?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the impact of job satisfaction on the organizational commitment of women quantity surveyors (WQS) in the South African construction industry. This investigation was done to promote female participation within the construction industry by establishing significant job satisfaction factors that organizations can improve upon. A post-positivism philosophical approach, using a questionnaire survey, was employed to obtain quantitative data from registered WQS. The data obtained were analyzed using frequencies, percentages, mean item scores, Kruskal–Wallis H-test, and partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Using the organization commitment scale developed in past studies, it was found that WQS in the study area exhibited more continuance commitment. Also, their job satisfaction level is below average. PLS-SEM revealed that the continuance commitment exhibited is negatively influenced by the job satisfaction variables. The findings of this study provide valuable benefits to employers of construction organizations as the creation and enhancement of supportive work practises, structures, and cultures can help to attract and retain female quantity surveyors in the construction sector.

Introduction

The quantity surveying profession has been described as one that requires a high level of professional competence rooted in genuine ethical conduct (Murdoch and Hughes Citation2008). This submission was made on the assertion that the quantity surveyors (QS) as cost managers are a cynosure of all eyes on a project (Oke et al. Citation2017). The importance of the quantity surveying profession to the construction industry has been reiterated in past studies (Olatunji et al. Citation2014; Samarasinghe and Lanka Citation2016). However, in describing the profession, Bowen et al. (Citation2008) and Paul et al. (Citation2021) noted that there is a shortage of women quantity surveyors (WQS) due to the male-dominated nature of the profession. Therefore, to get the optimum productivity from the few available WQS that will positively impact the overall delivery of construction projects, it is important to ascertain the job satisfaction of this set of professionals. Also, understanding how this job satisfaction influences the type of commitment exhibited by these WQS is essential.

Job satisfaction has been described as the pleasure or sense of accomplishment an employee derives from their job (Onukwube Citation2012). This satisfaction is driven by an organization’s effective support and favourable policies to help employees carry out their job functions effectively (Sergeant and Frenkel Citation2000). The concept of job satisfaction is universal, with multiple measurement features. It has continued to garner attention in various industries and countries worldwide as a result of its relationship with key organizational and employee issues such as the performance of workers, absenteeism, turnover, organizational productivity and the job commitment of workers (Onukwube Citation2012). On the other hand, organizational commitment is how workers identify with their organization. This can be attributed to the workers’ belief in and acceptance of the goals and ethics of their organization as well as the intention to remain in and contribute positively to the attainment of the set goals of their organization (Zeinabadi Citation2010). A previous study has shown a trichotomy of organizational commitment (Mathur‐Helm Citation2005). These are continuance, affective and normative commitment types (Oyewobi et al. Citation2012). An individual’s preference to stay with their current organization may stem from an emotional bond (affective commitment), a need for economic security or the high cost of switching employers (continuance commitment), or a sense of moral obligation (normative commitment) (Dockel et al. Citation2006).

According to Jahn (Citation2009), women head some of the most successful organizations in the construction industry in South Africa. However, Martin and Barnard (Citation2013) stated that the progress toward gender equality in corporate places in South Africa remains dismal. Moreso, the number of female construction workers in the country is still low compared to their male counterparts, with many more leaving the industry due to unfavourable working conditions. This low participation is also evident in the quantity surveying profession, where in 2020/2021 alone, the number of male registrations almost doubled that of females both at the candidate and professional levels (South African Council of the Quantity Surveying Profession, Citation2021). In light of this problem, it is important to understand the job satisfaction of the available WQS and assess how this job satisfaction impacts their job commitment. This is quintessential as not many studies in developing countries (South Africa inclusive) have empirically explored how job satisfaction among female construction professionals impacts organizational commitment. Moreover, past study has noted some linear relationship between the job satisfaction of workers and their organizational commitment (Kreitner and Kinicki Citation2011). To this end, this study strives to unearth the job satisfaction of WQS within the South African construction industry using Gauteng as the area of focus. The study also examined the impact of this job satisfaction on the different commitment types exhibited by these set of professionals. The study’s outcome is expected to promote female participation within the quantity surveying profession and the construction industry by establishing significant job satisfaction factors that organizations can improve upon. The study also provides recommendations on how construction companies may establish an atmosphere that will satisfy female employees while on the job. This, in turn, will influence the performance of these sets of workers and their commitment to their organization.

Improving organizational commitment and job satisfaction of women quantity surveyors

In recent times, studies on gender balance have continued to emanate within the construction industry. Focus has been placed on the need for more women within the construction industry to ensure the availability of adequate skills, diversity in skills and knowledge, as well as long-lasting progress within the industry (Amaratunga et al. Citation2007; English and Hay Citation2015; Le Jeune Citation2009). Like other professions, there is a shortage of female quantity surveyors when compared to their male counterparts due to several factors (Bowen et al. Citation2008; Paul et al. Citation2021). In Australia, Northey (Citation2023) submitted that while women account for half of the workforce, they only represent 16% of the quantity surveying profession in the country. As of 2019, female quantity surveyors in the United Kingdom represent 9% of the registered quantity surveyors (Bowes Citation2020). The situation is no different in South Africa, where the number of registered male quantity surveyors is almost double that of females (South African Council of the Quantity Surveying Profession, 2021). Evidently, ensuring the few available WQS are satisfied with their job and committed to staying within their organizations is essential to the current call for gender balance in the construction industry. Van Eck (Citation2016) have earlier noted that little research had been done on the job satisfaction of quantity surveyors. As such, in improving the job satisfaction and organization commitment of WQS, drawing from extant studies that have concentrated on the construction industry as a whole becomes reasonable.

Studies have shown a relationship between employee motivation, job satisfaction, and the number of people who leave their jobs. Motivated employees tend to be happier with their jobs, which reduces staff turnover and, in the long run, makes an organization more successful (Kreitner and Kinicki Citation2011). Dainty and Lingard (Citation2006) noted that the lack of supportive work practises, structures and cultures make it hard for women (WQS inclusive) to get into and stay in the construction industry. It was noted that women in professions that men dominate often work in environments and conditions that are not specific to their capacity and needs because of gender bias in the organizational cultures (Le Jeune Citation2009). There are not many supportive organizational practices for these women to use, and organizations often leave them to figure out how to adapt to the industry on their own. Nevertheless, organizations may make it simpler for women to remain in the construction sector if they enhance the working circumstances of women, particularly on building sites and provide them with both physical assistance and policies that are designed with women in mind (Martin and Barnard Citation2013). This is essential, particularly for WQS, who supervise site works or are expected to often be onsite to carry out their duties.

The research by Martin and Barnard (Citation2013) revealed that mentoring and immediate supervision is important and helpful ways for women to stay in industries that are dominated by men. According to Hinson et al. (Citation2006), a survey conducted indicated women all agreed that mentoring roles should be improved to cater for women in the workplace. Most of the people who participated in the research study said they needed female mentors and supervisors. Mentors and supervisors will give directions, help with work problems, and deal with their work-life balance and emotional issues (Chovwen Citation2004). Based on the findings of a study conducted on Malaysian construction companies by Jaafar et al. (Citation2014), WQS leave their jobs because of a bad work environment, stressful supervisors, careless co-workers, and other work-related problems. Jaafar et al. (Citation2014) further opined that WQS would rather work under the direction of a not just brilliant but also informed and courteous supervisor. Additionally, they like to collaborate with co-workers that are accountable, ambitious, and supportive.

Chovwen (Citation2007) submitted that women reported in a survey that family-work conflict, among other things, was a big reason why they could not move up in their careers in male-dominated executive industries. Cha (Citation2013) also pointed out that men’s family responsibilities are not as affected by their increased work responsibilities as women. In the study by Martin and Barnard (Citation2013), it was found that some women had amazing career success stories that made them want to keep working in male-dominated fields. These accomplishments that women talk about were what kept them going and gave them the confidence to know that sticking with their jobs wasn’t a waste of time. Oyewobi et al. (Citation2012) noted that career development and recognition also improve employees’ job satisfaction. This is because it was found that employees are happier with their jobs when they are given adequate recognition. Based on this, companies need to have policies that appreciate, recognize, and encourage their WQSs when they do a good job.

Dimitriou (Citation2012) submitted that job satisfaction can be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic satisfaction comes from factors such as opportunities for personal growth, the job itself, and the feeling of doing a great job. On the other hand, extrinsic satisfaction comes from being happy with salary. Workers may stay with an organization if it makes it hard for them to quit and pays them to stay. Jahn (Citation2009) noted that when a fair salary structure is made for women with adequate recognition, they would be encouraged and inspired to work in the South African construction industry. Also, Amaratunga et al. (Citation2007) opined that, though advancement and promotion are always linked, research shows that women have fewer opportunities to grow on the job than men do. According to Dimitrio (Citation2012), women are more likely to work in back-office jobs like personnel, human resource management, and communications than in front-office jobs like production. So, most of the time, they do not have enough work experience to get promoted. Employees are more loyal to their company when they know the company’s promotion policy. This is because it makes them less uncertain about their career future with that company. Promotion opportunities and policies can also influence commitment. The decision about who gets the promotion could affect how committed those who did not get the promotion are to their jobs. This means that organizations should be clear with those who did not get the promotion about how they made their decisions.

Research methodology

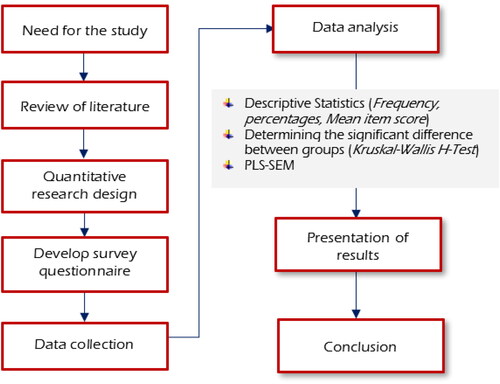

The study adopted a post-positivism philosophical approach which informed the use of a deductive reasoning and a questionnaire to gather quantitative data. gives an overview of the research methodology adopted. The study population was WQS registered with the South African Council of Quantity Surveying Profession (SACQSP) and practising in Gauteng province. The choice of conducting the study in Gauteng was premised on the notion that the province has the highest number of construction output, organizations and professionals compared to other provinces in the country (CIDB, Citation2020). According to the Council of the Quantity Surveying Profession 2018 report, Gauteng province has 1,263 candidates and professional WQS. Using the Yamane’s 1967 sample size formula, this target population was reduced to 304 at a level of precision of 5% (95% confidence interval). An electronic questionnaire designed in sections was adopted for the study.

The questionnaire included a cover letter inviting the respondents to participate voluntarily in the survey and describing the nature of the study. In addition, the respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality throughout the survey. As such, no information that could lead to the identity of the respondents was asked. The first section of the questionnaire assessed the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Section two sought answers to the level of job satisfaction of the WQS on a five-point scale. The respondents were presented with eight satisfaction variables derived from the review of literature and were asked to rate them based on their level of satisfaction, with five being ‘very satisfied’ and one being ‘very dissatisfied’. The third section was designed to assess the type of commitment exhibited by the WQS. Meyer et al. (Citation1993)’s organizational commitment scale (OCS) was adapted for this third section and the impact of the variables on the commitment of the respondents was assessed on a five-point Likert scale with five being ‘very large extent’ and one being ‘no extent at all’. This OCS scale has been adopted in past organizational commitment studies in the construction industry (Abiola-Falemu Citation2013; Aghimien et al. Citation2019; Jena Citation2015). Using random sampling, a total of 185 questionnaires were retrieved out of the 304 distributed. This represented a response rate of 61% and was considered adequate for further analysis and for drawing logical conclusions.

The analysis of the data gathered on the demographic characteristics of the respondents was done using frequency and percentage. Mean item score () was employed to rank the level of satisfaction and influence of the commitment variables as rated by the respondents. Kruskal-Wallis H-test (K-W) was also used to test the disparity in the rating of the different variables by WQS from contracting, consulting and government organizations. The K-W test gives a p-value which must be less than 0.05 for a significant difference to exist in the rating of the different groups of respondents. The hypothesis was further assessed using Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) in SmartPLS 3.0. PLS-SEM is a second-generation multivariate analysis that employs the ordinary least squares regression-based approach as an estimation method for explaining total variance in a dataset (Gefen et al. Citation2000). This analysis is suitable for determining cause-effect relationships (Hedaya and Saad Citation2017), as in the case of this current study. PLS-SEM has continued to gain significant attention in construction-related studies because it accommodates the non-normality that is associated with most questionnaire data, and it also caters for small samples (Hair et al. Citation2019; Henseler et al. Citation2016; Wong Citation2013).

Result and discussion

Demographic characteristics

The analysis of the demographic characteristics of the respondents revealed that 72% of the respondents are single, while 21% are married. The remaining 7% are either divorced or living with their partners. The respondents’ average age was 29 years, with an overall four years of working in their current organization. In terms of their years of working experience as a QS, the result revealed that 58% have up to 5 years, while the remaining 42% have above five years in the profession. Most of these respondents (80%) have a bachelor’s degree, with 11.4%, 8.1% and 0.5% possessing a diploma, master’s and doctorate degree. In addition, 45.4% work in consulting firms, while 38.9% and 15.7% work in contracting and government organizations. The demographic characteristics of the respondents for this study show that responses were gathered from WQS with a vast wealth of experience in the profession and with a good academic background to understand the questions posed in the research.

Job satisfaction and commitment of women quantity surveyors

The result in gives the job satisfaction variables as rated by the different groups of respondents. The result shows consistency in the rating of nature of work (SAT7) and co-workers’ relationship (SAT6) as the two major areas wherein WQS in contracting, consulting and government organizations are satisfied. These two variables gave values of 3.49 and 3.45 respectively. The K-W test confirms the consistency in these ratings as a p-value of above 0.05 was derived for both variables. In addition, while the work-life balance (SAT5) is the least area of satisfaction for WQS in contracting organizations, promotion opportunity (SAT1) is the worse for those in consulting organizations. WQS in government organizations are less satisfied with appreciation and recognition for good work (SAT3). Overall, these WQS are less satisfied with promotion opportunities (SAT1,

= 2.52) and work-life balance (SAT5,

= 2.46). More so, the group

gave a low

of 2.94 value showing that WQS are generally not satisfied in terms of the assessed satisfaction variables.

Table 1. Job satisfaction of WQS.

The result in shows the type of commitment exhibited by WQS in the South African construction industry. For affective commitment, overall, the result revealed that the motivation to do a better job (AFF7, = 3.46), a feeling of acceptance and inclusion in the organization (AFF4,

= 3.45), and holding the same beliefs and principles as the organization (AFF8,

= 3.40) were the top-ranked commitment variables. K-W test revealed some disparity in the rating of the eight variables in this group, with four having a significant p-value of less than 0.05.

Table 2. Organizational commitment of WQS.

For continuance commitment, the result revealed the concern that one might not develop (CON3), concern at one’s lack of progress (CON4, = 3.70), lack of job opportunities that are currently accessible in the industry (CON9,

= 3.66) and the concern that one’s talents are not being utilized fully (CON2,

= 3.52) are the top-ranked continuance commitment features by the three groups of respondents. The K-W test revealed no significant difference in the rating of nine out of these ten variables by the different groups as a p-value of above 0.05 was derived. However, there is a significant difference in the rating of difficulty to resign, when necessary (CON5), which gave a p-value of 0.048.

For normative commitment, the overall rating showed that out of the six assessed variables for this commitment type, only the employee’s dedication to their current organization (NOM2) had a that is above average of 3.11. The low rating of these variables shows that most WQS rarely exhibit normative commitment. This is evident in the group

which gave a value of 2.77. The K-W test shows a significant difference in the rating of ‘feeling of remorse if I were to accept a better job offer from somewhere else and then quit my current position’ (NOM4) as a p-value of 0.046 was derived. However, there is a convergence in the rating of the remaining five variables as a p-value of above 0.05 was derived.

Looking at the group for each of the commitment types, it is evident that continuance commitment is the most exhibited type with a group

of 3.44. This is followed by affective commitment with a group

of 3.29 and the least being normative commitment with a group

of 2.77.

Impact of job satisfaction on job commitment of women quantity surveyors

Reflective measurement model assessment

In understanding the impact of job satisfaction on the type of commitment exhibited by WQS, PLS-SEM was conducted. First, the reflective measurement model, also known as the outer model, was assessed based on indicator reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity, discriminant validity and multicollinearity. The indicator reliability was assessed through the factor loadings with a cut-off of 0.7 sets for acceptable indicators (Gotz et al. 2012). The result in revealed that some variables had factor loading below the set cut-off. As a result, these variables were eliminated to improve the overall model reliability and fitness (Hulland Citation1999). The final iteration shows that a total of eleven variables were eliminated, and the retained variables had a good indicator reliability of above 0.7, thus implying that they explain more than 50% of their variance (Hair et al. Citation2019). The internal consistency of each group in the model was also tested using the combination of Cronbach alpha (α), Rho coefficient (ρA) and composite reliability (ρc) as suggested in past studies (Hair et al. Citation2019; Wong Citation2013). The acceptable cut-off for the α and ρA tests is 0.7 and above (Hair et al. Citation2019). For ρc, a value range of 0.7 to 0.9 is considered good, while values of 0.95 and above are deemed problematic (Diamantopoulos et al. Citation2012) The result of the final iteration in revealed that all the groups in the model met these set cut-offs and as such the reflective model is deemed to have good internal consistency.

Table 3. Summary of the reflective measurement model assessment.

The average variance extracted (AVE), which tells the extent to which the convergence of the construct in explaining the variance of its items (Hair et al. Citation2019; Henseler et al. Citation2016; Wong Citation2013), was used to test the convergent validity of the reflective measurement model. The cut-off for this test is 0.5 (Hair et al. Citation2019; Henseler et al. Citation2016). The result from the final iteration also showed that the assessed measurement variables have a good convergent validity with an AVE of above 0.05. In addition, no multicollinearity was evident in these retained measurement variables, as the variance inflation factor (VIF) revealed values less than the set cut-off of 5.0 (Hair et al. Citation2019).

Lastly, the discriminant validity, which is the extent of empirical distinction of a construct from others in the model (Hair et al. Citation2019), was tested using the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio. An HTMT value of lower than one must be achieved for clear discriminant validity. Preferably a value of 0.85 and below (Franke and Sarstedt, 2019). shows that all the groups assessed met this set cut-off, and as such, they can be considered distinct from one another.

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

Structural model assessment

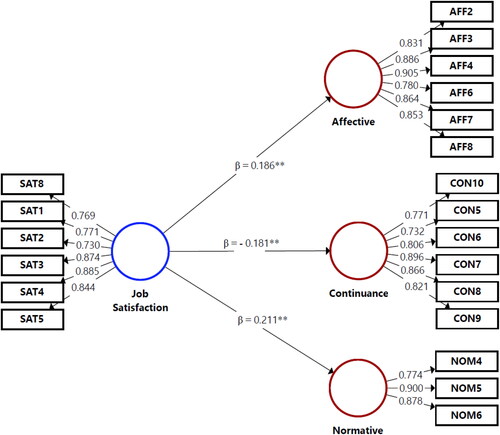

The result in and shows the structural relationship between the job satisfaction of WQS and the commitment types exhibited. This analysis used the bootstrapping approach with 4999 samples, as Henseler et al. (Citation2016) recommended. It has been noted that in cases where the researcher intends to generalize from a sample to a population (like in the case of this current study), the path coefficient (β) must be examined (Henseler et al. 2019). The significance of the β is based on the t-value derived, which should be at least 1.96 for a 95% confidence interval (p-value < 0.05) (Wu et al. Citation2019).

Table 5. Structural relationship.

The result revealed that the retained job satisfaction variables, i.e. promotion opportunities (SAT1), immediate supervision (SAT2), appreciation and recognition for good work (SAT3), remuneration (SAT4), work-life balance (SAT5), and managerial responsibilities (SAT8), all have a positive significant impact on the affective commitment being exhibited by some of these WQS. These satisfaction variables account for 18.6% (β = 0.186) impact on the attainment of affective commitment. Also, these retained job satisfaction variables have a significant impact on the continuance commitment being exhibited by some of these WQS. However, this impact is negative as a β value of −0.181 was derived. As such, if the satisfaction level increases for the retained six satisfaction variables, the exhibition of continuance commitment among these workers will decrease and probably move towards a more desired affective commitment. Lastly, a significant p-value of 0.002 was derived for the relationship between the retained satisfaction variables and the normative commitment. These satisfaction variables exact a 21% (β = 0.211) impact on this commitment type.

Unlike other types of SEM, PLS-SEM does not require several models fit analyses. However, the use of standardized root means square residual (SRMR) and Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (NFI) has been suggested (Byrne, 2008; Henseler et al. Citation2016). The ideal cut-off for SRMR is 0.08 (Henseler et al. Citation2014), and NFI range between 0.6 to 0.9 (Singh Citation2009). The analysis in this study revealed an SRMR of 0.066 and an NFI of 0.796. These values were within the thresholds, so the derived model was considered fit for adoption.

Discussion and implication of findings

The findings show that the job satisfaction of WQS in the study is below average and, as such, need significant improvement. From the perspective of the organizational types, the result revealed that while WQS working within contracting firms are less satisfied with their work-life balance, those working in consulting firms desire more promotion opportunities, and those in government organizations need more appreciation and recognition for the job they do. Dlamini et al. (Citation2019) and Shehata and El-Gohary (Citation2011) have earlier noted that the construction industry is project-based, and most contractors expect their workers to be able to travel to deliver projects in different areas and, in most cases, put in extra-long hours. This invariably impacts the work-life balance of these workers, including the WQS employed in these organizations. As such, to ensure that their WQS have a work-life balance, these organizations need to put in place measures such as leave, health and wellness programmes, and work flexibility among others, as suggested by Aghimien et al. (Citation2022). In the same vein, management within consulting firms and government organizations will be better off by improving the opportunities for the promotion of WQS and ensuring that their effort is given due recognition, as this is vital to the job satisfaction of these workers.

The findings further show that the retained job satisfaction variables have a significant positive impact on affective commitment. Affective commitment refers to the emotional attachment, identification, and positive feelings that individuals have towards their organization or profession. These findings highlight the importance of addressing and enhancing job satisfaction among WQS, as it can positively influence their affective commitment. By improving the factors contributing to job satisfaction, organizations and professionals in the field can potentially foster stronger emotional connections and organizational commitment among WQS. This result is consistent with the findings of Saeed et al. (Citation2013), who highlighted the essential role of job satisfaction in improving the attitude of employees to perform their jobs more effectively and efficiently as they are motivated to execute their activities. This finding may be further explained by the fact that employees who are motivated tend to feel accepted and are more likely to make sacrifices for their employers as well as stick with the goals and objectives of the organization (Sohail and Ilyas Citation2018). Therefore, employers are often interested in understanding the factors that influence employees’ job satisfaction because it also influences their organizational performance, as observed by Muwardi et al. (Citation2020). Moreover, the findings further extend that of Jaafar et al. (Citation2014), who emphasized the emotional connection felt by employees with their construction industry positions when they are fully invested in it. In their submission, aside from being able to execute their tasks better, employees who are satisfied with their jobs have a higher tendency to develop admiration and gratitude for the organization. An emergent implication of this finding is the need for employers of construction organizations to develop structures and cultures that would help to increase affective commitment among WQS.

Also, the retained job satisfaction variables possess a significant impact on continuance commitment. The finding suggests that when WQS experience higher levels of job satisfaction, it reduces their perceived costs or sacrifices associated with leaving their organization or profession. This implies that job satisfaction plays a crucial role in shaping individuals’ commitment by influencing their perceptions of the benefits and drawbacks associated with staying or leaving. By creating an environment that supports job satisfaction, organizations can reduce the perceived barriers to leaving and increase the perceived benefits of staying. This can result in a more committed workforce and contribute to the overall stability and success of WQS. The negative path coefficient (β -value) observed in this study aligns with previous submissions by Markovits (Citation2012) and Kasogela (Citation2019), highlighting the need to pay close attention to the retained six satisfaction variables. As such, an increase in the satisfaction level of these variables will decrease the exhibition of continuance commitment among employees and probably tend towards a more desired affective commitment. This implies that employers of construction organizations must make conscientious efforts to appreciate their employees by recognizing good efforts in executing tasks, ensuring a work-life balance, and providing them with constructive feedback as appropriate. This approach will raise their morale and motivate them to deliver better ideas (Lian and Ling Citation2018). More so, with the implementation of incentivization pathways, employees will be inspired to exhibit more dedication and commitment, thus, improving their affective commitment to the organization (Jahn Citation2009).

Furthermore, the retained job satisfaction variables also significantly impact normative commitment. The finding suggests that when WQS experience higher levels of job satisfaction, it increases their sense of obligation to their organization. This indicates that job satisfaction not only influences the emotional attachment and positive feelings (affective commitment) but also contributes to a stronger sense of duty and moral obligation (normative commitment) towards their work. By creating a work environment that fosters job satisfaction, organizations can help cultivate a sense of ethical responsibility among their workforces. This result also aligns with the findings of Luz et al. (Citation2018), who posit that employees who experience job satisfaction are often morally obliged to stay with the organization regardless of the sense of accomplishment they receive. Meyer and Parfyonova (Citation2010) asserted that employees who possess this commitment type feel they have an ethical responsibility to stick with the organization. This often stems from an emotional bond an employee has with the organization. An emergent implication is that employers must design ways to foster a healthy work environment by building a strong teamwork culture. According to González and Guillén (Citation2008), an organization that promotes team building will develop employees who are motivated to work and achieve more, thus, boosting their commitment levels and creating long-term workforce harmony. Furthermore, organizations that breed an aura of transparency will improve the confidence of their employees as they feel valued and part of the bigger picture of the organization (Luz et al. Citation2018).

These findings highlight the interconnectedness between job satisfaction and different dimensions of commitment. By recognizing and addressing the job satisfaction variables that influence affective, continuance and normative commitments, organizations and professionals can work towards creating an environment that not only promotes positive emotions and attachment but also fosters a strong sense of duty and moral obligation among WQS. These insights contribute to the understanding of the complex relationship between job satisfaction and commitment, emphasizing the need for organizations to consider and prioritize factors that enhance job satisfaction to promote a more committed and dedicated workforce among WQSs.

Conclusion and recommendations

Based on the findings, the study concludes that job satisfaction of WQS in the study area is below average, and they exhibit more continuance commitment to their organizations. Furthermore, job satisfaction variables such as promotion opportunities, immediate supervision, appreciation and recognition for good work, remuneration, work-life balance, and managerial responsibilities significantly impact the three commitment types (affective, continuance and normative). Therefore, to maintain job satisfaction WQS, construction organizations must be ready to create supportive work practises, structures, and cultures to help attract and retain these sets of professionals in the industry. One good approach is to eradicate the stereotypes attached to the construction sector, which has often been branded as a male-dominated profession. This obsolete perception of the construction sector has understandably dissuaded women from studying construction-relevant subjects and ultimately deterred them from seeking industry-related jobs and in most cases, discouraged the few who have secured employment. It is worth noting that the construction industry’s activities, processes and operations are experiencing an unprecedented revolution due to the emergence of innovative tools, which has transformed the sector from being manually intensive to a more digitally driven sector. As construction organizations invest in technologies, women are presented with smarter and automated approaches to executing industry tasks which can go a long way in enhancing the working circumstances of not just female construction workers but also the construction workforce in general. Also, construction organizations can create a supportive culture for women by enforcing zero-tolerance harassment policies, implementing fair salary structures and creating ample opportunities for the advancement of their careers, such as supporting their quest to upskill and reinvent themselves.

Furthermore, construction organizations must be ready to regularly conduct workshops and seminars to train employees on implicit bias and misogyny. This will help to eradicate unfavourable working conditions for women. Moreso, older women in the industry must be retained to act as role models and mentors to younger women who are still trying to carve out their career paths. This, in turn, will influence how effectively the female employees perform their duties and how dedicated they will be to the organization. While attracting female quantity surveyors into the construction industry is essential, keeping them satisfied with their jobs is just as, if not more important. Practically, the findings obtained from this study will benefit construction firms in South Africa and other developing countries as it provides recommendations on how construction companies may ensure the happiness of female employees while they are on the job. By investigating the levels of contentment and dedication felt by women in construction, industry employers can improve on existing measures to improve job satisfaction among women. By deploying some of the recommendations mentioned in this study, women will most likely exhibit high levels of affective and normative commitment and decreased exhibition of continuance commitment. Theoretically, this study contributes to the broader ever-growing discussions on how women can be retained in the construction sector due to their caring nature, creativity, empathy, listening skills, openness, trust, interpersonal understanding, and willingness to help.

Despite the valuable contributions of this study to the existing body of knowledge, some limitations exist. This study was conducted in the Gauteng province of South Africa; therefore, its findings may not be generalized to other parts of the country. As such, to gain a broader perspective of the subject matter, future research studies could be conducted in other provinces across South Africa. Also, the quantitative nature of this research prevented respondents from suggesting other satisfaction variables they may deem necessary. This methodological limitation can be addressed in future studies by employing a more pragmatic approach, such as combining quantitative and qualitative methods to guard against any weaknesses that may exist by virtue of using the quantitative method as a standalone approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- Abiola-Falemu JO. 2013. Organizational culture, job satisfaction and commitment of Lagos-based construction workers. IOSR J Business Manage. 13(6):108–120.

- Aghimien D, Aigbavboa CO, Thwala WD, Chileshe N, Dlamini BJ. 2022. Help, I am not coping with my job! – A work-life balance strategy for the Eswatini construction industry. ECAM. ahead-of-print doi:10.1108/ECAM-11-2021-1060.

- Aghimien DO, Awodele OA, Maipompo CS. 2019. Organisational Commitment of Construction Skilled Workers in Selected Construction Firms in Nigeria. JCBM. 3(1):8–17. doi:10.15641/jcbm.3.1.481.

- Amaratunga D, Haigh R, Shanmugam M, Elvitigala G. 2007. Construction and women. In Cape Town, Proceedings of the 17th CIB World Building Congress Conference, 14-17 May 2007, Cape Town International Convention Centre, p. 3233–3247.

- Bowen P, Cattell K, Distiller G, Edwards PJ. 2008. Job satisfaction of South African quantity surveyors: an empirical study. Construct Manage Econ. 26(7):765–780. doi:10.1080/01446190801998724.

- Bowes D. 2020. An Aspirations-led Capabilities Approach to Women’s Career Pathways in Quantity Surveying United Kingdom. A PhD Thesis submitted to the University of Westminster,

- Cha Y. 2013. Overwork and the Persistence of Gender Segregation in Occupations. Gender Soc. 27(2):158–184. doi:10.1177/0891243212470510.

- Chovwen CO. 2007. Barriers to acceptance, satisfaction and career growth: implications for career development and retention of women in selected male occupations in Nigeria. Women Manage Rev. 22(1):68–78. doi:10.1108/09649420710726238.

- Chovwen CO. 2004. Mentoring and women’s perceived professional growth. IFE Psychol Int J. 12(1):126–132. doi:10.4314/ifep.v12i1.23513.

- Construction Industry Development Board. 2020. Construction monitor – transformation, Q4 [accessed 2020 December 22]. http://www.cidb.org.za/publications/Documents/Construction%20Monitor,%20Transformation%202020.pdf.

- Dainty ARJ, Lingard H. 2006. Indirect discrimination in construction organizations and the impact on women’s careers. J Manage Eng. 22(3):108–118. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2006)22:3(108).

- Diamantopoulos A, Sarstedt M, Fuchs C, Wilczynski P, Kaiser S. 2012. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. J Acad Mark Sci. 40(3):434–449. doi:10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3.

- Dimitriou CK. 2012. The impact of hotel business ethics on employee job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention. A Doctoral dissertation submitted to the Graduate Lubbock, United States: Faculty of Texas Tech University.

- Dlamini B, Oshodi OS, Aigbavboa C, Thwala A. 2019. Work-life balance practices in the construction industry of Swaziland. Proceedings of 11th Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) Postgraduate Research Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 28-30th July.

- Dockel A, Basson JS, Coetzee M. 2006. The effect of retention factors on organizational commitment: an investigation of high technology employees. SA J Hum Resour Manag. 4(2):20–28. doi:10.4102/sajhrm.v4i2.91.

- English J, Hay P. 2015. Black South African women in construction: cues for success. J Eng Des Technol. 13(1):144–164. doi:10.1108/JEDT-06-2013-0043.

- Gefen D, Straub D, Drexel University. 2000. The Relative Importance of Perceived Ease of Use in IS Adoption: a Study of E-Commerce Adoption. JAIS. 1(1):1–30. doi:10.17705/1jais.00008.

- González TF, Guillén M. 2008. Organizational commitment: a proposal for a wider ethical conceptualization of normative commitment. J Bus Ethics. 78(3):401–414. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9333-9.

- Gotz O, Liehr-Gobbers K, Krafft M. 2010. Evaluation of structural equation models using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares, V. E. Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang, Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Handbooks of Computational Statistics, p. 47–82.

- Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. 2019. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. EBR. 31(1):2–24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203.

- Hedaya AMA, Saad SMA. 2017. Causes and effects of cost overrun on construction project in Bahrain: part 2 (PLS-SEM path modelling). Mod Appl Sci. 11(7):28–37.

- Henseler J, Dijkstra TK, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Diamantopoulos A, Straub DW, Ketchen DJ, Jr, Hair JF, Hult GTM, Calantone RJ. 2014. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: comments on Rönkkö & Evermann 2013. Organizational Res Methods. 17(2):182–209. doi:10.1177/1094428114526928.

- Henseler J, Hubona GS, Ray PA. 2016. Using PLS path modelling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind Manage Data Syst. 116(1):2–20. doi:10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382.

- Hinson R, Otieku J, Amidu M. 2006. An exploratory study of women in Ghana’s accountancy profession. Gen Behav. 4(1):589–609. doi:10.4314/gab.v4i1.23347.

- Hulland J. 1999. Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strat Mgmt J. 20(2):195–204. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::AID-SMJ13>3.0.CO;2-7.

- Jaafar M, Puteri Yazrin MY, Nuruddin AR, Jalali A. 2014. How women quantity surveyors perceive job satisfaction and turnover intention. Int J Business Technopreneurship. 4(1):1–19.

- Jahn M. 2009. Discrimination against women in the construction, and industry in South Africa Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. An unpublished Degree thesis submitted to the Department of Quantity Surveying,

- Jena RK. 2015. An assessment of demographic factors affecting organizational commitment among shift workers in India. Management. 20(1):59–77.

- Kasogela OK. 2019. The impacts of continuance commitment to job performance: a theoretical model for employees in developing economies like Tanzania. Adv J Social Sci. 5(1):93–100. doi:10.21467/ajss.5.1.93-100.

- Kreitner R, Kinicki A. 2011. Organizational Behavior. McGraw-Hill education; New York, USA.

- Le Jeune K. 2009. Entry and career barriers applied to the South African construction sector: a study of the perceptions held by female-built environment management students. In Proceedings TG59 People in Construction, 12-14 July 2009, Port Elizabeth, p.147–159.

- Lian JK, Ling FY. 2018. The influence of personal characteristics on quantity surveyors’ job satisfaction. BEPAM. 8(2):183–193. doi:10.1108/BEPAM-12-2017-0117.

- Luz CMDR, de Paula SL, de Oliveira LMB. 2018. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and their possible influences on intent to turnover. REGE. 25(1):84–101. doi:10.1108/REGE-12-2017-008.

- Markovits Y. 2012. The two 'faces’ of continuance commitment: the moderating role of job satisfaction on the continuance commitment organizational citizenship behaviour relationship. Int J Acad Organ Behav Manag. 3:62–82.

- Martin P, Barnard A. 2013. The experience of women in male-dominated occupations: a constructivist grounded theory inquiry. SA J Ind Psychol. 39(2):01–12. doi:10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1099.

- Mathur‐Helm B. 2005. Equal opportunity and affirmative action for South African women: a benefit or barrier? Women Manage Rev. 20(1):56–71. doi:10.1108/09649420510579577.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. 1993. Commitment to organisations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol. 78(4):538–551. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538.

- Meyer JP, Parfyonova NM. 2010. Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 20(4):283–294. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.09.001.

- Murdoch J, Hughes G. 2008. Construction Contracts Law and Management. London: Spon.

- Muwardi D, Saide S, Indrajit RE, Iqbal M, Astuti ES, Herzavina H. 2020. Intangible resources and institution performance: the concern of intellectual capital, employee performance, job satisfaction, and its impact on organization performance. Int J Innov Mgt. 24(05):2150009. doi:10.1142/S1363919621500092.

- Northey J. 2023. IWD 2023: encouraging the next generation of women into tech industry. IT Brief Australia. Available at: https://itbrief.com.au/story/iwd-2023-encouraging-the-next-generation-of-women-into-the-tech-industry#:∼:text=While%20women%20make%20up%2051, that%20percentage%20is%20even%20less. [accessed 10 June, 2023]

- Oke AE, Aghimien DO, Aigbavboa CO. 2017. Effect of code of ethics on quantity surveying practices in Ondo State, Nigeria. In Ibrahim Y., Gambo, N., Katun, I. Procs of the 3rd research conference of the Nigerian Institute of Quantity Surveyors, held between 25th – 27th of September, Abubakar Tafawa Belewa University, Bauchi, Nigeria, p. 144–155.

- Olatunji SO, Oke AE, Owoeye LC. 2014. Factors affecting performance of construction professionals in Nigeria. Int J Eng Adv Technol. 3(6):76–84.

- Onukwube HN. 2012. Correlates of job satisfaction amongst quantity surveyors in consulting firms in Lagos, Nigeria. CEB. 12(2):54. doi:10.5130/AJCEB.v12i2.2460.

- Oyewobi LO, Suleiman B, Muhammad-Jamil A. 2012. Job satisfaction and job commitment: A study of quantity surveyors in Nigerian public service. IJBM. 7(5):179–192. doi:10.5539/ijbm.v7n5p179.

- Paul CA, Aghimien DO, Ibrahim AD, Ibrahim YM. 2021. Measures for curbing unethical practices among construction industry professionals: quantity surveyors’ Perspective. CEB. 21(2):1–17. doi:10.5130/AJCEB.v21i2.7134.

- Saeed R, Lodhi RN, Khan MZ, Ahmad W, Dustgeer F, Sami A, Mahmood Z, Ahmad M. 2013. Factors Affecting the Job Satisfaction of Employees in Banking Sector of Pakistan, A Generalization from District Sahiwal. World Appl Sci J. 26(10):1304–1309.

- Samarasinghe SJ, Lanka S. 2016. Factors affecting job satisfaction of quantity surveyors in Sri Lankan construction industry. Int J Eng Manage Res. 9(3):176–196.

- Sergeant A, Frenkel S. 2000. When do customers contact employees satisfy customers? J Serv Res. 3(1):18–34. doi:10.1177/109467050031002.

- Shehata ME, El-Gohary KM. 2011. Towards improving construction labour productivity and projects’ performance. Alexandria Eng J. 50(4):321–330. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2012.02.001.

- Singh R. 2009. Does my structural model represent the real phenomenon? A review of the appropriate use of structural equation modelling model fit indices. Mark Rev. 9(3):199–212. doi:10.1362/146934709X467767.

- Sohail M, Ilyas M. 2018. The impact of job satisfaction on aspects of organizational commitment (affective, continuance and normative commitment). J Manage Sci. 12(3):221–234.

- South African Council of the Quantity Surveying Profession. (2021.). Annual Report – 1 April 2020 to 31 March, 2021. Available at: https://static.pmg.org.za/SAQSP_AR_2021-AnnualReport-Final-asat30Sept.pdf. [accessed 31-01-2023]

- Van Eck E. 2016. Human capital in quantity surveying practices: Job satisfaction of generation Y quantity surveyors University of Pretoria. (Doctoral dissertation).

- Wong KK. 2013. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark Bull. 1(Technical Note):1–32.

- Wu Z, Jiang W, Cai Y, Wang H, Li S. 2019. What hinders the development of green building? An investigation of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16(17):1–18.

- Zeinabadi H. 2010. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as antecedents of organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) of teachers. Proced - Social Behav Sci. 5:998–1003. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.225.