Abstract

Research into the application of sustainable procurement in construction projects is nascent with the few prominent studies carried out in the developed nations. Of particular interest is how developing nations are rising to the challenge of development and using their procurements strategically. One way the construction industry helps to achieve sustainable development is through its procurement activities. Previous studies show that Nigeria is embracing sustainable procurement however the uptake is slow. Therefore, this research sets out to evaluate the factors that constitute barriers to sustainable procurement of publicly funded construction projects in Nigeria. A questionnaire survey was used to evaluate construction industry professionals' perspective on the barriers to sustainable procurement in Nigeria. Three hundred and twenty questionnaires were returned and used for analysis. Out of the nineteen variables tested, factor analysis reveals four clusters named in other of significance as sustainability knowledge level, transparency and governance, mismatch of procurement strategy and national policy challenges, and construction industry related factors. This study recommends that mitigating these challenges will require improving sustainability knowledge among project stakeholders, ensuring transparency and good governance, adapting procurement laws with sustainability clauses and construction industry development.

1. Introduction

Nations are using their position as volume buyers to influence the thrust of their procurement policies to encompass social and environmental dimensions (Renukappa et al. Citation2016, 19). Existing studies confirm that the construction industry plays a vital role in the adoption of sustainable procurement practices towards attaining the sustainable development goals (Rwelamila et al. Citation2000; PricewaterhouseCoopers Citation2009; Varnäs, Balfors and Faith-Ell Citation2009; Kahlenborn et al. Citation2011; Renda et al. Citation2012). However, there is paucity of empirical research on how the construction sector is addressing sustainable procurement issues (environmental, social and economic) in their whole supply chain, most especially in a developing nation's context. Studies in Nigeria have attempted to give an insight into how the public sector and the construction industry, in particular, fairs as regards sustainable procurement (Olanrewaju et al. Citation2014; Ogunsanya et al. Citation2016; Faremi et al. Citation2017). These studies conclude that sustainability adoption is low. Furthermore, Adebayo (Citation2015) contends empirically that there are inadequate policy mechanisms to embed sustainability in public procurements in Nigeria. It is therefore pertinent to unravel the causes of low uptake or lack of implementation of sustainable procurement in the construction industry seeing that the government has committed to the sustainable development agenda. The current study seeks to identify the barriers to sustainable procurement of publicly funded construction projects in Nigeria and see if the barrier factors can be further grouped into closely related components.

2. Sustainable procurement and the Nigerian construction industry

Sustainable procurement (SP) was first muted as a concept in the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002 in Johannesburg. However, the idea has its footing in the mid-1990s as green procurement (United Nations Citation2016). The initial thrust of the green procurement movement entails coupling environmental criteria into product’s requirements. This agenda has grown and widened to include social performance and new economic goals. The concept of sustainable procurement draws attention to the responsibility of a company for activities outside its boundaries (Meehan and Bryde Citation2011; Association for Project Management 2016). According to the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply (2011), it entails socially and ethically responsible purchasing, environmental impact minimization through the supply chain, and adopting economically sound solutions, all entrenched in a good business framework. It is believed that sustainable procurement saves cost and reduces waste by questioning the need to buy, reducing quantities where necessary, saving energy and water, promoting re-use and recycling, minimizing packaging and increasing transport efficiencies. Sustainable procurement actions in the United Kingdom (UK) are based on the Flexible Framework Model and the BS 8903: 2010 which entails principles and framework for procuring responsibly. Furthermore, Walker and Brammer (Citation2009) argue that the concept of sustainable procurement is consistent with the principles of sustainable development, which imply ensuring that societies develop healthily with genuine concern for human and plant life, considering environmental limits and good governance, while achieving the former through purchasing and the supply process.

Mensah and Ameyaw (Citation2012, p. 872) assert that traditional procurement entails the quest for value for money while sustainable procurement is about value for money on a whole life cycle basis considering the economic, social and environmental dimensions. Greener (Citation2008) posits that sustainable procurement is the application of sustainable development principles to procurement and this is crucial in helping to achieve a world that is habitable, affording people a good quality of life. Taking a cue from the works of Berry and McCarthy (Citation2011) and Roos (Citation2012), the four cardinal aims of sustainable procurement can be expressed as minimization of the impact of procured items (goods, services and works) across the life cycle by supply chains; reducing resource use through optimization of purchases, using resource-efficient products, re-use and recycling of products; using fair contract prices and terms while upholding utmost ethical standards, human rights protection and employment standards; and promoting equality and diversity through the supply chain (Berry and McCarthy, Citation2011; Roos Citation2012). Researchers identify the drivers of sustainable procurement are: compliance with legislation; technology and innovation; organisational structure and processes; education and training; political willingness; adoption of global strategy; knowledge of sustainable procurement; legal framework; monitoring; market demand, government policy, reputation, and customer requirements. While for the construction industry, the drivers are: value for money, reputation, market differentiation, capabilities and culture, category management and execution, structures and systems, and integration and alignment.to mention a few (Walker and Brammer, Citation2009; Belfitt et al. Citation2011; United Nations Environmental Programme, Citation2016) and Spiller, Reinecke, Ungerman and Teixeira, Citation2012).

Also, few studies have considered international variations in the engagement of public bodies with sustainable procurement. Considering the scale and importance of public procurement, and the capacity for sustainable public procurement to bring about social benefits directly and by modifying the activities of private sector organisations, it is necessary to explore how effective policy initiatives have been encouraging public organisations to purchase sustainably (McCrudden, Citation2004; Weiss and Thurbon, Citation2006).

The construction industry generally comprises of organisations and persons concerned with the process by which building and civil engineering works are procured, produced, altered, repaired, maintained and demolished. These include companies, firms and individuals working as consultants, contractors and subcontractors, material producers, equipment suppliers and builders’ merchants (Hillebrandt Citation2000; Construction Industry Development Board Citation2015). The industry works harmoniously with clients, financiers and other stakeholders. The Nigerian construction industry has as its main players construction firms ranging from the small, medium and micro enterprises to the multinational construction firms. Government is the largest client of the industry, though in recent years there is increased patronage from private sector clients (Mbamali and Okotie Citation2012). The Nigerian population continues to increase faster than the rate at which public infrastructure is provided. This infrastructure deficit has since continued. Consequently, some indigenous construction companies were established to tap into the emerging opportunities.

Furthermore, the construction sector has been a contributor to the GDP of Nigeria (Omole, 2000). This it has continued to do in a progressive manner considering the level of infrastructure need in the nation. The real GDP for the country for 2010 was N54.612 trillion. The construction sector’s contribution was N1.570 trillion. This implies a share of 2.88%. The construction sector grew by 21.30% to reach N1.905 trillion in 2011. A gradual reduction in the growth rate of the construction sector by 14.86% resulted in the sector closing at N2.188 trillion in 2012 (National Bureau of Statistics Citation2015). The sector also serves as a current and potential employer of the teaming unemployed youths in the country. The construction industry has provided over 6 million construction-related employment opportunities to both Nigerian and non-Nigerian professionals.

Despite the success of the construction sector through the Infrastructure Concession and Regulatory Commission (ICRC) reform policy, key industry players have mixed views on its wholesomeness in achieving the intended goals (ICRC Citation2012; National Planning Commission Citation2015). For instance, Ozoigbo and Chukuezi (Citation2011) and Idoro (Citation2010) argue that there are significant inequalities between economic growth and subsequent development in the Nigerian construction sector. The reform policy is viewed to confer some privileges on multinationals through outsourcing of materials and human resources with no due justifications. Critics of the practice are concerned about the implications of continued marginalisation of local skills and manufacturing sectors.

Furthermore, the clamour by stakeholders for sustainable development in Nigeria is relatively recent. The Nigerian Government took a giant step towards sustainability in 2007 when it established Nigerian Environmental Standards and Regulatory Enforcement Act (NESREA Act) and the Agency (NESREA 2007). The agency has domesticated Agenda 21 Nigeria. The principal goal was to integrate environmental dimensions into development planning at Federal, state and local government levels, to start the transition to sustainable development while addressing sectorial priorities, plans and strategies for implementation, and using the collaboration of regional and global resources. The direct implications of this is that it has become mandatory for environmental impact assessment to be undertaken before construction of public facilities, remedial measures are taken to reduce the impact of construction, and the initiation of post construction review audits (NESREA 2017). In the same year, the Public Procurement Act (PPA 2007) was passed and the Bureau of Public Procurement was established. This other agency focuses on the financial proprieties of acquisition of public goods, works and services. Ensuring value for money, accountability, transparency and respect for public thrust is maintained in transactions. Despite the aforementioned, Nigeria is lagging world developments associated with sustainability within the construction sector and beyond. There is currently no legislation requiring that a sustainable procurement policy should be applied to projects of particular magnitude and worth in Nigeria.

3. Barriers to sustainable procurement

Brammer and Walker (Citation2011) identified the barriers to sustainable procurement as financial, informational, legal, managerial/structural, political/cultural and product quality priority. Similarly, despite the advantages for the adoption of sustainable procurement at the organisational level, the following factors by Meehan and Bryde, (Citation2011) were considered critical barriers to its uptake. First is ‘inertia’ within the company. Inertia develops from the institutionalisation of a routine within an organisation. As firms try to maintain a sense of reliability, processes become routine. Thus, the implementation of changes become more difficult, as it will be an upheaval to the existing routine (Meehan and Bryde, Citation2011, Belfitt et al., Citation2011). Another is the conflict of incentives. The procurement staff could feel pressured to make decisions that do not align with sustainable procurement strategy. This could indicate that there is a conflict between the pressures on staff and the greater driving them towards maintaining, the more traditional approach. The third barrier relates to a meaningless formality. Even though many companies are documenting sustainable procurement strategies in their annual reports, it would be interesting to find out to what extent these policies influence the procurement decisions within a company. Another possible barrier is that those who are going to benefit from sustainable procurement adoption on construction projects are not the persons bearing the cost. When the cost of maintenance is considered it may seem a bit far-fetched from the contractor that builds the facility, except when build-operate-transfer or build-operate-own-transfer models are used. Likewise, some argue against the appropriateness of making the initial occupants of a building pay for end of life costs that are many years away from the initial occupants (Belfitt et al., Citation2011).

According to the Sustainable Development Commission (Citation2004), the commonly cited hindrances to sustainable procurement are: perception that it increases cost, lack of awareness of the need for sustainable procurement and the processes entailed, lack of knowledge required, risk averseness on the part of clients, legal constraints, leadership challenges and inertia. Similarly, Meehan and Bryde (Citation2011), posits that a major barrier to the adoption of sustainability in procurement is the lack of engagement with suppliers. Another barrier is the fact that some of the supply chains are multinational while the laws regulating sustainability or sustainable procurement are national or locally formulated. This dichotomy is a challenge.

Within a developing nation’s context, Mensah and Ameyaw (Citation2012: 874) argue that the following barriers must be surmounted to attain sustainable procurement in a developing nation using Ghana as a case study. These are: the absence of internal management structures that support sustainable procurement; lack of social drive from major stakeholders; low technical and management capacity; an inefficient approach to stakeholders' management; the high initial cost of green products; low stakeholders' education; the absence of government interest; lack of political will; corruption among procurement practitioners; lack of capacity for small scale suppliers and contractors (Mensah and Ameyaw, Citation2012, p. 874). The main findings of the research is that the lack of understanding of sustainable procurements and the higher initial cost associated with sustainable procurement are the most significant hindrances to sustainable procurements in Ghana. Ross (Citation2012:53) found the barriers in another developing nation’s context as legal framework that does not encourage sustainable public procurement (SPP), donor guidelines that does not encourage SPP, lack of capacity, lack of guidance materials and practical tools, complexity of SPP, expectation of increased cost, and inflexible budgetary mechanism. In Malaysia, McMurray, Islam, Siwar and Fien (Citation2013) found that religion significantly influences the decision of procurement managers in the private sector and directors in the public sectors. They identified major barriers as lack of awareness, lack of resources, lack of a long-term view to procurement decisions, lack of guidance and lack of political support when sustainable procurement practices were compared between the public and private organizations. However, Ruparathna and Hewage (Citation2015) established in a Canadian study that lack of consideration of sustainability criteria in bid evaluation topped the list when drawbacks to sustainable procurement were considered. Others are the unavailability of standard methods for procurement and lack of knowledge of local conditions. According to the United Nations (Citation2016), barriers to sustainable procurements are habit and the difficulty in changing procurement behaviour; lack of suppliers of sustainable assets, suppliers or services; complexity of comparing costing/value for money assessments; the difficulty of including factors broader than environmental considerations; and a perception that the process and outcomes are costlier or time-consuming. Although there are clear advantages for a company's adopting sustainable procurement procedures, these have not been largely realised. For instance, in the UK uptake of whole life costing in the private sector is still below 10% (Renukappa et al. Citation2016). The identified barriers from the literature above and knowledge of the Nigerian environment helped to form the critical mass of the indicator variables tested further in the study. The variables used in the study are listed is .

Table 1. Definition of potential barriers factors for sustainable procurement.

All the studies above have evaluated hindrances to sustainable procurement within different national contexts and industry sectors; it is, therefore, essential to identify the barriers to sustainable procurement of publicly funded construction projects in Nigeria. This study adopts a quantitative research approach as its methodology which is explained hereafter.

4. Methodology

This study uses a quantitative approach to identify the most critical barriers/hindrances to sustainable procurement in the Nigerian construction industry. The choice of research methodology was determined by the ontological and epistemological basis of the investigation and position of literature (Creswell, Citation2009; Bryman, Citation2012). Therefore it uses a survey method to investigate the phenomenon of interest in the study population. The survey entails administering questionnaires to willing participants carefully selected. The population of interest in this research are practitioners and professionals involved in the procurement of publicly funded construction projects in Nigeria. Simple random sampling was used to identify professionals in three major states of the country (Lagos, Ogun and the Federal Capital Territory – Abuja). The choice of the locations was due to the volume of construction projects that are publicly funded in these locations (Lagos, Abuja) while Ogun state represents an emerging business hub. Out of the 602 questionnaires that were administered which comprise personally administered questionnaires and copies sent through electronic mail, only 320 responses were useful for analysis at the close of the survey (53.2%). From the total number of respondents (N = 320), 35% (n = 111) work in Abuja, 34.1% (n = 108) work in Lagos State, 30.3% (n = 96) work in Ogun State while the remaining 0.6% work outside the main states of interest as shown in . The main survey locations critical to the study were Abuja, Lagos, and the Ogun States. Other demographic details of the respondents are indicated in . The researcher obtained the consent of the participants regarding their willingness to partake in the study and were informed it is part of ongoing doctoral research aimed at developing a sustainable procurement model for the Nigerian construction industry.

Table 2. Respondents’ demographic characteristics.

5. Data analysis

5.1. Factor analysis

According to Pallant (Citation2013:181), Factor analysis is a data reduction and analysis method. Also, Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) argue that factor analysis produces a theoretical solution untainted by unique and error variability. Thus, there are two main approaches to factor analysis (exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis). The exploratory factor analysis is used to elicit information regarding interrelationships among a set a variables while confirmatory factor analysis is used later in the research process, entailing complex and more sophisticated techniques in testing specific hypotheses relating to the structural relationships of variables. However, this study makes use of exploratory factor analysis for this paper.

5.2. Stages in exploratory factor analysis

There are 3 stages in conducting exploratory factor analysis. These are;

Assessment of suitability of data. The two prominent conditions that must be satisfied in terms of suitability of data are sample size adequacy and strength of correlation amongst the variables. Several authors hold different position as regards sample size adequacy, though there is a consensus that the larger the sample size the better. Pallant (Citation2013) holds that the size should be at least 300 cases while Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) support 150 cases. Also, on the strength of interrelationships of the variables, it is recommended that the correlation matrix should be inspected for coefficient values greater than 0.3. If larger percentage is greater than 0.3 the sample is adequate but if there are very few correlation coefficients greater 0.3 the sample is inadequate. Two tests used to confirm for the conditions above are the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

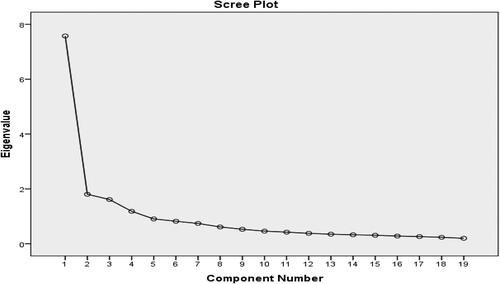

Factor extraction. This process entails identifying minimum number of factors that can be used to represent interrelationships of a set of variables. The major techniques for factor extraction are principal component, principal factors, image factoring, maximum likelihood factoring, unweighted least squares, and generalized least squares. The commonly used technique is the principal component analysis. This technique involves balancing the need for a simple solution with the minimum factors needed to explain so much variance in the original data set. The principal component analysis can be effected as Kaiser’s criterion, scree test or parallel analysis. The current study uses a scree test which is generated by plotting all the eigenvalues of the factors.

Factor rotation and interpretation. The process of rotation helps in providing clearer picture of the components generated without altering the underlying solutions. Thus, SPSS present the components as clusters of variables which the researcher uses the base theory and past researches to interpret. There are more than one technique to effect factor rotations. These are varimax, quartimax and equamax used when orthogonal rotations are desired while oblique rotations are effected by direct oblium and promax techniques. The current study used varimax technique.

5.3. Assumptions for exploratory factor analysis

Factor analysis is deemed appropriate when the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkine (KMO), the measure of sampling adequacy test index, is higher than the satisfactory minimum limit of 0.5 and a desirable limit of 0.8 or greater (Kaiser, 1970). Conventionally, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 is considered reasonably good for the scale reliability and internal consistency of the instrument (Field, Citation2009; Hair et al. Citation2010). Also, suggested a cut-off value KMO greater than or equal to 0.70. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), Bartlett’s test with a significance level of less than 0.05 substantiates the appropriateness of the factor model. The import of this is that there are potential correlations among the variables and thus indicative of a reasonable potential cluster forming factors from the variables (Field Citation2009; Hair et al. Citation2013).

Furthermore, eigenvalues greater than 1 were considered significant and were used to explain the variance obtained by a factor. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), eigenvalues of less than 1 are considered insignificant: these were excluded accordingly in the current study. Before conducting the principal component analysis, communalities extracted on each variable were assessed and presented. The communalities are critical and useful in deciding the variables that have to be finally extracted (Field Citation2009). This is because by connotation, the communalities typify the total amount an original variable shares with all other variables included in the factor analysis (Field Citation2009; Hair et al. Citation2013). According to Field (Citation2009) and Motulsky (2015), an average communality of the variables after extraction should be above 0.60 to support reliable results and interpretations in factor analysis. Also, the conventional rule about communality values in factor analysis suggests that a potentially significant variable must yield an extraction value (eigenvalues) greater than 0.50 at the initial iteration (Field Citation2009; Hair et al. Citation2013).

Factor analysis was used to establish which of the variables could be measuring the same underlying effects so that they can be grouped together. The data was screened for completeness and to ensure that missing values and incomplete data sets did not affect the analysis. As will be observed, there are more than 320 data set (i.e. >150 cases), which is sufficient for factor analysis. The analysis, findings and the discussion are as follows.

5.4. Exploratory factor analysis of barriers to sustainable procurement

Nineteen items evaluating hindrances to sustainable procurement were subjected to principal component analysis using SPSS version 22. Before this, the suitability of data for analysis was assessed. Inspection of the correlation matrix showed many of the coefficients had values of 0.3 and above. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy of 0.893 was obtained. This value is above the desirable value of 0.8. From , Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 2575.429 with an associated significance of 0.000. Also, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.913 was realized, suggesting an acceptable level of internal consistency and reliability in the measures and the scale.

Table 3. KMO and Bartlett’s test.

From , the average communality of the variables after extraction was 0.632. Hence, the communalities extracted support the use of factor analysis on the variables. It can be observed that no item had extracted eigenvalues less than the 0.50 cut-off point, hence all the variables a qualified for further analysis (Field Citation2009; Hair et al. Citation2013). Similarly, the rotated component matrix in showed four distinct components as each variable dominantly belonged to a unique factor (component). From this result, the components that emerged could be the dominant underlining factors determining barriers to sustainable procurement.

Table 4. Communalities.

Table 5. Rotated component matrix.

From the result presented in , a four-factor component solution which explained a total of 64.076% of the variance was obtained. The first component explained 39.868% of the variance; the second component explained 9.496%; while the third component 8.484%; and the last component 6.226%. The total variance explained is above the recommended minimum of 50% (Field, Citation2009; Pallant, Citation2013; Motulsky, Citation2015). The four components were named according to the factor with the highest loading in the cluster. These are explained in greater details in the discussion section. Also, the scree plot for the factor analysis is shown in .

Table 6. Total variance explained.

6. Discussion of results

6.1. Component 1 – sustainability knowledge level

The five barrier factors extracted for component 1 were Lack of awareness of sustainability concepts (80.2%), Lack of motivation for the implementation staff (77.0%), Lack of capacity in required human resources (76.8%), Reluctance of the contractor side to adopt sustainability practices in procurement (76.1%), Inadequate time for pre-contract phase (50.1%). The numbers in parenthesis are the factor loadings. This cluster accounted for 39.868% of the variance (). This cluster shares in common the general link to sustainability knowledge and awareness and capacity on the contractor side. Olanrewaju et al. (Citation2014) argue these are the bane of the Nigerian construction industry as regards sustainability. The authors claim that the awareness level of sustainable construction among industry practitioner is moderate for the majority of the survey respondents. Also, Berry and McCarthy (Citation2011) assert that there should be a sustainability agenda on every project, most especially public infrastructure that is well articulated. Thus, procurement sustainability requirements must be contractually enforceable where possible. Projects must have established standards and measurements such that non-compliance can be identified and corrected in the course of execution. If this is not done, it will be difficult for the contractors to implement sustainability in procurement. The design team must work with this mindset and specify sustainable materials (energy efficient, long-lasting, cost-effective and easily disposed at the end of life). Also, Meehan and Bryde (Citation2011) advocate genuine engagement not only with the contractor but the entire supply chain side while Adebayo (Citation2015) shows that there are inadequate policy mechanisms to embed sustainability in public procurements in Nigeria. Similarly, the perspective of Ross (Citation2012) is instructive, who contends that there is a general lack of competence in sustainability matters in developing nations. This incompetence manifests as a lack of practical tools, information and training noting that for several public entities, including environmental and social requirements into their procurement functions is a new concept. Marrakech Taskforce report shows the same deficiency and has started preliminary works in terms of pilot projects in 13 countries to foster the promotion of sustainable public procurement (UNEP 2012). The traditional position is that projects are delivered the way the client wants it. Lately, contractors have begun to offer sustainable solutions as value offerings to the client. So, request for sustainability on projects doesn't have to be at the instance of the client alone.

6.2. Component 2 – transparency and governance

The five barrier factors extracted for Component 2 were Corruption (83.3%), Political interference (70.4), Lack of enforcement of relevant laws(64.5%), Lack of monitoring and control on projects (64.1%), Lack of regulatory framework for sustainable construction procurement (55.9). This cluster accounts for 9.496% of the variance (). The numbers in parenthesis are the factor loadings. UNODC (Citation2019) claims that up to 20-25% of the procurement budget is drained through corruption globally. Eyo (Citation2017) in a review of the impact of corruption on sustainable public procurement in Africa found that at the macro level, entrenched corruption depletes the limited funds available for public spending and proposes stronger control systems at the micro/institutional levels to mitigate the actions of corrupt public officials. The reorganization of the public procurement system in Nigeria and Public Procurement Act (PPA) promulgation was to provide some of the controls that Eyo (Citation2017) suggested. Also, anti-corruption agencies such as Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and Independent Corrupt Practices and related Offences Commission (ICPC) were created to address issues arising from infractions of public procurement amongst others in Nigeria. Furthermore, when contract values are inflated to almost 4times the cost of the project, value for money on a whole life cycle basis is truncated. Also, the existing regulation (PPA 2007) is generally for goods, works and services with no direct provisions for sustainability. However, Williams-Elegbe (Citation2012) argues that the PPA falls short in international best practices on transparency by not specifying which threshold performance bond is required, giving great discretionary powers to procuring authorities regarding procurement decisions which is subject to abuse, and does not mandate procuring authorities to inform unsuccessful bidders why they lost except an official inquiry is made. At the national level, Roos (Citation2012, p. 51) contends that developing nations may need to modify their legislation to be able to incorporate sustainability criteria. Ogunsanya (Citation2018) advocates for sustainable procurement act that focuses on construction and infrastructure projects considering the share of the national budget that these constitute in Nigeria. Furthermore, Gelderman, Semeijn and Bouma, (Citation2015) argue that political leaders are less likely to promote sustainable procurement just as this study affirms.

6.3. Component 3 – mismatch of procurement strategy and national policy challenges

The 4 barrier factors extracted for Component 3 were Failure to match project needs to procurement options (80.7%), Failure of government to establish National Council for Public Procurement (76.6%), Perceived high cost of adopting sustainable solutions (69.3%), and Lack of commitment to National Development Plan (62.1%). This cluster accounts for (8.484%) of the variance (). The numbers in parenthesis are the factor loadings. At the project level, the inability of the project sponsors to identify the most appropriate procurement method to use can frustrate project sustainability (Rwelamila, Talukhaba, and Ngowi, Citation2000). Several procurement methods exist with newer ones being developed to correct some the challenges of the past (Babatunde, Opawole and Ujaddugbe, Citation2010). Also, the perceived high cost of implementing a sustainable solution is another barrier. This is taking a short term view of the sustainable procurement benefit. If a long term perspective is considered and the present-future cost/benefits are balanced sustainable procurement is cheaper on the long run. The reality is that sustainability and sustainable procurement goes beyond the environment, there are issues of health and safety of employees, appropriateness of their wages and working conditions, use of locally available substitutes among others and best value for money.

6.4. Component 4 – construction industry related

The 5 barrier factors extracted from Component 4 were Lack of confidence in local contractors (79%), Reluctance in embracing new knowledge (75.3%), Failure to adhere to quality management processes (62.2%), Non-availability of sustainable materials (62.1%) and Delays in payment of contractors (59.4%). This cluster accounts for 6.226% of the variance. For the construction industry to fully engage with sustainable procurement, there is industry readiness that is required, and the identified challenges have plagued the industry in the past. Ozoigbo and Chukuezi (Citation2011) and Idoro (Citation2010) raised questions about continual marginalisation of local skills and the manufacturing sector. Previous studies used the experiences in Singapore, Malaysia and Australia to establish that the participation of local contractors and small and medium scale suppliers are crucial to construction industry development. Further, Ofori (Citation2016) justifies how project team integration, promotion of health and safety, engagement with stakeholders, effective project governance, effective post-project reviews and the adaptation of novel ideas that have worked in other climes can positively impact on the growth of construction industry in developing nations. There is a need for development in the construction industry in Nigeria if the sector will effectively utilise and realise the benefits of sustainable procurement (Faremi et al. Citation2017). Some of the new initiatives are contractor development, contractors’ classification, construction (SMEs) empowerment through subcontracts, financial assistance to contractors with valid contracts, middle level manpower skills development, materials supply chain management, research into alternative sustainable materials, collaboration between educational institutions, professional bodies, government and financial institutions, creation of construction industry development board (Chukwudi and Tobechukwu, Citation2014; Ogunsanya, Citation2018).

7. Conclusion and recommendation

The barriers to sustainable procurement are diverse as different factors are responsible. Though the benefits of sustainable procurement in the delivery of construction projects are known. There is paucity of knowledge as to the factors that are mitigating against sustainable procurements in the Nigerian construction industry. Hence, through a survey of construction industry professionals, the barriers to sustainable procurement were classified into 4 clusters. These are; sustainability knowledge factors, transparency and governance factors, mismatch of procurement strategy and national policy issues; and construction industry development related factors. These findings lend support and align with the findings of studies in Ghana. It is therefore recommended that efforts should be intensified on awareness creation and capacity development of construction industry professionals on integrating sustainability in the procurement processes, thus leading to increase in adoption of sustainable procurement. Currently, there is no law requiring that sustainable procurement should be used to guide procurement of public assets in Nigeria. There is a need to make such a law.

Future studies should focus on how the drivers of sustainable procurement can be used to overcome these barriers. This study also provides input into requirements for developing a sustainable procurement model for the Nigerian construction industry.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants who took part in the survey and the panel of reviewers for this article in ensuring that it comes out in its best form.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adebayo VO. 2015. Exploring the impact of procurement policies, lifecycle analyses and supplier relationships on the integration of sustainable procurement in public sector organisations: A sub-Saharan African country context. Int J Sustain Energy Develop. 4(1):179–186.

- Association for Project Management 2016. Stakeholder Management. http://knowledge.apm.org.uk/bok/stakeholder-management.

- Babatunde SO, Opawole A, Ujaddugbe IC. 2010. A Review of Project Procurement Methods in Nigerian Construction Industry. Civil Eng Dimension. 12:1–7.

- Berry C, McCarthy S. 2011. Guide to sustainable procurement in construction. London: CIRIA, Classic House.

- Belfitt RJ, Sexton M, Schweber L, Handcock B. 2011. Sustainable procurement: challenges for construction practice. In: Proceedings of the Technologies for Sustainable Built Environments Engineering Doctorate Conference, 3 Jul Reading, UK. p. 1–9.

- Brammer S, Walker H. 2011. Sustainable procurement in the public sector: an international comparative study. Int J Oper Res Prod Manage. 31:451–476.

- Bryman A. 2012. Social research methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply. 2011. CIPS Sustainable procurement review, 2–3.

- Chukwudi US, Tobechukwu O. 2014. Participation of Indigenous Contractors in Nigerian Public Sector Construction Projects and their challenges in managing working capital. Int J Civil Eng Construc Estate Manage. 1(1):1–21.

- Construction Industry Development Board. 2015. Construction industry indicators. Pretoria: Construction Industry Development Board. www.cidb.org.za.

- Creswell JW. 2009. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London: SAGE Publications.

- Eyo A. 2017. Corruption and the challenge to sustainable public procurement (SPP): a perspective on Africa. European Procurement and Public Private Partnership.(3):253–263.

- Faremi O, John IB, Nwokediuko C. 2017. Sustainable building construction practice in Lagos. In: Proceedings of 13th International Postgraduate Research Conference 2017; Sept 14–17 Manchester: University of Salford, p. 870–879,.

- Field A. 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS for Windows. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications.

- Gelderman CJ, Semeijn J, Bouma F. 2015. Implementing sustainability in public procurement: The limited role of procurement managers and party-political executives. Journal of Public Procurement. 15(1):66–92.

- Greener S. 2008. Business research methods. London: Ventus Publishing ApS.

- Hair JF, Jr., Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. 2010. Multivariate data analysis. 7th edn. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice-Hall.

- Hair JF, Jr., Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. 2013. A primer on partial least squares - Structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Hillebrandt PM. 2000. The construction industry and the economy. In: Economic theory and the construction industry. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Idoro G. 2010. Influence of quality performance on client patronage of indigenous and expatriate construction contractors in Nigeria. J Civil Eng Manage. 16(1):65–73.

- Infrastructure Concession and Regulatory Commission (ICRC). 2012. Infrastructure Concession and Regulatory Commission Regulations. www.icrc.org.gov.ng.

- Kahlenborn W, Moser C, Frijdal J, Essing M. 2011. Strategic use of public procurement in Europe. Final report to the European Commission. Berlin: Adelphi, .

- Mbamali I, Okotie AJ. 2012. An assessment of threats and opportunities of globalization on building practice in Nigeria. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2(4):143–150.

- Meehan J, Bryde D. 2011. Sustainable procurement practice. Bus Strat Env. 20(2):94–106.

- Mensah S, Ameyaw C. 2012. Sustainable procurement: The challenges of practice in the Ghanaian construction industry. In: Laryea, S., Agyepong, S.A., Leiringer, R. and Hughes, W. (Eds.) Proceedings of the 4th West Africa Built Environment Research (WABER) Conference, Abuja, Nigeria, p. 871–880.

- McCrudden C. 2004. Using public procurement to achieve social outcomes. Nat Resour. Forum. 28(4):257–267.

- McMurray AJ, Islam MM, Siwar C, Fien J. 2013. Sustainable procurement in Malaysian organizations: practices, barriers and opportunities. J Purchas Supply Manage. 20(2014):195–207.

- Motulsky HJ. 2015. Common misconception about data analysis and statistics. http://www.graphpad.com/prism.

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2015. Nigerian gross domestic product report. Abuja: National Bureau of Statistics. 4(4). nigerianstat.gov.ng.

- National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Act 2007. www.nesrea.gov.ng.

- National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency 2017. Agenda 21 Nigeria, NESREA. www.nesrea.gov.ng.

- National Planning Commission. 2015. National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan (NIMP). http://www.niimp.gov.ng/?page_id=997.

- Ofori G. 2016. Construction in developing countries: current imperatives and potential in creating built environment of new opportunities. In: Proceedings of the CIB World Building Congress I, Tampere: Tampere University of Technology, p. 39–49.

- Ogunsanya OA. 2018. An integrated sustainable procurement model for the Nigerian construction industry [Unpublished Thesis], Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

- Ogunsanya OA, Aigbavboa CO, Thwala WD. 2016. Towards an integrated sustainable procurement model for Nigerian construction industry: a review of stakeholder satisfaction with current regimes. Proceeding of 9th CIDB Post Graduate Conference, Feb 2–4; Cape Town, South Africa, 2016, p. 82–91.

- Olanrewaju ALA, Anavhe PJ, Mine N. 2014. Sustainable construction procurement: A case study of Nigeria. Malaysian Construction Research Journal. 14(1):31–46.

- Ozoigbo B, Chukuezi C. 2011. The impact of multinational corporations on the Nigerian economy. European Journal of Social Sci. 19(3)

- Pallant J. 2013. SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. 4th ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Publishers.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers 2009. Collection of statistical information on green public procurement in the EU – Report on data collection results. Netherlands: PricewaterhouseCoopers. www.pwc.nl.

- Public Procurement Act 2007. www.bpp.gov.ng/?ContentPage&sub_cnt [Accessed 23 Feb 2017].

- Renda A, Pelkmans J, Egenhofer C. 2012. The Uptake of green public procurement in the EU27. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies and College of Europe.

- Renukappa S, Akintoye A, Egbu C, Suresh S. 2016. Sustainable procurement strategies for competitive advantage: an empirical study. In: Proceedings of the Inst. of Civil Engineers: Management, Procurement and Law, 169(1):17–25.

- Roos R. 2012. Sustainable public procurement: mainstreaming sustainability criteria in public procurement in developing countries. Lueneburg: Centre for Sustainability Management, Leuphana University of Lueneburg.

- Ruparathna R, Hewage K. 2015. Sustainable procurement in the Canadian construction industry: current practices, drivers and opportunities. J Cleaner Prod. 109:305–314.

- Rwelamila PD, Talukhaba AA, Ngowi AB. 2000. Project procurement systems in the attainment of sustainable construction. Sust Dev. 8(1):39–50.

- Spiller P, Reinecke N, Ungerman D, Teixeira H. 2012. The drivers of sustainable procurement performance. In: Procurement 20/20: Supply entrepreneurship in a changing world. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sustainable Development Commission 2004. Developing Sustainable procurement as a share priority –vision to reality. Final report. Sustainable Development Commission.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. 2007. Using multivariate statistics 5th ed. Boston (MA): Pearson Education.

- United Nations 2016. Sustainable development goals. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals.

- United Nations Environmental Programme 2016. Sustainable public procurement. www.unep.org/resourceefficiency/portals/24147/scp/procurement/docsres/projectInfo/studyonImpactofspp.pdf.

- United Nations 2017. UN Procurement Practitioner’s Handbook version 2017. https://www.ungm.org.

- United Nations Environmental Programme 2012. The impacts of sustainable public procurement. Rue de Milan, France: UNEP. www.unep.fr/scp/.

- UNODC 2019. Preventing corruption in public procurement to achieve the sustainable development goals. www.unodc.org.

- Varnäs A, Balfors B, Faith-Ell C. 2009. Environmental consideration in procurement of construction contracts: Current practice, problems and opportunities in green procurement in the Swedish construction industry. J Cleaner Prod. 17(13):1214–1222.

- Walker H, Brammer S. 2009. Sustainable procurement in the United Kingdom public sector. Supply Chain Management. Supp Chain Mnagmnt. 14(2):128–137.

- Weiss L, Thurbon E. 2006. The business of buying American: Public procurement as trade strategy in the USA. Rev Int Polit Econ. 13(5):701–724.

- Williams-Elegbe S. 2012. A comparative analysis of the Nigerian Public Procurement Act against international best practice. http://www.ippa.org/IPPC5/Proceedings/Part3/PAPER3-9.pdf [accessed 25 Feb 2017].