 (2):143–57.

- Cruikshank, J. 2001. Glaciers and climate change: Perspectives from oral tradition. Arctic 54 (4):377–93. doi: 10.14430/arctic795

- Cruikshank, J. 2007. Do glaciers listen? Local knowledge, colonial encounters and social imagination. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Dillenburg, S. R., P. A. Hesp, R. Keane, G. M. da Silva, A. O. Sawakuchi, I. Moffat, E. G. Barboza, and V. J. B. Bitencourt. 2020. Geochronology and evolution of a complex barrier, Younghusband Peninsula, South Australia. Geomorphology 354:107044. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107044.

- Draper, N. 2015. Islands of the dead? Prehistoric occupation of Kangaroo Island and other southern offshore islands and watercraft use by Aboriginal Australians. Quaternary International 385:229–42. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.008.

- Echo-Hawk, R. C. 2000. Ancient history in the new world: Integrating oral traditions and the archaeological record in deep time. American Antiquity 65 (2):267–90. doi: 10.2307/2694059.

- Fakhriati, F., D. Nasri, M. Mu’jizah, Y. M. Supriatin, A. Supriadi, M. Musfeptial, and K. Kustini. 2023. Making peace with disaster: A study of earthquake disaster communication through manuscripts and oral traditions. Progress in Disaster Science 18:100287. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2023. 10.1016/j.pdisas.2023.100287

- Fletcher, M.-S., A. Romano, S. Connor, M. Mariani, and S. Y. Maezumi. 2021. Catastrophic bushfires, Indigenous fire knowledge and reframing science in southeast Australia. Fire 4 (3):61. doi: 10.3390/fire4030061

- Flood, J. 1995. Archaeology of the Dreamtime: The story of prehistoric Australia and its people. Revised ed. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- Flood, J. 2006. The original Australians: Story of the Aboriginal people. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin.

- Gale, M.-A. 2000. Poor Bugger Whitefella Got No Dreaming: The representation and appropriation of published Dreaming narratives with special reference to David Unaipon’s writings., PhD, Linguistics and English, University of Adelaide.

- Gauvreau, A., and D. McLaren. 2016. Imbricating Indigenous oral narratives and archaeology on the northwest coast of North America. Hunter Gatherer Research 2 (3):303–25. doi: 10.3828/hgr.2016.22

- Hamacher, D. 2022. The first astronomers: How Indigenous elders read the stars. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

- Hamacher, D., P. D. Nunn, M. Gantevoort, R. Taylor, G. Lehman, K. H. A. Law, and M. Miles. 2023. The archaeology of orality: Dating Tasmanian Aboriginal oral traditions to the Late Pleistocene. Journal of Archaeological Science 159:105819. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105819.

- Hamm, G., P. Mitchell, L. J. Arnold, G. J. Prideaux, D. Questiaux, N. A. Spooner, V. A. Levchenko, E. C. Foley, T. H. Worthy, B. Stephenson, et al. 2016. Cultural innovation and megafauna interaction in the early settlement of arid Australia. Nature 539 (7628):280–3. doi: 10.1038/nature20125.

- Harvey, N. 2006. Holocene coastal evolution: Barriers, beach ridges, and tidal flats of South Australia. Journal of Coastal Research 221:90–9. doi: 10.2112/05a-0008.1.

- Harvey, N., R. P. Bourman, and K. James. 2006. Evolution of the Younghusband Peninsula, South Australia: New evidence from the northern tip. South Australian Geographical Journal105:37–50.

- Hemming, S., P. G. Jones, and P. Clarke. 1989. Ngurunderi: An aboriginal dreaming. Adelaide: South Australian Museum.

- Henige, D. 2009. Impossible to disprove yet impossible to believe: The unforgiving epistemology of deep-time oral tradition. History in Africa 36 (1):127–234. doi: 10.1353/hia.2010.0014

- Holdgate, G. R., B. Wagstaff, and S. J. Gallagher. 2011. Did Port Phillip Bay nearly dry up between∼ 2800 and 1000 cal. yr BP? Bay floor channelling evidence, seismic and core dating. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 58 (2):157–75. doi: 10.1080/08120099.2011.546429

- Hope, J. H., R. J. Lampert, E. Edmondson, M. J. Smith, and G. F. Van Tets. 1977. Late Pleistocene faunal remains from Seton rock shelter, Kangaroo Island, South Australia. Journal of Biogeography 4 (4):363–85. doi: 10.2307/3038194

- Kearney, A., M. O'Leary, and S. Platten. 2023. Sea Country: Plurality and knowledge of saltwater territories in indigenous Australian contexts. The Geographical Journal 189 (1):104–16. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12466.

- Kelley, K. 2020. Downy Home Man and Chacoan Macaws: How Dine oral tradition can enhance archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Research 76 (3):274–95. doi: 10.1086/709803.

- Kelly, L. 2015. Knowledge and power in prehistoric societies: Orality, memory and the transmission of culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kirch, P. V. 2018. Voices on the wind, traces in the earth: Integrating oral narrative and archaeology in Polynesian history. Journal of the Polynesian Society 127 (3):275–306. doi: 10.15286/jps.127.3.275-306.

- Lampert, R. J. 1981. The Great Kartan Mystery. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Lancini, L., P. D. Nunn, M. Nanuku, K. Tavola, T. Bolea, P. Geraghty, and R. Compatangelo-Soussignan. 2023. Driva Qele/Stealing Earth: Oral accounts of the volcanic eruption of Nabukelevu (Mt Washington), Kadavu Island (Fiji) ∼2500 years ago. Oral Tradition 36 (1):63–90.

- Lewis, S. E., C. R. Sloss, C. V. Murray-Wallace, C. D. Woodroffe, and S. G. Smithers. 2013. Post-glacial sea-level changes around the Australian margin: A review. Quaternary Science Reviews 74:115–38. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.09.006.

- Luebbers, R. A. 1981. The Coorong Report: An archaeological study of the Southern Younghusband Peninsula. Adelaide: South Australia Department for Environment and Planning.

- Luebbers, R. A. 1982. The Coorong Report: An archaeological study of the Northern Younghusband Peninsula. Adelaide: South Australia Department for Environment and Planning.

- Marker, M. 2015. Borders and the borderless Coast Salish: Decolonising historiographies of Indigenous schooling. History of Education 44 (4):480–502. doi: 10.1080/0046760x.2015.1015626.

- Masse, W. B. 2007. The archaeology and anthropology of Quaternary period cosmic impact. In Comet/Asteroid Impacts and Human Society, ed. P.T. Bobrowsky and H. Rickman, 25–70. Berlin: Springer.

- McMillen, H. L., T. Ticktin, and H. K. Springer. 2017. The future is behind us: Traditional ecological knowledge and resilience over time on Hawai’i Island. Regional Environmental Change 17 (2):579–92. doi: 10.1007/s10113-016-1032-1.

- McNiven, I. J. 2008. Sentient sea: Seascapes as spiritscapes. In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology, ed. Bruno David and Julian Thomas, 149–57. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Meyer, H. E. A. 1846. Manners and customs of the Aborigines of the Encounter Bay tribes, South Australia. Adelaide: Dehane.

- Morphy, F., H. Morphy, P. Faulkner, and M. Barber. 2020. Toponyms from 3000 years ago? Implications for the history and structure of the Yolŋu social formation in north-east Arnhem Land. Archaeology in Oceania 55 (3):153–67. doi: 10.1002/arco.5213.

- Murray-Wallace, C. V., R. P. Bourman, J. R. Prescott, F. Williams, D. M. Price, and A. P. Belperio. 2010. Aminostratigraphy and thermoluminescence dating of coastal aeolianites and the later Quaternary history of a failed delta: The River Murray mouth region, South Australia. Quaternary Geochronology 5 (1):28–49. doi: 10.1016/j.quageo.2009.09.011.

- Nakata, N. M., V. Nakata, S. Keech, and R. Bolt. 2012. Decolonial goals and pedagogies for Indigenous studies. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1):120–40.

- Ngarrindjeri Nation, and S. Hemming. 2018. Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri country and culture. In Natural history of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth Region (Yarluwar-Ruwe), ed. L.M. Mosley, Q. Ye, S. Shepherd, S. Hemming and R. Fitzpatrick, 3–20. Adelaide: University of Adelaide/Royal Society of South Australia.

- Nikulina, A., K. MacDonald, F. Scherjon, E. A. Pearce, M. Davoli, J. C. Svenning, E. Vella, M. J. Gaillard, A. Zapolska, F. Arthur, et al. 2022. Tracking hunter-gatherer impact on vegetation in Last Interglacial and Holocene Europe: Proxies and challenges. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 29 (3):989–1033. doi: 10.1007/s10816-021-09546-2.

- Nunn, P. D. 2018. The edge of memory: Ancient stories, oral tradition and the post-glacial world. London: Bloomsbury.

- Nunn, P. D. 2020. In anticipation of extirpation: How ancient peoples rationalized and responded to postglacial sea-level rise … and why it matters. Environmental Humanities 12 (1):113–31. doi: 10.1215/22011919-8142231

- Nunn, P. D. 2021. Worlds in shadow: Submerged lands in science, memory and myth. London: Bloomsbury.

- Nunn, P. D. 2022. First a wudd, and syne a sea: Postglacial coastal change of Scotland recalled in ancient stories. Scottish Geographical Journal 138 (1–2):73–102. doi: 10.1080/14702541.2022.2110610.

- Nunn, P. D., and M. Cook. 2022. Island tales: Culturally-filtered narratives about island creation through land submergence incorporate millennia-old memories of postglacial sea-level rise. World Archaeology 54 (1):29–51. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2022.2077821

- Nunn, P. D., A. Creach, W. R. Gehrels, S. L. Bradley, I. Armit, P. Stéphan, F. Sturt, and A. Baltzer. 2021. Observations of postglacial sea-level rise in northwest European traditions. Geoarchaeology 37 (4):577–93. doi: 10.1002/gea.21898.

- Nunn, P. D., L. Lancini, L. Franks, R. Compatangelo-Soussignan, and A. McCallum. 2019. Maar stories: How oral traditions aid understanding of maar volcanism and associated phenomena during pre-literate times. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (5):1618–31. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2019.1574550.

- Nunn, P. D., and N. J. Reid. 2016. Aboriginal memories of inundation of the Australian coast dating from more than 7000 years ago. Australian Geographer 47 (1):11–47. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2015.1077539

- Nunn, P. D., I. Ward, P. Stéphan, A. McCallum, R. Gehrels, G. Carey, A. Clarke, M. Cook, P. Geraghty, D. Guilfoyle, et al. 2022. Human observations of Late Quaternary coastal change: Examples from Australia, Europe and the Pacific Islands. Quaternary International 638–9:212–24. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2022.06.016

- Ong, W. 1982. Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Routledge.

- Piccardi, L., and W.B. Masse, eds. 2007. Myth and geology. London: Geological Society of London.

- Piccardi, L., C. Monti, O. Vaselli, F. Tassi, K. Gaki-Papanastassiou, and D. Papanastassiou. 2008. Scent of a myth: Tectonics, geochemistry and geomythology at Delphi (Greece). Journal of the Geological Society 165 (1):5–18. doi: 10.1144/0016-76492007-055.

- Prober, S. M., E. Yuen, M. H. O'Connor, and L. Schultz. 2016. Ngadju kala: Australian Aboriginal fire knowledge in the Great Western Woodlands. Austral Ecology 41 (7):716–32. doi: 10.1111/aec.12377.

- Roberts, A. L., A. Mollenmans, L. I. Rigney, and G. Bailey. 2020. Marine Transgression, Aboriginal Narratives and the Creation of Yorke Peninsula/Guuranda, South Australia. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 15 (3):305–32. doi: 10.1080/15564894.2019.1570990.

- Roberts, A. L., C. Westell, M. Fairhead, and J. M. Lopez. 2023. “Braiding Knowledge” about the peopling of the River Murray (Rinta) in South Australia: Ancestral narratives, geomorphological interpretations and archaeological evidence. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 71:101524. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2023.101524.

- Rosen, A., R. Macphail, L. Liu, X. C. Chen, and A. Weisskopf. 2017. Rising social complexity, agricultural intensification, and the earliest rice paddies on the Loess Plateau of northern China. Quaternary International 437:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.013.

- Ross, M. C. 1986. Australian Aboriginal oral traditions. Oral Tradition 1 (2):231–71.

- Sanborn, K. L., J. M. Webster, G. E. Webb, J. C. Braga, M. Humblet, L. Nothdurft, M. A. Patterson, B. Dechnik, S. Warner, T. Graham, et al. 2020. A new model of Holocene reef initiation and growth in response to sea-level rise on the Southern Great Barrier Reef. Sedimentary Geology 397:105556. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2019.105556.

- Sansom, B. 2006. The brief reach of history and the limitation of recall in traditional aboriginal societies and cultures. Oceania 76 (2):150–72. doi: 10.1002/j.1834-4461.2006.tb03042.x

- Sharpe, M., and D. Tunbridge. 1999. Traditions of extinct animals, changing sea-levels and volcanoes among Australian Aboriginals: Evidence from linguistic and ethnographic research. In Archaeology and language I: Theoretical and methodological orientations, ed. R. Blench and M. Spriggs, 345–61. London: Routledge.

- Short, A. D., and P. A. Hesp. 1984. Wave, beach and dune interactions in southeastern Australia. Marine Geology 48 (3-4):259–84. doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(82)90100-1.

- Smith, D. E., S. Harrison, C. R. Firth, and J. T. Jordan. 2011. The early Holocene sea level rise. Quaternary Science Reviews 30 (15-16):1846–60. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.04.019.

- Smith, M. A. 2019. The historiography of kardimarkara: Reading a desert tradition as cultural memory of the remote past. Journal of Social Archaeology 19 (1):47–66. doi: doi: 10.1177/1469605318817685.

- Smith, W. R. 1930. Myths and legends of the Australian Aboriginals. London: Harrap.

- Sugiyama, M. S. 2021. Co-occurrence of ostensive communication and generalizable knowledge in forager storytelling: Cross-cultural evidence of teaching in forager societies. Human Nature-an Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective 32 (1):279–300. doi: 10.1007/s12110-021-09385-w.

- Taggart, D. 2018. How Thor lost his thunder: The changing faces of an old Norse god. London: Routledge.

- Taplin, G. 1879. The Narrinyeri: An account of the tribes of South Australian Aborigines inhabiting the country around the lakes Alexandrina, Albert and Coorong, and the lower part of the River Murray. Adelaide: Government Printer.

- Taylor, A. 2013. Reconfiguring the natures of childhood. London: Routledge.

- Tindale, N. B. 1937. Native songs of the south-east of South Australia. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia 61:107–20.

- Tindale, N. B., and B. G. Maegraith. 1931. Traces of an extinct Aboriginal population on Kangaroo Island. Records of the South Australian Museum 4 (3):275–89.

- Urwin, C. 2019. Excavating and interpreting ancestral action: Stories from the subsurface of Orokolo Bay, Papua New Guinea. Journal of Social Archaeology 19 (3):279–306. doi: 10.1177/1469605319845441.

- Vansina, J. 1985. Oral traditions as history. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Vitaliano, D. B. 1973. Legends of the earth: Their geologic origins. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Westell, C., A. Roberts, M. Morrison, and G. Jacobsen 2020. Initial results and observations on a radiocarbon dating program in the Riverland region of South Australia. Australian Archaeology 86 (2):160–75. doi: 10.1080/03122417.2020.1787928.

- Wilkie, B., F. Cahir, and I. D. Clark. 2020. Volcanism in Aboriginal Australian oral traditions: Ethnographic evidence from the Newer Volcanics Province. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 403:106999. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2020.106999.

- Wilson, C. J. 2017. Holocene Archaeology and Ngarrindjeri Ruew/Ruwar (Land, Body, Spirit): a critical Indigenous approach to understanding the lower Murray River, South Australia, PhD. diss., Flinders University.

- Woodroffe, C. D., and C. V. Murray-Wallace. 2012. Sea-level rise and coastal change: The past as a guide to the future. Quaternary Science Reviews 54:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.05.009.

- Woods, J. D. 1879. The native tribes of South Australia. Adelaide: Wigg.

- Yunkaporta, T. 2019. Sand talk: How Indigenous thinking can save the world. Melbourne: Text Publishing.