Abstract

The Construction Specification Institute (CSI) specifications are widely used to define client quality standards and facilitate communications among design and construction professionals in North America. When a US company builds a facility in China, these specifications are applied and expected to be implemented by client to ensure the project quality. Owing to differences in design and construction practices, market availabilities of products, and quality acceptance regulatory requirements, the CSI Specifications for North America must be modified to fit Chinese local regulations, market availability, and construction technology while direct translating the specification into English does not work. A CSI specification model is built based on the structure and section contents followed by the inputs of issues, research questions and category of section are developed. And 5 step analysis is provided as the solutions of localized specifications suitable for Chinese market and construction execution. Furthermore, the model is validated at a real project, followed by a discussion of evaluation and limitations. Using the code system and section content of standard CSI specification, and considering equivalent Chinese code, local market availability and quality acceptance requirements are the primary methods to localize these specifications. This approach enables defining quality expectations representing corporate brand names in a language relevant to local market stakeholders.

Introduction

In the automotive market, there are several types of vehicles that are priced over a wide range of values. The dilemma regarding selection of a particular vehicle may be solved by ‘looking at the specifications’. The manufacturer produces a set of specifications that establish the performance of the vehicle and its major components uniquely. These specifications also represent the vehicle’s corporate quality expectations.

These expectations are the same for the construction industry as well. Every company (e.g. Intel) has its own requirements that are developed from the Construction Specification Institute (CSI) specifications, and when these companies build their facilities in China, they expect adherence to their specifications in China to meet the quality requirements. Intel specifications focus on the facility performance that can meet its production environment and utility needs. Similarly, a different organization such as Disneyland may expect that its specifications focus on the façade, theme elements, and building performance.

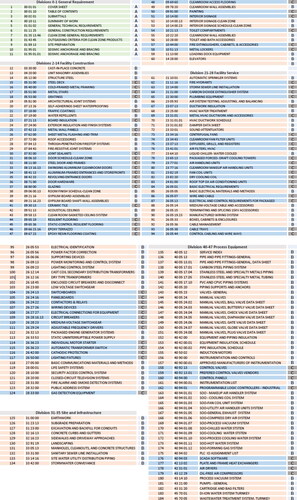

CSI Specification has 47 divisions with the overall umbrella ‘Admin’ division (Divisions 0 and 1 for general requirement and project management requirement), and four subgroups, including Facility Construction (Divisions 2 to 14, covering the basic elements of civil, structural, and architectural construction), Facility Service (Divisions 21 to 28, covering mechanical, electrical, and plumbing), Site and Infrastructure (Divisions 31 to 35, governing the connections of buildings to the boundaries of the property), and Process Equipment (Divisions 40 to 47, governing the products used for factory production). Furthermore, there is an additional hierarchic level in each subgroup governing the specific disciplines.

Each section has three parts, i.e. Part 1 General, Part 2 Products, and Part 3 Execution. Owing to the complexities of the building systems and specifications, the limited space available in this paper precludes listing all elements at this level, only major disciplines are listed to be analyzed.

In China, for the administrative management procedure, government issues various guidelines that client must comply in order to do business and obtain related permits, i.e. the construction permit. (Law of Construction, PRC Citation2011) The client has to follow the Law of Construction, tendering regulation, (Tendering Law of Construction, PRC Citation1999) and etc. to select general contractor. Also, in China, there are national codes (GB) to dictate the design, construction and quality acceptance of construction elements, such as reinforced concrete, masonry, plastering,. For the building materials and facility equipment, the client can not specify only one manufacture per the law. Since there are no specifications in China, the general requirement and description of building materials and equipment of a typical Chinese project is often identified in the design note in construction drawings as reference, or worse, simply is neglected during design, hence contractor need to handle such during construction phase.

When a US company builds a facility in China, the same CSI specifications as those required in North America are applied. However, these specifications are often new to Chinese authorities, design institutes, and construction companies, as there is currently no single standard or document that can be referred to as a set of specifications in China (Zhou Citation2018). A prevalent approach that most foreign clients take is to simply translate their countries’ CSI specifications directly into Chinese and include the translated specifications with the bid documents. This is supplemented by appropriate directions in the contract conditions which requires the contractors follow the appended specifications. The problem arises after the contractor is on board, they may have difficulties in understanding the US codes specified in the guidelines. For example, the ACI code for concrete, which should have been converted according to the corresponding Chinese code for local contractor to understand the requirements and thus the related cost. Further, the specified product might be common in North America, but may not be easily available in China. This will result in increased cost as the contractor might need to import the product from overseas (Zhang et al. Citation2020).

Without fully compliance of owner’s furnished specification, accountability and serviceability of the facility is discount which comes negative impacts over construction ecosystem (Ribeirinho et al. Citation2020). In view of the aforementioned problems and gaps, this study aim to establish a methodology to localize the specifications per Chinese conditions enable the engineers and contractor to design and build the facility per client’s quality expectations based on the specifications from North America.

Literature review

Design quality is defined as the sum of meeting the client’s expectation through the design process, providing quality design documents which meet relevant codes, social requirements, functions, purposes of the buildings, etc (Fischer and Tatum Citation1997). Scholars such as Georgy et al. (Citation2005) observed that design quality has two criteria. One is the direct quality of the design documents, and the other is the expected quality of the building itself. For cost control, the most important decisions regarding the quality of a complete facility are made during the design and planning stages rather than during construction. It is during these preliminary stages that component configurations, material specifications, and functional performance are decided.

Current study demonstrate the functions and significance of the specifications. It is widely acknowledged that the expected quality of a project is typically codified in specifications, such as those produced by the CSI, and referenced by design and constructions documents. Furthermore, standards from the CSI specifications are intended to serve as an important communication tool for all stakeholders. CSI (Citation2020) noted, successful professionals rely on CSI standards to improve communication with their teams and deliver exceptional results to their customers. Therefore, in this study the CSI coding system is retained so that the North American professionals are able to refer to the appropriate sections when working with Chinese professionals. CSI (2020) states that, ‘Design professionals rely on CSI standards…to produce buildings that are safe, up-to-code and long-lasting’. This statement suggests that the standards provide a tool that designers can use to define building quality.

On top of the functions of specification, some research also combine the specifications into construction management process and management plat form. Hou et al. (Citation2020) pointed out connecting the traditional off-site contractor to innovative technological paradigms and collaborators including architects, engineers, building professionals and property managers, where the specification plays an important role to communicate. Abbas Ali et al. (Citation2018) integrated two currently applied philosophies in construction management, i.e. project management and lean construction, where better and cheaper building equipment and materials shall be used. Sarkar et al. (Citation2020) provided an effective and real time platform enable latest building equipment and materials can be available and specified.

More research already did study to localize the CSI specification. Hwang and Zhao (Citation2015) emphasized the importance of specifications that define the quality of a building facility. Hou et al. (Citation2020) also noted the importance of specifications required by the client. However, a few engineers and contractors in China believe that such specifications are related only to manufacturing requirements (Zhou Citation2018). Accordingly, some studies have compared these specifications with construction product standards such as the JG/T151-2015 (Zhang Citation2019). Other studies have analyzed and reported the structure of the CSI specifications, explained its 49 divisions, and described Parts 1, 2, and 3 in Chinese terms (Zhang et al. Citation2020). These studies have focussed on translating the relevant specification documents into Chinese without referring extant Chinese codes and standards. Accordingly, these reported studies have not provided an integrated solution to help Chinese designers and contractors understand the essentials of the specifications.

In practice, the translated specifications were not fully usable owing to the reasons listed in , thereby lowering the quality standards by contractors for the client is often expected. A solution to localize the CSI specifications is currently lacking hence development of such is of upmost necessary. A localized CSI specification model will enable the local stakeholders to understand, specify, design, and construct facilities according to client requirements and meet the client quality expectations in terms of the built facilities.

Table 1. Issues with specifications in China.

Methodology

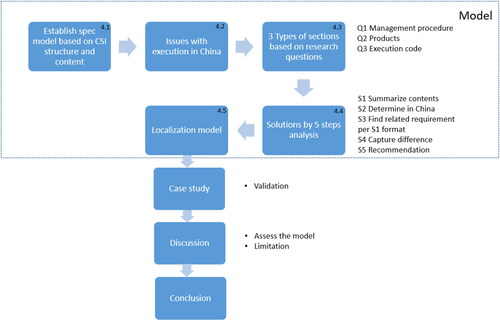

This study builds a specification model first based on the CSI specification structure and section contents with capture of major contributions. The method design is exhibited in . The model is further developed by adding (1) execution issues, (2) research questions, and (3) typical sections. These three elements are appropriate drawing on our consultation experience. By using 5 steps analysis method to conclude the solutions to form the final localization model. Further, the model is validated in the case study where Project A emerged to be a good project for validation purpose. Firstly, Project A is invested by a foreign investor with their own CSI specifications. Secondly, the authors had provided extensive consultation service to Project A where workshops are conducted, and quantitative data are collected. We tested our localized model in Sample Sections. The performance of localized model is validated through the extent to which cost are reduced. This is an encouraging result. This is followed by a discussion for the application and limitations.

CSI specification localization model

CSI specification model

Per the methodology presented, the model is established per the CSI specification structure and section contents per . A completed CSI structure will be presented and categorized into three typical sections, where five steps of comparison will be conducted to categorize the results into three methods that will be regressed into the CSI structure to obtain the CSI specification localization methodology matrix.

Table 2. CSI specification model.

Issues with specification execution in China

By input the issues of execution in China, based on the research questions, we categorize the typical sections into A, B and C per . To be more specific,

Table 3. CSI specification model version 1 with execution issues in china, research questions and typical sections.

Type A: Div. 0 and Div. 1, project management procedure and requirement.

Type B: Divs. 03, 04, 05, and 31, cast in-suit work.

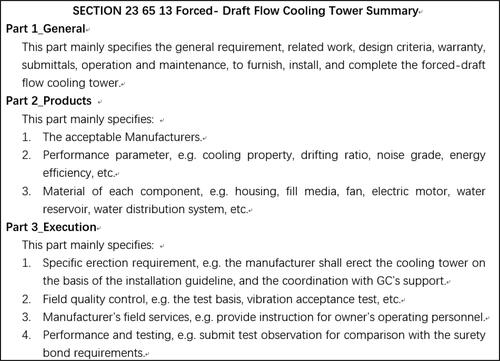

Type C: Other divisions such as mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and process.

Type A addresses management issues, client requirements, management procedures, deliverables, etc. Type B is the ‘cast in-suit’ work where the design codes from both countries are different; in China, there are national codes that specify the workmanship, procedure, tolerance, etc. Since the raw materials will be mixed, and the Chinese codes have a requirement that these materials are available in the local market, we may consider using local materials and local labour. Type C section involves mainly installation work for architecture, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing requirements, and local materials equivalent to the US product shall be sourced and specified, with the installation compliant with the Chinese codes.

Three typical sections per research questions

Based on the above analysis, we categorize the data into three models to evaluate the differences between the standards followed by the two countries and their market conditions, as shown in .

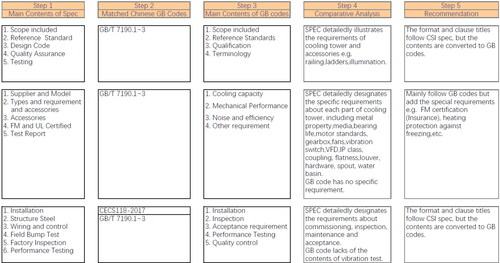

Five steps of typical model section comparisons

Once the typical model section is identified, detailed comparisons are conducted to align the differences and close the gaps.

Step 1: Summarize the components of the specification to provide a starting point for localization.

Step 2: Determine the relevant regulations in China.

Step 3: Summarize step 2 as per the step 1 format.

Step 4: Compare step 3 to step 1 and capture the differences.

Step 5: Provide recommendations for localization.

For each typical model, detailed comparisons will be conducted. The three typical section positions and the corresponding CSI structures are shown in .

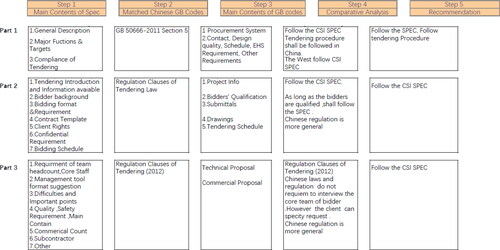

Type a section comparison for a typical CSI specification

Section 00 11 19 ‘Request for proposal’ comparison represents a typical type A CSI specification. A detailed comparison is presented in .

Type B section comparison for a typical CSI specification

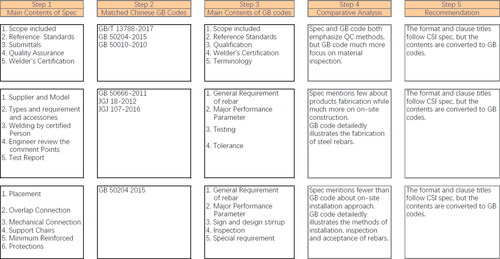

Section 03 21 11 ‘Plain steel reinforcement bars’ comparison represents a typical type B CSI Specification model. The detailed comparison is presented in .

CSI specification localization model

To regress the three typical model section solution methods into the CSI Model, a finalized CSI specification localization Model is developed as per ‘CSI Specification Localization Model’.

Table 4. CSI specification localization model.

Case study

Due to the confidentiality agreements we had with the client, this case study project is referred to as ‘Project A’. The authors had provided extensive consultation service to Project A where workshops are conducted, and data are collected. The Project A is an assembly and testing facility constructed for a US client in Chengdu, China. The preliminary concept was provided by the client’s US team using a form called the Owner Design Requirement (ODR). The client expected that the design would be executed in compliance with both Chinese compulsory code (GB Code) and US code requirements, including the International Fire Code (IFC), International Building Code (IBC), National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), FM Global, and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certifications. The client had some previous experience with smaller size projects in China and therefore understood the challenge of executing such international construction project in China with international-level quality requirements, including the use of the CSI specifications.

Localized specification section list

The US client and design team conducted a two-day workshop to select the appropriate sections of the CSI specifications. The adapted code structure is shown in . The design team further examined the elements of the building to be designed and listed the specifications that were to be defined and localized based on the methodology shown in .

Sample sections

Three typical types of localized specifications are demonstrated as reference for the readers.

Type A

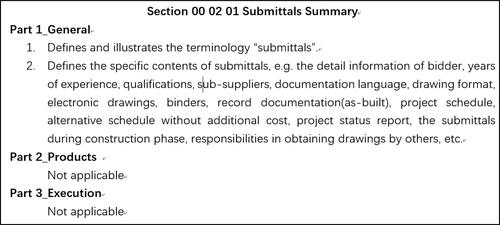

For the Division 0 and Division 1, all sections followed the CSI format and a few sentences were changed to meet the local requirements.

The localized 00 02 01 ‘Submittals’ summary is given in ‘Section 00 02 01 Submittals Summary’.

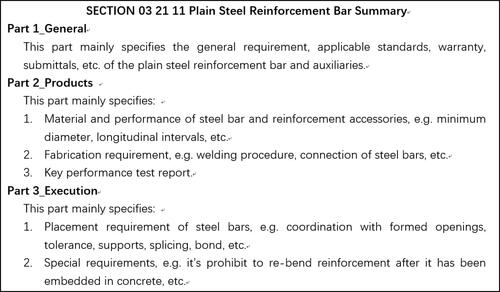

Type B

The entire team invested time and effort to study the codes from both countries. By specifying the local raw materials and construction codes, localized specifications were executed. The sample Section 03 21 11 Plain steel reinforcement bars summary is given in ‘Section 03 21 11 Plain Steel Reinforcement Bar Summary’.

?>Cost comparison

shows the claims from the specifications from previous project without properly localized vs the claim at this project. From the production stakeholders who are final users of the facility also satisfied the delivered facility.

Table 5. Cost comparison for project using CSI specification and localization CSI specification in China.

Discussion

As noted previously, each company has its own specification representing its corporate brand name and quality requirements. Customized specifications are based on and developed from the CSI specifications. This process is not illustrated in this work; instead, the comparison and localization from CSI specifications, which has wider scope, has been investigated.

The CSI specifications have more than 30,000 sections, and to categorize them into three typical sections may be impractical which will fail to consider unique scenarios. However, by categorization, we can simplify the study and establish a methodology to localize the specifications in a more systematical way.

In China, a cast in-suit product, such as concrete or masonry wall, has its own design and construction codes that must be followed. The final quality does not vary if the workers follow the expected codes. To draft the specifications needed, engineers who know the codes and regulations from both countries are required.

However, for facility services, such as HVAC, utility and electrical system, the performance may depend on the facility equipment, such as chillers and AHU. The current Chinese law does not allow the engineer to single source the products in the interest of avoiding conflicts. However, the engineer is allowed to specify and use the term ‘or Equivalent’. The JG151-2015 Classifying and Coding of Construction Product standard introduces the CSI coding structure to the Chinese market. Although coding is good for structural reference, the details of the specifications need to be written on a case-by-case basis.

The Select Technologies of Building Product 2009 catalog is widely used among engineers in China to select construction materials and equipment for projects. Similar to the JG151-2015, this catalog enables finding the product, but the format of performance and installation are not specified. Therefore, such catalogs can serve as starting points, but the engineers need to do conduct more market analyses.

Academically, the current literature rarely investigates the contributions and functions of specifications. This is evident in our desktop research where only limited research is identified that specify the equipment products or major construction materials. This paper attempted to bridge the gap by proposing an approach to localize specifications based on the CSI specifications structure and sections combining regulations, codes, and markets in China.

Conclusion

The CSI specifications establish the facility quality expectations and present the corporate brand name imaging requirements for North American clients; it also serves as a communication tool among construction professionals and can be utilized by designers to define the ‘expected’ building quality. Localizing the CSI specifications relative to Chinese practices, regulations, and codes can align the quality expectations and execution for both markets and thereby enable construction of facilities that meet the quality standards of both markets. To localize the CSI specifications to the Chinese standards while still retaining their clarity and intent, the original structure and coding system must be retained. For Division 0 and Division 1, project management and administration, some modifications were necessary. For the Civil Work and Structure Work divisions in the Facility Construction subgroup, the Chinese GB codes were retained, as was the case for the Site and Infrastructure Work divisions. For the remaining sections, the mechanical, electrical, plumbing, outfit and process, and product availability should be checked and specified. This process helps to resolve all four questions raised in .

Note that in China, a designer cannot specify the manufacturer or product by name. Normally, clients are able to overcome this limitation by demonstrating a must-need ‘production’ requirement or process related function. However, an approach to address the legal implications of such limitations when working with a localized code remains to be investigated. Furthermore, even if the designer is able to specify a certain product or piece of equipment, the method for selecting these from thousands of potential manufacturers might present challenges that must be overcome. These limitations are expected to be addressed in a future study.

Data availability statement

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abbas Ali SA, Arun C, Krishnamurthy K. 2018. Re-defining flow in construction process for facilitating the identification and quantification of generic overruns existing in construction industry today. Int J Constr Manage. 21:113–130. DOI: 10.1080/15623599.2018.1511236.

- CSI (Construction Specifications Institute). 2020. Overview. [accessed 2020 Dec]. http://www.csiresources.org/standards/overview.

- Fischer M, Tatum CB. 1997. Characteristics of design – relevant constructability knowledge. J Constr Eng Manag. 123(3):253–260.

- Georgy ME, Chang LM, Zhang L. 2005. Utility-function model for engineering performance assessment. J Constr Eng Manage. 131(5):558–568.

- Hou L, Tan Y, Luo W, Xu S, Mao C, Moon S. 2020. Towards a more extensive application of off-site construction: a technological review. Int J Constr Manag. DOI: 10.1080/15623599.2020.1768463.

- Hwang B-G, Zhao H. 2015. Review of global performance measurement and benchmarking initiatives. Int J Constr Manag. 15(4):265–275.

- Law of Construction, PRC. 2011. https://www.renrendoc.com/paper/119193396.html.

- Ribeirinho MJ, Mischke J, Strube G, Sjödin E, Blanco JL, Palter R, Biörck J, Rockhill D, Andersson T. 2020. The next normal in construction - How disruption is reshaping the world's largest ecosystem. McKinsey & Company. www.mckinsey.com.

- Sarkar D, Patel H, Dave B. 2020. Development of integrated cloud-based Internet of Things (IoT) platform for asset management of elevated metro rail projects. Int J Constr Manage.

- Tendering Law of Construction, PRC. 1999. https://wenku.baidu.com/view/a09c6c284b35eefdc8d3335e.html.

- Zhang L, Hu H, Zhang S. 2020. INT-3343 claim aspects in China. In Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering (AACE) 2020 Conference & Expo. Chicago: AACE.

- Zhang X. 2019. 建筑设计标准化的实现路径探讨——基于建筑产品技术规格书应用. [Discussion on the realization path of architectural design standardization – Based on the application of technical specification of construction products]. Construction Economy of China, Vol. 040, No. 009, p. 109-114. ISSN: 1002-851X. [In Chinese]

- Zhou J. 2018. Executive design management of theme parks. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.