ABSTRACT

Co-design aims to bring designers and end-users together to improve the quality of design projects. In this paper, we study how the distance between designers and users can be reduced with an empathic approach particularly in settings where it is significant. By investigating various approaches on empathy in design and architecture, we were able to retrospectively understand different aspects of the design process of a maternity ward project in which we were involved. Engaging a theoretical clarification of empathy as a multi-dimensional concept made it possible to empirically explicate diverse difficulties that designers face when trying to employ empathy as a guiding philosophy in their work. As a result, we identified three registers of empathy on a varying scale of depth that can be integrated in the design process. Our work shows that various registers of empathy can complement each other or be utilised in different circumstances where one form might be more appropriate than another. By presenting these registers, we seek to unbox the different views on empathy and draw attention to the potential of empathic engagement when aiming for depth in a project.

1. Introduction

A central theme in co-design is the relation between designer and user. Our research focuses on this relation concerning the ‘distance’ between designer and user and how this distance can be reduced to create ‘depth’ in the design process.

The distance between stakeholders has posed a general challenge since the beginning of participatory design. It originates in the concept of ‘workplace democracy’ – reducing the distance between people from different levels of organisational hierarchies and giving them an equal say (Gregory Citation2003). When designers work within the public realm (and with diverse stakeholders), this inequality is even more complex (Keshavarz and Maze Citation2013). Particularly in humanitarian design, in low-income countries, or when users are in a vulnerable situation – which is the field in which we work – there is often a distant relation between actors. Distance between actors in challenging settings has been addressed in design research through for instance case studies on designing for children with disabilities in Cambodia (Hussain and Sanders Citation2012; Hussain, Sanders, and Steinert Citation2012), mourners (Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout Citation2016), and patients with dementia (Smeenk, Sturm, and Eggen Citation2018).

Empathy can be one way to reduce distance and deepen the design process. We refer here to empathy broadly as experiencing and appraising the world from another’s point of view and as a quality of social encounters. Since designers and architects seldom design for themselves, and their designs often affect several people, we assert that empathy ought to be one of their core professional competencies. Therefore, professionals in these fields would benefit from better understanding the multi-dimensional nature of empathy.

This led us to study how the concept of empathy has been used in design and architecture. In the study we encountered a variety of approaches that separated the view on empathy into ‘boxes’ apparently unaware of their respective content. In the architecture literature, empathy is discussed as a phenomenological approach through architects’ personal experience when they imagine themselves as users (Pallasmaa Citation2015). In design discourse, ‘empathic design’ (Koskinen and Battarbee Citation2003) is presented as a practical toolbox to support the endeavour of understanding users with empathy (Sanders and Stappers Citation2014). In recent literature on empathic design, there is an emphasis on sensitivity, particularly when dealing with vulnerable users (Mattelmäki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen Citation2014). There is also a call for using intimacy to create depth when designing for social innovation (Akama and Yee Citation2016).

Our interest in the depth of the relationship between designers and users is motivated by the evident challenges and opportunities we encountered when executing a maternal health design project for low-resource settings. We observed the types of social structures, entanglements, and cultural divergences that influence the distance between actors. The challenge of humanitarian co-design is not only to bridge the distance between stakeholders but also to increase the depth of the relations. In this paper, we aim to unbox the various forms of empathy and through that understand how and to what extent increased depth can be achieved.

We reflect retrospectively here on the different roles of empathy in a design project and share empirical examples from maternity ward design processes in Tanzania and India. Moreover, we enquire into differences, challenges, and conflicting situations regarding empathy when working in a heterogeneous environment with diverse stakeholders. Our retrospective reflection is carried out to synthesise and clarify the terminology related to empathy in design. We can identify three different registers of empathic engagement in real-world practice that can be in service of design and architecture research as well as of future projects of a similar type.

2. Designing with empathy

Within the design field, we found conflicting views on how empathy can bridge the distance between me (the designer) and the other (the user). In architecture research, the role of the architect is strong, and imagination is understood as a way of being empathically involved. In empathic design discourse, the main focus is on the user experience, and thus there is less emphasis on the role of the designer. These different perceptions of what constitutes an empathic approach can be confusing and misleading. The term empathy is used widely and continues to be popular and relevant across architecture and design. However, the term should be better understood and articulated in terms of the different assumptions, contexts and usages of its sources, to build a more robust basis for research and practice concerned with ‘empathy’. To deepen our understanding, we wanted to identify and articulate the differences within and across disciplines to clarify the philosophical approaches behind the various ways of empathising in design and architecture.

The framework of Mixed Perspectives in an empathic design process formed by design researchers Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout (Citation2016) helped us to further clarify empathy in design. They identified three perspectives defining the distance between designers and users. In their terminology designing conventionally, looking at the users from afar, without involvement, could be understood as a ‘third-person perspective’, activating the users in collaborative exercises and therefore designing for a known other could be understood as a ‘second-person perspective’, and when designers experienced the situation of the users personally, being part of the users’ ’system’, designing was in their words done from ‘a first-person perspective’.

2.1. Empathy in design: designing with a focus on the user

Empathy in design is thoroughly discussed in the seminal book Empathic Design, User Experience in Product Design (Koskinen Citation2003), in which the editors trace the concept of empathic design to the field of business studies, which is where it was introduced to gain an imaginative understanding of customers as part of the product design process and as a strategy for companies to achieve commercial success (Leonard and Rayport Citation1997). Empathic design has guided designers’ understanding of the needs and aspirations of end-users through observation and curiosity, even before the customers themselves could recognise those. Through involving the actual users in the design process, this approach has allowed industrial design to be personalised in a way that resembles customised products. Behind this approach is the view of the sociological theory of symbolic interactionism, focusing on the meaning people find in their interaction with things in their everyday life (Heidi Paavilainen, Ahde-Deal, and Koskinen Citation2017). The theory of symbolic interactionism is threefold; action depends on meaning and meaning derives on social interactions and can change over time (Blumer Citation1986). It stresses the importance of small interactions between individuals.

Today, the empathic design approach is widely adopted in the field of design, and it has entered into practice in various ways. For example, Ilpo Koskinen and Katja Battarbee (Citation2003) have described empathic design as a series of techniques that combine design and qualitative research. These types of techniques include design probing (Mattelmäki Citation2005, Citation2006), storytelling (Battarbee Citation2003), prototyping (Sanders and Stappers Citation2014), design games (Vaajakallio and Mattelmäki Citation2014), observation and shadowing (Fulton Suri Citation2003), and empathic handover (Smeenk, Sturm, and Eggen Citation2018; Smeenk et al. Citation2018), and they can be mixed and combined in various novel ways to enable empathic understanding of users’ experiences (Sanders, Brandt, and Binder Citation2010; Sanders and Stappers Citation2008, Citation2014).

According to the Mixed Perspectives framework (Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout Citation2016) the empathic design process could be seen as a second person perspective. They point out that empathic design discourse often focuses mainly on the user perspective, leaving the designer at a distance without accounting for the designer’s personal experience.

2.2. Empathy in architecture: designing from a distance

In his essay ‘Empathic and Embodied Imagination: Intuiting Experience and Life in Architecture’, architect and theorist Pallasmaa (Citation2015) discussed the issue of empathy in architecture from a phenomenological point of view by claiming that it is possible to empathise through imagination:

It is usually understood, that a sensitive designer imagines the acts, experiences and feelings of the user of the space, but I do not believe human empathic imagination works that way. The designer places him/herself in the role of the future dweller, and tests the validity of the ideas through this imaginative exchange of roles and personalities. Thus, the architect is bound to conceive the design essentially for him/herself as the momentary surrogate of the actual occupant. Without usually being aware of it, the designer turns into a silent actor on the imaginary stage of each project. At the end of the design process, the architect offers the building to the user as a gift. It is a gift in the sense that the designer has given birth to the other’s home as a surrogate mother gives birth to the child of someone who is not biologically capable of doing so herself. (Pallasmaa Citation2015, 12–13)

In Pallasmaa’s (Citation2015) view, the designers imagine themselves as the actual users and thus seek to experience similar emotions as users come to experience. This conscious experience of emotions according to a phenomenological approach happens from a first-person point of view (Woodruff Smith Citation2013). However, according to our understanding of the Mixed Perspectives framework (Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout Citation2016), this kind of imagined first-person point of view, lacking immersion with real users, would be defined as a third-person perspective.

2.3. Towards sensitivity and intimacy in design

Within design discourse, one step moving towards a deeper process is the emphasis on sensitivity. The techniques and methods of sensitive empathic design allow designers to empathise with people in different physical, social, and cultural contexts (Koskinen and Battarbee Citation2003; Mattelmäki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen Citation2014). Furthermore, developing sensitivity can help designers and other stakeholders to understand the diverse and transformative conditions of people. Mattelmäki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen (Citation2014) have identified four layers of sensitivity in the design process:

Sensitivity towards humans: gathering inspiration and information about and making sense of people and their experiences and contexts;

Sensitivity towards design: seeking potential design directions and solutions and posing ‘what if’ questions;

Sensitivity towards techniques: application of generative, prototyping, and visualising tools to communicate and explore the issues, and;

Sensitivity towards collaboration: tuning the process and tools according to co-designers, decision-makers, and organisations alike. (Mattelmäki, Vaajakallio, and Koskinen Citation2014, 76).

Point 4 is particularly meaningful beyond the traditional design realm, such as when design is acting as a moderator of change. In these kinds of situations, the need to build trust over time is crucial and supports the aim for achieving greater depth.

Based on their experiences with vulnerable communities in Cambodia, design researchers Hussain, Sanders, and Steinert (Citation2012) listed the difficulties they faced when using co-design tools due to local habits and culture. They advocated for awareness of the risks of superficial outcomes present in an empathic design approach, particularly if the users are in a vulnerable position or distances between stakeholders are substantial. Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum (Citation2019) have also underlined the importance of sensitivity to the other in intercultural situations for many reasons. For instance, the users might have been subject to previous consultations or research without outcomes, translations of concepts can be misinterpreted, or power relations might be unclear. Akama and Yee (Citation2016) have been critical of any traditions, including co-design, in which processes and methods are perceived as universal and replicable.

To understand the distances created by cultural differences, Akama and Yee (Citation2016) have utilised cultural philosopher Thomas Kasulis’s (Citation2002) theory that explains integrity as the relationship between seawater and sand: the waves of the sea form the sand and the beach forms the waves, but the sand remains sand, and the sea remains water. Regarding intimacy, Kasulis (Citation2002) has explained it as the relationship between water and salt that merge to become seawater. With this intimate orientation to design, the designer seeks to bring attention to cultural, emotional, and relational entanglements (Akama and Yee Citation2016). The call for social design to embrace difference and accommodate heterogeneity requests the inclusion of personal heritage in the empathic dialogue and allows for intuition and awareness of how the present moment unfolds (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019).

Through this approach, no design process is the same, and the methods are modified according to the distinctive heritage of the designers and users and the particular characteristics of their relationship. This is supported by clinical psychologist Rogers’s (Citation1961, 332) discoveries in his practice in the 1950s, in which

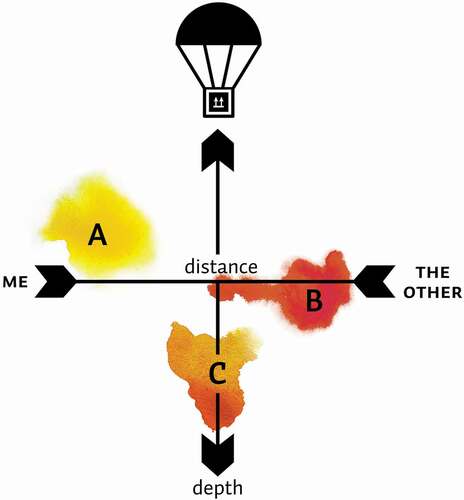

‘understanding with a person, not about him’ makes a significant difference in the relationship. In his case, the listener, and in our case, the designer, needs to be brave, as ‘you run the risk of being changed yourself’ (Rogers Citation1961, 333). As designers, we can willingly step into the voids that are not yet known and be open to potentiality (Akama Citation2015). This immersive yet open nature of the relationship between designers and users indicates a deep empathic engagement that allows the designer to feel from a first-person perspective according to the framework of Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout (Citation2016) ().

Figure 1. In empathic design, the focus is on the user, whereas in the empathic approach in architecture, the focus is on the architects’ experience. The distance between designer and user is shorter in empathic design than it seems to be according to the presentation of empathy in architecture literature. However, in the approaches aiming for depth in the relationship between designers and users, the roles are immersed and the emphasis on both parties is equal.

Based on the literature referred to above we could agree that the notion of empathy is fragmented in design. We collected the main characters of the different approaches studied in to articulate the notion. We utilised these three approaches when reflecting on a design project to identify when and in what form empathy was part of the design process.

Table 1. Result of literature review regarding different approaches to empathy in design

3. Elaborating on the empathic approach

In this paper we retrospectively study a maternal healthcare design project in which we were involved. This design project offers a typical example of a situation in which the distances between stakeholders are large and users are in a vulnerable situation. Therefore, the objectives of this paper, to enhance empathic engagement and depth in the design process align with the general demands of the maternal healthcare sector in low-resource settings.

3.1. Background to the design context

One task that lies before us is to ‘(re)humanise’ healthcare (Meguid Citation2016, 61). This target can be achieved through building a healthcare system that nurtures the agency of the patient, where the patient is perceived as an individual and supported with empathy. There are diverse ways to pursue this target, but one important factor among them is the architecture (Meguid Citation2016). Maternity wards focus on the birth of human beings and should ideally occur in places of care that emphasise dignity, quality care, and healing. In this regard, architecture can support women in embracing opportunities to influence, ask questions, and stand up for their rights, as well as shape healthcare workers’ experiences and attitudes (Meguid and Mgbako Citation2011). Healthcare facilities can be conduits for (or, if designed poorly, obstacles to) appropriate and therapeutic healthcare. Improvement of the quality of care in maternal healthcare facilities guarantees an end to preventable birth-related deaths and disabilities (Maaloe et al. Citation2016). Currently, women in low-income countries give birth in situations in which they are more often than not deprived of their dignity and are afforded neither privacy nor consideration of their need for emotional support. Additionally, healthcare providers often treat women in labour without sensitivity or empathy (Meguid and Mgbako Citation2011). Empathy in care can be created and nourished through empathic design processes (Akoglu and Dankl Citation2019).

The project used as an empirical example to illustrate the different empathic approaches was executed by a social impact company, M4ID (now known as Scope). The overall objective of the design project was to reduce maternal and infant deaths in low-resource settings through design solutions. M4ID formed three design teams, one on architecture (led by the main author of this paper), a second on services, and a third on products. Two prototype facilities were planned during the project phase – one in Kivunge, Zanzibar, Tanzania and another in Basta, Odisha, India. The design proposal for Zanzibar has not yet been constructed, while a refurbished facility in Basta was inaugurated on 15 December 2018. Our original intention with the design project was to design with empathy throughout the process, however specific empathic actions stayed vague and was difficult to specify amid the design process. This experience justified the need for a differentiated articulation on the notion of empathy that we are aiming for in this paper.

3.2. Positioning the authors

We oppose ‘fortifying a design culture of nowhere and nobody’ (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019, 4), and therefore we want to introduce the authors. Helena Sandman led the architecture team in the maternity ward design project. She is a practising architect who has been working in low-income countries for two decades. In the context of this design project, it is relevant to share that as a mother, she has delivered in an exemplary high-resource (in terms of personnel, time, equipment, and space) government maternity ward in Finland. The second author Tarek Meguid, is a practising medical doctor with origins in North Africa and Germany and professional experience of working as an obstetrician and gynaecologist in various African countries. He was instrumental in the design of the only two government maternity wards in Malawi, where every woman has her own private delivery room (Ethel Mutharika Maternity Wing, Kamuzu Central Hospital & Bwaila Hospital, both in Lilongwe, Malawi). The third author Jarkko Levänen, is an assistant professor of sustainability science with significant experience examining different aspects of social sustainability in developing countries.

3.3. Data collection and analysis

For this paper we reflected retrospectively on the maternity ward project. The reflective methodology we employed for this paper was discussed by Blythe and van Schaik (Citation2013) as naturally being part of an active design process. They identified three dynamic aspects of reflection: ‘reflect on’ previous projects, ‘reflect in’ the midst of the process on the next move, and ‘reflect for’ future projects (Blythe and van Schaik Citation2013, 62–63). Reflection is common in practice-led research, where the actions are guided by the practice or design process in the first place, research in the second. Also, practice-led design researchers Mäkelä and Nimkulrat (Citation2011) sees reflection in action and reflection on action as tools for analyses when developing design knowledge.

The background studies and participatory design activities for the maternity ward project were conducted primarily to inform and support the design project – not for academic purposes. During the design process, due to the complex and constantly changing situation, it was necessary for us to be creative and use an assortment of means and methods as well as to combine our own professional experience with local knowledge. We thus had a diverse collection of data to analyse consisting of our field notes from site visits, informal and formal interviews, workshop results, design probing responses, design sketches as well as photographs and video clips (Appendix I). Additionally, we had the results from a baseline study and an impact assessment conducted by an Indian research firm on our behalf. For this retrospective reflection we analysed the diverse data and the different methods used during the 3-year long design process and extracted some examples which substantiate the point of this paper. These examples illustrate, problematise, and discuss the three different empathic approaches defined in design literature (introduced in ) to elaborate on the challenges and potential of empathy and to motivate designers to deepen their empathic registers.

3.4. Examples of design situations connected to different approaches to empathy

In the following sections, we describe situations in the design process where empathy has played a role in the different ways presented in the theoretical part of the paper (). For the sake of clarity, we have chosen to use examples that led to a particular design solution.

3.4.1. Examples of an imaginative approach to empathy

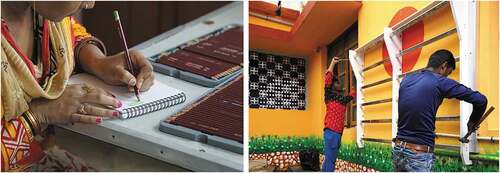

From our in-depth analysis, one example in particular highlights a situation that shows where using empathy from a distance can lead. Responses to questionnaires carried out in Odisha revealed that the majority of respondents were sedentary during labour; they were either lying down (62.7%) or sitting (6.9%). Women’s desire to move around during labour was not addressed by the participants in our co-design activities. However, in the current medical research, it is widely accepted that engaging in activity during labour is beneficial for the birthing process. This unexpressed desire might be the result of insufficient knowledge of the practice and no prior experience of moving during labour. Nevertheless, we introduced spaces that enabled mobility. The interior design of these spaces reflected directly user engagement, design probing responses and the personality of the locally hired artist. However, the solutions for mobility did not originate in direct responses from the users but from our background research, our observations, our own experiences of delivery, and from imagining being users of the space ().

Figure 2. Design probing had an impact on the interior design of the spaces, but did not suggest equipment for mobility, that ended up being untouched by the women in labour when the building was taken into use. Photos: Helena Sandman and Abhay Mohanty.

After the refurbishment of the facility in Odisha, the building had been in use for one month when an impact assessment was done. Regarding movement in the facility during labour, the findings were not positive:

Overall, the level of activity of women in labour did not change post the re-organisation of the space … As it is not common among these communities to exercise during labour, they are not aware of how to use the new equipment. In addition, the facility staff (nurses and birth attendants) did not educate them on the importance of active labour and the correct usage of equipment. (4th Wheel Social Impact Citation2019)

In this example, despite our good intentions, the resulting imaginative design solution might have been too far removed from the actual real-life situation on the ground, and it would therefore require further collaboration in order to properly enter into use.

3.4.2. Examples with a focus on the users’ needs

The issue of taking an empathic approach with a focus on the users’ needs also came to the fore in our research, with two notable examples. In Odisha, we engaged with mothers of new-borns who had not been given a bed in a room due to overcrowded facilities and therefore had to stay in the corridors. They were concerned for their babies, as they lay on the floor on blankets (). As a result of this engagement, we proposed offering a cardboard box that would protect the baby from draughts and prevent it from being stepped on. Once the baby was brought home, it could function as a first bed. The mothers were really happy with the prototype we presented. However, after having prototyped the solution, we realised that introducing this box would indicate an acceptance of the scarcity of space and would potentially prevent the Indian authorities from allocating funds for new maternal health facilities. Consequently, the box was never produced.

Figure 3. The spaces in the maternity wards in Odisha were often overcrowded. Due to a lack of space, corridors were also utilised as wards. One of the alternative solutions of the design process was a box to protect the infants. Photos: Helena Sandman.

In both Zanzibar and Odisha, women revealed in workshops and interviews that they were treated harshly by healthcare providers while in labour. The women in Zanzibar were not allowed to have a companion in the maternity ward during labour. Partly as a response to this alleged mistreatment, in our design for Zanzibar, we proposed private delivery rooms to allow for companions, a partner, relative, or supportive friend to attend the delivery. The companion would also be able to inform the nurse if there was a problem.

However, during one of our visits to a maternity ward in Odisha, where companions were allowed, we witnessed a mother-in-law force a delivering woman to hold her ankles with her hands for hours, slapping her as soon as she released her grip (). In this case, having a companion did not prevent mistreatment. Having gained this understanding, for the Zanzibar proposal, we redesigned the private rooms so that the nurses’ station would be in the centre to make the rooms more exposed.

Figure 4. We replaced the uncomfortable metal delivery tables with adjustable softer tables equipped with a leg support. Photos: Abhay Mohanty.

In Odisha, even if we could privately condemn the actions of the mother-in-law, as designers, we did not have the necessary influence to intervene in such a situation. However, through our design response, we could offer options. To address this particular situation, we changed the delivery beds to softer, adjustable beds that offered support for the feet (). This new bed, with its possibilities for adjustment, would perhaps indicate to the women, companions, and personnel that a delivering mother should be able to move according to her preference.

In these examples, the design solutions were responding to explicit demands for safety. The input was shared with us during a workshop in Zanzibar with a group of women and in Odisha during interviews. However, as in the example of the private delivery rooms and the baby box, our designs were not all watertight, as we noticed at a later stage.

3.4.3. Examples of the sensitive and intimate design orientation

One meeting in particular offers an example of intimacy and two design-related insights. When we visited a small maternity ward in Zanzibar that benefited from additional external funding, our impression was more positive compared to our impressions of the average government hospital. We perceived a calm and clean space that functioned smoothly and was not crowded. However, during interviews with traditional birth attendants and women in the neighbouring village, we learned that they perceived the experience of arriving at and moving around in the maternity ward to be awkward. The women shared with us their shame at being seen in pain. In this maternity ward, the women in labour stayed in one room until the last moment when they were ready to push. Then, they were supposed to move to the delivery room by walking down the corridor where parents and children queued for antenatal care. This meant that delivering women felt as though they were being paraded in front of the whole village when they were at their most vulnerable. This knowledge and reflection deepened our understanding of the complex matrix of actors and phases in the delivery process and forced us to figure out how the organisation of space could reflect and support the integrity of the delivering woman in the best way ().

Figure 5. Renderings of the design for Zanzibar. In the design solutions for Zanzibar the spatial order was designed, to protect the integrity of the women. Renderings: Petter Eklund.

During our session with the same group of women, we shared our experiences of birthing positions and compared them with how they delivered. They taught us how to utilise the stools women use for home births in their village. This low, simple stool with handles supports a woman as she holds a steady position by leaning against the wall and planting her heels into what is often an uneven dirt floor (). According to the women, this position was ideal for delivery. This stool has similarities to the medically proven birthing stools currently on the market; however, assuming the position of leaning against a wall with your feet firmly planted and having the opportunity to draw the stool towards the body created a particularly strong stance. Unfortunately, these stools were not available in any of the facilities we visited in Zanzibar, a stainless-steel bed was the only option for delivery (). Consequently, we incorporated the stool and a nonslip floor into our design for the delivery rooms.

Figure 6. A common stool in Zanzibar used for delivery and many other purposes. The need to move around during labour is not always recognised, and the delivery beds in the maternity wards were flat and made of stainless steel. Photos: Helena Sandman.

In this encounter, all three parties – designers, traditional birth attendants, and women – were able to share their birthing experiences and together reflect on the advantages and disadvantages in this process. Laughing while trying out the stool brought intimacy into the encounter. It was a mutual learning experience on an intimate level. We could compassionately empathise with how the women had experienced their births. Our understanding of the situation of women in this area would have been very different if we had relied only on our experiences of visiting the facility, our interpretations of the workshop responses, or our imaginative capacities.

4. Discussion

In the following, we will reflect on how different approaches to empathy affect the distance between the designer and the user and if, by understanding the particularities of the different approaches, this distance can be reduced and depth created in the design process.

What we have been describing as empathy from a distance, where the designer merely relies on imagination, has been criticised because it might not always accurately reflect the actual situation of the user (Morton Citation2017). Moreover, one’s imagination might only partially correspond to reality. For instance, when designing maternity wards in general, not all architects have experienced pregnancy and labour themselves, and therefore they might not accurately understand (or be capable of imagining) the situation. However, as in the example presented in section 3.4.1 (regarding mobility during labour), despite having had our own experiences of labour, our design result did not turn out perfectly. However, circumstances do not always allow for physical engagement with users; therefore, optional ways of including empathy in the design process are valuable. Furthermore, architects and designers remain an integral part of the design process and will, on top of engaging methods, still imagine themselves as users according to Pallasmaa’s (Citation2015) theory. This means that they cannot and should not erase their own experience since it is also valuable. Honestly recognising one’s limits and possibilities as a designer positions the design (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019).

In the empathic design approach, the users inform designers. However, this approach can sometimes be superficial due to a rigid focus on methods that lack culturally embodied critical engagement because the format of the methods might not be customised according to the users (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019). In the design project we discussed in the previous section, a great deal of information and understanding was shared through encounters in the form of dialogue. Nonetheless, we noticed that if this dialogue was not conducted with sensitivity – if, for instance, it happened in a hurry, in an uncomfortable space, or if there were uncertainties – emotions might be misinterpreted and the sense of openness disappear. Additionally, focusing on the user’s point of view alone might exclude other components, as in our example of the baby box in section 3.4.2, when only in a later stage was the complete situation revealed to us. There are also risks we need to be aware of when taking an empathic approach. Anthropologist and psychoanalyst Douglas Hollan (Citation2017) warned that knowledge obtained through an empathic approach can be misused, even if the original intentions were good. For instance, as designers, we need to be aware that personal information shared in confidence might be revealed through design solutions.

To take empathy to a more intimate and sensitive level, we need to open up and let the other ‘inside’ by searching for existing similarities and taking an interest in our differences. Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum (Citation2019) described the Maori method of collaboration as taking the form of three questions: ‘Who am I?’, ‘Who are you?’, and ‘Who are we?’ Before we can collaborate, we need to know ourselves and others. These questions build a base for an empathic approach and resonates with the Mixed Perspectives framework of Smeenk, Tomico, and van Turnhout (Citation2016). In taking an intimate and sensitive approach, the distance between me and the other is reduced when compared to both the approach of empathic design with focus on the users and of empathy with an emphasis on imagination from a distance because ‘my experience’ is closely linked to ‘the experience of the other’. This is not always easy to achieve and requires making an effort. The process might be uncomfortable, and there may be moments of unease when differences appear. Diving deep into empathy can eventually cause a strong counterreaction of empathic or personal distress if the balance between the identification and distinction between me and the other is not preserved; distress often prevents action (Maibom Citation2017).

For designers to develop depth in their design, they need to be sensitive to both users and themselves to be able to establish a connection of trust with the users and to follow their intuition. Ideally, this relationship permits the creation of intimacy between designers and users, according to Kasulis’s (Citation2002) and Akama and Yee (Citation2016) definitions, where similarities as well as differences between emotions, cultures, and habits are sensed andexchanged.

5. Conclusions

Our practice motivated a need for a more nuanced understanding of empathy. Our account of the origins, contexts and usages of empathy follows Akama and Yee (Citation2016) critique of a universal and replicable assumption in co-design, yet provides an enriched and deepened terminology and conceptualisation for empathic approaches. This paper builds an analysis of various significant approaches to the notion across architecture and design while recognising the value of unboxing and embracing contrasting theories. By retrospectively revisiting the design project, we could identify several possibilities for empathy to have a significance throughout the design process. Thus, we propose a variation of registers of empathy with different particularities. Our analysis led us to here establish three registers of empathy: distance, connection, and depth ().

Figure 7. Placement of the different registers of empathy in relation to a ‘parachute’ design approach without user involvement and an in-depth design process. A, stands for Empathy from a distance, B, for Empathy through connection, and C, for Empathy in depth.

A. ‘Empathy from a distance’ embodies the value of the architect’s/designer’s presence and capacity to employ personal experiences and an active motivation to imagining being the user. In this register, the architect/designer is strongly embodied, and the actual user is often obscured. This register can give designers and architects the freedom to introduce new innovative solutions that promote development. However, it also has limitations and can result in an outcome that is not adopted by the users.

B. ‘Empathy through connection’ emphasises the users with a pragmatic focus on their activities, emotions, and aspirations through practical methods and tools. In this register, the users are in the spotlight. The designers and architects are seeking to understand them with sensitivity, curiosity, and integrity. This register gives users a voice and a part to play in the design process.

C. ‘Empathy in depth’ proposes that the designers and architects take a step closer to the users, seek out similarities and differences, and aim to reduce distances between stakeholders with compassion. This happens through establishing an intimate connection with the environment, culture, and users. This register connects the two previous registers as the designers/architects, users, and other stakeholders share experiences and form a collective understanding.

Through presenting these registers, we seek to draw attention to the potential offered by empathic engagement and help designers to be aware of different kinds of empathic behaviour. The empathic approach can extend from the very beginning of a design process throughout the project and beyond. We can be empathic from a distance and when closely immersed with the users. There is no need to exclude one or another register of empathy, they can all be combined to complement each other or utilised in different circumstances, where one form might be more appropriate than another. We also acknowledge the possibility for other registers to appear in different contexts. The use of registers of empathy can have a wider value not only for research within and across fields, but also for practice. For architects and designers, mastering empathy implies a competence to practice in an intuitive, contextual and agile way.

When reflecting on the case illustrated in this paper, we found that through a design process that applies several registers of empathy there is the potential to create a space in which women, their infants, and their families can ‘show up’, find their voices (literally and metaphorically), and be heard. We invite further explorations of whether empathy between the actors in the design process can lead to spatial solutions that support empathic encounters. When we as designers strive for depth in the design process it allows for true meetings that are so intimate that neither party fears their differences and where both parties are open to possible development. When design is born through meetings of this kind, the created architecture potentially becomes an environment supporting meetings alike.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (191.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The research reported in this paper was conducted at Aalto University in the Department of Design in the School of Arts, Design, and Architecture as part of the New Global research programme. The authors want to acknowledge the social impact company Scope (formerly M4ID) for their collaboration during the Lab.Our Ward design project. Additionally, we would like to thank Pamela Allard from Health Improvement Project Zanzibar (HIPZ) and Angela Giacomazzi at the Kendwa Maternity Clinic for supporting the background research in Zanzibar. We would also like to thank traditional birth attendants, Riziki Machano Khamisi and Kidawa Makame Haji, from Kendwa village in Zanzibar for sharing their experiences with us. The Lab.Our Ward project at M4ID was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. We also gratefully acknowledge receiving funding from the Finnish Funding Agency of Technology and Innovation (Business Finland) and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. Last but not least we want to thank Professor Ramia Maze and the Co-design reviewers for their support in developing this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- 4th Wheel Social Impact. 2019. Evaluation Report Lab.Our Ward Project, Odisha. Mumbai: 4th Wheel Social Impact.

- Akama, Y. 2015. “Being Awake to Ma: Designing in Between-Ness as a Way of Becoming With.” CoDesign 11 (3–4): 262–274.

- Akama, Y., P. Hagen, and D. Whaanga-Schollum. 2019. “Problematizing Replicable Design to Practice Respectful, Reciprocal, and Relational Co-Designing with Indigenous People.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 59–84.

- Akama, Y., and J. Yee. 2016. “Seeking Stronger Plurality: Intimacy and Integrity in Designing for Social Innovation.” In Proceedings of Cumulus Hong Kong 2016, edited by C. Kung, A. Lam, and Y. Lee, 173–180. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Design Institute.

- Akoglu, C., and K. Dankl. 2019. “Co-Creation for Empathy and Mutual Learning: A Framework for Design in Health and Social Care.” CoDesign. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2019.1633358.

- Battarbee, K. 2003. “Stories as Shortcuts to Meaning.” In Empathic Design: User Experience in Product Design, edited by I. Koskinen, K. Battarbee, and T. Mattelmäki, 107–118. Helsinki: IT Press.

- Blumer, H. 1986. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

- Blythe, R., and L. van Schaik. 2013. “What If Design Matters?” In Design Research in Architecture, edited by M. Fraser, 53–69. Dorchester: Dorset Press.

- Fulton Suri, J. 2003. “Empathic Design: Informed and Inspired by Other People’s Experience.” In Empathic Design: User Experience in Product Design, edited by I. Koskinen, K. Battarbee, and T. Mattelmäki, 51–59. Helsinki: IT Press.

- Gregory, J. 2003. “Scandinavian Approaches to Participatory Design.” International Journal of Engineering Education 19 (1): 62–74.

- Heidi Paavilainen, H., P. Ahde-Deal, and I. Koskinen. 2017. “Dwelling with Design.” The Design Journal 20 (1): 13–27.

- Hollan, D. 2017. “Empathy across Cultures.” In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy, edited by H. Maibom, 341–352. Oxford: Routledge.

- Hussain, S., and E. B.-N. Sanders. 2012. “Fusion of Horizons: Codesigning with Cambodian Children Who Have Prosthetic Legs, Using Generative Design Tools.” CoDesign 8 (1): 43–79.

- Hussain, S., E. B.-N. Sanders, and M. Steinert. 2012. “Participatory Design with Marginalized People in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities Experienced in a Field Study in Cambodia.” International Journal of Design 6 (2): 91–109.

- Kasulis, T. 2002. Intimacy or Integrity: Philosophical and Cultural Difference. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Keshavarz, M., and R. Maze. 2013. “Design and Dissensus: Framing and Staging Participation in Design Research.” Design Philosophy Papers 11 (1): 7–29.

- Koskinen, I. 2003. Empathic Design: User Experience in Product Design, edited by I. Koskinen, K. Battarbee, and T. Mattelmäki., 7–10. Helsinki: IT Press.

- Koskinen, I., and K. Battarbee. 2003. “Introduction to User Experience and Empathic Design.” In Empathic Design: User Experience in Product Design, edited by I. Koskinen, K. Battarbee, and T. Mattelmäki, 37–50. Helsinki: IT Press.

- Leonard, D., and J. F. Rayport. 1997. “Spark Innovation to Empathic Design.” Harvard Business Review 1997 (November–December): 102–113.

- Maaloe, N., N. Housseine, I. C. Bygbjerg, T. Meguid, R. S. Khamis, A. G. Mohamed, B. Bruun Nielsen, and J. van Roosmalen. 2016. “Stillbirths and Quality of Care during Labour at the Low Resource Referral Hospital of Zanzibar: A Case-Control Study.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16 (351): 1–12.

- Maibom, H. 2017. “Introduction to Philosophy of Empathy.” In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy, edited by H. Maibom, 1–10. Oxford: Routledge.

- Mäkelä, M., and N. Nimkulrat 2011. “Reflection and Documentation in Practice-led Design Research” Proceedings of Nordic Design Research Conference. Helsinki.

- Mattelmäki, T. 2005. “Applying Probes – From Inspirational Notes to Collaborative Insights.” CoDesign 1 (2): 83–102.

- Mattelmäki, T. 2006. Design Probes. Helsinki: University of Art and Design.

- Mattelmäki, T., K. Vaajakallio, and I. Koskinen. 2014. “What Happened to Empathic Design?” Massachusetts Institute of Technology Design Issues 30: 67–77.

- Meguid, T. 2016. “(Re)humanising Health Care – Placing Dignity and Agency of the Patient at the Centre.” Nordic Journal of Human Rights 34 (1): 60–64.

- Meguid, T., and C. Mgbako 2011. “The Architecture of Maternal Death.” [Accessed 12 May 2019]. https://rewire.news/article/2011/04/04/architecture-maternal-death/

- Morton, A. 2017. “Empathy and Imagination.” In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy, edited by H. Maibom, 180–189. Oxford: Routledge.

- Pallasmaa, J. 2015. “Empathic and Embodied Imagination: Intuiting Experience and Life in Architecture.” In Architecture and Empathy, edited by P. Tidwell, 4–18. Helsinki: Tapio Wirkkala Rut Bryk Foundation.

- Rogers, C. R. 1961. On Becoming A Person: A Therapist’s View on Psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., E. Brandt, and T. Binder. 2010. “A Framework for Organizing the Tools and Techniques of Participatory Design.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, edited by T. Robertson, K. Bodker, T. Bratteteig, and D. Loi, 95–198. Sydney: Association for Computing Machinery (ACM).

- Sanders, E. B.-N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18.

- Sanders, E. B.-N., and P. J. Stappers. 2014. “From Designing to Co-Designing to Collective Dreaming: Three Slices in Time.” Interactions 21 (6): 24–33.

- Smeenk, W., J. Sturm, and B. Eggen. 2018. “Empathic Handover: How Would You Feel? Handing over Dementia Experiences and Feelings in Empathic Co-Design.” CoDesign 14 (4): 259–274.

- Smeenk, W., J. Sturm, J. Terken, and B. Eggen. 2018. “A Systematic Validation of the Empathic Handover Approach Guided by Five Factors that Foster Empathy in Design.” CoDesign 1 (21): 1–21.

- Smeenk, W., O. Tomico, and K. van Turnhout. 2016. “A Systematic Analysis of Mixed Perspectives in Empathic Design: Not One Perspective Encompasses All.” International Journal of Design 10 (2): 31–48.

- Vaajakallio, K., and T. Mattelmäki. 2014. “Design Games in Codesign: As a Tool, a Mindset and a Structure.” CoDesign 10 (1): 63–77.

- Woodruff Smith, D. 2013. “Phenomenology”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. [Accessed on 24 June 2020]. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/

Appendix I.

Summary of methods used in the design process, 2015–2018