Abstract

Objectives: Partial or non-adherence in patients with schizophrenia is common and increases the risk of relapse. This study explored safety, tolerability and treatment outcomes in patients hospitalised for an exacerbation of schizophrenia initiated on maintenance treatment of once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M).

Methods: A 6-week, observational cohort study of patients initiated on PP1M within 3 weeks after hospital admission.

Results: Overall, 367 patients were documented, 85.8% with paranoid schizophrenia subtype. Mean time from hospital admission to PP1M initiation was 9.4 ± 7.7 days. Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported by 22.9% of patients. From baseline to endpoint, significant improvements were observed in psychotic symptoms (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale total score mean change –19.3 ± 12.6, P < .0001) and functioning (Personal and Social Performance scale total score mean change 14.3 ± 12.4, P < .0001). Overall, 6.0% of patients were very or extremely satisfied with their prior antipsychotic medication at baseline compared with 47.2% very or extremely satisfied with PP1M treatment at endpoint.

Conclusions: Initiating PP1M in patients with exacerbated schizophrenia shortly after hospital admission was well tolerated and resulted in statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements in symptoms and patient functioning, suggesting that patients may benefit from early initiation of PP1M during their hospital stay.

Introduction

Relapse rates after hospitalisation for schizophrenia are high, with more than half of patients discontinuing their antipsychotic medication within 1 month after discharge (Tiihonen et al. Citation2011) and a similar proportion relapsing in the first year after discharge (Schennach et al. Citation2012). Both partial adherence and non-adherence to oral antipsychotic medication are challenging aspects of schizophrenia treatment, and are associated with increased risk of relapse, rehospitalisation and suicide (Ascher-Svanum et al. Citation2010; Novick et al. Citation2010; Higashi et al. Citation2013). Non-adherence to oral antipsychotic medication has been shown to result in an almost five-fold increase in the risk of relapse (Robinson et al. Citation1999).

Although oral antipsychotics are recommended for the treatment of acute schizophrenia (National Institute for Health & Care Excellence Citation2014), more than half of patients with schizophrenia (54%) do not collect their prescription within 1 month after hospital discharge (Tiihonen et al. Citation2011). In addition, patients with a recent hospitalisation (within 6 months) are 22% less likely to adhere to treatment (Novick et al. Citation2010). Long-acting injectable antipsychotic therapies (LATs) help to overcome the problems of partial adherence and non-adherence (Brissos et al. Citation2014) and may improve outcomes for patients. Indeed, naturalistic studies have shown that patients treated with LATs have a significantly longer time to discontinuation (Bitter et al. Citation2013) and reduced rates of hospitalisation (Kishimoto et al. Citation2013) compared with those treated with oral antipsychotics. A meta-analysis of mirror-image studies comparing LATs with oral antipsychotics found that patients receiving LATs had a 57% reduced risk of rehospitalisation and a 62% lower number of hospitalisations compared with those receiving oral antipsychotics (both P < .001) (Kishimoto et al. Citation2013). Similarly, a US-based study found that, 1 year after initiation of LAT, the number of all-cause hospitalisations and number of hospital days were significantly lower compared with the period before initiation of LAT (P < .0001), regardless of patient age (Kamat et al. Citation2015). Guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia indicate that, in patients with one or more relapses due to partial or non-adherence, the transition from oral antipsychotics to long-term treatment with LATs may already be initiated in the acute phase (American Psychiatric Association Citation2010), and should be considered at any stage of the disease, including the earlier stages (Malla et al. Citation2013).

The recommended initiation regimen for paliperidone palmitate (PP1M), an atypical once-monthly LAT, is two injections (150 mg eq. on Day 1 and 100 mg eq. on Day 8), allowing for a rapid attainment of therapeutic plasma concentrations (Janssen Cilag et al. Citation2016). Long-term maintenance treatment with PP1M may be initiated early within a hospital setting in symptomatic patients with previous responsiveness to oral paliperidone extended release (ER) or risperidone if psychotic symptoms are mild to moderate and a long-acting injectable treatment is needed. The objective of this study was to explore treatment outcomes, appropriate use, and safety and tolerability in patients hospitalised for an exacerbation of schizophrenia where maintenance treatment with once-monthly PP1M was initiated at the discretion of the treating physician within the first 3 weeks after the patient’s admission to hospital.

Methods

Study design

This was an international, 6-week, prospective, observational, non-interventional, non-comparative cohort study conducted at 61 sites in nine countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan and Russia). Owing to the non-interventional nature of this study, patients were eligible to participate only if all treatment decisions were made at the discretion of the treating physician before the start of the study, and study participation in no way impacted on the regular care of the patient, or on any benefits to which they were otherwise entitled. Study duration was limited to 6 weeks to capture a reasonable timeframe for a hospital stay and to have the first three injections documented. Data were only collected in patients who, in the opinion of the treating physician, were capable of providing consent. Written informed consent was obtained prior to any study documentation. Applicable regulatory requirements and the study protocol were approved by Independent Ethics Committees in each country. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01926912).

Key selection criteria

Adult (≥18 years) patients with an established schizophrenia diagnosis who were admitted to hospital due to an exacerbation of their disease prior to any study activity and who, in the investigator’s opinion, could benefit from long-term maintenance treatment with PP1M, were initiated within the first 3 weeks after admission to hospital. The decision to initiate treatment with PP1M must have been made prior to offering enrolment and in accordance with routine clinical practice. Patients were not eligible for documentation in this study if they had previous exposure to PP1M; exposure to any other LAT and/or to clozapine within the previous 3 months; or were involuntarily hospitalised at study entry (i.e. at the beginning of data collection).

Study objectives

The primary objective of the study was to assess treatment response, tolerability and appropriate use of PP1M initiation in clinical practice in symptomatic patients with schizophrenia admitted to hospital due to an exacerbation of the disease.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included change from baseline in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall & Gorham Citation1962), Clinical Global Impression – Severity (CGI–S) score, Clinical Global Impression – Change (CGI–C) score (Guy Citation1976), Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale score (Morosini et al. Citation2000; Nasrallah Citation2008) and treatment response.

Treatment response

Treatment response was assessed through psychiatric symptoms and disease severity, as measured by actual values and changes from baseline in BPRS (Overall & Gorham Citation1962), CGI–S and CGI–C (Guy Citation1976) scores. Patient functioning was assessed using the PSP scale (Morosini et al. Citation2000; Nasrallah Citation2008). Patient’s treatment satisfaction was assessed via the Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) (Vernon et al. Citation2010), completed at baseline (for previous antipsychotic medication[s]) and endpoint (for PP1M).

Clinically relevant improvement

A 20% and 50% reduction from baseline BPRS scores indicates ‘minimally clinically improved’ and ‘much clinically improved’, respectively (Leucht et al. Citation2005). The CGI–C rating scale compares the change in clinical status of a patient since the start of treatment (1 = very much improved since the initiation of treatment; 2 = much improved; 3 = minimally improved; 4 = no change; 5 = minimally worse; 6 = much worse; and 7 = very much worse). Finally, a 10-point increment in PSP has been reported as a clinically meaningful improvement (Nicholl et al. Citation2010).

Assessment scales

The BPRS is a validated scale, specific for the measurement of psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia, and comprises the following 18 symptom items: Somatic concern; Anxiety; Emotional withdrawal; Conceptual disorganisation; Guilt feelings; Tension; Mannerisms and posturing; Grandiosity; Depressive mood; Hostility; Suspiciousness; Hallucinatory behaviour; Motor retardation; Uncooperativeness; Unusual thought content; Blunted affect; Excitement; and Disorientation. Each item is scored on a scale of 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe). The total BPRS score is calculated as the sum of the scores from the 18 items. The BPRS was assessed at those sites where this scale is used as part of routine clinical practice.

The CGI–S rating scale is used to rate the severity of a patient’s psychotic condition at a particular time on a seven-point scale (0 = normal, not at all ill; 1 = borderline mentally ill; 2 = mildly ill; 3 = moderately ill; 4 = markedly ill; 5 = severely ill; and 6 = among the most extremely ill patients) and allows a global evaluation of the patient’s condition at a given time.

The PSP scale assesses the degree of dysfunctionality that a patient exhibits over the 1-week period prior to the visit within four domains of behaviour: (a) socially useful activities; (b) personal and social relationships; (c) self-care; and (d) disturbing and aggressive behaviour. The score for each domain rates the difficulty within that domain, with scores ranging from 1 (absent) to 6 (very severe). The results of the assessment are converted to a total score ranging from 1 to 100, with higher scores representing better functioning. A score of 71 to 100 indicates mild to no impairment; 31 to 70 indicates varying degrees of disability ranging from severe (31–40) to manifest but not marked (61–70); and a score ≤30 indicates functioning so poor that the patient requires intensive supervision.

Safety and tolerability

Safety assessments included monitoring of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), body weight and extrapyramidal motor symptoms (EPMS), as measured by the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) (Chouinard & Margolese Citation2005).

Data analysis

Baseline data were collected at the initiation of PP1M (Day 1). During the observation period, data were collected weekly until Week 6 (Day 43 ± 7 days) or at early study discontinuation. Data for BPRS and CGI–S were collected at all visits during the study. Data for CGI–C and PSP were collected at Day 43 and endpoint only. The MSQ was assessed at baseline (for previous antipsychotic medication[s]) and endpoint (for PP1M).

All documented patients who provided written consent and who received at least one dose of PP1M (documented population) were included in the statistical analyses. Analysis of treatment response was conducted using the efficacy analysis set, comprising all patients in the documented population who provided at least one post-baseline treatment-response assessment. Safety analyses were conducted using the safety analysis set, defined as all patients in the documented population who received at least one dose of PP1M and provided any post-baseline safety information. In this study, the safety population is identical to the documented population.

The study was designed to generate naturalistic data on treatment response, tolerability and appropriate use of PP1M initiation in a hospital setting. The target sample size was selected to allow collection of data on a representative sample of symptomatic patients with schizophrenia who were admitted to hospital due to exacerbation of their disease and to allow for potential exploratory analyses in various patient subgroups. A sample size of approximately 100 patients was considered reasonable for any potential subgroup to enable detection of small incidence rates (i.e. incidence rates of specific AEs or discontinuation rate due to AEs with an expected incidence rate of 5–15% in an expected proportion of 5%, and a corresponding distance of 4% from the observed incidence rates for a one-sided 95% confidence interval. The target sample size of 450 patients was selected to collect data on a sample of symptomatic subjects with schizophrenia, admitted to hospital due to an exacerbation of their disease and allow for potential subgroup analyses, three to four subgroups of 96 patients each. The total number of patients that were documented and received at least one dose of PP1M was 367, which was large enough for the overall analysis and did not impact the final results. In addition, the main subgroup of interest (‘acute subjects’) that was analysed and reported contained more than 96 subjects, thereby meeting the target sample size. For continuous variables and those measured at ordinal level, all values presented are mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified, and changes from baseline were tested using the Wilcoxon-signed rank test. All statistical tests were interpreted at the 5% significance level (two-tailed), unless otherwise specified. Kaplan–Meier survival curve estimates were used to analyse time from admission and time from first PP1M injection until discharge. Frequency distributions are reported for categorical variables. The last observation carried forward (at Week 6 or early discontinuation) method was used for endpoint analysis. All reported AEs with onset during the observational period and/or AEs that worsened from baseline (i.e. TEAEs), were included in the AE analysis. Any AEs reported by patients or their caregivers, as well as those assessed during study visits, were recorded and monitored by the treating physician. All AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA® version 15.1) (International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations Citation2012). For all reported TEAEs, frequency distributions included severity of the events (mild, moderate, severe), causal relationship to treatment (not related, doubtful, possible, probable, very likely), action taken and outcome.

Results

Demographics and patient disposition

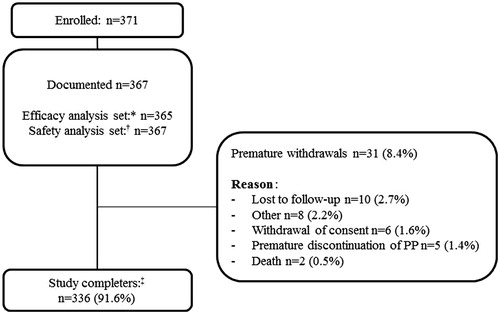

Patient disposition is described in . In total, 371 patients were enrolled, of whom 367 received at least one dose of PP1M and were included in the documented population. Overall, 91.6% of patients completed the 6-week observation period.

Figure 1. Patient disposition. ‘Documented’ refers to all patients who provided written consent and received at least one dose of PP1M. *Efficacy analysis set consisted of all patients who received at least one dose of PP1M and had at least one post-baseline efficacy assessment. †Safety analysis set consisted of all patients who received at least one dose of PP1M and had at least one post-baseline safety assessment. ‡Patients who completed all study documentation up until Week 6. PP1M: paliperidone palmitate.

Baseline characteristics are summarised in . Most patients were male (65.9%); mean age 39.8 ± 12.1 years. The most frequently diagnosed subtype was paranoid schizophrenia (85.8%). Most (91.3%) patients had at least one previous psychiatric hospitalisation; mean time from schizophrenia diagnosis to start of documentation in the study was 11.4 ± 10.5 years.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and dosing information (documented population; n = 367).

The vast majority of patients (96.5%; n = 354) received treatment with at least one oral antipsychotic in the 4 weeks prior to the first PP1M injection; 68.7% received oral atypical antipsychotics, the most common of which were paliperidone ER (29.4%) and risperidone (24.8%), whereas conventional oral antipsychotics were used in 59.1% of patients, the most common of which were haloperidol (37.9%) and chlorpromazine (15.3%). The main reasons for initiating treatment with PP1M included partial or non-adherence to previous treatment (40.1%); lack of efficacy with previous treatment (37.9%); convenience of LAT medication regimen (11.2%); lack of tolerability with previous treatment (9.5%); and patient’s wish (1.1%). Mean time from hospital admission to PP1M initiation was 9.4 ± 7.7 days (range 0–63). Most patients (88.8%) received the PP1M initiation regimen according to the approved label. Overall, 89.6% (n = 329) of patients received a third injection of PP1M within the study period.

Safety and tolerability

Overall, in the safety population, 22.9% (84/367) of patients reported ≥1 TEAE, and a causally, i.e. at least possibly, related TEAE was reported in 11.4% (n = 42) of patients. Most TEAEs (93.4%, 142/152) were mild or moderate in intensity. One or more serious TEAEs were reported in 3.5% (n = 13) of patients. Four patients experienced a TEAE leading to treatment discontinuation. Two patients were discontinued due to a TEAE with fatal outcome (viral pneumonia (n = 1) and loss of consciousness (n = 1)). Both deaths were considered not to be related to PP1M treatment by the treating physicians. Two patients discontinued due to akathisia (n = 1) and extrapyramidal disorder (n = 1). TEAEs reported in ≥2% of patients included tremor (n = 9, 2.5%) and schizophrenia (n = 8, 2.2%). Overall, 54.6% (83/152) of TEAEs resulted in initiation of concomitant medication. The majority of TEAEs (75.7%) were resolved at the end of the study. One female patient reported a potentially prolactin-related TEAE (galactorrhoea). No blood measurements for prolactin were required as part of this non-interventional study. The mean change in body weight from baseline (76.4 ± 15.5 kg) to endpoint (77.4 ± 15.5 kg) was 1.0 ± 3.1 kg, and the mean change in body mass index from baseline (26.0 ± 4.8 kg/m2) to endpoint (26.3 ± 4.8 kg/m2) was 0.3 ± 1.0 kg/m2. At endpoint, 9.7% of patients had a ≥7% increase in body weight. The most common EPMS were tremor, occurring in nine patients (2.5%), and akathisia, occurring in seven patients (1.9%). Mean ESRS total score (scale range 0–102) at baseline was 3.7 ± 5.9. There was a statistically significant reduction, i.e. improvement, in ESRS total score at all time points throughout the study (all P values < .0001), with a score of 3.0 ± 5.3 (mean change −0.7 ± 2.5) at Day 8 and 2.0 ± 4.7 at endpoint (mean change –1.7 ± 4.8).

Treatment response

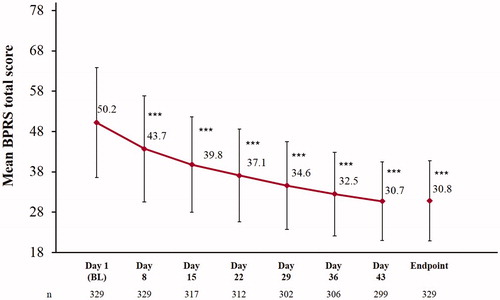

In the efficacy analysis population, at endpoint, 86.0% and 69.6% of patients had achieved a ≥30% and ≥50% improvement in BPRS total score, respectively. In this population, mean BPRS total score decreased from baseline (50.2 ± 13.6) to endpoint (30.8 ± 9.9), reflecting a statistically significant and clinically relevant symptom improvement (mean change −19.3 ± 12.6, P < .0001; ). Statistically significant improvements in BPRS total score were observed as early as Day 8 (the earliest post-baseline time point when treatment response was measured), with a mean change from baseline to Day 8 of −6.5 ± 8.6, P < .0001.

Figure 2. Change in mean BPRS total score over time (efficacy analysis set; n = 365). Statistically significant improvements in BPRS total score were observed at each timepoint after baseline, starting as early as Day 8. ***Mean change P < .0001 vs BL, Wilcoxon-signed rank test. BPRS total score calculated as sum of 18 single-item scores on a scale of 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe), ranging from 18 to 126. Scores of BPRS, both at baseline and post-baseline, were available for 329 patients within the efficacy analysis set. Error bars represent SD. BL: baseline; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Statistically significant improvements were also observed in disease severity from Day 8 onwards (change from baseline −0.3 ± 0.7, P < .0001). Mean CGI–S score at endpoint was 2.3 ± 1.1 (change from baseline −1.4 ± 1.1, P < .0001). The proportion of patients categorised in CGI–S as ‘markedly ill’ (CGI–S score: 4), ‘severely ill’ (CGI–S score: 5) and ‘among the most severely ill subjects’ (CGI–S score: 6) decreased from 55.7% at baseline to 11.9% at endpoint. From baseline to endpoint, 62.9% (214/340) of patients were much or very much improved, as assessed by the CGI–C scale.

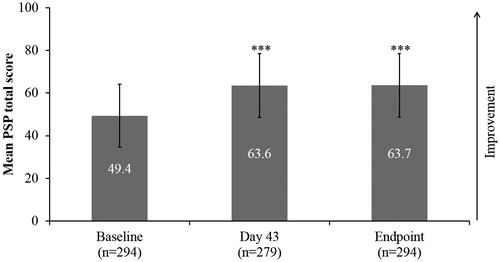

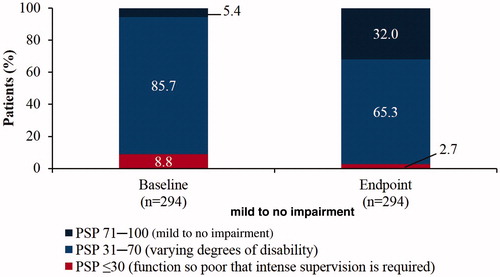

Statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements were observed in patient functioning (PSP total score) from baseline (49.4 ± 14.7) to endpoint (63.7 ± 14.9; mean change 14.3 ± 12.4, P < .0001; ). In addition, statistically significant improvements were observed in all four PSP domains from baseline to endpoint, P < .0001: socially useful activities (2.7 ± 1.2 vs 1.9 ± 1.1; mean change: –0.8 ± 1.0); personal and social relationships (2.5 ± 1.0 vs 1.6 ± 1.0; mean change: −0.9 ± 1.1); self-care (1.5 ± 1.2 vs 0.9 ± 1.1; mean change: −0.6 ± 1.0); and disturbing and aggressive behaviours (1.3 ± 1.3 vs 0.3 ± 0.7; mean change: −0.9 ± 1.2). The frequency of PSP functional impairment categories at baseline and endpoint is displayed in . At endpoint, 74.8% of patients showed an improvement of at least one ten-point category in the PSP scale

Figure 3. Patient functioning, as assessed by PSP total score (efficacy analysis set; n = 365). Statistically significant improvements were observed in PSP total score from baseline to Day 43 and to endpoint. ***Mean change P < .0001 vs baseline, Wilcoxon-signed rank test. Error bars represent SD. PSP: Personal and Social Performance.

Figure 4. Patient functioning as assessed by PSP three-category distribution (efficacy analysis set; n = 365). The proportion of patients categorised as having mild difficulty increased from baseline to endpoint. PSP: Personal and Social Performance.

At baseline, 23.7% (79/334) of patients were somewhat, very or extremely satisfied with their prior antipsychotic medication; whereas at endpoint, 80.9% (271/335) of patients were somewhat, very or extremely satisfied with PP1M treatment, as measured using the MSQ. At study endpoint, 41.4% (151/365) of patients were discharged from hospital.

Mean time from admission to first PP1M injection was 9.4 days (range 0–63). The estimated mean hospital stay (time from admission to first discharge) ± standard error was 41.7 ± 1.1 days. The estimated mean time from the first PP1M injection to first discharge was 30.1 ± 0.8 days. Of the 167 subjects discharged, five patients were discharged then re-hospitalised and discharged again and six patients were discharged and re-hospitalised afterwards.

Discussion

In the present study exploring safety, tolerability and treatment response of patients with schizophrenia admitted to hospital due to disease exacerbation, and who were initiated on PP1M treatment within the first 3 weeks of their hospital stay, PP1M treatment demonstrated a good safety and tolerability profile and was associated with an early, statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in psychotic symptoms, disease severity and patient functioning.

Treatment with PP1M was generally well tolerated during the 6-week observation period. The side-effect profile was consistent with the well-studied tolerability and safety profile of PP1M (Janssen Cilag et al. Citation2016), with no new safety issues identified.

In the current study, the main reason for initiating PP1M was partial/non-adherence to previous medication, similar to the findings of another naturalistic study of PP1M given in the inpatient and/or outpatient settings (Attard et al. Citation2014). LATs help with adherence issues (Brissos et al. Citation2014), and may improve patient outcomes, including reducing relapses (Schreiner et al. Citation2015) and hospitalisations (Kishimoto et al. Citation2013). A previous observational study of PP1M found that hospitalisations were significantly reduced following PP1M initiation (Taylor & Olofinjana Citation2014; Taylor et al. Citation2016). Consistent with those observations, in the current study, of the patients who were discharged, 93% remained discharged during the 6-week study period.

The majority of patients achieved a ≥30% and even a ≥50% improvement in BPRS total score, the latter being a recognised clinically meaningful improvement in acutely exacerbated patients (Leucht et al. Citation2005, Citation2006). Comparable PP1M treatment effects have been observed in other pragmatic studies of symptomatic, exacerbated patients (Hargarter et al. Citation2015) and non-acute patients with schizophrenia (Schreiner et al. Citation2014, Citation2015).

Important goals of therapy in acute schizophrenia are the reduction of psychotic symptoms and restoration of functioning (Hasan et al. Citation2012). Oral antipsychotic medications are recommended for the treatment of acutely exacerbated schizophrenia, whereas LATs are generally reserved for long-term maintenance of poorly adherent patients, and, as such, there is limited information on their initiation in a hospital setting. A study evaluating the efficacy of risperidone long-acting injectable therapy in hospitalised patients with acute schizophrenia found significant improvements versus placebo in reducing symptoms, as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score and individual PANSS factor scores: Positive symptoms, Negative symptoms and Disorganised thoughts (Lauriello et al. Citation2005). One reason why LATs may be perceived as not being suitable for treatment of acute schizophrenia is that they may take months to reach steady state (American Psychiatric Association Citation2010) and there is a need for rapid titration in severely ill patients (Brissos et al. Citation2014). Of note is that, although reaching steady-state plasma concentrations of PP1M may take several months, the approved initiation regimen allows for rapid achievement of therapeutic plasma concentrations within 2 weeks of starting PP1M treatment (Janssen Cilag et al. Citation2016). Accordingly, in the current study, most patients (88.8%) were initiated on PP1M about 9 days after hospital admission, and statistically significant and relevant improvements in psychotic symptoms (BPRS) and disease severity (CGI–S) were observed as early as 8 days after PP1M initiation (earliest timepoint measured in the study), indicating an early treatment effect. The early onset of treatment response observed in this study is in line with the results of an earlier randomised controlled trial of PP1M that demonstrated an early, statistically significant improvement in psychotic symptoms versus placebo (Bossie et al. Citation2011), even in markedly to severely ill patients with schizophrenia (Alphs et al. Citation2011). It should be noted, however, that PP1M is indicated without prior stabilisation on oral antipsychotics only if psychotic symptoms are mild to moderate (Janssen Cilag et al. Citation2016), and is not suitable for patients who require immediate symptom control. Paliperidone as a molecule has little sedating properties (Jones et al. Citation2010). Accordingly, during the present study, approximately 32% of patients received a benzodiazepine, which could be discontinued before the end of the study.

In addition to the improvements observed in psychotic symptoms, disease severity and patient functioning in this study, more patients were satisfied with PP1M treatment at endpoint than were satisfied with their prior oral antipsychotic at baseline. Treatment satisfaction has been recognised as an important aspect of determining treatment effectiveness (Juckel et al. Citation2014), and is also an important factor for treatment adherence (Atkinson et al. Citation2004; Fujikawa et al. Citation2008).

Although there has been conflicting evidence regarding the superiority of LATs over oral antipsychotics (Leucht et al. Citation2011; Kishimoto et al. Citation2013, Citation2014), the outcomes of these studies are highly related to the trial design (Kirson et al. Citation2013). Naturalistic and pragmatic studies, such as the current and other recent studies in acute (Hargarter et al. Citation2015) and non-acute patients with schizophrenia (Schreiner et al. Citation2014, Citation2015), provide valuable information in populations more akin to those encountered in routine clinical practice (Alphs et al. Citation2011), by allowing patients with relevant comorbidities, co-medications and substance abuse to be included.

The current study design was chosen to balance between the study objectives and the limitations of a non-interventional trial. This study did not aim to compare initiation of PP1M in the hospital setting with other treatments; rather, it explored PP1M as it is used in clinical routine, thus keeping the selection criteria to a minimum. Other potential limitations of the study include the possibility of inadvertent selection bias by physicians selecting patients who were more likely to respond to treatment; the open-label design, the lack of randomisation and the lack of a control group.

In conclusion, initiating PP1M in exacerbated patients with schizophrenia within 3 weeks of admission to hospital resulted in statistically significant improvements in symptoms and functioning, with an early onset of treatment response within 1 week of treatment. In addition, almost half the patients were very or extremely satisfied with PP1M treatment, which may in turn lead to improved treatment adherence. This naturalistic study provides valuable information on safety, tolerability and appropriate use of PP1M initiation in the hospital setting, and suggests that patients may benefit from early initiation of PP1M during the hospital stay.

Geolocation

This was an international study conducted in Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan and Russia.

Statement of interest

Dr Hargarter and Dr Schreiner are full-time employees of Janssen Cilag and are shareholders of Johnson & Johnson. Mr Cherubin is a full-time employee of Janssen Cilag. Dr Lahaye is a part-time employee of Janssen Cilag. Dr Tsapakis, Dr Joldygulov, Dr Lambert, Dr Vischia, Dr Swarz and Dr Chomskaya have no conflict of interest to declare. Dr Bozikas has received research support from, or has been an advisor to, or has received speaker’s honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Gallenica, Elpen, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, and Pharmaserve Lilly. This study was sponsored by Janssen Cilag.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the investigators who participated in the study, as well as Dr Irina Usankova for project execution management and her input during discussions regarding data interpretation. The study was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceutica NV. Medical writing assistance was provided by ApotheCom Ltd, London, and funded by Janssen Pharmaceutica NV.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alphs L, Bossie CA, Sliwa JK, Ma YW, Turner N. 2011. Onset of efficacy with acute long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate treatment in markedly to severely ill patients with schizophrenia: post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 10:12.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2010. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. [Internet]. [cited 2017 Apr]. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/schizophrenia.pdf

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Salkever D, Slade EP, Peng X, Conley RR. 2010. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 10:2.

- Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR. 2004. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2:12.

- Attard A, Olofinjana O, Cornelius V, Curtis V, Taylor D. 2014. Paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection-prospective year-long follow-up of use in clinical practice. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 130:46–51.

- Bitter I, Katona L, Zambori J, Takacs P, Feher L, Diels J, Bacskai M, Lang Z, Gyani G, Czobor P. 2013. Comparative effectiveness of depot and oral second generation antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a nationwide study in Hungary. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 23:1383–1390.

- Bossie CA, Sliwa JK, Ma YW, Fu DJ, Alphs L. 2011. Onset of efficacy and tolerability following the initiation dosing of long-acting paliperidone palmitate: post-hoc analyses of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 11:79.

- Brissos S, Veguilla MR, Taylor D, Balanza-Martinez V. 2014. The role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a critical appraisal. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 4:198–219.

- Chouinard G, Margolese HC. 2005. Manual for the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS). Schizophr Res. 76:247–265.

- Fujikawa M, Togo T, Yoshimi A, Fujita J, Nomoto M, Kamijo A, Amagai T, Uchikado H, Katsuse O, Hosojima H, et al. 2008. Evaluation of subjective treatment satisfaction with antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 32:755–760.

- Guy W. 1976. Clinical Global Impressions Scale. ECDEU Assessment Manual. [cited 2017 Apr]. Available from: https://www.psywellness.com.sg/docs/CGI.pdf

- Hargarter L, Cherubin P, Bergmans P, Keim S, Rancans E, Bez Y, Parellada E, Carpiniello B, Vidailhet P, Schreiner A. 2015. Intramuscular long-acting paliperidone palmitate in acute patients with schizophrenia unsuccessfully treated with oral antipsychotics. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 58:1–7.

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Moller HJ. 2012. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 13:318–378.

- Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M. 2013. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 3:200–218.

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations. 2012. Introductory guide: MedDRA version 15.1 [MSSO-DI-6003-15.1.0] [Internet]. Available from: http://www.meddra.org/sites/default/files/guidance/file/intguide_15_1_English_0.pdf

- Janssen Cilag. 2016. Paliperidone palmitate summary of product characteristics [Internet]. [cited 2017 Apr]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002105/WC500103317.pdf

- Jones MP, Nicholl D, Trakas K. 2010. Efficacy and tolerability of paliperidone ER and other oral atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 48:383–399.

- Juckel G, de Bartolomeis A, Gorwood P, Mosolov S, Pani L, Rossi A, Sanjuan J. 2014. Towards a framework for treatment effectiveness in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 10:1867–1878.

- Kamat SA, Offord S, Docherty J, Lin J, Eramo A, Baker RA, Gutierrez B, Karson C. 2015. Reduction in inpatient resource utilization and costs associated with long-acting injectable antipsychotics across different age groups of Medicaid-insured schizophrenia patients. Drugs Context. 4. doi:10.7573/dic.212267

- Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, Huang W, Samuelson T, Offord SJ, Greenberg PE, Wong BJO. 2013. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 74:568–575.

- Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. 2013. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 74:957–965.

- Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, Leucht S, Watanabe K, Mimura M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. 2014. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 40:192–213.

- Lauriello J, McEvoy JP, Rodriguez S, Bossie CA, Lasser RA. 2005. Long-acting risperidone vs. placebo in the treatment of hospital inpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 72:249–258.

- Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S. 2011. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia–a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 127:83–92.

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Etschel E, Kissling W, Hamann J, Engel RR. 2006. Linking the PANSS, BPRS, and CGI: clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology. 31:2318–2325.

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. 2005. Clinical implications of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Br J Psychiatry. 187:366–371.

- Malla A, Tibbo P, Chue P, Levy E, Manchanda R, Teehan M, Williams R, Iyer S, Roy M-A. 2013. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: recommendations for clinicians. Can J Psychiatry. 58:30S–35S.

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. 2000. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiat Scand. 101:323–329.

- Nasrallah HA. 2008. Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol Psychiatry. 13:27–35.

- National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. 2014. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults. The NICE guideline on treatment and management [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178

- Nicholl D, Nasrallah H, Nuamah I, Akhras K, Gagnon DD, Gopal S. 2010. Personal and social functioning in schizophrenia: defining a clinically meaningful measure of maintenance in relapse prevention. Curr Med Res Opin. 26:1471–1484.

- Novick D, Haro JM, Suarez D, Perez V, Dittmann RW, Haddad PM. 2010. Predictors and clinical consequences of non-adherence with antipsychotic medication in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 176:109–113.

- Overall J, Gorham D. 1962. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 10:799–812.

- Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, et al. 1999. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 56:241–247.

- Schennach R, Obermeier M, Meyer S, Jager M, Schmauss M, Laux G, Pfeiffer H, Naber D, Schmidt LG, Gaebel W, et al. 2012. Predictors of relapse in the year after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 63:87–90.

- Schreiner A, Bergmans P, Cherubin P, Keim S, Llorca P-M, Cosar B, Petralia A, Corrivetti G, Hargarter L. 2015. Paliperidone palmitate in non-acute patients with schizophrenia previously unsuccessfully treated with risperidone long-acting therapy or frequently used conventional depot antipsychotics. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford). 29:910–922.

- Schreiner A, Bergmans P, Cherubin P, Keim S, Rancans E, Bez Y, Parellada E, Carpiniello B, Vidailhet P, Hargarter L. 2014. A prospective flexible-dose study of paliperidone palmitate in nonacute but symptomatic patients with schizophrenia previously unsuccessfully treated with oral antipsychotic agents. Clin Ther. 36:1372–1388.e1371.

- Taylor D, Olofinjana O. 2014. Long-acting paliperidone palmitate - interim results of an observational study of its effect on hospitalization. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 29:229–234.

- Taylor DM, Sparshatt A, O'Hagan M, Dzahini O. 2016. Effect of paliperidone palmitate on hospitalisation in a naturalistic cohort - a four-year mirror image study. Eur Psychiatry. 37:43–48.

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, Haddad PM, Patel MX, Korhonen P. 2011. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 168:603–609.

- Vernon MK, Revicki DA, Awad AG, Dirani R, Panish J, Canuso CM, Grinspan A, Mannix S, Kalali AH. 2010. Psychometric evaluation of the Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) to assess satisfaction with antipsychotic medication among schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 118:271–278.