ABSTRACT

This paper investigates how designer-led co-making and civic pedagogy can increase urban learning and resilience through transversal relationalities. We explore two case studies in which designers work with communities to run civic pedagogical projects, using co-making as a tool: Collective Design Practice, in Mumbai, India, co-produced with Muktangan school; and the Eco Nomadic school, situated in Europe. We use theories of agency, correspondence and care to compare the roles of designers and identify the particular moments (or “knots”) where resilience is created. Situated in the Global South and North, respectively, we identify, compare and discuss the research methods and processes used. The research asks how pedagogically supported and designer-led co-making can increase resilience in different parts of the world, particularly when it relates to everyday life. We propose that the civic pedagogy of co-making can be powerful: through it people can have more agency to improve social relations and politics of place; it can make tangible and more understandable political statements and make physically evident the benefits of practice; it can build civic practices of resourcefulness and resilience.

1. Introduction

To co-make is to make something together. It is not only designing together but also the fabrication and physical implementation of that which is made, a shared social and spatial occasion; furthermore, co-making has the potential to create social and spatial change. “Making” has been offered as part of a trio of activities, including “telling” and “enacting” as part of a participatory design methodologies framework (Sanders, Binder, and Brandt Citation2013). But co-making adds a particular layer to making by involving multiple people in decision-making and action, a step beyond design. As a term, it has been used in the fields of design and education. In design, co-making has been described as “a social and material entanglement” and “collaborative issue making”, related to Participatory Design practice (Popplow Citation2016); in education, its use is in relation to constructivist and constructionist approaches to learning (Sadka and Zuckerman Citation2017). As a practice, it is also increasingly used in a range of fields such as fashion (McQuilten and Spiers Citation2020), anthropology (Levick-Parkin Citation2018), and story-making (Liu and Lan Citation2021).

This paper looks at co-making from a new angle and asks: how can co-making contribute to civic pedagogical processes to help communities build resilience? What roles can designers play? Both authors are practice-led researchers who have used a number of conscious processes to set up pedagogical urban making projects compared here in two case studies. The research focuses on co-making which is designer-led; that is to say that the co-making activity has been curated or organised by a designer, with the aim of creating strategic output, to involve a range of participants. It also focuses on co-making towards civic pedagogy, which consists in our case in learning that involves an engagement with (and critique of) the urban landscape. Our understanding of co-making is that it is distinct from co-design. Co-design involves the planning of fabrication and implementation, while co-making is the fabrication process itself. Co-design as a process has increased in popularity in recent years, in relation perhaps to austerity but also as a reaction to inefficient public services in need of reform and an activation of citizens’ rights to and need for resilient cities (Petcou and Petrescu Citation2015). Further, co-design methods have been experimented with, and widely analysed and identified as means of spatial commoning and spatial learning (Manzini and Rizzo Citation2011; Birch et al. Citation2017; Baibarac and Petrescu Citation2019; Parnell, Cave, and Torrington Citation2008) particularly in the urban realm. We proposed understanding co-making as a component of the co-design methodology, an activity that is sometimes, but not always, used as a stage of co-design projects. We also use the term co-production in addition to co-making and co-design: we understand co-production to be at a higher organisational and strategic level, a collective practice of getting things done (Bell and Pahl Citation2017).

In the last two decades an increasing number of projects have involved communities in coming together to manually create artefacts as means of collective expression; from grassroot activities to research methods of engagement and artist collaborations with the public. Often these projects encourage civic engagement, rights and responsibilities to the city. We have chosen two case studies for comparison due to their differing order of activity: One begins with co-making, and the other begins with co-design. One is based in the Global North, and the other the Global South. We ask: How are these processes of co-making civic pedagogy design led? What are the (new) roles for designers? How do the designers engage in a reflexive practice? How do the designer roles compare in different contexts, especially in the Global South and North? How do they work at the scale of the neighbourhood or at wider scales? Who are the actors that make these processes resilient?

Two long-term approaches are examined here: a collective design practice (CDP) in Mumbai, India, with Muktangan School over 6 years and the Eco Nomadic School (ENS) in Europe over 10 years. We have used project data that includes participants roles, materials, localities, activities, and methods; the data has been collected from both projects over the course of the research, and compared using a table (see ). What is new about this research is that it asks how co-making creates social and ecological relations and enhances civic resilience in different parts of the world, particularly when it is embedded in everyday life. We propose that co-making involves tacit civic pedagogical processes: through it people can have more say and agency to improve social relations and politics of place; make more understandable political statements; and make physically evident the benefits of design practice. Collective intelligence grows through the process of co-making (Ingold Citation2013) and making together can help build community.

Table 1. This table identifies designers roles as agents, (social) makers, correspondents and caretakers, across the Collective Design Pedagogy and Eco Nomadic School projects.

We investigate the roles of designers in such co-making processes in relation to four theories: First, co-making as a form of agency, a series of decisions to act differently (Giddens Citation1984); second, as part of a Community of Practice (Wenger Citation2010) that enhances civic learning; third, using “correspondence”(Ingold Citation2013) to build relationalities; and fourth, in relation to care-taking (Trogal Citation2017a; Tronto Citation2020; Fitz and Krasny Citation2019) through spatial production. We discuss different approaches of co-making in Europe, UK, US (Global North), and India (Global South), and then discuss the two case studies using the four theories to learn from their similarities and differences.

Finally, we summarise our arguments and consider the wider implications of co-making as part of civic pedagogies towards resilient engagement, discussing the role of designers in these processes.

2. Civic pedagogies of co-making

Along with a rise in participatory practices in design and architecture since the 1960s, contemporary terms such as “hands-on urbanism” (Krasny Citation2012) and “DIY activist culture” (Petrescu Citation2005) have grown out of a continuous dissatisfaction with the current level of design democracy and an environment that does not respond to community needs. An inclusive design practice that prioritises social and ecological care is developing. Co-making methods are often used as forms of inclusive civic design engagement (Jones et al. Citation2005; Rice Citation2018) because of their capacity to physically bring people together through resource-light, DIY and hands-on urbanist practices, creating tangible collective responses to place. Often these methods are instigated and facilitated by socially minded designers (Julier and Kimbell Citation2019), with a view to engaging the public through the creation of something (a map, an artefact) that is in some way connected to their locality. These methods can also be used by designers to help communities develop resilience (Petrescu, Petcou, and Baibarac Citation2016). This builds on a growing movement of urban designers who seek to contest mainstream disciplinary practices, looking to redefine design while searching for greater agency to “recalibrate” power relations with renewed engagement (Boano and Talocci Citation2014) and to pay attention to the ways this engagement take place (Trogal and Wakeford CitationForthcoming).

Today, practices of co-making often involve digital elements – whether using video or audio for documentation and design development, or 3d scanners and printers for making forms (Torrey, Maloy, and Edwards Citation2018). There are also increasing practices of repairing and mending; people are trying to be more responsible and sustainable, often in a democratic or grassroots way to respond to the worsening climate crisis. Growing one’s own food and increased care and attention for the environment have a part to play in this expanded DIY culture. In the field of Urban Studies, co-making can contribute to both informal and formal (civic) pedagogical processes by creating platforms for situated knowledge sharing, transmission of knowledge between individuals and groups helping communities build flexible, diverse, and adaptable everyday resilience through tacit learning. We use the term resilience to mean the building of strength and flexibility, diversity and adaptability of action, including the public in the co-production of the shared environment and allowing learning and agency to develop (Carli Beatrice Citation2016). We argue designers can orient civic pedagogies towards resilience by adopting resourceful, adaptable and re-usable practices.

Civic pedagogies are broadly defined as learning processes that involve participants in managing or producing the socio-spatial environment. Civic pedagogy is almost always a critical pedagogy (Freire Citation1970; Giroux Citation2004), a building of awareness or “conscientisation” through situated practices. As a critical educational planning tool, it can be traced back to the work of Scottish planner Patrick Geddes in the early 1900s, Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich (De-schooling Society Citation1971), and British educators Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson (Streetwork Citation1973); and the pedagogies of Rabindranath Tagore (Siksha Satra Citation1936) and Mahatma Gandhi (Basic Education Citation1947) in India. Civic pedagogy also has a feminist, decolonising and anti-racist agenda (bell hooks Citation2003; Frediani et al. Citation2019). Dutch Educator Gert Biesta identifies three different “modes” of public pedagogy: (1) pedagogy for the public (instruction); (2) pedagogy of the public (conscientisation); and (3) pedagogy that enacts a concern for publicness (interruption) (Biesta Citation2012). Co-making as a civic pedagogical method can also be seen through this three-part lens: it can be instructed but not necessarily critical; “conscientising”, or raising awareness; and interrupting the status quo to increase meaningful co-agency. We argue that co-making as a collaborative civic pedagogy can increase public agency through tacit everyday relationalities and activities.

3. Agency, communities of practice, correspondence and care in civic pedagogies of co-making

We have identified a number of theoretical concepts that can support our hypothesis about the role of designers in orienting civic pedagogies of co-making towards resilience. In these pedagogies, “agency” plays an important role, both in the instigation of the project by the designer and as a learning output for participants. We use Anthony Giddens’s interpretation of the concept: it is the ability to decide whether or not to intervene in the world in order to “make a difference”, or exercise some sort of power (Giddens Citation1984, 14). Through this understanding, there are particular implications on architecture, and the role of the architect, where “the lack of a predetermined future is seen as an opportunity and not a threat” (Schneider and Till Citation2009). Agency can create opportunities for civic learning, which is key in resilience. As Rob Hopkins puts it, “resilience is not just an outer process: it is also an inner one, of becoming more flexible, robust and skilled” (Hopkins Citation2009, 15).

Social anthropologist Jean Lave has long studied situated civic relationalities, notably how learning and knowledge is transferred between people and things through practices of making; she found knowledge is contextual and that there exist communities of learning linked to place. Along with Etienne Wenger, Lave defined the term “situated learning”, referring to the situation of an individual who acquires skills through practice, leading to being part of a “community of practice” (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). Situated learning “takes as its focus the relationship between learning and the social situation in which it occurs” (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). The human relationalities present in civic pedagogies can be described as “communities of practice”, in which “learning becomes an informal and dynamic social structure among the participants”. (Wenger Citation2010)

Co-making, can at once be a situated learning, one that creates new relationships between people and things, but also has the potential to increase relationships with place and build a sense of empowerment in the urban realm. The “co” in co-making increases the capacity of the making process to be a producer of situated commoning, and therefore resourcefulness and resilience (Petrescu, Petcou, and Baibarac Citation2016).

There are further productive interactions at play: to think through the relationalities, anthropologist Tim Ingold’s theory of correspondence adds a reflexive lens with which to study the potential for transversal learning. Co-making can be seen as a kind of “correspondence” on a micro and macro level, between individual people and large groups, between people and things, places, regions, and even nations. Ingold argues that “correspondence” - understood as the oscillating activities in a relationship between two people, or a person and an object – is transformative; further, material can be a subject of inquiry and an agent of knowledge (Hofverberg and Kronlid Citation2018). Some have argued that human-material relationships change our habits and lifestyles (Chanchra Citation2016), and others have explored human-material relationships within craft specifically: craft knowledge as enabler of self-reliance (Von Busch Citation2013), human-material craftsmanship as a consistent problem-finding and problem-solving activity (Sennett Citation2008) or even that manifests citizenship (Orton-Johnson Citation2014).

Through “correspondence”, two parties create something new derived from parts of themselves (Ingold Citation2013). Ingold illustrates these interactions as “knots”: “A knot is formed when a strand such as of string or yarn is interlaced with itself or another strand and tightened. … in a world where things are continually coming into being … knotting is the fundamental principle of coherence”. (Ingold Citation2017, 10) suggesting knots and knotting joins born out commitment and attention (Ingold Citation2017, 23–24) may be central to understanding social relationships (Ingold Citation2017, 11). In our case study of civic relationalities of co-making, we argue that designers can enable “knot”-making via pedagogic processes. Further, knots can be key to resilience, specifically when understood as “resourcefulness” (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2013).

This “knot”-making knowledge can be compared to the Indian concept of jugaad, useful to understand processes of social/spatial/economic negotiation to spontaneously respond and tactically plan resourcefulness. The Hindi word jugaad means “a flexible approach to problem-solving that uses limited resources in an innovative way” (Oxford Dictionary Citation2018). Jugaad means cobbling together, street smarts, hustle, negotiation, working around the system, and finding loopholes (Radjou, Prabhu, and Ahuja Citation2012). The practice of jugaad has developed in reaction to formal or existing systems that are difficult to navigate, or that are restrictive to daily life. It is a habitual practice used in many situations, as a form of resilience. It is a translocal technique and an informal coping strategy that highlights the particular entrepreneurial, self-sufficient and collective character of Indian cities, playing a ‘fundamental role in constituting the urban (especially in the “+global south”)’ (McFarlane Citation2012).

The fourth theory that we use to investigate our case studies refers to “care”. Feminist scholars Joan Tronto and Berenice Fischer notably define care as: “a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our world so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment … ” (Tronto and Fisher Citation1990). In other words, care underpins resilience. Care as a spatial concept has been investigated by architectural scholar Trogal (Citation2017a) who calls it “a form of spatial production”. She explores “practices of collective care” that are specifically “beyond the proximate”, asking how care can make transversal connections in spatial practice, and create connections across diverse social and cultural groups, and hierarchies (Trogal (Citation2017a)).

Further, Tronto’s exploration of care as a design practice (Tronto Citation2020) argues that if architecture is a reflection of power, “using care as a critical concept requires a fundamental reorientation of the discipline”. Her critique of architects and designers as often caring about ‘the wrong things … using “things” to give voice to particular sentiments, especially to power and capital” also forms an important theoretical context for the dissenting practice by designers. We have chosen these theories – agency, communities of practice, correspondence and care – to investigate the designer’s role in civic pedagogies of co-making that focus on producing resilience.

4. Design-Led civic pedagogies of co-making in the Global North and South

Both in the Global North and South, there is an emergent field of civic pedagogies of co-making which involve designers in diverse ways and engage participant networks at different scales, from neighbourhood to the city and beyond.

In the Global North, many civic pedagogies of co-making are linked to universities. For example, the Urban Room Live Works, set up by the Architecture School at the University of Sheffield, is managed by architects, university lecturers, students and researchers. In the United States, Architectural design/build pedagogy Rural Studio is connected to Auburn University, and produces specific built outputs working with communities to educate architects as citizens (ruralstudio.org).

Other civic pedagogies of co-making are led by independent design practices. In the UK, Assemble use co-making to design objects with communities (assemblestudio.co.uk) through a designer-led and collaborative practice. Publicworks co-create artworks, architecture and performance as critical civic practice with communities (publicworksgroup.net), namely through their School for Civic Action, a platform for learning and making with multiple organisations and individuals across London. The Centre for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) in New York, is an organisation co-run by designers, educators, students, and communities to make accessible educational tools that communicate policy and planning issues (welcometocup.org). In France, Atelier d’Architecture Autogeree (aaa) utilises neighbourhood co-making as activism to empower the public to take ownership of their local environment (Petrescu Citation2012). In Germany, Raumlabor uses co-making to create experimental learning spaces, such as Floating University, where new relations with nature can be tested (raumlabor.net).

Lastly, some civic pedagogies of co-making practices are school-oriented and work with younger people using design as an educational tool, such as Store projects and Matt and Fiona (both London, UK) who run building activities with young people, in and out of school hours and premises (storeprojects.org; mattandfiona.org). Although limited, these GN examples aim to show that designers’ roles in civic pedagogies of co-making can vary in scale, and in transversality (institutional and non-institutional) to form interrupting processes (Biesta Citation2012) that have social impact.

In the Global South, civic pedagogies of co-making are also increasing, particularly in India. Many are led by young independent design practices. Architecture practice Put Your Hands Together (PYHT) engages people in self and sustainable building methods, working with communities and craftspeople to share and learn techniques and methods, in Nepal and India (information from PYHT April 2021; pyht.org) with private clients and self-funded means. Similarly, Design Jatra combine work with natural materials and traditional methods, and a social enterprise with tribal communities who make small bamboo products (designjatra.org). Organisation Fresh and Local collaborates with neighbourhoods, NGOs and schools to design and build urban green spaces to produce food, working with everyday craft in the city (freshandlocal.org), combining privately funded and donation/volunteer work to run projects; Dharavi Art Room run by artist-researchers, uses photography to engage disadvantaged children across Mumbai in creating zines and exhibitions with affordable resources (artroom.mystrikingly.com), relying on donations to support the work financially; and the Fearless Collective, a group of artists based in Bangalore, works to create space with women and girls by co-painting artworks in public spaces. Co-making projects between institutions and the city environment can also be found: In the city of Pune a project between Vishwakarma Institute of Technology PVP College of Architecture, SUM Net India, Prasanna Desai Architects, the municipality, and the Centre for Environment Education, brought together residents to think about the design of their streets through architectural design workshops (Bari Citation2013). Additionally, a project by researchers with migrant women workers living on the outskirts of Delhi, co-created a feminist sewing group, who use embroidery for political expression (Bathla and Garg Citation2020). Again, these practices share a concern for publicness through interruption (Biesta Citation2012).

These practices involve “non-experts” in co-production; designers in curation, leadership and/or management; aim to increase agency and democracy of citizens; and increase the value of underestimated making processes or materials, to greater or lesser extents, and towards urban equality and care. Artists/researchers/designers are the agents who initiate the co-making projects with marginalised communities or “non-experts”, as a means of building wider agency and sharing power, by creating new civic pedagogical networks. The communities of practice that are created are through the use of design activities, transforming practice. There is also correspondence: the participants create something new bringing their own knowledge and experience to the table (Ingold Citation2013). And finally, they engage in an ethics of care as a spatial concept (Trogal Citation2017a), by empowering the participants through accessible everyday activities, materials, and techniques, as a critique of the predominant contexts; their practice is a critique of architectural and design practice (Tronto Citation2020).

As pedagogies, these practices combine elements that are instructional, conscientising and interrupting to varying degrees as a contestation of normative practice (Biesta Citation2012). However, there is a gap in understanding the particular methods and role of designers in leading these pedagogical processes and in how such processes can conduct to increased resilience; and how similar or different can these roles be across Global South and North, that we discuss through examining our case studies. The two projects that we will compare next also use designers to engage with instruction, conscientisation and interruption. They also include non-experts in co-design, at varying scales, producing artefacts as well as strategies. We want to compare these projects of different scales in different geo-economic locations in more detail in order to identify what particular and universal processes of co-making enable transversal relationalities towards pedagogic urban resilience.

5. Methodology

To understand how co-making can increase urban learning we compare two designer-led civic pedagogies: one is a project with young people in Mumbai, India, entitled Collective Design Pedagogy (CDP) in collaboration with NGO Muktangan School, a class of schoolchildren and their teachers, the local informal settlement neighbourhood Mariamma Nagar and the craftspeople who work there; the other, entitled Eco Nomadic School (ENS), is an informal network and a nomadic structure network across rural, urban and suburban contexts in Europe, involving projects, practices, participants from six countries, nine regions, four cities, two towns and six villages. The two projects were instigated by designers and developed incrementally over 6 and 10 years respectively; data collected during this time ranges from visual (drawings, photographs and videos), audio recordings, interviews with participants, expert and non-expert site surveys, workshop plans and meeting notes, whatsapp messages, and designed and built interventions at a 1:1 scale in situ. In terms of research and design approaches, both projects use co-making as a method, co-design as a methodology, and co-production as a strategy at multiple scales – all processes of sharing power and responsibility in the formulation of the project, towards shared responsibility and ownership. This paper focuses retrospectively on identifying the roles of the designers in relation to the civic co-making activities and the potential for pedagogical resilience.

6. Case study 1. Co-making and collective design pedagogy for resilience with Muktangan school, Mumbai

In 2011, one of the authors began working with a group of 28 children and staff from NGO Muktangan Love Grove School in Mumbai, planning and running a series of workshops that would span six years (with the same group), as a participatory action research project to explore how design could help children develop the right to (and responsibility for) the city (Antaki Citation2021, Antaki Citation2021). The workshops were designed as pedagogical experiments, held during school hours and according to appropriate ethics codes, as part of the school curriculum. During these sessions, the children themselves became designers, and the designer, a facilitator. Love Grove School caters largely for inhabitants from neighbouring informal settlement Mariamma Nagar, a small settlement home to a large number of craftspeople who work with textiles (e.g. tailors, embroiderers, bag makers). During workshops, the children were encouraged to use typical architectural activities such as observing, mapping, researching, ideating, assessing, commissioning and presenting to their neighbourhood community; they created architectural objects such as sketches, models, drawings, and prototypes, working with materials and processes found nearby. The designer-facilitator used a critical pedagogical methodology (of action-reflection) to study the workshops, make comments and recommendations and process visual data. The aim of the project was to produce a toolkit usable by other schools, neighbourhoods and networks.

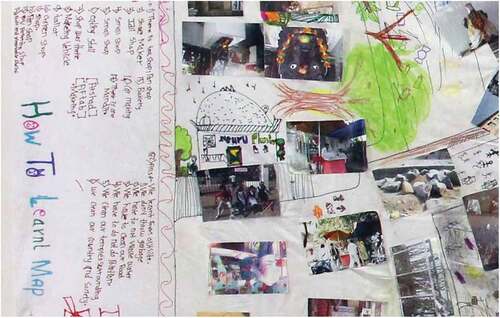

The designer’s role was to design the pedagogy; to plan, organise and facilitate the workshops, which were developed to complement school curriculum. This required exploration and preparation of the participants and collaboration with school staff, building a knowledge base of local everyday material resources and crafts to create a pool of activities that could help define the project outputs. Many of the pedagogic activities used co-making as a co-design method. In 2014, during school work experience sessions, the children were invited to make a map of their neighbourhood during a collective mapping project; in 5 facilitated groups, they walked around the neighbourhood, documenting activities, spaces and inhabitants, using cameras to take photographs and sketch pads to make maps of the area. Upon returning to the classroom, on a large pre-prepared base (on a bedsheet), they collaged printed photographs, drew, and annotated their local map (), facilitated by the designer and class teachers.

Figure 1. Detail from the neighbourhood map made by pupils from Muktangan school/Mumbai during collective design workshops 2014.

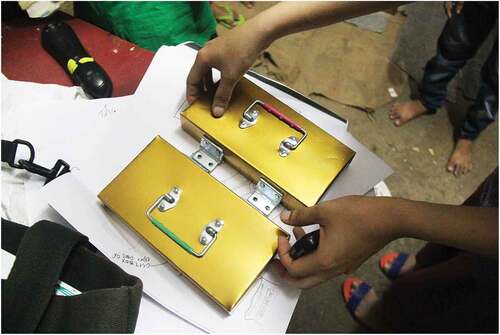

Subsequently in 2015–2016, the same children were invited to design interventions for their settlement (during art and craft sessions), this time with a group of 5 designer-facilitators. The children were asked what they would like to change in their neighbourhood, and selected five design themes: Mosquitoes, fighting and bad language, open/broken gutters, recycling and waste management and the need for more trees in the settlement. They conducted a craft audit, identifying a palette of accessible materials and makers with whom to work, including bag makers, tailors, hand and machine embroiderers, and tin box makers. Using design techniques, they designed responses to the issues they had raised. For the mosquito issue, they designed embroidered mosquito net door and window frames; for fighting and bad language, a debating table and a tin fine box; a movable planter and an embroidered cloth shopping bag to raise awareness of the need for green space; new segregated tin waste bins for recycling; and a gutter cover made from tin box lids (). The designers and the children worked with local makers to fabricate prototypes, using their drawings as tools for conversation (). The final prototypes were fabricated, facilitated by the designers in the makers’ workshops while the children were at school (). Finally, the children presented their designed objects to the neighbourhood community, parents, craftspeople and school through a series of public presentations that shared the work by the new community of practice, widening the sharing of knowledge into the settlement.

Figure 2. Tin box lids at a boxmaker’s workshop are repurposed to make the pupil’s gutter cover prototype, Mumbai 2016.

7. Case study 2. Co-making and mutual learning for resilience in different rural, urban and suburban contexts in Europe, with eco nomadic school

Eco Nomadic school is an informal network and a nomadic structure involving projects, practices, participants (researchers, artists, architects, farmers, students and ordinary people) from six countries, nine regions, four cities, two towns and six villages in Europe. The project has been initiated by atelier d’architecture autogerée- aaa (France) in 2011 with EU funding and involved the artist collective myvillages (Netherlands-Germany), the University of Sheffield (UK), the design practice Brave New Alps (Italy), and the civic organisation FCDL Brezoi (Romania) as long-term partners. The people travelled, met, discussed, did things together in different configurations for over ten years. The main goal of the school was to allow a transversal and translocal exchange of actionable knowledge for a more socially just ecological transition and increased resilience across institutions and organisations in different local contexts in Europe through a “light” infrastructure that can be sustained in time with everyone’s contribution. The school was a long-term co-production process which involved many forms of mutual learning and two-ways exchange between very diverse persons and groups involved in diverse practices of ecological co-making in their own contexts: carpentry, farming, food processing, etc. The network of participants was very large and diverse: in terms of people – peasants, researchers, students, city dwellers, asylum seekers, etc … ; but also in terms of non-humans: animals and plants, local materials, tools and skills, policies, etc. ()

Figure 5. Wood building workshop in Brezoi/Romania, involving local craftmen and residents of Brezoi, specialists in eco-construction from Paris and students from Bucarest/Romania and Sheffield/UK, Economadic School 2014.

Figure 6. Wood building workshop in Colombes/France, involving craftspeople from Brezoi/Romania, residents of colombes, and students from Paris and sheffield, economadic school 2014.

In the Eco Nomadic School, teachers and learners were changing roles and the participant configuration evolved continually. Someone who was a teacher in the small town of Brezoi, Romania (running a workshop on fermentation) at another moment would be a learner in the suburban town of Colombes, France (learning about household economy marketing), and so on. () The classes meant to answer very precise needs for learning in different locations were different in object and goals and included very diverse (co-)making processes: from making food, making buildings, objects and tools, making services, etc … all involving a group of teacher-learners. The designer role, played by aaa and their artist and activist partners, was to design situations of mutual learning as workshops, events and transversal encounters, across levels, cultures, ages, and contexts within the actor network. They also facilitated the pedagogies of co-making that were proposed by the participants and enabled the knowledge base of local non-human material resources and crafts to be shared with others. Co-making workshops (on topics such food fermentation and conservation, wood building, local marketing and communication, etc) were co-designed with the local organisers, and were staged and documented by the designers. Amongst the outputs, there was also a collectively managed website and a book manual.

Figure 7. Community economy workshop in Colombes/France, involving specialists in economy and branding from UK, local residents from Colombes/France, Brezoi/Romania and Rotterdam/Netherlands, economadic school 2014.

This undertaking was called “Learn to Act” as a proclamation that knowledge can become shared, collective and applied. Knowledge becomes a vehicle for how to act and how to support each other in the ambitious undertaking of transforming the world resiliently, there where we are. The initial collective motivation gained a political dimension based on the conviction that pedagogy and education do not exist solely in schools and in institutions, but also within the civic realm: in activist initiatives, through political struggles, through economic undertakings, through making practices, and, ultimately, in everyday life.

8. Discussion

To compare the two case studies, we have used a table to analyse the respective designer roles in relation to the four theoretical concepts set out above: agency (Giddens Citation1984), communities of practice (Lave and Wenger Citation1991); correspondence (Ingold Citation2013); and as practices of care (Trogal Citation2017a; Tronto Citation2020).

(See ).

8.1. Agency

In both projects, it was the role of the designer to initiate the project, choose the participants, co-design the pedagogy and workshops with partners, build and nurture the network, document and communicate the process – both on and offline. It was also their role to raise funds. The Collective Design Pedagogy (CDP) involved six partners: Muktangan school, Mariamma Nagar neighbourhood community, craftspeople, children, and designer-facilitators. Muktangan School staff co-designed the workshops during planning meetings, as a jointly owned, shared work in progress, allowing the designed outputs to be determined by the participants. The Eco Nomadic School (ENS) invited initial participants: 6 organisations in different locations in Europe including Universities, cultural institutions, civic organisations, a cooperative business and rural art organisation. The designer identified the products that were made collectively in different contexts to become the points of connection; e.g. the schnapps, the fermentation techniques, the sauerkraut etc … In the CDP, the designer-facilitator incrementally raised funds from pots available to researchers at the associated university and other doctoral funds, and the ENS applied for, and successfully received, European funding; both matched applications according to interest and tailored projects to calls.

8.2. Communities of practice

Encouraging transversality, the designer as social maker supports existing communities of practice and creates new ones. The ENS was based on Wenger’s notion of “communities of practice” (Wenger Citation1998), working as an informal learning network that developed through informal groupings drawn together by common challenges, opportunities or passions. Knowledge communities functioned by bringing groups together to share previous experiences from different contexts, thus leading to much more effective problem solving. A good example is the community of fermentation practices that grew within the Eco Nomadic School, with people from Brezoi, Amsterdam, Colombes and Hoefen all sharing their own version of the simple schnapps. Likewise, a community of gardeners, a community of wood builders, a community of husbandry and household economies has developed within the school.

In the CDP, the designer, an outsider, adapted to existing communities of practice such as the class, education NGO, craft and settlement community (including adaptations such as learning language, dressing a certain way, behaviour in the settlement etc). Work aimed to support local resources and local economies: an activity to map existing communities of practices was carried out, and shared as a part of a set of taught design skills.

Both projects also deal with “situated learning processes”. In the CDP, for all participants pedagogy and learning is a form of jugaad across the neighbourhood; whereas in the Eco Nomadic School transversal peer learning happens across EU communities.

In both projects design methods were shared or organised to be shared by the designers to enable the production of artefacts. At Muktangan School, co-design and co-making methods enabled the schoolchildren and the craftspeople to work together towards the prototypes. At the ENS the co-making workshop with designers from BraveNewAlps and asylum seekers in Roveretto enabled development of spatial elements and communication tools for the research-and-resource centre. ()

Figure 8. Self-Building workshop in Rovereto/Italy, involving local designers and activists, residents and asylum seekers and students from Sheffield/UK Economadic School, 2016.

In both projects, relationships with universities lead to long-term engagement, thanks to the need for meaningful research findings, in answer to research questions. The CDP was developed with the support of UCL School of Architecture and the Development Planning Unit and associated funders; whereas the Eco Nomadic School was supported by the School of Architecture at the University of Sheffield.

8.3. Correspondence

In both projects, the designers facilitated the co-making workshops. They used design tactics and techniques “to steer social processes to interpret the co-made artefacts as products of material and social negotiations” (Popplow Citation2016). As correspondent, the designer creates co-making opportunities, to allow for transversal learning through shared decision-making; her behaviour needs to adapt reflexively as necessary to assimilate or instigate critique. At Muktangan, the designer facilitated conversations between craftspeople and schoolchildren for fabrication of designs using drawings; between the school staff and facilitators, communicating the workshop plans, timetable, logistics and resources; between the schoolchildren and their parents with ethics approvals and consent forms; between the schoolchildren and the neighbourhood by curation and provision of the tools with which the children could correspond with the site. The Eco Nomadic School is a purposely designed “relational” project which connects communities across different geographies. This form of school, and taking part in it, is a political act, which promotes civic responsibility on a local and trans-local level. Learning as part of the school is also a form of empowerment for existing local groups to start (and continue) diverse practices, where social, ecological and economical concerns meet and merge.

In civic pedagogies of co-making, “knots” can be understood as unlikely encounters between parties which generate transformations (Ingold Citation2013). In the CDP and the ENS, the designer mediates encounters between actors, with a view to creating “knot” potential. Knots are key decision moments, intersecting traditions and local knowledges, enabling the “meshwork” of social life (Ingold Citation2013). In both projects, the designer facilitated the creation of “knots”. In the CDP, the children’s design for creating a new gutter cover for the neighbourhood made with a local resource of tin box lids, is a knot: the tin makers (teachers) and the children (architects) created new resilient knowledge by combining their ideas and skills. This moment brings together actors to define a subsequent new route as a resourceful transformational response to the current situation. In the ENS, a knotting would take place between heterogenous participants from different EU locations. They can gather and exchange knowledge around the same nonhuman actor they all know, such as the sauerkraut, that acts as a mediator. They can also change roles: in one context participants are “teachers” or experts, yet in another they participate as students, and roles are reversed. In both cases the designers orient/create the possibility of this transformation.

Designers are also correspondents creating knots and knowledge through research. By analysing data collected during civic pedagogies of co-making, new knowledge and understandings are being created, underpinning transversal relationships between communities and universities.

8.4. Care

In both projects, the designer acts as a caretaker, caring for spatialities and environments as a form of spatial production and sharing the power to do so. Towards this, both projects’ understand “resilience” as a resourcefulness (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2013); further, they both facilitate the identification of necessary improvements in household, community and ecological health, social and psychological wellbeing, civic involvement and participatory democracy (Petrescu and Petcou Citation2020). The project teams identify local resources and learn to work with them, making them visible and valorising the co-makers/craftspeople by defining them as teachers. Muktangan School work with local settlement craftspeople (tin box-makers, embroiderers, tailors, carpenters) to create site situated interventions that respond to environmental and wellbeing difficulties; and Eco Nomadic School works with community economies such as pickling, preserving, composting, sheep-shearing, wool-processing, mushroom picking etc … across Europe.

For both projects, everyday craft is a key part of civic pedagogy towards building community resilience – or a problem-finding/problem-solving activity (Sennett Citation2008). The projects enabled opening up of situated practices of making to different actors and international peers. Both projects strive for outputs that improve everyday life and increase (community) agency, albeit at different scales – CDP at a neighbourhood scale and ENS both at local and trans-local scales.

In instigating the project with “non-experts”, the caretakers have particular interests in the reciprocal pedagogical role co-making can play in the production and critique of the environment, whether in Mumbai or in the different European locations involved in ENS. In both projects, participants are “learning to act” (Böhm, James, and Petrescu Citation2017), with the aim of increasing resilience through everyday practice both by carefully sharing agency and tools for change. In one, there are children and young people, in the other there are adults of different ages. Further, both projects produce resources by which others may also take part in these activities: the CDP through a re-usable activity toolkit for schools and students, downloadable online; and ENS through the website and the co-designed publication “Learn to Act”.

Although this paper is arguing for similarities, there are also many differences in the civic pedagogies of co-making discussed. In India, everyday craft is accessible – commissioning a tailor, a weaver, a carpenter; having shoes, suitcases or appliances repaired, are part of daily life. Neighbourhoods such as informal settlements, predominantly found in the Global South, are environments of porosity in which informal making thrives. The making practices engaged by the Eco Nomadic School, were home economies of making, rather than commissions to makers. We can learn from the Collective Design Pedagogy that informality or jugaad can enable transversal methodologies, a way of overturning difficulties to build the network of actors necessary to create the pedagogy. In the South, the designer took on more than one role, to create a community of practice that did not previously exist (between craftspeople, children, students), underlining the importance of the role of designer as agent. In the North, the designer had a more equal role in the network of actors. There are temporal differences too. In the ENS the projects were developed between adults who were considered “designers” in the present. In the CDP, the children are becoming designers facilitated by adults – it is a practice that is looking to the future through the manifestation of emerging citizenship (Orton-Johnson Citation2014).

Differences also lie in the legitimacy of the work via institutions. In the South, the role of the institution was instrumental in legitimising the practice, led by an outsider; in the North, the institution was an equal partner - one of many participants with equal agency. We can learn that from the ENS, horizontal, equal practices can be implemented sustainably, and from the CDP, how unequal partnerships may be more unsustainable. Further, the ENS took advantage of cyclical European funding, which made the network sustainable in time, with multiple active and responsible stakeholders enabling many projects to be individually run and initiated as part of a whole. The designer role is not fixed and central, being taken turn by turn by actors within the network who were designing “knots” - encounters and actions- over a 10-year period. The CDP was incrementally organised by one designer, making it difficult to run without the usual leader, creating a need for a toolkit to allow for potential self-organisation. Consequently, multiple and equal stakeholders are necessary to enable sustainable civic pedagogies of co-making.

9. Conclusion

This paper shows how civic pedagogies of co-making can bring together diverse participants (new, harder to reach, non-experts) to learn something new through making, and increase resilience through resourcefulness. These pedagogies work at multiple scales from the home to neighbourhood, the city and further on, from individual to group. They allow for translocal and transversal learning, moving from micro to macro through the scales and identities of various communities of practice, creating knowledge through knots and made artefacts, with the potential to cross boundaries, and be repeated with caring and locally relevant results.

The paper argues that through civic pedagogies of co-making designers can take new roles: they can be agents, social makers, correspondents and caretakers. As agents, designers identify and create the network, helping drive the processes of co-making by curating and supporting activities. As social makers, designers can encourage situated learning within and between existing and new communities of practice. As correspondents, they manage and mediate relationships between participants while instigating opportunities for correspondence and knot (knowledge) creation; and as caretakers, they help create pedagogical situations towards caring for spatialities by sharing of power. Together, these roles create potential for environmental and social resilience, thanks to the myriad opportunities for resourcefulness and interdependence (Trogal Citation2017b).

The comparison of case studies situated in the Global South and North has allowed us to see the universal potential of civic pedagogies of co-making, considering also their social and environmental differences. This paper puts forward a number of new contributions to knowledge. First, the new necessary roles that designers play in leading civic pedagogies of co-making. Second, a new understanding of co-making as a form of civic resilience that can be social, economic, spatial and political; creating communities of practice, of varying age-groups, backgrounds, ethnicities. Third, that “learning to act” is itself a (civic) pedagogy, with learning as a position of inquiry and curiosity that provides a framework for and orients the active process. Learning is actionable, deriving from everyday life and informing actions of collective resilience in the future. It is for an engaged resilient citizenship. And lastly, the structure of a civic pedagogy needs to allow for forms of jugaad, so that it can constantly reflect its current situation/context, enabling imaginative contestations and negotiations that are environmentally and socially resilient.

There is potential for these findings to influence further practice: in the way that we describe the new roles for designers, to use design skills in the balanced proposal of creating civic pedagogies of co-making involving non-experts; through the emphasis on the importance of the formation of ‘knots ‘of “correspondence” (Ingold Citation2013) necessary to form civic resilience; and to highlight that the use of design in civic pedagogies of co-making can have a particular ability to build commoning relationalities, and therefore, resilience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Antaki, N. 2021. “A Learning Architecture: Developing a Collective Design Pedagogy in Mumbai with Muktangan School Children and the Mariamma Nagar Community.” Research for All 5 (1): 101–117. doi:10.14324/RFA.05.1.09.

- Baibarac, C., and D. Petrescu. 2019. “Co-Design and Urban Resilience: Visioning Tools for Commoning Resilience Practices.” CoDesign 15 (2): 91–109. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1399145.

- Bari, P. 2013. ”For the People by the People’, Pune, Aundh.” Jagran City Plus 5 (47): 16–22, November.

- Bathla, N., and S. Garg. 2020. “Radical Housing and Socially-Engaged Art – Reflections from a Tenement Town in Delhi’s Extensive Urbanisation.” Radical Housing Journal 2 (2): 35–54. doi:10.54825/HFEH7946.

- Bell, D. M., and K. Pahl. 2017. “Co-Production: Towards a Utopian Approach.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology. doi:10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581.

- Biesta, G. 2012. “Becoming Public: Public Pedagogy, Citizenship and the Public Sphere.” Social & Cultural Geography 13 (7): 683–697.

- Birch, J., R. Parnell, M. Patsarika, and M. Šorn. 2017. “Creativity, Play and Transgression: Children Transforming Spatial Design.” CoDesign 13 (4): 245–260. doi:10.1080/15710882.2016.1169300.

- Boano, C., and G. Talocci. 2014. “Fences and Profanations: Questioning the Sacredness of Urban Design.” Journal of Urban Design 19 (5): 700–721. doi:10.1080/13574809.2014.943701.

- Böhm, K., T. James, and D. Petrescu. 2017. Learn to Act: Introducing the Economadic School. Paris: Peprav-AAA.

- Carli Beatrice, D. 2016. “Micro-Resilience and Justice: Co-Producing Narratives of Change.” Building Research and Information 44 (7): 775–788. doi:10.1080/09613218.2016.1213523.

- Chanchra, D. 2016. Interviewed In: Looking Sideways: A Podcast About Making Things. 2 (1), February 21. https:// lookingsideways.net/s02e01/.

- Fitz, A., and E. Krasny. 2019. Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet. Cambridge, MA: Architekturzentrum Wien; MIT Press.

- Frediani, A., C. Cocina, and M. Acuto. 2019. Translating Knowledge for Urban Equality: Alternative Geographies for Encounters Between Planning Research and Practice. London: KNOW, Development Planning Unit, University College London.

- Freire, P. 1970. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Gandhi, M. 1947. Basic Education. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Giroux, H. A. 2004. ”Critical Pedagogy and the Postmodern/modern Divide: Towards a Pedagogy of Democratization.” Teacher Education Quarterly 31 (1): 31–47.

- Hofverberg, H., and D. O. Kronlid. 2018. “Human-Material Relationships in Environmental and Sustainability Education – an Empirical Study of a School Embroidery Project.” Environmental Education Research 24 (7): 955–968. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1358805.

- Hooks, B. 2003. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. Routledge.

- Hopkins, R. 2009. “Resilience Thinking.” Resurgence 257: 12–15.

- Illich, I. 1971. De-Schooling Society. New York: Harper & Row.

- Ingold, T. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2017. “On Human Correspondence.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12541.

- Jones, B., P. Peter, Doina, and J. Till. 2005. Architecture and Participation. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780203022863.

- Julier, G., and L. Kimbell. 2019. ”Keeping the System Going: Social Design and the Reproduction of Inequalities in Neoliberal Times.” DesignIssues, Vol. 35, 4. MIT Press. doi:10.1162/desi_a_00560.

- Krasny, E. 2012. The Right to Green: Hands-On Urbanism 1850-2012. Hong Kong: MCCM Creations.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Levick-Parkin, M. 2018. ‘How Women Make - exploring female making practice through Design Anthropology’. EdD thesis, University of Sheffield.

- Liu, P., and L. Lan. 2021. “Museum as Multisensorial Site: Story Co-Making and the Affective Interrelationship Between Museum Visitors, Heritage Space, and Digital Storytelling.” Museum Management and Curatorship 36 (4): 403–426. doi:10.1080/09647775.2021.1948905.

- MacKinnon, D., and K. D. Derickson. 2013. “From Resilience to Resourcefulness: A Critique of Resilience Policy and Activism.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (2): 253–270. doi:10.1177/0309132512454775.

- Manzini, E., and F. Rizzo. 2011. “Small Projects/large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process.” CoDesign 7 (3–4): 199–215. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.630472.

- McFarlane, C. 2012. Learning the City: Knowledge and Translocal Assemblage. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- McQuilten, G., and A. Spiers. 2020. “Art is Different’: Material Practice, Learning and Co-Making at the Social Studio.” Journal of Arts & Communities, Intellect, Intellect 10 (1–2): 19–33.

- Orton-Johnson, K. 2014. “DIY Citizenship, Critical Making and Community.” In DIY Citizenship, edited by M. Ratto and M. Boler, 141–156. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Oxford Dictionary of English. 2018. Oxford University Press.

- Parnell, R., V. Cave, and J. Torrington. 2008. “School Design: Opportunities Through Collaboration.” CoDesign 4: 211–224. doi:10.1080/15710880802524904.

- Petcou, C., and D. Petrescu. 2015. “R-URBAN or How to Co-Produce a Resilient City.” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 15 (1): 249–262.

- Petrescu, D. 2005. “Losing Control, Keeping Desire.” In Architecture and Participation, edited by P. Blundell-Jones, J. Till, and D. Petrescu, 43–64. Routledge.

- Petrescu, D. 2012. “Relationscapes: Mapping Agencies of Relational Practice in Architecture.” City Culture and Society, Elsevier, Elsevier 3 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2012.06.011.

- Petrescu, D., and C. Petcou. 2020. “Resilience Value in the Face of Climate Change.” Architectural Design 90 (4): 30–37. doi:10.1002/ad.2587.

- Petrescu, D., C. Petcou, and C. Baibarac. 2016. “Co-Producing Commons-Based Resilience: Lessons from R-Urban.” Building Research & Information 44 (7): 729. doi:10.1080/09613218.2016.1214891.

- Popplow, L. 2016. “Co.Making – Design Participation in Transformation? An Experimental-Programmatic Research” In NERD - New Experimental Research in Design, edited by M. Erlhoff, W. Jonas, and W. de Gruyter. GmbH.

- Radjou, N., J. Prabhu, and S. Ahuja. 2012. Jugaad Innovation: Think Frugal, Be Flexible. San Francisco, California: Generate Breakthrough Growth.

- Rice, L. 2018. “Nonhumans in Participatory Design.” CoDesign 14 (3): 238–257. doi:10.1080/15710882.2017.1316409.

- Sadka, O., and O. Zuckerman 2017. ‘From Parents to Mentors: Parent-Child Interaction in Co-Making Activities’, Conference on Interaction Design and Children 2017 Stanford CA.

- Sanders, E. B. N., T. Binder, and E. Brandt. 2013. “Tools and Techniques: Ways to Engage Telling, Making and Enacting.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by J. Simonsen and T. Robertson, 145–181. New York and London: Routledge.

- Schneider T., and Till J. 2009. ”‘Agency in Architecture: Reframing Criticality in Theory and Practice.” Footprint: 97–111. Spring 2009.

- Sennett, R. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven CT and London: Yale University Press.

- Tagore, R. 1936. ”Visva-Bharati Bulletin”. 21.

- Torrey, T., R. W. Maloy, and S. Edwards. 2018. “‘Learning Through Making: Emerging and Expanding Designs for College Classes.” TechTrends 62 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1007/s11528-017-0214-0.

- Trogal, K. 2017a. Caring: Making Commons, Making Connections. Oxford: The Social Re Production of Architecture, edited by. K. Trogal and D. Petrescu. Routledge.

- Trogal, K. 2017b. “Resilience as Interdependence: Learning from the Care Ethics of Subsistence Practices” In Architecture and Resilience, edited by K. Trogal, I. Bauman, R. Lawrence, and D. Petrescu, 190–203. Oxford: Routledge.

- Trogal, K., A Wakeford. Forthcoming. Designing with Care: Theorising Care for Contextual and Relational Design Practices. Unpublished.

- Tronto, J. C. 2020. “Caring Architecture.” In Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet, edited by A. Fitz and E. Krasny. Vienna: Architekturzentrum Wien.

- Tronto, J. C., and B. Fisher. 1990. “Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring.” In Circles of Care, edited by E. Abel and M. Nelson, 36–54. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Von Busch, O. 2013. “Collaborative Craft Capabilities: The Bodyhood of Shared Skills.” The Journal of Modern Craft 6 (2): 135–146. doi:10.2752/174967813X13703633980731.

- Ward, C., and A. Fyson. 1973. Streetwork: The Exploding School. Oxford: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.live-works.orgwelcometocup.orgassemblestudio.co.ukpublicworksgroup.netpyht. https://raumlabor.net/floating-university-berlin-an-offshore-campus-for-cities-in-transformation/rhyzom.euurbantatics.org

- Wenger, E. 2010. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept” In Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice, edited by C. Blackmore, 179–198. London: Springer.