ABSTRACT

The paper concerns the development of digitally-mediated technologies that value social cooperation as a common good rather than as a source of revenue and accumulation. The paper discusses the activities that shaped a European participatory design project which aims to develop a digital space that promotes and facilitates the ‘Commonfare’, a complementary approach to social welfare. The paper provides and discusses concrete examples of design artifacts to address a key question about the role of co- and participatory design in developing hybrid spaces that nurture sharing and autonomous cooperation: how can co-design practices promote alternatives to the commodification of digitally-mediated cooperation? The paper argues for a need to focus on relational, social, political and ethical values, and highlights the potential power of co- and participatory design processes to achieve this. In summary, the paper proposes that only by re-asserting the centrality of shared values and capacities, rather than individual needs or problems, co-design can reposition itself thereby encouraging autonomous cooperation.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, we have witnessed the rise of economic activities based on digital platforms. This phenomenon has attracted considerable research interest and has been referred to as platform capitalism (Srnicek Citation2016), the gig economy (Mulcahy Citation2016), sharing economies (Sundararajan Citation2016), collaborative consumption (Botsman and Rogers Citation2010), and common-based peer production (Benkler Citation2011). Each of these labels represent a different position on the spectrum from ‘exploiting digital connectivity for market-based goals’ to ‘creating alternatives to the capitalist economic model’. In this paper, we focus on the design of digitally-mediated technologies that value social cooperation as an emancipatory practice rather than a source of revenue.

Our contribution resonates with the attention given to cooperation in Information Technology (IT) design, be it in social informatics (Kling Citation2007), computer-supported cooperative work (CSCW – Schmidt Citation2011), human–computer interaction (HCI – DiSalvo and Le Dantec Citation2017), participatory design (PD – Robertson and Simonsen Citation2013), or value-sensitive design (VSD – Friedman and Kahn Citation2007). All these approaches propose that digital technologies reconfigure social cooperation and in some cases promote more democratic perspectives, being focused on ethical issues and on the risk of the exploitative affordances of technologies themselves (e.g. Ehn Citation2008; Friedman and Kahn Citation2007; Brown et al. Citation2019). One of the main differences between these approaches is in the relation established between the IT researcher/s and the people involved in technology design, development and use. Social informatics and CSCW focus primarily on (usually) ethnographic studies of work and of IT use and reconfiguration in practice. PD and VSD are interested in the direct involvement of people in the design phase. More specifically, VSD combines conceptual, empirical, and technical investigation to deliver technologies that include human values throughout the design process. The potential users are considered as subjects of the empirical investigation (Friedman and Kahn Citation2007). PD, differently, aims at the direct involvement of people from the beginning of the design process, allowing them to have a say on the artefact they are going to use (Robertson and Simonsen Citation2013). This also means that designers ‘take sides’ in relevant social conflicts, particularly in the conflict between labour and capital (Ehn Citation1992), by combining design and sociological studies of system development (e.g. UTOPIA Project Group Citation1981).

Building on PD, this paper focuses on the combination of socio-economic research and technology design, while maintaining a ‘value-sensitive’ attention to conceptual, empirical, and technical moves in design projects. The aim is to address the following question: How can co-design practices promote alternatives to the commodification of digitally-mediated cooperation? To do so, we first introduce an overview of platform capitalism as developed in critical social theory; second, we reflect on the implications of these readings for contemporary design practices, framing our contribution in the current debate in PD and HCI; then we present and discuss an empirical case, the Commonfare project, in which social research and system design have been aligned in the light of the presented understanding of capitalism and of design practices; finally, we discuss how co-design can be re-positioned in order to foster autonomous cooperation.

2. Understanding platform capitalism

Recent critical approaches to the political economy of digital media have emphasized the ways in which digital platforms operate in order to extract wealth from social cooperation, and to commodify the ‘common goods,’ intended as environmental/primary consumption resources and knowledge items (e.g. Harvey Citation2007). It is argued that social media platforms turn social interactions, forms of activism, and care for significant others into a source of economic value through the algorithmic quantification of human capacities which become commodities sold to advertisers (Van Dijck Citation2013; Fuchs Citation2013). From this perspective, digital technologies become crucial in turning lives, affects, and relations into commodities, to the benefit of some of the wealthiest corporations in the world.

The extraction of economic value from shared resources has pushed some commentators to describe the time we are living in as characterized by a new ‘mode of production’, called ‘the common’, that is the constructed ensemble of material and symbolic resources tying together human beings (Hardt and Negri Citation2009). In the common mode of production, human work and cooperative practices are central (Vercellone Citation2015). The capacity of contemporary capitalism to turn the common into a source of value has led to the proposal of a ‘life theory of value’ (Morini and Fumagalli Citation2010), in which life – human, animal, and nature – is the basic element put to work for capital accumulation. The concept of cooperation that is central in social informatics, CSCW, and PD becomes the defining trait of contemporary political economy in the digital world, and it is where the contradictions of the current mode of production are visible and in the making. For designers, this becomes a contradiction to inhabit (Teli Citation2015).

The contradiction stands, philosophically, in what already Karl Marx identified in his idea that the capacity to work and to cooperate preexists the organization of work and cooperation by capital (Marx Citation1887), and the relation between cooperation and capital is historically determined. The school of thought of Autonomous Marxism has discussed the relation between cooperation and capital as one in which cooperation is a driving force in social change and capital constantly tries to discipline cooperation itself (e.g. Hardt and Negri Citation2009; Negri and Tronti Citation2016). Referring to autonomous cooperation we refer, then, to forms of cooperation that have not (yet?) been disciplined by capital and that can point to forms of social change. In platform capitalism, capital disciplines cooperation via the commodification of social interactions and common goods that are incorporated in many contemporary ICT tools (e.g. dating apps, but also mental health support platforms, see Brown et al. Citation2019). This reality reflects an often unarticulated and thus unchallenged alignment with capital accumulation, which highlights the increasing relevance of digitally manipulated data for exploitation and generation of financial profit (Srnicek Citation2016). Designers are deeply implicated in this process, as companies refine their technologies to augment the profitability of their platforms, but designers can also engage critically with the same process, as in the cases of the platform cooperativism movement (Scholz Citation2016) or the commons-transition project (Troncoso and Utratel Citation2015).

3. Design practices as a field of struggle

Looking at the design of digital technologies, participatory- and co-design in particular, we see efforts to problematize the alignment with capital accumulation and advance alternative approaches (e.g. Hakken, Teli, and Andrews Citation2016; Light and Akama Citation2014). In all these cases, the actions of designers are constrained by, and in relation with, existing institutional forms (Huybrechts, Benesch, and Geib Citation2017). Therefore, in the attempt to promote new institutional configurations (e.g. Teli, Di Fiore, and D’Andrea Citation2017), these efforts cannot avoid situating themselves in the midst of the contradictions of the current social configurations, envisioning potential futures starting from the material conditions of the people involved in co-design activities (Sciannamblo, Lyle, and Teli Citation2018).

The way co-design can operate in the actual conditions is closer to the embeddedness of the designer in social movements (e.g. Vlachokyriakos et al. Citation2018) than to approaches like VSD, in which all the stakeholders’ values are mapped and put at play, and ontological inquiries help solving conflicts among the different values. In other words, we propose a materialistic approach to co-design, siding with those social groups who are already experimenting with alternatives-to-the-current-model based on care, reciprocity, and solidarity, rather than on a liberal approach accommodating also the perspectives of the powerful ones.

A significant challenge of designing digital platforms which confront the status quo and contribute to the establishment of alternative economic foundations is reaching critical mass beyond the locality of a co-design intervention (e.g. Frauenberger, Foth, and Fitzpatrick Citation2018). Teli et al. (Citation2015) and Le Dantec (Citation2016) refer to this scaling-up process as the formation of publics (Le Dantec and DiSalvo Citation2013), i.e. heterogeneous groups of people who are concerned about issues present in their daily life that become socially recognized as ‘matters of concern’ (Latour Citation2004) around which people organize themselves to intervene (Le Dantec Citation2016). The relation between the issue at stake and the people involved can be defined as an attachment, a relation of dependency or commitment that is simultaneously material, affective, and societal (Marres Citation2007). In this sense, the concept of matters of concern is not only a lens of interpretation of ongoing projects but also a practical instrument for collaborative design (Poderi et al. Citation2018). The application of ‘public design’ requires methods and techniques able to influence relations and attachments and to recursively prompt collective actions to address the issues which bring different people together (Teli et al. Citation2015). The substantial expertise accumulated in the last twenty years in PD projects (Ehn Citation2008; Bødker et al. Citation2000) can provide a distinct perspective to leverage public design in practice. Yet, when PD is applied in the public realm, several issues emerge relating to, for example, context, scale, and ethics (Dalsgaard Citation2010; De Angeli, Bordin, and Menendez-Blanco Citation2014). A truly democratic approach to public design requires engagement in PD to be scaled up from multiple perspectives (Cozza and De Angeli Citation2015). This implies not only increasing the number of participants, but also ensuring their heterogeneity, thereby having different voices contributing to solving issues with which people are concerned.

Public design faces important challenges with respect to ensuring that a variety of expectations created during the design process will be fulfilled and the inputs of participants respected and rewarded. Connecting this with the notion of ‘the common’ implies finding ways to work alongside local practices that nourish the common such as those based on solidarity economy (Vlachokyriakos et al. Citation2018). Moreover, despite important work which has studied the societal outcomes emerging from the appropriation of public design artifacts by people (Teli et al. Citation2015; Le Dantec and DiSalvo Citation2013; Light and Briggs Citation2017), less knowledge is available on how these artifacts should be designed in practice (Menendez-Blanco, De Angeli, and Teli Citation2017; De Angeli, Bordin, and Menendez-Blanco Citation2014).

The empirical case we present in the remaining of this paper, that is Commonfare, deals exactly with the collaboration between designers and people considered at risk of social exclusion to the aim of sustaining the latter in dealing with the issues with which they are concerned.

4. Method

The valorization of social cooperation as common good is at the heart of Commonfare, a project aiming to tackle important societal challenges such as precariousness, low income and unemployment. Its ultimate goal is to foster and facilitate the Commonfare, a new form of welfare based on rewarding social cooperation as practiced by grassroots initiatives and local communities committed to re-appropriating common goods (Fumagalli and Lucarelli Citation2015). The project falls within the politically-engaged tradition of PD, to create methods, tools and techniques in both research and design practices that value bottom-up cooperation (Robertson and Simonsen Citation2013). More specifically, it combines socio-economic research with the design of digital technologies in order to develop a digital space, commonfare.net, for people to: 1) find organized information about institutional welfare provisions, 2) share stories about bottom-up collaborative welfare practices; and 3) support the spreading and scaling-up of such practices, especially through networking tools able to sustain interaction and exchange among individuals and communities. Commonfare.net is being developed and piloted in three European countries – Croatia, Italy, and The Netherlands – and targets people that are considered by the EU to be at risk of material deprivation or social exclusion, such as young unemployed, precarious workers, welfare recipients, and non-European migrants (Eurostat Citation2016). To foster connections and to facilitate the flow of common goods and wealth such as information, affect and resources, commonfare.net includes a trust facilitation system (Commonshare) and a digital complementary currency (Commoncoin), plus the possibility for communities and groups to create their own digital currency (see also Huttunen and Joutsenvirta Citation2019).

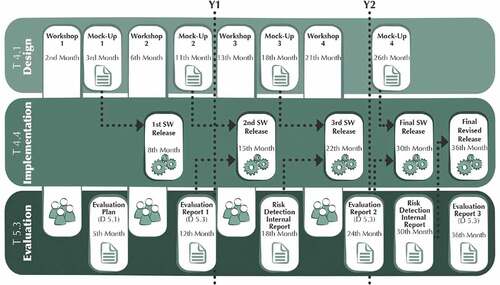

We built on the research and co-design activities conducted during the first 15 months of the project (July 2016 – October 2017) to define the socio-economic conditions and emerging needs of research participants in the pilot countries, and to inform the design of the main features of commonfare.net. These activities include interviews, workshops and focus groups involving around 250 people (Fumagalli et al. Citation2017; Wilson et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b – see ). These first 15 months of the project informed the high-level conceptual design of the whole digital space leading to the second release of commonfare.net, and to features appearing in the third and fourth release – namely, the digital currency and the trust facilitation system – (see for a schematic timeline).

Table 1. Reports, data and methods – Commonfare project, July 2016 – October 2017.

The data sources listed in were iteratively discussed and elaborated upon in several co-design meetings with research participants and in PD meetings involving all the project partners. Interview and focus group materials were read by several researchers and thematically analyzed following different approaches. All the authors of this paper had a key role in both the research and the design of the platform. They engaged both directly with participants and project partners, and indirectly with qualitative materials and design artefacts. In this paper we describe these rich set of data following the results of a thematic analysis based on values.

5. The emerging centrality of autonomous cooperation

The iterative interaction with research participants and artefacts soon brought us to realize the emerging centrality of what people involved in co-design activities regarded as important values, and the necessity for these values to be embedded in commonfare.net. Although we did not explicitly ask participants about their values, they repeatedly referred to them during different forms of engagement. As we illustrate in the following, such values range from autonomy, to dignity, to the recognition of one’s capacities, ultimately uncovering a desire for self-determination yet as members of social formations of some sort. People manifested the desire for a valued self within a valued community or network of social relationships.

5.1. From practical needs to relational values

One of the main concerns expressed by research participants relates to the practical needs of people in troubling financial conditions (such as precarious workers). These needs translate into demands for services that can facilitate the search for solutions to practical problems. As Javier, an Italian precarious worker in his thirties, puts it:

the most important service you could offer is to have a place where people [experiencing precarity] can access information on how to solve their problems.

The demand for practical advice addressing the needs of participants was somehow anticipated since the stage of project proposal, with the design of an ‘information hub’ providing updated and well-organized information about public benefits in the three pilot countries. What turned out to be novel was the relevance of relational values that goes beyond the manifestation of individual needs, like in the case of Filip, a Croatian unemployed man in his early thirties:

I’m not asking for much. Just a decent job with which I can afford to pay for housing and food, a little vacation time, and to be able to help my parents when the time comes how they helped me. I’m not looking for anything luxurious.

The claim for ‘not much’, just the condition (a decent job) to afford basic material needs (housing and food) and some immaterial needs (vacation time), is related to the desire of helping significant others – in this case, parents – thereby reciprocating the help and care received. This tendency to consider relational values as much as practical needs highlights the importance of immaterial shared goods (such as care for the family) and the neglect of rich material goods or ‘anything luxurious’. The call for dignity is clear in the words of Filip. Here dignity is framed as ‘decent’ material conditions coupled with the opportunity to cultivate one’s relationships with a satisfactory degree of reciprocity (cf. e.g. Gouldner Citation1960).

5.2. From relational to social values

The recognition of the importance of social relationships has become even clearer with research participants referring to common values as important to the successful creation of (online) cooperative communities. Giorgio, an Italian precarious freelancer, is quite explicit on this regard:

we need to build a tool that allows to create mechanisms for mutual solidarity among peers, among people that recognize the same framework of values.

Once tackling directly platform design, the relevance of relations goes beyond interpersonal relationships such as family ties or friendship, and is instead framed in social terms, oriented to public goods (Donati Citation2013). Therefore, intrinsically social values come to the forefront, being that solidarity, like in Giorgio’s case, or fairness, justice and equity, values that implicitly underlie the following comment by another precarious freelancer:

Digital platforms are often ruled by the strong/tough – how can commonfare.net support ‘the weak’? (anonymous response recorded on post-it notes during workshop activity in the Netherlands).

These claims uncover a desire to belong to a mutually supportive and cooperative community. Participants do not want a platform reproducing the same political economic process that have marginalized them in the first place: instead, they seek a space in which they could develop their self- and communal worth. As another Italian precarious worker highlighted,

the most important thing for the precarious worker who is surrendering and feel disenfranchised is to be able to see him/herself [in others]. Because s/he is alone, and risks getting lost as s/he is reduced to a function in society, dehumanized.

This excerpt shows that the value of a community sharing a common set of values and a common culture is not only a social value, a public good, but also a value for the individual belonging to the community. In other words, the way to get out of a condition of loneliness and isolation that many precarious workers experience relies on the recognition and valuing of similar experiences. Such mutual recognition is relevant insofar as it allows people experiencing precariousness to open up about their feelings and frustrations, liberating themselves from the sense of guilt that the neoliberal rhetoric of ‘poor-shaming’ instills. In so doing, on the other hand, mutual recognition holds the potential to weaken such a rhetoric itself.

5.3. Empowering individuals by nurturing their community

This twofold potential – liberating the individual and weakening the rhetoric – is particularly important given the relevance attributed to dignity and autonomy by participants, as the following excerpts show:

I am very proud of my family, as we have always lived with dignity (Precarious worker, Italy, male, 20–29).

[I’m] proud to have had the courage to listen to the heart and stop a job, losing €3000 per month, to stay happy … it was a very difficult decision because I had nothing, but I managed it … it was a decision of path (Precarious worker, Netherlands, female, 40–49).

Such a desire to maintain one’s own self-worth and dignity beyond material richness, despite exclusion and marginalization, pairs with the condemnation of the shaming culture thrown against public benefit recipients. As a freelancer who had been seeking a public subsidy for her arts-based work in the Netherlands puts it:

I felt horrible. You need to be homeless, disabled, in debt. I can work. It was damaging to dignity. I had thought it was a subsidy, but I felt embarrassed to be there.

The deprecation of any attempt to damage one’s own self-worth and dignity runs in parallel to the sense that Commonfare participants would be contributing to the common strength and to the value of a community, or better of several ones, both co-present and distributed. For instance, participants to a design workshop run in the Netherlands with freelancers of the creative sector envisioned commonfare.net as a digital space where they would be doing ‘something I really love, and I’m really good at’ and where it is important ‘feeling that by participating, you are a part of something beautiful!’. This supported findings from the interviews and focus groups (Fumagalli et al. Citation2017; Wilson et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b) that contributing to the common strength of a community is critical, both per se, as a social value, and in the(ir) concept(ualization) of self-determination itself.

6. Designing for autonomous cooperation

In this section we highlight how the design of commonfare.net (Bassetti et al. Citation2018) reflects the desire of autonomy and dignity both for oneself and one’s community (physical and/or digital). It reflects the previous section from relational needs to social values, and the empowerment of individuals to nurture and via nurturing their communities. The design of commonfare.net as part of a co-design process has sought to allow for reflection among all participants, to incorporate changes.

6.1. Designing for needs

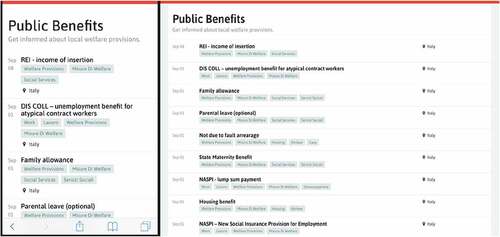

The design of commonfare.net reflects people’s needs by providing information about public benefits. Access to and use of information about available welfare measures seeks to respond to participants needs, and doing so on a digital platform where the information can be interacted with (through sharing and commenting). The design of a public benefits section focused on accessibility, in the sense that they would be able to

be used effectively on different platforms (mobile and desktop) and in different languages (English plus the mother tongue language for all benefits); moreover, the benefits have been (re)written following a common schematic format and in the least bureaucratic and most comprehensible way possible (e.g. avoiding legalese). A screenshot of the public benefits currently on commonfare.net is shown in .

6.2. Designing for relational values

The design of commonfare.net reflects the desire for people to connect with one another for mutual recognition and solidarity among peers. This was realized through the ability (a) to create and share stories of individual and collective experiences, (b) to create groups around shared interests, and (c) to communicate directly between commonfare.net participants with private messaging. The creation and sharing of stories was intended to nurture ‘mechanisms for mutual solidarity’ (cf. Section 5.1), and to allow for contributing to/with ‘something beautiful’ (cf. Section 5.3). One way in which the process of constructing a story attempts to express this is with the use of different building blocks (for different types of media, e.g. headings, text, images, video) to enable the ease of creating beautiful stories. A screenshot of the list of stories, alongside the creation process (showing some of the different elements that can be used within the ‘storybuilder’ tool) is presented in . Besides the related engagement potential, multimedia content was thought of as a way to increase accessibility by those less familiar with reading/writing.Footnote1 It is however true that commonfare.net storytelling tool does seem to suit better people with fair literacy and writing skills.

6.3. Designing for autonomy and dignity of both individuals and communities

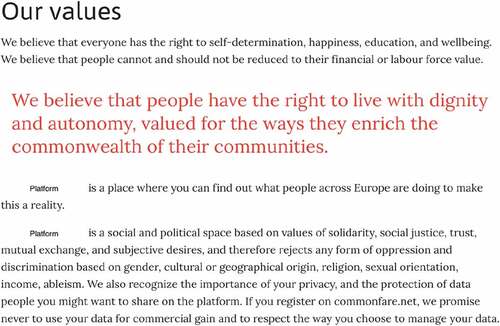

This section highlights how the creation of personas and scenarios based on the values and capacities of prospect commonfare.net participants constituted a central design tool for commonfare.net. As reported in Wilson et al. (Citation2017a), 6 personas and 9 scenarios, demonstrating the personas in action, were created to represent the diversity of sense of dignity and self-authorship over different aspects of people’s lives. Before providing some examples, let us notice that keeping values central to our design practice is not only visible in platform features and design tools such as personas and scenarios, but also and explicitly on the platform, in the ‘About’ section, as shown in .

One example of persona in its scenario is that of ‘Kas’ (). Kas is presented as a disempowered, downtrodden member of the underclass who may exploit commonfare.net to take control of his own story. Kas writes openly about his experiences of Dutch enforcement of welfare provision conditions on commonfare.net. His story triggers several sequences of events, some affecting Kas directly but others with the potential for much greater impact. The scenarios for Kas, for example, depict his Social Services case worker reads the story and decides to reassess Kas’s case – but she also starts to think about the unrecognized contributions and value to the community of other people not in formal paid work. Through the creation of new relationships and connections, Kas’s story also leads to employment law advice sessions being held in the local community centre, part of Commonfare’s hybrid space.

The scenarios pointed to a number of interactions that commonfare.net participants could have with each other. This provided direction for designers to consider when proposing interface and navigation elements (then used as a basis for feedback and further engagement with co-design participants). For instance, with respect to storytelling, the scenarios provided a sense of the diversity of stories that could be presented, and how a story could promote further interaction between participants (direct messaging, sharing the story with others).

The personas also highlighted the different levels of engagement to expect, and the importance of supporting people who do not wish to create an account on the platform, while still being able to engage with most content. Indeed, the relevance of autonomy and dignity also led us to focus on protecting the privacy of commonfare.net participants. Examples include allowing all content to be optionally posted anonymously (although requiring an account to do so), and not validating email addresses on account creation. These contributions are part of the larger impact that value-based personas and scenarios have had on the design process.

7. Conclusion

This paper has shown how co-design practices were aligned with social research and system design in order to promote alternatives to the commodification of social cooperation. This endeavor moved from technology design based on identifying users’ needs to the recognition of participants’ values – in particular, common values including dignity, freedom, autonomy, and self-authorship. Our recursive interaction and work with research participants have uncovered the importance of not only practical needs, both material (e.g. housing, food) and immaterial (e.g. information), but also, and more significantly, the care for relational values (e.g. helping significant others) and social values (e.g. solidarity, equity, recognition of people’s worth). Taken all together, these values contribute to building the dignity and autonomy of individuals and their communities, in a virtuous cycle of mutual empowerment.

The need for basic information as well as the desire to connect with others have been reflected in the design of commonfare.net, via the public benefits section, and a ‘storybuilder’ that allows creating and sharing stories of both individual and collective experiences. More generally, personas and scenarios built as valuing dignity and autonomy of research participants constituted the basis for several design activities as the main design tool able to embed participants’ values.

Our perspective is consistent with the emerging view that platform design should reject approaches devoted to exploitation and commodification of digitally-mediated cooperation (Srnicek Citation2016). Accordingly, we propose a co-design approach valuing not only the involvement of people, but also and especially their knowledge, competence, values and relationships. This approach may support cooperative practices capable of establishing the common as a mode of production (Vercellone Citation2015). This possibility directs us to view a platform as a space in which social cooperation emerges autonomously, rather than as a system that offers solutions or fulfils users’ needs. This suggests that design should focus on creating potential connections, channels along which common resources such as information, practices, and common values can flow, as well as facilitating the sharing of concrete resources and time in the physical world. Accordingly, the approach informing the design of commonfare.net has been devoted to co-designing and re-imagining ongoing future societal relations based on sustainable and democratic values, beyond the immediacy of developing a material artifact with its own limits and finiteness (Light and Akama Citation2014).

In discussing how co-design can be repositioned in order to promote alternatives to the digitally-mediated commodification of social cooperation, we have showed how public design artifacts can be designed and developed in practice (Menendez-Blanco, De Angeli, and Teli Citation2017; De Angeli, Bordin, and Menendez-Blanco Citation2014). The sharing of individual and collective stories that emphasizes the significance of social values and the re-appropriation of common goods by research participants have also pointed out how public design can find ways to work alongside local practices that nourish the common, such as those based on solidarity economy (Vlachokyriakos et al. Citation2018).

It is in engaging with these experiences that design practices in general, and co-design practices in particular, might reposition themselves. Design processes that lead to systems, spaces and artefacts that embody and facilitate social values is key to avoid the currently dominant, market-based and individualistic model of platform capitalism. Our work on commonfare.net suggests that a way to achieve this is by re-establishing the centrality of values and capacities, thereby respecting and rewarding participation in the design process, fulfilling expectations, while listening to a polyphony of voices. This approach is also consonant with political economic perspectives that value community and social cooperation, since these can be formed through recognition of shared values and the mutual respect that comes with focusing on people’s knowledge and capacities rather than their needs or alleged lacks (Hakken, Teli, and Andrews Citation2016). In adopting this approach, we make it more likely to create a platform which embodies the ethos and values of those that would transform it from a platform to a space of commoning (Federici Citation2018; Fumagalli and Lucarelli Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The possibility to include also a read-aloud feature has been considered but not yet implemented due to other project constraints.

References

- Bassetti, C., A. De Angeli, M. Jovanovic, P. Lyle, G. Monaco, D. Rough, and M. Teli. 2018. Interface Mockups (I, II, III, IV). http://pieproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/D4.1-Final.pdf

- Benkler, Y. 2011. The Penguin and the Leviathan: How Cooperation Triumphs over Self-Interest. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group.

- Bødker, S., P. Ehn, D. Sjögren, and Y. Sundblad. 2000. “Co-Operative Design—Perspectives on 20 Years with ‘the Scandinavian IT Design Model’.” In Proceedings of NordiCHI, 2000, 22–24. Stockholm, Sweden: Royal Institute of Technology.

- Botsman, R., and R. Rogers. 2010. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Brown, A. V., J. H.-J. Choi, and J. Shakespeare-Finch. 2019. “Care Towards Posttraumatic Growth in the Era of Digital Economy.” CoDesign 15 (3): 212–227. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631350

- Cozza, M., and A. De Angeli. 2015. “Scaling up Participatory Design”. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Socio-Technical Perspective in IS Development (STPIS’15) co-located with the 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering (CAiSE 2015), Stockholm, Sweden, 106–113.

- Dalsgaard, P. 2010. “Challenges of Participation in Large-Scale Public Projects.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 21–30. New York, NY: ACM.

- De Angeli, A., S. Bordin, and M. Menendez-Blanco. 2014. “Infrastructuring Participatory Development in Information Technology.” In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference: Research Papers - Volume 1, 11–20. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/2661435.2661448.

- DiSalvo, C., and C. A. Le Dantec. 2017. “Civic Design.” Interactions 24 (6): 66–69. doi:10.1145/3137097.

- Donati, P. 2013. “The Added Value of Social Relations.” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 5: 1.

- Ehn, P. 1992. “Scandinavian Design: On Participation and Skill.” In Usability, edited by P. S. Adler and T. A. Winograd, 96–132. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc.

- Ehn, P. 2008. “Participation in Design Things.” In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008, 92–101. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1795234.1795248

- Eurostat. 2016. People at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion - Statistics Explained. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/People_at_risk_of_poverty_or_social_exclusion

- Federici, S. 2018. Reincantare Il Mondo. Femminismo E Politica Dei Commons. Verona, Italy: Ombre Corte.

- Frauenberger, C., M. Foth, and G. Fitzpatrick. “On Scale, Dialectics, and Affect: Pathways for Proliferating Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference (PDC) 2018. Hasselt and Genk, Belgium: ACM.

- Friedman, B., and P. H. Kahn Jr. 2007. “Human Values, Ethics, and Design.” In The Human-computer Interaction Handbook, edited by A. Sears, J. A. Jacko, J. A. Jacko, 1223–1248. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429163975

- Fuchs, C. 2013. Digital Labour and Karl Marx. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fumagalli, A., R. Serino, S. Gobetti, C. Morini, G. Allegri, L. Santini, D. Paes Leão, et al. 2017. PIE News - Research Report. http://pieproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/PIE_D2.1.pdf

- Fumagalli, A., and S. Lucarelli. 2015. “Finance, Austerity and Commonfare.” Theory, Culture & Society 32 (7–8): 51–65. doi:10.1177/0263276415597771.

- Gouldner, A. W. 1960. “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.” American Sociological Review 25: 161–178. doi:10.2307/2092623.

- Hakken, D., M. Teli, and B. Andrews. 2016. Beyond Capital: Values, Commons, Computing, and the Search for a Viable Future. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hardt, M., and A. Negri. 2009. Commonwealth. 1 ed. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York, NY: Oxford university press.

- Huttunen, J., and M. Joutsenvirta. 2019. “Monies, Economies and Democracy: Cultivating Ambivalence in the Co-design of Digital Currencies.” CoDesign 15 (3): 228–242. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631352

- Huybrechts, L., H. Benesch, and J. Geib. 2017. “Institutioning: Participatory Design, Co-Design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 148–159. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1355006.

- Kling, R. 2007. “What Is Social Informatics and Why Does It Matter?” The Information Society 23 (4): 205–220. doi:10.1080/01972240701441556.

- Latour, B. 2004. “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? from Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1086/421123.

- Le Dantec, C. A. 2016. Designing Publics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Le Dantec, C. A., and C. DiSalvo. 2013. “Infrastructuring and the Formation of Publics in Participatory Design.” Social Studies of Science 43 (2): 241–264. doi:10.1177/0306312712471581.

- Light, A., and J. Briggs. 2017. “Crowdfunding Platforms and the Design of Paying Publics.” In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 797–809. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/3025453.3025979.

- Light, A., and Y. Akama. 2014. “Structuring Future Social Relations: The Politics of Care in Participatory Practice.” In Proceedings of the 13th Participatory Design Conference. Research Papers-Volume 1. Windhoek, Namibia: ACM.

- Marres, N. 2007. “The Issues Deserve More Credit: Pragmatist Contributions to the Study of Public Involvement in Controversy.” Social Studies of Science 37 (5): 759–780. doi:10.1177/0306312706077367.

- Marx, K. 1887. “Capital: Volume One.” Moscow: Progress Publishers. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm

- Menendez-Blanco, M., A. De Angeli, and M. Teli. 2017. “Biography of a Design Project through the Lens of a Facebook Page.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 1–26. doi:10.1007/s10606-017-9270-4.

- Morini, C., and A. Fumagalli. 2010. “Life Put to Work: Towards a Life Theory of Value.” Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 10 (3/4): 234–252.

- Mulcahy, D. 2016. The Gig Economy: The Complete Guide to Getting Better Work, Taking More Time Off, and Financing the Life You Want. New York, NY: AMACOM.

- Negri, A., and M. Tronti 2016. Operai E Capitale: 50 Anni. http://www.euronomade.info/?p=7366

- Poderi, G., M. Bettega, A. Capaccioli, and V. D’Andrea. 2018. “Disentangling Participation through Time and Interaction Spaces–The Case of IT Design for Energy Demand Management.” CoDesign 14 (1): 45–59. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1416145.

- Robertson, T. J., and J. Simonsen. 2013. Participatory Design: An Introduction. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Schmidt, K. 2011. “The Concept of ‘work’in CSCW.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 20 (4–5): 341–401. doi:10.1007/s10606-011-9146-y.

- Scholz, T. 2016. Uberworked and Underpaid: How Workers are Disrupting the Digital Economy. Cambridge, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sciannamblo, M., P. Lyle, and M. Teli 2018. “Fostering Commonfare. Entanglements between Participatory Design and Feminism”. In Proceedings of DRS Design Research Society Conference, Vol. 2. Limerick, Ireland: University of Limerick. doi:10.21606/drs.2018.557

- Srnicek, N. 2016. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sundararajan, A. 2016. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Teli, M. 2015. “Computing and the Common. Hints of a New Utopia in Participatory Design.” Aarhus Series on Human Centered Computing 1 (1): 4. doi:10.7146/aahcc.v1i1.21318.

- Teli, M., A. Di Fiore, and V. D’Andrea. 2017. “Computing and the Common: A Case of Participatory Design with Think Tanks.” CoDesign 13 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1309439.

- Teli, M., S. Bordin, M. M. Blanco, G. Orabona, and A. De Angeli. 2015. “Public Design of Digital Commons in Urban Places: A Case Study.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, Transdisciplinary Approaches to Urban Computing 81 (Sep.): 17–30. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2015.02.003.

- Troncoso, S., and A. M. Utratel. 2015. Commons Transition: Policy Proposals for an Open Knowledge Commons Society. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Foundation for Peerto-Peer Alternatives.

- UTOPIA Project Group. 1981. The UTOPIA Project. On Training, Technology and Products Viewed from the Quality of Work Perspective. Stockholm, Sweden: Arbetlivscentrum.

- Van Dijck, J. 2013. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vercellone, C. 2015. “From the Crisis to the ‘welfare of the Common’ as a New Mode of Production.” Theory, Culture & Society 32 (7–8): 85–99. doi:10.1177/0263276415597770.

- Vlachokyriakos, V., C. Crivellaro, P. Wright, and P. Olivier. 2018. “Infrastructuring the Solidarity Economy: Unpacking Strategies and Tactics in Designing Social Innovation.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 481. 1–481:12. New York, NY: ACM. doi:10.1145/3173574.3174055.

- Wilson, A., M. Sachy, S. Ottaviano, F. De Pellegrini, and S. De Paoli 2017a. PIE News - User Research Report and Scenarios. http://pieproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/PIE_D3.1_FIN.pdf

- Wilson, A., M. Sachy, S. Ottaviano, F. De Pellegrini, and S. De Paoli 2017b. Reputation Mechanics, Digital Currency Model and Network Dynamics and Algorithms. http://pieproject.eu/2017/10/02/d3-2-reputation-mechanics-digital-currency-models-and-network-dynamics-and-algorithms/