Abstract

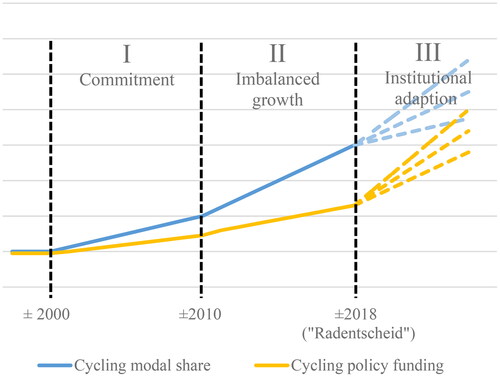

Cycling rates have grown consistently over recent years in cities across the globe. Nevertheless, the lack of policies to promote cycling results in dissatisfaction among cyclists in many cities. In response to this situation, local grassroots initiatives have emerged to pursue more ambitious cycling policies in German cities. However, there is limited knowledge of how grassroots movements influence the cycling policy agenda. Against this background, our article explores the relevance of the grassroots movement “Radentscheid” in four major German cities (Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, and Hamburg) regarding institutionalizing cycling policymaking. By combining exploratory document analysis, expert interviews, and an analysis of secondary data, we show that the development of cycling over the last two decades in these cities follows three stages: (i) Commitment, when cycling is put on the political agenda; (ii) Imbalanced growth, characterized by a strong increase in cycling but little progress in cycling policies and a decrease in cycling satisfaction; and (iii) Institutional adaptation, when cycling becomes a key issue for local governments due to the pressure from the grassroots movement “Radentscheid”. This paper closes with a discussion of the main results and policy recommendations.

1. Introduction

A notable cycling boom has emerged in many countries over the last few years, especially in highly urbanized areas (Pucher & Buehler, Citation2021; Schepers et al., Citation2021). Cycling is seen as a sustainable, healthy, and efficient alternative to challenge the car’s dominant position (Agarwal et al., Citation2018; Fishman, Citation2016) as well as a means to improve the quality of life in cities (Lanzendorf et al., Citation2022). For decades, pioneering cycling cities, such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen, have steadily expanded their cycling infrastructure and consequently increased cycling levels and improved quality of life (Pucher & Buehler, Citation2008; Zhao et al., Citation2018). Local authorities in many other cities have shown a growing interest in making urban environments more cycle friendly (Carstensen & Ebert, Citation2012; Gu et al., Citation2021; Pucher et al., Citation2011). For this purpose, three types of measures have been implemented. They relate to infrastructure, regulation, and communication (Marrana & Serdoura, Citation2017; Pucher et al., Citation2010; Winters et al., Citation2017).

Infrastructure measures are probably the most common, as the quality and quantity of cycling infrastructures shape basic cycling conditions (Adam et al., Citation2020; Harms et al., Citation2016; Mölenberg et al., Citation2019; Pucher et al., Citation2010; Yang et al., Citation2019). Important examples include the expansion of cycling networks, traffic-calmed roadways (Buehler & Dill, Citation2016; Schröter et al., Citation2021), the design of intersections (Bahmankhah et al., Citation2019; Casello et al., Citation2017), bicycle parking facilities, and built environment improvements (Ewing & Cervero, Citation2010; Handy et al., Citation2002; Timms & Tight, Citation2010). Regulatory measures refer to the rules that have to be followed by road users, such as rights of way, mandatory use of certain road segments, parking and congestion pricing, and traffic calming or car-free zones (Blitz & Lanzendorf, Citation2020; Handy et al., Citation2014; Heinen & Handy, Citation2021; Goodman et al., Citation2013; Piatkowski et al., Citation2019). Only some of these policies can be changed on the local level. Communication measures focus on providing cycling-related travel information (e.g. road signs, cycling maps, and personalized route planners) and promoting cycling through festivals, media campaigns, competitions, incentives, and education or training programs, especially for certain, inexperienced groups, such as women and immigrants (Albert de la Bruhèze & Oldenziel, Citation2018; Marrana & Serdoura, Citation2017; Pucher & Buehler, Citation2008; Pucher et al., Citation2010; van der Kloof, Citation2015; Yang et al., Citation2010).

Despite the notable advances in supporting cycling, dissatisfaction with cycling-related planning, policies, and infrastructures still prevails (Haustein et al., Citation2020; Peters, Citation2021; Ruhrort, Citation2019). For example, Lanzendorf and Busch‐Geertsema (Citation2014) report a cycling boom in the first decade of this century for four large German cities (Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Munich), but the actions taken by local authorities remained slow and lagged far behind the expectations of many cyclists and failed to institutionalize cycling.

In this article, we understand the social institutionalization of cycling to mean not just the improved role of cycling in related organizations, most importantly transport planning departments. Despite the need to improve the role of cycling in these organizations (e.g. by increasing the number of cycling planners or by giving priority to cycling in transforming urban transport), we, more generally, understand social institutions in a broader sense as the whole “complex of positions, roles, norms and values […] organizing relatively stable patterns of human activity” (Turner, Citation1997, p. 6) and, therefore, “more enduring features of social life” (Giddens, Citation1984, p. 24; Miller, Citation2019) that need to change for the institutionalization of cycling. These include the belief of local experts, politicians, and the population that cycling conditions need to be improved and that a car-oriented traffic planning strategy may not accommodate cycling adequately.

Without the social institutionalization of cycling, dissatisfaction with cycling conditions in many cities has resulted in the rise of local grassroots movements. These informal organizations put pressure on local governments to support the implementation of better cycling measures (Aldred, Citation2013; Becker & Sterz, Citation2021; Kopf, Citation2016). Popular grassroots movements include “Critical Mass” in many cities worldwide (Costantini, Citation2019; Henderson, Citation2013), “Londoners on Bikes” (Aldred, Citation2013), “Jugo cikling kampanja” in Belgrade (Kopf, Citation2016), “Zielone Mazowsze” in Warsaw (Sharonova, Citation2014) and “Teusacatubi” in Bogotá (Jensen, Citation2017).

Existing research argues that grassroots movements are key to carrying out pro-change trends in cycling and making planning processes more robust, transparent, and democratic (Aldred, Citation2012; Sagaris, Citation2014; Sagaris & Ortuzar, Citation2015). However, current studies are yet to explore whether grassroots movements can trigger institutional changes in cycling-related policies at the local level. Against this background, our article explores the continuing cycling boom in Germany since 2010 by revealing similar development patterns in four case studies and their interactions with the grassroots movement “Radentscheid”, which started in 2015 (Schneidemesser, Citation2021). Furthermore, we will argue that in these cases it is social action—not the implementation of cycling-friendly measures—that triggered an increase in the number of cyclists. Local cyclists and citizens in our case studies created political pressure with their respective grassroots movement for implementing these policies at a moment when the cycling boom was already clearly visible in daily travel patterns. Bicycle use and support among the population were, therefore already evident before policies were implemented. This relationship contradicts conventional findings and many studies, which argue that comprehensive measures of cycling promotion are crucial for a positive perception of cycling and a higher share of cyclists on the road (Hull & O’Holleran, Citation2014; Marqués et al., Citation2015; Mölenberg et al., Citation2019; Pucher & Buehler, Citation2008).

As in Lanzendorf and Busch‐Geertsema (Citation2014), the German cities of Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, and Frankfurt were taken as case studies for at least four reasons: (i) they are among the five largest cities in Germany; (ii) public authorities in each of the cities have implemented policy packages in the last two decades aiming to increase cycling levels; (iii) a local grassroots movement, “Radentscheid”, emerged in each city; and (iv) significant quantitative and qualitative data, as well as time series, are available.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews earlier research on cycling-related grassroots movements, specifically considering the Radentscheid initiative in German cities. Section 3 describes the research design, while Section 4 summarizes the development of cycling policy and planning in the four German study cities over the past 20 years. Section 5 develops a three-stage model explaining the similar evolution of local cycling use and planning in the case study cities. Section 6 concludes the paper by discussing the main findings and their implications for transport planning.

2. Local cycling-related grassroots movements

Civic engagement aimed at drawing attention to cycling and demanding better cycling infrastructure has been around for a long time. The growing popularity of cycling in recent years has re-energized the active involvement of civil society in local cycling initiatives (Marletto & Sillig, Citation2019). Large cycling-related grassroots movements emerged in the 1960s and 1970s in response to ongoing environmental degradation and the energy crisis in Europe and America (Carstensen & Ebert, Citation2012; Marletto & Sillig, Citation2019). The Netherlands and Copenhagen are two examples where actions undertaken by grassroots movements had an impact on the policies that significantly improved bicycle traffic (e.g. car-restricted and low-speed areas) and contributed to high cycling shares (Bruno et al., Citation2021; Emanuel, Citation2019). Different circumstances in other places (e.g. less cycling tradition or more car-centric planning) led to the failure of comparable movements in most other regions (Horton, Citation2006; Kopf, Citation2016). One of the implications of the emerging global environmental policy agenda in the 1990s was the resurgence of cycling as a sustainable mode of transport, particularly in the context of local policies (Aldred, Citation2012; Pucher et al., Citation2011). This led to large-scale civic engagement to fight for more cycling-friendly cities (Batterbury, Citation2003; Popan, Citation2019; Fernandez‐Heredia & Fernandez‐Sanchez, Citation2020). “Critical Mass”, probably the most well-known and widespread initiatives (as it is in more than 300 cities), started in 1992 in San Francisco (Henderson, Citation2013; Popan, Citation2019).

Since then, large groups of cyclists have gathered regularly to ride together, celebrate cycling and block streets and intersections to reclaim traffic space from cars (Furness, Citation2010). Although Critical Mass was founded due to dissatisfaction with the conditions for cycling, the initiatives usually refrain from demands for concrete measures and lobbying. For this reason, they are often described as “apolitical” (Carlsson, Citation2002). While they have brought cycling to public and media attention and consequently serve as a lever for cycling-related communication strategies (Blickstein & Hanson, Citation2001), infrastructure-related measures were only addressed in a few cases and after a long time. In contrast, for example, the grassroots movement “Londoners on Bikes” explicitly pursued political goals by drawing attention to cycling issues and by advocating for a mayoral candidate they believed would best support cycling (Aldred, Citation2013).

Similarly to Critical Mass, different grassroots movements have emerged in Latin America and Eastern Europe over the last decade. A significant example is the “Ciclocolectivos”, a movement found in different Colombian cities (Jensen, Citation2017). With their actions (e.g. conducting joint bicycle rides at night and communication campaigns for better cycling conditions), these initiatives aim to make cycling a safer experience but also make a claim for infrastructure-related policies. A similar form of protest has been organized by the group “Bicicletada” in various Brazilian cities to campaign for a more favorable cycle infrastructure (Jones & de Azevedo, Citation2013). Another relevant grassroots movement is “Ciudad Viva”. This started in Santiago de Chile and was triggered by a protest movement against an inner-city highway construction. The movement resulted in an intensive exchange with municipal planners and the active participation of citizens in cycling planning processes (Sagaris, Citation2014). It is worth noting the “Bicicultura” movement, also from Santiago de Chile, whose members became part of a consortium to evaluate national regulatory policies that initiated legislative changes to reduce maximum speeds in urban areas (Sagaris & Ortuzar, Citation2015).

The cycling movements in Eastern European countries have mainly served to gain the commitment of local authorities to consider cycling in their planning documents. The Polish movement “Zielone Mazowsze”, for example, compelled local government to include infrastructure-related measures within Warsaw’s master plan via direct contact with politicians (Sharonova, Citation2014). The Serbian grassroots movement “Jugo cikling kampanja” has been organizing communication-related campaigns and petitions for the development of cycling infrastructure since 1998 (Kopf, Citation2016).

In Germany, the grassroots movement “Radentscheid” was born at the local level to strengthen and institutionalize cycling (e.g. by holding city-wide referendums). “Radentscheid” originated in Berlin in 2015, fueled by the disappointment of many cycling activists about the city’s cycling policy (Schneidemesser, Citation2021). A key point for its success was the drafting of a strategic plan with specific demands for policymakers (Lüdemann & Strößenreuther, Citation2018). These included precise recommendations on expanding and improving cycling infrastructure, setting up a municipal department for cycling, and cycling-related communication campaigns (Volksentscheid Fahrrad, Citation2016a). Within a few weeks, the initiators collected more than 100,000 signaturesFootnote1 to support their demands (Becker & Sterz, Citation2021). After several months of negotiations between the “Radentscheid” and the Berlin government, and without a formal referendum, both parties agreed to the Berlin Mobility Act (Mobilitätsgesetz), which formally passed legislation in the Berlin State Parliament in 2018 (Stadt Berlin, Citation2018; Schneidemesser et al., Citation2020). Among other issues, the Berlin Mobility Act includes far-reaching expansion of the cycling infrastructure and regulatory measures, which enables the administration to support cycling more effectively (Becker & Sterz, Citation2021). Following the Berlin “Radentscheid”, the movement was established in more than 50 cities and regions in Germany (Changing Cities, Citation2022), collecting more than one million signatures by 2022 (Sørensen, Citation2022).

3. Research design

For each case study in our analyses, we combined exploratory document analyses, expert interviews, and quantitative analyses of secondary data. We gathered and analyzed official documents from the four case study cities related to cycling or the Radentscheid between 2008 and 2022 (e.g. budget reports, mobility plans, press releases). In addition, we screened crucial documents from the Radentscheid and key articles from local newspapers relating to it.

Eventually, we selected the most important documents for further analyses. These 48 documents served to reconstruct the timeline and outcome of cycling-related policies and planning in the four cities.

The expert interviews aimed to complement exploratory document analyses with in-depth and first-hand information. Furthermore, we checked with the interviewees if any important document was missing. We conducted four semi-structured interviews with the cycling officer in each city administration during the summer of 2022. Each interview took around 40 min and covered three topics: (i) the development of bicycle use in their respective city over the past 20 years; (ii) the reasons for the perceived increases in cycling in the last 20 years; and (iii) the role of the Radentscheid initiatives in local cycling policies. Two interviewees were added to provide a more complete picture of the current cycling situation: a transport researcher who is also a member of the Radentscheid initiative in Berlin, and the official responsible for strategic planning and travel demand management in Munich. After transcribing the audio-recorded interviews, we analyzed their content for similarities and differences between the cities using structured qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2023).

The quantitative analysis covered estimates of four indicators and time series for each city: (i) the modal share of cycling; (ii) the average number of cycling trips per day and person in 2002, 2008, and 2017, as reported for all four case studies in the German national travel survey Mobilität in Deutschland (MiD; infas, Citation2019); and (iii) cyclist numbers between 2017 and 2021, based on automated counting point data. It should be noted that data from Hamburg and Frankfurt rely on manual measuring points, since automated counting points were not set up until 2020 and 2022 respectively. The figures should, therefore, be compared over time rather than between cities. Finally, (iv) citizen satisfaction with local cycling conditions from 2012 to 2022 was ascertained via data from the “Fahrradklimatest” survey, conducted by the German cycling federation ADFC in all four case cities. It is worth mentioning that its sample is not representative of the entire population in a city but rather of the cyclists in a city (Syberg, Citation2021).

4. Development of local cycling policies in the case studies

4.1. Berlin

Berlin was developed as a car-oriented city for decades in its western as well as its eastern part (Pucher & Buehler, Citation2008). In 1997, the first German Critical Mass started in Berlin (Humphries, Citation2002), but it was not until 2002 that relevant investment was made for planning and implementing cycling measures (Stadt Berlin, Citation2004). A few years later, the first comprehensive cycling strategy aimed to raise the cycling share from 10% to 15% in 2010 (Stadt Berlin, Citation2005). This was the first commitment to promoting cycling in Berlin, even though the city did not achieve its target.

In 2008, the expansion of cycling infrastructure was interrupted because of budgetary constraints caused by the financial crisis and a lack of political will. Over the next few years, the perceived lack of safety and improvement angered cyclists. They channeled their dissatisfaction into the Critical Mass movement (Tagesspiegel, Citation2014, Citation2016), the Radentscheid initiative, and, ultimately, the first bicycle referendum on cycling in Germany. The referendum’s initiators collected over 105,000 signatures within a few weeks in the spring of 2016 (Volksentscheid Fahrrad, Citation2016b). The citizens’ petition was accompanied by a broad communication campaign just before the state elections in Berlin, bringing the topic into the media discourse and onto the political agenda (Lüdemann & Strößenreuther, Citation2018). After the elections and negotiations between the Radentscheid and the emerging coalition, the Berlin parliament passed an ambitious cycling law, bringing active transport to the same legislative level as motorized private transport (e.g. reform of the departments in charge of transport policies, expansion of cycling infrastructure). The new cycling plan defined a target cycling network of 2,400 km, of which 850 km are a priority network with a minimum width of 2.5 meters (Stadt Berlin, Citation2021a). In the years since, however, less than one hundred kilometers of new bikeways were built between 2017 and 2020 (Tagesspiegel, Citation2020), including 25 km of pop-up bike lanes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Stadt Berlin, Citation2021b). According to the expert interviewed, the complicated process between the state and the districts of Berlin and the lack of political will in some districts can be seen as contributing factors. Funding for the development of cycling infrastructure increased sharply from €5 million in 2017 to €35 million in 2021 (€10 per inhabitant; Stadt Berlin, Citation2022a).

4.2. Frankfurt

In 2003, the city of Frankfurt set a target to increase its cycling share from 6% to 15% by 2012 to reduce car traffic. To meet this objective, the local council proposed over 60 measures (Stadt Frankfurt am Main, Citation2004). The expert interviewed revealed that the establishment of a cycling unit in the city administration in 2009 was an important innovation to commit to the expansion of cycling infrastructure and offer services such as a website with information about cycling (Stadt Frankfurt am Main, Citation2013). In the following years, bicycle lanes were installed primarily together with planned road repair interventions. Furthermore, only minor improvements for cyclists were implemented, including the expansion of bike parking facilities (Buehler et al., Citation2021). Similar to Berlin, the growing disappointment about the lack of progress in local cycling led to the launch of the Frankfurt Radentscheid initiative in 2018. By collecting 40,000 signatures in spring 2019, a city-wide referendum was proposed. However, after rejecting the referendum for formal reasons, the city council negotiated with members of the Radentscheid and agreed on a cycling policy resolution (FNP, Citation2019). In contrast to the cycling law in Berlin, the resolution specifies the streets on which cycling infrastructure is to be built within the next five years with improved quality standards. Since 2019, most of the cycling infrastructure has already been implemented, including bike lanes on some trunk roads and the expansion of bicycle parking spaces (Radentscheid Frankfurt, Citation2022). Additionally, the funding for cycling policies rose sharply to €7 million in 2020 and €14 million (€19 per inhabitant) in 2021 (Fraktionen der CDU, SPD und Grünen, Citation2019).

4.3. Munich

In Munich, the city council did not commit to cycling improvements until it had adopted a comprehensive cycling strategy in 2009 (Landeshauptstadt München, Citation2009). With this, the city of Munich wanted to increase its share of cycling from 14% in 2008 to 18% by 2015. From 2010 to 2018, a major communications campaign for cycling, “Radlhauptstadt” (cycling capital), was launched by the city to raise awareness of cycling and motivate citizens to cycle more often, using high-profile events, advertising campaigns and merchandizing (Lanzendorf & Busch‐Geertsema, Citation2014; Tz, Citation2011). In 2017, the city appointed a cycling coordinator to oversee the promotion of cycling across departments and to act as a liaison officer between the administration, city council, residents, and the public. However, the campaign and the cycling coordinator raised expectations among Munich’s cyclists, which, according to expert interviews, could not be sustained. Consequently, in 2019, a Radentscheid campaign emerged in Munich (Landeshauptstadt München, Citation2020). It organized two citizens’ petitions for a referendum: (1) for a continuous bike lane network and safe design of intersections to make cycling “safe and comfortable”, and (2) for a 10-km cycling ring path around the old town (Radentscheid München, Citation2019). Both petitions were signed by 80,000 residents, but the city parliament had already adopted both petitions before the referendum was held (SZ, Citation2019). In addition to other schemes, measures for cycling have been funded with €25 million p.a. (€17 per inhabitant) since 2019 (SZ, Citation2020a).

4.4. Hamburg

In Hamburg the first cycling strategy was adopted in 2008 with the aim of doubling the cycling share to 18% by 2015 (Stadt Hamburg, Citation2007). Furthermore, in 2015, a coordinator for the transition to sustainable transport (“Mobilitätswende”) was established and an alliance for cycling formed across different administrative units (Stadt Hamburg, Citation2016). However, as in other cities, there was dissatisfaction with the slow pace of expanding the cycling infrastructure and the lack of safety for cyclists. So, in 2019 a local Radentscheid campaign started and a petition to initiate a city-wide referendum collected 23,000 signatures. The Hamburg city parliament approved the list of signatories and immediately started negotiations with the Radentscheid representatives. The outcome of this process was a catalogue of regulatory and communicative measures to promote bicycle traffic (Fraktionen der SPD und Grünen, Citation2020). A key objective is to improve the safety of children and older people by building bike lanes on main roads, with a structural separation from pedestrians and motorized traffic as well as cycling communication campaigns (Stadt Hamburg, Citation2022). It should be noted that the list of measures does not include commitments regarding financial resources, cycling route lengths to be built or other time-defined targets as in most other cities. However, both the expenditure for cycling and cycling infrastructure increased significantly in Hamburg in 2020 (ibid.). In 2021 and 2022, 60 km of new cycling facilities were built each year. The cycling expenses increased from €50 million in 2019 to €87 million in 2020 (ibid.).

5. Development of a three-stage model for the cycling boom and the social institutionalization of cycling in the case studies

Local cycling policies show a similar development in all four case studies over the last two decades. From our analyses in Section 4 (expert interviews, document analysis) and quantitative data (), we derived a three-stage model to understand how the cycling boom interacts with its institutionalization (): (i) Commitment, (ii) Imbalanced growth, and (iii) Institutional adaptation.

Figure 1. A three-stage model of the interaction between the cycling boom and institutionalization in large German cities.

Table 1. Bicycle use change in large German cities between 2002 and 2017Table Footnotea.

Table 2. Assessment of local cycling conditions between 2012 and 2022.

Table 3. Index of bicycle use between 2017 and 2021 by permanent bicycle counting stations.

5.1. Commitment (2000 to 2010)

During the twentieth century, cycling played a minor role in local policymaking and only gradually entered the political agenda at the beginning of the 2000s in our case study cities. For the first time, local governments committed themselves to increasing cycling levels by adopting comprehensive cycling strategies and setting specific targets for cycling modal shares. However, major investments and systematic improvements in cycling infrastructure were absent during this period (Buehler et al., Citation2021; Lanzendorf & Busch‐Geertsema, Citation2014; Pucher & Buehler, Citation2007).

Despite limited policy interventions, quantitative data from the national travel survey (infas, Citation2019) show that the number of cycling trips and the modal share increased in this stage in all case studies (), except for Hamburg, where the cycling policy was delayed by a few years (Lanzendorf & Busch‐Geertsema, Citation2014). In Hamburg, a substantial increase in cycling trips was first observed in 2017 but not as early as 2008 (data between these years is not available). The local cycling officers confirmed that the increasing popularity of cycling among citizens was not due to systemic infrastructure improvements but rather to the various social changes that have occurred in recent decades. Due to the increasing importance of trends like sustainability, health, and individualization in urban, educated settings, cycling has become an element of modern urban lifestyles. The cycling officer from Berlin referred to it as 'the current Zeitgeist’, while the one from Hamburg stated:

“Another societal issue is climate change. These are […] aspects that have led many people to cycle more, then of course health-related concerns, cost aspects and ultimately […] cycling became ever more fashionable. […] Cycling is also very strongly associated with the whole issue of quality of life and quality of stay.” [Cycling officer from Hamburg]

“Let me put it crudely: green types, sporty […] these are young, healthy, well-educated people.” [Cycling officer from Munich]

5.2. Imbalanced growth (2010 to 2018)

The imbalanced growth stage is characterized by an anchoring of cycling measures in municipalities and a stronger increase in cycling than in previous years. Between 2010 and 2018, further cycling investments were announced and partially implemented by local governments in a more coordinated way than before. Furthermore, cities started to establish administrative units for the promotion of cycling. For example, Hamburg appointed a cycling coordinator at this stage and Frankfurt set up a specific cycling unit in its administration to coordinate and implement specific cycling measures. However, despite these administrative changes, the funding and actual building of cycling infrastructure stagnated.

“And in fact, remarkably little happened in terms of infrastructure in the years from 2008 to 2017. I think that’s why the referendum came about.” [Cycling officer from Berlin]

On the contrary, the numbers of daily cyclists in the cities increased significantly. Between 2008 and 2017, the modal share of cycling continued to rise in all case studies, even at a higher rate than before (). For example, there were 50% more cyclists in Berlin and Frankfurt. Overall, bicycle use was highest in Munich, where almost one in five trips was made by bike in 2017. Moreover, the data shows that bicycle use increased considerably more in large cities than in the rest of the country between 2002 and 2017. In 2017, the number of cycling trips per person in large cities exceeded the German average by more than 50%, while these figures were almost the same in 2002.

However, despite the local government’s commitment to cycling, improvements came rather slowly. Data from the German cycling federation ADFC indicates an increasing dissatisfaction among citizens with cycling conditions in this period (). In Berlin, for example, the negative assessment of local cycling conditions climbed notably between 2012 and 2016. In Munich and Frankfurt, the negative rating reached a peak in 2018. This might be directly related to the lack of safe infrastructures, such as separated bike lanes, maintenance facilities and lighting (Echiburú et al., Citation2021; Lee, Citation2014; Sharma et al., Citation2019) as noticeable by the high number of cycling accidents (Destatis, Citation2022).

The dissatisfaction with cycling conditions eventually led to local activism, diverse forms of protests and, ultimately, the emergence of the grassroots movement Radentscheid:

“There was a reason why the [Radentscheid] was called for because simply too little had happened. That has to be said quite self-critically. Before that, we implemented a lot of micro projects, but that was completely out of proportion to the growth in cycling […], there was such a huge gap in between, so cycling is growing and growing and growing.” [Cycling officer from Hamburg]

5.3. Institutional adaption (2018 to 2022)

The third stage in our cycling boom model starts with the agreements between local governments and the different local Radentscheid initiatives. Differences between these agreements can be observed. Berlin passed an ambitious cycling law, which brings active transport to the same legislative level as motorized private transport. In Frankfurt, on the other hand, the resolution includes specific streets where cycling infrastructure should be provided with a high standard. The differences between Frankfurt and Munich, compared to Berlin and Hamburg, can be mainly attributed to the fact that the former are not city states and are, therefore, unable to pass certain forms of legislation. However, these agreements mean a turning point in the local governments’ cycling policy in at least three dimensions. First, more funds and staff are allocated to implementing cycling-related measures. In Berlin, the annual investment budget for cycling infrastructure increased from €5 million in 2017 to €32 million in 2020 (excluding personnel costs). Cycling expenditure in Hamburg is reported to be the highest, with €91 million in 2021. Furthermore, in Berlin, the city government’s personnel capacity increased from 3.5 full-time equivalents in 2016 to more than 70 in 2021 (Stadt Berlin, Citation2021b). Hamburg and Munich established new mobility departments with the ambition to contribute to the transformation of urban mobility.

Second, cities expanded their cycling infrastructure and drafted new cycling regulations. In Hamburg, 118 km of new cycle paths (2020–21) and, in Frankfurt, 34 km of bike lanes and 6,000 bicycle parking spaces have been built (2019–21). Moreover, new regulations for constructing cycling infrastructures have been defined, for example in Frankfurt a 2-meter minimum width for bike lanes, the preference for protected bike lanes, red-colored bike lanes and a clear intersection design with dedicated cycling routes. These measures, consequently, catered not only for experienced cyclists but also for those inexperienced who need secure infrastructures protected from motorized traffic.

Third, and most importantly, the new cycling policies question the hitherto sacrosanct priority of the automobile in urban transport. They include actions such as the conversion of car roads into bike lanes (Lanzendorf et al., Citation2022), a policy that seemed impossible in car-oriented Germany. According to the cycling officers interviewed, the increase in funding and newly built infrastructure can be attributed to the Radentscheid initiatives. All local cycling officers noted a turning point in cycling policies in the public debate, as well as increased awareness within the administration, as a result of the popular Radentscheid campaigns.

“It must also be said that we have received a major boost from civil society, we had a Radentscheid here and I firmly believe that this has been a very important development. […] After all, it’s actually a tremendous development and it also comes from interacting with civil society.” [Cycling officer from Hamburg]

“I think the most important thing [about the development through the Radentscheid] was simply that action happened, that things couldn’t go on as they were.” [Cycling officer from Berlin]

The above-described policy changes led to a gradual increase in cycling satisfaction, as shown by ADFC data. After the decrease in satisfaction with cycling described above, the cycling policy changes led to a gradual increase in satisfaction with cycling conditions, starting in 2018 in Berlin (). In the other cities, the assessment of cycling conditions emerged later, in parallel with the delayed developments in the respective cities. The improvement in the overall assessment is largely driven by the improved assessment of promoting cycling in recent times in all cities. The permanent bicycle counting stations offer additional evidence (), showing increased cyclist numbers in all cities since 2017, albeit only to a limited degree in Frankfurt. In Munich and Hamburg, however, the 2021 figures grew by one third compared to 2017. It is worth noting that the 2020 and 2021 cycling boom might be partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, it is not yet possible to establish strong evidence of the effect of the Radentscheid initiatives on bicycle use in the four cities.

6. Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we used document analysis, expert interviews, and quantitative data to examine the cycling boom and related policies in the cities of Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, and Frankfurt over the past decades. The results obtained reveal a similar path for all four case study cities, illustrated by a three-stage model. First, the local government commits to raising the share of cycling, an important first step (Commitment). Second, their commitment creates dissatisfaction among the citizens when cycling levels increase further, but adequate measures and funding are lacking (Imbalanced growth). Third, the Radentscheid initiatives provide a turning point to institutionalize and consolidate cycling on political agendas, setting and securing long-term planning and implementation processes for a new stage in local cycling development (Institutional adoption).

These institutional changes are a key difference from the achievements of the other cycling-related grassroots movements previously discussed. In most of those cases, initiatives were only able to trigger or implement single measures, such as individual infrastructure projects, without affecting the cycling policy process as a whole (Jensen, Citation2017; Kopf, Citation2016). Other cycling grassroots movements have not even been able to trigger any improvements. For example, Fernandez‐Heredia and Fernandez‐Sanchez (Citation2020) claim that in Madrid, despite various cycling initiatives, no changes in respective policies were achieved. The early grassroots movements in Copenhagen had an influence on the city’s highly praised cycling infrastructure (Carstensen et al., Citation2015). However, Copenhagen’s long history of cycling in urban planning has made this success possible and distinguishes it from the situation in Germany.

The main reasons for the success of the Radentscheid movements can be seen in their broad support among the population, on the one hand, and their high visibility and effective use of democratic political tools, on the other. Increased use of bicycles and positive attitudes toward cycling, as well as growing dissatisfaction with cycling-related policies, formed the basis for the initiatives and civil commitment (Schneidemesser, Citation2021; see Section 5). In this respect, Radentscheid hardly differs from other cycling grassroots movements, most of which emerged under similar conditions. However, a major difference is the reliance on signed petitions and the transfer of specific goals into politically binding laws. For example, the Critical Mass movement, which emerged several years before Radentscheid, does not pursue political goals or the implementation of specific policies (Carlsson, Citation2002). However, even other, more politically motivated initiatives, such as Londoners on Bikes, did not use the tools of democratic participation like the Radentscheid (Aldred, Citation2013). Certainly, the possibilities for citizen participation differ depending on the country or city, yet public petitions are common in most democracies (Riehm et al., Citation2014), allowing grassroots movements in other regions to bring comprehensive cycling demands to the ballot.

Furthermore, the process outlined suggests that the ongoing cycling boom in our case studies cannot be seen primarily as the result of the local administration’s engagement in cycling. On the contrary, citizens’ initiatives pressured policymakers and the administration to act. Therefore, a key finding of this study is that citizens were the essential driving force in the promotion of local cycling for two reasons. First, cycling rates increased in the stages of commitment and imbalanced growth despite only minor infrastructure improvements. The expert interviews and past research (Buehler & Pucher, Citation2021; Hudde, Citation2022) explain this cycling boom as part of ongoing social change and lifestyle choices that favor the bicycle as a fast, reliable, and inexpensive mode of urban transport. Second, from this development, both the number of activists and citizen political support increased considerably, providing a sound basis for the emerging Radentscheid grassroots movement. So, the process evolved from the bottom up rather than from the top down, implying that changes in travel behavior do not necessarily have to be brought about by political and planning decisions (Sagaris, Citation2014; Wieser, Citation2021). Rather, policymaking appears to be more reactive than proactive, contradicting assumptions that a notable increase in bicycle use seems to be triggered foremost by cycling policies (Sheldrick et al., Citation2017).

Increasing cycling rates requires an institutionalization process at the local level. On this basis, three main policy recommendations emerge.

Involve civil society in transport planning: Our results suggest that the improvement of cycling conditions is not only derived from setting the political agenda but much more from meeting citizen needs and ongoing social trends. Therefore, cycling-related policies reduced the dissatisfaction among cyclists and may even help to justify measures with lower acceptance, like the reduction of space for private vehicles (e.g. conversions of car lanes and parking for cycling; Lanzendorf et al., Citation2023). Moreover, civil society engagement might bring important benefits for at least four reasons. First, activists and grassroots movements increase political pressure on hesitant politicians in the highly contested urban transport policy arena, where local retailer organizations or residents often oppose any change in an automobile-centric city. Second, grassroots movements generate expertise, which is helpful for the improvement of cycling conditions (e.g. in Berlin where detailed plans for the cycling network came from the Radentscheid initiative; Schneidemesser et al., Citation2020). Third, citizens may directly express their concerns in a more accurate way (Aldred, Citation2012), especially if they are involved in the earlier stages of the planning process (Sagaris, Citation2014; Wieser, Citation2021). Fourth, the still ongoing advocacy of and demands from the citizens’ initiative help the local government to allocate resources to support the development of cycling.

Establish regulatory measures: Despite a general trend of growing cycling levels, only improved and safe cycling infrastructure delivers adequate conditions for all population groups (especially children and older people). The demands made in the Radentscheid significantly raised the regulatory standards for the quality of cycling infrastructure (e.g. at least 2 m-wide cycle lanes and separation from motorized traffic). This meets the safety concerns of many cyclists, especially those who had not previously used their bikes.

Implement communication measures: The Radentscheid campaigns show the importance of effective communication for the promotion of cycling. They not only collected signatures to lobby for improved cycling conditions but raised citizens’ awareness of the benefits of cycling (e.g. more sustainable environments and higher quality of life) through various communication efforts. These included workshops, public discussions, cycling demonstrations, and social media posts. These communication strategies became an important issue in daily politics, media reports, and election discourse (e.g. broader cycling paths, pop-up bike lanes, and red coloring of paths). So, a continuous and transparent communication strategy by the local authorities may increase the citizens’ support for the changes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the interview partners from the municipalities for sharing their experiences with us. Furthermore, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which has contributed to the improvement of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 In Germany, citizens can initiate referendums on their state or city level as a tool of direct democracy by securing a quorum of supporting signatures. This petition is then submitted to their city council (Geissel, Citation2009). After a legal check, the state or city council can either accept the petition or reject it. Only if accepted are all citizens of the state or city asked to participate in a referendum based on the proposal in the petition.

References

- Adam, L., Jones, T., & Brömmelstroet, M. T. (2020). Planning for cycling in the dispersed city: Establishing a hierarchy of effectiveness of municipal cycling policies. Transportation, 47(2), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-018-9878-3

- ADFC (2023). Dossier ADFC‐Fahrradklima‐Test: ADFC‐Fahrradklima‐Test 2022: Nur Metropolen werden fahrradfreundlicher. www.adfc.de/artikel/adfc-fahrradklima-test-2022-nur-metropolen-werden-fahrradfreundlicher

- Agarwal, O. P., Kumar, A., & Zimmerman, S. (2018). Emerging paradigms in urban mobility: Planning, financing and management. Elsevier.

- Albert de la Bruhèze, A. A., & Oldenziel, R. (2018). Cycling cities. In V. Kidd (Eds.), The Munich experience (Vol. 2). Foundation of the History of Technology.

- Aldred, R. (2012). Governing transport from welfare state to hollow state: The case of cycling in the UK. Transport Policy, 23, 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.05.012

- Aldred, R. (2013). Who are Londoners on bikes and what do they want? Negotiating identity and issue definition in a ‘pop‐up’ cycle campaign. Journal of Transport Geography, 30, 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.01.005

- Bahmankhah, B., Fernandes, P., & Coelho, M. C. (2019). Cycling at intersections: A multi‐objective assessment for traffic, emissions and safety. Transport, 34(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.3846/transport.2019.8946

- Batterbury, S. (2003). Environmental activism and social networks: Campaigning for bicycles and alternative transport in west London. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 590(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203256903

- Becker, S., & Sterz, A. (2021). Drei Jahre Berliner Mobilitätsgesetz: Wie der institutionelle Umbau die Berliner Verwaltung handlungsfähig für die Umsetzung macht. Internationales Verkehrswesen, 73(3), 10–16.

- Blickstein, S., & Hanson, S. (2001). Critical mass: Forging a politics of sustainable mobility in the information age. Transportation, 28(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011829701914

- Blitz, A., & Lanzendorf, M. (2020). Mobility design as a means of promoting non‐motorised travel behaviour? A literature review of concepts and findings on design functions. Journal of Transport Geography, 87, 102778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102778

- Bruno, M., Dekker, H. ‐J., & Lemos, L. L. (2021). Mobility protests in the Netherlands of the 1970s: Activism, innovation, and transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40, 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.001

- Buehler, R., & Dill, J. (2016). Bikeway networks: A review of effects on cycling. Transport Reviews, 36(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1069908

- Buehler, R., & Pucher, J. (2021). COVID‐19 impacts on cycling, 2019–2020. Transport Reviews, 41(4), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2021.1914900

- Buehler, R., Teoman, D., & Shelton, B. (2021). Promoting bicycling in car‐oriented cities: Lessons from Washington, DC and Frankfurt Am Main, Germany. Urban Science, 5(3), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5030058

- Carlsson, C. (2002). Bicycling over the rainbow. In C. Carlsson (Ed.), Critical mass: Bicycling’s defiant celebration (pp. 235–238). AK Press.

- Carstensen, T. A., & Ebert, A. ‐K. (2012). Chapter 2 cycling cultures in Northern Europe: From ‘Golden Age’ to ‘Renaissance. In J. Parkin (Ed.), Transport and sustainability. Cycling and Sustainability (pp. 23–58). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Carstensen, T. A., Olafsson, A. S., Bech, N. M., Poulsen, T. S., & Zhao, C. (2015). The spatio-temporal development of Copenhagen’s bicycle infrastructure 1912–2013. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 115(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2015.1034151

- Casello, J. M., Fraser, A., Mereu, A., & Fard, P. (2017). Enhancing cycling safety at signalized intersections: Analysis of observed behavior. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2662(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.3141/2662-07

- Changing Cities (2022). Radentscheide in Deutschland. https://changingcities.org/radentscheide/

- Costantini, N. M. (2019). Bikes and bodies: Ghost bike memorials as performances of mourning, warning, and protest. Text and Performance Quarterly, 39(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462937.2019.1576919

- Destatis (2022). Verkehrsunfälle: Zeitreihen. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Verkehrsunfaelle/_inhalt.html

- Echiburú, T., Hurtubia, R., & Muñoz, J. C. (2021). The role of perceived satisfaction and the built environment on the frequency of cycle‐commuting. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 14(1), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2021.1826

- Emanuel, M. (2019). Making a bicycle city: Infrastructure and cycling in Copenhagen since 1880. Urban History, 46(3), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963926818000573

- Ewing, R., & Cervero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment: A meta‐analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(3), 265–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944361003766766

- Fernandez‐Heredia, A., & Fernandez‐Sanchez, G. (2020). Processes of civic participation in the implementation of sustainable urban mobility systems. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 8(2), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2019.10.011

- Fishman, E. (2016). Cycling as transport. Transport Reviews, 36(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1114271

- FNP (2019). Frankfurt wird Fahrradstadt: Diese Maßnahmen werden umgesetzt. https://www.fnp.de/frankfurt/frankfurt-wird-fahrradstadt-diese-massnahmen-werden-umgesetzt-12957482.html

- Fraktionen der CDU, SPD und Grünen (2019). Fahrradstadt Frankfurt am Main, Gemeinsamer Antrag der Fraktionen von CDU, SPD und GRÜNEN zur Vorlage M 47/19. https://www.stvv.frankfurt.de/download/NR_895_2019.pdf

- Fraktionen der SPD und Grünen (2020). Einigung mit Volksinitiative: Fahrradstadt Hamburg mit mehr Power, mehr Inklusion, mehr Sicherheit. https://www.buergerschaft-hh.de/parldok/dokument/70223/einigung_mit_der_volksinitiative_radentscheid_hamburg_die_fahrradstadt_hamburg_wird_inklusiver.pdf

- Furness, Z. (2010). Critical mass rides against car culture. In J. Ilundáin‐Agurruza & M. W. Austin (Eds.), Cycling – Philosophy for everyone (pp. 134–145). Wiley‐Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444324679.ch13

- Geissel, B. (2009). How to improve the quality of democracy? Experiences with participatory innovations at the local level in Germany. German Politics and Society, 27(4), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2009.270403

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

- Goodman, A., Panter, J., Sharp, S. J., & Ogilvie, D. (2013). Effectiveness and equity impacts of town-wide cycling initiatives in England: A longitudinal, controlled natural experimental study. Social Science & Medicine, 97, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.030

- Gu, T., Kim, I., & Currie, G. (2021). The two‐wheeled renaissance in China—An empirical review of bicycle, E‐bike, and motorbike development. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 15(4), 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2020.1737277

- Handy, S. L., Boarnet, M. G., Ewing, R., & Killingsworth, R. E. (2002). How the built environment affects physical activity: Views from urban planning. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(2 Suppl), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00475-0

- Handy, S., van Wee, B., & Kroesen, M. (2014). Promoting cycling for transport: Research needs and challenges. Transport Reviews, 34(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2013.860204

- Harms, L., Bertolini, L., & Brömmelstroet, M. T. (2016). Performance of municipal cycling policies in medium‐sized cities in the Netherlands since 2000. Transport Reviews, 36(1), 134–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1059380

- Haustein, S., Koglin, T., Nielsen, T. A. S., & Svensson, Å. (2020). A comparison of cycling cultures in Stockholm and Copenhagen. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 14(4), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/15568318.2018.1547463

- Heinen, E., & Handy, S. (2021). Programs and policies promoting cycling. In R. Buehler & J. Pucher (Eds.), Cycling for sustainable cities (pp. 119–136). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11963.003.0011

- Henderson, J. M. (2013). Street fight: The politics of mobility in San Francisco. University of Massachusetts Press.

- Horton, D. (2006). Environmentalism and the bicycle. Environmental Politics, 15(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010500418712

- Hudde, A. (2022). The unequal cycling boom in Germany. Journal of Transport Geography, 98, 103244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2021.103244

- Hull, A., & O’Holleran, C. (2014). Bicycle infrastructure: Can good design encourage cycling? Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 2(1), 369–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650020.2014.955210

- Humphries, M. (2002). I am a critical mass. In C. Carlsson (Ed.), Critical mass: Bicycling’s defiant celebration (pp. 44–51). AK Press.

- infas (2019). Mobility in Germany 2017: Summary of the short report. www.mobilitaet‐indeutschland.de/pdf/MiD2017_SummaryShortReport.pdf

- Jensen, J. (2017). The role of Ciclocolectivos in realising long term cycling planning in Bogotá: A case study of Teusacatubici and Ciclopaseo de los Miércoles.

- Jones, T., & de Azevedo, L. N. (2013). Economic, social and cultural transformation and the role of the bicycle in Brazil. Journal of Transport Geography, 30, 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.02.005

- Kopf, S. (2016). Urban grassroots, anti‐politics and modernity: Bike activism in Belgrade. In K. Jacobsson (Ed.), Cities and society. Urban grassroots movements in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 99–118). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315548845

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2023). Qualitative content analysis: Methods, practice and software (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Landeshauptstadt München (2009). Radverkehr in München ‐ Grundsatzbeschluss zur Förderung des Radverkehrs in München. https://risi.muenchen.de/risi/sitzungsvorlage/detail/1662447

- Landeshauptstadt München (2020). Radentscheid und Altstadt‐Radlring. https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/radentscheid.html

- Landeshauptstadt München (n.d.). Raddauerzählstellen. https://opendata.muenchen.de/ru/pages/raddauerzaehlstellen

- Lanzendorf, M., & Busch‐Geertsema, A. (2014). The cycling boom in large German cities—Empirical evidence for successful cycling campaigns. Transport Policy, 36, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2014.07.003

- Lanzendorf, M., Baumgartner, A., & Klinner, N. (2023). Do citizens support the transformation of urban transport? Evidence for the acceptability of parking management, car lane conversion and road closures from a German case study. Transportation. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-023-10398-w

- Lanzendorf, M., Scheffler, C., Trost, L., & Werschmöller, S. (2022). Implementing bicycle‐friendly transport policies: Examining the effect of an infrastructural intervention on residents’ perceived quality of urban life in Frankfurt, Germany. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 10(4), 2476–2485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2022.10.014

- Lee, C. ‐F. (2014). An investigation of factors determining cycling experience and frequency. Tourism Geographies, 16(5), 844–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.927524

- Lüdemann, M., & Strößenreuther, H. (2018). Berlin dreht sich ‐ vom Motto um Erfolg. Warum Berlin in zehn Jahren auf Kopenhagen‐Niveau umzubauen ist und wie die Initiative Volksentscheid Fahrrad mit Deutschlands erstem Radverkehrsgesetz das hinbekommen hat. Umweltpsychologie, 22, 105–130.

- Marletto, G., & Sillig, C. (2019). Lost in mainstreaming? Agrifood and urban mobility grassroots innovations with multiple pathways and outcomes. Ecological Economics, 158, 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.019

- Marqués, R., Hernández-Herrador, V., Calvo-Salazar, M., & García-Cebrián, J. A. (2015). How infrastructure can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Seville. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2015.10.017

- Marrana, J., & Serdoura, F. (2017). Cycling policies and strategies: The case of Lisbon. International Journal of Research in Chemical, Metallurgical and Civil Engineering, 4(1), 236-242. https://doi.org/10.15242/IJRCMCE.U0917311

- Miller, S. (2019). Social institutions. In Edward N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 ed.). Springer. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/social-institutions

- Mölenberg, F. J. M., Panter, J., Burdorf, A., & Lenthe, F. J. V. (2019). A systematic review of the effect of infrastructural interventions to promote cycling: Strengthening causal inference from observational data. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0850-1

- Peters, R. (2021). Botschaften des ADFC‐Fahrradklima‐Test 2020: Was sagen uns die Ergebnisse? ADFC, https://fahrradklima-test.adfc.de/fileadmin/BV/FKT/Download-Material/Ergebnisse_2020/FKT_2020_Vortrag_Botschaften_Rebecca_Peters.pdf.

- Piatkowski, D. P., Marshall, W. E., & Krizek, K. J. (2019). Carrots versus sticks: Assessing intervention effectiveness and implementation challenges for active transport. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17715306

- Popan, C. (2019). Bicycle utopias: Imagining fast and slow cycling futures. Routledge.

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2007). At the frontiers of cycling: Policy innovations in the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany. World Transport Policy and Practice, 13, 8–57.

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2008). Cycling for everyone. Lessons from Europe. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2074(1), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.3141/2074-08

- Pucher, J., & Buehler, R. (2021). Introduction: Cycling to sustainability. In R. Buehler & J. Pucher (Eds.), Cycling for sustainable cities (pp. 1–10). The MIT Press.

- Pucher, J., Buehler, R., & Seinen, M. (2011). Bicycling renaissance in North America? An update and re‐appraisal of cycling trends and policies. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 45(6), 451–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2011.03.001

- Pucher, J., Dill, J., & Handy, S. (2010). Infrastructure, programs, and policies to increase bicycling: An international review. Preventive Medicine, 50 (Suppl), S106–S25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.028

- Radentscheid Frankfurt (2022). Status der Umsetzung. www.radentscheid‐frankfurt.de/status‐der-umsetzung

- Radentscheid München (2019). Radentscheid München fordert Vorrang für Radverkehr und Altstadt‐Radlring. www.radentscheidmuenchen.de/vorrang-fuer-radverkehr-und-altstadt-radlring/

- Riehm, U., Böhle, K., Lindner, R. (2014). Electronic petitioning and modernization of petitioning systems in Europe: Report for the Committee on Education, Research and Technology Assessment. TAB Office of Technology Assessment at the German Bundestag, Berlin. https://www.isi.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/isi/dokumente/cct/2014/Electronic‐petioning‐2014.pdf

- Ruhrort, L. (2019). Transformation im Verkehr. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28002-4

- Sagaris, L. (2014). Citizen participation for sustainable transport: The case of “Living City” in Santiago, Chile (1997–2012). Journal of Transport Geography, 41, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.08.011

- Sagaris, L., & Ortuzar, J. D. (2015). Reflections on citizen‐technical dialogue as part of cycling inclusive planning in Santiago, Chile. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2015.10.016

- Schepers, P., Helbich, M., Hagenzieker, M., Geus, B. D., Dozza, M., Agerholm, N., Niska, A., Airaksinen, N., Papon, F., Gerike, R., Bjørnskau, T., & Aldred, R. (2021). The development of cycling in European countries since 1990. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 21(2), 41–70. https://doi.org/10.18757/EJTIR.2021.21.2.5411

- Schneidemesser, D. v., Herberg, J., & Stasiak, D. (2020). Re‐claiming the responsivity gap: The co-creation of cycling policies in Berlin’s mobility law. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 8, 100270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100270

- Schneidemesser, D. v. (2021). Öffentliche Mobilität und neue Formen der Governance: Das Beispiel Volksentscheid Fahrrad. In O. Schwedes (Ed.), Öffentliche Mobilität (pp. 139–163). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32106-2_6

- Schröter, B., Hantschel, S., Koszowski, C., Buehler, R., Schepers, P., Weber, J., Wittwer, R., & Gerike, R. (2021). Guidance and practice in planning cycling facilities in Europe – An overview. Sustainability, 13(17), 9560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179560

- Sharma, B., Nam, H. K., Yan, W., & Kim, H. Y. (2019). Barriers and enabling factors affecting satisfaction and safety perception with use of bicycle roads in Seoul, South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(5), 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050773

- Sharonova, A. (2014). The cycling movement as a grassroots‐level influence on local governments: The participatory decision‐making process. Institute of Public Affairs, Warsaw. https://www.isp.org.pl/uploads/drive/oldfiles/03SharonovaFINAL.pdf.

- Sheldrick, A., Evans, J., & Schliwa, G. (2017). Policy learning and sustainable urban transitions: Mobilising Berlin’s cycling renaissance. Urban Studies, 54(12), 2739–2762. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016653889

- Sørensen, R. (2022). Es rollt wie geschmiert: Eine Million Unterschriften für die Verkehrswende. https://changing-cities.org/es-rollt-wie-geschmiert-eine-million-unterschriften-fuer-die-verkehrswende/

- Stadt Berlin (2004). Haushaltsplan für Berlin für die Haushaltsjahre 2004/2005. Senatsverwaltung für Finanzen. www.berlin.de/sen/finanzen/dokumentendownload/haushalt/haushaltsplan‐/haushaltsplan‐2004‐2005‐/hhp0405_band1bis3.pdf

- Stadt Berlin (2005). Radverkehrsstrategie für Berlin: Auf dem Weg zur FahrRadStadt. Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung. https://repository.difu.de/jspui/handle/difu/135077

- Stadt Berlin (2018). Berliner Mobilitätsgesetz (MobG BE). Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher‐ und Klimaschutz. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/verkehr/verkehrspolitik/mobilitaetsgesetz/

- Stadt Berlin (2021a). Radverkehrsplan des Landes Berlin (Radverkehrsplan Berlin – RVP). Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher‐ und Klimaschutz. www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/verkehr/verkehrsplanung/radverkehr/radverkehrsplan

- Stadt Berlin (2021b). Fortschrittsbericht 2020. Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher und Klimaschutz. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/verkehr/verkehrsplanung/radverkehr/radprojekte/radfortschrittsbericht/

- Stadt Berlin (2022a). Fortschrittsbericht 2021. Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher und Klimaschutz.

- Stadt Berlin (2022b). Radverkehrszählstellen ‐ Jahresbericht 2021. Senatsverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher‐ und Klimaschutz. https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/mobilitaet-und-verkehr/verkehrsplanung/radverkehr/weitere-radinfrastruktur/zaehlstellen-und-fahrradbarometer/

- Stadt Frankfurt am Main (2004). Gesamtverkehrsplan Frankfurt am Main: Ergebnisbericht. www.stvv.frankfurt.de/parlisobj/M_32_2005_AN1.pdf

- Stadt Frankfurt am Main (2013). Drei Jahre Meldeplattform Radverkehr. https://www.radfahren-ffm.de/264‐0‐Drei‐Jahre‐Meldeplattform‐Radverkehr.html

- Stadt Frankfurt am Main (2022). Fahrradstadt Frankfurt am Main. https://www.radfahren-ffm.de/541-0-Fahrradstadt-Frankfurt-am-Main.html

- Stadt Hamburg (2007). Radverkehrsstrategie für Hamburg. www.hamburg.de/radverkehrspolitik-hamburg/12606360/radverkehrsstrategie/

- Stadt Hamburg (2016). Bündnis für den Radverkehr ‐ Vereinbarung von 23.Juni 2016.https://www.hamburg.de/radverkehrspolitik-hamburg/5345604/buendnis-radverkehr/

- Stadt Hamburg (2022). Kurzbericht 2021 – Bündnis für den Radverkehr. Behörde für Verkehr und Mobilitätswende. https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/16008764/5c8715a225aea0a83ffc0889be804d17/data/kurzbericht-2021.pdf

- Syberg, U. (2021). Das Fahrradklima in Deutschland: ADFC‐Fahrradklima‐Test 2020. Auszeichnung Der Gewinnerstädte. https://www.adfc.de/artikel/die-siegerstaedte-des-adfc-fahrradklima-tests-2020

- SZ (2019). München bekommt bessere Radwege. Süddeutsche Zeitung München. https://sz.de/1.4537918

- SZ (2020). Was sich für Münchens Radfahrer verbessert hat ‐ und was nicht. Süddeutsche Zeitung München.https://sz.de/1.3704555

- Tagesspiegel (2014). Critical Mass in Berlin: Polizei kapituliert vor Radfahrern. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/polizei‐kapituliert‐vor‐radfahrern‐3571201.html

- Tagesspiegel (2016). Protestfahrt Critical Mass: Sitz-Demo gegen Berliner "Radfahrhölle Oranienstraße". https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/polizei-justiz/sitz-demo-gegen-berliner-radfahrholle-oranienstrasse-3745000.html

- Tagesspiegel (2020). Bittere Bilanz für Berlins Fahrradfahrer: Weniger als 100 Kilometer neue Radwege seit 2017. https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/weniger-als-100-kilometer-neue-radwege-seit-2017-7595878.html

- Timms, P., & Tight, M. (2010). Aesthetic aspects of walking and cycling. Built Environment, 36(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.36.4.487

- Turner, J. (1997). The institutional order. Longman.

- Tz (2011). Radlhauptstadt München: Ist sie das viele Geld wert? https://www.tz.de/muenchen/stadt/radlhauptstadt-muenchen-viele-geld-wert-1501065.html

- van der Kloof, A. (2015). Lessons learned through training immigrant women in the Netherlands to cycle. In P. Cox (Ed.), Cycling cultures (pp. 78–105). University of Chester Press.

- Volksentscheid Fahrrad (2016a). Hintergrundtext zum Volksentscheid Fahrrad.

- Volksentscheid Fahrrad (2016b). Volksentscheid Fahrrad stellt mit 105.425 Unterschriften Rekord auf. https://www.velobiz.de/news/volksentscheid‐fahrrad‐stellt‐mit‐105425‐unterschriftenrekord‐auf‐veloQXJ0aWNsZS8xNTMyMwbiz

- Wieser, B. (2021). Unruly users: Cycling governance in context. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 9, 100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100281

- Winters, M., Buehler, R., & Götschi, T. (2017). Policies to promote active travel: Evidence from reviews of the literature. Current Environmental Health Reports, 4(3), 278–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-017-0148-x

- Yang, L., Sahlqvist, S., McMinn, A., Griffin, S. J., & Ogilvie, D. (2010). Interventions to promote cycling: Systematic review. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 341(oct18 2), c5293–c5293. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5293

- Yang, Y., Wu, X., Zhou, P., Gou, Z., & Lu, Y. (2019). Towards a cycling‐friendly city: An updated review of the associations between built environment and cycling behaviors (2007–2017). Journal of Transport & Health, 14, 100613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100613

- Zhao, C., Carstensen, T. A., Nielsen, T. A. S., & Olafsson, A. S. (2018). Bicycle-friendly infrastructure planning in Beijing and Copenhagen – Between adapting design solutions and learning local planning cultures. Journal of Transport Geography, 68, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.03.003