Abstract

Background

Levonorgestrel (LNG)-intrauterine devices (IUDs) are an effective method of contraception; however, there is growing evidence regarding potential psychiatric side effects such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review to summarise the psychiatric effects of using LNG-IUDs.

Methods

We searched six databases (MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo), and we included all study designs. The included studies were extracted, quality assessed, and qualitatively summarised.

Results

Out of the screened studies, only 22 were finally included. While ten studies showed increased depressive symptoms, two studies showed reduced symptoms. Moreover, one study showed increased anxiety, another one reported an increased risk of suicide, four studies concluded no association with depressive symptoms, and four other studies showed uncertainty about a potential association but mentioned other psychiatric symptoms.

Conclusion

Despite unreliable data, many studies report psychiatric symptoms associated with LNG-IUDs, predominantly depression. Gynaecologists, general practitioners, and psychiatrists should therefore be aware of these potential risks, especially depressive symptoms and suicidality. Counselling patients about these risks should be mandatory. Further studies should investigate the absolute risk of mental disorders associated with LNG-IUDs and other hormonal contraceptives.

Many researchers are reporting adverse psychiatric events associated with levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs).

Despite their effectiveness, a proper psychiatric assessment should be done before inserting LNG-IUDs.

Proper counselling regarding the depressive symptoms and suicidality should be done by the treating obstetrician.

Further studies should investigate the absolute risk of mental disorders associated with LNG-IUDs and other hormonal contraceptives.

KEY MESSAGES

Introduction

Several intrauterine devices (IUDs) have been available on the market for over thirty years (Kaiser Family Foundation Citation2020) and have been proven to be a popular choice with women in developed countries (World Health Organization Citation2020). The Levonorgestrel (LNG)-releasing-IUD is considered one of the most effective and safe methods of reversible contraception. These devices are classified as a progestin class of agents, which unfolds their effect in particular, by the release of the LNG in the cavum uteri (Sturridge and Guillebaud Citation1996; Beatty and Blumenthal Citation2009; Bednarek and Jensen Citation2010; Kaneshiro and Aeby Citation2010). LNG-IUDs exert their mechanism of action by the stimulation of the progesterone receptors carrying out two main functions (Salmi et al. Citation1998): firstly, they cause thickening of the cervical mucus, thus inhibiting the occurrence of fertilisation (Peck et al. Citation2016); secondly, LNG has a locally suppressive endometrial effect that results in minimal or indolent menstrual blood flow (Lu and Yang Citation2018). Moreover, the use of low-dose oestrogen combined with LNG-IUDs may improve common perimenopausal symptoms (Santoro et al. Citation2015). Solicited adverse reactions include menstrual cycle irregularities and/or abnormal menstrual bleeding (Mansour Citation2012). Owing to the local release of the drug in the uterine cavity, LNG-IUDs are thought to exert only a few systemic effects (Attia et al. Citation2013).

At present, there are three LNG-IUDs available: MirenaTM, KyleenaTM, and SkylaTM (Healthline Citation2022). MirenaTM releases 52 mcg/day of LNG, KyleenaTM 17.5 mcg/day, and SkylaTM 13.5 mcg/day of LNG. Of those, MirenaTM is the most commonly used LNG-IUD (Medscape Citation2022). Following the initial insertion of MirenaTM, 20 mcg/day are released for three months (Datapharm Citation2022). One year following the implantation of the IUD, approximately 18 mcg/day of LNG are released whereas only 10 and 9 mcg/day are released five years and six years post-insertion, respectively (Beatty and Blumenthal Citation2009).

The devices are considered safe with less pronounced side effects of LNG-IUDs than those with no hormonal components (Bednarek and Jensen Citation2010; Reinecke et al. Citation2018). However, depressive mood is one of the most frequent adverse effects, where between 1–100 and 1–10 users are affected (Datapharm Citation2022). Recent data from published studies have emerged on psychiatric symptoms or even disorders such as depression, emotional lability, panic attacks, and suicidal ideation in women using LNG-IUDs (Nilsson et al. Citation1982; Concin et al. Citation2009; Nelson Citation2017; Horibe et al. Citation2018; Skovlund et al. Citation2018; Langlade et al. Citation2019; Zeiss et al. Citation2020). Subsequently, a nationwide register study examined almost half a million women for an average of 8 years and linked the use of hormonal contraception (including LNG-IUDs) to a higher risk of suicide, especially among women in their adolescence (Skovlund et al. Citation2018). It is worth mentioning that non-pharmacological treatments such as enhancing exercise have been shown to be effective both in reducing mortality and treating symptoms of major depression (Belvederi Murri et al. Citation2018).

Despite several assumptions, the underlying etiopathological mechanisms of the association between psychiatric symptoms and hormonal contraception, in particular with LNG-IUDs are not fully understood and are still subject to research. One hypothesis comprises that LNG-IUDs potentiate the systemic response to psychosocial stress and induce a centrally mediated sensitisation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsivity with a subsequent increase in cortisol secretion (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). In addition, a recent study outlined the effects of progesterone and oestradiol on brain functioning within regions that regulate mood, as well as the effects of these sex hormones on neurotransmission within the serotonergic and dopaminergic system, relevant in the pathophysiology of depression (Nutt Citation2008; Rio et al. Citation2018). Motivated by this controversial data and the ongoing debate on this topic, we conducted a systematic review to delineate any potential associations between the use of LNG-IUDs and psychiatric adverse reactions in the current scientific literature.

Methods

Search strategy and database searching

We searched the databases PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and PsycInfo on the 6th of October 2022 for the association between LNG-IUD and psychiatric symptoms. A broad search strategy was followed to cover most of the available literature. The search strategy for all databases was (‘Norgestrel’ OR ‘Mirena’ OR ‘Norplant’ OR ‘Plan B’ OR ‘NorLevo’ OR ‘Norplant2’ OR ‘Cerazet’ OR ‘Capronor’ OR ‘Microlut’ OR ‘Microval’ OR ‘Levonorgestrel’ OR’ LNG-IUS’ OR ‘Hormonal contraception’) AND (‘Panic attacks’ OR ‘Panic disorder’ OR ‘Depression’ OR ‘Depressive disorder’ OR ‘Suicide’) except for ScienceDirect, which was (‘LNG-IUD’ OR’ LNG-IUS’) AND (‘Panic attacks’ OR ‘Panic disorder’ OR ‘Depression’ OR ‘Depressive disorder’ OR ‘Suicide’). The search was conducted by using the title and abstract filters in all databases except for PubMed Web of Science, which were set to include all fields.

Selection criteria

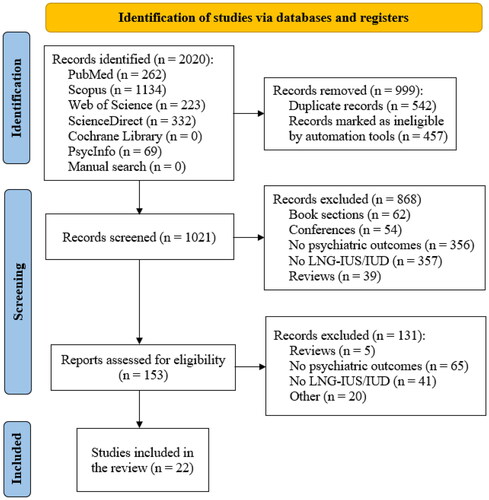

Inclusion criteria: All kinds of peer-reviewed studies, including case series/reports, examining the association between LNG-IUDs and the occurrence of the above-mentioned psychiatric symptoms or disorders. Exclusion criteria: Studies that did not involve LNG-IUDs, animal studies, conference papers, and non-English studies. We followed the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) criteria (Page et al. Citation2021) for study selection () and the PICO (‘Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome’) schema for systematic reviews as follows:

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram that depicts the search process and the number of retrieved articles for inclusion in this review.

Population: Women of childbearing age

Intervention: Using Levonorgestrel-IUD

Comparison: None

Outcome: Psychiatric disorders (depressive symptoms/anxiety/suicidal attempts).

Screening and data extraction

Three authors (KT, ME, AE) performed the screening independently. The process consisted of two steps, first a title and abstract screening, then studies were screened for eligibility and relevance by reviewing the full texts. Three researchers examined full texts and reviewed them for relevance (ME, AE, CS-L). Five researchers (KT, ME, NK, IP, AE) extracted relevant information from the included studies. References of included studies were screened for additional relevant studies not included in the initial search process. The main outcome was the association between LNG-IUD and the occurrence of depression or other psychiatric disorders ( PRISMA flow diagram).

Quality assessment

Two authors (KT and ME) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. Any disagreement was referred to a senior study member (CS-L). Four tools were used for the quality assessment of included studies: (i) NIH tool for Quality Assessment of Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies; (ii) NIH tool for Quality Assessment Tool for before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group; (iii) Newcastle Ottawa scale for non-randomised trials (NOS) and (iv) Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool for randomised clinical trials. The NOS tool consists of three main domains: selection, comparability, and exposure. The total score is given out of 9. Studies were deemed high quality if the score was 7–9, fair quality for 4–6, and low quality for 0–3. The NIH tools are composed of 14 criteria for cross-sectional studies and 12 criteria for prospective studies with no control group. Cross-sectional and observational studies were deemed high quality if they scored 11 or more, fair quality for 7–11, and poor quality if the score was lower than 7. The quality of prospective studies with no control was considered high quality (if 9 or more), fair quality (if 6–9), and poor quality (if scores were lower than 6). The RoB 2 assesses the quality of randomised trials based on several domains: randomisation process, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel and participants, blinding of assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting of outcomes, and other biases. The scoring for each domain is divided into low risk, some concerns of bias, and high risk.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 2020 studies were primarily found from our search. Half of them (999) were excluded using EndNote 20 software. After the further exclusion of 996 studies for the reasons depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (), twenty-two studies were included in this systematic review. Ten studies showed a positive association between LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms while four showed no association, and two showed a negative association. The summary of the included studies is shown in , while the characteristics of the included studies are shown in and .

Table 1. Summary of the included studies.

Table 2. Characteristics of the included study (Part 1).

Table 3. Characteristics of the included study (Part 2).

LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms

Positive association

A total of 10 studies showed increased depressive symptoms among LNG-IUD users.

In a pharmacovigilance database study comprising 3224 case reports of women with LNG-IUD, 38.8% of the reports were related to anxio-depressive disorders after the media coverage peak (Langlade et al. Citation2019).

A retrospective study based on data from the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system investigated the association of postpartum depression and several drugs including contraceptive devices and implants between 2004 and 2015 in spontaneously reported adverse events. 34 reports of postpartum depression were detected from a total of 75,500 cases among LNG-IUD users (Horibe et al. Citation2018).

A retrospective study conducted via a questionnaire by Backman et al. demonstrated a strong association between early removal of LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms (Backman et al. Citation2005). This study investigated 17914 women in Finland with the insertion of LNG-IUDs between April 1990 and December 1993. A multivariate analysis was conducted via Cox Hazard Model and premature removal of the LNG-IUDs was strongly associated with depression in some women.

A phase 3 multicenter study conducted in the United Kingdom by Cox et al. in a clinical setting studied the performance and effectiveness of LNG-IUD in 678 women (Cox et al. Citation2002). Of those, 13 women presented with depressive symptoms.

An open randomised multicenter study was conducted by Andersson et al. to examine the effectiveness of 20 mcg/24 h LNG-IUD compared to Nova T (a copper-releasing device) for the duration of its course (5 years) (Andersson et al. Citation1994). In this study, 1821 women were included in the LNG-IUD group and 937 women in the Nova T group. In terms of hormonal disturbances, the LNG-IUD group had a termination rate of 2.9 compared to the Nova T group (2.0, p < 0.001). A study conducted by Nilsson et al. revealed significant results for Nervousness (Nilsson et al. Citation1982).

Absence of an association

Four studies revealed no association between the use of LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms.

In particular, Toffol et al. performed a cross-sectional population-based health survey in Finland that concluded the absence of an association between LNG-IUD use and Beck Depression Inventory-13 (BDI-13) scores (Toffol et al. Citation2012). Enzlin et al. performed a multicenter study on more than 350 women using LNG-IUD and no difference in psychological symptoms was observed in comparison to users of Cu-IUD (Enzlin et al. Citation2012). Besides, Tazegül et al. performed a study on 120 premenopausal women that received LNG-IUDs in which depression scores did not show a significant difference from the baseline (Tazegül Pekin et al. Citation2014). Toffol et al. observed no association between the use of LNG-IUDs and depressive symptoms (Toffol et al. Citation2011).

Negative association

Two of the studies showed a negative association between LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms/depression. A retrospective study by Roberts et al. consisting of 75,528 postpartum women with depression and subsequent antidepressant use revealed that postpartum women using LNG-releasing contraceptives had a lower risk of being diagnosed with depression (Roberts and Hansen Citation2017). A reduction of depressive symptoms with hormonal IUD was observed in Keyes et al. population-based, longitudinal analysis study (Keyes et al. Citation2013).

LNG-IUD and anxiety

A cohort study conducted by Slattery et al. studied the effects of hormonal IUDs on new users of LNG-IUDs compared to non-hormonal IUDs and their association with anxiety and sleep disturbances in subjects with no medical psychiatric history (Slattery et al. Citation2018). This study revealed a significant association between LNG-IUD with anxiety and sleep disturbances indicating a hazard ratio of 1.18 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.08–1.29 for anxiety. Regarding sleep disturbances, they observed a hazard ratio of 1.22 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.08–1.38. The results for restlessness or panic attacks were not significant.

LNG-IUD and suicide

A nationwide prospective cohort study conducted by Skovlund et al. in Denmark studied the relative risk of suicide and suicide attempts in 475,802 women over the age of 15 using hormonal contraceptives from 1996-2013 (23). The women in this study did not have a psychiatric or medical history (Skovlund et al. Citation2018). Numerous confounding variables were extracted. Approximately half a million women were followed for 8.3 years with a mean age of 21 years. Results indicated 6999 initial suicide attempts and 71 suicides. Relative risk was the highest in adolescents. The relative risk of suicide attempt of hormonal contraceptive use was 2.06 (95% CI = 1.92–2.21) in women between the age of 15-19 years (Skovlund et al. Citation2018). In the 20-24 year-old age group, the relative risk was 1.61 (95% CI = 1.39–1.85), and 1.64 (95% CI = 1.14–2.36) for the 25–33 age group (Skovlund et al. Citation2018). In addition, the relative risk of initial suicide attempts increased considerably following the insertion of hormonal contraceptives for one year and decreased thereafter in comparison to the non-users (Skovlund et al. Citation2018).

Other related studies

Several studies have also been conducted in the past to study the effects of LNG-IUD (Heikinheimo et al. Citation2014; Eisenberg et al. Citation2015; Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). A partially randomised trial conducted by Eisenberg et al. studied the three-year efficacy and safety of 52mg LNG-IUD in 1751 women between the ages of 15 and 45; 1600 women were between the ages of 16 and 35 and 151 women were 36–45 years of age. Depressive symptoms were one of the adverse effects noted in 94 (5.4%) of the women among all participants in this study (Eisenberg et al. Citation2015). However, it was also here unclear in the Eisenberg et al. study or the other studies whether depressive symptoms were associated with the LNG-IUD or other confounding variables (Heikinheimo et al. Citation2014; Eisenberg et al. Citation2015; Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017).

A cross-sectional study and two experimental studies were conducted by Aleknaviciute et al. that investigated each woman from three different groups: women with LNG-IUD, women taking oral ethinyl oestradiol and levonorgestrel and women with natural cycling and no hormonal contraceptives (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). In study 1, repeated measurements (including baseline) of salivary cortisol levels were conducted in all groups following the established Trier Social Stress Test (TSST). Study 2 investigated salivary cortisol and serum total cortisol between these groups following the administration of 1 mcg ACTH. Study 3 assessed hair cortisol to draw any conclusion on the prolonged or long-term effects of cortisol. A significant increase in salivary cortisol was observed in women with LNG-IUD following the TSST compared to the other groups (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). Heart rates, ACTH challenge, and cortisol hair levels were also significantly higher in the LNG-IUD group. In summary, these results were interpreted as a hypersensitivity of the autonomic HPA axis in presence of psychosocial stress owing to the use of LNG-IUD.

Quality assessment

A total of 22 studies were assessed for their quality of evidence. Four RCTs were assessed by RoB 2 tool, 3 prospective studies with no control group were assessed by the NIH tool, 3 case-control studies were assessed by NOS, and 12 observational and cross-sectional studies were assessed by the respective NIH tool. The included RCTs showed an overall low risk of bias with some concerns regarding the blinding of personnel in Andersson et al. (Citation1994) and Sivin and Stern (Citation1994) (). As for the prospective studies, Heikinheimo et al. (Citation2014) and Elovainio et al. (Citation2007) were deemed of high quality while Cox et al. (Citation2002) was of fair quality (). For the case-control studies, Slattery et al. (Citation2018) was of high quality while Aleknaviciute et al. (Citation2017) and Enzlin et al. (Citation2012) were deemed of fair quality (). As for the remaining studies, Skovlund et al. (Citation2018), Skovlund et al. (Citation2016), Tazegül Pekin et al. (Citation2014), Toffol et al. (Citation2012), Daud and Ewies (Citation2008), Robinson et al. (Citation2008), and Backman et al. (Citation2005) were assessed to be of high quality while Langlade et al. (Citation2019), Horibe et al. (Citation2018), Roberts and Hansen (Citation2017), Keyes et al. (Citation2013), and Toffol et al. (Citation2012) were deemed as of moderate quality ().

Table 4. Cochrane ROB2 tool for assessment of randomised trials.

Table 5: NIH prospective studies with no control group.

Table 6. New castle Ottawa scale for non-randomised studies.

Table 7. NIH for observational and cross-sectional studies.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review to study the hypothesis that LNG-IUD might be associated with a higher risk of psychiatric symptoms, such as depressive and/or anxiety symptoms.

Following the PRISMA criteria as an evidence-based minimum set for reporting systematic reviews, twenty-two studies were included in the final analyses and showed ambiguous results, but a greater number of them reported a positive association with depressive symptoms related to LNG-IUDs.

According to a pharmacovigilance database study for Mirena® reports, 38.8% of the reports after the media coverage peak were related to symptoms of anxiety and depression (Langlade et al. Citation2019). A questionnaire on the reproductive and contraceptive history of over 17,000 users of LNG-IUD revealed that 36% of the LNG-IUD users reported depressive symptoms. An open-label, partially randomised trial on 1600 women who received LNG-IUD observed that 5.4% reported depression or depressed mood (Eisenberg et al. Citation2015).

Anxiety, mood, sleep disturbances, restlessness, and suicidal attempts were also reported in the previous literature (Tazegül Pekin et al. Citation2014; Bitzer et al. Citation2018; Slattery et al. Citation2018). Despite these aforementioned adverse effects, LNG-releasing IUDs are broadly used due to patient satisfaction and effectiveness (Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group TACoO, Gynecologists Citation2012). However, previous research showed that depression and mood swings were among the leading causes of discontinuation of LNG-releasing IUDs (Backman et al. Citation2000; Cox et al. Citation2002; Elovainio et al. Citation2007; Daud and Ewies Citation2008; Eisenberg et al. Citation2015; Hall et al. Citation2015). This is in line with the results of Elovaino et al. (Citation2007) and Heikinheimo et al. (Citation2014). Large doses of synthetic oestrogens and progestins in combined oral contraceptive tablets (COCs) (e.g. Enovid: 5 mg norethynodrel, 75 mcg mestranol) were thought to interact with mood-related neurotransmitters and neurotransmitter metabolism by contraceptive researchers in the 1960s and 1970s (Hall et al. Citation2015). Female reproductive physiology and hormonal disturbances can be attributed to the higher risk of depression in women compared to men (Soares and Zitek Citation2008). During puberty, pregnancy, postpartum, and menopause, women are more vulnerable to experiencing fluctuations in their mood, such as depressive manifestations (Soares and Zitek Citation2008).

The pathophysiological mechanism of depression as an adverse event of LNG-IUD use might be linked to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to LNG (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, central sensitisation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to lead to raised heart rate and higher cortisol levels, even in comparison to oral contraceptives, the copper spiral, or the natural cycle (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). We believe that the reported studies of women who complained of mood swings after using LNG-IUDs should be correlated with the evidence that the LNG-IUD potentiates increased but relatively low serum levels of levonorgestrel, which could exert systemic adverse effects. Furthermore, women with a positive history of depression might be more vulnerable to these adverse events. Therefore, LNG-IUD might be not the first choice in this risk group. It is worth mentioning that Bosco-Lévy and colleagues matched a cohort of 9318 LNG-IUS users with 10,185 copper-IUD and analysed new initiation of psychiatric drugs or a new psychiatric visit among other adverse effects. They found that the LNG-IUD cohort had a tendency to initiate anxiolytic drugs more than the copper-IUD counterparts (HR 1.08, 95%CI 1.01–1.15), probably because of having more anxiety and depressive symptoms than the copper-IUD users. Furthermore, a slight increase in device removal was observed in the LNG-IUD users (Bosco-Levy et al. Citation2019).

Noteworthy, the possible predictive value of affective temperamental dysregulation might be a possible contributor to negative clinical outcomes in depressed patients. Importantly, patients with higher total scores on affective dysregulated temperaments are more likely to have higher hopelessness which is an important predictor of suicidality. Importantly, 67% of patients in the dysregulated group had Beck Hopelessness Scale total scores indicating high levels of hopelessness (Serafini et al. Citation2012). Despite several assumptions, the underlying etiopathological mechanisms of the association between psychiatric symptoms and hormonal contraception, in particular with LNG-IUD remain unclear and are still the subject of research.

Considering the pharmacokinetic properties of LNG-IUDs, in particular, the insertion is followed by a significant increase in serum LNG levels that may contribute to the negative effects of LNG-IUDs on mental health (Hall et al. Citation2015). Thus, one can assume that also the replacement of LNG-IUD is accompanied by a higher risk of (mental) side effects. In line with this assumption, we recently reported a case of developing psychiatric symptoms, e.g. depressive mood, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in association with the replacement of the LNG-IUD (Healthline Citation2022).

In contrast, some studies showed the opposite direction in findings. A cross-sectional population-based health survey in Finland showed no association between the use of LNG-IUD and depressive symptoms assessed by Beck Depression Inventory-13 (BDI-13) scores (Toffol et al. Citation2012). A completed Study Survey investigated the effects of current use and the duration of hormonal contraceptives including LNG-IUD on mood and psychological symptoms and found that hormonal contraception is not associated with a negative influence on mental health (Toffol et al. Citation2012). Enzlin et al. did not observe a difference in psychological symptoms among LNG-IUD users versus Cu-IUD users (Enzlin et al. Citation2012). Also, in line with this, Tazegül et al. observed no significant difference in depressive scores among 120 premenopausal women through the first six months after LNG-IUD insertion; there were no significant differences in depression scales in women that received LNG-IUD compared to the time before insertion (Tazegül Pekin et al. Citation2014). Moreover, some studies reported a negative relationship between depressive symptoms and the use of LNG-IUDs. Toffol et al. (Citation2011) reported a negative association between LNG-IUD and Beck Depression inventory total score. In addition, Keyes et al. performed a study on more than 6000 sexually active women in the United States and observed that women that used IUDs for contraception, did not have an association with depressive symptoms, however no information if the IUDs contained hormones were available; Keyes et al. also reported a reduction of depressive symptoms with hormonal IUD (Keyes et al. Citation2013).

Böttcher et al. performed a survey on MEDLINE/PubMed and found that depression was not a common side effect of hormone-based contraception (Bottcher et al. Citation2012). A previous review of the literature showed that the majority of women using hormonal contraception did not experience mood-related alterations (Smiech and Rabe-Jabłońska Citation2006). The rates of mood symptoms were similar, or even lower than women who did not use hormonal contraception (McCloskey et al. Citation2021). Worly et al. performed a systematic review of 26 articles and found no evidence of LNG-IUD-associated depression (Worly et al. Citation2018). This correlates with the results of Toffol et al. who performed a cross-sectional approach using data from previous surveys and also did not find an association between LNG-IUD and depression (Toffol et al. Citation2012). A systematic review of the literature from Ti et al. found no association between hormonal contraception and postpartum depression (Ti and Curtis Citation2019). In addition, an observational study of 120 premenopausal women who received LNG-IUD did not show a significant increase in the depression scores (Short-Form Health Survey) (SF-36) and Beck's Depression Inventory after six months follow-up (Tazegül Pekin et al. Citation2014). A secondary analysis of insurance records in more than 75,000 postpartum women showed that the use of LNG-IUS was associated with a lower risk of depression (Roberts and Hansen Citation2017). Here it is important to emphasise that postpartum women that have used antidepressants or were diagnosed with depression in the two years preceding delivery, were excluded from the study (Roberts and Hansen Citation2017). Schaffir et al. performed a MEDLINE review on combined hormonal contraception in the past 30 years and found that their effect on mood was rather infrequent (Schaffir et al. Citation2016). In addition, Bürger et al. concluded through a systematic review that LNG-IUD use improves the quality of life and sexual function (Burger et al. Citation2021). Moreover, Pagano et al. found that women with pre-existing depression did not suffer from the worsening of clinical course of depression following the use of LNG-IUD (Pagano et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, Enzlin et al. performed a cross-sectional study and observed that depressive symptoms did not differ between women using LNG-IUD versus copper IUD (Enzlin et al. Citation2012).

Gopimohan et al. analysed a cohort of women aged 30–50 years who were referred for abnormal uterine bleeding. The women had an insertion of LNG-IUD and were followed up for 6 months. The main outcomes were menstrual blood loss and quality of life (assessed using the EQ-5D-3 L questionnaire). The questionnaire measures several quality-of-life aspects including depression. A score improvement was found pre and post-intervention, however, it was not clear whether the domain of mental health is the one responsible for the statistically significant improvement (Gopimohan et al. Citation2015).

In addition, Hurskainen et al. conducted a randomised trial in which 236 women were enrolled for treatment of menorrhagia and followed up for 5 years. One-hundred-and-nineteen had insertion of LNG-IUD while the rest received a hysterectomy. Depressive and anxiety symptoms were improved in both groups after 5 years of follow-up, indicating that the main cause of these symptoms was the disease (whether the indication of hysterectomy or the cause of menorrhagia). Furthermore, no significant differences in depression or anxiety symptoms were found between both cohorts pre or post-intervention (Hurskainen et al. Citation2004).

Hence, counselling women who have been recognised as being at higher risk of developing psychiatric symptoms is essential. Finally, it should be noted that major depressive disorder is a multifactorial disease, where the hormonal imbalance imposed by the LNG-IUD is only part of the aetiology. This means that the association depicted in the studies included in this review does not mean direct causation of illness in all patients. This can be explained by the wide heterogeneity in the included studies.

Limitations

This work attempted to describe and discuss the current literature on LNG-IUD and its association with psychiatric disorders. Some limitations of our analysis are: The study is solely based on published articles. In concern to progestin contraceptives, previous literature did not show evidence of increased depression through the use of progestin contraceptives (Attia et al. Citation2013). Larger blood samples should be investigated during the luteal phase. Furthermore, affective symptoms were not assessed in some studies (Aleknaviciute et al. Citation2017). Potential confounding factors, such as major life events, sexual relationships, and previous mental health problems, are all possible issues that could influence the results of the studies of the LNG-IUD in relation to psychiatric symptoms. Besides, the included studies had various age groups, in which the relative risk of depression might vary between different age groups. In addition, the time since the placement of the LNG-IUD probably varied between the studies. Furthermore, the focus of this study was only on psychological adverse events. Other adverse events related to LNG-IUDs, for example, breast cancer (Conz et al. Citation2020), were not assessed.

In the meantime, further research is required to further assess the potential association between mood disorders and hormonal contraception. Differentiation of LNG-IUD from oral contraception use and its potential adverse effects should be thoroughly examined in future studies to clearly understand the respective psychiatric complications each may ensue.

Conclusion

Despite controversial information in the literature, an association between LNG-IUD use and depressive/anxiety symptoms or disorders seems to exist considering the selected studies, even if not all studies report such a connection. The causative relationship between symptoms and LNG-IUD is not fully understood yet but is probably due to the sensitisation of central structures that regulate the stress axis of the brain. This review might be interpreted with care and could not be generalised, keeping in mind that the number of reports of depression or anxiety is still considered very low, explaining the current controversial debate regarding LNG-IUD, which is known to be one of the most effective, safe, widely used contraceptive methods worldwide (Bednarek and Jensen Citation2010). The findings of this review have some main implications, such as the importance of better communication between physicians and patients about potential adverse events, including depression or mood disorders, which might help reduce the fear of women from using levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs. Moreover, we believe it is mandatory to accurately pay attention to the psychiatric history before insertion of LNG-IUD and to follow up on potential psychiatric adverse events after counselling the patient. Insights into the timing and response to removal measures for symptom management other than removal, such as treatment of underlying mood disorders (both pharmaceutical and psychological techniques), and the potential benefits of early follow-up visits are required. Nonetheless, patients should be counselled about the risks and benefits of the potential LNG-IUD options apart from pregnancy prevention. This literature review can further aid healthcare providers in sufficiently informing their patients of the known adverse effects to make sound decisions and prevent unforeseen circumstances. Finally, further research that employs randomised controlled trials is needed to allow a more definitive assessment of the effects of contraception on women's mental health.

Author contributions

ME developed the idea. ME and HG performed the database search. KT, ME, NK, IP, and CS-L screened the articles for inclusion, extracted the data, and performed the quality assessment. KT performed the data analysis. All authors wrote the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission for publication. The study process was monitored by ME.

Acknowledgments

No one other than the listed authors contributed to this work.

Statement of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge, or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. None to declare.

Data availability statement

All the data used for the conduction of this study are readily available from the articles included in the analysis. However, the data collected can be obtained by contacting the first author (Dr. Mohmed Elsayed at [email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aleknaviciute J, Tulen JHM, De Rijke YB, Bouwkamp CG, van der Kroeg M, Timmermans M, et al. 2017. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device potentiates stress reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 80:39–45.

- Andersson K, Odlind V, Rybo G. 1994. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use: a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 49(1):56–72.

- Attia AM, Ibrahim MM, Abou-Setta AM. 2013. Role of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in effective contraception. Patient Prefer Adherence. 7:777–785.

- Backman T, Huhtala S, Blom T, Luoto R, Rauramo I, Koskenvuo M. 2000. Length of use and symptoms associated with premature removal of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system: a nation-wide study of 17,360 users. BJOG. 107(3):335–339.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Jaakkola K, Inki P, Vaahtera K, Launonen A, Koskenvuo M. 2005. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol.;106(4):813–817.

- Beatty MN, Blumenthal PD. 2009. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 5(3):561–574.

- Bednarek PH, Jensen JT. 2010. Safety, efficacy and patient acceptability of the contraceptive and non-contraceptive uses of the LNG-IUS. Int J Womens Health. 1:45–58.

- Belvederi Murri M, Ekkekakis P, Magagnoli M, Zampogna D, Cattedra S, Capobianco L, Serafini G, Calcagno P, Zanetidou S, Amore M. 2018. Physical exercise in major depression: reducing the mortality gap while improving clinical outcomes. Front Psychiatry. 9:762.

- Bitzer J, Rapkin A, Soares CN. 2018. Managing the risks of mood symptoms with LNG-IUS: a clinical perspective. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 23(5):321–325.

- Bosco-Levy P, Gouverneur A, Langlade C, Miremont G, Pariente A. 2019. Safety of levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system compared to copper intrauterine device: a population-based cohort study. Contraception. 99(6):345–349.

- Bottcher B, Radenbach K, Wildt L, Hinney B. 2012. Hormonal contraception and depression: a survey of the present state of knowledge. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 286(1):231–236.

- Burger Z, Bucher AM, Comasco E, Henes M, Hubner S, Kogler L, Derntl B. 2021. Association of levonorgestrel intrauterine devices with stress reactivity, mental health, quality of life and sexual functioning: a systematic review. Front Neuroendocrinol. 63:100943.

- Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group TACoO, Gynecologists. 2012. Committee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 120(4):983–988.

- Concin H, Bosch H, Hintermuller P, Hohlweg T, Mursch-Edlmayr G, Pinnisch B, Schmidl-Amann S, Schulz-Greinwald G, Unterlerchner D, Wagner T. 2009. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: an Austrian perspective. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 21(Suppl 1):s1–s9.

- Conz L, Mota BS, Bahamondes L, Teixeira Doria M, Francoise Mauricette Derchain S, Rieira R, Sarian LO. 2020. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 99(8):970–982.

- Cox M, Tripp J, Blacksell S. 2002. Clinical performance of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system in routine use by the UK Family Planning and Reproductive Health Research Network: 5-year report. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 28(2):73–77.

- Datapharm. Mirena 20 micrograms/24 hours intrauterine delivery system; 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1132#gref.

- Daud S, Ewies AA. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: why do some women dislike it? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(12):686–690.

- Del Rio JP, Alliende MI, Molina N, Serrano FG, Molina S, Vigil P. 2018. Steroid hormones and their action in women's brains: the importance of hormonal balance. Front Public Health. 6:141.

- Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, Teal SB, Westhoff CL, Creinin MD, ACCESS IUS Investigators. 2015. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception.;92(1):10–16.

- Elovainio M, Teperi J, Aalto AM, Grenman S, Kivela A, Kujansuu E, Vuorma S, Yliskoski M, Paavonen J, Hurskainen R. 2007. Depressive symptoms as predictors of discontinuation of treatment of menorrhagia by levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Int J Behav Med. 14(2):70–75.

- Enzlin P, Weyers S, Janssens D, Poppe W, Eelen C, Pazmany E, Elaut E, Amy J.-J. 2012. Sexual functioning in women using levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems as compared to copper intrauterine devices. J Sex Med. 9(4):1065–1073.

- Gopimohan R, Chandran A, Jacob J, Bhaskar S, Aravindhakshan R, Aprem AS. 2015. A clinical study assessing the efficacy of a new variant of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system for abnormal uterine bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 129(2):114–117.

- Hall KS, Steinberg JR, Cwiak CA, Allen RH, Marcus SM. 2015. Contraception and mental health: a commentary on the evidence and principles for practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 212(6):740–746.

- Healthline. 2022. Choosing the right IUD: Mirena, Skyla, Liletta, Kyleena, or Paragard? https://www.healthline.com/health/birth-control/mirena-paragard-skyla.

- Heikinheimo O, Inki P, Schmelter T, Gemzell-Danielsson K. 2014. Bleeding pattern and user satisfaction in second consecutive levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system users: results of a prospective 5-year study. Hum Reprod. 29(6):1182–1188.

- Horibe M, Hane Y, Abe J, Matsui T, Kato Y, Ueda N, Sasaoka S, Motooka Y, Hatahira H, Hasegawa S. 2018. Contraceptives as possible risk factors for postpartum depression: a retrospective study of the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system, 2004–2015. Nurs Open. 5(2):131–138.

- Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, Aalto AM, Grenman S, Kivela A, Kujansuu E, Vuorma S, Yliskoski M, Paavonen J. 2004. Clinical outcomes and costs with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: randomized trial 5-year follow-up. JAMA. 291(12):1456–1463.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. Intrauterine devices (IUDs): access for women in the U.S. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/intrauterine-devices-iuds-access-for-women-in-the-u-s/.

- Kaneshiro B, Aeby T. 2010. Long-term safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability of the intrauterine copper T-380A contraceptive device. Int J Womens Health. 2:211–220.

- Keyes KM, Cheslack-Postava K, Westhoff C, Heim CM, Haloossim M, Walsh K, Koenen K. 2013. Association of hormonal contraceptive use with reduced levels of depressive symptoms: a national study of sexually active women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 178(9):1378–1388.

- Langlade C, Gouverneur A, Bosco-Levy P, Gouraud A, Perault-Pochat MC, Bene J, Iremont-Salamé G, Pariente A, French Network of Pharmacovigilance Centres. 2019. Adverse events reported for Mirena levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in France and impact of media coverage. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 85(9):2126–2133.

- Lu M, Yang X. 2018. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia: illustrated case series. BMC Womens Health. 18(1):45.

- Mansour D. 2012. The benefits and risks of using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for contraception. Contraception. 85(3):224–234.

- McCloskey LR, Wisner KL, Cattan MK, Betcher HK, Stika CS, Kiley JW. 2021. Contraception for women with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 178(3):247–255.

- Medscape. 2022. Drugs & diseases – levonorgestrel intrauterine (Rx). https://reference.medscape.com/drug/mirena-skyla-levonorgestrel-intrauterine-342780.

- Nelson AL. 2017. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS 12) for prevention of pregnancy for up to five years. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 10(8):833–842.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. 1982. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 25(4):345–56.

- Nutt DJ. 2008. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 69(Suppl E1):4–7.

- Pagano HP, Zapata LB, Berry-Bibee EN, Nanda K, Curtis KM. 2016. Safety of hormonal contraception and intrauterine devices among women with depressive and bipolar disorders: a systematic review. Contraception. 94(6):641–649.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n71.

- Peck R, Rella W, Tudela J, Aznar J, Mozzanega B. 2016. Does levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive have a post-fertilization effect? A review of its mechanism of action. Linacre Q. 83(1):35–51.

- Reinecke I, Hofmann B, Mesic E, Drenth HJ, Garmann D. 2018. An integrated population pharmacokinetic analysis to characterize levonorgestrel pharmacokinetics after different administration routes. J Clin Pharmacol. 58(12):1639–1654.

- Roberts TA, Hansen S. 2017. Association of hormonal contraception with depression in the postpartum period. Contraception. 96(6):446–452.

- Robinson R, China S, Bunkheila A, Powell M. 2008. Mirena intrauterine system in the treatment of menstrual disorders: a survey of UK patients' experience, acceptability and satisfaction. J Obstet Gynaecol. 28(7):728–731.

- Salmi A, Pakarinen P, Peltola AM, Rutanen EM. 1998. The effect of intrauterine levonorgestrel use on the expression of c-JUN, oestrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and Ki-67 in human endometrium. Mol Hum Reprod. 4(12):1110–1115.

- Santoro N, Teal S, Gavito C, Cano S, Chosich J, Sheeder J. 2015. Use of a levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system with supplemental estrogen improves symptoms in perimenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause. 22(12):1301–1307.

- Schaffir J, Worly BL, Gur TL. 2016. Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 21(5):347–355.

- Serafini G, Pompili M, Innamorati M, Gentile G, Borro M, Lamis DA, Lala N, Negro A, Simmaco M, Girardi P, et al. 2012. Gene variants with suicidal risk in a sample of subjects with chronic migraine and affective temperamental dysregulation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 16(10):1389–1398.

- Sivin I, Stern J, International Committee for Contraception Research (ICCR). 1994. Health during prolonged use of levonorgestrel 20 micrograms/d and the copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devices: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 61(1):70–77.

- Skovlund CW, Morch LS, Kessing LV, Lange T, Lidegaard O. 2018. Association of hormonal contraception with suicide attempts and suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 175(4):336–342.

- Skovlund CW, Morch LS, Kessing LV, Lidegaard O. 2016. Association of hormonal contraception with depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 73(11):1154–1162.

- Slattery J, Morales D, Pinheiro L, Kurz X. 2018. Cohort study of psychiatric adverse events following exposure to levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices in UK general practice. Drug Saf. 41(10):951–958.

- Smiech A, Rabe-Jabłońska J. 2006. Psychiatric disorders connected with hormonal contraception. Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna. 6:110–117 + 32.

- Soares CN, Zitek B. 2008. Reproductive hormone sensitivity and risk for depression across the female life cycle: a continuum of vulnerability? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 33(4):331–343.

- Sturridge F, Guillebaud J. 1996. A risk-benefit assessment of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Drug Saf. 15(6):430–440.

- Tazegul Pekin A, Secilmis Kerimoglu O, Kebapcilar AG, Yilmaz SA, Benzer N, Celik C. 2014. Depressive symptomatology and quality of life assessment among women using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: an observational study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 290(3):507–511.

- Ti A, Curtis KM. 2019. Postpartum hormonal contraception use and incidence of postpartum depression: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 24(2):109–116.

- Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Koponen P, Luoto R, Partonen T. 2012. Further evidence for lack of negative associations between hormonal contraception and mental health. Contraception. 86(5):470–480.

- Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Koponen P, Luoto R, Partonen T. 2011. Hormonal contraception and mental health: results of a population-based study. Hum Reprod. 26(11):3085–3093.

- World Health Organization. 2020. Family planning/contraception methods. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planning-contraception.

- Worly BL, Gur TL, Schaffir J. 2018. The relationship between progestin hormonal contraception and depression: a systematic review. Contraception. 97(6):478–489.

- Zeiss R, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C, Gahr M, Graf H. 2020. Depressive disorder with panic attacks after replacement of an intrauterine device containing levonorgestrel: a case report. Front Psychiatry. 11:561685.