ABSTRACT

Under-representation of women in policing is a global phenomenon, with considerable commonality in barriers to career success and differential career experiences compared to men. Through a comparative analysis utilising unique survey and interview data with female and male senior police leaders in England and Wales, this paper considers whether cultural and structural barriers persist and how they are experienced by gender; examines the challenges encountered en route to senior rank; and considers how similarities or differences by gender impact upon careers. The findings are considered to have world-wide relevance, demonstrating that those officers achieving seniority tend to share similar career experiences whatever their gender, particularly at the highest ranks. Leadership styles emerge as homogenous with agentic traits and traditional styles persisting. Costs to achieving higher rank appear to differ by gender however, and access to senior rank is revealed as dependent upon engaging in traditional behaviours including a long-hours culture and ensuring family does not reduce work capacity, effectively promoting a ‘child-tax’ upon female policing leaders. It thus appears that a widespread and global tacit acceptance of policing as a male-dominated profession endures, impacting on female advancement compared to men.

Introduction

Recent research (Garcia, Citation2021) reports that women in policing across the globe continue to have limited representation in leadership ranks compared to men, and that this is exacerbated by the unique barriers faced by women en route to senior positions within the police (Brown et al., Citation2019). In the UK however, forces have asserted that there are no limits in terms of women’s potential success, with claims that macho cultures and stereotypes have vanished, and of gender parity across roles (British Association for Women in Policing, Citation2019). Such claims from within policing (Metropolitan Police Service Citation2020) are however, largely in conflict with the findings of academic researchers (Silvestri, Citation2017, Citation2018, Veldman et al, Citation2017, Brown et al., Citation2019). With a prevailing culture characterised by enduring elements of hegemonic masculinity (Loftus, Citation2009), women in policing in the UK, in line with their colleagues across the globe (Garcia, Citation2021), are found by researchers to continue to face cultural and structural barriers preventing equal career experiences and advancement. A further perennial and worldwide policing problem is centred on leadership (Davis and Silvestri, Citation2020, Caless & Tong, Citation2015). The COVID-19 pandemic and events surrounding the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement have increased scrutiny of what ‘good’ leadership looks like, including a focus on female leadership in times of crisis (Taub, Citation2020) and the relationship between police and communities (Cross, Citation2020). Experiences of senior officers by gender with comparative analysis is therefore a critical and globally significant area of study.

This paper aims to explore the following key question – to what extent do cultural and structural barriers to advancement within the police service in England and Wales persist in policing, and do they differ by gender? In tackling this question, the research will examine the nature of the challenges that females and males encounter en route to senior rank and how these similarities and/or differences impact upon policing careers. It also explores whether increasing proportions of senior women are producing those positive gains that have been associated with female representation, or whether a gendered policing environment protecting the status-quo (Swan, Citation2016) endures. It concludes with recommendations which have implications for future female advancement both within the UK and globally, given the commonality of the female experience (Garcia, Citation2021).

To achieve these aims, this paper first examines relevant literature from across the world on cultural and structural barriers to career advancement, with a particular focus upon machismo, styles of leadership and social constructs of gender. Through analysing extensive primary data gathered from an online survey and semi-structured interviews with senior officers in England and Wales, and secondary data in the form of Home Office statistics and Freedom of Information Act (FOI) requests, it next considers whether and to what extent these barriers remain, and more fully interrogates the gendered career patterns of senior leaders in UK policing.

Cultural barriers to career advancement

Researchers have considered how policing culture and subcultures have evolved, analysing their contemporary features and impact, particularly in relation to attempts to change or reform policing (Loftus, Citation2009, Charman, Citation2017, Davis & Silvestri, Citation2020, Paoline and Gau, Citation2018). Machismo is identified as a specific characteristic of ‘cop culture’ (Bowling et al., Citation2019), with a ‘cult of masculinity’ (Silvestri, Citation2003, p. 22) persisting, and sexual harassment an enduring feature (Brown et al., Citation2018, Garcia Citation2021). This masculine culture can pressurise all officers, regardless of gender, to conform to a macho stereotype, valuing physical ‘crime-fighting’ elements of policing over the more frequently encountered and so-called ‘feminine’ social service aspects (Cochran & Bromley, Citation2003, p. 89).

Navigating cultural barriers has been noted to require ‘complicity’ from both women and men in supporting the macho status-quo (Silvestri, Citation2006, Abrams, Citation2012), including total job-commitment and ambition for power; for women, this extends even to the point of accepting ‘motherhood may be incompatible’ (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 277). Furthermore, while pervading gender norms can be detrimental for both women and men (Angehrn et al., Citation2021), for women who do not subscribe to macho norms, there is a dual credibility challenge of being both female and trying to operate outside of cultural norms (Davis & Silvestri, Citation2020); thus women can be marginalised from wider policing activities and encounter a limited portfolio, inhibiting career progression.

In terms of leadership, ‘successful’ leadership has long been stereotyped in masculine terms (Saint-Michel, Citation2018), and linked to transactional leadership styles (Schein, Citation1973). More recently however, studies have suggested a significant shift, with the more ‘feminine’ transformational style of leadership, “characterized by collaboration, inter-personal interactions and power-sharing’ (Saint-Michel, Citation2018, p. 945)being highlighted as most likely to overcome obstacles to change, particularly the limiting nature of organisational culture (Cockcroft, Citation2014). While transactional leadership has its place (Tucker & Russell, 2004), transformational approaches are claimed to promote change, influence followers’ mind-sets, and encourage acceptance of change and innovation (Silvestri, Citation2007).

However, an analysis of continuing crises of police leadership and repeated failures to implement enduring change suggests that attempts to operate as a transformational organisation are yet to succeed in policing, and instead macho transactional styles persist (Rowe, Citation2006, Golding & Savage, Citation2008). This also appears to be the case in other organisations more widely, and consequently, the notion of the more feminine transformational styles of leading which are associated with reform and success, has not translated into parity of senior appointments by gender, with women still significantly under-represented and occupying less than a third of the UK’s top positions (Marren & Bazeley, Citation2022).

There is also a need, however, to be mindful of reinforcing stereotypical notions of women and men leading in opposing ways with popular commentary suggesting that women favour transformational leadership styles and men more transactional styles. Österlind and Haake (Citation2010) for example, found considerable variation in leadership preferences within gender groups, and noted the impact of organisational context. Observing police leadership styles to be predominantly ‘masculine’ is not the same as saying all males lead in a transactional way, or all women leaders prefer participatory approaches; constructs of gender, rather than biological differences are equally relevant.

Structural barriers to career advancement

Beliefs around differing traits by gender appear strongly held by both women and men, and are reproduced within organisations to the disadvantage of women in particular (Stemple et al, Citation2015; Cislaghi and Heise, 2019). Men are often associated with agentic characteristics, such as ‘aggressive, ambitious … and prone to act as leader’, while women are assigned communal attributes, for example, ‘affectionate, helpful, kind’ (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002, p. 574). Where individuals do not fit expected gender norms, role incongruity is frequently perceived and, in policing, can help explain resistance towards women officers, particularly in roles considered more ‘masculine’ such as firearms (Cain, Citation2011). It can also indicate why women officers may still gravitate towards roles traditionally undertaken in greater proportions by women, such as supporting sexual abuse victims or community-oriented policing (Haake, Citation2018), and why senior women are especially vulnerable to sexual harassment, being perceived as threatening the ‘gender hierarchy’ (Brown et al., Citation2018, p. 3). Conversely, there is evidence of men being likely to be less attracted towards those roles more traditionally associated with women, both in policing (Gaston & Alexander, Citation1997) and other organisations, with omnipresent and dominant masculinity norms shaping their choices (Abrams, Citation2012, p. 565)

For women in policing, the impact of these gender norms becomes particularly evident when balancing shift-work, long hours and families; even when having police partners, women are most likely to take primary responsibility for organising child-care, with part-time working considered still their preserve (Gaston & Alexander, Citation1997, Bury et al., Citation2018).

Women have also been observed to get ‘left behind’ in organisations if they do not get promoted quickly (Haake, Citation2018). Not applying for promotion; not taking opportunities presented; specialising for significant periods of time; or even just being indecisive, can limit advancement within the span of a police career (Gaston & Alexander, Citation1997; Drew and Saunders, Citation2020). Thus in policing, taking longer than men to reach the first-level supervisory ranks is just as likely to limit women’s progression as any ‘glass ceiling’.

The impact of marital and parental status is another internationally recognised barrier affecting the career progression of more women than men in policing (Rabe-Hemp, Citation2008, Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009, Ward and Prenzler, Citation2016). In policing, ‘the doing and managing’ of time (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 266) establishes organisational commitment and credibility, with those officers trying to balance work and family through part-time working at risk of finding themselves perceived as ‘part-able, part-committed and part-credible’ (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 274). However, even working full-time may not be enough in senior ranks where extreme hours are expected (Turnbull and Wass, Citation2015).

The global literature thus highlights clear cultural and structural barriers to career advancement in policing, and how they affect women and men differently. What this paper seeks to do is to explore the extent to which such barriers to advancement within the police service in England and Wales persist, and in doing so, examiners the challenges women and men encounter en route to senior rank face, and considers how these similarities or differences by gender impact upon policing careers. The paper concludes with suggested policy changes that have the potential to reduce such barriers and challenges.

Methods

This research utilised both primary data (survey and interviews) and secondary data (analysis of Home Office statistics and FOI responses from police forces). The Home Office police workforce data provide annual information relating to the demographic composition of forces in terms of rank and gender; however, it is limited in the range of data sets produced. In the absence of any other centralised data available to assess the promotion processes to each rank by gender, FOI requests were utilised to facilitate the collation and comparison of information considered significant in terms of the research question.

Primary data was derived from a comprehensive and largely quantitative anonymous online survey, widely distributed to female and male senior officers (superintendent and above) in Home Office police forces in England and Wales. The survey was ‘routed’ in order to facilitate more effective navigation through the questions depending on a respondent’s personal circumstances, i.e., if they had no children, no further questions about children/child care arrangements would be encountered by them. Appendix A summarises the areas addressed by the survey.

FOI and survey responses were coded and analysed as nominal data using IBM SPSS software. Probability calculations (p) were derived from Pearson’s chi-square statistic; where p < 0.05, there is a 95% probability the relationship did not occur by chance, rising to 99% where p < 0.01.

The survey was followed-up by semi-structured telephone interviews with 30 senior officers, allowing for a more in-depth and qualitative exploration of career experiences, including barriers and opportunities, personal circumstances, and leadership styles. Appendix B provides a summary of the themes explored in the semi-structured interview. Transcribed interview responses were coded and integrated into themes and concepts, providing substance and underpinning survey findings with personal accounts.

Limitations

It is recognised that the research methodology has a number of potential limitations. In particular, some issues were experienced with the distribution of the on-line survey, with one larger force’s security systems initially blocking access. While this access issue was subsequently addressed, it was noted that response rates in that force were proportionally less than in those where the survey was able to be accessed at first circulation. The survey also relied on force systems correctly identifying all eligible respondents. It is important to acknowledge the impact of non-returns on research validity as it has the potential to create a biased sample (Moutinhou & Evans, Citation1992). It is contended here that such bias is likely to have been mitigated by the overall number of respondents and forces represented; however, future studies could benefit from more robust testing of the survey link in all forces, prior to final circulation.

With regards to the telephone interviews, these relied on respondents to the main survey putting themselves forward to participate in a semi-structured telephone interview; 32 volunteered, with 30 still being available when the interviews were arranged. As interviewees were not randomly selected, this risked introducing a degree of bias into the findings, with those agreeing to be interviewed potentially being motivated to do so by their specific personal experiences. While it is proposed that the mixed-methods approach taken for this research, allowing for triangulation across the methods used, should provide confidence in the validity of the findings (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner, Citation2007), future research might benefit from further consideration of employing a more random sampling method for the semi-structured interviews.

It should also be noted that this study focuses on the experiences of senior officers and does not provide a comparative analysis of those officers who have not (yet) achieved senior rank. The literature reviews, secondary data, and experiences of interview participants allow for some comparisons and conclusions to be drawn, but conducting the same research across all ranks would be a fruitful approach for a future study.

Findings

Analysis of Home Office police workforce data 2000–2019

The Home Office publish police workforce data annually. Each publication between 2000 and 2019 was analysed and revealed significant disparity in gender representation across forces. With an ‘unprecedented’ significant uplift in police officer numbers commencing in 2020 (Home Office, Citation2019b), including figures beyond 2019 was considered to have the potential to skew data and impact on the accuracy of longer-term trend analysis. Although the proportion of female officers continues to grow annually, comprising 30.4% of police officers in England and Wales (Home Office, Citation2019a), rates of growth have slowed and this under-representation attracts little comment (National Police Chiefs’ Council, Citation2018). While 2000–2010 saw female officer numbers increase 9.2% (to 25.7%), the following nine years saw less growth, increasing by just 4.7%. This trend was predicted (Brown & Bear, Citation2012), and follows a history of ‘progression and regression’ (Silvestri, Citation2015, p. 59). With budget cuts reducing overall police numbers (Brown & Bear, Citation2012), there were just 1.2% more female officers at March 2019 (37,428) than at March 2010. Women officers also leave policing in higher proportions than men, with 34% of female leavers exiting through voluntary resignations in the 12 months to March 2019 compared to just 22% of men (Home Office, Citation2019a, p. 32). Furthermore, the proportion of female constable joiners in 2019 (34.7%), remained virtually unchanged for over a decade (33.9% in 2008).

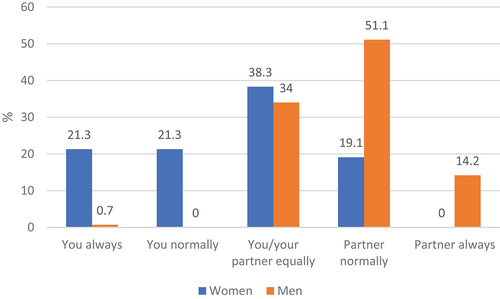

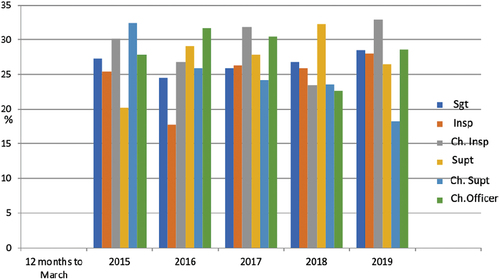

Home Office data indicate female representation of all officers at superintendent level and above has increased four-fold (6.1% to 26.4%) since the start of the millennium, doubling since 2010 (Home Office Citation2019a). However, deeper analysis of female promotions in the five years to March 2019 (see ) indicates rates plateaued, and the overall rise in their share of senior ranks is more likely due to a greater proportion of male retirements than increases in female promotions (i.e., historically, the proportion of superintendent posts held by men was even greater, and as they retire, the size of the female share of all posts increases). For example, all senior ranks saw a smaller proportion of female promotions in the 12 months to March 2019, compared to March 2016. It is thus contended that, without significantly more women recruited, there will not be any sustainable increased representation of women in all leadership roles.

Figure 1. Proportion of promotions that were female 2014–19 Home Office forces: England and Wales (Source: Home Office, Citation2019c).

Secondary data: analysis of police force Freedom of Information Act responses

With no centrally collated information enabling gender comparisons of promotion applications and success, FOI requests were made to all Home Office forces to obtain this information. Sixteen forces supplied at least some of the requested data, which represents over a third of all Home Office forces, thus allowing for meaningful conclusions to be drawn. The emergent key themes in relation to promotion examination and boards plus temporary promotions are analysed below.

National examinations must be passed before officers can apply to a force’s sergeant or inspector promotion process. Eight of the responding forces were able to provide this data, which revealed 2,414 officers applying to sit the sergeants’ examination between 2015 and 2018 (); women are more likely than men to withdraw from the examination process (p < 0.01); and there is no significant gender difference in pass rates. With regards to officers sitting the inspectors’ examination between 2015 and 2018, data relating to 1,041 applicants was supplied (). Considering applicants had to already be a sergeant to take the inspectors’ examination, no notable difference between men and women was found in terms of the proportions applying for, withdrawing, or passing the exam. Over these three years, women averaged 23.4% of applications to sit the exam and 25.6% of those passing.

Table 1. Application & pass rates for the qualifying examinations to sergeant 2015–2018

Table 2. Application and pass rates for the qualifying examinations inspector 2015–2018

Unlike the national examinations, selection processes are set independently by forces, and differ across forces and ranks. Consistent with previous observations regarding women’s reluctance to apply for promotion to sergeant (Rabe-Hemp, Citation2008, Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009), the FOI data show women pass sergeant examinations in similar proportions to men, but do not apply for actual promotion boards to sergeant in proportionate numbers (). Between 2015 and 2018, the share of applications submitted by females fell from 27.8% to 21.2%; this potentially helps explain Home Office (Citation2018) data which reports lower proportions of female sergeants nationally.

Table 3. Force applications & pass rates for promotion to sergeant 2015–2018

However, based on 985 male and female applications between 2015 and 2018 for inspector rank, and 484 for chief inspector (), women do appear to be applying for promotion to inspector and chief inspector ranks in proportions consistent with the eligible numbers of their gender.

Table 4. Force applications & pass rates for promotion to inspector 2015–2018

While there was no evidence of differential success for women in promotion to superintendent, women were consistently less successful than men in the chief superintendent promotion process, despite applying in proportionate numbers (). This is particularly notable, as Home Office data (2018) also shows a decline in female promotion rates to chief superintendent since 2014.

Table 5. Force applications & pass rates for promotion to superintendent 2015–2018

In a further area of concern, the FOI returns revealed that women emerged as being proportionately less likely than men to have a temporary promotion (). Of 1,656 reported temporary promotions across all ranks between 2015 and 2018, just 330 (19.9%) were to women. With an absence of academic or police research into how these promotions are awarded, and the potential advantage they bring for career advancement, the selection and impact of temporary promotions is proposed as an area for further research.

Table 6. Force Temporary promotions between 2015 and 2018

Primary data: analysis of online survey and telephone interviews

The rank and gender of the 231 survey participants is detailed in . The 30 volunteers (14 women and 16 men) who engaged in telephone interviews comprised 21 superintendent-ranked officers and 9 chief officers (). Responses for ‘superintendents’ include combined responses from superintendents and chief superintendents, while those from ‘chief officers’, combine responses from ACCs, DCCs and chief constables, and their equivalents. ‘Senior officers’ indicate all of these ranks combined.

Table 7. Rank and gender of survey respondents

Table 8. Rank and gender of interview participants

Based on workforce data at the time of collation (Home Office Citation2018), the number of survey participants represented 14.6% of all those serving as superintendents, and 24.7% of all chief officers. All chief officers identified as white British, and just one female superintendent and four male superintendents identified as BAME (2.8%). Most men self-identified as heterosexual, with only one male identifying as gay, and three preferring not to say. Thirteen (16.5%) females identified as gay or lesbian and three preferred not to say. With around 2% of the UK population identifying as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) (Office for National Statistics, Citation2019), it appears the proportion of gay and lesbian women in senior officer posts may be higher than the reported number of gay and lesbian women in the general population.

Meanwhile, it could be suggested the absence of senior male officers identifying as gay supports other studies indicating that being gay and senior in rank may attract discrimination (Jones Citation2015). While Jones identifies career costs in disclosing an LGB identity in policing, this study indicates that ’promotion-costs’ are greater for male LGB officers; McGinley (Citation2013, p. 799) suggests ‘women who emulate men can be forgiven’ while men who challenge the masculinity of other men are considered ‘traitors’ for weakening their hold on power. For policing, this is a fruitful area for further study.

The aim of this paper was to explore the extent to which cultural and structural barriers to women’s advancement within the police service in England and Wales persist; thus, the analysis of the survey and interview responses along the themes of those barriers have been considered and are discussed below.

Cultural barriers

‘Fitting in’

Social identity and ‘acceptance’ are considered important aspects of organisational culture. Early experiences and how police officers settle and feel valued on joining is considered particularly significant (Charman, Citation2017), and ‘being accepted’ emerged as a key feature during the interviews. Responses highlighted that, particularly in their probationary years, most senior officers (28 interviewees) encountered a macho culture, and felt the need to prove their worth, usually by way of demonstrating ‘physical fortitude’ (male superintendent) or ‘getting stuck in’ (female superintendent). Understanding the ‘pecking order’ and making tea were considered by most as essential factors in fitting in; yet while responses were similar by gender, only women (six) commented on how long they were expected to make the tea for, suggesting women may have been subjected to a longer period of ‘initiation’ before being accepted:

I was the only female on our shift … I was the person who brewed up for five years. Every single brew. (Female superintendent)

Interviewees also described how with each new role the challenge of ‘fitting in’ recommenced. Generally, a drinking culture was considered part of being accepted:

I went out to prove myself completely, so long hours working, … quite masculine stuff like going out … drinking pints, stupid stuff. (Female superintendent)

Even at senior officer level, one chief officer described how easy it was to be considered ‘an outsider’ if you did not concur with the cultural norms:

I found the (Senior Command Course) quite difficult because I got a syndicate who were really sociable and drinkers and I am not either of those things. … so this notion of making friends and colleagues for life … did not really happen for me. (Male chief officer)

Hostile behaviours

Considering the common experiences shared by those who are now senior officers provides some insight into the extent of the challenge for policing to deliver reforms and for senior leaders to lead differently. Those who resist the culture become ‘other’, and while many interviewees did give examples of trying to confront negative practices or behaviours, such interventions often met with resistance even at the highest levels, or led to the challenger being forced to move on. One male superintendent disclosed losing a promotion simply for questioning the extent of the commute:

He (the chief constable) said ‘look, you’ve pissed me off … so you are not going to get promoted, we are cutting back’.

Even in chief officer ranks, senior officers can be subject to transactional leadership styles and intolerance towards challenge, with one male chief officer explaining how he found himself moving forces several times to escape ‘monsters in senior positions’. When asked if he felt if there were still such people, his response was clear:

Definitely, just look what is happening … swearing, bullying. I think at chief officer level there is a terrible lack of challenge and lack of choice for the top jobs this is a real crisis in policing.

Although most interviewees commented to the effect that ‘things are different now’, their emerging accounts across all ranks and genders remained littered with evidence of persistent negative cultural elements. Over half (eight) of the women interviewed highlighted perceptions that being female had negatively impacted on their opportunities for promotion.

My gender has always been a factor in my progression… My competence is always questioned whereas male officers do not experience the same level of scrutiny. (Female superintendent)

While discussing their career experiences, instances of sexual discrimination and harassment were regularly cited by the women officers interviewed:

I got on with (my colleagues) really well. They all tried to get off with me … they saw me as a bit of a conquest …They used to watch porn on the night shift where we had our sandwiches, I used to sit by myself. (Female superintendent)

In line with the findings of Brown et al. (Citation2018) such hostile behaviours appeared frequently in the accounts given by women, with 10 women citing specific examples. While most males generally consigned such behaviours to history, for women, such incidents emerged as a more enduring and contemporary feature of their experience, even when they achieved more senior positions:

I was a (detective inspector) … and at a Christmas do the superintendent was absolutely drunk … telling me what he wanted to do with me and a female sergeant in most graphic detail, and he was head of complaints! … I had a really torrid time when I was on the murder team as a (detective chief inspector) …it was all gender related … and when I got put forward for promotion to superintendent I was told ‘I’m only doing it because I have to have a woman on my list’. (Female chief officer)

This same woman asserted there was still work to be done in addressing these issues:

What I find upsetting is some of the comments that I heard as a female when starting 25 years ago are still being said now. (Female chief officer)

In responding to harassment and discrimination however, female interviewees demonstrated the resilience associated with career success for women, not just by remaining in policing and achieving senior rank, but also by trying to ensure that the unfairness they had faced was addressed in some way, even if at a later date.

From the interviews, it was clear that bullying and harassment still continues to undermine both women and men even in senior ranks. While many challenged the culture, others were concerned about how easy it was to acquiesce, with one male superintendent expressing regret for having engaged in a ‘womanising’ culture, and the effect it had on his marriage:

I was a dick, there is no doubt about it … The culture I got into was one of ‘this is normal, you need to be a player if you want to get on, you need to be seen as one of the lads.

Time served

This research found evidence that the structural impact of policing and time taken to navigate the hierarchical police rank system continues to present a gender-bias. Combined with cultural features connected with time, e.g., over-time, on-call requirements, and negative perceptions of flexible-working arrangements, this inhibits the career advancement of women officers in particular.

While finding no notable difference in terms of overall length of service by gender for those in senior officer ranks (almost 90% of female officers and 86.5% of male officers had at least 20 years’ service, and just over half of female officers and 56.3% of male officers had at least 25 years’ service), this research did find that speed through the earliest ranks of constable, sergeant and inspector, tended to be positively associated with progression to chief officer positions, and was statistically significantly at the first inspector rank ().

Table 9. Speed through early ranks by % rank and gender

When considered against a tendency for women to be more reluctant than men to apply for a post unless they are certain they meet all essential and desirable criteria (Mohr, Citation2014), and evidence from the secondary data that, generally, women do not apply for the first rank of sergeant in the same proportions as men, finding ways to increase the confidence of female constables to apply for fast-track opportunities and assisting women in preparing for the sergeant promotion process could therefore help increase the proportions of women who subsequently achieve senior posts.

Around half (16) of the interviewees commented on the cultural element of having to serve enough time before a promotion or posting was considered justified by others, and how opportunities could be lost because of this:

Length of service is discussed a lot in policing … often the term credibility is linked to length of service and I disagree with that. (Male superintendent)

‘The boys club’ still exists and you have to earn their respect and move through the pecking order … you don’t get promoted on skills. (Female superintendent)

In this study, the issue of how time is used during a policing career was explored during interviews, and the survey asked senior officers to identify their hours worked and to report on any flexible working patterns or career breaks.

From the survey, part-time working for child-care/other caring reasons emerged as something 17 female superintendents (31.5%) had undertaken during their careers; demonstrating it is possible to work part-time for at least some period during service and still achieve senior rank. However, only two male superintendents had ever worked part-time in policing (p < 0.01) and, among chief officers, only two females (8%) and one male had done so. The proportion of female superintendents compared to female chief officers working part-time was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Even for those who had engaged in part-time work, it had not been without challenges, with interviewees reporting a need for them to be flexible, rather than the organisation.

While one chief officer had not herself worked part-time, her male partner had done so, and his reported experience suggests negative attitudes expressed may be about working part-time, rather than gender:

The things that I hear women talk about in terms of confidence in terms of part-time working, and people thinking you are shirking and people stereotyping, he has suffered all of that as a male. (Female chief officer)

Based on self-reported working hours, the majority of superintendents surveyed generally worked in excess of 50 hours a week. The proportion of male superintendents reporting these hours (74.4%) was statistically greater (p < 0.05) than women (57.4%). A similar gap emerged for superintendents working over 56 hours a week, with 46.3% of men reporting such hours compared to 27.8% of women (p < 0.05). Among chief officers, there was no difference by gender with the majority of both males (72.4%) and females (68%) typically working in excess of 56 hours a week. Chief officers worked significantly longer hours than superintendents (p < 0.05), with 58.5% of male chief officers and almost 25% of female chief officers reporting a working week in excess of 60 hours (see ).

Table 10. Average hours worked per week by % rank and gender

In interviews, most participants (25) referenced a need to work excessive hours, and many expressed concern about the negative impact on health and family. It was also acknowledged such hours were not good in terms of how the chief officer rank was perceived, and some superintendents reported that the thought of working even longer hours reduced their desire to apply for promotion to chief officer.

Typical observations regarding hours worked included the following:

I went to my supervisor and said, ‘ … , I can’t continue like this’ … He said, ‘Well nobody gives a fuck, you’ve just got to get on with it.’ (Male superintendent)

As I write this, it is 8 pm and I came in at 6am. I want to love my job. I currently hate it. I cannot leave it because I am four years from retirement – otherwise I would go tomorrow.’ (Male superintendent)

The long hours is the biggest strain … you know you are not always a good role model, but I don’t see how I could do the job otherwise, and I’ve no children to manage. (Female chief officer)

Structural barriers

The findings from both the online survey and the telephone interviews suggest managing childcare and family time remains a significant impediment particularly to the career advancement of women with children. Comparing responses across ranks and not just gender highlights how concerns about juggling family responsibilities is a key factor in preventing women accessing the highest ranks. To achieve promotion success, both men and women with children have to make choices and sacrifices, although these choices and sacrifices manifest themselves differently.

Across all ranks, most survey participants (91.4%) were married or cohabiting, with no significant differences by rank or gender. A striking proportion of married/cohabiting women (85.7% compared to just 20.4% of males (p < 0.01)) reported that their current partner was a serving or former police officer. This appears even higher than identified in previous research studies (Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009), and which have highlighted additional issues experienced when both partners are subject to shifts, particularly when childcare arrangements need to be made. Although evidently, with women comprising under 30% of those serving in forces, in terms of opposite-sex relationships, men would be less likely to be married to a female colleague than vice versa, the high proportion of senior women married to a current or former officer may indicate that a relationship with someone who has experienced policing is an ‘enabler’ for the career advancement of women into senior positions.

Around 75% of both genders with partners reported partners being supportive of them being police officers. Noting partner-support for women as police officers increased with service, Alexander (Citation1995) considered whether this might be due to partners changing their attitudes, or women officers changing their partners. This study potentially answers that question, as senior women officers were twice as likely as men to have had a change of partner, and almost 70% of women compared to around 35% of men, reported the break-down of a serious relationship during their police service.

Asked whether partners encouraged them to apply for further promotion, differences emerged by both rank and gender, indicating partner-support is relevant in achieving the highest ranks, particularly for women. 62.2% of females, compared to 45.3% of male superintendents agreed or strongly agreed their partners encouraged them to apply for the next rank (p = 0.06). Among chief officers this support did not differ by gender (80% of female chief officers and 82.8% of male chief officers felt encouraged), but was significantly higher than among superintendents (p < 0.01).

The survey findings with regards to personal relationships accords with those found in previous research (Silvestri, Citation2006, Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009), suggesting that the domestic environment for senior officers remains relatively unchanged over the last few decades. For example, with reference to the employment status of partners, 58.2% of senior women compared to just 36% of men (p < 0.01) reported having a partner working full-time. Conversely, very few women (3.8%) reported having a partner working part-time, compared to 42.7% of men (p < 0.01). With regards to having children, no difference by rank was found, but there was a significant difference by gender, with 59.5% of women compared to 94.5% of men (p < 0.01) having children. The number of children male and female participants had also differed significantly (p < 0.01), with 31.9% of women with children having one child, compared to 8.5% of men; and 39.8% of men having three or more children, compared to 12.7% of women.

The evidence here suggests that, unlike their male counterparts, women in policing feel less able to combine work with children, or at least with larger numbers of children. With 42.6% of senior women with children reporting having taken on the main responsibility for making childcare arrangements compared to only one male (0.7%), having children clearly impacts on senior women differently to men () with the potential to affect their career decisions.

Generally the effect, however, was felt greater at superintendent rank than at chief officer rank (see ) with a significant proportion (36.4%) of female superintendents feeling they would have achieved higher rank without having had children, compared to just one female chief officer with children (p < 0.01). Furthermore, just over half of female superintendents (51.5%) compared to around a third (34.5%) of male superintendents with children (p < 0.05), felt they would have achieved their current rank sooner if they had not had children, while only two (14.3%) female chief officer and one male chief officer with children reporting to have felt this to be the case.

Table 11. Impact of having children on careers: % of those with children by rank and gender

While female superintendents were the most likely to feel held back in their careers by having children, conversely evidence emerged of male superintendents being more likely to consider children as a motivating factor for seeking promotion, with 35.7% feeling such motivation compared to only 9.1% of female superintendents (p < 0.05); this is potentially due to the pressure of being the main earner, given the evidence their partners were more likely to work part-time. There was no difference between chief officers by gender in this regard.

Thus, a picture emerges indicating gender and social identity may be key factors for men as well as women in terms of the rate of their career advancement.

Throughout the interviews, the impact of family life was a recurring theme and supported the survey findings. Managing family life was challenging, and largely achieved with family and partner support, with three women specifically acknowledging they had limited family size to help manage their careers. Where male partners were providing childcare, this was due to them either being retired and having the flexibility to be more involved, or acknowledged as being at a cost to their own careers.

Most male senior officers (12) expressed their appreciation of partners who worked part-time, or had not pursued their own career ambitions, in order to allow them to pursue theirs. One superintendent described himself as ‘forever indebted’; others acknowledged the cost of time with families.

My wife went part-time when we had children and now doesn’t work at all. We made financial sacrifices to achieve this … but I really think it was worth it, so that I could put the hours in at work and get promoted … , although it does mean I saw less of them growing up than I might otherwise have done. (Male superintendent)

Despite role congruity theories associating males with agentic characteristics (Saint-Michel, Citation2018), it is proposed that what does not emerge from these interviews is an image of ambitious men pursuing career advancement with no thought for the impact on their families or their partner’s careers. Rather, negotiated and agreed positions are discussed, with recognition of what partners might otherwise have achieved. The survey responses, however, indicate that unlike their female counterparts, male desire or success in achieving senior positions is not affected by family size.

Discussion

The central themes which have been taken from the research findings relate to both cultural and structural barriers facing women (and to an extent some men) en route to leadership positions. The cultural barriers are seen in relation to ‘fitting in’, hostile behaviours and a time served culture which rewards excessive working hours and a commitment to full-time work. The structural barriers focus much more upon the challenges of managing child-care and family responsibilities where that burden of responsibility falls much more heavily on women. It is evident from this study that experiences of senior police officers by gender do differ across many aspects, while they share similarities in others. What is particularly apparent is that differences between male and female chief officers are less pronounced than those between male and female superintendents, with ‘sameness’ being a clear factor in achieving the highest police echelons.

Focussing on competencies and personal qualities, female and male leaders generally exhibited more similarities than differences, and while leadership styles aspired to were largely transformational, the reality revealed many examples of transactional leadership styles. In the survey, where differences were evident, these echoed other research (Ergle, Citation2015) suggesting women leaders may in fact be more likely to demonstrate agentic characteristics than men. Given the resilience required to address issues of role congruity; discrimination, and bullying or harassment; the more macho elements of police culture (Loftus, Citation2009); and the association between leadership and masculinity (Braun et al., Citation2017), it is hardly surprising to find the highest-ranking women in policing today still tend to have, or to have adopted, more masculine gender identities (Swan, Citation2016). As Cockcroft (Citation2014, p. 6) observes, despite working their way up through the ranks, senior officers are ultimately ‘cut from the same cloth’ as the rest of the police organisation, and in gaining acceptance often adopt similar behaviours. Evidence thus emerges of female chief officers’ career histories being more similar to those of their male peers rather than those of female superintendents. Whether consciously or not, female chief officers are less likely than female superintendents to have performed roles considered congruous with their gender (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002). It appears, like the early pioneers identified by Maddock (Citation1999), either those women with the skills to become chief officers behave like, and choose similar career paths to, male officers, or the behaviours and experiences of those choosing such paths are more likely to secure promotion to the highest ranks.

Either way, these findings indicate chief officers, regardless of gender, share very similar and traditionally ‘male’ career experiences, according with notions of ‘ideal’ workers and leaders (Acker, Citation1989, Silvestri, Citation2018). It is contended that the extent of this commonality in force executive teams is likely to lead to homogeneity in approaches, with the potential to stifle cognitive diversity and promote conformity with masculine prescriptions regardless of gender (McGinley, Citation2013). This has the potential to undermine those advantages which have been linked with diverse teams in successful organisations and their ability to manage the desired change and reform in policing (Jones, Citation2015).

Generally, both male and female participants shared similar desires and early career experiences in terms of steps taken to ‘fit in’ and achieve job satisfaction through group acceptance (Metcalfe & Dick, Citation2002). Similar to Charman’s (Citation2017), the accounts provided here suggest a ‘re-navigation’ from outsider to insider with each new posting and team joined, regardless of gender or rank. A social need for group acceptance where traditional policing cultures still endure (Loftus, Citation2009), means police leaders may also be repeatedly required to pit their personal values or preferred leadership styles against the status quo. Where ‘difference’ goes beyond just wanting to do things differently, such as being a woman, the battle for acceptance without compromise is magnified.

One particular area for concern around conforming to dominant cultures is the extent of sexual harassment and inappropriate behaviours revealed in these interviews, which raises questions regarding how such prevailing dominant cultures hinder change initiatives and police reform. It is possible these types of behaviours and situations are contributing to the higher premature exit rates of women officers compared to men (Brown et al., Citation2018). They are also likely to impact negatively on the wider perceptions of policing as an attractive career choice for women (Brown et al., Citation2018). While men often reported instances of bullying, threats towards women and sexual harassment in particular appear more frequent and ominous given their adverse impact on mental health (Angehrn et al., Citation2021), the degree of resilience required to survive these experiences while still achieving career advancement, is arguably greater for women than for men.

Both survey and interview responses illustrate that for chief officer, and in particular chief constable posts to be achieved, the need to speed through all ranks remains as relevant as ever (Reiner, Citation1991). Managing this in a culture that values ‘time served’ can be challenging for men and women alike, and requires specific interventions, such as access to fast-track systems, or support from others, to off-set wider organisational criticism for seeking promotion outside of ‘normal’ timescales. This is before the impact of needing any time out is considered, which in terms of maternity leave will naturally impact on women rather than men. Balancing personal responsibilities with work, particularly childcare roles, has been highlighted as a major barrier for the career advancement of women in policing (Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009) and indeed in the wider world of work (Acker, Citation1992).

Raising children affects time in the workplace for women more than it does men (Brown & Bear, Citation2012). Balancing children with work has been described as an ‘irresolvable conflict’ for senior women in policing (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 273), and this study, like Banihani et al. (Citation2013), found that, despite strengthened legislation and family-friendly policies (Woolnough & Redshaw, Citation2016), reconciling work and family life is still experienced differently by gender for senior officers. Other studies observe that the larger the family size, the greater the negative impact on women’s career progression (Cools et al, Citation2017), particularly in countries like the UK where parents are predominantly reliant on paid arrangements or family for childcare. While other studies have identified ‘marriage tax’ limiting women’s careers (Archbold & Hassell, Citation2009), this study indicates that many senior women may have paid a ‘child-tax’, as unlike their senior male colleagues, they are likely to have either no children or smaller families. This is not to say senior women regret their choices regarding having children or family size, or that they consciously made them to achieve career success, although a small number did raise this as an issue. Asked to indicate on a scale from ‘strongly disagree to strongly agree’, more women than men felt that they had managed to balance their family and work life successfully, with 53.2% of female senior officers agreeing that they had done so, compared to 35.5% of men (p < 0.05).

How officers ‘do time’ (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 266; 2017; Banihani et al., Citation2013) is an issue which has been widely recognised by researchers as having a differential impact by gender, and on leadership in particular. This study found that this persists as a critical feature of career success, with those achieving chief officer ranks working the longest hours, and both male and female chief officers less likely to have worked part-time than superintendents. Working excessive hours are considered a feature of ‘masculine’ organisations, and an enduring feature of policing culture (Rabe-Hemp, Citation2008, Caless, Citation2011). Associated with work-place commitment and career success, long-hours working is considered to impact particularly negatively on women in the workplace and in policing (Banihani et al., Citation2013, Österlind and Haake, Citation2010). There is also the additional issue of part-time working; given the need to keep moving between ranks at a pace, together with evidence part-time working can limit the career advancement of women in particular (Silvestri, Citation2006), working part-time at any point in a career is not generally associated with those who ascend to the highest ranks.

The working hours reported in the survey, particularly by chief officers, match those identified in previous studies and suggest a perverse association with career success despite being likely to undermine professional judgement, family relationships and health (Caless, Citation2011). While working excessive hours is frequently associated with a ‘masculine’ culture and with operating in senior positions (Österlind and Haake, Citation2010), there was no evidence among the male superintendents interviewed of men actually wanting to work such hours, but rather they considered there to be no choice.

Having partners who work fewer hours can off-set occupational stress for male officers and provide greater access to the ‘resource of time’ (Silvestri, Citation2006, p. 274). For senior women, whose partners mostly work full-time, long hours and work pressures are considered likely to cause marital conflict (Silvestri, Citation2006), potentially contributing to the greater number of failed relationships reported by women in this survey, and their subsequent settling with new, and arguably more supportive, partners (Alexander, Citation1995).

Managing careers and families presents an enduring challenge to male and female senior officers alike, although the challenges may differ by gender. While still appearing to present greater barriers for women’s career advancement, for men the perceived absence of such barriers arguably brings other costs in terms of hours worked, impact on family life and pressure to continue striving for promotion at a pace. As observed by Collier (Citation2019, p. 81), the concept of men in the workplace being ‘somehow unaffected by demands, commitments and responsibilities of parenthood’ should be subject to more challenge. Even in Scandinavian countries where more ‘family-friendly’ working policies exist, studies reveal an enduring reality of men continuing as the main ‘bread-winners’ and of those with school-aged children working even longer hours than men without any children at all (Dommermuth, & Kitterød, Citation2009). While many studies have focussed on gendered organisations and constructs of leadership favouring the progress of men in the workplace (Braun et al., Citation2017), framing this as positive advantage, there appear to be far fewer studies which have considered how societal pressures on males to conform with gender congruity may also be limiting the choices they feel they have in the workplace. With partners more likely to work part-time, larger families, and expectations of continuing career success once they have put their feet on the first rung of the ladder, it is contended in this study that males may feel obliged to apply for promotions regardless of whether they are ready or are even genuinely desirous of them.

Conclusion and recommendations

Analysing primary data alongside secondary data raises some critical questions regarding the extent of chief officer or government commitment to gender diversity in police leadership. Home Office publications on work-force data expose a real lack of understanding or challenge regarding the differential experience of women. The Metropolitan Police Service, the largest force by far, were unable to provide promotion data by gender (Home Office, Citation2019a); and FOI responses indicate a concerning absence of force-wide, let alone national, collation or understanding of policing as a career for women, from almost any point from application to exit. Such data could, if available and shared, be used to highlight good practice. The reality is thus that, over 100 years after first having police officer status, women continue to be overlooked and undermined, unless they exhibit qualities which accord with the hegemonic masculine norms of policing.

With concerns around the small number of officers applying for the Police National Assessment Centre (PNAC) which selects future chief officers, and the limited size of the talent pool applying for these posts (College of Policing, Citation2017), the negative impact the excessive hours chief officers are seen to work has on application rates, is an issue that policing needs to consider and address as a matter of some urgency. Witnessing such long hours is likely to limit women’s applications for senior posts in particular, given that caring responsibilities are more likely to prohibit the capacity for these working hours.

Until the cultural and structural barriers identified in this study are dismantled, women are likely to continue feeling they do not belong in policing’s higher ranks to the extent men do (Veldman et al., Citation2017). Rather than just for women, however, but also for the sake of transforming public service and for the wellbeing of all police officers, this research calls for a renewed organisational and government focus on how a representative diverse police workforce is going to be recruited, retained and enjoy equal career success. The current ‘uplift’ in the numbers of new recruits into policing potentially provides a real opportunity for such a focus to be introduced and maintained; but without a commitment to sustained change and gender parity across all policing roles and ranks, which it is proposed here requires more thorough and accurate monitoring and evaluation by the Home Office and the NPCC, it is considered likely to just become yet another example of women officers’ ‘progression and regression’.

To conclude, a number of recommendations are made; the principles of these, given the global commonality of gendered policing (Garcia, Citation2021) are considered generalisable to police forces internationally and to other public and private organisations.

That the under-representation of women in the rank of sergeant is addressed, and all women constables qualified for promotion to sergeant provided with support in applying for promotion.

That all forces monitor temporary promotions by gender, and ensure that evidence of gender bias in their processes is addressed.

That Home Office data returns include force data by gender regarding officer applications, promotion and temporary promotions, so that national comparisons can be made, and good practice identified and shared.

All promotion boards should be centralised or overseen independently, e.g., by the College of Policing, to ensure that gender bias is removed.

That the Home Office workforce reports separate out the three ranks, ACC, DCC and chief constable, rather than pooling them together as ‘chief officers’.

That working hours and on-call requirements of senior officers are subject to review, and steps taken to ensure that forces are resourcing senior leadership posts adequately, with limitations on the hours that senior officers work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jackie Alexander

Jackie Alexander has moved into the world of ‘fitness to practise adjudication’ for a number of professional regulatory bodies, since retiring as a senior police officer in 2019. Her last 10 years in policing focussed on professional standards in policing, concluding with a post as the national lead for Ethics and Professional Standards with the College of Policing. Jackie’s doctorate in criminal justice (University of Portsmouth, Institute of Criminal Justice Studies) focused on police gender, culture and leadership.

Sarah Charman

Sarah Charman is a Professor of Criminology at the University of Portsmouth, UK and Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice. She has researched and published widely in the last 25 years on the sociology of policing and the policing organisation, most notably on policing cultures, police leadership, police recruits and pandemic policing. Her current research focuses on the areas of police wellbeing and police leavers.

References

- Abrams, J. R. (2012). Enforcing masculinities at the borders. Nevada Law Journal 13(1), 564–583.

- Acker, J. (1989). The problem with patriarchy. Sociology, 23(2), 235–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038589023002005

- Acker, J. (1992). From sex roles to gendered institutions. Contemporary Sociology, 21(5), 565–569. https://doi.org/10.2307/2075528

- Alexander, J. (1995). PC or not PC: that is the question: an investigation into the differential career patterns of male and female police officers in the Nottinghamshire Constabulary. MA Thesis, University of Manchester. Available from National Police Library.

- Angehrn, A., Fletcher, A. J., & Carleton, R. N. (2021, July). “Suck It Up, Buttercup”: Understanding and overcoming gender disparities in policing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147627

- Archbold, C. A., & Hassell, K. D. (2009). Paying a marriage tax: An examination of the barriers to the promotion of female police officers. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 32(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510910937111

- Banihani, M., Lewis, P., & Syed, J. (2013). Is work engagement gendered? Gender in Management, 28(7), 400–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-01-2013-0005

- Bowling, B., Reiner, R., & Sheptycki, J. (2019). The politics of the police (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/he/9780198769255.001.0001

- Braun, S., Stegmann, S., Hernandez Bark, A. S., Junker, N. M., & van Dick, R. (2017, April). Think manager—think male, think follower—think female: Gender bias in implicit followership theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(7), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12445

- British Association for Women in Policing. (2019). Forces re-commit to gender equality. Grapevine, Spring.

- Brown, J., & Bear, D. (2012). Women Police Officers May Lose Equality Gains with the Current Police Reform Programme. 2 July 2012. Retrieved from: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/police-reform-programme-bear-brown.

- Brown, J., Fleming, J., Silvestri, M., Linton, K., & Gouseti, I. (2019). Implications of police occupational culture in discriminatory experiences of senior women in police forces in England and Wales. Policing and Society, 29(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2018.1540618

- Brown, J., Gouseti, I., & Fife-Schaw, C. (2018). Sexual harassment experienced by police staff serving in England, Wales, and Scotland: A descriptive exploration of incidence, antecedents and harm. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 91(4), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X17750325

- Bury, J., Pullerits, M., Edwards, S., & DeMarco, J. (2018). Enhancing Diversity in Policing Final Report. NatCen Social Research: London.

- Cain, D. (2012). Gender within a Specialised Police Department: An Examination of the Cultural Dynamics of a Police Firearms Unit, Unpublished Professional Doctorate. University of Portsmouth.

- Caless, B. (2011). Policing at the top: The roles, values and attitudes of chief police officers. Policy Press.

- Caless, B., & Tong, S. (2015). Leading Policing in Europe: An Empirical Study of Strategic Police Leadership. Policy Press.

- Charman, S. (2017). Police socialisation, identity and culture: Becoming blue. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63070-0

- Cochran, J. K., & Bromley, M. L. (2003). The myth(?) of the police sub-culture. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 26(1), 88–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510310460314

- Cockcroft, T. (2014). Police culture and transformational leadership: Outlining the contours of a troubled relationship. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 8(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pat040

- College of Policing, (2017). Chief Officer Appointments Surveys Results and Analysis Report. Retrieved from: https://www.college.police.uk/News/College-news/Documents/Chief%20Officer%20Appointments%20surveys%20results%20and%20analysis.pdf

- Collier, R. (2019). Fatherhood, gender and the making of professional identity in large law firms: Bringing men into the frame. International Journal of Law in Context, 15(1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552318000162

- Cools, S., Markussen, S., & Strøm, M. (2017). Children and careers: How family size affects parents’ labor market outcomes in the long run. Demography, 54(5), 1773–1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0612-0

- Cross, M. (2020, March 31). Lawyers echo Sumption’s ‘police state’ warning. The Law Society Gazette. Retrieved from. https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/law/lawyers-echo-sumptions-police-state-warning/5103700.article

- Davis, C., & Silvestri, M. (2020). Critical Perspectives on Police Leadership. Policy Press.

- Dommermuth, L., & Kitterød, R. (2009). Fathers’ employment in a father-friendly welfare state: Does fatherhood affect men’s working hours? Community, Work & Family, 12(4), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800902753960

- Drew, J., & Saunders, J. (2020). Navigating the police promotion system: A comparison by gender of moving up the ranks. Police Practice & Research, 21(5), 476–490.

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

- Ergle, D. (2015). Perceived feminine vs masculine leadership qualities in corporate boardrooms. Management of Organizations: Systematic Research, 74, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.7220/MOSR.2335.8750.2015.74.3

- Garcia, V. (2021). Women in Policing Around the World: Doing Gender and Policing in a Gendered Organization (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315117607-1

- Gaston, K., & Alexander, J. (1997). Women in the police: Factors influencing managerial advancement. Women in Management Review, 12(2), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649429710162802

- Golding, B., & Savage, S. P. (2008). Leadership and Performance Management. In T. Newburn (Ed.), Handbook of policing (2nd ed., pp. 642–665). Willan.

- Haake, U. (2018). Conditions for gender equality in police leadership - making way for senior police women. Police Practice & Research, 19(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2017.1300772

- Home Office, (2018). Police Workforce, 31 March 2018. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/726401/hosb1118-police-workforce.pdf

- Home Office. 2019a. Home Office announces first wave of 20,000 police officer uplift. Retrieved from. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/home-office-announces-first-wave-of-20000-police-officer-uplift

- Home Office, (2019b). Police Workforce, 31 March. 2019. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/831726/police-workforce-mar19-hosb1119.pdf

- Home Office, (2019c). Police Workforce, England and Wales, 31 March 2019, Data Tables, second edition. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/police-workforce-england-and-wales-31-march-2019

- Johnson, R., Onwuegbuzie, A., & Turner, L. (2007). Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1, 112–133.

- Jones, M. (2015). Who Forgot Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Police Officers? Findings from a National Survey. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 9(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pau061

- Loftus, B. (2009). Police culture in a changing world. Oxford University Press.

- Maddock, S. (1999). Challenging women. gender, culture, and organization. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446217078

- Marren, C., & Bazeley, A. (2022). Sex & Power 2022. The Fawcett Society. https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=9bd9edd3-bd86-4317-81a1-32350bb72b15

- McGinley, A. C. (2013). Masculinity, labor, and sexual power. Boston University Law Review, 93(3), 795–813. Retrieved from. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=asn&AN=89713612&site=eds-live

- Metcalfe, B., & Dick, G. (2002). Is the force still with her? Gender and commitment in the police. Women in Management Review, 17(8), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420210451823

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2020). Celebrating 100 Years of Women Policing in London. Retrieved from https://www.met.police.uk/police-forces/metropolitan-police/areas/campaigns/2018/celebrating-100-years-of-women-policing-in-london/

- Mohr, T. S. (2014). Why women don’t apply for jobs unless they’re 100% qualified. Harvard Business Review Digital Articles, 2–5. Retrieved from. https://hbr.org/2014/08/why-women-dont-apply-for-jobs-unless-theyre-100-qualified

- Moutinho, L., & Evans, M. (1992). Applied marketing research. Addison Wesley.

- NPCC (2018). 2018-2025 NPCC Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Strategy. https://www.npcc.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/media/downloads/publications/publications-log/2018/npcc-diversityequality--inclusion-strategy-2018-2025.pdf

- Office for National Statistics. (2019). Sexual Orientation, UK: 2017: Experimental Statistics on Sexual Orientation in the UK in 2017 by Region, Sex, Age, Marital Status, Ethnicity and Socio-Economic Classification. Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/bulletins/sexualidentityuk/2017

- Österlind, M., & Haake, U. (2010). The leadership discourse amongst female police leaders in Sweden. Advancing Women in Leadership, 30(16), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.21423/awlj-v30.a296

- Paoline, E., & Gau, J. (2018). Police Occupational Culture: Testing the Monolithic Model. Justice Quarterly, 35(4), 670–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1335764

- Rabe-Hemp, C. (2008). Survival in an “all boys club”: Policewomen and their fight for acceptance. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 31(2), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810878712

- Reiner, R. (1991). Chief Constables: Bobbies, bosses or bureaucrats?. Oxford University.

- Rowe, M. (2006). Following the leader: Front-line narratives on police leadership. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 29(4), 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510610711646

- Saint-Michel, S. E. (2018). Leader gender stereotypes and transformational leadership: Does leader sex make the difference? Management, 21(3), 944–966. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.213.0944

- Schein, V. E. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57(2), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037128

- Silvestri, M. (2003). Women in charge: Policing, gender and leadership. Willan.

- Silvestri, M. (2006). ‘Doing time’: Becoming a police leader. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 8(4), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2006.8.4.266

- Silvestri, M. (2007). Doing’ police leadership: enter the ‘new smart macho. Policing and Society, 17(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460601124130

- Silvestri, M. (2015). Gender diversity: Two steps forward, one step back. Policing: A Journal of Policy & Practice, 9(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pau057

- Silvestri, M. (2017). Police culture and gender: Revisiting the ‘cult of masculinity. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 11(3), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paw052

- Silvestri, M. (2018). Disrupting the ‘heroic’ male within policing: A case of direct entry. Feminist Criminology, 13(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085118763737

- Stemple, C., Rigotti, T., & Mohr, G. (2015). Think transformational leadership – Think female? Leadership, 11(3), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715015590468

- Swan, A. A. (2016). Masculine, feminine, or androgynous: The influence of gender identity on job satisfaction among female police officers. Women and Criminal Justice, 26(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2015.1067175

- Taub, A. (2020, August 20). Why are women-led nations doing better with covid-19? The New York Times. Retrieved from. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/world/coronavirus-women-leaders.html

- Turnbull, P. J., & Wass, V. (2015). Normalizing extreme work in the Police Service? Austerity and the inspecting ranks. Organization, 22(4), 512–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572513

- Veldman, J., Meeussen, L., Van Laar, C., & Phalet, K. (2017). Women (do not) belong here: gender-work identity conflict among female police. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Retrieved from. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00130/full https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00130

- Ward, A., & Prenzler, T. (2016). Good Practice Case Studies in the Advancement of Women in Policing. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 18(4), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355716666847

- Woolnough, H., & Redshaw, J. (2016). The career decisions of professional women with dependent children: What’s changed? Gender in Management: An International Journal, 31(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-03-2016-0038

Appendix A:

Summary of themes addressed in senior officer survey

Current rank, gender, ethnicity, sexual identity?

Current length of service, and length of service in each rank?

Motivations to join policing?

Postings held during service and at which rank?

Had applications been made/been successful for fast-track promotion?

Any intentions to apply for promotion to the next rank, and when?

Experiences of being encouraged to apply for the next rank and who by (Command team member; a coach or mentor; other colleagues; a partner/significant other)?

Average number of hours worked per week?

Marital status? Marital status on joining police?

Partner’s attitude to them becoming/being a police officer? Was current partner a serving or former police officer?

Partner’s current employment status (not working; working part-time; working full-time; retired; other)?

Are they with same partner as when joined police?

Had a significant relationship ended while serving as a police officer/did they consider police work had contributed to relationship ending?

Former partner’s attitude to them being a police officer? Was former partner a serving or former police officer?

Do they have children/how many? Who takes primary responsibility for making child-care arrangements?

Have part-time hours been worked at any point in career (for child care; other caring responsibilities; other reason)? Has any shared parental leave been taken?

Perceptions of impact of children on rank achieved; time taken to achieve rank/have children being a motivating factor in applying for promotion?

Perceptions of whether put family before career; whether work interferes with family time; whether work and family has been successfully balanced.

Adjectives that they most associate with themselves: approachable, decisive, collaborative, innovative, assertive, committed, considerate, ambitious, passionate, strong?

Appendix B:

Senior officers semi-structured interview schedule

What motivated to you join policing?

How old were you and what was your personal situation?

Describe your career journey?

What do you feel are the main qualities you have brought to policing?

Do you feel your gender has impacted on your experiences?

What have been the high points/low points of your police career?

Why did you/didn’t you go for promotion?

Has there been a personal cost? (impact on relationships/family/number of children/impact on career)

Has your personal life limited your opportunities or advancement?

What do you think have been the key enablers or barriers to your career progression?

What career advice would you give anyone entering policing?

What qualities do you mostly see in those who make senior positions in policing (Supt. and above)?

Do these match the qualities you want to see in police leaders?

Have you ever thought about leaving policing? Why/why not?