ABSTRACT

Climate change, species extinction and accelerating inequalities are manifestations of a more fundamental crisis facing humanity: the global dominance of a capitalist/colonialist world order based on logics of extraction and exploitation. The modern, “universal” museum is implicated in this history. It is not only that the accumulation of exotic things was made possible through mercantile and colonial territorial expansion, but the transformation of such things into “objects of knowledge” and their incorporation into universalizing knowledge systems, given architectural expression in the museum, involved forms of epistemic violence that rendered other ways of knowing, understanding and being in the world non-existent. As part of the project of decolonizing the museum, this article questions whether this process of “epistemicide” was indeed so complete, considers whether marginalized forms of knowledge may be reactivated in historical collections, and imagines the role of the “pluriversal museum” in contributing to the shaping of more just and sustainable planetary futures.

The museum in ruins

Two artworks set the scene for my reflections in this article. Created over two centuries apart, they both invoke the museum in ruins. Each, it might be argued, marks the collapse of an era, along with its museological paradigm, and poses a question about what follows. In most other respects, they are very different.

Hubert Robert’s famous painting of 1796, Vue de la Grande Galerie du Louvre en ruine (), depicts this most lavish of the royal galleries of the Palais du Louvre as an antique ruin. The gallery is open to the sky, the debris from its vaulted ceilings lies in fragments on the ground among the broken sculptures; the torso of Michelangelo’s toppled Dying Slave is prominent in the foreground. Plants have taken root in the crumbling masonry; paupers warm themselves beside a brazier. Commoners wander freely in derelict precincts from which they were previously excluded. Robert’s Vue imaginaire depicts the aftermath of the violent collapse of the Ancien Régime and, with it, the privileged, exclusive museology of the princely collection housed in sumptuous palatial grandeur.

Figure 1. Hubert Robert, Vue de la Grande Galerie du Louvre en ruine, 1796. © 2007, RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi.

Amid this ruination, a single statue remains standing: the Apollo Belvedere, which, to eighteenth-century eyes, embodied the purest expression of classical beauty. Enthralled before the statue, an artist sits with a drawing board on his lap, his arm outstretched to Apollo, just as Apollo seems to be reaching out to the artist. This reciprocation between “art” and “artist” (art and its public) at the heart of the painting transcends the surrounding cataclysmic scene, heralding a new political order and a new museological paradigm.Footnote1 Rising, phoenix-like, from the Grande Galerie en ruine is the inauguration of the Louvre as the world’s first universal museum (Duncan & Wallach, Citation1980, p. 457; McClellan, Citation1994).Footnote2

The public opening of the Musée Central des Arts in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre in 1793 preceded the completion of Robert’s painting. There is, however, another curious anachronism in this Vue, one that reminds us that while the royal collection gave way to the public museum, the public museum was no less entangled in the violences of imperial ambition and colonial expansion. It was not until 1800 that the actual, rather than the imaginary, Apollo Belvedere was put on display in the Louvre’s Grande Galerie; it being among over 100 artistic treasures “confiscated” in the name of the new French Republic from the Vatican following Napoleon’s conquest of northern Italy (Gould, Citation1965; Quynn, Citation1945). (It was returned to the Vatican in 1815 following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo.)

If Robert’s painting marks the end of the royal collection and inauguration of the universal museum – public, encyclopedic, modern and, to reference Dan Hicks’ (Citation2020) recent work, brutally imperialistic – the second artwork which introduces my discussion invokes a paradigm shift occurring in our own time. This is Mark Dion’s installation of 2006, The Museum in Ruins (). In contrast to the overt symbolism of Robert’s canvas, Dion’s is an understated work, though no less allegorical.

Figure 2. Marc Dion, The Museum in Ruins, 2006. Photo: Lisa Rastl. © Reproduced with kind permission of the artist and Georg Kargl Fine Arts, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

Like many of Dion’s installations, The Museum in Ruins plays with the medium of the museum itself, and particularly with the universal museum’s primary technology of display: the vitrine. This example brings to mind the disused display cases that one sometimes encounters in neglected corners of the storerooms of provincial museums. In (and on) the vitrine, there is the trace of some kind of order: “nature” on one side, “culture” on the other. Taxidermized birds are grouped on one shelf, shells, and ceramic models of fruit on another. Four moth-eaten stuffed monkeys – evoking, but also mocking, “the ascent of man” – are covered by a plastic dust sheet on top.

On the right side of the display case hangs an orderly array of old scissors: more evidence of the hand of the classificatory mind. Beneath them, heaped up like the broken sculptures and rubble in Robert’s Grande Galerie en ruine, historical, ethnographic, archaeological and art objects are jumbled like flea market curios. Here, it is as if the (disciplinary) structures that separated them and gave them (epistemic) value have collapsed and reduced them to the same undistinguished category: junk.

Dion’s vitrine speaks of the ruins of the modern universal museum – the successor to the princely collection – with its penchant for cutting up and separating the world according to classificatory schema and taxonomies. A disciplined, but murderous dissection of the living planet and its interdependent species and cultures. Exotic animals, botanical specimens, art and artefact (a confusion, in fact, of nature-culture): debris of empire, now redundant, irrelevant, gathering dust, and yet somehow retained, still existent.

Whereas Robert’s Vue imaginaire anticipates a new epoque, and a new museological paradigm, rising from the palace ruins, Dion’s installation does not project a particular vision of the future with similar confidence. Instead, it poses an open-ended question about the relation between past, present and future: What are we to do with this inheritance? What are we to do with these objects of knowledge, and ways of understanding, that were previously invested with such significance? What do we keep? What do we discard?

In the face of anthropogenic mass species extinction, biodiversity loss, climate change, pandemics and escalating global inequalities, the confident narratives of scientific knowledge and civilizational progress embodied in the universal museum, and replicated in miniature in the vitrines of countless provincial museums, strike us now as deeply flawed, delusional and part of the problem. We look on the universal museum in ruins, but what do we envision replacing it?

The epistemological promise of crisis

This article was originally presented at an international symposium entitled “The Future of Museums” organised by the Centre Norbert Elias, Avignon Université and MuCEM (the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations) in association with the journal Culture & musées in November 2021. Having recently emerged from the most serious waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the closure of museums across the world for extended periods in 2020 and 2021, there was a renewed sense of precarity in the cultural sector. The invitation to the symposium referred to “crisis,” “rupture” and “uncertainty,” but the particular crisis or rupture was left unstated.

There is a cartoon by the Canadian artist Graeme MacKay, originally published in the Hamilton Spectator in 2020, showing a succession of tsunami waves approaching shore, each more monstrous in scale compared with the cityscape it is about to obliterate. The waves are labeled “COVID-19,” “Recession,” “Climate Change” and “Biodiversity Collapse”. The response from the city authorities? “Be sure to wash your hands and all will be well”. One can add to or change the names of these waves of crisis that are already engulfing us, and one can substitute any number of grossly inadequate expert responses that offer up platitudes as solutions. It is imperative that we find responses that are proportionate with the problem.

Of course, given the scale of the intermeshed crises that the planet is confronted with, it is important not to over-emphasize the capacity of the museum in finding solutions. For the same reason, however, it is surely necessary for every institution, in every sector, to reflect profoundly on what its own contribution might be. In order to pursue this more realistic objective and consider what “fields of possibilities” museums, in particular, can make evident and activate, it is necessary to define more precisely what the problem is.

Building on the work of the German historiographer Reinhart Koselleck, Janet Roitman, in her book Anti-Crisis (Citation2013), examines the semantic power of the concept of crisis itself. Regardless of whether an actual state of crisis exists or not, invocations of crisis, she argues, have the function of designating “moments of truth”. These constitute “turning points in history,” moments when “normativity is laid bare … when the contingent or partial quality of knowledge claims – principles, suppositions, premises, criteria, and logical or causal relations – are disputed, critiqued, challenged, or disclosed” (Roitman, Citation2013, pp. 3–4). Following Koselleck, Roitman argues that there is a close association between crisis and critique. Crisis posits a discrepancy “between the world and human knowledge of the world,” between “the real” and what are disclosed as being “fictitious, erroneous, or … illogical” accounts or understandings of the real (Roitman, Citation2013, p. 11). This disclosure of epistemological limitations occasions critique and provokes “a moral demand for a difference between the past and the future,” opening up – at least theoretically – the possibility “to think ‘otherwise’” (Roitman, Citation2013, p. 9). Through crisis, it becomes thinkable that the Ancien Regime can fall; that the epistemological foundations of modernity that are precipitating anthropogenic mass extinction could give way to radically different ways of understanding and sharing the planet.

This, then, is the “epistemological promise” of crisis (Beck & Knecht, Citation2016, p. 61). But, as Joseph Masco warns, while this “affect-generating idiom” has the potential “to mobilize radical endangerment to foment collective attention and action” (Citation2017, p. S65), talk of crisis has become so ubiquitous that precarity has itself been normalized, and the notion of “crisis management” has become a mainstay of the neoliberal state. “In our moment,” Masco argues, “crisis blocks thought by evoking the need for an emergency response to the potential loss of a status quo, emphasizing urgency and restoration over a review of first principles and historical ontologies” (Masco, Citation2017, p. S73). He concludes that “crisis talk without the commitment to revolution becomes counterrevolutionary” (Citation2017, p. S73; see also Fassin & Honneth, Citation2022).

Here, perhaps, there is resonance with that difference in Robert’s and Dion’s vues imaginaire of the museum in ruins. While Robert’s explicitly revolutionary work implies a moral demand for difference between past and future, and envisions a utopian future in the artist’s communion with art in the public gallery, Dion’s dusty vitrine seems to speak only of obsolescence, entropy and decay. In the absence of a vision of, or belief in, an alternative future, its critique of an outmoded order could be said to preserve what it seeks to undo. It is a very museological position, of course: the vitrine itself being an instrument of preventive conservation, acting to slow down processes of change. But is its critique enough? Could we imagine smashing the vitrines – “whose sole purpose,” argues Michael Taussig, “is to uphold the view that you are you and over there is there and here you are – looking … from the outside” (Citation2004, p. 135) – to envision a future founded on an understanding of the profound interconnectedness of all things rather than on the enduring illusion of separation.

In refusing to “manage crisis,” what becomes clear is that the real problem is not biodiversity loss, or climate change, or widening social and economic inequalities. Rather, these are the consequences of a more fundamental crisis of an ontological and epistemological order. As Arturo Escobar argues in Pluriversal Politics: “climate change, the mass destruction of species, and the rapid acceleration of inequality are merely [the] most acute manifestations” of an unprecedented crisis facing humanity (Citation2020, p. 121). “What is in crisis,” he writes, “is the modern liberal … model that has spread over the past several centuries all across the world in its zeal to create a single, globalized model” (Citation2020, p. 121) – a universalist order founded on capitalist logics of expansion, extraction and exploitation.

Colonial epistemicide

It no longer needs stating that colonization entailed not only the seizing of power over territories, resources, and the bodies and labor of people, but also involved the colonization of minds, of languages, of cultural memories, ways of knowing, ways of being (e.g. Fanon, Citation1963; Mignolo, Citation1995). One of the key contributions of much recent decolonial thinking has been to chart this ontological and epistemic “occupation” of subaltern worlds, including the processes of domination through which a “European paradigm of rational knowledge” has expanded into a “universal paradigm,” fundamentally shaping “the relation between humanity and the rest of the world” (Quijano, Citation2007, p. 172; see also Chakrabarty, Citation2000).

It is no coincidence that the Eurocentric “ages” of “Discovery” and “Enlightenment” are regarded by many as marking the start of the Anthropocene in its most destructive, most globally “capitalogenic” guise (Maslin & Lewis, Citation2020; Moore, Citation2018). Witness the devastating impact on human and non-human populations and ecosystems precipitated by European presence in the Americas within a mere hundred years of Columbus’s landfall in the Caribbean in 1492 (Koch et al., Citation2019). Nor is it a coincidence that the modern museum and associated scientific collecting practices were born from this nexus of capitalist/colonialist expansion, part of the same extractive “economy of accumulation,” constituting a “darker side” of the Enlightenment (Mignolo, Citation1995, Citation2011; see also MacGregor, Citation2008).

The accumulation of exotic things – from rocks to plants to animals to human remains and artefacts – and their transformation into geological, botanical, zoological, anthropological and ethnological specimens in the Enlightenment collections of figures such as Elias Ashmole and Sir Hans Sloane, reminds us of the centrality of such “epistemic objects” in the formation of supposedly universal, scientific principles of knowledge in Europe.Footnote3 It is not only that the accumulation of such objects of knowledge was made possible through territorial expansion and so many “voyages of discovery”; rather it is the nature of the knowledge – indeed, the naturalness of the knowledge – constructed from these materials in the emergent institutions of the modern museum, the botanical garden and zoological garden that forces us to acknowledge the link between the “coloniality of power in the political and economic sphere” and the “coloniality of knowledge” (Mignolo, Citation2007; Quijano, Citation2007).

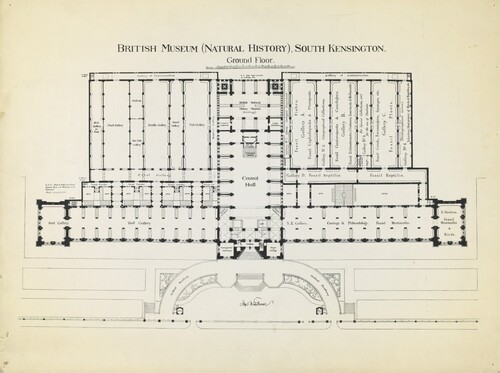

The universalist architectures of knowledge that took form in the eighteenth century – expressed, for example, in Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) – were based on what Escobar terms an “ontology of separation” (Citation2020, p. xiv). This is an understanding of the world constituted by division: human separated from non-human, culture separated from nature, nature divided into hierarchies of kingdoms, classes, orders, genera and species, such as proposed in Linneaus’s taxonomy. Such totalizing knowledge systems would gain concrete architectural expression in nineteenth-century museum design: for example, in Richard Owen’s plans for the new Natural History Department of the British Museum () (Yanni, Citation1996). This hierarchical, classificatory system of difference would be extended to define and determine people, too, according to typologies of race, tribe and ethnicity. Spurious science, substantiated, this time, in the anthropological museum, separating evolutionary degrees of civilization from degrees of primitiveness; forms of knowledge that would justify slavery and genocide, and which still inform logics of socio-economic progress and development.

Figure 3. Floor plan of the British Museum (Natural History), 1872. ©The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

In the museum context, the capitalist/colonialist rationale of this onto-epistemological geopolitics finds its most explicit expression in collections of “economic botany” and “economic geology” in which materials sourced in colonial territories were assembled, organized and displayed not only according to scientific taxonomy, but also in relation to the utility of their distinct physical properties. At the Museum of Economic Botany at Kew, for example, plant specimens (including specimens of barks, fruits, leaves, fibers, resins and tubers) were stored and displayed alongside specimens of “native products” and artefacts derived from the plants, exemplifying the usefulness of their properties (Cornish, Citation2013).

Primary audiences for such libraries of material knowledge included entrepreneurs and industrialists, able to profit from the exploitation of these materials, as well as from the cheap labor available in the colonies to extract these natural resources and produce from them novel goods for international markets. In such ways, museums became significant nodes in a predatory capitalist world-system, implicated in the expansion of monocultural plantations and mining enterprises, for example, with their dire environmental and social consequences.

The European scientific revolution, in which museums and collections played so central a part, was also predicated on separating universally-applicable, empirically-observable, natural laws (for example, concerning the properties of materials) from the mass of vernacular knowledges, customs, beliefs and superstitions. As the Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos argues, this constituted a form of “abyssal thinking,” establishing a “radical line” dividing social reality into two realms, with scientific truth on the one side, and that which was scientifically unascertainable as truth on the other. Modern science was thereby granted the monopoly of determining a universally applicable distinction between truth and falsehood, casting into the abyss alternative bodies of knowledge and understandings of the world that did not accord with its principles of verification and validation (De Sousa Santos, Citation2007, p. 47). As de Sousa Santos claims, “by failing to acknowledge as valid kinds of knowledge other than those produced by modern science,” Western modernity effected “a massive epistemicide,” involving “the destruction of an immense variety of ways of knowing” largely associated with the Global South (Citation2018, p. 8).

The consequences of colonial epistemicide were and are far-reaching. This is not only a matter of cognitive inequality and injustice, in which societies whose knowledge systems have been “suppressed, silenced and marginalised” have been disempowered and rendered “incapable of representing the world as their own in their own terms” (De Sousa Santos, Citation2018, p. 8). What we also begin to recognize is that the crises we now face are themselves products of this epistemicide. As we become increasingly aware of the ecological damage wrought by the globalizing modernity of (neo)liberal capitalism, and the hegemonic knowledge system which underpins it, it is precisely those marginalized ways of knowing, understanding and being in the world that we have most to learn from in envisioning more hopeful futures. Just as we now better understand the importance of biodiversity for sustainable ecosystems, so there is a need to recover greater epistemological diversity and nurture what de Sousa Santos terms “an ecology of knowledges” (Citation2018, p. 8).

The “double movement” of decolonization

According to the Argentinian semiotician Walter Mignolo, the decolonization of knowledge must be understood in a “constant double movement,” involving “unveiling the geo-political location of theology, secular philosophy and scientific reason” on the one hand, while simultaneously “affirming the modes and principles of knowledge that have been denied by the rhetoric of Christianization, civilization, progress, development [and] market democracy” on the other (Citation2007, p. 463). The critical historical work of unveiling the entanglements of power, violence and knowledge has certainly begun to undermine the credibility of modernity’s progressive narratives, but the prospect of a more fundamental epistemic shift capable of unseating the prevailing hegemonic system seems as remote as ever.

Part of the problem is the pervasive and insidious nature of colonial epistemicide itself, which, over centuries, through imposing a singular, universal reality, has excluded the possibility of other realities. As Escobar observes, “It is precisely because other possibilities have been turned into “impossibilities” that we find it so difficult to imagine other realities” (Escobar, Citation2020, p. 3). This is the “abyss” invoked by de Sousa Santos, into which all that exists beyond the pale of objective, rational knowledge “vanishes as reality” and is “produced as nonexistent … not existing in any relevant or comprehensible way of being” (Citation2007, p. 45). Thus, while we may attempt to “unlearn” dominant ways of thinking, it is much harder to imagine how we may retrieve and affirm knowledges and understandings driven into extinction, or to the brink of extinction, not least since established institutions of learning such as universities, museums and archives are so implicated in these histories of epistemic violence.

Unveiling the museum’s complicity in colonial epistemicide, exposing its place in the geopolitics of globalizing/universalizing (Western) knowledge production, is without doubt an important part of the decolonial project. For some, the museum (and especially the anthropological museum) was no less a weapon in nineteenth-century colonial conquest than the Maxim gun, with the consequence that the future of such museums must lie in their being “dismantled” and “repurposed” as “sites of remembrance and conscience for the human lives, environments and cultures destroyed by European colonialism” (Hicks, Citation2020, pp. 11, 228). This necessary focus on addressing past injustice is, however, only half of the “double movement” of decolonization that Mignolo argues for. The question is whether, while acknowledging that museums were and continue to be part of the problem, they may also be part of the solution in relation to the more affirmative, future-oriented dimension of epistemic decolonization.

It is a paradox of European colonialism that the very forces responsible for depleting the global ecology of knowledges of its diversity were also diligent in documenting and collecting the cultural worlds they were making impossible. As the work of colonial modernization and development was implemented through the imposition of laws, the extraction of resources, and the “education” of local populations, anthropologists and ethnologists were busy salvaging the vestiges of “native” life and culture, which they believed were destined to disappear “for ever from the earth before the onward march of so-called civilisation” (Thomas, Citation1906, p. vi). While this anthropological paradigm was heavily criticized by subsequent generations of anthropologists, notably those with more sociological interests, it continued to live on in the museum, the discipline’s institutional base prior to its migration to the university, where its salvaged materials were amassed and organized (Redman, Citation2021; Stocking, Citation1988).

The knowledges produced from these research practices express more about the cultures of colonialism than the societies colonized. However, a by-product of this anthropological zeal for collecting, photographing, recording and documenting the lives and cultures of others was the creation of a remarkable ethnographic archive of alternative ways of being in and knowing the world. This archive survives in dispersed form in museums and other institutions into the present; an ambiguous legacy of colonial science. The question is whether such material and immaterial archives can transcend the colonial circumstances of their making and also become resources for the making of decolonial futures (Basu & De Jong, Citation2016). Is it possible, for example, to acknowledge anthropology’s complicity in violence – epistemic and otherwise – and yet salvage something from its outmoded salvage paradigm to recover and affirm “modes and principles of knowledge” that it participated in rendering nonexistent? Can knowledges consigned to the abyss of the colonial museum and colonial archive be retrieved, reconnected with communities, and reactivated so that they might again exist in a “relevant and comprehensible way of being” (De Sousa Santos, Citation2007, p. 45; see also Basu, Citation2021)?

Pluriversal architectures of knowledge

Of all colonial sciences, anthropology has been most open to the possibility of alternative epistemologies and ontologies. While colonial-era anthropologists rarely expressed doubt in the superiority of their own rationality, they were forced to acknowledge the existence of other rationalities, and the quest to understand how others understand the world became one of the discipline’s primary goals (Malinowski, Citation1922, p. 25). Although couched in terms of “primitive religion,” “totemism” and “animism,” even nineteenth-century field research guides such as Notes and Queries on Anthropology directed the ethnographer’s attention to exploring fundamental questions concerning the nature of being (Tylor, Citation1899). It was accepted, for example, that there was no shared, universal understanding of separation between human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, animate and non-animate. In contrast with Western modernity’s “ontology of separation,” the worldviews encountered by ethnographers, missionaries and other colonial travelers were more often characterized by an ontology of “radical relationality” (Escobar, Citation2020, p. xiii).

If the comparative study of different “worldviews” has been a perennial objective of anthropological inquiry, this has generally been an epistemological question that takes for granted that there is a single world, albeit one subject to a plurality of cultural understandings, explanations and representations. An alternative perspective, most recently pursued by those associated with the “ontological turn” within anthropology (e.g. Henare et al., Citation2007; Holbraad & Pedersen, Citation2017), argues for a more profound understanding of difference: that there are not only multiple worldviews, but indeed multiple worlds; not a singular, universal “reality” subject to a plurality of cultural explanations, but a multiplicity of realities. Such a “pluriversal” perspective calls into question “the hegemony of modernity’s one-world ontology” (Escobar, Citation2018, p. 4) and interrogates its “basic commitments and assumptions about what things are, and what they could be” (Holbraad & Pedersen, Citation2017, p. 5, emphasis in original).

Despite centuries of epistemicide, traces of these other worlds and worldviews survive in particular locations. They linger, for example, between existence and non-existence in the colonial ethnographic archive: materialized in artefacts collections, documented in photographs and moving image, recorded in speech and song, described in fieldnotes and published texts. From the ruins of the universal museum, then, there arises the possibility of contributing to the shaping of a pluriversal future. Until we adopt a position of epistemic humility, however, and are prepared to confront crisis with “a review of first principles” (Masco, Citation2017, p. S73), this is likely to remain a latent possibility and a missed opportunity.

If, on the other hand, we are willing to seize the opportunity and seek to act on these museal and archival affordances (Basu & De Jong, Citation2016), the question arises: How? Echoing the words of Budd Hall and Rajesh Tandon, we might ask: How do we build new pluriversal “architectures of knowledge” to replace the universalizing knowledge architectures that continue to limit our perception of the possible?

How do we “decolonize,” “deracialize,” “demasculinize” and “degender” our inherited “intellectual spaces”?

How do we support the opening up of spaces for the flowering of epistemologies, ontologies, theories, methodologies, objects and questions other than those that have long been hegemonic, and that have exercised dominance over (perhaps have even suffocated) intellectual and scholarly thought and writing? (Hall & Tandon, Citation2017, p. 17)

While Hall and Tandon raise these questions in relation to the need to democratize and decolonize the university, the same questions can, of course, also be applied to the “inherited intellectual spaces” of the museum.

In a similar vein, writing in the wake of the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town, the Cameroonian historian and political theorist Achille Mbembe argues that, “The university as we knew it is dead”. Rather than to continue “living in the midst of its ruins,” Mbembe proposes that we reimagine the university as an institution “capable of convening various publics in new forms of assemblies that become points of convergence of and platforms for the redistribution of different kinds of knowledges” (Mbembe, Citation2015, emphasis in original). Living, as we are, amid the ruins of the universal museum, Mbembe’s proposition, too, could be extended to form a manifesto for the pluriversal museum: a concept of the decolonized museum based on an epistemic architecture of openness, redistribution and reconnection.

Towards the pluriversal museum

If the modern museum was based on “the foundational premises of the separation between subject and object, mind and body, nature and humanity, reason and emotion, facts and values, us and them” (Escobar, Citation2018, p. xiii), what form might a museum based on a notion of radical relationality take? Embracing diversity, the pluriversal museum will surely take a plurality of forms, and, like any institution, it will continue to evolve and transform. We can anticipate, however, that the physical architecture of the universal museum, with its intimidating colonnades, its cavernous, disciplined galleries, its fetishized objects behind glass, its closed-to-the-public off-site stores, will be both inadequate and inappropriate as a space or platform to nurture these new ecologies of knowledges. Instead, it is likely that the pluriversal museum will be:

Less about buildings (especially monumental buildings), and more about people and relationships;

Less about fetishized objects, and more about knowledges, practices, experiences and emotions associated with different kinds of collections;

Less about single-sited centers of accumulation, and more about translocationality, redistributive practices, mobility and multi-sited networks;

Less about curatorial authority, and more about embracing uncertainty and epistemic humility – attending to what we do not know;

Less about pedagogies of telling, and more about pedagogies of listening – attending to and learning from what others have to say;

Less about disciplinary separation, more about the interconnection of different knowledges and ways of knowing – nurturing ecologies of knowledges;

Less about complying with prescribed codes of ethics, more about practicing an ethics of care, based, for example, on attentiveness, accepting responsibility, having the capacities to act and respond – the need to move beyond tokenism;

Less about cultural property, more about fostering a redistributive “global commons” – pooling cultural wisdom to address the common good of human and planetary well-being, while being mindful of histories of appropriation and violence that necessitate a fundamental reconfiguration of power relations (noting that the claim to be “a museum of the world for the world” has be used by the universal museum to maintain the status quo).

This, of course, is not intended as an exhaustive or definitive set of characteristics. Rather, in the spirit of speculation, such a list perhaps helps to turn our attention from “what is” to “what if … ” (Hopkins, Citation2019). What if museums of the future really were characterized by the qualities outlined above? This may be utopian thinking, but confronted with the dystopian prospect of increasing human and planetary “ill-being,” and the rapacious histories that have brought us to this situation, such “dreamscapes” might contribute to what Escobar terms “ontologically orientated design” – design principles that seek to bring about “the political activation of relationality” and participate in “transforming entrenched ways of being and doing toward philosophies of well-being that finally equip humans to live in mutually enhancing ways with each other and with the Earth” (Escobar, Citation2018, p. xi).

Activating the pluriversal affordances of museums

In this essay, I have drawn upon various literatures concerned with epistemic violence, decolonization and pluriversality to reflect upon the possible contribution of museums to addressing contemporary social and planetary crises. As institutions of European colonialist-capitalist modernity, museums are implicated in the histories and structures that have precipitated these crises; they have been and continue to be part of the problem. At the same time, as a consequence of their historical collecting practices, and the regimes of preservation that their collections (including objects, images, sounds, written descriptions, etc.) have been subject to, they offer certain possibilities that could, if activated mindfully and in appropriate ways, also be part of the solution. We might describe these possibilities as “pluriversal affordances” of the museum (Basu, Citation2021, pp. 46–47).

While my invocation of crisis implies that we are experiencing a “moment of truth” – that there has been an epistemological revelation that demands a revolution (Masco, Citation2017) – paradigms shift over decades, even generations. There have probably always been countercurrents to, and within, the prevailing modern, universalist museum in which these pluriversal affordances have been recognized and acted upon. Concepts of the “ecomuseum,” the “relational museum,” the “museum as process,” forms of cross-cultural collaboration and co-curation, are familiar to us in contemporary museum practice and in the museum studies literature (see, for example, Coombes & Phillips, Citation2020; Morphy & McKenzie, Citation2020; Rivière, Citation1985; Schorch, Citation2020; Silverman, Citation2014). We are, it might be said, already moving towards the pluriversal museum.

There is, however, a long way to travel. Much current pluriversal thinking within museums takes place in the context of research collaborations and in the margins of mainstream museum practice, hidden from the public eye. In the meanwhile, where a reconfiguration of museum politics does attract wider attention, for example, in relation to the restitution of African artworks looted in colonial military expeditions, this often merely shifts the location in which collections are physically and semantically imprisoned from national institutions in Europe or North America to national institutions on the African Continent (cf. Sarr & Savoy, Citation2018, p. 39). While such gestures are necessary, these collections remain captives of colonial epistemologies and ontologies in their restituted museum locations in the Global South, incarcerated within a universalist concept of cultural property, the legal title of which has merely been transferred.

The greater challenge – and the greater opportunity – is to set free the ecologies of knowledges, understandings and ways of being that are, in different ways, “archived” in museums; to rescue them from the abyss to which they have been consigned, and to reconnect them with the communities and individuals who have been subjected to, but also have resisted, colonial epistemicide (De Sousa Santos, Citation2018). As we confront the profound damage done by the prevailing global system, including its ontological and epistemological foundations, hope lies in learning to live otherwise. In the greater scheme of things, the power of the museum to effect societal change is limited. If, however, out of the ruins of universalism, the pluriversal possibilities of the museum can be activated, then surely this institution has an important contribution to make in shaping more just and sustainable planetary futures.

Acknowledgements

Originally published in French in Culture & musées 41, pp. 63–91 (2023).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Basu

Paul Basu is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Oxford and Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum. He previously held professorships at University College London, SOAS University of London, and the University of Bonn, where he was founding director of the Global Heritage Lab. Specializing in critical heritage, museum and material culture studies in transcultural contexts, his research draws upon a wide range of ethnographic, historical and participatory methods to explore how pasts are differently materialized and mediated in the present, and how they shape futures. Paul’s research examines the complex ways in which natural as well as cultural heritage is entangled in shifting regimes of value and geopolitical configurations. His work has often involved re-engagements with colonial archives and collections relating to West Africa, exploring their ambiguous status as both sites of epistemic violence and, potentially, resources for communities to recover cultural histories, memories and alternative ways of knowing and being in the world. He recently led the multi-sited research, community engagement and exhibition project Museum Affordances / [Re:]Entanglements (https://re-entanglements.net).

Notes

1 As both the last Keeper of the King’s Pictures under Louis XVI and one of the first curators of the new Musée Central des Arts, Robert occupies an ambiguous position in relation to this museological revolution.

2 There is considerable debate around the concept of the “universal museum”, particularly since the “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” issued by a group of directors of major museums in Europe and the USA in 2002 (see Curtis, Citation2006; Fiskesjö, Citation2014). This declaration drew on the vocabulary of the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention and the concept of “Outstanding Universal Value” as a means to designate heritage “which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity” (UNESCO, Citation2019; see also Labadi, Citation2013). A different genealogy relates to the notion of the “universal survey museum”, defined by the encyclopaedic and totalizing scope of collections and displays, epitomized in the British Museum’s slogan: “a museum of the world for the world”. The totalizing vision of such museums also relates to European Enlightenment ideas of universalism, including principles of rational, scientific knowledge asserted to be of universal validity. According to Hicks (Citation2018), the term “universal museum” was seldom used prior to the late 20th century, and constitutes “a 21st-century charter myth” used by some European museums to justify retaining “collections representative of world cultures”. I am mindful of these various debates and connotations when I use the term in this essay in contradistinction to the proposed notion of a “pluriversal museum”.

3 The collections of Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) were foundational to the establishment of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1683; it was one of the world’s first university museums. Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753) bequeathed his collections to the British nation, leading to the establishment of the British Museum in 1753.

References

- Basu, P. (2021). Re-mobilising colonial collections in decolonial times: Exploring the latent possibilities of N. W. Thomas’s West African collections. In F. Driver, M. Nesbit, & C. Cornish (Eds.), Mobile museums (pp. 44–70). UCL Press.

- Basu, P., & De Jong, F. (2016). Utopian archives, decolonial affordances: Introduction to special issue. Social Anthropology, 24(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12281

- Beck, S., & Knecht, M. (2016). “Crisis” in social anthropology: Rethinking a missing concept. In A. Schwarz, M. W. Seeger, & C. Auer (Eds.), The handbook of international crisis communication research (pp. 56–65). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton University Press.

- Coombes, A. E., & Phillips, R. B. (Eds.). (2020). Museum transformations: Decolonization and democratization. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cornish, C. (2013). Curating science in an age of empire: Kew’s museum of economic botany [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Royal Holloway, University of London.

- Curtis, N. G. W. (2006). Universal museums, museum objects and repatriation: The tangled stories of things. Museum Management & Curatorship, 21(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647770600402102

- De Sousa Santos, B. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review, 30(1), 45–89.

- De Sousa Santos, B. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire: The coming of age of epistemologies of the south. Duke University Press.

- Duncan, C., & Wallach, A. (1980). The universal survey museum. Art History, 3(4), 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1980.tb00089.x

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse: Radical interdependence, autonomy, and the making of worlds. Duke University Press.

- Escobar, A. (2020). Pluriversal politics: The real and the possible. Duke University Press.

- Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. Grove Press.

- Fassin, D., & Honneth, A. (2022). Introduction: The heuristic of crisis: Reclaiming critical voices. In D. Fassin & A. Honneth (Eds.), Crisis under critique: How people assess, transform, and respond to critical situations (pp. 1–8). Columbia University Press.

- Fiskesjö, M. (2014). Universal museums. In C. Smith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 7494–7500). Springer.

- Gould, C. (1965). Trophy of conquest: The Musée Napoléon and the creation of the Louvre. Faber.

- Hall, B. L., & Tandon, R. (2017). Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education. Research for All, 1(1), 6–19.

- Henare, A., Holbraad, M., & Wastell, S. (2007). Introduction: Thinking through things. In A. Henare, M. Holbraad, & S. Wastell (Eds.), Thinking through things: Theorising artefacts ethnographically (pp. 1–31). Routledge.

- Hicks, D. (2018). The “universal museum” is a 21st-century myth. The Art Newspaper, 301, 5.

- Hicks, D. (2020). The brutish museums: The Benin Bronzes, colonial violence and cultural restitution. Pluto.

- Holbraad, M., & Pedersen, M. A. (2017). The ontological turn: An anthropological exposition. Cambridge University Press.

- Hopkins, R. (2019). From what is to what if: Understanding the power of imagination to create the future we want. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Koch, A. C., Brierely, C., Maslin, M., & Lewis, S. (2019). Earth system impacts of the European arrival and great dying in the Americas after 1492. Quaternary Science Reviews, 207, 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004

- Labadi, S. (2013). UNESCO, cultural heritage, and outstanding universal value. Rowman and Littlefield.

- MacGregor, A. (2008). Curiosity and enlightenment: Collectors and collections from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. Yale University Press.

- Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. G. Routledge & Sons.

- Masco, J. (2017). The crisis in crisis. Current Anthropology, 58(Suppl. 15), S65–S76. https://doi.org/10.1086/688695

- Maslin, M., & Lewis, S. (2020). Why the Anthropocene began with European colonization, mass slavery and the ‘great dying’ of the 16th century. The Conversation, June 25. https://theconversation.com/why-the-anthropocene-began-with-european-colonisation-mass-slavery-and-the-great-dying-of-the-16th-century-140661.

- Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://wiser.wits.ac.za/system/files/Achille%20Mbembe%20-%20Decolonizing%20Knowledge%20and%20the%20Question%20of%20the%20Archive.pdf.

- McClellan, A. (1994). Inventing the louvre: Art, politics, and the origins of the modern museum in eighteenth-century Paris. Cambridge University Press.

- Mignolo, W. D. (1995). The darker side of the renaissance: Literacy, territoriality, and colonization. University of Michigan Press.

- Mignolo, W. D. (2007). DELINKING: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of decoloniality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 449–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647

- Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The darker side of western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Duke University Press.

- Moore, J. W. (2018). The Capitalocene part II: Accumulation by appropriation and the centrality of unpaid work/energy. Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(2), 237–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1272587

- Morphy, H., & McKenzie, R. (Eds.). (2020). Museums, societies and the creation of value. Routledge.

- Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

- Quynn, D. M. (1945). The art confiscations of the Napoleonic wars. American Historical Review, 50(3), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.2307/1843116

- Redman, S. J. (2021). Prophets and Ghosts: The story of salvage anthropology. Harvard University Press.

- Rivière, G. H. (1985). The ecomuseum: An evolutive definition. Museum International, 37(4), 182–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0033.1985.tb00581.x

- Roitman, J. (2013). Anti-Crisis. Duke University Press.

- Sarr, F., & Savoy, B. (2018). The restitution of African cultural heritage: Toward a new relational ethics. Ministère de la Culture.

- Schorch, P. (2020). Refocusing ethnographic museums through oceanic lenses. University of Hawai’i Press.

- Silverman, R. (Ed.). (2014). Museum as process: Translating local and global knowledges. Routledge.

- Stocking, G. W. (1988). Objects and others: Essays on museums and material culture. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Taussig, M. (2004). My cocaine museum. Chicago University Press.

- Thomas, N. W. (1906). Editor’s preface. In A. Werner (Ed.), The natives of British Central Africa (pp. v–vi). Archibald Constable.

- Tylor, E. B. (1899). Religion, fetishes, &c. In J. G. Garson & C. H. Read (Eds.), Notes and queries on anthropology (3rd ed., pp. 130–140). The Anthropological Institute.

- UNESCO. (2019). Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Retrieved January 16, 2023, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/compendium/100.

- Yanni, C. (1996). Divine display or secular science: Defining nature at the natural history museum in London. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 55(3), 276–299. https://doi.org/10.2307/991149