ABSTRACT

Despite much criticism, global digital platforms hold some promise for small-scale entrepreneurs (SSEs) in the global south. However, they are often excluded from direct participation in global initiatives, such as crowdfunding. Besides socio-cultural disparities, accessibility and adoption issues, technology usage and integration present a major challenge. To bridge those gaps we propose a workable model consisting of a local tech mediator operating on a digital platform connecting local SSE to global digital services. We have engaged a group of informal settlement SSE in Windhoek, Namibia to jointly conceptualise the roles, tasks and responsibilities of a local tech mediator, concurrently with technical skills training as well as the development of an international crowdfunding campaign. We assert that the jointly developed concepts of a local instantiation of the model as well as the co-design process have enabled us to create model, which would allow the utilisation of global digital platforms for SSEs in the global south.

1. Introduction

Globalisation and digitalisation are rapidly changing economies worldwide. While they offer much opportunity for growth, they also reinforce existing inequalities fostered through the digital divide (World Bank Citation2016). Digital platforms have been criticised for furthering the economic inequalities by exploiting their users to benefit the platform owners (Srnicek Citation2017; Poderi Citation2019; Wood et al. Citation2019).

Much of the debates have been from a global north standpoint (Koskinen, Bonina, and Eaton Citation2019; Ahmed et al. Citation2016) with little consideration what those global platforms could mean in resource stricken environments from a local perspective.

Crowdfunding networks: Structure, dynamics and critical capabilities Participation on these platforms enables communities to access global marketplaces, and turn resources into financial assets (Keskinen et al. Citation2020), or to get more efficient service delivery (Hira Citation2017). Platform-directed crowdfunding specifically has the potential to create jobs and spur innovation in the global south (Best et al. Citation2013), and empower the economic development of women in particular (Pekmezovic and Walker Citation2016). In light of these opportunities, we investigate how communities from the global south could access and benefit from global platforms, and specifically crowdfunding.

Local entrepreneurs in the global south are facing their own particular challenges in terms of usage of digital platforms. For example, 24/7 affordable Internet access, online payment facilities, and mastery of English or other dominant languages are unquestioned givens in digital market spaces, thereby excluding those who do not operate within those conditions. Moreover, efforts of local innovations are often not supported by global platforms (Nicholson et al. Citation2019), hampering a seamless integration with locally co-designed digital services (Arvila et al. Citation2020). Thus, a more holistic approach from a southern perspective is required to ensure inclusiveness of global platforms.

In this paper, we are proposing a workable solution which has been co-designed with Namibian informal settlement entrepreneurs. We present the concept of ‘tech mediator’ collective, consisting of local community members, skilled in the usage of international digital services, and bridging the use for their fellow community members. The tech mediators’ role is to facilitate the usage of global (north) digital services by local members from the global south. The aim of this paper is to present a practical solution on how global platforms can effectively be accessible for users in the global south as well as share the process of co-designing the tech mediator collective.

2. Co-design in the era of platforms

Recently, the role of co-design in developing platforms has been discussed, in confronting the hegemony of platform capitalism, where the collaboration of many is turned into profits by the platform owners (Srnicek Citation2017; Avram et al. Citation2019). Digital platforms have permeated society, rendering services efficiently; however, their neo-liberal values have been questioned (Brown, Choi, and Shakespeare-Finch Citation2019). Instead of platform capitalism, the co-design community has supported alternatives, such as platform collectivism, being mutual beneficial for stakeholders (Carroll and Beck Citation2019). Co-design projects have facilitated a more equal participation, such as a citizen-centric city-planning (Light and Seravalli Citation2019); and commonfare.net, where underprivileged populations have been able to share their stories, and find dignity and meaning (Bassetti et al. Citation2019). Non-extrativist alternative platforms, also understood as commons, have collectively managed resources that are used to benefit the users (Poderi Citation2019).

Srnicek (Citation2017) has categorised the different types of platforms with their own unique characteristics and issues, namely into; advertising, cloud, industrial, product, and lean. Crowdfunding fulfils the criteria of a lean platform– the platform owners have reduced their ownership to the platform itself, and profit by taking a share of transactions performed in the platform. Crowdfunding platform users, who are seeking funders, do unpaid work in creating campaigns, and the platform owners benefit from this work. While the usage of crowdfunding platforms can be beneficial for the fund seekers, the labour by them (and potential funders) maintains the profits of the platform owners. However, crowdfunding platforms may offer the unbanked users a service that has been previously monopolised by banks. The platforms might sometimes even explicitly aim at creating socially sustainable alternatives for previous models of funding projects (Light and Briggs Citation2017), while profiting from project shares (Meyskens and Bird Citation2015).

Common to co-designed platforms has been that users are peers and have similar needs of use. However, literature on multi-sided market platforms has been scarce. Multi-sided platforms create value for their owners and users by facilitating communication between different types of users (Hagiu and Wright Citation2015). In principal participatory approaches such as co-design posses tool boxes to facilitate exactly such inter-group design initiatives addressing power relations (Keskinen and Winschiers-Theophilus Citation2020). In this paper, we aim at finding a way of facilitating constructive participation on global multi-sided platforms via participatory design, and pose the research question ‘How co-design can contribute to a workable solution on the usage of multi-sided digital platforms by global south users?’

3. Rationale for design intervention

In 2014 Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST) established a long-term collaboration with marginalised youth in Havana, an informal settlement in Windhoek, Namibia, to co-design digital services aimed at improving the well-being of community members (Winschiers-Theophilus et al. Citation2017). National and institutional ethical approval was granted for the project as well as sub-activities, such as the one presented in this paper.

We were particularly interested in building on one of the projects, which was concerned with supporting entrepreneurs in Havana through crowdfunding (Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses (Citation2018) and Winschiers-Theophilus et al. (Citation2015)). Thus, the aim of this research is to implement a workable yet generalisable solution for local entrepreneurs to connect to global digital services, such as crowdfunding.

3.1. Background of Namstarter

During the exploratory stage of attempts to combat youth unemployment in Windhoek, and Havana in particular, crowdfunding was considered a promising solution to support young entrepreneurs lacking seed funds (Ongwere Citation2015). In 2016, the first version of a local crowdfunding platform called ‘Namstarter’ was co-designed with Havana youth and NUST students, and a prototype was developed by a honours student. The youth design participants were the first to upload their own projects onto the platform. Usability issues with the system were simultaneously resolved, and skill gaps in business planning, budgeting, marketing and media production were addressed through training sessions provided by RLabs Namibia (Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses Citation2018).

To ensure adoption of the platform among the wider Havana community, a local technology adoption strategy was co-designed with the youth participants (Goagoses, Kambunga, and Winschiers-Theophilus Citation2018; Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses Citation2018). Their role was to explain the concept of crowdfunding to fellow young people, as well as to introduce the technology and co-facilitate training sessions and workshops in areas such as project management and marketing to capacitate community members (Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses Citation2018). A final version of Namstarter was launched and deployed in 2017 under the management of RLabs Namibia, containing 41 Havana projects.

3.2. Need for re-conceptualisation

Major challenges have hampered the successful operation of the platform. One of the most important goals of crowdfunding platforms is to create a paying public, that is willing to donate or invest money to projects presented in the platform (Light and Briggs Citation2017), and Namstarter has failed to do that.

One of the reasons for the failure is related to technical issues such as the resolution of online payments as well as the administration of the website. Considering that Namstarter in its current state does not attract enough funders willing to carry out local bank transfers, the amounts received have been minimal.

A second is the promotion and visibility of the platform among possible funders within and outside Namibia. With this still unresolved, the Havana entrepreneurs have not yet received funds. Often, money raised by crowdfunding campaigns is sourced from close social circles around the campaign founder (Agrawal, Catalini, and Goldfarb Citation2014). However, in the case of small-scale entrepreneurs (SSEs) operating in an informal settlement, close circles do not have the resources to invest in fellow community members. Thus, funding needs to be sourced from outsiders, meaning projects need to be visible and attractive to strangers.

Due to these reasons, entrepreneurs are still anxiously awaiting funds. Thus, a re-conceptualisation of the system is required to ensure a workable solution within this specific context. In 2019, technical support was taken over by the inclusive and collaborative Tech Innovation Hub to capacitate Havana youth to maintain and administer their own system while hosting the digital service.

3.3. Bridging gaps

To reach funders internationally, we started to explore the possibilities of accessing global crowdfunding platforms. Our goal is to enable the interaction between SSEs in the global south, and potential funders in the global north. We identified four distinct gaps between them as represented in .

3.3.1. Gap 1: socio-cultural gap

There is socio-cultural disparity (Gap 1) between international funders and SSEs, who often live under different circumstances, have different cultural backgrounds and languages, which hampers their effective communication (Arvila et al. Citation2020). Creating value in multi-sided markets, including crowdfunding platforms, requires interaction between different types of users (Fehrer and Nenonen Citation2019; Hagiu Citation2014). These cultural differences might result in misunderstandings in communication (Kim Citation2005; Ting-Toomey Citation2005). Although cultures in the global south and global north are not monoliths, it is expected that the cultural differences are larger in south-north collaborations than they would be in more local ones. Additionally, in crowdfunding, the challenge of communication lays with the SSEs, in an attempt to attract funders.

3.3.2. Gap 2: accessibility & adoption gap

The introduction of global digital service platforms has created an accessibility and adoption gap (Gap 2) by global south users needing additional technical skills, infrastructure, and communication competences. Financial, technical, cultural, and social barriers have been identified as factors hindering the adoption of international services for users in the global south (Pankomera and van Greunen Citation2019). These users might not have access to banking services (Deen-Swarray, Ndiwalana, and Stork Citation2013), or lack the access to digital devices, broadband, and electricity (Wresch and Fraser Citation2011). Additionally, the users in the global south might lack the knowledge about existing services (Boateng et al. Citation2014; Osei-Assibey Citation2015) or do not trust them (Gbadegeshin et al. Citation2019; Lafraxo et al. Citation2018). The global platforms are mostly designed to match the needs of the users in the global north. This makes the availability of the global services even lower for the SSEs.

3.3.3. Gap 3: usage gap

Attempting to resolve this second gap through the implementation of local digital platforms has revealed a usage gap (Gap 3) with the lack of global north users engaging on those platforms due to trust, awareness, and other issues (Kang et al. Citation2016; Lacan and Desmet Citation2017). Trust in the crowdfunding platform is needed for users to donate or invest their money (Gerber and Hui Citation2013; Kang et al. Citation2016; Kim et al. Citation2017; Möhlmann and Geissinger Citation2018). Additionally, usability and good website design are essential (Kuo and Wu Citation2014; Masele and Matama Citation2019). The ease of monetary transactions is especially critical (Lacan and Desmet Citation2017). The same cultural and accessibility factors that make gaps 1 & 2 more intense for SSEs in the global south, affect the use of local platforms by global north users. These localised platforms are designed for culturally different groups, and the users in global north might simply lack the knowledge of them.

3.3.4. Gap 4: integration gap

We speculate that there are ways to technically connect the local digital platforms to the global ones. However, this has not yet been realised, given the differences in the translation of standards, languages, expectations and so forth. Furthermore, the global digital platforms have often been developed with the users in developed countries in mind. The users in the global south might lack credit cards, bank accounts, permanent home addresses, etc., which are requirements for using these platforms. Thus, it is not enough to just design new user interfaces, but to find workarounds for these underlying issues in order to make the global platforms connectable to the local ones.

3.4. Concept of tech mediator

In order for SSEs and funders to communicate, they need to operate on the same platform. However, there has been difficulties for SSE’s accessing global platforms (Gap 2), funders accessing local platforms (Gap 3), or trying to connect the local platform to the global one (Gap 4). Additionally, even if the parties were on the same platform, the differences of their contexts would still hinder their communication (Gap 1).

Considering that a number of the informal settlement entrepreneurs do not have bank accounts or reliable access to the Internet to maintain their own campaigns, the idea of maintaining individual campaigns on a global platform seemed unattainable. Building a technical solution to connect Namstarter to global platforms did not appear feasible due to associated technical challenges. The scale of our project also did not allow us to attract global north users for the local platform. Thus, another approach for bridging the gaps was needed.

Thus, we devised the concept of a ‘tech mediator’. A tech mediator is a person among underprivileged communities, who is knowledgeable in the usage of global digital platforms and who can mediate for their peers. Tech mediators can distribute information about beneficial digital services among their peers, assist them in using these services, and bridge the cultural gap between users. In short, tech mediators could act as a human interface for their peers to use global digital services.

Using a participatory approach, we have co-defined and implemented a tech mediator collective among Havana entrepreneurs, while designing a global crowdfunding campaign for Namstarter. Ultimately, we derived a tech mediator collective model, which describes the capabilities, roles, and responsibilities required to ensure local communities from the global south can equally benefit from global (north) platforms and digital services. Thus, we contribute a practical approach to bridge the gap between local communities and global digital services, which could be replicable in similar contexts.

Instead of individual projects, it was decided that we would upload Namstarter as one project managed by tech mediators. The money gathered through the campaign would then be distributed to the individual entrepreneurs by a committee of community members. In this scenario, Namstarter would have acted as a sort of business incubator for the local SSEs. Namstarter itself would be funded through the crowdfunding campaign, and it would have offered both funding and other support for the local SSE. The tech mediators were trained to both run the crowdfunding campaign, and to help the local SSEs in reaching their own entrepreneurial goals by providing them support in utilising digital services.

In this paper, the focus is given to the role of the tech mediators towards the community. Our aim is to examine what skills and knowledge tech mediators need help local SSEs.

4. Co-designing the tech mediator

In April 2019 we ran a one-week training and design workshop with selected Havana community members at the local collaborating university. The workshop had two goals: 1) to develop and define the role of the tech mediator further within the given context of the participants and 2) to produce a global Namstarter crowdfunding campaign. The focus of this paper is on goal 1.

4.1. Participants and facilitators

The workshop was held with a total of 10 participants from the communities. Six of them were from Havana and four came from indigenous rural communities who were about to develop a similar crowdfunding platform. In this article, we only focus on the Havana participants, affiliated with Namstarter, consisting of three females and three males. Of the participants, only two were able to attend all six sessions. The other four attended irregularly due to health reasons, sudden family emergencies, or transportation challenges. The participants were aged between 21 and 52 and all spoke English. They were invited on the basis that they were part of the previous co-design of Namstarter and its adoption strategy (Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses Citation2018). As they had previously attended the local crowdfunding efforts, they were all familiar with the idea of crowdfunding and with Namstarter in particular. All of them also had their own crowdfunding campaign on Namstarter.

The facilitators consisted of two Finnish researchers and three Namibian-based researchers from the local university as well as a professional local media consultant. The local team consisted of the Namstarter developer, the tech hub innovation coordinator and a supervising professor. The Finnish postgraduate students, had both spent more than 6 months in the country, were well acquainted with the community and affiliated with the project through a bilateral university collaboration. The Finish students facilitated most sessions in consultation with the local counterparts.

During the workshop, both written and audio recordings were made. The audio notes were transcribed post-situ. The participants created posters about the future roles of tech mediators, and these posters were scanned. A role-playing exercise was also recorded and transcribed. The data was then labelled according to our initial tech mediator concept by the two Finnish researchers. The selection of data presented in this paper was made on the basis of its relevance for the tech mediator concept in discussion with all researchers involved.

4.2. Intervention approach

We followed an action research approach deploying participatory design methods, considering that this research builds on previous research and development collaborations with Havana community members who are familiar with these methods. Similar methods have been previously used by Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses (Citation2018) and Winschiers-Theophilus et al. (Citation2015). Thus, upon identification of the problem of Namstarter not providing entrepreneurs with the expected funds, we designed an action, namely a joint conceptualisation of a tech mediator concurrent with a skill training and the development of a global Namstarter campaign.

4.3. Technical content

We had previously identified the features of successful crowdfunding campaigns and the technical skills needed to create these. Running a crowdfunding campaign requires significant effort from the campaign founders (Belleflamme, Lambert, and Schwienbacher Citation2013; Cordova, Dolci, and Gianfrate Citation2015; Mollick Citation2014). Creation of persuasive media is important skill in creation of crowdfunding campaign (Mitra and Gilbert Citation2014; Mollick Citation2014). In addition to the human and financial resources needed, knowledge about crowdfunding and crowdfunding campaigns is also required (World Bank Citation2015)

Based on the literature, we developed a lesson plan consisting of topics that would help the participants to develop and manage a successful crowdfunding campaign for a global platform. Our aim was to teach the required skills to the tech mediators, co-design the tech mediator collective and simultaneously create the crowdfunding campaign for Namstarter.

The lesson plan consisted of following topics, and it is further elaborated by Arvila et al. (Citation2020):

Basics of Crowdfunding

Persuasive Media Content and Camera Skills

Script-Writing

Filming in Practice

Editing

Campaign Creation and Management on Platform

4.4. Tech mediator design sessions

Dedicated sessions were allocated to the co-design of the tech mediator collective. In the first session the participants jointly created a tech mediator persona, then the concept was tested and refined through a role-play exercise and finalised in a participant-led discussion.

4.4.1. Tech mediator’s role

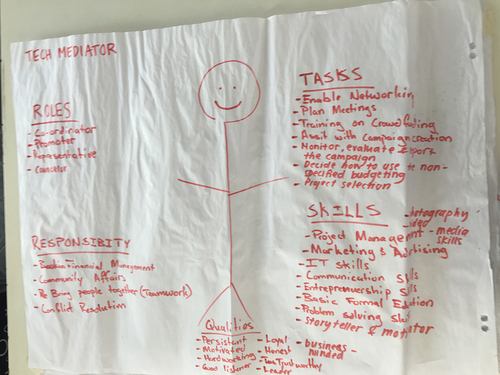

In the first tech mediator session, participants created a persona-like description of the roles of the tech mediator in the Namstarter project. The three main roles for the tech mediator that emerged during the persona creation sessions were as follows: 1) entrepreneurial advisor, 2) crowdfunding advisor, and 3) community informant. The poster created in the workshop is presented in .

According to the participants, the role of the entrepreneurial advisor would be to teach entrepreneurial skills to community members; provide examples of good business ideas; help with the financial side of running a business, such as teaching other community members record-keeping skills or general financial skills for business; and discussing the location of future businesses with community members and helping them to write business proposals.

The task of the crowdfunding advisor would include sharing knowledge about crowdfunding possibilities; creating crowdfunding campaigns; finding people who would like to create their own crowdfunding campaigns; teaching about photo- and video-shooting and editing, storytelling, and marketing, and teaching computer skills if needed.

The community informant is responsible to coordinate and inform the community about events; invite youth to workshops; ask community leaders to visit the crowdfunding projects; and inform the government about new businesses.

4.4.2. Role-playing activity

The purpose of this session was to help participants think of ways to communicate with potential funders and clarify the tasks and processes of the crowdfunding advisor.

One of the participants was selected to act in the role of crowdfunding advisor. The crowdfunding advisor discussed the crowdfunding campaigns of other participants with them and then presented the campaigns to the funders. Meanwhile, the crowdfunding advocate was advised to ask additional questions and challenge community members if they were not able to describe their projects with sufficient detail. Next, the crowdfunding advocate presented the projects to the researchers, who played the role of potential funders, in order to convince them to fund the projects. The researchers were also advised to ask specifying questions from the crowdfunding advocate.

The crowdfunding advocate required guidance on his performance when presenting the community project ideas to the researchers. In the beginning, he was able to gather the required knowledge from the community members. He asked questions about the applicability of the projects, how much money they would need, and how that money would be used. However, when community members asked him to explain what crowdfunding was, he was not able to provide a correct definition.

Furthermore, when presenting the projects to the researchers, the participant introduced himself by saying, ‘I am the Namstarter connection for the community. ‘ However, he did not explain anything else about Namstarter or the reason why he was in his role. After that, he introduced the project to the researchers and the funding target of the projects but did not explain how the money would be used. The researchers therefore had to ask specific questions about the usage of the money and the concept of Namstarter.

4.4.3. A tech mediator collective

The content of this session was led by the participants. The researchers had anticipated that the tech mediator would be a single person. However, the participants expressed that rather than having only one community member acting as a tech mediator, the tasks and responsibilities could be divided among all community members participating in the training.

The division of roles was approached through the crowdfunding advisor persona that was created earlier the same day. Each responsibility listed for the created persona was carefully divided into different roles in the committee. Eventually, the committee came to have eight members: an administrator, secretary, treasurer, chairperson, community relations person, marketing and communications manager, advisor, and business developer. In addition, the committee would have an advisory board with external participants. Discussion on the committee roles continued even after the session.

4.5. Post-workshop

Right after the workshops, the campaign page was still missing photos, the rendered video, and the banking information of the campaign manager. Since he did not have a bank account, the researcher team agreed that local university researchers would help to set up a bank account and add the missing content to the campaign page.

In addition to the training of the tech mediators, an outcome of the workshops was that the Havana group created an independent closed corporation to manage Namstarter. They also chose directors for their various closed corporations, all of whom were community members. Furthermore, they registered their closed corporation, Havana Entrepreneurs CC, with the Business and Intellectual Property Authority, for which they chose six directors, comprising the developer and Havana community members. The roles in closed corporation were assigned reflecting the interests and previous unofficial roles of the members. For example, the member who enjoyed working with others took a position as community manager. Similarly, the role of chairman went to the community member who had been in a community spokesperson role previously. A bank account was then created to register the closed corporation, receive donations, and facilitate online payments. The system developer and community members met twice to implement changes on the Namstarter platform such as updating contact details and campaigns.

We also observed interpersonal tensions among the committee members, especially among the more experienced persons. They felt that there was a disparity between the effort some individuals had been put into planning of the committee, and the power that they acquired in it. It was decided that one of the local university coordinators would attempt to settle disputes, considering that the operation of the tech mediator might be affected.

Eventually, the crowdfunding campaign was completed and ready to be uploaded. However, just as we were about to upload the campaign, the crowdfunding policy was changed on the chosen global platform to no longer support payments to Namibia. Also, none of the competing platforms supported Namibian campaigns. As a result, the campaign has still not been uploaded yet global platforms’ constraints are monitored while alternative financial options in Namibia are explored.

5. Description of tech mediator

The aim of this paper was to present a potential workable solution for the SSEs in the global south to overcome the exclusion by the global crowdfunding platforms. Based on our fieldwork, the description of the tech mediator’s role is presented in .

5.1. Tech mediator collective’s role

Deviating from the idea of an individual, the community members insisted that the tech mediator should be a collective of people with assigned roles. This was motivated by reducing the risk that tech mediators might not be available and making the burden on individual tech mediators more manageable.

The role of the tech mediator collective is to work with local SSEs to help community members utilise global digital services. The newly formed tech mediator collective emphasised the proactive role they thought they should fulfill in their communities, in line with the three roles identified. It was agreed that, first, they should actively spread information of existing digital services among SSEs, second, they should understand the context of local entrepreneurs, and third, they may recommend new services to solve the issues that community members might have.

For local communities, the tech mediators represent an entry point to global digital services that are not truly available for these communities. The tech mediators interact with both digital services and their local community, translating the needs of the locals into the ‘language’ of global services. The tech mediators are also trained in using global services and thus may assist their local peers in accessing the services if the user interfaces are difficult to use. A local platform consists of digital tools that the mediators employ in managing the local communities’ activities. These services should help the tech mediators manage their project portfolio and the local entrepreneurs who run these projects. In our case, the Namstarter serves as a project repository that will be linked to the crowdfunding campaign on global platforms, providing potential funders with more information on the projects. The collective has assigned one person to the maintenance of local services and one for global services.

The tech mediators also need to understand the context in which potential funders operate, as well as the latter’s view of projects on Namstarter, for example. During the campaign development, we discussed how the content they want to publish will likely be perceived by someone from the northern hemisphere. They learned the basics of mainstream persuasive media content creation. For digital platforms that require interaction between SSEs in the global south and users in the global north, the tech mediators need to guide community members on effective cross-cultural communication so that they can use the platforms effectively for their endeavours. However, becoming fully cross-culturally fluent is practically impossible for the tech mediators, as they will likely have only limited opportunities to directly communicate with potential funders in the global north.

Most importantly, tech mediators act as an access point to global platforms for local SSEs. They need to directly interact with the global platforms in order of representing their communities on international digital arenas.

5.2. Tasks of the tech mediator collective

As it was decided in the planning of the design intervention, the role of Namstarter would be a role of business incubator offering funding and services for the entrepreneurs in their portfolio. The Namstarter board would need to select promising entrepreneurs who would benefit the most from the possibility to use digital services and to receive seed funds. As has been demonstrated in , the individual SSEs are unlikely to be able to access and to utilise global digital services without help from the tech mediators. The trained tech mediators as a collective would form the Namstarter board, and be the ones who help the SSEs in connecting to available digital services.

Three types of tasks for the tech mediator collective emerged during the conceptualisation sessions. The tasks were community management, technology advice, and administration.

Those in community management roles should work with the community to facilitate the usage of digital services. These facilitating responsibilities might include organising workshops to spread information and entrepreneurial attitudes in the community, helping community members to meet requirements for using digital platforms (e.g. opening email accounts and bank accounts), and organising computers for locals.

Those in technology advisor roles should proactively search for new services, introduce these services to the community they are serving, and provide technical support for the community members to use these services. The technology advisors should also help community members to create suitable content for the platforms.

Finally, administrative duties in tech mediator collective include managing the money raised by crowdfunding campaigns, managing community member lists, and negotiating with other local stakeholders.

If the crowdfunding campaign would have been published, and it would have gathered some funds, the tech mediator collective and Havana Entrepreneurs CC that was formed to manage it would have been distributing the money to the entrepreneurs in the portfolio. The funds would have also allowed Namstarter to start developing its own processes of helping the SSEs by offering them an access to otherwise unavailable digital services.

5.3. Future activities

The Havana tech mediators did not develop a comprehensive set of skills to master all assigned roles independently. For example, they need more training on how to use digital platforms to autonomously publish campaigns. Equally, they are currently not equipped with training skills to teach other community members. We will continue working with the collective to realise their full potential as tech mediators.

We are equally planning to expand on the offering of digital services beyond crowdfunding. We aspire to make the tech mediators a gateway for digital services for the individuals in the community. Although we ultimately were not able to find a suitable solution for crowdfunding, as our campaign was excluded from the global platform, there are also other digital services that could be beneficial for the SSEs in Havana. For example, there are educational resources freely available on the Internet. We wish to use the tech mediator model to make those services available for the same SSEs we wished to help with crowdfunding.

Tech mediator collectives are equipped to establish local capabilities. This includes access to financial services, which has been difficult to realise (Deen-Swarray, Ndiwalana, and Stork Citation2013). For instance, tech mediator collectives will be able to acquire funds for entrepreneurs without bank accounts through their collective bank account. Tech mediator collectives can also use their communal bargaining power to provide access to computers.

One of the keys in interacting with the communities is to ensure that the community members who wish to adopt new services do not become exploited by the owners or other users of the service. While this viewpoint was not considered critical in crowdfunding, we have to consider it when we introduce new services for the communities.

Besides the exploitation from the platforms side, it is possible, that the other community members could face exclusion or other forms of malpractice from the tech mediators. Although we think that it was important to train local community members to be tech mediators instead of outsiders, these tech mediators inevitably bring their past relations with the other community members into the role. The tech mediators might have their own agenda in the tech mediator role. The tech mediator being a collective rather than an individual should help ease potential tensions. Also, our research team has representatives in the company board with a mandate to solve potential conflicts.

6. Discussion

6.1. Co-creating local tech mediation

Based on our empirical work on the local crowdfunding site and the attempt to integrate with the global platforms we maintain the necessity of a human mediator in the community. The literature has presented various reasons why digital services are not truly available globally, even when they are freely accessible via the Internet (Pankomera and van Greunen Citation2019). Replacing the international digital interface with local human one appears promising to making the services more accessible.

Our experience emphasises the importance of the interaction between the researchers and the participants. The context of this design, international crowdfunding platforms, is a distant concept for the SSEs in Havana. Thus, it is likely that the community would not have been appropriated the platforms for their own needs without a lead from outside. However, after clarifications the local entrepreneurs took lead in the conceptualisation of the ‘tech mediator collective’ suitable for the locale.

Building on the work of Kambunga, Winschiers-Theophilus, and Goagoses (Citation2018), who have explored the importance of local champions in the adoption of digital services, we confirm the importance of tech mediators being locals of the community. The local tech mediators should help community members to trust and appreciate digital services, lack of which has been mentioned as an issue (Gbadegeshin et al. Citation2019; Lafraxo et al. Citation2018). The conceptualisation of the model was conducted with a small participant group in a relatively short period of time. The participants were carefully selected, being community members who have been engaged in numerous similar activities prior to this study and demonstrated their commitment to community development and technology adoption. We found this prior built relationship and trust with the participants to be essential in our work, as it made the effective communication with the participants possible. The participants also had basic computer skills which enabled us to proceed in the technical training in quicker pace.

6.2. Exclusion of global South players

The functioning of global platforms are not dependent on the possibilities of the users in the fringes (Nicholson et al. Citation2019), and as our example demonstrates, dependence on the global platforms might lead to problematic situations (Langley and Leyshon Citation2017). Our attempt to publish the final Namstarter campaign on a prior identified global platform, failed, as the platform in question changed their terms of use, no longer allowing Namibian players to participate. The local entrepreneurs had invested substantial effort and time in preparing the campaign, which was unexpectedly excluded from the global platform.

The exclusion of users from the global south by the global platforms is problematic, as the global platforms have nearly monopolised the crowdfunding market, leaving little room for alternative, more inclusive platforms to grow. Our attempt to use crowdfunding platforms to empower the Namibian SSEs appears to be in dead-end. Attempts to either influence the policies of global platforms, or to try to challenge them with a local alternative are well beyond the resources that we (or most academic driven co-design projects) have. Currently, it appears that despite our best efforts global crowdfunding cannot be used to support the Havana entrepreneurs.

Crowdfunding would be a beneficial service for the entrepreneurs in the global south, who often lack an access to resources such as banking. Crowdfunding, as all digital services, should not be treated as wholly non-problematic silver bullet that fixes all the problems. Over-promotion of entrepreneurship as a way of shifting the responsibility of fixing the economical problems from government to individuals (Jeffrey and Dyson Citation2013). However, we worked with entrepreneurs, who wish to develop their businesses with all the tools. They would deserve an access to the same global crowdfunding services that are used by their peers in the global north. For this community, an exclusion from global platforms is a larger problem than possible exploitative features of the platforms would be.

Overall, the discussion regarding the exploitative features of platform capitalism has centred too much on the global north. For example, services such as Amazon Mechanical Turk and Uber have been heavily criticised for their tendency to force the workers into the role of an independent contractor. Independent contractors enjoy very little benefits and protections compared to regular, salaried employments. However, in Namibia, 57% of workers are part of the informal economy (Namibia Statistics Agency Citation2018), which is described by these same features issues (ILO Citation2018). If an informal economy worker, who is waiting at a roundabout for someone to possibly give them a temporary job, changes the method of finding jobs to using digital applications, would they then be considered to be in a more disadvantaged position within global power structures?

Gloess et al. has invited designers to make informed decisions on the labouring of the future (Glöss, McGregor, and Brown Citation2016). Co-design has perfect tools for understanding the needs of the users in a nuanced way. Co-design also has history in improving the labour conditions. In this paper, we have attempted to use the global platforms in a beneficial manner with the SSEs in Namibia. Multi-sided, global platforms have been little discussed in co-design literature. As these platforms are going to be a part of the digital service landscape the people face in their daily lives and pursues of livelihoods, we wish to invite our fellow co-designers to try to find ways to make them more beneficial and less exploitative for their users. In section 2 we presented a research question ‘How co-design can contribute to a workable solution on the usage of multi-sided digital platforms by global south users?’. Thus, in this paper, we have demonstrated how we have used a co-design approach to develop and define a tech mediators position, who in theory could facilitate the beneficial usage of global multi-sided platforms in disadvantaged communities.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented a workable model for making global digital services more accessible to SSEs in the global south. Our results can be used to inform practice, policy-making and scientific modelling. Our identification of gaps (socio-cultural, accessibility & adoption, usage, and integration) preventing the effective interaction between entrepreneurs in the global south, international crowdfunding services, and funders provides a foundation for systematic elaboration of sustainable solutions.

The tech mediator model that has been conceptualised and presented in this paper utilises trained peers as the smart human interface for accessing global platforms. The tech mediator with access to global digital services helps local entrepreneurs in communities to connect to global platforms. The tech mediator also has an understanding of the cultural contexts of potential funders to help facilitate communication with them. The model should be applicable for various types of practitioners, including platform managers wishing to operate in the global south and those who wish to independently help local communities utilise global digital services.

Global digital services offer opportunities that can be harnessed for advancing human development in emerging economies. The interaction between users in the global south and the global north provide possibilities that cannot be replicated in more localised solutions. However, these services are often not truly available for potential users in the global south. We were unable to successfully upload the crowdfunding campaign we had co-designed with the local community, as the global platform changed their policies to exclude users from Namibia.

The role of digital platforms in the global south has recently become increasingly topical in academic discussion (Koskinen, Bonina, and Eaton Citation2019). We see that the digital platforms could be part of the solution for the small-scale entrepreneurs who wish to improve their livelihoods in the global south. However, we have also demonstrated that by excluding the users in global south, cannot be trusted as the whole solution. These platforms operate globally, and the benefits to the users in the peripheries might be, even inadvertently, forgotten. The international platforms will be part of the digital landscape in near future. Both better designs from designers, and regulations are needed to ensure more equitable future for platform users.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Havana community members for their long-term engagement. The local inclusive collaborative tech innovation hub has financially and in kind supported the research activities in Namibia. KAUTE-foundation has funded the first author of this paper. Business Finland has supported the creation of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agrawal, A., C. Catalini, and A. Goldfarb. 2014. “Some Simple Economics of Crowd- Funding.” In Innovation Policy and the Economy, edited by J. Lerner and S. Stern, 63–97. Vol. 14. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Ahmed, S. I., N. J. Bidwell, H. Zade, S. H. Muralidhar, A. Dhareshwar, B. Karachiwala, C. N. Tandong, and J. O’Neill. 2016. “Peer-to- Peer in the Workplace: A View from the Road.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’16, 5063–5075. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Arvila, N., H. Winschiers-Theophilus, P. Keskinen, R. Laurikainen, and M. Nieminen. 2020. “Enabling Successful Crowdfunding for Entrepreneurs in Marginalized Communities.” In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Academic Mindtrek, 45–54, Vol. 1. New York, NY: ACM. http://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3377290.3377303

- Avram, G., J. H. J. Choi, S. D. Paoli, A. Light, P. Lyle, and M. Teli. 2019. “Repositioning CoDesign in the Age of Platform Capitalism: From Sharing to Caring.” CoDesign 15 (3): 185–191. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1638063.

- Bassetti, C., M. Sciannamblo, P. Lyle, M. Teli, D. P. Stefano, and D. A. Antonella. 2019. “Co-designing for Common Values: Creating Hybrid Spaces to Nurture Autonomous Cooperation.” CoDesign 15 (3): 256–271. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1637897.

- Belleflamme, P., T. Lambert, and A. Schwienbacher. 2013. “Crowdfunding: Tapping the Right Crowd.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (5): 585–609. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003.

- Best, J., S. Neiss, R. Swart, A. Lambkin, and S. Raymond. 2013. Crowdfundings Potential for the Developing World, 1–102. Washington, DC: infoDev.

- Boateng, R., R. Hinson, R. Galadima, and L. Olumide. 2014. “Preliminary Insights into the Influence of Mobile Phones in Micro-trading Activities of Market Women in Nigeria.” Information Development 30 (1): 32–50. doi:10.1177/0266666912473765.

- Brown, A. V., J. H. J. Choi, and J. Shakespeare-Finch. 2019. “Care Towards Posttraumatic Growth in the Era of Digital Economy.” CoDesign 15 (3): 212–227. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631350.

- Carroll, J. M., and J. Beck. 2019. “Co-designing Platform Collectivism.” CoDesign 15 (3): 272–287. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631353.

- Cordova, A., J. Dolci, and G. Gianfrate. 2015. “The Determinants of Crowdfunding Success: Evidence from Technology Projects.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 181: 115–124. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.872.

- Deen-Swarray, M., A. Ndiwalana, and C. Stork. 2013. “Bridging the Financial Gap and Unlocking the Potential of Informal Businesses through Mobile Money in Four East African Countries.” In CPRsouth8/CPRafrica2013 …, 1–15. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2531859

- Fehrer, J. A., and S. Nenonen. 2019. “Crowdfunding Networks: Structure, Dynamics and Critical Capabilities.” Industrial Marketing Management88, no. February: 1–16.

- Gbadegeshin, S. A., S. S. Oyelere, S. A. Olaleye, I. T. Sanusi, D. C. Ukpabi, O. Olawumi, and A. Adegbite. 2019. “Application of Information and Communication Technology for Internationalization of Nigerian Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises.” Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 85 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/isd2.12059.

- Gerber, E. M., and J. Hui. 2013. “Crowdfunding: Motivations and Deterrents for Participation.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 20 (6): 1–32. doi:10.1145/2530540.

- Glöss, M., M. McGregor, and B. Brown. 2016. “Designing for Labour: Uber and the On-Demand Mobile Workforce.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’16, 1632–1643. New York, NY: ACM Press.

- Goagoses, N., A. P. Kambunga, and H. Winschiers-Theophilus. 2018. “Enhancing Commitment to Participatory Design Initiatives.” In Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference: Short Papers, Situated Actions, Workshops and Tutorial-Volume 2, 14. Hasselt, Belgium: ACM.

- Hagiu, A. 2014. “Strategic Decisions for Multisided Platforms.” MIT Sloan Management Review 55 (2): 71–80.

- Hagiu, A., and J. Wright. 2015. “Multi-sided Platforms.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 43: 162–174. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.03.003.

- Hira, A. 2017. “Profile of the Sharing Economy in the Developing World: Examples of Companies Trying to Change the World.” Journal of Developing Societies 33 (2): 244–271. doi:10.1177/0169796X17710074.

- ILO. 2018. “Informality and Non-standard Forms of Employment.” Technical Report, February. http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2018/g20paperonnseandformalizationilo.pdf

- Jeffrey, C., and J. Dyson. 2013. “Zigzag Capitalism: Youth Entrepreneurship in the Contemporary Global South.” Geoforum 49: R1–R3. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.01.001.

- Kambunga, A. P., H. Winschiers-Theophilus, and N. Goagoses. 2018. “Reconceptualizing Technology Adoption in Informal Settlements Based on a Namibian Application.” In Proceedings of the Second African Conference for Human Computer Interaction on Thriving Communities - AfriCHI ’18, 1–10. New York, NY: ACM Press. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=3283458.3283468

- Kang, M., Y. Gao, T. Wang, and H. Zheng. 2016. “Understanding the Determinants of Funders’ Investment Intentions on Crowdfunding Platforms: A Trust-based Perspective.” Industrial Management and Data Systems 116 (8): 1800–1819. doi:10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0312.

- Keskinen, P., and H. Winschiers-Theophilus. 2020. “Worker Empowerment in the Era of Sharing Economy Platforms in Global South.” In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference on Exploratory Papers, Interactive Exhibitions, Workshops - PDC ’20. Manizales, Colombia.

- Keskinen, P., N. Arvila, H. Winschiers-Theophilus, and M. Nieminen. 2020. “The Effect of Digital Community-Based Tourism Platform to Hosts Livelihood.” In Evolving Perspectives on ICTs in Global Souths - 11th International Development Informatics Association Conference, IDIA 2020, Macau, China, March 2527, 2020, Proceedings, 3–16. Macau, China: Springer International Publishing. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-52014-41

- Kim, M.-S. 2005. “Culture-Based Conversational Constrains Theory: Individual- and Culture-Level Analyses.” In Theorizing About Intercultural Communication, edited by W. B. Gudykunst, 93–117. Chap. Culture-Ba. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Kim, Y., A. Shaw, H. Zhang, and E. Gerber. 2017. “Understanding Trust amid Delays in Crowdfunding.” Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW 1982–1996. Portland, Oregon, USA.

- Koskinen, K., C. Bonina, and B. Eaton. 2019. “Digital Platforms in the Global South: Foundations and Research Agenda.” In ICT4D 2019: Information and Communication Technologies for Development. Strengthening Southern-Driven Cooperation as a Catalyst for ICT4D, edited by P. Nielsen and H. C. Kimaro, 319–330. Cham: Springer International Publishing. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-18400-126

- Kuo, Y. F., and C. H. Wu. 2014. “Understanding the Drivers of Sponsors’ Intentions in Online Crowdfunding: A Model Development.” 12th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia, MoMM 2014, 433–438. Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- Lacan, C., and P. Desmet. 2017. “Does the Crowdfunding Platform Matter? Risks of Negative Attitudes in Two-sided Markets.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 34 (6): 472–479. doi:10.1108/JCM-03-2017-2126.

- Lafraxo, Y., F. Hadri, H. Amhal, and A. Rossafi. 2018. “The Effect of Trust, Perceived Risk and Security on the Adoption of Mobile Banking in Mo- Rocco.” In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 497–502, Vol. 2. Funchal, Madeira, Portugal: SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications. http://www.scitepress.org/DigitalLibrary/Link.aspx?doi=10.5220/0006675604970502

- Langley, P., and A. Leyshon. 2017. “Capitalizing on the Crowd: The Monetary and Financial Ecologies of Crowdfunding.” Environment and Planning A 49 (5): 1019–1039. doi:10.1177/0308518X16687556.

- Light, A., and A. Seravalli. 2019. “The Breakdown of the Municipality as Caring Platform: Lessons for Co-design and Co-learning in the Age of Platform Capitalism.” CoDesign 15 (3): 192–211. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631354.

- Light, A., and J. Briggs. 2017. “Crowdfunding Platforms and the Design of Paying Publics.” In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’17, 797–809. New York, NY: ACM Press. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=3025453.3025979

- Masele, J. J., and R. Matama. 2019. “Individual Consumers’ Trust in B2C Automobile Ecommerce in Tanzania: Assessment of the Influence of Web Design and Consumer Personality.” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries86, no. June: 1–15.

- Meyskens, M., and L. Bird. 2015. “Crowdfunding and Value Creation.” Entrepreneurship Research Journal 5 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1515/erj-2015-0007.

- Mitra, T., and E. Gilbert. 2014. “The Language that Gets People to Give: Phrases that Predict Success on Kickstarter.” In CSCW ’14: Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work & social computing, Baltimore.

- Möhlmann, M., and A. Geissinger. 2018. “Trust in the Sharing Economy: Platform- Mediated Peer Trust.” In Cambridge Handbook of the Law of the Sharing Economy,edited by N. M. Davidson, Michèle Finck, University of Oxford, John J. Infranca, 27–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-the-law-of-the-sharing-economy/trust-in-the-sharing-economy/296C10360E7CC4DDB6B2B915AA3732AC

- Mollick, E. 2014. “The Dynamics of Crowdfunding: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.005.

- Namibia Statistics Agency. 2018. “The Namibia Labour Force.” Technical Report.

- Nicholson, B., P. Nielsen, J. Saebo, and S. Sahay. 2019. “Exploring Tensions of Global Public Good Platforms for Development: The Case of DHIS2.” IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 551: 207–217.

- Ongwere, T. 2015. “Self-actualization of Unemployed Youth through Participatory Service Design.”

- Osei-Assibey, E. 2015. “What Drives Behavioral Intention of Mobile Money Adoption? The Case of Ancient Susu Saving Operations in Ghana.” International Journal of Social Economics 42 (11): 962–979. doi:10.1108/IJSE-09-2013-0198.

- Pankomera, R., and D. van Greunen. 2019. “Opportunities, Barriers, and Adoption Factors of Mobile Commerce for the Informal Sector in Developing Countries in Africa: A Systematic Review.” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, no. May 2018: e12096. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/isd2.12096

- Pekmezovic, A., and G. Walker. 2016. “The Global Significance of Crowd-funding: Solving the SME Funding Problem and Democratizing Access to Capital.” William & Mary Business Law Review 7: 347. https://academic.oup.com/socpro/articlelookup/doi/10.1525/sp.2007.54.1.23

- Poderi, G. 2019. “Sustaining Platforms as Commons: Perspectives on Participation, Infrastructure, and Governance.” CoDesign 15 (3): 243–255. doi:10.1080/15710882.2019.1631351.

- Srnicek, N. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: John Wiley & Sons. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=2HdNDwAAQBAJhl=enpg=GBS.PR2

- Ting-Toomey, S. 2005. “The Matrix of Face: An Updated Face-Negotiation Theory.” In Theorizing About Intercultural Communication, edited by W. B. Gudykunst, 71–92. Chap. The Matrix. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., D. G. Cabrero, S. Chivuno-Kuria, H. Mendonca, S. S. Angula, and L. Onwordi. 2017. “Promoting Entrepreneurship amid Youth in Windhoeks Informal Settlements: A Namibian Case.” Science, Technology and Society 22 (2): 350–366. doi:10.1177/0971721817702294.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., P. Keskinen, D. G. Cabrero, S. Angula, T. Ongwere, S. Chivuno-Kuria, H. Mendonca, and R. Ngolo. 2015. “ICTD within the Discourse of a Locally Situated Interaction: The Potential of Youth Engagement.” In Beyond development. Time for a new ICT4D paradigm? Proceedings of the 9th IDIA conference, IDIA2015, 52–71. Zanzibar, Tanzania.

- Wood, A. J., M. Graham, V. Lehdonvirta, and I. Hjorth. 2019. “Networked but Commodified: The (Dis)embeddedness of Digital Labour in the Gig Economy.” Sociology 53 (5): 931–950. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0038038519828906

- World Bank. 2015. “Crowdfunding in Emerging Markets: Lessons from East African Startups.” https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23820

- World Bank. 2016. World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Wresch, W., and S. Fraser. 2011. “Persistent Barriers to E-commerce in Developing Countries.” Journal of Global Information Management 19 (3): 30–44. http://services.igiglobal.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/jgim.2011070102