ABSTRACT

This research investigated how a leadership team enacted wellbeing promotion in a Catholic Preparatory to Year 12 all-girls school using the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing 12 Pathways Model (GIW-12P). This qualitative case study purposively selected participants (n = 25) and collected data over an eight-week period using surveys and semi-structured focus group discussions. Thematic analysis was conducted in four phases with three key findings. Firstly, the GIW-12P as a tool proved highly effectual as a model. Secondly, applying the model surfaced areas of effectual wellbeing promotion while also illuminating gaps in practices and drawing attention to areas for further action. Thirdly, the “how” of the application surfaced as an opportunity for school-wide collaboration linked to core beliefs and quality outcomes for students, teachers, and all participants. Using the GIW-12P model provides new knowledge to policymakers and researchers in the field of practice. When collaboratively used as an analysis tool, the GIW-12P created an intersectionality with the concept of wellbeing within this community. When applied by a team to investigate wellbeing promotion, the GIW-12P surfaces information key to effective decision-making for leaders regarding the utilisation (i.e., allocation and deployment) of human and financial resources and educational policy to drive school-wide wellbeing promotion.

Introduction

Research continues to surface concerns regarding the significant problem that schools face regarding how to promote wellbeing. A study by Thomas et al. (Citation2022) of 19,240 young people found that 39% of students reported at least moderate to high levels of emotional distress. Similarly, a Mission Australia study (Citation2022) of 18,000 Australian young people identified that four in ten (41.5%) described that the most significant challenges to their wellbeing were directly linked to challenges experienced in school (Mission Australia, Citation2022). These challenges included academic pressure, high workload, challenges with teachers, and learning difficulties (Mission Australia, Citation2022). Likewise, in Australia, Brennan et al. (Citation2021) also noted a significant increase in the proportion of young people with wellbeing concerns, rising from 18.6% in 2012 to 26.6% in 2020, with girls far more likely to experience wellbeing issues than boys.

Literature indicates that teachers have expressed concerns about their wellbeing and fostering their students’ wellbeing. Globally, teachers report issues with maintaining their wellbeing (Billett et al., Citation2023; Education & Solidarity Network, Citation2021), suggesting this is due to role complexity and stress (Buric et al., Citation2019). A study of 3000 Australian school teachers (McCallum, Citation2021) outlined significant impacts on teacher wellbeing, including balancing work and family demands, dissatisfaction with work roles, workload issues, and ever-increasing workload demands. Furthermore, teachers have reported difficulties in supporting student wellbeing and have expressed the need to learn how to design interventions that support and enhance student wellbeing (McCallum, Citation2021). Given that teacher wellbeing and teacher concerns about promoting student wellbeing are critical issues, employing approaches to wellbeing promotion becomes a necessary activity for school communities.

While it is acknowledged that promoting wellbeing in schools is important, a lack of clarity exists on “how this is done.” McCallum and Price (Citation2016) highlight a causal relationship between teachers and students: teachers need to be well for students to be well. Timperley (Citation2015) offers insight describing the bidirectional impact of student-focused interventions on teachers’ wellbeing and teacher-focused interventions on student wellbeing. Further literature describes the relationship between teachers and student wellbeing as complex (Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, Citation2016), with teacher wellbeing impacting student wellbeing (Harding et al., Citation2019) and reciprocally student wellbeing impacting teacher wellbeing. As a result of this complex and bidirectional relationship, educators appear to grapple with understanding and supporting wellbeing promotion in school communities.

Furthermore, complexities also exist regarding how wellbeing is promoted in relation to decision-making, planning, and implementation of effectual wellbeing programs and activities. For example, a general review of the efficacy and effectiveness of Australian school wellbeing programs by Carslake and Dix (Citation2020) identified that only 23% of programs provided concrete evidence of some impact on student wellbeing. Thus, wellbeing promotion is a much-needed priority within schools, and more precise knowledge of effectual practices is required to maximize student and teacher wellbeing outcomes.

For wellbeing to be effectively embedded as a school-wide approach, wellbeing promotion must be a shared responsibility of all stakeholders and demonstrated in policies, curriculum, structures, and practices (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023; McCallum & Price, Citation2016). Evidence about how wellbeing is promoted (talked about) and evidenced (actions) within educational contexts is demonstrated in the leadership behaviors and school-based artifacts, discourses, and processes within an educational context (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023). However, while school communities endeavor to implement best practices for wellbeing promotion (Govorova et al., Citation2020), there is an absence of a consensus about specific frameworks or guidelines on how to shape implementation and evidence of wellbeing promotion within schools. There is also a lack of evidence about how student and teacher wellbeing can be promoted without an explicit framework to guide decision-making (Powell & Graham, Citation2017b), contributing to a fragmented and ad approach to promoting wellbeing (Powell & Graham, Citation2017b).

To meet the research-to-practice gap and reduce ambiguity around wellbeing promotion within schools, Carter and Andersen (Citation2019, Citation2023) suggest using the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing using 12 Pathways (GIW-12P) as an evidence-based research-driven tool to investigate wellbeing promotion pathways. Growing Inclusive Wellbeing using 12 Pathways (GIW-12P) does not specify a particular definition of wellbeing. However, it outlines the importance of the whole school community having a shared understanding of wellbeing within their context and that this understanding aligns with systemic definitions of wellbeing. This suggestion in the literature leads to the development of the key research question informing this study: How can the use of Growing Inclusive Wellbeing through 12 Pathways (GIW-12P) inform the leadership of effectual wellbeing promotion within an educational context?

Literature Review

This literature review examines the concept of wellbeing and the leadership of effectual wellbeing promotion within an educational context and is structured into four sections. Firstly, conceptualizing wellbeing a basis for exploring wellbeing in educational contexts. Secondly, exploration of the wellbeing needs of both students and teachers followed by an outline of complexities associated with implementing wellbeing promotion programs. Lastly, consideration of how the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing 12 Pathways Model (GIW-12P) provides new knowledge that can support and inform leaders’ decision-making regarding school-wide wellbeing promotion.

Conceptualising Wellbeing

Much ambiguity exists in how wellbeing is conceptualized, defined, understood, and promoted in school contexts (Powell & Graham, Citation2017a). Furthermore, significant contradiction is also evident in how wellbeing is defined and promoted globally, with several different labels to describe the concept (e.g., mental health, subjective wellbeing, psychological wellbeing) (Crenguța et al., Citation2023; Huang et al., Citation2022). Moreover, while wellbeing definitions in the literature have continued to evolve, there also continues to be a lack of sector-wide agreement regarding what wellbeing is or whether the language utilized should be “wellbeing” or “wellbeing” (Kern et al., Citation2020).

Carter and Andersen (Citation2023) identified that wellbeing is complex, dynamic, and changeable, consequently inhibiting a universal definition (Maggino & Alaimo, Citation2021), resulting in various approaches to conceptualizing wellbeing within school systems. Likewise, McCallum and Price (Citation2016) stated that wellbeing, while universally sought after and underpinned by positive notions, is inherently personal and integral to our identity. Similarly, Fraillon (Citation2004) views wellbeing as a sustainable state characterized by positive mood, resilience, and satisfaction with oneself, relationships, and school experiences Ultimately, the conceptualization of wellbeing is then influenced by what presents as a dynamic interplay of individual, family, and community beliefs, values, culture, and opportunities, which evolve over time. Additionally, R. White and Wyn (Citation2013) further connect such conceptualization of wellbeing to the social and relational dimensions of wellbeing, thereby emphasizing that “identities are experienced and actively produced by young people, but these productions and experiences are contingent on social and institutional relationships” (p. 12).

The approach to wellbeing in educational settings has evolved significantly, with the concept of wellbeing often being broadly applied (McCallum & Price, Citation2016). Furthermore, it is rarely explicitly defined often due to competing priorities within schools and ambiguity in conceptualizations of wellbeing (Soutter, Citation2011). However, in recent times, the conceptualization of wellbeing within many school contexts has broadened to include universal interventions and programs designed to enhance social and emotional skills and psychological health more broadly across the entire youth population (Mahoney et al., Citation2021).

Thus, wellbeing is a multifaceted concept that has been conceptualized in this study through the lens of Diener’s notion of subjective wellbeing, which includes two primary components: affect, (i.e., comprising feelings, emotions, and moods), and secondly, life satisfaction, which is related to all life domains such as school, family, and work (Diener, Citation2009; Eid & Larsen, Citation2008). This definition has been applied here as there is broad consensus that these components are part of an individual’s wellbeing (Das et al., Citation2020). Diener’s (Citation1984) notion of subjective wellbeing suggests that individual’s make a cognitive appraisal of three critical components: (1) overall life satisfaction, (2) levels of positive affect, and (3) low-level unpleasant affect (Diener, Citation2009). According to the authors, this definition offers a more nuanced understanding of the multiple facets of subjective wellbeing (Carter et al., Citation2023). As such, this stance considers an individual’s cognition and feelings to inform the evaluation of life satisfaction and are subjective and unique to each person’s wellbeing. Thus, Diener’s definition matters within this study as the authors view wellbeing as a “balanced life experience where an individual’s wellbeing needs to be considered about how an individual feels and functions across a range of areas, including cognitive, emotional, social, and physical elements” (Carter & Andersen, Citation2019, p. 23).

Wellbeing Needs of Students and Teachers

Wellbeing needs of students and teachers continue to surface in the literature both within Australia and internationally. Extensive research has been conducted on wellbeing and its close links with learning, demonstrating an increasing understanding of how wellbeing and effective learning are integrally and dynamically connected in the development of students’ wellbeing (Carter & Andersen, Citation2019; Clarke et al., Citation2015; McCallum & Price, Citation2016). This means schools have an unprecedented opportunity to support student wellbeing and academic development (McCallum & Price, Citation2016; Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs [MCEETYA], Citation2008).

Furthermore, there is consensus that post COVID-19 student and teacher wellbeing levels have remained concerningly low (Billett et al., Citation2023; Fray et al., Citation2023), with schools called upon to promote wellbeing (Norwich et al., Citation2022). Teacher wellbeing and workforce concerns impacting schools across Australia are well documented in the literature (McCallum & Price, Citation2016; M. A. White & McCallum, Citation2020). McCallum and Price (Citation2016) emphasize that teachers’ wellbeing is essential for students’ wellbeing. While promoting the wellbeing of both teachers and students is essential for educational communities, several challenges exist in the intricate and bidirectional relationship between teacher and student wellbeing, where teacher wellbeing influences student wellbeing and vice versa (Harding et al., Citation2019; Oberle & Schonert-Reichl, Citation2016; Timperley, Citation2015). Consequently, addressing the multifaceted dimensions of wellbeing (physical, social, cognitive, spiritual, and emotional) is imperative to promote the wellbeing of both teachers and students (M. A. White & McCallum, Citation2020). Given that wellbeing concerns are being identified as a critical issue for students and teachers across the globe, school leaders then play an important role in employing a precise school-based approach to enabling wellbeing promotion within their communities to meet the wellbeing needs of all the community.

Challenges in Implementing Wellbeing Promotion Programs

Despite the acknowledged importance of promoting teacher and student wellbeing in educational settings, implementing wellbeing promotion programs is fraught with challenges, particularly regarding the conceptualization and language surrounding wellbeing. A literature search on wellbeing programs reveals several challenges in implementing wellbeing promotion. Evidence about how wellbeing is promoted (talked about) and evidenced (actions) within educational contexts is demonstrated in the leadership behaviors and school-based artifacts, discourses, and processes within an educational context (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023). Firstly, programs exhibit differing or conflicting language about wellbeing, either focusing on mental health rather than wellbeing, switching between wellbeing and mental health as interchangeable concepts or using “mental health” and “wellbeing” together without explaining their relationship between both (Norwich et al., Citation2022). Thus, further adding to ambiguity about wellbeing.

Secondly, evidence indicates a lack of consensus about the components of effective wellbeing promotion. For example, The Australian Student Wellbeing Framework (Australian Government, Citation2020) outlines five key elements of wellbeing promotion: leadership, inclusion, student voice, partnerships, and support for the whole school community to promote student wellbeing, safety, and learning outcomes. Seligman’s Model (Seligman, Citation2011) identifies five key factors essential for contributing to wellbeing: positive emotion (P), engagement (E), positive relationships (R), meaning (M), and accomplishments and achievements (A). McCallum and Price’s Model of Holistic Wellbeing (Citation2016) highlights indicators of wellbeing that include contextual factors such as life events and socio-demographic factors, along with cognitive factors, affective factors such as positive and negative states as contributing to subjective wellbeing where there is a global satisfaction also seen as happiness or positive state affect or satisfaction with life. Likewise, Noble et al. (Citation2008) advocate for seven enablers of wellbeing in educational contexts: physical and emotional safety, pro-social values; supportive, inclusive, and caring school community; social and emotional learning; a strengths-based approach; a sense of meaning and purpose; a healthy lifestyle with connection to the constructs of mental health; academic achievement; and a prosocial and responsible lifestyle (Noble et al., Citation2008). Thus, ambiguity is understandable when there is little precise alignment of the concept of wellbeing and is further complicated when frameworks and programs present theoretically different understandings of wellbeing.

School leaders and their communities are thus confronted with ambiguity and likely overwhelmed by the plethora of wellbeing promotion support programs. For example, every Australian state or territory has hundreds of programs to choose from to support wellbeing promotion within their communities. For a school leader, the challenge becomes evident when considering the ambiguous connections between wellbeing and existing legislation and policy. These ambiguous connections must inform frameworks and determine which programs can be implemented to complement them. Complicating this is the need for more clear evidence regarding which programs best support wellbeing promotion. Complexities also exist within the wellbeing space when teachers select wellbeing programs and activities to utilize within their school communities. For example, a general review of the efficacy and effectiveness of Australian school wellbeing programs by Carslake and Dix (Citation2020) identified that only 23% of programs provided concrete evidence of a significant impact on student wellbeing. Wellbeing promotion is needed within schools, and more precise knowledge of effectual practices is required to maximize student and teacher wellbeing outcomes.

This implementation challenge must be undertaken while struggling with workload (McCallum, Citation2021) and struggling to differentiate curriculum for diverse learners (Mission Australia, Citation2022). Therefore, the literature reports that schools are laboring to promote wellbeing. Carter and Andersen’s (Citation2019) research explores the pragmatic applications of embedding an education-wide focus on wellbeing. In 2019, GIW-12P was developed after Carter and Andersen reviewed existing literature on wellbeing in education and positive psychology and synthesized this information into pathways for wellbeing promotion. In addressing wellbeing promotion within an educational context, the GIW-12P uses an evidence-based research-driven pathway to investigate evidence of wellbeing promotion in a school community with a view of surfacing wellbeing practices, discourse, and processes.

Use of the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing within Educational Contexts

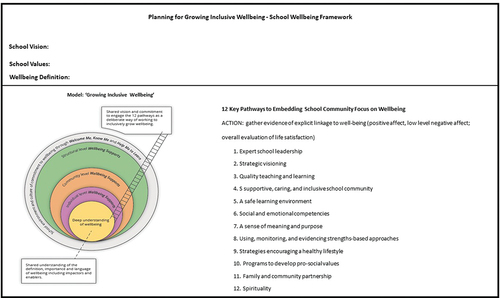

Carter and Andersen’s (Citation2019) research synthesizes current research within educational contexts. It contributes to the education field by developing a model aligning with the breadth of frameworks and developing the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing Model (GIW-12P). Research suggests that aligning a school vision with school values and ways of working unpins a culture of inclusion (Carter & Abawi, Citation2018). Furthermore, research suggests that a feeling of inclusion where a person experiences a sense of belonging can contribute to wellbeing promotion (McCallum & Price, Citation2016) as the feeling of being included promotes positive affect, a component of the construct of wellbeing (Diener, Citation2009). This connection and alignment are evidenced in GIW-12P, where wellbeing promotion is inclusive within the philosophy of the educators and their chosen pedagogical approaches, and this was why the model was selected for this study, as depicted in the GIW-12P (see ).

Figure 1. Growing inclusive wellbeing (GIW-12P).

Furthermore, the model links to an ecological system theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005), which posits that a sequence of interconnected environmental factors influences a person’s development. The model depicts this interrelationship, showing the individual within their family as part of the school community, the general community, and an international community while acknowledging the nuanced elements that influence individuals and their wellbeing. GIW-12P (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023) model includes five components, represented visually in concentric circles like Bronfenbrenner’s ecology theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). Each process explores various levels, including an inner circle, and presents a deep understanding of wellbeing. An individual level of wellbeing support, a community level of wellbeing support, a structural level of wellbeing support, and the educational context and environmental culture provide an ecological and contextual commitment to wellbeing. These layers are interconnected and equally important to supporting individual and community wellbeing. Promoting wellbeing using the GWI-12P model identifies 12 pathways that school communities can use to identify the practices, behaviors, artifacts, discourses, and processes for leadership of effectual wellbeing promotion within an educational context.

Materials and Methods

This study used a qualitative case study methodology to effectually investigate the research question: How can the use of Growing Inclusive Wellbeing through 12 Pathways (GIW-12P) (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023) inform the leadership of effectual wellbeing promotion within an educational context? According to Carter (Citation2020), case study methodology surfaces understandings about “complex contextual conditions and the behaviour of people in these contexts” (p. 304). This study was part of a larger research study into school wellbeing promotion (H19REA269) that investigated the understanding of wellbeing, how educators promoted the wellbeing of children/young people and adults in educational settings, and what informed the judgments around effectual wellbeing promotion and effectual wellbeing practices in educational contexts in nine schools (involving 77 participants), across two Australian states where principals self-identified their school as having effectual wellbeing practices. Only one school site used the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing through 12 Pathways (GIW-12P) (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023), and this is what is reported in this paper.

Throughout the study, the researcher held the Director of Wellbeing and Inclusion role within the case study educational site, which focused on promoting wellbeing. Reflexivity was deliberately used to address the dual role of researcher and Director of Wellbeing in the research site. The researcher worked with two critical friends, which involved collaborative and multifaceted practices (Olmos-Vega et al., Citation2023) of self-critique to evaluate subjective and context influences such as attitude, perspective, and voice, in relation to the participants, the study, and the context (Alexander, Citation2017). The researcher used journal reflections to capture insights and the reflexivity of the self.

Participants

Participants were purposively selected from a single Pre to year 12 Catholic all-girls school site. Purposive sampling enabled the selection of knowledgeable participants (n = 25) with relevant experience to inform the research questions (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2005). Twenty-three were teaching staff (nine were teacher leaders), and two were social workers. Of the nine teacher leaders, seven were female teacher leaders (e.g., leaders of learning, year-level coordinators), and two were male teacher leaders (e.g., Director of Middle School). Nine leaders participated in Phase 1 (survey) and Phase 2 (Focus Group 1). Phase 3 (Focus Group 2) involved eight participants, seven of whom were female, and all had some form of teaching role, with one participant also taking part in the survey and Focus Group 1. Phase 4 (Focus Group 3) involved 11 participants (one participant was an executive leader who also took part in Phase 1 and Phase 2, three were middle-level teacher leaders, and the remaining seven were classroom teachers).

Data Collection and Analysis

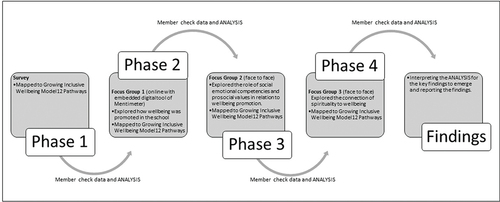

Data was collected from 25 participants in four phases (see ) using a survey and three focus group discussions (see ).

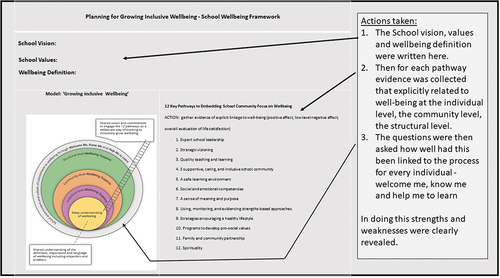

In Phase 1, a paper-based questionnaire was used to survey participants. The survey included quantitative demographic details (see ) and asked participants to describe and share examples of how they were promoting wellbeing (see ). This initial data was then mapped onto the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing using 12 Pathways (GIW-12P). Phase 2 was the first focus group where participants discussed the data from the survey, explored wellbeing promotion in more detail, and shared artifacts to evidence points raised. Phase 3 involved the second focus group, which used the data from the survey and focus group one to drill down into the role of social-emotional competencies and pro-social values about wellbeing promotion, sharing artifacts as examples of how wellbeing was being promoted. Phase 4 involved a third focus group that used the survey’s data and focus groups one and two to understand how spiritual wellbeing was understood and encouraged.

Table 1. Survey participant characteristics.

Table 2. Survey questions.

Focus Group 1 engaged in an online discussion with the embedded digital tool Mentimeter used to capture data regarding multiple-choice, short-answer, and discussion-based questions developed from themes emerging in the phase 1 survey responses. The participants’ anonymous responses were then displayed on computer screens for all participants to view, and participants could then add to their previous responses (as participants could have up to 5 responses). Two face-to-face focus group conversations were conducted (Focus Group 2 and Focus Group 3). Participants were provided with post-it notes to document additional thoughts and evidence about how wellbeing is promoted within the context. In Phase 4, Focus Group 3 explored the data, particularly where there was an evidence gap in wellbeing promotion. In essence, the participants were sharing data and analyzing the shared data to add meaning and insight further during Phases 2, 3 and 4.

The data was thematically categorized in alignment with the GIW-12P (see ). Using Cohen et al. (Citation2017) data analysis process, data was interrogated in four stages: 1) generating units of meaning, 2) ordering units of meaning, 3) structuring narratives, and 4) interpreting the data. Inform the findings. Following the final focus group, all data was organized into a coherent narrative with artifacts used as evidence of points made. All data was then analyzed as a whole data set and cross-checked with Phases 1, 2, 3, and 4 to ensure the emerging narrative aligned with the data. Participants and critical friends (academic mentors) were invited to validate the researcher’s interpretations of the emerging findings to ensure appropriate intent had been captured throughout the process. Journalling throughout the data collection phases allowed the researcher to reflectively interrogate the data, search for meaning about the data revealed, and then check both transcripts and analysis with participants during focus group discussion.

Results and Discussion

Survey and focus group data highlighted the emergence of twelve general themes with data aligning to each pathway in the GIW-12P: expert school leadership, strategic visioning, quality teaching and learning, a supportive caring inclusive community, creation of a safe learning environment, a sense of meaning and purpose, social and emotional competencies, monitoring of evidencing of strengths-based approaches, strategies that encourage a healthy lifestyle, the development of pro-social values, family and community partnerships, and spirituality. A further drill-down revealed three key themes, which will be reported here: 1) the GIW-12P as a tool; 2) the “how” of the use of the GIW-12P; and 3) outcomes for the school community from using the GIW-12P.

The GIW-12P as an Analysis Tool

All study participants were given the GIW-12P model and engaged in an in-depth ongoing discussion regarding wellbeing and what constitutes wellbeing. This led to the development of a shared understanding of wellbeing and ways that it could or should be evidenced to explore the connection between enacted and effectual wellbeing practices. The GIW-12P model was used as an analysis tool to surface these practices. Throughout the survey and focus group conversation, the GIW-12P was identified as a useful tool for building up the “pieces of the puzzle” and identifying “pockets of good practice,” whereby the pathways provided the researcher with a lens for further reflection. Using the pathways surfaced strengths and weaknesses in implementing wellbeing that had not been previously highlighted within the school context. The GIW-12P tool enabled the connections to be made that illuminated what areas could be promoted, activities that might be archived, and how best to align human and financial resources to promote and enhance student and teacher wellbeing.

GIW-12P effectiveness as a tool was evidenced when exploring the findings and insights from the Spirituality pathway. Interestingly, the participants did not explicitly connect spirituality to wellbeing promotion within their context until the researcher made the conceptual connection. All survey and focus group participants indicated that spirituality was essential to their overall wellbeing; however, participants in both survey responses and group discussions identified deepening the understanding of spirituality concerning wellbeing promotion as required further exploration and development within the school. Importantly, the GIW-12P tool enabled the researcher to enquire further into the Spirituality pathway and enacted the fourth focus group that explored spirituality.

The spirituality focus group was informed by contemporary literature, which has surfaced that spirituality and spiritual wellbeing are important in promoting general wellbeing (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023; Eckersley, Citation2007; Grieves, Citation2007). Grieves (Citation2007) suggests that spirituality is a starting point for wellbeing, while Eckersley (Citation2007) defines spirituality as “a deeply intuitive, but not always consciously expressed sense of connectedness to the world in which we live” (p. 54). De Souza (Citation2009) describes spirituality as including all religions and connections to a higher being. This informed the researcher’s questioning in the focus group, whereby participants were asked to describe spiritual wellbeing. Participants highlighted connection, community, faith, and mindfulness as key activities in promoting their spiritual wellbeing. Several participants also stated that they engaged in some form of promotion of their spiritual wellbeing. For example, “engagement with religious education programs aligned with values and traditions,” “connecting with liturgy prayer,” and “participating in moments of stillness.”

Further evidence of the effectiveness of applying the GIW-12P as a tool is evidenced in exploring quality teaching and learning and its nexus with wellbeing. Research has found worldwide that quality teaching and capable teachers are among the most influential factors in student outcomes and achievement (McCallum & Price, Citation2016). Six out of nine participants agreed with the survey statement, “I think that all members of the school community accept responsibility for developing and sustaining quality supportive teaching and learning that supports wellbeing.” Identified in both the survey and focus group conversations, feedback and coaching were strategies identified by the participants as assisting in developing teacher expertise and, in turn, promoting teacher wellbeing. For example, one teacher reported that “the coaching process had been happening for about 18 months, which began with the leaders accessing the necessary training to undertake coaching conversations. This teacher reported that coaching was a change of culture for this school environment, commenting that it was both a challenging and rewarding process that the school could build upon to enhance wellbeing further.”

GIW-12P provided an important lens when exploring quality teaching and learning, which is the core business of educational settings. Using the GIW-12P tool identified further areas for the school context to explore and ways that the community could understand the nexus between quality teaching and learning and wellbeing promotion for teachers and students. For quality teaching and learning to occur, teachers need to have positive wellbeing (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023; Education & Solidarity Network, Citation2021; McCallum & Price, Citation2016; Powell & Graham, Citation2017a). The GIW-12P model surfaced that the participants identified that overall life satisfaction (a component of wellbeing) occurred when collaboration with others (a component of wellbeing). This was further explored by the participants who discussed the feedback and coaching process utilized within the school explicitly helped promote teacher wellbeing. Using the GIW-12P tool surfaced responses that feedback and coaching helped promote teacher wellbeing. It is suggested here that coaching can be used to build a learning culture that further enhances wellbeing promotion.

The “How” of Using the GIW-12P

GIW-12P provided the vehicle to connect people, practices, and shared language within the school community. All participants reported that the collaborative process of applying the GIW-12P as an analysis tool across all areas of the school was highly worthwhile. Using the GIW-12P tool and aligning it within the survey and focus group enabled the participants to provide evidence of wellbeing promotion through the various lenses of the community (school leader, teacher, social worker, student, and family), thereby creating an intersectionality to the concept of wellbeing within this community.

For student wellbeing to effectively be embedded, it needs to be a shared responsibility of all stakeholders and demonstrated in policies, curriculum, structures, and practices (Carter & Andersen, Citation2019; McCallum & Price, Citation2016), evidenced in practice when exploring the GIW-12P, social and emotional competencies. All participants in the survey indicated that students’ social and emotional competencies were well-developed within the school community. Eight focus group participants identified several ways that students learn social and emotional skills that support the student’s social skill development and enhance positive affect and overall wellbeing. These included the Wellbeing, Relationships, Agency, and Personal Responsibility (WRAP) curriculum, circle time, the 5-point scale, and the school’s restorative practices. Participants acknowledged that the WRAP program supported students by providing wrap-around support, with one participant stating, “Students are provided wrap-around support, which is an approach that brings the systems of support together to ensure careful monitoring and review.” One participant also explicitly linked the development of students’ social and emotional competencies to the school’s use of restorative practices, stating that “restorative practices place relationships at the centre of all we do.” Another participant further supported this notion by stating, “By using restorative practices, we support students to develop social and emotional competencies such as empathy, awareness of others, and the necessary skills to resolve conflict competently.” GIW-12P and the associated processes enabled key conversations to occur within the educational context about using social and emotional competencies to promote the wellbeing of students and staff. It helped surface the key components of wellbeing through strengthening positive relationships, enhancing individual positive affect, life satisfaction, and overall wellbeing.

Within the survey and focus group processes aligned with the GIW-12P, participants articulated a crucial element in creating a sense of belonging and promoting a sense of wellbeing. Brunzell et al. (Citation2015) posited that a safe learning environment is established when students interact with others in the community and experience a sense of belonging, as evidenced by the GIW-12P of creating a safe learning environment. Participants provided examples of practice that created a safe learning environment, including the Wellbeing, Relationships, Agency, and Personal Responsibility (WRAP) curriculum; individual plans in place to support learners with challenging needs; transparent, open and respectful ongoing communication with parents; parent and family involvement in multiple aspects of the school; school and system data that regularly surfaced how student and staff feel about their safety at the school; the development of pro-social school values; activation of student voice; and ongoing monitoring of student progress. Focus group and survey participants also acknowledged that wrap-around support provided to staff and students supported their work and provided high-quality student support.

Connected to the concept of wrap-around support and through further exploration of the GIW-12P pathway – positive family and community partnership, the survey invited participants to explore their relationships with families. All participants felt they had good relationships with students but reported that some parents and families sometimes did not treat staff respectfully. The GIW-12P enabled further reflective conversations in the focus groups by participants, whereby participants felt that their voice was heard within the community and that consultation, collaboration, and partnership with leadership were key drivers to successful relationships. Focus group participants outlined several practices that promoted positive educational-family and educational-community relationships. These included collaborating with families regarding learning plans, collaborating with families around wellbeing and learning, and participating in and celebrating spiritual ceremonies, parent nights, and the annual parent survey. Interestingly, participants in the focus group reported that the parents not very involved with decision-making or in their child’s learning achievements (“those not involved in following up on homework, attending parent interviews or information nights”) were more likely to express, often in what was perceived to be a rude manner, dissatisfaction with the teacher. These surfaced participants indicated a lack of respect (“being yelled at” or “spoken to rudely”) as negatively impacting their wellbeing.

These findings align with Mapp and Kuttner (Citation2013) research, which highlighted the correlation between parental involvement in education and various student outcomes, including achievement, grades, school attendance, learning efficacy, and the value students place on their education.

As a tool, the GIW-12P enabled the school context to demonstrate and celebrate their mutual understanding and shared language of wellbeing promotion within the community. It also enabled participants to surface what needs to be put in place to support teachers and school staff within their work with students and families to promote teacher wellbeing.

Outcomes from Using GIW-12P with the School Community

Through a process of reflective and collaborative practice undertaken through iterations of the survey and focus groups, the GIW-12P enabled school leadership to identify the importance of school communities being multidisciplinary and explore how they use the data to identify the practices, behaviors, artifacts, discourses and processes the staff (principal, school leadership, teachers, and social workers) undertake and engage in that promotes teacher and student wellbeing, therefore, creating a shared vision and shared focus. It provides a lens through which to explore what areas can be promoted, what activities might be culled, and how best to align human and financial resources.

Identified within the survey, all participants responded yes to the question, “I feel that school leaders commit to promoting the wellbeing of students and staff.” Participants described examples of the GIW-12P pathway of expert school leadership that focused on promoting wellbeing. Examples of expert school leadership included explicit and deliberate schoolwide wellbeing policies and procedures, a whole of-school wellbeing framework, a wellbeing curriculum, sharing of staff and student wellbeing data, and professional wellbeing staff to assist in delivering classroom-based wellbeing programs. Additionally, within the focus group, school leadership participants also surfaced that the school’s leadership team deliberately ensured that the school’s policies and procedures were intentionally and methodically connected to ensure that the school’s values, strategic direction, and wellbeing philosophies were central to all the school’s policies and practices. The finding also revealed that the pathway of expert school leadership within wellbeing explicitly linked the strategic visioning of wellbeing promotion within the community.

Participants provided evidence of strategic visioning of wellbeing promotion at the principal level (“the strategic plan is captured within is the school wellbeing framework”), middle leadership level (“the plan used to implement the Wellbeing, Relationships, Agency, and Personal Responsibility (WRAP) curriculum”), and the classroom teacher level where “strategies outlined in the plan can be seen to be implemented and evidenced in minutes from inclusion collaboration meetings and classroom plans.” In the survey, all participants agreed with the question: “I feel that the school community has a clear strategic vision for wellbeing.” In the focus groups, participants provided examples of artifacts where wellbeing was enacted in practice and was strategically aligned throughout the whole school campus. Participant examples of strategic visioning included “the Wellbeing, Relationships, Agency, and Personal Responsibility curriculum, wellbeing being valued, wellbeing framework, the school’s restorative practices program, schoolwide wellbeing data, and the language of wellbeing used within the school community.” GIW-12P tool enabled essential reflective and collaborative practice to surface the connection between expert school leadership, strategic visioning, evidence of practice, and the promotion of wellbeing.

Summary

Findings from the study surfaced an understanding of how educators promoted the wellbeing of students and staff in educational settings, in addition to what informed judgments around what effectual wellbeing promotion and practices were. Exploration of evidence of wellbeing practices within the school community aligned with what the school context was doing to promote wellbeing and support, care for and be inclusive of all staff and students.Three key themes emerged from the study. Firstly, how the GIW-12P can be used as a tool to identify wellbeing promotion. Secondly, how GIW-12P can be used. Thirdly, how the GIW-12P can be used to identify outcomes for a school community. Results from the study also evidenced a strong alignment with the Growing Inclusive Wellbeing through 12 Pathways (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023). wellbeing promotion model. Evidence of leadership that enabled wellbeing promotion, was also evident whereby the twelve key pathways informed the leadership of effective wellbeing promotion within the educational context. This study translates the theoretical GIW-12P model (Carter & Andersen, Citation2023) into practice, effectively guiding the leadership of wellbeing promotion within an educational context. Thus, this study provided a lens by which wellbeing could be theoretically and practically examined in a school, and evidence of the leadership of wellbeing promotion could surface.

Insights

Firstly, the GIW-12P model is a useful tool. The study surfaced the potential usefulness of the GIW-12P model as an investigative tool for illuminating areas where wellbeing promotion is effective while providing clear information regarding opportunities to enhance it further. The research-informed model presented easy-to-follow, clear pathways for promoting wellbeing aligned with the construct of wellbeing. Secondly, the use of the GIW-12P model offers an opportunity for participation from the whole school. The GIW-12P model supported leaders in the school to investigate wellbeing promotion. It required the school community to find evidence to justify that the explicit construct of wellbeing was promoted. The tool scaffolded a collaborative exploration of a shared understanding of the construct of wellbeing and how wellbeing is evidenced in the community in multiple ways (i.e., pathways). Employing the GIW-12P model offered opportunities for discussions that surfaced the connection between strategic leadership, evidence of practice, and the promotion of wellbeing across all areas of a large school (i.e., Preparatory to year 12). Thirdly, applying the model to the context resulted in a changed mind-set for participants, whereas evidence-based practice was fore-fronted in the application of wellbeing promotion. The concept of wellbeing moved from “ambiguity to clarity” for participants who used the tool.

Recommendations

Two key recommendations arise from this study.

The GIW-12P model should be supplied to all schools with a guide on how it can be implemented to facilitate the promotion of wellbeing. This study clearly showed that using the GIW-12P model as an investigative tool supports school leaders to promote wellbeing.

Further research is required in multiple educational contexts to evaluate the effectiveness of using the GIW-12P as a tool to promote wellbeing over time. The data within this research demonstrates how family and community partnerships can enable student wellbeing and how they impact teacher wellbeing. This, alongside the broader literature, suggests a significant benefit to these partnerships. Further research is needed to understand the practices, policies, and programs needed to support teachers and school staff in working with families to promote teacher wellbeing.

Further investigation should occur into the role of feedback and coaching in enhancing teacher wellbeing as in this study coaching conversations were reported as promoting wellbeing. Data from this research demonstrates that overall life satisfaction (i.e., a key component of wellbeing) is facilitated through collaboration with others and enhanced through coaching processes in this educational context.

Limitations

The major limitation that affects the study is the generalizability of results. Concentrating on an in-depth investigation solely in one large Catholic p-12 girls school site may limit the wider generalizability of findings to other school configurations and demographics. Data collection within a single organizational context necessarily restricts transferability (Peel, Citation2020). The researcher acknowledges that conclusions may differ when evaluating model effectiveness under alternate leadership structures, student backgrounds, and resources. Further research using the model is also required to investigate the transferability of the GIW-12P to larger school sites.

Conclusion

This research investigated how the GIW-12P model can inform the leadership of effectual wellbeing promotion within an educational context. Results surfaced that the GIW-12P was a helpful tool in supporting school leaders in identifying practices that promoted teacher and student wellbeing. Through the use of the GIW-12P, participants developed new knowledge regarding the use of human and financial resources. This, in turn, informed further decision-making to ensure investment was targeted at effectual wellbeing promotion. Understanding wellbeing promotion across educational settings allows school systems to work more effectively. GIW-12P is a useful tool to identify the practices, behaviors, artifacts, discourses, and processes that the principal, school leadership team, teachers, and social workers use to promote teacher and student wellbeing. The GIW-12P provides a common language for wellbeing promotion within the community and enables opportunities for professional learning and collaboration to occur more effectively for student and teacher wellbeing. These findings are important as they contribute to the literature on effectual wellbeing promotion.

Credit Statements

Jo Cains:

designed the study;

performed the investigation;

analysed and interpreted the data;

contributed materials, analysis tools or data;

co-wrote the paper.

Susan Carter:

guided the study;

guided the investigation;

critically guided reflection on the analysis and interpretation of the data;

co-wrote the paper;

critically reviewed the paper.

Cecily Andersen:

Co-wrote the paper;

critically reviewed the paper.

Ethical Statement

Wellbeing in Education Contexts (H19REA269).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Research data is unavailable for access as it is confidential. The data is stored in alignment with ethical standards.

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2017). Reflection and reflexivity in practice versus in theory: Challenges of conceptualisation, complexity, and competence. Educational Psychologist, 52(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1350181

- Australian Government. (2020). Australian student wellbeing framework. https://studentwellbeinghub.edu.au/educators/framework/

- Billett, P., Turner, K., & Li, X. (2023). Australian teacher stress, well‐being, self‐efficacy, and safety during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychology in the Schools, 60(5), 1394–1414. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22713

- Brennan, N., Beames, J. R., Kos, A., Reily, N., Connell, C., & Hall, S. (2021). Psychological distress in young people in Australia. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-09/apo-nid313947.pdf

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Ecological systems theory. In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 106–173). Sage Publications.

- Brunzell, T., Waters, L., & Stokes, H. (2015). Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: A new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000048

- Buric, A., Sliskovic, Z., & Penezic, Z. (2019). Understanding teacher wellbeing: A cross-lagged analysis of burnout, negative student-related emotions, psychopathological symptoms, and resilience. Educational Psychology, 39(9), 1136–1155. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1577952

- Carslake, T., & Dix, K. (2020). Wellbeing systematic review impact map and evidence gap map. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/well_being/16

- Carter, S. (2020). Case study method and research design: Flexibility or availability for the novice researcher? In H. van Rensburg & S. O’Neill (Eds.), Inclusive theory and practice in special education (pp. 301–326). IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-7998-2901-0.ch015

- Carter, S., & Abawi, L. A. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special & Inclusive Education, 42(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

- Carter, S., & Andersen, C. (2019). Wellbeing in educational contexts (1st ed.). The University of Southern Queensland. https://usq.pressbooks.pub/wellbeingineducationalcontexts/

- Carter, S., & Andersen, C. (2023). Wellbeing in educational contexts (2nd ed.). University of Southern Queensland. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3146661969/view

- Carter, S., Andersen, C., Turner, M., & Gaunt, L. (2023). “What about us?” Wellbeing of higher education librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 49(1), 102619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102619

- Clarke, A. M., Sixsmith, J., & Barry, M. M. (2015). Evaluating the implementation of an emotional wellbeing programme for primary school children using participatory approaches. Health Education Journal, 74(5), 578–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896914553133

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Crenguța, M. M., Bumbuc, S., & Martinescu-Bădălan, F. (2023). Personality traits, role ambiguity, and relational competence as predictors for teacher subjective wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1106892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1106892

- Das, K. V., Jones-Harrell, C., Fan, Y., Ramaswami, A., Orlove, B., & Botchwey, N. (2020). Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Reviews, 41(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00142-5

- De Souza, M. (2009). Promoting wholeness and wellbeing in education: Exploring aspects of the spiritual dimension. In M. D. Souza, L. J. Francis, J. O’Higgins-Norman, & D. Scott (Eds.), International handbook of education for spirituality, care and wellbeing (pp. 677–692). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9018-9_36

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective wellbeing. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

- Diener, E. (Ed.). (2009). Subjective Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being (Vol. 37, pp. 11–58). Social Indicators Research Series. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2350-6_2

- Eckersley, R. M. (2007). Culture, spirituality, religion, and health: Looking at the big picture. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(10), S54–S56. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01042.x

- Education & Solidarity Network. (2021). International barometer of the health and wellbeing of education personnel. https://www.educationsolidarite.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RES-FESP-Baro-Info-EN-2021.pdf

- Eid, M., & Larsen, R. J. (2008). Ed Diener and the science of subjective wellbeing. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective wellbeing (pp. 1–13). Guilford Press.

- Fraillon, J. (2004). Measuring student wellbeing in the context of Australian schooling: A discussion paper. Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs Curriculum Corporation. https://research.acer.edu.au/well_being/8

- Fray, L., Jaremus, F., Gore, J., Miller, A., & Harris, J. (2023). Under pressure and overlooked: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in NSW public schools. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(3), 701–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00518-3

- Govorova, E., Benítez, I., & Muñiz, J. (2020). How schools affect student well-being: A cross-cultural approach in 35 OECD countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 507738. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00431

- Grieves, V. (2007). Indigenous wellbeing: A framework for governments’ aboriginal cultural heritage activities. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/cultureheritage/GrievesReport2006.pdf

- Harding, S., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., Tilling, K., Evans, R., Bell, S., Grey, J., Brockman, R., Campbell, R., Araya, R., Murphy, S., & Kidger, J. (2019). Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080

- Huang, D., Wang, J., Fang, H., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., & Cao, S. (2022). Global research trends in the subjective wellbeing of older adults from 2002 to 2021: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 972515. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.972515

- Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

- Maggino, F., & Alaimo, L. S. (2021). Complexity and wellbeing: Measurement and analysis. In L. Bruni, A. Smerille, & D. D. Rosa (Eds.), Modern guide to the economics of happiness (pp. 113–128). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mahoney, J. L., Weissberg, R. P., Greenberg, M. T., Dusenbury, L., Jagers, R. J., Niemi, K., Schlinger, M., Schlund, J., Shriver, T. P., VanAusdal, K., & Yoder, N. (2021). Systemic social and emotional learning: Promoting educational success for all preschool to high school students. American Psychologist, 76(7), 1128. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000701

- Mapp, K., & Kuttner, P. (2013). Partners in education: A dual capacity-building framework for family-school partnerships. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory American Institutes for Research. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/family-community/partners-education.pdf

- McCallum, F. (2021). Teacher and staff wellbeing: Understanding the experiences of school staff. In M. L. Kern & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 715–740). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_28

- McCallum, F., & Price, D. (2016). Nurturing wellbeing development in education: From little things, big things grow. Routledge.

- Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Curriculum Corporation.

- Mission Australia. (2022). Annual youth survey 2022. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/what-we-do/research-impact-policy-advocacy/youth-survey

- Noble, T., McGrath, H., Wyatt, T., Carbines, R., & Robb, L. (2008). Scoping study into approaches to student wellbeing: Literature review. Report to the department of education, employment and workplace relations. https://www.dese.gov.au/student-resilience-and-wellbeing/resources/scoping-study-approaches-student-wellbeing-final-report

- Norwich, B., Moore, D., Stentiford, L., & Hall, D. (2022). A critical consideration of ‘mental health and wellbeing’ in education: Thinking about school aims in terms of wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 803–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3795

- Oberle, E., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2016). Stress contagion in the classroom? The link between classroom teacher burnout and morning cortisol in elementary school students. Social Science & Medicine, 159, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.031

- Olmos-Vega, F. M., Stalmeijer, R. E., Varpio, L., & Kahlke, R. (2023). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide No. 149. Medical Teacher, 45(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

- Peel, K. (2020). A beginner’s guide to applied educational research using thematic aaalysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 25(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.7275/ryr5-k983

- Powell, M. A., & Graham, A. (2017a). Reframing ‘wellbeing’ in schools: The potential of recognition. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(4), 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1192104

- Powell, M. A., & Graham, A. (2017b). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy–practice nexus. Australian Education Researcher, 44(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7

- Rubin, H., & Rubin, I. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing. Free Press.

- Soutter, A. K. (2011). What can we learn about wellbeing in school? Journal of Student Wellbeing, 5(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.21913/JSW.v5i1.729

- Thomas, H. M., Runions, K. C., Lester, L., Lombardi, K., Epstein, M., Mandzufas, J., & Cross, D. (2022). Western Australian adolescent emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 16(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00433-y

- Timperley, H. (2015). Professional conversations and improvement-focused feedback. A review of the research literature and the impact on practice and student outcomes. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/professional-conversations-literature-review-oct-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=fc2ec3c_

- White, M. A., & McCallum, F. (2020). Responding to teacher quality through an evidence-informed wellbeing framework for initial teacher education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4124-7_7

- White, R., & Wyn, J. (2013). Youth and society (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.