ABSTRACT

E-mail is having a profound impact on the workplace; this is particularly true for schools and for those in the position of principal. This article uses data from interviews with 70 school principals to illustrate how e-mail influences their work and workload. Benefits of e-mail use for principals include convenient and efficient communication with stakeholders, the opportunity to better manage workloads, and the ability to document daily communications by creating an accountability trail. Challenges include high volumes of e-mail, extended workdays, increased workload, greater expectations of shorter response time, and a blurring of the boundaries between work and home. The most compelling finding is that e-mail communication has intensified contemporary principals’ work and transformed the principalship into a mobile position with poorly defined work hours.

The Internet, e-mail, smartphones, and social networking have profoundly impacted the work environments of a number of professions. The education sector, specifically the school principalship, has been highly affected (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000; Anderson & Dexter, Citation2005; Cho, Citation2016; Cho & Jimerson, 2016; Davies, Citation2010; Fullan, Citation2014; Gurr, Citation2000, Citation2004; Schiller, Citation2003; Sheninger, Citation2014; Yee, Citation2000). Many scholars have purported that technology makes work easier, increases efficiency, reduces paperwork, and promotes work–life balance (Fullan, Citation2014; Sheninger, Citation2014). The emerging evidence that describes how school principals manage the changes resulting from increased use of e-mail in the workplace is not uniformly positive, however. For example, because principals are increasingly expected to engage with and respond to e-mail messages, they may suffer from the same lack of work–life balance experienced by other “connected” professionals (Duxbury, Higgins, Smart, & Stevenson, Citation2014; Towers, Duxbury, & Thomas, Citation2006).

This article explores e-mail as a factor influencing principals’ work. First, we begin by discussing the concepts of work and work intensification. Second, we describe the ways school technology leadership and an increased reliance on e-mail have influenced the work of principals. Third, we describe the framework and methodology we used to conduct this study. In the fourth section, we discuss our findings: We review the benefits and highlight the challenges of e-mail in principals’ work. We conclude by discussing how e-mail use contributes to contemporary principals’ work intensification.

The concept of work

In its broadest sense, principals’ work includes all of the practices, actions, tasks, and activities that impact the operation of their school(s) (Fineman, Citation2003, Citation2012); this work is influenced by jurisdictional policies and initiatives (Leithwood & Azah, Citation2014; Pollock, Wang, & Hauseman, Citation2015; Spillane, Citation2015), as well as the social customs and traditions associated with the principalship and schooling. For the purposes of this study, work can occur at any time during the day (Applebaum, Citation1992; Fineman, Citation2012), and involves the leadership actions principals conduct at their school(s), their home offices, and events or meetings that occur away from the school—essentially, any place principals respond to work e-mail messages.

Work intensification

There is emerging evidence that work intensification is an increasingly common challenge that contemporary principals face (Bottery, Citation2016; Miller, Citation2016; Niesche, Citation2011; Pollock et al., Citation2015; Starr, Citation2012; Starr & White, Citation2008). Williamson and Myhill (Citation2008) have indicated that work intensification is a general trend in workplaces across the developed world, and that “the education sector is not immune or protected” (p. 25). Work intensification involves a simultaneous increase in both the volume of one’s workload and the complexity of the tasks, duties, activities, and actions that comprise one’s work (Alberta Teachers’ Association, Citation2012; Allan, O’Donnell, & Peetz, Citation1999; Green, Citation2004; Pollock et al., Citation2015). Specifically addressing the education sector, Galton and MacBeath (Citation2002) described work intensification as the “increasing pressure to do more in less time, to be responsive to a greater range of demands from external sources, to meet a greater range of targets, to be driven by deadlines” (p. 13). Some scholars have also argued that a key component of work intensification, at least in a K–12 education context, involves a loss of control over one’s work situation (Alberta Teachers’ Association, Citation2012; Ballet & Kelchtermans, Citation2009; Galton & MacBeath, Citation2002).

Impact of work intensification on principals

Work intensification has been linked to a variety of negative outcomes for employees, including low levels of job satisfaction, as well as mental health and wellness concerns (Fournier, Montreuil, Brun, Bilodeau, & Villa, Citation2011; Franke, Citation2015; Green, Citation2004; Yu, Citation2014). This finding also applies to some principals. For example, in a large-scale survey of Ontario’s principal population, 29% of the sample reported engaging in potentially unhealthy behaviors to cope with the stress and demands of their roles (Pollock et al., Citation2015). As work intensification is a relatively new phenomenon, these negative consequences may be a product of employees having little experience coping with new job demands (Franke, Citation2015). Further, these negative consequences can be compounded with employers’ lack of experience supporting employees dealing with work changes as a result of intensification.

Factors intensifying principals’ work

Principals’ work intensification is influenced by a number of different factors. In addition to increased reliance on information and communication technology (ICT) and e-mail, these factors include market-based pressures such as international comparisons or student outcomes, increased levels of student diversity, accountability policies and mechanisms, and the implementation and ongoing management of a number of initiatives (DiPaola & Tschannen-Moran, Citation2003; Galton & MacBeath, Citation2002; Gurr, Citation2000, Citation2004; Leithwood, Citation2001; Leithwood, Steinbach, & Jantzi, Citation2002; Pollock & Hauseman, Citation2015; Pollock et al., Citation2015; Shields, Citation2010; Volante, 2012; Williamson & Myhill, Citation2008; Ryan, Citation2006).

ICT as a factor intensifying principals’ work

While the several different factors listed above are at least partially responsible for the intensification of principals’ and other educators’ work, other evidence hints that ICT, such as e-mail, enables the amplification and escalation of intensification pressures (Alberta Teachers’ Association, Citation2012; Ballet & Kelchtermans, Citation2009; Galton & MacBeath, Citation2002; Hvidston, Hvidston, Range, & Harbour, Citation2013; Williamson & Myhill, Citation2008). For example, the Alberta Teachers’ Association found that technology “speeds up the pace of work, exacerbates work intensification, and blurs the boundaries between work and home life” (Alberta Teachers’ Association, Citation2012, p. 17). Further, while ICT may allow principals to engage in work practices more efficiently, it has also introduced new mandatory practices, such as e-mail. (Gurr, Citation2000). E-mail—specifically as a leadership/management tool—is not the only form of ICT that has intensified principals’ workload, however. The introduction of ICT to education as a teaching and learning aid has also added to principals’ work. Some scholars refer to this approach as school technology leadership.

School technology leadership

Until recently, e-mail was mainly confined to traditional working hours, as computers and mobile phones were too expensive for personal use and too heavy to transport to and from the workplace (Towers et al., Citation2006). Over the past 20 years, however, the “technological chains that once bound office workers to their desks have been broken” (Towers et al., Citation2006, p. 594). These innovations have significantly impacted principals, whose school districts have encouraged them to become technology leaders at their schools (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000; Anderson & Dexter, Citation2005; Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003; Gurr, Citation2004; Yee, Citation2000).

To act as school technology leaders, principals engage in a number of different practices (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000; Anderson & Dexter, Citation2005; Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003; Yee, Citation2000)—for example, they allocate, and support spending on, technology resources (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000; Anderson & Dexter, Citation2005; Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003; Yee, Citation2000). If principals act as school technology leaders, their shared visions will include technology use in their schools (Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003; Yee, Citation2000). Moreover, they will model technology use by using e-mail and other forms of technology (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000; Anderson & Dexter, Citation2005) and ensuring access to meaningful professional learning so all staff can effectively integrate technology in their classrooms (Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003; Yee, Citation2000). Finally, principals who practice school technology leadership seek to build partnerships and network to further their schools’ vision or goals (Anderson & Dexter, Citation2000, Citation2005; Flanagan & Jacobsen, Citation2003).

Although these additional practices contribute to principals’ work intensification, we are particularly interested in how principals model technology use with e-mail and other forms of technology. Modeling e-mail use can increase the sheer volume of e-mail messages that principals send and receive—but volume is not the only issue. It is the prominence of e-mail use in delegating, discussing, and sharing and gathering information that eventually creates an environment where, as Haughey (Citation2006) argued, talk becomes text.

Haughey (Citation2006) first signaled the impact of computers and ICT on principals’ work a decade ago. Her study found that ICT increases the use of distributed leadership for those who possess the skills to use it effectively. However, she also noted that employing distributed leadership could be connected to work intensification—as their workload increases, principals are forced to delegate tasks to others. She determined that administrative talk has become text: Connected principals communicate more often using e-mail rather than traditional methods such as face-to-face meetings, which allows principals to be more efficient and engage with a broader range of stakeholders (Haughey, Citation2006). Other research has focused on the specific role e-mail has played in principals’ work, and is outlined below.

E-mail and principals’ work

E-mail has long been a preferred form of communication for principals (Gurr, Citation2000, Citation2004); however, it appears that the volume of e-mail that principals receive has increased over the past two decades. Ontario principals recently reported spending an average of 11.5 hours per week sending and receiving e-mail, with many indicating they receive over 100 e-mail messages a day—numbers that dwarf those reported more than a decade ago (Pollock, Citation2014). Scholars have also found that e-mail has increased the volume of communication/information that principals both send and receive (Hines, Edmonson, & Moore, Citation2008). This heavy use of e-mail starkly contrasts earlier findings reported in the early 2000s, when e-mail was still largely a work-based phenomenon. For example, in 2003, only 51.6% of Australian principals reported receiving more than 20 e-mail messages per week (Schiller, Citation2003). Further, Anderson and Dexter (Citation2000 Citation2005) found that principals rarely used e-mail to communicate with multiple groups of stakeholders. Finally, principals interviewed by Gurr (Citation2000) did not feel the need to check their e-mail on a daily basis.

The increase of e-mail volume also extends principals’ workdays. The advent and proliferation of e-mail and relatively inexpensive computers, smartphones, tablets, and remote connections used to access e-mail, have provided employers and employees with the ability and opportunity to extend time spent “on the clock” (Duxbury et al., Citation2014; Gurr, Citation2000; Towers et al., Citation2006). As a result of this process, employers expect employees to be on call at all times, willing and able to respond promptly to any inquiry (Duxbury et al., Citation2014; Towers et al., Citation2006). For instance, in a recent survey of 33,000 Canadian professional office workers, 70% of the sample felt the advancements of e-mail in their workplace made achieving work–life balance more difficult, and led to increased stress and work intensification (Duxbury et al., Citation2014; Towers et al., Citation2006). Not only does this evidence point to the role of e-mail in work intensification, but also highlights its tendency to erode the boundary between home and the workplace.

Principals may also experience a learning curve when navigating new e-mail applications and programs. Evidence has shown that many principals are entering the latter stages of their careers and can hardly be considered “digital natives” (Brockmeier, Sermon, & Hope, Citation2005; Gurr, Citation2000; Schiller, Citation2003; Sheninger, Citation2014). Scholars have also described the professional development opportunities for principals interested in improving their technological skills and abilities as limited and varied (Brockmeier et al., Citation2005; Sheninger, Citation2014). However, it does appear that principals are making use of ICT platforms such as Twitter to engage in their own self-directed professional learning (Cho, Citation2016; Cho & Jimerson, Citation2017; Sauers & Richardson, 2016). Twitter is an online social networking service where users communicate with one another using messages that are 140 characters in length (Cho, Citation2016; Cho & Jimerson, Citation2017; Sauers & Richardson, 2016). Twitter is a convenient communication tool that principals can use to connect with colleagues and engage in professional learning (Cho, Citation2016).

Engaging in professional development opportunities on Twitter, such as Twitter chat sessions, can make principals feel more knowledgeable about educational issues and buffer professional isolation by providing them with a sense of belonging (Cho, Citation2016; Cho & Jimerson, Citation2017). However, recent studies have found that few principals can describe how engaging in professional development opportunities have influenced their practice (Cho, Citation2016). Further, the public nature of Twitter can be problematic for principals, as they may be reluctant to engage in the types of candid conversations and meaningful discussions needed for significant professional learning to take place (Cho & Jimerson, 2016). E-mail is a much more private form of communication: Principals can send messages to an individual or a small group of recipients.

Methodology

This article aims to illustrate how e-mail influences the nature of principals’ work. Specifically, we focus on the experiences and understandings of principals who currently work in Ontario English-speaking public and Catholic school systems. We first describe the sampling procedures used to generate the sample, and the sample itself. Second, we discuss the semi-structured interviews used to collect the data. We conclude the methodology section with an account of the process used to analyze the interview data.

Sampling

During the participant-recruitment phase of this study, our goal was to obtain a diverse sample that broadly represented the different educational contexts in Ontario. We used purposive sampling to generate the sample for this study (Gall, Gall, & Borg, Citation2005; Merriam, Citation2009; Robson & McCartan, Citation2016). In each of the participating school districts, we sought to interview both male and female principals working in elementary and secondary schools, as well principals employed in urban, suburban, and rural contexts. Our study also sought to include insight from both experienced principals with more than five years in the role, as well as novice principals with fewer than five years of experience. Using these criteria, we asked supervisory officers in seven school districts to provide the names and contact information of principals they thought would be willing to participate and who could provide valuable insight into the impact of e-mail on their workload.

Description of the sample

Our sample was comprised of 70 principals from seven different school districts in Southwest Ontario. Of those interviewed, only 18 principals were relatively new to the role, while 52 had at least five years of experience. There was a similar disparity in the types of school where we sampled principals’ work, and in the population density of the areas surrounding the schools. Only 18 participants worked in secondary schools; the remaining 52 principals worked in the elementary panel. Fifty-two participants also worked in schools located in areas considered to be urban or suburban, while only 18 of the principals who were interviewed worked in rural settings. In terms of gender, 28 of the 70 interviewed principals self-identified as male, with the remaining 48 self-identifying as female.

Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews with the 70 school principals between June 2012 and April 2013. We asked the participating principals how their work was influenced by labor relations, changing student demographics, ICT, existing and emerging managerial roles and responsibilities, instructional leadership practices, and accountability systems. This article focuses on principals’ responses related to how ICT has influenced their daily work. During the interviews, we asked principals: “How have advances in ICT influenced your work?” The narrower topic of e-mail emerged from this broader line of inquiry—principals used this question as an opportunity to discuss the impact e-mail has on their work. We recorded interviews using an iPad application and/or digital voice recorders, and interviews lasted between one and two hours. We have used a password-protected electronic database to store all transcriptions and recordings.

Data analysis

We analyzed the interview data in three stages. Stage 1 involved analyzing the interviews using the constant comparative method (Savin-Baden & Major, Citation2012). As part of this process, we read transcripts with the aim of recognizing recurrent themes connected to e-mail use. These themes became distinct codes (e.g., convenient or makes work easier), and each code was assigned a name, such as accountability trail. Stage 2 consisted of reanalyzing each transcript to identify data that fit the codes we had developed prior to analysis, based on a literature review (Merriam, Citation2009)—for example, a learning curve for experienced principals using e-mail.

In Stage 3, we broke up the codes and grouped them together to form categories and subcategories based on participant responses (Gall et al., Citation2005; Merriam, Citation2009; Savin-Baden & Major, Citation2012). For example, codes titled too available and more work were grouped together to form a category titled, increased workload and longer hours. Final analysis resulted in two main categories (or parent codes), titled benefits and challenges. During analysis, we identified four subcategories (or child codes) under the benefits parent code, including convenient and efficient communication, manage workload, and create an accountability trail. Five subcategories emerged from analysis of the challenges parent code, including increased workload and longer hours, high volume of e-mails, and blurring the boundaries between work and home. The findings of the study are discussed in the next section.

Findings

Our findings provide insight into how e-mail influences the work of contemporary school principals. The interviewed principals expressed conflicting views about the ways e-mail has influenced their work. Principals described both perceived benefits of e-mail—such as convenient and efficient communication, ability to better manage their workload, and the ability to document daily communications—and challenges associated with the use of e-mail, including high volume of e-mail messages, extended workdays, increased workload, increased expectations of shorter response times, and blurred boundaries between work and home.

Benefits

Just over half of the sample (54.3%) described e-mail as a welcome addition to their work, as it decreased workload and effectively made their work easier to do on a daily basis. The principals who expressed this sentiment discussed three ways e-mail has been beneficial to their work. The first benefit was allowing principals to easily, quickly, and efficiently communicate with teachers, parents/guardians, and other stakeholders. The second benefit was helping principals manage their workload by allowing them to extend the workday and to complete tasks quickly and efficiently. The third benefit was creating an accountability trail by maintaining an accurate record of tasks, activities, and communications. Each benefit is discussed in detail below.

Convenient and efficient communication

The convenience of being able to remotely communicate with teachers, parents, and other stakeholders using e-mail was the first benefit participating principals mentioned. For example, one principal mentioned that e-mail allows her to “get a lot more done than [she] would be able to otherwise just because [she] can communicate with people whenever [she] get[s] a free minute.” E-mail can be a convenient and efficient communication tool for principals because they can contact parents, teachers, their superintendent, and other stakeholders regardless of the time of day or either party’s location. As one interviewee stated:

I feel as though I’m better prepared for what’s coming at me because of how readily available the communication is. I like it; it’s been a big help for me. Teachers are now using our electronic communications a lot better than they were five years ago…e-mail is a lot easier to get your point across than finding the right time to sit with the person you talk to. I don’t like it to replace face-to-face time, but sometimes it’s more efficient.

According to this principal, it was easier and, at times more effective, to communicate with teaching staff via e-mail. Principals considered this communicative efficiency as one of the key ways e-mail has helped them better manage their workload.

Manage workload

The second benefit of e-mail, according to some of the principals, is that it allows them to manage their workload more efficiently and effectively, because they can complete individual tasks and communicate faster than in the past. For example, one principal mentioned: “I find it simpler. That’s where technology does make things simpler. You don’t have to initial all these things and send them back.” Another principal expressed that the flexible nature of e-mail allows her to manage her workload by working anytime, anywhere:

There is so much good about technology, there are so many fantastic things about technology…I can take my laptop anywhere, including all summer long. I can pull it anywhere; I could be on a trip. All of that stuff was great for the convenience of it. To check my e-mail anywhere, I could be at a meeting and I am accessible. So, all of those great things.

Whether principals are at the school site, at home, or even on vacation, e-mail ensures they are always accessible. Additionally, because e-mail is text-based and each message creates a permanent record, some principals consider e-mail to be an accountability tool.

Accountability trail

Some of the principals also described a third benefit of e-mail: It provides them with an opportunity to document the communication they have with others. E-mail creates an accountability trail and maintains an accurate record of principals’ communications with staff and other stakeholders, cutting down on time spent using traditional documentation methods, such as note taking. Approximately 10% of the sample mentioned accountability as a benefit of using e-mail. For example, one principal stated: “I like it to document. There’s a level of accountability on everyone’s part. If you send an e-mail, there’s a record of it.” Principals spent less time documenting conversations they have with various parties throughout the school day because, increasingly, communication consists of electronic text as opposed to face-to-face conversation. The principals valued e-mail because it allows them to create an accountability trail by documenting their daily communication in an efficient and user-friendly way.

Challenges

For principals, e-mail also has its drawbacks. Study participants described many of these challenges, including: the high volume of e-mail, the extension of the workday, increased workload, increased expectation of shorter response time, and the blurring of boundaries between work and home. Each of these challenges is described in detail below.

High volume of e-mail

At the time of this study, the interviewed principals reported receiving between 30 and 100 e-mail messages daily. More than half of the participants (58.6%) mentioned that the volume of e-mail they received on a daily basis had extended their workday and intensified their workload. As one principal expressed: “E-mail…takes up all the time, and now that we have smartphones you’re always connected…I check every hour, and that’s even at home too.” As a way to reduce the number of e-mail messages they receive on a daily basis, some principals in the study asked staff to refrain from sending them e-mail unless absolutely necessary. For example, one principal stated:

I encourage the staff to cut down the amount of e-mail they send me, as I get a lot from the board. I get it from other organizations. I said “I’d rather you talk to me, face-to-face.” If I go in there, they can ask me a quick question, so they don’t have to e-mail me. And I am not a fast typist so it is really painful for me to respond to an e-mail.

Dealing with a high volume of digital communication proved challenging for many principals, especially given the broad scope of their daily tasks, duties, and activities. Even when teaching staff limited their e-mail correspondence, all principals indicated that answering e-mail increased the amount of time they put into their workday.

Extension of the workday

The high volume of e-mail principals send and receive requires them to extend their already busy workday. On average, principals in Ontario spend 11 hours reading and writing e-mail messages every week (Pollock et al., Citation2015). One of the principals in the sample stated that e-mail, as a form of communication within schools and school boards, leads to “longer hours because you’re sending e-mails all the time.” The principals indicated that they needed to work longer hours to keep up with the volume of e-mail. As one principal explained:

The instant access that thousands of people have to me every day, really lengthens out the job. So, it’s not uncommon for me to do e-mail at night and to do it quite late at night because you can’t get it done in the day. Your workday is extended late into the night, early in the morning before you get to work, and certainly over weekends.

According to our participants, longer work hours is the consequence of being easily accessible to various parties including teachers, parents, and other stakeholders. Responding to e-mail necessitates working outside of regular school hours, including evenings, early mornings, and weekends.

Increased workload

Spending additional workday hours responding to e-mail has increased principals’ workloads. Principals must perform not only the general tasks required in their role, but additional tasks as well. As one principal put it: “It has increased my work considerably and I don’t know how we ever communicated before…I think the use of our communication and where we are now with communication has only, not complicated, but increased the expectation and the workload.” A high volume of e-mail translates into a high volume of tasks: Each e-mail message a principal receives can represent a multitude of tasks for which they are subsequently responsible. Principals must consider whether an e-mail message requires an immediate response, whether it can be set aside before responding, or whether it can be deleted or otherwise categorized into another folder without responding. If a response is necessary, principals need to reflect on what their reply will look like, and whether it would be prudent to respond using face-to-face communication. Additional tasks may be necessary before drafting a response, such as gathering data or other information from reports, the school’s administrative staff, or individual teachers.

Increased expectation of shorter response time

Principals in this study indicated that, in addition to increasing the volume of their work, e-mail has increased the pace of their work. For example, one principal stated: “If you don’t keep up with [e-mail messages] on a daily basis they can quickly inundate you.” E-mail has increased the rate at which others expect principals to do their work. For example, another principal stated:

I think the instant availability of me to you has brought, to all of us, but [especially] school administrators, a sense of urgency that shouldn’t exist. So, when you or anyone else in the educational organization sends me an e-mail, and it arrives, they know it arrives. They can see it on my desktop and check if I read it, deleted it. They know. So, there’s this need to respond and in general, there is a general need to respond within the same business day, or close to, to e-mail queries that come, and sometimes more rapidly than that.

Principals not only receive a high volume of e-mail, but because e-mail systems can now share information with senders about when a message arrives and whether or not it has been read, the senders expect rapid responses. The increased expectation of shortened response time has blurred the boundaries between work and home for many principals.

Blurring the boundaries between work and home

The majority of principals in the study suggested that the boundaries between their workplace and home have blurred. They described feeling pressured to be constantly available to staff, students, parents, and other stakeholders, including in the evening and on weekends. The following principal, who immediately reached for their phone and started responding to e-mail at the hospital shortly after undergoing surgery, best expressed this sentiment:

I am addicted to my iPhone. I constantly check my e-mail. And last week I was out for surgery, the full week, and literally as I came out of anesthesia, I was asking for my iPhone. So as much as I have my autoreply set on, you know, “I’m gone this week and don’t expect to hear from me within a certain span of time until next Monday,” it was literally, my procedure was 10:00 a.m. on Monday morning and by 2:00 p.m. I was starting to respond to people who had sent me e-mail.

Although this principal was dedicated to the job, easy and constant access to e-mail allowed the job to take over their life.

Discussion

For principals, e-mail appears to be both a curse and a boon. On one hand, the principals in this study believed that e-mail helped them “get the job done”; they demonstrated how technological “desk chains” have been broken (Towers et al., Citation2006), which provides them with the ability to work almost anywhere—even the hospital. Principals also argued that e-mail improved stakeholder accessibility, which is consistent with Fullan (Citation2014) and Sheninger’s (Citation2014) research. On the other hand, these same principals felt that e-mail made their job more difficult. Specifically, participants’ comments about increased volume of e-mail and expectations for them to complete tasks in a shorter period of time reflect Galton and MacBeath’s (Citation2002) definition of work intensification, and parallel the findings in the 2012 Alberta Teachers’ Association report. For most of the principals in the study, e-mail was a double-edged sword, simultaneously allowing them to get work done faster while also intensifying their workload. (Hines et al., Citation2008; Pollock et al., Citation2015).

Our findings also suggest that e-mail significantly impacts how principals perform tasks, actions, and activities, as well as when and where they occur. Over 10 years ago, Haughey (Citation2006) predicted that, as a result of e-mail, administrator or principal talk would slowly be replaced by text. At first glance, our findings may appear to simply confirm Haughey’s prediction. However, when we compared our results to other research, such as time-use studies, a different interpretation emerged. Before the Internet, principals’ talk often occurred during informal gatherings and encounters, formal meetings, and phone conversations (Kmetz & Willower, Citation1982; Martin & Willower, Citation1981; Martinko & Gardner, Citation1990); current principals’ communication media are now both traditional (e.g., formal and informal meetings, phone calls) and contemporary (e.g., e-mail). An Ontario time-use study conducted in 2013 (see Pollock, Citation2014; Pollock et al., Citation2015) indicated that in a principal’s average 59-hour work week, they engaged in a number of different kinds of communication (talk-as-text) media.

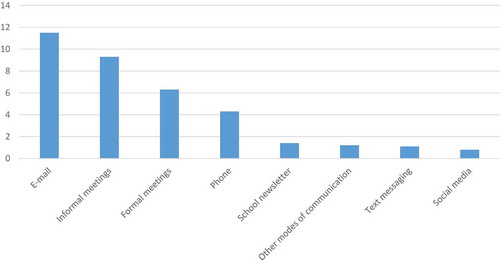

demonstrates that principals in Ontario still spend, on average, 15.6 hours per week on traditional communication media such as meetings (formal, 6.3 hours per week [10%], and informal, 9.3 hours per week [16%]), which translates into approximately 26% of the 59-hour work week. This means that Haughey’s Citation2006 prediction—administrators’ talk being replaced by text—did not happen. In most structured observation studies over the past 40 years, the percentage of principals’ time spent on traditional communication such as meetings (formal/informal, external/internal) has ranged from 4.1% (Bezzina, Citation1998) to 42.57% (Martinko & Gardner, Citation1990). Given that our study participants spend approximately 26% of their time in meetings, contemporary Ontario principals fall into the middle of the historical range: It has not decreased. Although there is no concise way to accurately compare these studies as each has specific methodological nuances, the information presented here does allow readers to determine that principals in Ontario are generally still engaged in various traditional forms of interaction and communication.

Contemporary principals seem to be spending similar amounts of time on “talking media” as their predecessors. What is different, however, is that in addition to formal and informal meetings and phone conversations, contemporary principals now also communicate using some form of electronic text. On top of the 26% of the workday that principals spend in formal and informal meetings, they also engage in approximately another 11.5 hours per week communicating using e-mail. demonstrates some of the other ICT formats principals use. Although traditional communicative methods are still prevalent in principals’ work, they also have an additional layer of “text talk.” The overall outcome is additional work communicating.

Table 1. Principals’ Time Spent on Communication Using Different Forms of ICT.

Gronn (Citation1983) argued that “talk is the work” (p. 2) of school principals and is the key resource principals use to carry out their work. If talk is the medium principals use to “get the job done,” traditionally through phone calls and in formal and informal meetings, then e-mail can be considered an extension of this “talk work”; Haughey’s Citation2006 prediction has not yet materialized. Rather, what appears to be happening is that, in addition to traditional ways of talking and communicating, principals now have an additional layer of electronic text-as-talk, and this appears to bring both benefits and challenges.

Superficially, it may appear that school districts could limit the amount of e-mail, especially forwarded e-mail sent to principals. Further, principals could mitigate some of the challenging aspects of e-mail by prioritizing and responding to only the most important messages, limiting the hours spent responding to e-mail messages, and reducing where and when they check their e-mail after school hours. However, reducing the challenges of e-mail communication is not as simple as setting priorities or boundaries: These challenges are characteristic of a larger phenomenon—work intensification. As mentioned earlier, work intensification is generally defined by a combination of two or more of the following: increased volume of the same expected work, additional work tasks added to the increased volume of current work, increased expectations that the work will be completed within a shorter time period, and the notion that work is to be completed with a reduced number of resources (Alberta Teachers’ Association, Citation2012; Allan et al., Citation1999; Green, Citation2004; Pollock et al., Citation2015). The same principals who acknowledge the many positive aspects of using e-mail to communicate at work also indicated that they are experiencing an increased volume of regular work, and are having to do this work within a reduced time period.

Conclusion

E-mail influences where principals conduct their work and how they perform the tasks, activities, and practices that comprise their workday. As a result, e-mail facilitates much of the work intensification contemporary principals are experiencing. Although principals report that e-mail allows for convenient and efficient communication and provides an opportunity to better manage workload and document daily communications, education scholars and stakeholders need to consider whether the benefits outweigh the challenges. The challenges principals outlined in this study included increased volume of e-mail, extended workdays, increased expectations of shorter response time, and a blurring of the boundaries between work and home. All of these challenges combine to intensify principals’ work, making them feel as if they are constantly on call and preventing them from achieving work–life balance. For principals, e-mail is a double-edged sword: It is a tool that simultaneously manages and intensifies their workload, and has transformed the principalship into a position without defined work hours and a set workplace.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Education's Leadership Development and School Board Governance Branch and The Western Academic Development Fund.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alberta Teachers’ Association. (2012). The new work of teaching: A case study of the worklife of Calgary public teachers. Retrieved from http://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/Publications/Research/

- Allan, C., O’Donnell, M., & Peetz, D. (1999). More tasks, less secure, working harder: Three dimensions of labour utilisation. Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(4), 519–535.

- Anderson, R. E., & Dexter, S. (2005). School technology leadership: An empirical investigation of prevalence and effect. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41(1), 49–82.

- Anderson, R. E., & Dexter, S. L. (2000). School technology leadership: Incidence and impact (1998 National Survey Research Report No. 6). The University of California eScholarship. Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/76s142fc

- Applebaum, H. A. (1992). The concept of work: Ancient, medieval and modern. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

- Ballet, K., & Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Struggling with workload: Primary teachers’ experience of intensification. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(8), 1150–1157.

- Bezzina, C. (1998). The Maltese primary school principal: An observational study. Educational Management and Administration, 26(3), 243–256.

- Bottery, M. (2016). Not so simple: The threats to leadership sustainability. Management in Education, 30(3), 97–101.

- Brockmeier, L. T., Sermon, J. M., & Hope, W. C. (2005). Principals’ relationship with computer technology. NAASP Bulletin, 89(643), 45–57.

- Cho, V., & Jimerson, J. B. (2017). Managing digital identity on twitter. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45(5), 884–900.

- Cho, V. (2016). Administrators’ professional learning via twitter. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(3), 340–356.

- Davies, P. M. (2010). On school educational technology leadership. Management in Education, 24(2), 55–61.

- DiPaola, M., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2003). The principalship at a crossroads: A study of the conditions and concerns of principals. NASSP Bulletin, 87(634), 43–65.

- Duxbury, L., Higgins, C., Smart, R., & Stevenson, M. (2014). Mobile technology and boundary permeability. British Journal of Management, 25(3), 570–588.

- Fineman, S. (2003). Understanding emotion at work. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Fineman, S. (2012). Work: A short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Flanagan, L., & Jacobsen, M. (2003). Technology leadership for the twenty-first century principal. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(2), 124–142.

- Fournier, P.-S., Montreuil, S., Brun, J.-P., Bilodeau, C., & Villa, J. (2011). Exploratory study to identify workload factors that have an impact on health and safety: A case study in the service sector (Research Report No. R-701). Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail (IRSST). Retrieved from https://www.irsst.qc.ca/media/documents/PubIRSST/R-701.pdf

- Franke, F. (2015). Is work intensification extra stress? Journal of Personnel Psychology, 14(1), 17–27.

- Fullan, M. (2014). The principal: Three keys to maximizing impact. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Gall, J. P., Gall, M. D., & Borg, W. R. (2005). Applying educational research: A practical guide (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education Inc.

- Galton, M., & MacBeath, J. (2002). A life in teaching? The impact of change on primary teachers’ working lives (National Union of Teachers Research Report). The University of Cambridge Faculty of Education. Retrieved from https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/people/staff/galton/NUTreport.pdf

- Green, F. (2004). Work intensification, discretion, and the decline in well-being at work. Eastern Economic Journal, 30(4), 615–625.

- Gronn, P. (1983). Talk as the work: The accomplishment of school administration. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(1), 1–21.

- Gurr, D. (2000). The impact of information and communication technology on the work of school principals. Leading & Managing, 6(1), 60–73.

- Gurr, D. (2004). ICT, leadership in education and e-leadership. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 25(1), 113–124.

- Haughey, M. (2006). The impact of computers on the work of the principal: Changing discourses on talk, leadership and professionalism. School Leadership & Management, 26(1), 23–36.

- Hines, C., Edmonson, S., & Moore, G. W. (2008). The impact of computer technology on high school principals. NASSP Bulletin, 92(4), 276–291.

- Hvidston, D. J., Hvidston, B. A., Range, B. G., & Harbour, C. P. (2013). Cyberbullying: Implications for principal leadership. NASSP Bulletin, 97(4), 297–313.

- Kmetz, J. T., & Willower, D. J. (1982). Elementary school principals’ work behavior. Educational Administration Quarterly, 18(4), 62–78.

- Leithwood, K. (2001). School leadership in the context of accountability policies. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 4(3), 217–235.

- Leithwood, K., & Azah, V. N. (2014). Elementary principals’ and vice-principals’ workload studies: Final report. The Ontario Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/memos/nov2014/FullElementaryReportOctober7_EN.pdf

- Leithwood, K., Steinbach, R., & Jantzi, D. (2002). School leadership and teachers’ motivation to implement accountability policies. Educational Administration Quarterly, 38(1), 78–94.

- Martin, W. J., & Willower, D. J. (1981). The managerial behavior of high school principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 17(1), 69–90.

- Martinko, M. J., & Gardner, W. L. (1990). Structured observation of managerial work: A replication and synthesis. Journal of Management Studies, 27(3), 329–357.

- Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miller, P. (2016). Exploring school leadership in England and the Caribbean: New insights from a comparative approach. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Niesche, R. (2011). Foucault and educational leadership: Disciplining the principal. London, UK: Routledge.

- Pollock, K. (2014). Principals’ work in contemporary times: Final report. The University of Western Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.edu.uwo.ca/faculty-profiles/docs/other/pollock/OME-Report-Principals-Work-Contemporary-Times.pdf

- Pollock, K., & Hauseman, D. C. (2015). Principal leadership in Canada. In H. Arlestig, C. Day, & O. Johansson (Eds.), A decade of research on school principals: Cases from 24 countries (pp. 202–232). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Pollock, K., Wang, F., & Hauseman, D. C. (2015). Complexity and volume: An inquiry into factors that drive principals’ work. Societies, 5(2), 537–565.

- Robson, C., & McCartan, K. (2016). Real world research (4th ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Ryan, J. (2006). Inclusive leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Sauers, N., & Richardson, J. (2015). Leading by following: An analysis of how K–12 school leaders use twitter. NASSP Bulletin, 99(2), 127–146.

- Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2012). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. London, UK: Routledge.

- Schiller, J. (2003). Working with ICT: Perceptions of Australian principals. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(2), 171–185.

- Sheninger, E. (2014). Digital leadership: Changing paradigms for changing times. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Shields, C. M. (2010). Transformative leadership: Working for equity in diverse contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(4), 558–589.

- Spillane, J. (2015). Leadership and learning: Conceptualizing relations between school administrative practice and instructional practice. Societies, 5(2), 277–294.

- Starr, K. (2012). Problematizing “risk” and the principalship: The risky business of managing risk in schools. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 40(4), 464–479.

- Starr, K., & White, S. (2008). The small rural school principalship: Key challenges and cross-school responses. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 23(5), 1–12.

- Towers, I., Duxbury, L., & Thomas, J. (2006). Time thieves and space invaders: Technology, work and the organization. Management, 19(5), 593–618.

- Volante, L., Cherubini, L., & Drake, S. (2008). Examining factors that influence school administrators’ responses to large-scale assessment. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 84, 1–30.

- Williamson, J., & Myhill, M. (2008). Under “constant bombardment”: Work intensification and the teachers’ role. In D. Johnson & R. Maclean (Eds.), Teaching: Professionalisation, development and leadership (pp. 25–44). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Yee, D. L. (2000). Images of school principals’ information and communications technology leadership. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, 9(3), 287–302.

- Yu, S. (2014). Work–life balance: Work intensification and job insecurity as job stressors. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 24(3), 203–216.