Abstract

The aim of this article is to map the plurality of pluralist theories, indicate and (hopefully) make sense of what the many important contributions explaining this resurgent notion have been to date, and finally locate “covenantal pluralism” in this developing conversation. The essay plots at least 11 models on a “pluralist quadrant” in order to help us understand their unique contributions to the pluralism debate. Finally, I aim to show in conclusion how an emphasis on covenants captures some of the best of the many discourses about pluralism discussed in the essay, thereby highlighting the advantages of a holistic and balanced approach to conceptualizing normative pluralism.

“Pluralism” is a widely used yet also highly ambiguous word in contemporary public discourse. Indeed, to the non-initiate, “pluralism” is as various, contested, and confusing as the diversity to which it is a response. In popular level parlance, “pluralism” often simply means differences co-existing together in society, though how deep/wide/what kinds of difference remains unstated. It also does not signal any consensus understanding of how such difference can or should co-exist; whether it is mere tolerance, or embrace, or something else, remains open. There is furthermore often little clarity regarding which actors or contexts are called to be pluralistic—individuals? civil society? the state? all of the above? Generic “pluralism” leaves many, and perhaps the most important, questions unanswered.

Fortunately, a growing number of theorists and public intellectuals have recognized the need for more precision in our thinking about pluralism, and they have offered numerous more carefully specified pluralist theories. Among the players in the now-burgeoning marketplace of pluralisms there is “confident pluralism” (Inazu Citation2016), “courageous pluralism” (Patel Citation2020), “principled distance” (or “Indian model”) pluralism (Bhargava Citation2012), “principled pluralism” (Carlson-Thies Citation2018), “religious harmony” pluralism (Neo Citation2020), “deep pluralism” (Connolly Citation2005), “pragmatic pluralism” (Patton Citation2006), and many more.

The aim of this essay is to map this plurality of pluralist theories, indicate and (hopefully) make sense of what the many important contributions of this resurgent notion have been to date, and finally locate “covenantal pluralism” in this developing conversation.

The concept of covenantal pluralism (Stewart, Seiple, and Hoover Citation2020; Stewart Citation2018; Seiple Citation2018a, Citation2018b) was developed over the past few years at the Templeton Religion Trust, which in 2019 formally launched its Covenantal Pluralism Initiative (CPI). The “covenant” that defines this pluralism is inclusive and global. It is a holistic vision of legal equality and social solidarity for all. Going beyond banal appeals for mere “tolerance,” the philosophy of covenantal pluralism aims to specify the legal/constitutional parameters and the cultural conditions of engagement that enable societies to live constructively with deep differences.

The goal of covenantal pluralism is not to invalidate or even necessarily supplant these other pluralist theories. Each in its emphasis captures something essential about how and why to engage one another constructively through mutually respectful encounters, leveraging deep differences in the search for solutions to shared problems. But by plotting these pluralisms to help us understand what their unique contributions are to the pluralism debate, I aim to show in conclusion how an emphasis on covenants captures some of the best of the many discourses about pluralism we’ll touch on, thereby highlighting the advantages of a holistic and balanced approach to conceptualizing normative pluralism.

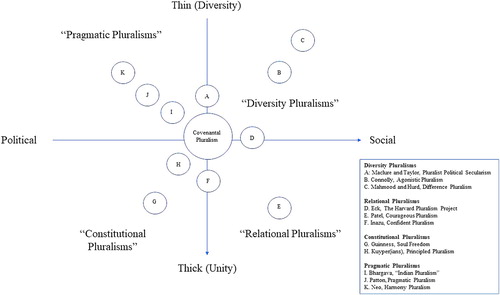

My plottingFootnote1 takes place on two axes: thin vs. thick and political vs. social, yielding 4 quadrants (see ). By thin vs. thick I mean that some traditions of pluralism take as their assumption a much thicker set of consensus or structured boundaries, within which a kind of pluralism is imagined. Thicker traditions have a larger set of ground rules. They are less willing to default on or negotiate their own foundations. Thinner pluralisms have a smaller set of ground rules, preferring to prize diversity, rather than unity, to open the widest possible pluralism—sometimes at greater risk of instability, but always concerned to ward off homogeneity or oppression. I hasten to add that “thin” does not necessarily mean weak, as though the thin commitments necessary to enable such wide, diverse pluralisms are held lightly. In fact, it is in this quadrant exactly where one may find the most dogmatic pluralists! Their commitment to wide-scale diversity is so powerful it is a nearly a priori virtue, a thin commitment perhaps, but hardly held lightly. Finally, by political vs. social pluralisms I mean to show that some traditions see the primary or essential work of pluralism as more structural or constitutional, and others see it as more civil, interreligious, grassroots. The question of “what comes first,” a pluralist politics or a pluralist civil society, is admittedly a somewhat false dilemma. Most, when pressed, would admit that both are essential.

Placing the pluralisms I’ll be discussing on a grid highlights their respective emphases, although some pluralisms may span quadrants. In what follows, I will first make explicit what is—and what is not—being addressed in this conceptual mapping. I will then discuss each quadrant in turn, what I have titled Quadrant 1: Diversity Pluralisms; Quadrant 2: Relational Pluralisms; Quadrant 3: Constitutional Pluralisms; and Quadrant 4: Pragmatic Pluralisms. Finally, once we have an organized understanding of our quadrants, I will lay out a concluding argument for what covenantal pluralism might contribute to our apparent problem of such a ponderous potpourri of pluralisms.

What Kinds of Pluralism?

It goes without saying that pluralism, even in its broadest sense, is not an uncontested or universally celebrated good. In fact, one could argue—as Charles Taylor does in A Secular Age (Citation2007)—that wide-scale aspiration to public pluralism is a relatively recent idea. It is neither the norm in human history, nor is it necessarily widely beloved even today. The accommodation, even engagement, of deep difference is regarded by some societies, political communities, and religious or ideological groups as too risky a wager, one that will undermine rather than augment certain public goods like stability, order, and growth.Footnote2 Such actors are effectively non- or even anti-pluralist. So, when we talk about pluralism, we are talking about those societies and communities that believe the presence of diversity, while at times challenging, is not something just to be lamented. Rather, a “pluralist” is one who believes that diversity, when engaged in the right spirit and under the right conditions, can have powerfully constructive effects.

It is important, then, to also say what we are not talking about. Richard Mouw and Sander Griffioen (Citation1993), for example, name at least three kinds of diversity:

“Directional” or religious/worldview diversity (deep diversity in first principles).

“Structural” diversity (societal differentiation, a school vs. a business for example).

“Cultural” diversity (unique cultural expressions, Thai vs. Mexican cuisine for example).

The 4-quadrant scheme that I am suggesting in this essay makes sense of only the first kind of diversity in Mouw & Griffioen’s taxonomy. In other words, the quadrant framework is an organized understanding of how different streams or discourses of pluralist thought propose to approach deep diversity in religions, worldviews, fundamental orientations, or “comprehensive doctrines” (Rawls Citation1993, 58). Structural and cultural diversity have their own complexities,Footnote3 but are of a different order. You work for a for-profit business, I work for a non-profit university, but so what? I prefer Thai food, you prefer Mexican cuisine, but so what? These are differences, but not deep differences, expressing preferences but without reference to mind-independent realities. You worship Allah and live a life of surrender to his teachings under the Prophet Mohammad. I worship Jesus Christ, God-made-flesh, and follow him in law-patterned obedience. These are differences that are deep, on which we stake our lives. And these are the kinds of diversity these quadrants are assessing.

Quadrant 1: Diversity Pluralisms

Diversity pluralism has as its main concern including the widest array of positions or foundations. For that reason, these pluralisms are often argued over and against thicker conceptions of pluralism, which tend to think stronger, more structured, settlements are needed to enforce the ground rules of pluralism. We might think of diversity pluralism as profoundly anti-totalitarian. It is suspicious of power, both social and political, and how it operates to repress minority being and belief. For this reason, diversity pluralism also tends to be more methodologically postmodern, if by that we mean a kind of suspicion of the settlements of modernism which tended to paper over or preclude the kind of diversity that postmodernism takes as its core motivator. These concerns emerged powerfully after the Second World War.

Not all diversity pluralism is the same. The thinner and more social it is, the more open it maintains society and persons must be to broader and deeper kinds of pluralism. This can look risky to other quadrants, which see this kind of diversity pluralism trading a kind of cosmopolitan openness for social stability. “A free society,” Talal Asad quotes Charles Taylor, “has to substitute for despotic enforcement a certain degree of self-enforcement. Where this fails, the system is in danger” (Asad Citation2003, 3). But diversity pluralism is less invested in the question of boundaries and stability, and more invested in concerns of hospitality and diversity (Seligman, Wasserfall, and Montgomery Citation2016).

The further diversity pluralism moves to the social pole, the more skeptical it is of structured, especially state, power to resolve the basic dilemmas of pluralism. The further diversity pluralism moves to the thin pole, the fewer boundaries, and the more diversity, it is willing to admit. Overall, then, diversity pluralism also tends to be skeptical of the tradition of Rawlsian liberalism, which can sometimes see pluralism as only a problem to be overcome.

William Connolly and Agonistic Pluralism

William Connolly’s agonistic pluralism (or “deep pluralism”), for example, takes diversity as a necessarily persisting feature, not a bug, of political life. Contrary to pluralist models that might talk about negotiating pluralism as an irregular or even one-time occurrence, after which rules and boundaries are established which limit and enable certain kinds of pluralism, agonistic pluralism argues that “difference is to be celebrated because it lies at the very heart of the way the world is and the way our identities are constituted” (Deede Johnson Citation2007, 3). Neither is liberal tolerance enough, predicated as it is on a sometimes disapproval rather than embrace of difference. Room must be left for creative encounter, for what Connolly calls “the politics of becoming” (Connolly Citation2005).

It is therefore not possible to keep deep difference out of our public life and trying to do so for the false promise of unity is a form of repression. Writes Connolly (Citation2005, 41), “a pluralist is one who prizes cultural diversity … and is ready to join others in militant action, when necessary, to support pluralism against counterdrives of Unitarianism.” Says Kristen Deede Johnson (Citation2007, 3),

Unity cannot, according to these agonistic or post-Nietzschean political theorists, be the goal, nor tolerance the way to get there. Instead, these theorists search for a way to move beyond tolerance and unity to a deeper and richer embrace of difference. For the sake of diversity, they relinquish the hope of unity.

Yet while agonistic pluralism undoubtedly prizes difference, it is hardly cultural relativism. Argues Connolly, “pluralism is not the same as cultural relativism, absolute tolerance, or the abandonment of all standards” (Connolly Citation2005). Such relativism tends to embrace the majoritarian sentiments of a home culture, and pluralism advocates just the opposite: an anti-majoritarian, anti-exclusionary, anti-unitarian society. In setting wide rules for diversity, some social forms must be excluded, particularly what on our axes would be the thicker or more structured forms of pluralism (or more pointedly anti-pluralist arguments, not represented on the quadrants at all).

Finally, it should be emphasized that agonistic pluralism is skeptical of all thick forms, both religious and secular. Writes Connolly in Why I Am Not A Secularist (Citation1999, 5),

… the secular wish to contain religious and irreligious passions within private life helps to engender the immodest conceptions of public life peddled by so many secularists. The need today is to cultivate a public ethos of engagement in which a wider variety of perspectives than heretofore acknowledged inform and restrain one another.

Saba Mahmood, Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, and Religious Difference

Diversity pluralism often also has skepticism about religious freedom language and practice, as a kind of Trojan horse for state-supported religion against minority, non-supported religious or non-religious practice. Both Saba Mahmood (Citation2016) and Elizabeth Shakman Hurd (Citation2015) have been strong critics of state-based language around freedom of religion or belief for this reason.

Mahmood, an anthropologist, is especially interested in the lived, social practices of religion under Egyptian society and its unique constellations of the religious and the secular. Part of the problem, she argues, is that against the backdrop of our debates over pluralism is the intrinsic project of sovereignty and secularity. In Egypt she says, modern secular governance has “contributed to the exacerbation of religious tensions … hardening interfaith boundaries and polarizing religious differences” (Mahmood Citation2016, 1). In other words, the kind of engagement that Connolly calls for is precisely what the backdrop of secular sovereignty precludes. Rather than a deep engagement with diversity and difference, the politics of pluralism under conditions of state sovereignty ensure polarization.

Elizabeth Shakman Hurd goes so far as to suggest that states dispense with pluralistic projects altogether, arguing that they do more harm than good. If pluralism is the goal, then states, whose national interests mean that they simply cannot serve as disinterested bystanders, will necessarily shape it toward their practical goals. Sovereignty holds a necessary unity, and that kind of unity is just the sort of thing that diversity pluralism resists in the name of hospitality and difference. There is, in other words, a contradiction between structured, thick pluralisms, and the intended goals of pluralism itself, argues Hurd. We end up with a “good religion/bad religion” complex, in which the kinds of beliefs and practices that support state sovereignty are singled out for support and minority protection, whereas the ones that do not share the state’s goals or boundaries are unrecognized or even repressed. “There are no religions with clean boundaries and neat orthodoxies that are waiting on the sidelines to be engaged or reformed, condemned or celebrated,” writes Hurd (Citation2015, 121). Yet states, with their by-definition monopoly on coercive force, are usually understood to be the guarantors, not destroyers, of pluralism. Not so, argue Hurd and Mahmood. States and their sovereign powers should stay as far away from “making pluralism” as possible, tending toward a kind of libertarian pluralism, as thin and social as our quadrant allows, without simply reverting to a kind of relativistic realism.

Maclure and Taylor, Pluralist Political Secularism

Jocelyn Maclure and Charles Taylor (Citation2011) have articulated an approach they call (somewhat confusingly) pluralist political secularism. Taylor’s aim is in part to rehabilitate the term secularism: “We think that secularism has to do with the relation of the state and religion; whereas in fact it has to do with the (correct) response of the democratic state to diversity” (Taylor Citation2011, 36). But its goals are more practical than those so far covered: to imagine a “democratic state which is neutral or impartial to its relations with different faiths … which must, in other words, be neutral in relation to different worldviews and conceptions of the good—secular, spiritual, and religious—with which citizens identify” (Maclure and Taylor Citation2011, 9–10). Maclure and Taylor, therefore, take for granted certain problems of sovereignty that Hurd and Mahmood might reject. They call these the constitutive values of liberal and democratic systems, which provided systems with their “foundations and aims.” These include certain core principles like human dignity, basic human rights, and democratic political systems (Maclure and Taylor, 11).

Maclure and Taylor talk a great deal more about limits than Connolly or Hurd or Mahmood would, about unity than simply diversity, and indeed about the structures and systems (political ones among them) that enable their secular pluralism. They write that these values may not be “neutral” in some absolute sense, but they are “legitimate, because it is they that allow citizens espousing different conceptions of the good to live together in peace” (Maclure and Taylor, 11). Hearing echoes of Jacques Maritain or even Abraham Kuyper, they argue that “the challenge of contemporary societies is to ensure that everyone comes to see the basic principles of political association as legitimate, based on his or her own perspective” (Maclure and Taylor, 12). The state is agnostic, then, on how people reach these thin, broad principles, but it is not agnostic that they must reach them. It may, in fact, be called upon to coercively defend those principles.

Pluralist political secularism has, in Maclure and Taylor’s mind, various possible manifestations. They prefer to talk about “regimes of secularism,” making clear there are multiple historical, cultural, and political reasons that some societies might practice pluralism differently. Examples of history are probably the least polarizing. Here Maclure and Taylor argue that it is not unreasonable that an historically Christian society, like their own province of Quebec, might—for historic reasons—have public holidays coincide with Christian holidays, like Christmas. Quebec could hardly be expected to add every religious holiday for every citizen to its public calendar. Here is a real historic limit on pluralism. Yet, a kind of reasonable accommodation should be sought, which might mean public celebrations are limited by historical realities, but private citizens should be offered exemptions from their work or schooling for reasons of their own religious holidays. Contemporary societies must “develop the ethical and political knowledge” that will allow this management of moral, spiritual, and cultural diversity, and to build bonds of solidarity (Taylor Citation2010, 8). Pluralist political secularism supported by such solidarity, they argue, is the best system to promote diversity (Taylor and Maclure, 110).

Quadrant 2: Relational Pluralisms

Our second quadrant is defined by being primarily, though not usually exclusively, social. This is the quadrant in which we find most approaches we might call interfaith. Interfaith efforts rarely rise to the level of political or constitutional projects. Structural elements, if they exist at all, usually exist as terms for the debate or conversation. There is often a low expectation that new structural or institutional arrangements will result from the practice of relational pluralism. But the core strength of this quadrant is just that: relationships. It draws our attention to the important fact that there is no system, and no institutional arrangement, no matter how thick or coerced, that can ultimately power pluralism. A pluralist society, deserving of the title, depends on consent, and it depends on trust. Absent this, the other quadrants collapse.

So, the easy criticisms that are sometimes made of relational pluralism, the cui bono questions about what will practically result, may at times miss the point. The point is to cultivate the currency on which any political arrangement depends, trust. It also requires “self-knowledge” which can be hard won (Goodman Citation2014). And in so building social and relational capital, it culturally “funds” the arrangements which other quadrants take as their more general purpose.

Unlike our first quadrant, however, the point is rarely to suspend the thick commitments that pluralists come with. Len Goodman (Citation2014, 193) writes, “one can respect differences without abandoning one’s own commitments.” Self-knowledge, or what Rowan Williams calls comparative theology, is important here. Writes Williams (Citation2012, 132), “the comparative theologian seeks to enter into the world of the believer in another faith, to experience some of what they experience as genuine and personal spiritual discipline and means of discovery and growth, and so to understand more fully the relation between basic narratives and daily practice.” (See also Keller and Inazu Citation2020.) Yet, he quickly adds, “to say this is not to abandon the claim that there is still one narrative that offers the comprehensive perspective in which others may most truthfully and rightly be read.” The degree to which a claim to “meta-narrative” persists dictates where our relational pluralisms fall on the thin/thick axis.

Diana Eck and the Harvard Pluralism Project

The Harvard Pluralism Project helpfully underscores the distinction between diversity and pluralism. Diversity as a kind of social fact can exist, they argue, without a meaningful pluralism. There are any number of ways to deal with diversity, from exclusion to assimilation, none of which would fall on a pluralist quadrant. Pluralism argues that we can and should live together, not out of a desire for mere tolerance or even social peace, but out of a shared conviction that such diversity is not necessarily a problem to be overcome but can be a good thing (Eck Citation2015). This is the first of the project’s principles.

Such a basic confession, and it is an important if generally preferred confession, implies that engaging with our differences, learning about them, without an attempt to build consensus around a “lowest common denominator,” but simply to bring our full commitments to dialogue, is also good. It is a process that can build bonds of trust and relationship (Eck Citation2020).

Interestingly, the Harvard Pluralism Project takes as part and parcel of its social process certain structural forms. Its aims are not to reproduce or change those political forms, but it explicitly draws on the American constitutional arrangement that there should be “no establishment” of religion and that there should be “free exercise” of religion. E Pluribus Unum they argue is clearly not about establishing a common faith, but rather bringing the full weight of our convictions into society and forming bonds of mutual trust around civil dialogue. So, the Project is in search of what it calls “tables” in American society, places where “we” can face the complexity of diversity without fear, with the goal of accommodating diversity.

Eboo Patel and Courageous Pluralism

Eboo Patel’s Courageous Pluralism is at the heart of the relational pluralism quadrant, focused on building relationships, with the thickness of those commitments, fueled by a virtuous courage to share together what can seem, at times, troubling or even frightening. Patel’s practical sociological work takes form in both his scholarship and actual cases. His work building religious pluralism with the Interfaith Youth Core emphasizes three specific methods (Patel and Meyer Citation2010): storytelling, shared values, and service learning. In the first place, Patel and Meyer want to make clear that interfaith work left to theologians and religious experts can often produce a stilted or even plainly wrong report on diversity. If conversations around American evangelicalism, for example, have proved anything it is surely that the perspectives of elite religious leaders, theologians, pastors, authors (etc.), is sometimes a minority (Noll, Bebbington, and Marsden Citation2019). Patel and Meyer make clear that young people sharing their own stories, finding their own shared values, tends to build the most resilient relationships and to sustain trust in the longer haul. Putting those values to work is the final, crucial, step in cementing those bonds.

Pluralism for Patel is an ethic with three parts: respect for difference, relationships between communities of difference, and commitments to the common good (Patel Citation2018, 20; Patel Citation2016). This pluralism requires the virtue of courage, argues Mary Ellen Giess, precisely because American polarization has produced high ghettoized boundaries to dialogue and relationship (Geiss Citation2020). The gamble here is that structured, diverse encounters will build more resilience in relationships. And the case studies seem to support it. Far from a kind of drive-by-pluralism, where superficial encounters tend to sustain or enlarge existing gulfs, courageous pluralism and its pilot projects at the Interfaith Youth Core seem to show that meaningful, relationship-building encounters with diversity are a necessary catalyst for any pluralist society.

John Inazu and Confident Pluralism

John Inazu’s Confident Pluralism, like Patel’s, examines only the American context. Yet, Inazu’s pluralism is among the more difficult to plot. Inazu’s signature contribution could be described as brilliant balance between the social and political spectrum. A constitutional and political expert, Inazu nonetheless devotes nearly half of his key text, Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference, to the kind of soft, civic practices that political scientists tend to overlook: tolerance, humility, patience, practical suggestions on speech, strikes, boycotts, and even the ever-elusive common ground (Inazu Citation2016).

Inazu’s constructive criticisms of courageous pluralism are instructive here. First, he argues that Patel is “too optimistic about what we as citizens of this country [America] hold in common with one another.” Second, he says, “he neglects the current shortcomings of the legal protections that we need in order to live together in spite of our difference” (Inazu Citation2018, 133). Inazu is, as we might expect from a political scientist, skeptical about the increasingly troubled legal and political context that Patel takes for granted, and unconvinced that the quality of the commonness Patel’s courageous pluralism offers is enough to sustain American liberal democracy.

While Inazu shares with Patel a hope for a “modest unity,” Inazu argues that Patel’s unity, predicated as it is on sometimes ominous invocations of America’s Judeo-Christian past, an open minded civil religious discourse, runs a bad risk of sacralizing the state. In other words, by baptizing the American project as the sacred core which enables pluralism, the radicality of Patel’s pluralism may be undercut. Mahmood and Hurd would certainly agree.

Therein lies the challenge of finding commonness. Unlike diversity pluralism, a real and persistent anxiety in Quadrants 2 and 3 is whether and how unity can be achieved. Inazu argues that finding such ground will require both constitutional commitments and relational commitments. “We must alter the course of our legal framework for confident pluralism to be a sustainable possibility,” Inazu argues in the first part of Confident Pluralism (Inazu Citation2016, 125). A civic pluralism which makes use of these protections will still “hinge on the aspirations of tolerance, humility, and patience” (Inazu Citation2016, 128), and must include renewed practices of public speech, collective action, and a pragmatic search for common ground. To these Inazu adds a final virtue, hope.

His aspirations make Confident Pluralism difficult to plot on the thick/thin axis because, in some respects, he leaves open whether and how the United States will find that new consensus. Adjacent projects, like Yuval Levin’s Time to Build (Citation2020) offer more prescription, but again are particularly American. Nevertheless, presuming a starting point of American constitutional and social order, and privileging, as he does, the need for unity against fragmentation, Inazu finds a “thicker” home between our second and third quadrants.

Quadrant 3: Constitutional Pluralisms

Our third quadrant I have titled Constitutional Pluralisms, partly for its characteristically political emphases but also because it tends to foreground concerns for unity which, it argues, enables the kind of diversity we might reasonably call pluralistic. Pluralism, argues Quadrant 3, presumes a priori limits (among them that a kind of pluralism is good). It rejects the idea that there can be any “neutrality” (in the radically relativistic sense) when it comes to public life, and embraces that certain kinds of principles or constitutional limits will be necessary, and that those limits will shape the kind pluralism that we want, even if those limits may be open to change or revision from time to time. Importantly, although some in the upper right of Quadrant 1 might see these traditions as hardly pluralistic at all, the goal of Quadrant 3 remains the same: a diverse and pluralistic society, but one which has a coherent unity which protects and sustains that diversity. Unsurprisingly, it is in this quadrant that we tend to find many political scientists whose concerns often run more structural and systemic. It is also where we might find more classically “liberal” thinkers, or those aligned with the basic tenets of a liberal framework. Therefore, here we also find traditional advocates of freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), both because of its emphasis on political/legal structures, and its recognition of a certain thickness to those structures to provide coherence (Farr Citation2008).

Os Guinness and the Global Public Square

In The Global Public Square Os Guinness (Citation2013, 25–26) closes each chapter with a kind of liturgical refrain:

It is time, and past time, to ponder the question. What does it say of us and our times that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights could not be passed today? And what does it say of the future of freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and belief if it can be neglected and threatened even in the United States, where it once developed most fully—that it can be endangered anywhere? Who will step forward now to champion the cause of freedom for the good of all and for the future of humanity?

Several of our authors covered in this essay are concerned primarily with the United States of America, and Guinness is certainly concerned for America, but his primary goal is revitalizing a “civil and cosmopolitan global public square” (Guinness Citation2013, 180–192 emphasis added). What he offers in conclusion, “The Global Charter of Conscience: A Global Covenant Concerning Faiths and Freedom of Conscience” (Guinness Citation2013, 215–227) is an attempted refresh of Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). It is intended not as a top-down political project, but as a set of consensus principles which can draw the broadest global support among those of many faiths and none, to recommit to a kind of global constitution of the rights of conscience. The UDHR is a model of choice in this quadrant, and for Guinness, in part because it sets definite principled limits on pluralism, but it does so while admitting the widest possible rationale, religious and otherwise, for why those limits are reasonable. This gets close to what political theorist Paul Brink (Citation2012) calls “Politics without Scripts,” a vision of a pluralistic politics in which religion and liberalism have both been disestablished.

Abraham Kuyper and Principled Pluralism

Pluralism has been the special project of a minor movement in Calvinist Christianity sometimes called neo-Calvinism, an interpretation of Calvin’s social and political thought articulated through Abraham Kuyper and his heirs. For that reason, under Kuyper’s politics of principled pluralism we find many, many examples of how to assess both the “dissatisfactions—and blessings!” of civic pluralism (Carlson-Thies Citation2018).

Most prominently in the American setting, the founder and long-serving President of the Center for Public Justice James W. Skillen argues in Recharging the American Experiment: Principled Pluralism for Genuine Civic Community (Skillen Citation1994) that a key catalyst for political renewal is the inclusion of a wide array, religious and nonreligious, of voices. Herein lies some of the promise of Inazu’s modest unity, what Stanley Carlson-Thies calls “proximate pluralism” (Carlson-Thies Citation2018): a principled consensus on boundaries, which may nonetheless still produce civil pluralisms some of us think are bad or wrong. George Marsden (Citation2015) calls this approach “inclusive pluralism,” to which he adds a spin of structural differentiation, arguing that not only should citizens be free to articulate their own, internal, rationale for supporting pluralistic principles, but that organizations and institutions—educational ones among them—may also do so. Such societal differentiation threatens to take us off the confessional pluralist track this essay promised to stay on, but it’s important to emphasize—as David Koyzis (Citation2019, 235–249) does—that these concepts are necessarily related in Calvinistic thought: God, who is sovereign, cannot tolerate princes or political powers seizing his throne. Differentiation and pluralism are the logical outcomes of what Kuyper called sovereignty in its own sphere (Joustra and Joustra forthcoming).

Matthew Kaemingk (Citation2018) emphasizes the space this pluralism opens for hospitality, highlighting the sometimes underappreciated relational and social sources of Kuyper’s principled pluralism. This certainly reflects my own argument (Joustra Citation2018, 87) that principled pluralism “advances an overlapping consensus of strong public principles, without monopolizing the public logic, religious or otherwise, by which actors articulate their support for those principles.” This emphasizes that such pluralism is both (a) a process, not a reified, unyielding construct; and (b) that “pluralism is, by definition, an action verb” (Joustra Citation2018, 87). As Jonathan Chaplin (Citation2016) argues, the diversity state cannot legislate the virtues (or communities) on which it depends. A “recharge,” as James Skillen (Citation1994) would say, is necessary, from generation to generation.

The complaint against this quadrant is usually that it has given up on neutrality. And it has. As Jonathan Chaplin (Citation2006) argues in “Rejecting Neutrality, Respecting Diversity: From ‘Liberal Pluralism’ to ‘Christian Pluralism’,” there is no such fiction as an absolutely “neutral” ground from which to build these principles that enable deep religious diversity. There is no such thing, he says, as pluralism simpliciter but rather a plurality of pluralisms, each expressing a definite political perspective. Diversity is always prescribed. Therein lie real limits, and therein lies the project of pluralism.

Quadrant 4: Pragmatic Pluralisms

Our final quadrant adds something fundamental to the conversation on pluralism that has so far been implied but hardly named explicitly: namely, that there are some practical, common objectives that human beings, regardless of how deep their pluralisms run, share. This is the occasional insight that evolutionary psychology brings to these pluralism debates. Per Maslow’s (in)famous hierarchy, the bottom of the pyramid—physiological and safety needs—are not meaningfully changed by the ultimate claims one holds. Buddhists, like Christians, like atheists, need clean air, drinking water, nutrition, sleep, security, medicine, and so on. These are, in the language of Laurie Patton (Citation2006) which I have adopted for this quadrant, pragmatic considerations on which productive relationships might be built. We may have intractable moral disputes on when life begins but we can mostly agree that our sewer lines need to be in good repair, and our drinking water must be safe. Why not start small, the old adage goes, and build confidence and trust on practical matters before—or if ever—tackling major areas of variance?

This quadrant is therefore political and thin. It is structured because it is usually concerned with practical outcomes, sometimes for very specific institutions (like the university) or projects (like municipal infrastructure). It wants to manage supply lines and keep people healthy. It is functionalist in this sense.Footnote4 It is thin because its aims are not often to establish wide-scale, or thicker, agreement. Those disputes are punted in this quadrant in favor of focusing on the tangible goods that can be achieved through more limited cooperation. The hope is that such an effort might lead to broader areas of collaboration, but that is not a necessary consequence of the model.

I have also come to think of this quadrant as pandemic pluralism. Pandemics, as the Covid-19 pathogen proved, require practical alignment across a diversity of interests. The good being sought is limited, but that does not necessarily mean the resources are. The pandemic witnessed some pragmatic pluralism, where deep diversity was shelved for the moment, to attend to the crisis of the pandemic. But we also saw the limits of pandemic pluralism, where deep diversity will not be shelved forever, and in some cases where attempts to paper it over through muscular, pragmatic effort have led to culture war fissures opening in new ways. Moments of crisis can lead to a new discovery of practical partnership, but they can also expose fractures now so profound that practical, collective response is rendered nearly impossible. “Pragmaticism” depends on some widely shared social values and more than a little agreement on what constitutes “common sense.” Like John Inazu argues, we may be witnessing the limits of even those seemingly mundane alignments.

Rajeev Bhargava’s “Indian Secularism”

Rajeev Bhargava’s “Indian secularism” argues, like Kuyperian pluralism, that there is really no model of managing diversity that is ultimately neutral. What he calls “principled distance” entails “a flexible approach to the question of inclusion or exclusion of religion and the engagement or disengagement with the state.” It accepts, he says, “a disconnection between state and religion at the level of ends and institutions but does not make a fetish of it at the … level of policy and law” (Bhargava Citation2011, 105). Religious values, therefore, will inevitably play some role in shaping lawmakers and policy deciders, and far better to acknowledge and leverage the best of those values in the service of secular pluralism than suppress and obscure them in a false attempt to be free from religion. Bhargava’s model orbits closely around what we call covenantal pluralism in part because its robust engagement with religion fuels its commitment to pluralism. Bhargava lays out seven principles of his “Indian model” which plot him more clearly (Bhargava Citation2012, 77).

Multiple religions are not extras, but part of the starting point.

It is not opposed to public religion.

It is committed to multiple values, both liberty and equality, autonomy and toleration.

There is no wall of separation, as in the American sense, between state and religion. The boundaries are porous.

It exposes the false binary between active hostility and passive indifference. One can be hostile toward beliefs, but still have active respect.

There is no fixed commitment between individual or community values, or rigid boundaries between private and public.

The ideal is therefore contextual, depending on ethically sensitive, politically negotiated arrangements, not on abstract or ideological expectations.

There is much to admire in this pragmatic arrangement, which proceeds—as Bhargava argues—on the basis of India’s own history and current affairs. It responds gently to some of the concerns from the Asian world about the loss of community rights in so many Western models of pluralism, while attempting to maintain a thin, highly flexible pluralism which can respond more dynamically to the local realities of a highly diverse country like India.

The model may run idealized, especially since the rise of the BJP, where aspirations like localized flexibility have resulted in abuses, even breakages, of the diversity that Bhargava prizes. Indeed, critics might complain its thinness runs too risky in a polity that is so diverse, and sometimes violently divided. But Bhargava does contribute several crucial ballasts to the debate, including a caution for too much abstraction in pluralism, either as “individualization” or as “essentialism” or generalization of some communities or religious perspectives. His model is thin and more constitutional, Bhargava might argue, because these balances are necessary for the context of his model, where social engagement can be unnecessarily perilous, and thick consensus is both impractical and unwanted.

Laurie Patton and Pragmatic Pluralism

Laure Patton’s main premise for pragmatic pluralism is proximity. The guarantee of connectedness made possible by modern technologies and sustained by a networked global economy and urban elite means that citizens of different states no longer have the luxury of distance they once enjoyed. She writes, “there are no more distant strangers” (Patton Citation2006).

Under such conditions of immanent proximity, words like tolerance and dialogue seem archaic, certainly insufficient for the nearness we experience. We are not simply curious about each other. We do not merely tolerate each other. We need each other. Perhaps most persuasively, the scope of our problems, pandemics, climate change, ocean acidification, are now so global there is no prospect that a single state, a single religion, a single worldview, could meaningfully redress them. The problem of collective action, as social science has put it, has become the opportunity for pragmatic pluralism. We must act, and so that will drive us together. Writes Patton (Citation2006),

Situations of pragmatic pluralism are frequently ones of loss and disaster, but they need not be. They can be any situation where the perceived human value is communicated through, yet transcends, a religious tradition. They are focused on logistics and not talk: the making of music, the maintenance of bricks and mortar, the proper treatment of the dead. They create a connection among strangers that lasts longer than an episodic conversation.

Jaclyn Neo’s Harmony Pluralism

Jaclyn Neo’s “harmony pluralism” is probably the clearest on the need for a political settlement to unambiguously name pluralism as a good, and to structure that good into law and policy. As we have seen, Neo is hardly alone in recognizing the need for substantial public and legal catalysts to enable and protect a kind of pluralism. Her model of Singapore is instructive.

Singapore is a much more regulated society than many of the others that have served as context so far in this article, America, India, France, or others. For that reason, the use of the term harmony can strike the casual observer as concerning if not dangerous. Neo cites Nader’s critique of harmony at length, where she argues it “serves as a rhetorical tool for state control and coercion” (Neo Citation2020, 5). In contrast to Rajeev Bhargava, who sees constitutional rules setting grounds for a religious pluralism that may be anything but harmonious, Neo argues that such harmony—within constraints—can and should be a goal of a government. She names four such constraints: (1) rejection of any single religious group dominating; (2) a commitment to equal access to citizenship; (3) the right of religious freedom, even if not fundamental; and (4) protection of religious freedom as part of its protection of the public good (Neo Citation2017). In Neo’s model, it is the government’s obligation to weigh the demands, the risks, the costs and benefits, of religious pluralism against other needs, and so “regulate” a harmony which enables other social and political goods.

Neo says this harmony has three basic characteristics. It is correlative, contextual, and communitarian. Correlation places religious groups in a position of mutual reliance, and mutual respect. Contextuality retains the flexibility, so prized by pragmatic pluralists, to balance needs and views in respect to other social goods, and to particular localities. Finally, it is communitarian in that it prizes stable relationships and social bonds, rather than fractious individual entitlements (Neo Citation2020, 8–9).

Neo’s emphasis on harmony is reminiscent of other East Asian public philosophies, such as some accounts of pluralist Confucianism. In Confucian Perfectionism, for example, Joseph Chan argues that an emphasis on communal virtue and social harmony helps preclude the misuse of freedoms that sometimes lead to dangerous disruption in Western contexts (Chan Citation2014, 197). His account includes an enviable emphasis on both a thick political (top-down), but also a necessary social (bottom-up) harmony. Yet even here the argument is that pluralism is good, but only insofar as it serves the larger administrative goals of the state.

The fascinating plotting of harmony pluralism is that it is both thin, in that it demands very little of religious specificity from its adherents, but it is also leans heavy politically, where substantial bodies of law and regulatory enforcement are deemed necessary and helpful to catalyze and curb this public good. The risk of harmony pluralism, as Neo (Citation2020) points out at length, is that the edges of tolerable diversity can run very sharp in powerfully centralized states, where “any belief and practice is allowed” (highly diverse) but only provided it does not violate the harmony of public order.

Conclusion: Situating Covenantal Pluralism

What have we learned from this comparative plotting of pluralisms? Several conclusions stand out.

First, there is a perennial and perhaps ultimately irresolvable tension between the thinness (diversity) and thickness (unity) of certain pluralisms. This tension is not resolvable in the abstract, but only in concrete societies, with their histories, cultures, and stories in tow. The underlying question that must be answered before the problem of unity vs. diversity can be negotiated is unity and diversity for what (cui bono)? What are the virtues around which a common life should and can be gathered? What level of coherence is necessary for the kind of society we want to achieve? Of course, in many respects, an intelligible answer to this question would implicitly present a kind of unity of aims making such plotting redundant. The answer in Quadrant 1 is that diversity itself is such a chief aim, but this is in fact a minority position as we can see. Most other pluralisms would provide for equal or even higher aims than the sheer fact of diversity.

Second, if there is more consensus around a necessary if modest unity, there is less so on who is primarily responsible for cultivating and stewarding this modest unity. In other words, the goal is one most reasonable pluralists agree upon, but how to achieve that goal is not an incidental problem. Coercion is certainly one way to achieve unity, and most pluralists in our quadrants agree that state coercion is not entirely out of bounds (though some are more enthusiastic than others about this). But generally, the coercion of power is the exception, not the rule; it is the failure of underlying bonds of social trust, which require renewal on a regular, persistent basis. Such bonds can hardly be legislated into existence, and yet neither can grassroots pluralisms take root apart from the context of good laws and just boundaries. The seed of relational pluralism depends on the soil of constitutional pluralism, just as surely as the fallow soil of constitutional pluralism without the fresh seeds of social trust is a dead reed, destined not to bend and grow, but in its fragility simply to break.

What can covenantal pluralism offer us amidst these pluralisms? As Stewart, Seiple, and Hoover (Citation2020) explain:

The concept of covenantal pluralism is simultaneously about “top-down” legal parameters and “bottom-up” cultural norms and practices. A world of covenantal pluralism is characterized both by a constitutional order of equal rights and responsibilities and by a culture of reciprocal commitment to engaging, respecting, and protecting the other, albeit without necessarily conceding equal veracity or moral equivalence to the beliefs and behaviors of others. The envisioned end-state is neither a thin-soup ecumenism nor vague syncretism, but rather a positive, practical, non-relativistic pluralism. It is a paradigm of civic fairness and human solidarity, a covenant of global neighborliness that is intended to bend but not break under the pressure of diversity.

freedom of religion and belief (defined capaciously so as to include both free-exercise/freedom of conscience and also equal treatment of religions/worldviews);

religious literacy (religious knowledge of self and other that is oriented to practical cross-cultural application); and

the embodiment and expression of particular virtues—such as humility, empathy, patience, and often courage—that nourish and sustain robust pluralism.

Could such covenantal pluralism occupy just this kind of middle ground in the intellectual terrain? It hardly invalidates or supplants extant pluralist theories, but it does draw from each of the conceptual dimensions we have plotted (constitutionalism, relational solidarity, pragmatism, deep diversity). It aims to avoid problematic extremes in any direction and add distinctive and timely value to the pluralism debate. By plotting these pluralisms to help us understand what their unique contributions are, I hope to have shown that covenants can capture, integrate, and elevate some of the best of the many good traditions here. The word “covenant” is fittingly multi-dimensional in its usages and connotations. It can indicate formal commitments (e.g. a human rights treaty like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Liberties, Article 18 of which protects freedom of religion and belief). But in other contexts “covenant” can indicate informal yet no less significant (indeed, perhaps more significant) relational commitments. Covenants root in relational necessity, build trust, and operate according to a mutual pledge to respect and protect each other. Covenants are negotiated, in situ, not abstractions imposed, but relationships rendered in inscribed fidelity, not tolerance where necessary, but mutual respect enabling a society.

A pluralism that is up to the global challenges of our day must be driven by and renewed by strong social bonds, by clear expectations and boundaries, by practical puzzles, and by diverse self-aware others covenanting, as a continuous activity, toward what we call a good society. It is not American, or even Western, in its model. It is variable, and in its application to particular cultural contexts may yield different results, as different as the peoples, cultures, and stories of the regions that undertake the work of living together amidst our differences. And yet it is coherent in its desire to move beyond diversity and tolerance, toward a proactive and balanced partnership between constitutionality and culture, rules and relationship, powered by a constructive pragmatism. We could do much worse than adopt the best of the models this essay has surveyed, and that is just what covenantal pluralism aims to do.

Acknowledgements

This article was commissioned as part of a larger project sponsored by the Covenantal Pluralism Initiative at the Templeton Religion Trust. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of the Templeton Religion Trust.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert J. Joustra

Robert J. Joustra is Associate Professor of Politics & International Studies at Redeemer University. He is author and editor of several books, including The Religious Problem with Religious Freedom (Routledge, 2017) and most recently Modern Papal Diplomacy and Social Teaching in World Affairs (Routledge, 2019). He serves as an editorial fellow at The Review of Faith & International Affairs.

Notes

1 The idea and the plotting of these pluralisms was developed with Jessica R. Joustra. I thank her for her creative insights!

2 For an assessment of the utility of such pluralism for such things as prosperity and stability see the work of Brian Grim at the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation, here: https://religiousfreedomandbusiness.org/brian-j-grim.

3 There are important accounts of pluralism which deal mainly with structural or cultural pluralism, and some, like principled pluralism or confident pluralism, are connected in important ways to their organized response to directional pluralism, but that is not the subject of this essay.

4 In International Relations, one tradition that deals with wide-scale pluralism along such pragmatic lines is called functionalism. The premise is similar, in that productive relationships can be built across wide difference on the basis of pragmatic—or functional—need.

References

- Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bhargava, Rajeev. 2011. “Rehabilitating Secularism.” In Rethinking Secularism, edited by Craig Calhoun, Mark Juergensmeyer, and Jonathan Van Antwerpen, 92–113. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bhargava, Rajeev. 2012. “How Should States Deal with Deep Religious Diversity?” In Rethinking Religion and World Affairs, edited by Timothy Samuel Shah, Alfred Stepan, and Monica Duffy Toft, 73–84. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brink, Paul. 2012. “Politics Without Scripts.” Comment Magazine, November 1. https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/politics-without-scripts/.

- Carlson-Thies, Stanley. 2018. “The Dissatisfactions – and Blessings! – of Civic Pluralism.” Public Justice Review 8 (4). https://cpjustice.org/index.php/public/page/content/pjr_vol8issue4_no1_carlsonthies_dissatisfactions_b.

- Chan, Joseph. 2014. Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chaplin, Jonathan. 2006. “Rejecting Neutrality, Respecting Diversity: From ‘Liberal Pluralism’ to ‘Christian Pluralism’.” Christian Scholars Review 35 (2): 143–175.

- Chaplin, Jonathan. 2016. “Liberté, Laicité, Pluralité: Towards a Theology of Principled Pluralism.” International Journal of Public Theology 10: 354–380.

- Connolly, William E. 1999. Why I am Not a Secularist. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Connolly, William E. 2005. Pluralism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Deede Johnson, Kristen. 2007. Theology, Political Theory, and Pluralism: Beyond Tolerance and Difference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eck, Diana. 2015. “Pluralism: Problems and Promise.” Journal of Interreligious Studies 17: 54–62.

- Eck, Diana. 2020. “From Diversity to Pluralism.” The Pluralism Project. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://pluralism.org/from-diversity-to-pluralism.

- Farr, Thomas. 2008. World of Faith and Freedom: Why International Religious Liberty is Vital to American National Security. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Geiss, Mary Ellen. 2020. “These Colleges Want to Make Their Campuses Laboratories for Bridging Divides.” The Aspen Institute, February 7. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/blog-posts/these-colleges-want-to-make-their-campuses-laboratories-for-bridging-divides/.

- Goodman, Lenn. 2014. Religious Pluralism and Values in the Public Sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guinness, Os Guinness. 2013. The Global Public Square: Religious Freedom and the Making of a World Safe for Diversity. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

- Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman. 2015. Beyond Religious Freedom: The New Global Politics of Religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Inazu, John. 2016. Confident Pluralism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Inazu, John. 2018. “Hope Without a Common Good.” In Out of Many Faiths: Religious Diversity and the American Promise, edited by Eboo Patel, 133–150. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Joustra, Robert J. 2018. The Religious Problem with Religious Freedom: Why Foreign Policy Needs Political Theology. New York: Routledge.

- Joustra, Robert J. and Jessica R. Joustra. Forthcoming. “Are Calvinists for Pluralism? The Politics and Practice of a Protestant Possibility.” In The Routledge Handbook of Religious Literacy, Pluralism, and Engagement, edited by Chris Seiple and Dennis R. Hoover. Oxford: Routledge.

- Kaemingk, Matthew. 2018. Christian Hospitality and Muslim Immigration in an Age of Fear. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Keller, Timothy, and John Inazu. 2020. Uncommon Ground: Living Faithfully in a World of Difference. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson.

- Koyzis, David T. 2019. Political Visions & Illusions: A Survey and Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press.

- Levin, Yuval. 2020. A Time to Build: From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus. How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream. New York: Basic Books.

- Maclure, Jocelyn, and Charles Taylor. 2011. Secularism and Freedom of Conscience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2016. Religious Difference in a Secular Age: A Minority Report. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Marsden, George. 2015. “A More Inclusive Pluralism: A Constructive Proposal for Religion in a Pluralistic Society.” First Things, February. https://www.firstthings.com/article/2015/02/a-more-inclusive-pluralism.

- Mouw, Richard, and Sander Griffioen. 1993. Pluralism and Horizons. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Neo, Jaclyn. 2017. “Secularism Without Liberalism: Religious Freedom and Secularism in a Non-Liberal State Symposium: Is Secularism a Non-Negotiable Aspect of Liberal Constitutionalism.” Michigan State Law Review, 2017 (2): 333–370.

- Neo, Jaclyn. 2020. “Regulating Pluralism: Laws on Religious Harmony and Possibilities for Robust Pluralism in Singapore.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 18 (3): 1–15.

- Noll, Mark, David Bebbington, and George Marsden. 2019. Evangelicals: Who They Have Been, Are Now, and Could Be. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Patel, Eboo. 2016. Interfaith Leadership: A Primer. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Patel, Eboo. 2018. Out of Many Faiths: Religious Diversity and the American Promise. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Patel, Eboo. 2020. “The Campus and the Culture Wars.” Inside Higher Ed, February 14. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/conversations-diversity/campus-and-culture-wars.

- Patel, Eboo and Cassie Meyer. 2010. “Building Religious Pluralism: The Interfaith Youth Core Approach.” International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction VII (1): 167–172.

- Patton, Laurie L. 2006. “Toward a Pragmatic Pluralism.” Emory Magazine, Autumn. https://www.emory.edu/EMORY_MAGAZINE/autumn2006/essay_pluralism.htm.

- Rawls, John. 1993. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Seiple, Chris. 2018a. “Faith Can Overcome Religious Nationalism: Here’s How.” World Economic Forum, April 18. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/faith-can-overcome-religious-nationalism-heres-how/.

- Seiple, Chris. 2018b. “The Call of Covenantal Pluralism.” Templeton Lecture on Religion and World Affairs. Foreign Policy Research Institute, November 13. https://www.fpri.org/article/2018/11/the-call-of-covenantal-pluralism-defeating-religious-nationalism-with-faithful-patriotism/.

- Seligman, Adam, Rachel Wasserfall, and David W. Montgomery. 2016. Living with Difference: How to Build Community in a Divided World. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Skillen, James W. 1994. Recharging the American Experiment: Principled Pluralism for Genuine Civic Community. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.

- Stewart, W. Christopher. 2018. “Ministerial Philanthropy Panel Remarks at US State Department,” July 24, https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/2018/10/Ministerial-Panel-Remarks-23JULY2018-Chris-Stewart-1.pdf?_ga=2.146392060.956419236.1585346935-1222409484.1584028242.

- Stewart, W. Christopher, Chris Seiple, and Dennis R. Hoover. 2020. “Toward a Global Covenant of Peaceable Neighborhood: Introducing the Philosophy of Covenantal Pluralism.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 18 (4): 1–17.

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, Harvard University Press.

- Taylor, Charles. 2010. “Solidarity in a Pluralist Age.” IWMpost, April–August. Newsletter of the Institut fu˝r die Wissenschaften vom Mencschen. No. 104.

- Taylor, Charles. 2011. “Why We Need a Radical Redefinition of the Secular.” In The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere, edited by Eduardo Mendieta and Jonathan Van Antwerpen, 34–59. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Williams, Rowan. 2012. Faith in the Public Square. London: Bloomsbury.