ABSTRACT

In recent years, the psychological impact associated with ‘being a police officer’ has been brought into sharp focus. However, little has been reported on absences due to psychological illness, specifically in functions more frequently exposed to Potentially Traumatic Events (PTEs). This paper presents data collected from 23 territorial Forces in England and Wales covering 2019–2023 on ‘Frontline’ and ‘Response’ officer absence(s) attributed to psychological illness(es). The findings show overall rates of increase in the mean (40%), minimum (450%), and maximum (46%) rates of officer absence owing to psychological illnesses – at least double that of sickness absences. This paper also reports on Occupational Health Referrals (OHR) with one Force reporting a 247% rate of increase in referrals for ‘Response’ officers due to psychological illness. The paper concludes by emphasising the urgent need for attention and exploration into the causes of increased psychological illness before officer absences become unsustainable.

Introduction

Fulfilment of the policing function necessitates witnessing the most devastating of human behaviour. It is estimated that police officers are exposed to three traumatic incidents every six months (Hartley et al., Citation2013). Comparatively, non-policing civilians may be exposed to one traumatic event over the life course (Kessler et al., Citation1995). In a study by Brewin et al. (Citation2020), which looked at the prevalence of work-related exposures and traumatic incidents in policing, of 9,929 officers that reported trauma-component symptoms, 8.0% were diagnosed with PTSD, a further 12.6% were diagnosed with C-PTSD. Total rates were believed to be five times higher than the UK population.

The Blue Light Scoping Survey (MIND, Citation2015) documented that Emergency Service workers were significantly more likely to report poor mental health, with 91% of police personnel experiencing stress ,Footnote1 low mood, and/or poor mental health. Of officers surveyed, 61% reported mental health problems; the highest figure recorded amongst all emergency services personnel. In a Labour Call for Review, it was reported that suicide rates amongst police officers have risen by a third since 2009 (Townsend & Savage, Citation2019). Concurrently, the National Police Wellbeing Survey 2023 reported that work-related impact factors including ‘Stressors’ ,Footnote2 were rated ‘high’ by officers (Graham et al., Citation2023), and 2023 also saw the highest number of officer resignations since records began (Police Federation, Citation2024), echoing narratives citing inadequate head counts, poor resource management, and unplanned absences as contributing to demand (Elliott-Davies et al., Citation2016).

Despite this reality, few papers have explored explicit links between psychological state of officers and the measurable impact(s) on Forces. Cartwright and Roach (Citation2020) sought to redress this gap by reporting on absences over a 10-year period, up to 2019. They found that absences due to poor psychological health had almost doubled since the start of the decade, and that absences due to psychological ill-health were at an all time high. Since then, papers mapping continuing trends have been sparse. As focus turns to precision within policing (Lin & Rejniak, Citation2018), alongside continuing disproportionality between resourcing and demand (House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, Citation2018), there is significant benefit to highlighting anticipatory ‘pinch points’ where there requires a need for urgent attention. Further, with the establishment of the National Policing Wellbeing Service in 2019, and the launch of the Police Uplift ProgrammeFootnote3 to address demand, an update is surely due. The aim of this paper is to provide an updated report on the absences of ‘Frontline’ and ‘Response’ officers owing to psychological illness – functionsFootnote4 of interest due to the potential for more frequent exposure to PTEsFootnote5 in accordance with DSM-5 categories, where police officers are specifically cited (ibid).

Method

To ascertain whether more ‘Frontline’ and ‘Response’ officers are increasingly absent resultant of psychological illness, data was collected from ForcesFootnote6 in England and Wales on the number of sworn-in officers within the function(s) that had taken an absence owing to psychological illnessFootnote7 over the period September 2019–September 2023. The data focuses on number of officers that took an absence, as opposed to number of absences. This is to insulate against concentrations of officers with high rates of multiple absences that would otherwise affect the validity of findings.

Data was collected using FoI requests which were deemed the most suitable method owing to the benefits of official recording, legislated return deadlines, and high confidence in accuracy of data owing to the accountability held by the Information Commissioner’s Office. FoI requests are common within research of policing agencies (Hester & Hobson, Citation2023), and precedent to use the method within police wellbeing research has been well-established (Cartwright & Roach, Citation2020).

Requests were sent to the 43 territorial Forces of England and Wales. The initial focus was to explore ‘Response’ officers absences; however, due to constraints in categorisation, some Forces were unable to separate ‘Response’ officers from the wider ‘Frontline’ function. Therefore, data was collected for either ‘Response’ or ‘Frontline’, based on Force categorisation, where ‘Response’ exists as a sub-function within ‘Frontline’.

The following data was requested:

As at September of each year, the total number of ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers within Force

Total number of ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers that took any period(s) of sickness absence within each period (Sept 2019–Aug 2020, Sept 2020–Aug 2021, continued…)

Total number of ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers that took any period(s) of sickness absence within each period (as above) resultant of psychological illness: mental ill-health, trauma exposure, stress and stress-related conditions, or psychological injury

Number of ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers who, between Sept 2019 and Sept 2023, took multiple period of absence due to psychological illness (categories as above).

Further to this, Forces were also asked to provide Occupational Health referrals (OHR) data in response to the following:

Total number of OHR made for ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers within each period (as above) for concerns relating to psychological illness (categories as above)

Total number of officers (not limited to ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’) with an OHR within each period (as above) for concerns relating to psychological illness (categories as above).

A compliance rate of 53% was observed with 23 Forces providing useable data. An additional seven Forces responded, but were unable to provide data. Of Forces that were unable to provide a complete return, the most cited reasons for non-compliance were: data not held in an easily retrievable format; officers not separable by function; data not separable into periods requested. Pertaining to Q5 and Q6 (OHR), six of the 23 Forces compliant in the return were able to provide data in response to these questions. The most cited reason for non-compliance was due to time constraints where OHR’s required manual collation and would exceed the maximum time allowance permitted in accordance with S12 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

Forces provided five figures in response to Q1 reflective of total ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers as at Sept of each year (2019, 2020 … 2023). To account for fluctuating staffing levels, the mean was calculated from the number at September of each year to produce an average that represented each of the four yearly absence periods. This number ensured that any identified trends were proportionally representative. In response to Q2 and Q3, Forces provided four figures, for each question respectively, which represented number of officers with one or more absence reported within each of the yearly periods concerned (2019–2020…2022–2023). In response to Q4, Forces returned a single number representing number of officers that had taken multiple periods of absence due to psychological illness(es) over the 5-year period. These numbers were then used to create percentage reports presented below.

NB: To ensure focus is held on the critical importance of the absences themselves, Force identities have been redacted and listed as F01-F23 based on order of return. To indicate which function was returned, ‘Response’ is represented by (R) and ‘Frontline’ by (F). For additional context, Forces have been categorised into terciles represented as large (L), medium (M), or small (S) based on number of sworn-in officers per 100,000 people by Force area, as at 2023 (Allen & Carthew, Citation2024).

Findings

As displayed in , twenty-one Forces reported increases in officer absence due to sickness, excluding psychological illness, between 2019 and 2023. Downward trends were present in 18 Forces between −22 and −23. Summary statistics show an increase in mean absences at a rate of increase of 20%. This is accompanied by a rise in the minimum absence rate at a rate of increase of 229%, and a decrease at a rate of 10% in maximum absences.

Table 1. Reports officers who took an absence due to sickness, excluding psychological illness, as a percentage of officers within the function (Q2), including summary statistics and year-year changes in mean expressed as rate of increase/decrease.

As displayed in , overall increases were reported in 20 of 23 Forces. Of those, F04, F05, F08, F09, F13, and F17 show consistent increases, and reductions occurred in 10 Forces in 20–21. The final column denotes number of officers, of all officers within the function, who have taken multiple periods of absence over the 5-year period attributed to psychological illness, the mean number of which is 10.2%. All summary statistics show consistent increases. Mean absences have increased at a rate of 40%, which is accompanied by increases in both the minimum and maximum absences at a rate of increase of 450% and 46%, respectively. Running a t-test on the difference between 2019–2023 mean produced a p-value of 0.0002.

Table 2. Reports officers who took an absence due to psychological illness as a percentage of officers within the function (Q3), including summary statistics and year-year changes in mean expressed as rate of increase/decrease.

As displayed in , data has been supplied limitedly, however, OHR figures trend upwards, particularly between 2021 – 2023. The most significant reduction is seen in F03, which has also returned reductions in absences owing to psychological illness.

Table 3. Percentage of OHR for ‘Frontline’ or ‘Response’ officers attributed to psychological illness as a percentage of OHR across all officers within the Force.

Discussion

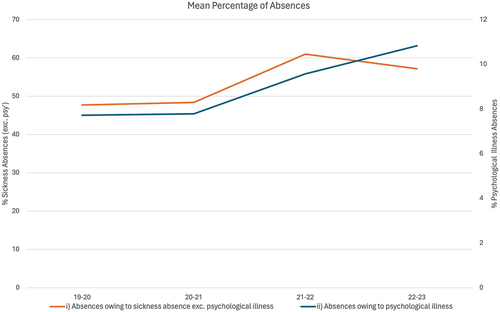

Analysis of the data reveals several noteworthy trends. Firstly, the mean officer absence rate owing to psychological illness has risen by over 40% – more than double the rate of increase of sickness absences (). This is accompanied by an increase in the minimum absence rate, rising by 450% – more than three times that of sickness absences. The maximum absence rate has also seen an increase of 46%, whereas the rate of sickness absences, excluding psychological illness, has decreased by 10%.

Figure 1. Displays the mean percentage of officers that have taken an absence owing to: (i) sickness, excluding psychological illness; (ii) psychological illness.

Importantly, 10 Forces reported reductions in psychological absences over 20–21. This could be explained by positing that higher rates of absenteeism, legally mandated resultant of Covid-19, produced occurrences whereby officers who might have otherwise taken leave due to psychological illness were experiencing contemporaneous absence in the form of isolation(s), reducing the need to report psychological illness. The same pattern of absences attributed to poor mental health were reported across other professional industries reasoned as owing to a number of isolation benefits (Wishart, Citation2022). Inducement for not citing psychological illness is supported by recent studies which have reported that stigma associated with poor mental health remains prevalent within policing (Bell et al., Citation2022). Consequently, arguments that the figures do not reflect an increase in psychological illness(es), but instead reflect a change in culture that empowers officers to cite psychological illness, are likely to prove inconclusive. Instead, the reported absenteeism is likely to significantly underrepresent the ‘true’ crisis being experienced by officers noting that absenteeism is not the only indicator associated with psychological illness, i.e., suicidal ideation, alcohol dependency, and other psychophysiological conditions are associated in kind (Syed et al., Citation2020).

Whilst overall increases are observed, there exists noticeable heterogeneity between Forces highlighting the complexities of the relationship between officers and their Forces. Force 03 reports the most significant decrease in officers taking absence due to psychological illness, as well as the only reported decrease in OHR. There could be many reasons to explain this, but one notable consideration is that Force 03 is known to have invested significantly in the prioritisation of mental health support and intervention within the Force.Footnote8 This postulation is supported by literature that advises that the develop of trauma-related symptoms can be stalled with early intervention (Freedman et al., Citation2015; O’Donnell et al., Citation2020; Rothbaum et al., Citation2012). Further research might examine differences in workplace culture, and knowledge of available support across career stages, both across Forces and over time to account for shifting compositions of Forces. Although some of this information was collected within the MIND Blue Light Survey, it was not recorded by-Force, nor over the period concerned.

Reflecting on the overarching trends of absences attributed to psychological illness, it is clear that one of two possibilities exist: either, officers are increasingly afflicted by psychological illness; or, officers are increasingly attributing their absences to psychological illness. Without further research, it is not possible to determine causation, however, in either case, the figures paint a concerning picture of the psychological state of officers within ‘Frontline’ and ‘Response’ functions, and ought to act as the basis for Forces to consider this a critical priority.

Limitations

Firstly, the data may not be reflective of all Forces; however, those included herein are demographically representative of all Forces in England and Wales. This has been validated by comparing officer demographics Forces herein with the national sample (Home Office, Citation2020-, 2020–2024) where no notable deviations were found. Secondly, it is noted that data covering March 2020–February 2022 may present concerns of reliability as the period covering COVID-19 peaks in England and Wales. However, it is known that COVID-19 and mandatory isolations were recorded separately by Forces with categories such as ‘unavailable for work’ and ‘working from home – isolation’, being applied (Bland, Citation2023). Separately, recorded absences due to COVID-19 isolations were presented in Bland (Citation2023) covering April 2020 - October 2021. Accordingly, the FoI returns were compared to isolation figures to identify potential cross-contamination. It was determined that if the returns inadvertently included COVID-19 isolations, a discernible spike would be present in absences over 2020–2021. Instead, 15 of 23 Forces reported the greatest number of sickness absences between September 2021–2022, which aligns with the withdrawal of mandatory isolations and separate COVID-19 absence reporting as of February 2022.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Matthew Bland of the Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge, and Professor Jeffrey Dalley of the Department of Psychology, University of Cambridge, for their continued supervision and support, and give thanks to colleague, Nicholas Goldrosen, for providing additional comments on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emily Quin

Emily Quin is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Cambridge where she specialises in the phenomenological experiences of first responders (operational police officers), and the associated biopsychological mechanisms and adaptations using large-scale primary data. She is also a 2024 CDH Methods Fellows, and holds GBC status with the British Psychological Society.

Notes

1. Presumed ‘chronic’.

2. Including both ‘Challenge Stressors’ and ‘Hindrance Stressors’.

3. PUP was introduced by the UK Government to address key public safety priorities by recruiting 20,000 additional officers by March 2023.

4. In England and Wales, ‘Response’ is a uniformed function responsible for responding to incidents (‘999’ calls), and exists as a sub-function of ‘Frontline’. ‘Frontline’ varies by Force, but typically includes all public-facing roles, such as ‘Custody’, ‘Neighbourhood Patrol’, and ‘Traffic’ functions.

5. ‘e.g. exposure to threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence’ (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

6. ‘Forces’ used in lieu of ‘Constabulary’, ‘Service’, ‘Agency’.

7. Classified within the ‘Mental Health’ absence categories of each Force.

8. Based on College of Policing data not here shared to otherwise identify the Force.

References

- Allen, G., & Carthew, H. (2024). Police service strength (house of commons briefing ( Paper SN00634). https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn00634.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association,

- Bell, S., Palmer-Conn, S., & Kealey, N. (2022). ‘Swinging the lead and working the head’ – an explanation as to why mental illness stigma is prevalent in policing. The Police Journal, 95(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258x211049009

- Bland, M. (2023). Excess mortality, sickness and absence in the police workforce in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 17. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paad017

- Brewin, C., Miller, J., Soffia, M., Peart, A., & Burchell, B. (2020). Posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in UK police officers. Psychological Medicine, 52(7), 1287–1295. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720003025

- Cartwright, A., & Roach, J. (2020). The wellbeing of UK police: A study of recorded absences from work of UK police employees due to psychological illness and stress using freedom of information act data. OUP Academic. https://academic.oup.com/policing/article/15/2/1326/5864637

- Elliott-Davies, M., Donnelly, J., Boag-Munroe, F., & Van Mechelen, D. (2016). ‘‘Getting a battering’.’ The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 89(2), 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258x16642234

- Freedman, S., Dayan, E., Kimelman, Y., Weissman, H., & Eitan, R. (2015). Early intervention for preventing posttraumatic stress disorder: An Internet-based virtual reality treatment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.25608

- Graham, L., Plater, M., & Brown, N. (2023, November). National police wellbeing survey: summary of evidence and insights. https://www.oscarkilo.org.uk/news/national-police-wellbeing-survey-2023-results

- Hartley, T., Violanti, J., Sarkisian, K., Andrew, M., & Burchfiel, C. (2013). PTSD symptoms among police officers: Associations with frequency, recency, and types of traumatic events. PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24707587

- Hester, R., & Hobson, J. (2023). The true cost of policing football in England & Wales: Freedom of information data from 2015–2019. Police Practice & Research, 24(4), 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2022.2130310

- Home Office. (2020-2024). Collection: Police officer uplift statistics. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/police-officer-uplift-statistics

- House of Commons Home Affairs Committee. (2018). Policing for the future. House of Commons, HC, 515, 25.

- Kessler, R., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

- Lin, T., & Rejniak, M. (2018). 10. NYPD ShotSpotter: The policy shift to “precision-based” policing. In Columbia University Press eBooks (pp. 253–276). https://doi.org/10.7312/dalm18374-014

- MIND. (2015). Blue light scoping survey police summary. https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/4583/blue-light-scoping-surveypolice.pdf

- O’Donnell, M., Pacella, B., Bryant, R., Olff, M., Forbes, D. (2020). Early intervention for trauma-related psychopathology. In D. Forbes & J. I. Bison (Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies (pp. 117–131). Guildford Press.

- Police Federation. (2024, January 11). Challenges faced by police demand urgent attention and reform. https://www.polfed.org/news/latest-news/2024/challenges-faced-by-police-demand-urgent-attention-and-reform/

- Rothbaum, B., Kearns, M., Price, M., Malcoun, E., Davis, M., Ressler, K., Lang, D., & Houry, D. (2012). Early intervention may prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized Pilot civilian study with modified prolonged exposure. Biological Psychiatry, 72(11), 957–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.002

- Syed, S., Ashwick, R., Schlosser, M., Jones, R., Rowe, S., & Billings, J. (2020). Global prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in police personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational & Environmental Medicine. https://oem.bmj.com/content/77/11/737

- Townsend, M., & Savage, M. (2019). Labour calls for review into police welfare as suicide figures revealed. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/aug/10/labour-calls-for-review-into-police-welfare-as-suicide-figures-revealed

- Wishart, M., (2022). Workplace mental health and well-being during COVID-19: Evidence from three waves of employer surveys. ERC Insight Paper, Enterprise Research Centre.