ABSTRACT

This paper explores the tensions that arise when museums adopt a particular moral and political standpoint while at the same time attempting to recognize and making space for a plurality of perspectives. The study draws on a visual, textual, and comparative analysis of two exhibitions: Typical at the Intercultural Museum and FOLK: from racial types to DNA sequences at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology, both located in Oslo, Norway. Alongside interviews with the exhibition producers, the analysis examines how the exhibitions communicate certain standpoints in relation to questions of diversity and demographic changes in contemporary Norway, while simultaneously facilitating an open dialog and debate. The findings suggest that these two roles can be hard to reconcile and ultimately influence museums’ attempts at creating genuine spaces for democratic debate.

Introduction

In an age of accelerated globalization, where migrations are increasing, and national populations are becoming more diverse, questions of the social and societal role of the museum are accentuated. Contemporary institutions are under growing pressure to stay relevant to fast-changing societies. In Norway, as in other European nation-states, the increased inflow of immigrants and refugees during the last few years has triggered a surge of right-wing populism. Divisive discourses are on the rise on the political scene and within mass and social media. Responding to such developments, museums are adopting explicit agendas and practices of inclusion and multivocality. In Norway, this is not a particularly new movement; over the last decades governmental policies, funding programs and guidelines for the culture sector have pushed a liberal model of multiculturalism. The rhetoric is cast in terms of a “celebration of diversity,” and museums are presented as arenas for fostering inclusive identities, combating prejudice, promoting tolerance, and facilitating understanding. As public institutions, they should move away from hegemony and reflect a diversity of perspectives and realities.

The increased focus on the power of museums to take an active societal role has led several scholars to promote an activist museum practice, which highlights how museums have the ability to take explicit political and moral positions on issues that hold the capacity to generate fiercely opposing views (e.g. Janes & Sandell, Citation2019; Sandell et al., Citation2010). Internationally, recent events have emphasized the societal role of museums further, such as the #MuseumsAreNotNeutral online campaign challenging the supposedly “neutral” status of museums, and the response made by several museums in support of the Black Lives Matter protests during 2020. Museums have also been among the targets of calls to decolonize academia, where institutions have been encouraged to rename and remove iconography that celebrates figures of colonial power (Haynes, Citation2019).

However, in a globalized society where conflicting outlooks and beliefs cannot be willed away, how can museums adopt a particular standpoint, and thereby direct people towards a particular world view, while at the same time recognizing and making space for a plurality of perspectives? In many ways, institutions are faced with a balancing act between two roles that can be difficult to reconcile, and which may lead to rather different practices and outcomes. This paper explores tensions that arise between these roles through the visual, textual, and comparative analysis of two exhibitions; Typical at the Intercultural Museum and FOLK: from racial types to DNA sequences at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology, both located in Oslo, Norway. The study examines how the curatorial projects respond in various ways to questions and challenges of diversity and demographic changes by communicating specific messages and inviting visitors to participate in the creation of meaning and knowledge. The findings are brought into a wider discussion on museums as spaces for democratic debate and the possibilities and limitations that lie within such approaches.

The societal role of museums

Museums have, throughout each period of their existence, embodied and shaped their visitors' perceptions of what is valuable, important and true (Bennett, Citation1995; Ferguson, Citation2010, p. 36). This, together with the early museums' alleged ability to present objective, immutable facts, and truths about the world, enabled museums to develop as instruments of power, as sites of power-knowledge (Ferguson, Citation2010, p. 36). This power has, however, been thoroughly criticized over the last 30 years, and with the introduction of the “new” and “critical” museology, the field has seen an increased awareness and development of a new museum paradigm that is geared toward social inclusiveness and has the capacity to positively influence contemporary audiences (Hauptman & Svanberg, Citation2013, p. 148; Williams, Citation2010, p. 21). In Norway, political documents have been explicit in that the museums should change from hegemonic institutions with the power to canonize certain cultural values and forms of expression at the expense of others, to democratic and inclusive institutions which champion diversity and complexity (Holmesland, Citation2013; Kultur-og kirkedepartementet, Citation2009; Kulturdepartementet, Citation1996, Citation1999). As a result, the societal role of museums has become a central theme in subsidy programs and museum projects, and many cultural institutions proclaim their societal role on their websites and in their statutes (ABM-utvikling, Citation2006; Arts Council Norway, Citation2015, Citation2018; Hylland, Citation2017). At the same time, concerns regarding this role are being voiced among museum professionals. Questions relate to the challenges posed by engaging with issues that divide opinion and whether it is possible to take an active stance while at the same time creating a genuine space for dialog and debate (Vlachou, Citation2019, pp. 47, 54). The study will explore this apparent paradox and emphasize the tensions that may arise between these perceived conflicting roles.

The museum as text

The following analysis focuses on how the two exhibitions, through the use of objects, design, and texts, balance between taking specific standpoints relating to diversity and demographic changes while at the same time encouraging debates and visitor meaning-making. Louise Ravelli’s (Citation2006) tools for analyzing how museums communicate through text has been applied on both exhibitions, with a focus on genre, roles, and appraisal. Genre has been used to decide the text types in the exhibition, which again can be used to tell the overall purpose of that text – to instruct, to tell a story, to convey knowledge, or to influence visitors in a certain way (Citation2006, p. 19). Roles examines the way the museums interact and communicate with their visitors – for example as authoritative, equal or distant (Citation2006, p. 73) – while appraisal is a resource for incorporating opinion in a text, and is often used to encode a point of view (Citation2006, p. 92). Ravelli’s approach sees the exhibitions as multi-modal texts where meaning is generated through a variety of semiotic resources, such as language, design, color, and lighting. This involves the analysis of actual texts in the exhibitions – introductory texts, labels, etc. – but also by looking at the “museum as text,” how different combinations of elements in the exhibitions can “prioritize some meanings […] over others” and “facilitate particular forms of visitor interaction” (Ravelli, Citation2006, p. 121). In addition, Stephanie Moser’s (Citation2010) framework for display analysis has been useful in terms of looking at different details of display in order to examine how they act as active agents in the production of knowledge. Interviews with the exhibition producers at both museums are presented alongside the exhibition analysis. The interviews were important in order to understand the aims and challenges behind curatorial choices and to shed light on possible discrepancies between perceived and intended messages in the exhibitions. The inclusion of visitor perspectives was unfortunately outside the scope of the research done in preparation for this paper (see Sontum, Citation2019 for a recent visitor study of the FOLK exhibition).

Exhibiting prejudice

The permanent exhibition Typical opened in June 2017 at the Intercultural Museum in Oslo. The exhibition explores the concept of prejudice and presents questions such as; what is prejudice, and where does it come from? What consequences can result from prejudice, and how can we stop them? Through the use of humor, conceptual art, and interactivity, visitors are encouraged to share and reflect upon their own prejudices.

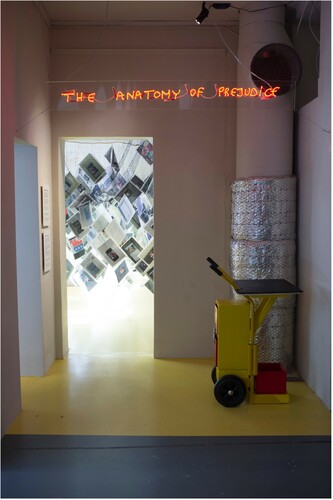

The Intercultural Museum is a museum without a physical collection of artifacts – it collects stories. This absence of artifacts is also noticeable in Typical. The exhibition is comprised almost exclusively of texts and interactive activities. An introductory panel presents the theme and calls attention to current challenges of diversity in multicultural Norway, such as an increasingly divisive rhetoric in public and political debate, mass media, and online platforms. In the main exhibition space several text panels explain the origin of the word “prejudice” and how this emerges through categorization and socialization. The museum also presents its own definition of the term, namely the “categorization of people which is unjustified and negative.” Two activities directly relate to these texts and encourage visitors to categorize and “pigeonhole” themselves. Four small rooms explore the term further by connecting prejudice to different feelings. The rooms labeled “HUMILIATION,” “PRIDE,” “HATE,” and “FEAR” contain texts, as well as audio and video installations, discussing themes such as discrimination and social exclusion, hateful speech, and xenophobia. Several works by the artist Thierry Geoffroy are present in the exhibition. In three video installations, the artist tries, through the use of humor, to make people admit to being prejudiced, and a room with the neon sign “The Anatomy of Prejudice” contain the art installation the “Jungle of Prejudice.” Here visitors are encouraged to participate in the creation of the artwork by printing an example of a personal prejudice and “share it as a leaf in the Jungle of Prejudice” – that is, hang them on wires suspended from the roof. This has resulted in a room filled with sheets of paper where other visitors are able to move through and read the contributions. These represent a variety of themes, such as prejudice against bloggers, against dark-skinned people, against people with a different world view, against supporters of Donald Trump, and statements such as “Norwegians are not social” and “all elderly Norwegian ladies are racist.” The interactive elements are important parts of the exhibition. The aim behind them are, according to Contents Editor Anders Bettum, that:

[…] we want people to come in and analyze their own stuff, experiences, thoughts, ideas, their own awareness around prejudice. So, they have to do that themselves, we cannot do it for them. We also wanted the visitors themselves to show other visitors what they think.Footnote1

The “Jungle of Prejudice” is one of very few elements in the exhibition that directly alludes to population groups especially vulnerable to prejudice and discrimination. The absence of such groups and their stories elsewhere in the exhibition was, however, a conscious choice by the exhibition producers. Exhibition Architect Annelise Bothner-By expressed it as one of the pitfalls during the making of the exhibition: “When you choose examples, to what degree do you amplify prejudice? When we think we should dissolve [prejudice], and instead we end up highlighting prejudice and they become stronger than they were” ( and ).

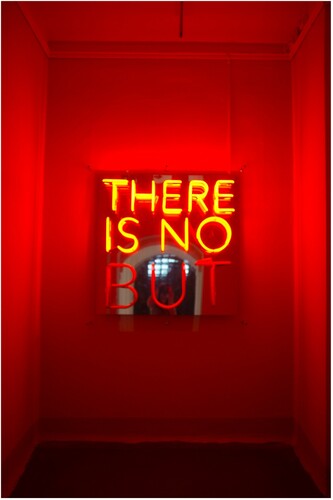

Typical is quite explicit in its communication, and the use of textual elements to convey certain moral standpoints appear throughout the exhibition. The texts as a whole express an attempt at conveying the message that prejudice is negative. This is done in very explicit ways, as in one of the introductory texts: “In this exhibition, we consider prejudice as a social problem,” or subtler, as in a text discussing prejudice and its connection to genocide: “there is no reason to keep silent, if you experience that the society is moving in a dangerous direction.” Some texts actively encourage self-reflection: “How dangerous are our prejudices, and is it possible to change them?” Project Director Gazi Özcan explained: “What we want is for people to become aware of their prejudices, and that [these prejudices] can have fatal consequences, if you don't pay attention” ().

Figure 3. The art installation “There is no but” by Thierry Geoffroy. Photo: Martine Scheen Jahnsen.

The exhibition takes a clear moral position throughout by commenting on the current political and social climate in Norway. One example is the room titled “FEAR.” Here, a critical finger is directed at the news industry, accusing them of enhancing feelings of fear and xenophobia toward the increase in Middle Eastern immigrants into Norway. The room contains large posters of front pages and articles from a variety of Norwegian newspapers. They are all coverage of the increasing number of immigrants arriving in Norway and include headlines such as “Islamic extremists are hunting Norwegians”, “Fear that they will bring terrorism home to Europe” and “Oslo has become so unsafe that you don't know if you will return home alive”.Footnote2 The museum shows its attitude towards headlines such as these quite clearly through a couple of text panels. One of them, a text discussing how “fear begets danger,” includes clear references to the front pages and articles on display as it is argued that by “contributing to a sentiment of fear without good reason,” politicians and the media contribute to “creating new social problems.” The museum text encourages visitors to let themselves be exposed to whatever they fear, and as such, reduce the xenophobia that the news industry contributes to. Several of the front pages include photos of the “stereotype terrorist”; men with their faces covered by a scarf and holding a large gun. By enlarging these pages a great deal, calling attention to the rhetoric and semiotics used, the museum adopts a clear position on the fearmongering used by the news industry. Taking a stance on issues such as these was also a conscious choice. Bothner-By explained that it was important “to make it clear that we think prejudice is wrong. We don't need to be neutral here, we can be a bit moralizing. This is for the best because we know what we say, clearly stating what we mean.”

The texts as a whole also exemplify the way the museum intends to interact with their visitors, the different roles which the institution and the visitors can and do take up ( and ). By presenting clear statements and taking up a particular moral position, the museum takes a fundamentally authoritative role and is in charge of the communication. The visitors are encouraged to acknowledge and agree with the statements but not respond. However, by also including questions and encouragements, the role sometimes shifts. This way, the exhibition balances between taking a clear moral and political standpoint on the one side while at the same time releasing some of the tension by inviting visitors to contribute with their own stories and perspectives. These roles were also commented on by Bettum:

This couldn't be an exhibition where we were to force our knowledge on people. To find precise definitions of prejudice is hard, you do have racism and the like, but they are also common concepts which everyone has a relationship with and has strong opinions about. So, finding a balance and inviting people to bring their own reflections, their own experiences, and share them, that is the core of [the exhibition].

Figure 4. Detail from the room “FEAR.” The front page reads “Islamic extremists are hunting Norwegians”. Photo: Martine Scheen Jahnsen.

Figure 5. Four small rooms explore prejudice in connection to different feelings. Photo: Martine Scheen Jahnsen.

As exemplified here, Typical takes a strong moral position when commenting on current challenges in a multicultural Norway. At the same time, by including a number of activities, interactive elements, and questions, an effort is made to include other perspectives and viewpoints, and by that counterbalance the museum’s voice. However, the moral tone adopted throughout might be seen to limit the attempt of creating a true space for dialog and debates. Before this is discussed further, a different approach taken in the exhibition FOLK at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology will be analyzed.

Exhibiting race

FOLK – from racial types to DNA sequences was a temporary exhibition from March 2018 until December 2019 at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology in Oslo. It was produced by the National Medical Museum, an integrated part of the Museum of Science and Technology. The exhibition explored how racial sciences from the Enlightenment until the present have identified and valuated biological similarities and differences between humans and how this research has been shaped alongside changing social ideas on race, identity, and belonging.

The exhibition space was dominated by two large, round structures. The first structure, titled “A new curiosity cabinet” consisted of a rounded wall with display cases set into it. The objects in the display cases consisted of both old and new artifacts, all functioning as examples of how people have been stereotyped, romanticized and valued in the past and the present. The objects included a hair color chart, wax ethnographic busts, an anti-Semitic caricature, a post card with a drawing of the “Nordic race,” a contemporary DNA self-testing kit, and so on. Almost the entire right-hand wall of the exhibition was devoted to photographs originating from a large survey funded by the Norwegian government in 1920–1921 in order to examine the nation’s racial composition, and thus be able to locate different “races”, such as the “Alpine,” “Lappish,” and “Nordic” race. There were black-and-white photographs from a large-scale survey of young military recruits, as well as photos from field trips which aimed at studying the “Lappish” and “Nordic” races, with the underlying perception of the Sami as racially more primitive. The far back wall of the exhibition included examples of racial science done between the 1920s and 1950s. Through the use of objects, posters and texts, the concepts of racial hygiene, racial science and nation-building, and the alleged superiority of the “Nordic” race were explored. This section also included several examples of anti-racism movements from the post-war period, such as photos from anti-apartheid demonstrations in South Africa and the civil rights movement in the USA. The left-hand wall of the room was devoted entirely to four large wall-mounted flat screens. The videos shown consisted of interviews with scientists working with genetics and DNA research today, as well as animated films explaining genetic research and human variation. The second large, round structure combined all of the other themes in what was titled “The archive.” Four sections of rounded open shelves displayed objects used within sciences studying human variation, dating from the beginning of the twentieth century up until today ( and ).

Figure 7. Photos from fieldtrips done during the 1920s in order to study the “Nordic” and “Lappish” races. Photo: Håkon Bergseth/Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology.

In the same manner as Typical, FOLK also included texts which put forward arguments in an attempt to influence visitors to agree. The introductory text, for example, was a quite authoritative text showing the relevance of the exhibition today. It pointed out that even though “the heyday of scientific racism is over” many of these outdated ideas continue to affect us, and “racism still exists in our societies.” It ended with an almost warning-like sentence; that the exhibition would point to “the profound consequences that such research can have for society and the lives of individuals.” This text reflected the aims of the exhibition as presented by the museum staff. As expressed by one of the Lead Curators, Ageliki Lefkaditou:

I think the main goal for me would be to bring to the public discussion an issue that has been tabooed, it has not been discussed publicly: how have we in this society, but also internationally, been dealing with human diversity […] and whether this has changed so radically or not […].

The second Lead Curator, Jon Kyllingstad, explained how they wished to convey a certain message by “problematizing both historical research and the modern contemporary research in this field. Not just negatively criticize, but problematize, contribute so that people can reflect upon how research is undertaken and is practiced in society.” This was evident in several texts which used suggestions and invitations to involve visitors in an active exploration of the exhibition. The introduction text to “the curiosity cabinet” for example, stated that: “a new encounter with these unusual and surprising objects challenges us to rethink the ways in which people and cultures have been stereotyped, romanticized, and valued – in the past, present, and future” (emphasis added). Also, the introduction text to “the archive” stated that: “we invite you to use the objects collected here to contemplate and discuss these objects” (emphasis added). Even though textual elements such as these opened up for a co-creation of meaning, they also pointed to an agenda behind the exhibition; visitors should be critical when examining the objects on display, and hopefully agree that the ideas connected to them are dangerous. As explained by Kyllingstad: “we do wish to influence people in a certain direction. […] influence people to think sensibly about the questions that we address.” As such, a balance was attempted between the museum’s position and the act of inviting visitors to contribute. However, this might still be seen to favor the museum’s voice as the encouragements directed the visitors toward a certain moral framework ( and ).

Figure 8. Detail from “The archive.” Photo: Håkon Bergseth/Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology.

Figure 9. Nazi and eugenics propaganda posters and anti-racism movements in FOLK. Photo: Håkon Bergseth/Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology.

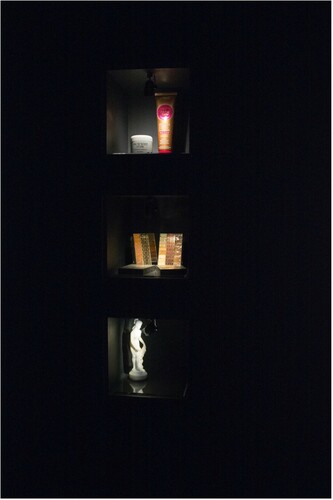

A specific world view was also disseminated by the juxtaposing of objects and themes in order to create certain effects. One example is “the curiosity cabinet” where old and new artifacts were displayed together which allowed for a certain creation of meaning (Moser, Citation2010, p. 27). The combination of older and contemporary artifacts and their placement in separate display cases allowed visitors to view the displays as separate stories, while at the same time creating effective links between past and present ideas and research methods. The placing of some display cases in closer proximity to each other also created different narratives, which was possible for visitors to “read” as they moved through the exhibition. For example, the vertical ordering of three displays containing contemporary self-tan and whitening creams, a chromatic scale used during the twentieth century in order to racially classify people, and a miniature classical statue, can be seen as a comment on how skin color is related to classification and different ideas of beauty. The objects, when seen together, communicated a critical message, drawing parallels between the different ideas of race and skin color that are connected to them ().

Even though it was possible to draw out specific messages in the exhibition, this was done in a subtle way. This low-key subjectivity was expressed as an important premise during the exhibition-making process by Kyllingstad: “We discussed [how explicit we should be] a lot. In the project group, there were many voices that wanted to avoid being too didactic, […] that people should think for themselves, be more open for reflection rather than one-way learning.” This subtleness was also evident in the few interactive elements present in the exhibition. One example is a number of drawers in “the archive” which the public could open and close as they pleased. The act of letting the visitors interact with the exhibition, even if it was just opening and closing drawers, made the museum seem less authoritative, encouraging visitors to “discover” knowledge on their own. However, even though the exhibition to a large degree avoided a didactic tone, the opinion of the curators did sometimes shine through. One of the drawers in the archive, for example, contained a couple of highly controversial books – The Bell Curve, and A Troublesome Inheritance. The texts accompanying them were titled “Twentieth-century racism” and “Twenty-first-century racism” and criticized the books of endorsing prejudice and reproducing insulting stereotypes. Also, the continuous juxtaposing of past and present research and ideas, such as eugenics before and during the Second World War and modern genome and DNA research, disseminated a clear message, even though in a subtle way: there are no human races, but the concept of race has had, and has today, great social and political implications. Lefkaditou explained:

I want people to know that the curators who made this exhibition have this point of view, […] I know there are no races. […] If this issue is controversial, it is not because of what we know from science, but because of how science has been used and is being used, and because of the power relations in society that makes racism not go away.

Kyllingstad stated a similar view: “there is a debate regarding this concept of race, that some defend and some use without thinking. We do have a clear stance that this is a way of thought which is neither scientifically meaningful or socially good.” As such, even though it was done in a subtle way, the FOLK exhibition did take an active position on questions relating to human diversity and attempted at conveying a message with a clear agenda. Visitors were at the same time invited to reflect and discuss, thus encouraging meaning-making and dialog.

The activist museum of many voices

The analyses demonstrate how the two exhibitions balance between taking clear moral positions while at the same time encouraging debate and opening up for co-creation of meaning. The exhibitions come across as quite different in their communication; however, a similarity between them can be seen in the way they position themselves in relation to their visitors. Even though Typical has more interactive elements, they both use textual and design elements that enhance an equal relationship between the institutions and the visitors. The use of suggestions and invitations encourage interaction and co-production of knowledge. Also, the use of pronouns, such as “us,” “we,” and “you” is prominent in both exhibitions, reducing the power difference between the museums and the visitors. This emphasis on visitor participation is central to what Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (Citation2000) has termed the post-museum, a museum which, as opposed to the “modernist museum,” includes many voices and many perspectives and plays a role in partnership with the visitors. As such, by actively involving the visitors, Typical and FOLK can be seen to shift some of the responsibility from the museums, as visitors no longer are regarded as passive recipients of knowledge. Visitors are encouraged to participate in the knowledge production, while at the same time reflect upon their own role in contemporary social issues. This focus on visitor participation can be seen as an attempt at making the exhibitions into spaces where visitors dare to ask questions. For the FOLK exhibition, Lefkaditou stated that:

We want people to feel empowered to ask questions which they might think are tabooed. And that they can put things on the table, like “should we use the terms race and ethnicity in medical research? What does it mean if we do so?” Or questions like “but I do see that there is all this diversity around me, why does it match or not match with the proposition that there are no human races?” Questions that maybe people are afraid to ask, because if they ask them they will be seen as racist or seen as holding on to stereotypes.

Thus, both exhibitions can be seen as attempts at providing visitors with critical thinking skills and by that “better equip people to deal with claims and counter claims they see in the media, and to ask questions and share those question with other audiences” (Cameron, Citation2003, p. 41). FOLK does this by showing the genealogy of contemporary notions of ethnicity and heritage, and how this is presented in social debates, thus making it possible for visitors to come to more critical and complex understandings of these issues, rather than drawing simplistic (and maybe wrong) conclusions to complicated questions. Typical encourages critical reflection by highlighting a concrete problem resulting from the tensions implicit in a more multicultural society. Instead of making solely partisan statements about the benefits of a more diverse society, they point to the real social issue of prejudice and explain its origins and possible outcomes.

Both exhibitions invite visitors to participate in the co-production of meaning. Yet, they also express clear moral standpoints and, while presented in different ways, both communicate specific world views. Few openings are offered for alternative positions and understandings. This is especially prominent in Typical, where the moralizing aspects can appear to actively discourage a different viewpoint. It has been argued that while the promotion of liberal ideas of diversity, equality, and human rights should be explicitly expressed in museums, it is still important to acknowledge the existence of other political and moral orders and that instead of silencing or ignoring them, these antagonisms should be recognized in order to create an adequate response to them (Mouffe, Citation2016; Whitehead et al., Citation2015). This does not mean that those who believe in right-wing extremist ideas should be “given platform” in museums, but that through historicizing them contextually they can be made into “objects of distanced scrutiny” (Whitehead et al., Citation2015, p. 46). Nicole Deufel (Citation2017), drawing on the work of Chantal Mouffe (Citation2013), suggests an agonistic interpretation practice where multiple perspectives, interpretations, opinions, and values are voiced and made visible and where the conflict between different cultures and value systems plays out in a mutually respectful negotiation (Deufel, Citation2017, p. 100). The concept of agonism sets as its premise a conflict of perspectives that cannot be resolved, but that unlike antagonism, the relationship to others is characterized by a recognition of each other’s right to defend one’s ideas (Deufel, Citation2017, p. 100). She argues that museums can create agonistic public spaces that “seeks actively to make visible the views that the dominant view hides and suppresses” (Citation2017, p. 101). Bettum and Özcan from the Intercultural Museum do in fact stress, in a book chapter on inclusive museum practices, that the inclusion of a polyphony of different statements and attitudes in exhibitions, also those that the museum might not share or represent, creates opportunities for the museum to facilitate a democratic debate (Citation2018, pp. 216–217).

Even though both exhibitions do acknowledge antagonisms in today’s society, the more didactic approach taken, especially in Typical, could potentially result in visitors rejecting the message conveyed by the museums and their attempt at influencing. As shown by Wendy Brown (Citation2006) in her analysis of the Museum of Tolerance in L.A., moralistic approaches taken by museums might actually shut down conversation, rather than open up meaningful dialog. Other research has also suggested that explicit attempts at conveying messages about diversity in museums might instead lead to visitors actively resisting these messages and strengthen negative attitudes (Lloyd, Citation2014, p. 154). As such, the explicit stance taken in Typical might limit the very self-reflection that the museum is trying to enhance. Regarding the FOLK exhibition, a recent study (Sontum, Citation2019) demonstrates how young visitors to the exhibition were neither entirely accepting of, nor resistant to, ideas presented in the exhibition. The intended messages of “danger” were acknowledged, but also negotiated based on the youths' lived experiences. However, even though there was little evidence that the youths had any real changes in perspectives, the study demonstrates how “the exhibition encounter functions as a catalyst for critical engagement” (Sontum, Citation2019, p. 53). By historicizing antagonisms, such as the idea of the “Nordic race” – an idea which has experienced an upsurge among current far-right groups in Norway – in a subtler way, the FOLK exhibition might be more successful in creating a space for reflection and dialog.

Even though museums' ability to act as spaces for democratic debate has been advocated by many, there also exists considerable dissensus concerning the extent to which museums should get involved in current social issues, and whether the inclusion of multiple perspectives should be among the museums' many tasks and functions. A recent example is the controversy regarding ICOMs proposed new museum definition. The definition, which was postponed after a General Assembly in September 2019, describes museums as “democratizing, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the past and the futures” with a goal of contributing to “human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing” (ICOM, Citation2019). As such, it has moved a great deal away from the current definition, which states that a museum is a “non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society” with traditional functions such as acquiring, conserving, researching, communicating, and exhibiting. While some welcome the new definition, arguing that museums must be conscious of the strong role they play in society, others criticize it for being a political and ideological manifesto that does not address the traditional functions of a museum (Haynes, Citation2019). Some actors resist the idea of the museum as “polyphonic spaces,” arguing that it does not represent the great variety of museums (Noce, Citation2019), and that it eradicates the professional autonomy of the museum (Snekkestad, Citation2019). The dissensus has been termed a debate between the old guard and the younger generation (Noce, Citation2019), and touches on the questions of who should be able to speak in the museum, what it means for museums to be “political,” and whether true polyvocality is possible or even desirable. Drawing on this further, it can be argued that there are limits to the idea of museums as “polyphonic spaces,” as the ideas which are actually possible to voice within most museums exist within a certain political and social consensus. For example, the societal role adopted by many museums is usually presented as something that brings about “positive change.” However, the idea of what is meant as “positive change” is not an objective, universal notion. What is presented as “positive change” in many Western European museums leaning toward a more activist approach is the idea of liberal progressive politics where multiculturalism is championed, and where difference is accepted or even promoted (Whitehead et al., Citation2015, p. 46). However, as exemplified in the “FEAR” room in Typical, not everyone shares the view that this change is positive. The discussion surrounding museums' ability to function as “polyphonic spaces” rarely considers the limitation that lies within such aspirations. While it has been argued that museums cannot simply “preach to the converted,” but must also engage people with different views (Vlachou, Citation2019), the analysis of Typical and FOLK demonstrates that the stronger a stand taken on a contested topic, the less it opens up for alternative viewpoints.

It is not the intention here to argue that taking a stand is incompatible with creating a genuine space for dialogue and debate. As the analyses demonstrate, the exhibitions attempt to become such spaces, and both encourage critical thinking from their visitors. However, the study also exemplifies the difficulty of adopting an explicit moral standpoint without shutting down alternative views. It can be argued that museums can take explicit political and moral positions while at the same time encouraging multivocality, as long as these remain within a certain liberal democratic discourse.

Conclusion

The introductory questions of this article concerned tensions between an activist museum practice, which involves taking particular moral and political standpoints, and efforts to include a plurality of voices in a society where issues of diversity generate fiercely opposing views. By analyzing the objectives and contents of two exhibitions, the aim was to examine this apparent paradox by highlighting specific examples. Typical and FOLK can be seen as important exhibitions that respond effectively to current questions and challenges of diversity and demographic changes in contemporary Norway. While Typical presents more conclusive “answers,” they both balance between taking an active stance and inviting visitors to contribute with their own perspectives, ask questions and discuss difficult and sensitive issues. However, even though this releases some of the tension, a certain moral position is still encouraged in both exhibitions, and neither can be said to really open up for alternative views. As argued by many, taking standpoints on current social issues should be among the many tasks of a twenty-first-century museum. At the same time, museums are encouraged to function as “polyphonic spaces” that facilitate critical dialogue. However, as exemplified in this study, the perfect balance between these two roles can be argued for and described in theory but seems harder to fulfill in practice.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the exhibition producers at the Intercultural Museum and the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology who kindly agreed to participate in the interviews. I would also like to thank Kaja Hannedatter Sontum for valuable comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sofie Scheen Jahnsen

Sofie Scheen Jahnsen is currently a PhD candidate connected to the research and teaching initiative HEI: Heritage Experience Initiative at the University of Oslo (UiO). She graduated from UiO with an MA degree in archeology in 2015 and an MA degree in museology and cultural heritage studies in 2018. She has previously worked as a research and outreach coordinator for HEI, as well as with several heritage outreach and museum projects, most recently at the University of Oslo and the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. Her doctoral research explores how Scandinavian museums, through the presentation and sharing of food and foodways, are influencing visitors’ perception of heritage and serve as arenas for exploring complex issues of identity and memory in a multicultural society.

Notes

1 All quotes from the interviews are translated from Norwegian by the author, except the quotes from the interview with Ageliki Lefkaditou, which was done in English.

2 All headlines are translated from Norwegian by the author.

References

- ABM-utvikling. (2006). BRUDD. Om det ubehagelige, tabubelagte, marginale, usynlige, kontroversielle.

- Arts Council Norway. (2015). Søknadsskjema for museumsprogrammer 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2018, from https://www.kulturradet.no/documents/10157/02249dca-6152-4ba9-a8ef-5eebfb3b6d07

- Arts Council Norway. (2018). Samfunnsrolle makt og ansvar. Retrieved January 29, 2018, from http://www.kulturradet.no/stotteordning/-/vis/samfunnsrolle-makt-og-ansvar

- Bennett, T. (1995). The birth of the museum: History, theory, politics. Routledge.

- Bettum, A., & Özcan, G. (2018). Dialog som metode – Inkluderingsstrategier ved Interkulturelt museum 2006-2016. In A. Bettum, K. Maliniemi, & T. M. Walle (Eds.), Et inkluderende museum. Kulturelt mangfold i praksis (pp. 181–224). Museumsforlaget.

- Brown, W. (2006). Regulating aversion: Tolerance in the age of identity and empire. Princeton University Press.

- Cameron, F. (2003). Transcending fear – engaging emotions and opinion – A case for museums in the 21st century. Open Museum Journal, 6(1), 1–46.

- Deufel, N. (2017). Agonistic interpretation. A new paradigm in response to current developments. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 26(2), 90–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/ajec.2017.260207

- Ferguson, L. (2010). Strategy and tactic: A post-modern response to the modernist museum. In F. Cameron & L. Kelly (Eds.), Hot topics, public culture, museums (pp. 35–52). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Hauptman, K., & Svanberg, F. (2013). Het historia, svala museer. Nordisk Museologi, 2, 147–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3084

- Haynes, S. (2019, September 9). Why a plan to redefine the meaning of ‘museum’ is stirring up controversy. Time. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://time.com/5670807/museums-definition-debate/

- Holmesland, H. (2013). Museenes samfunnsrolle. Arts Council Norway.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2000). Museums and the interpretation of visual culture. Routledge.

- Hylland, O. M. (2017). Museenes samfunnsrolle – et kritisk perspektiv. Norsk Museumstidsskrift, 3(2), 77–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-2525-2017-02-04

- ICOM. (2019). ICOM announces the alternative museum definition that will be subject to a vote. Retrieved May 3, 2021, from https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-announces-the-alternative-museum-definition-that-will-be-subject-to-a-vote/

- Janes, R. R., & Sandell, R. (2019). Museum activism. Routledge.

- Kultur- og kirkedepartementet. (2009). St.meld. nr. 49 Framtidas museum. Forvaltning, forskning, formidling, fornying. Oslo.

- Kulturdepartementet. (1996). NOU 1996: 7. Museum: Mangfald, minne, møtestad. Oslo.

- Kulturdepartementet. (1999). St.meld. nr. 22. Kjelder til kunnskap og oppleving. Oslo.

- Lloyd, K. (2014). Beyond the rhetoric of an “inclusive national identity”: understanding the potential impact of scottish museums on public attitudes to issues of identity, citizenship and belonging in an age of migrations. Cultural Trends, 23(3), 148–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2014.925279

- Moser, S. (2010). The devil is in the detail: Museum displays and the creation of knowledge. Museum Anthropology, 33(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1379.2010.01072.x

- Mouffe, C. (2013). Agonistics: Thinking the world politically. Verso.

- Mouffe, C. (2016). Democratic politics and conflict: An agonistic approach. Política Común, 9(20210301). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/pc/12322227.12320009.12322011?view=text;rgn=main

- Noce, V. (2019, August 19). What exactly is a museum? Icom comes to blows over new definition. The Art Newspaper. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/what-exactly-is-a-museum-icom-comes-to-blows-over-new-definition

- Ravelli, L. (2006). Museum texts: Communication frameworks. Routledge.

- Sandell, R., Dodd, J., & Garland-Thomson, R. (2010). Re-presenting disability. Activism and agency in the museum. Routledge.

- Snekkestad, P. (2019, August 23). ICOM for ideologer? Museumsnytt. Retrieved May 6, 2021, from https://museumsnytt.no/icom-for-ideologer/?fbclid=IwAR0eQVC_gMbZbFutTNod0YqwbWmC4-R9R6qSoU4_rfkXGc_HPersB6DAX7I

- Sontum, K. H. (2019). The co-production of difference? Exploring urban youths’ negotiations of identity in meeting with difficult heritage of human classification. Museums and Social Issues, 13(2), 43–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15596893.2018.1603031

- Vlachou, M. (2019). Dividing issues and mission-driven activism. Museum responses to migration policies and the refugee crisis. In R. R. Janes & R. Sandell (Eds.), Museum activism (pp. 47–57). Routledge.

- Whitehead, C., Mason, R., Eckersley, S., & Lloyd, K. (2015). Place, identity and migration and European museums. In C. Whitehead, K. Lloyd, S. Eckersley, & R. Mason (Eds.), Museums, migration and identity in Europe: Peoples, places and identities (pp. 7–60). Ashgate.

- Williams, C. (2010). The transformation of the museum into a zone of hot topicality and taboo representation: The endorsment/interrogation response syndrome. In F. Cameron & L. Kelly (Eds.), Hot topics, public culture, museums (pp. 18–34). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.