ABSTRACT

Co-designing with Indigenous people premises an obligation to participation as a fundamentally ontological and transformational place-based way of working, often challenging the dominant notions of what ‘participation’ and ‘design’ means in practice. This paper considers how non-Indigenous design researchers engage and transform through being in dialogue together on Country. Here, the Western Arrarnta concepts of ‘purta ngkarrama’, of people talking together in dialogue, and ‘purta kaltjerrama’, of people learning together, are explored as ways to realise pluriversal and decolonial approaches to co-design. Drawing on personal reflexive learnings from a four-year co-design education programme in the Aboriginal community of Ntaria, in the Central Desert of Australia, these dialogues emerged through exploring Western Arrarnta's ways of learning, doing, being, and designing. Becoming a participant ‘in’ dialogue, ‘on’ Country, requires us to rethink ways of participating within design research. Premising talking and learning together in dialogue presents an opportunity for co-design researchers to be personally engaged, embodied, and transformed through research – and where more accounts of listening and learning together can emerge.

1. Co-designing on country

Building on discourses within co-design around Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous researchers collaborating together and the challenges with dominant notions of what ‘participation’, ‘design’ and ‘knowledge’ means (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; Schultz Citation2018; Winschiers-Theophilus, Bidwell, and Blake Citation2012), this paper considers how non-Indigenous design researchers engage, negotiate, and transform through being in dialogue on Country. This paper draws on learnings from a four-year co-design education programme in the Aboriginal community of Ntaria, in the Central Desert of Australia. This programme focused on teaching and learning digital drawing and communication design at Ntaria School to codesign a local and culturally led design pedagogy that was meaningful and valuable to the students and community (St John Citation2020). Exploring how Western Arrarnta young adults value and make meaning from digital drawing tools involved first understanding, and then embedding Western Arrarnta's ways of learning, doing, being, and designing. Here, the Western Arrarnta concepts of ‘purta ngkarrama’, of people talking together in dialogue, and ‘purta kaltjerrama’, of people learning together, are explored as ways to realise pluriversal approaches to participation. In doing so, co-design learns from the rhythms and relationalities of Country and community as a transformational co-ontology – and becomes a relational dialogic practice where knowledge, place, and ways of being and learning entwine.

Co-designing with Indigenous people premises an obligation to participation as a fundamentally ontological and transformational place-based practice (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; St John Citation2022b; St John and Akama Citation2022). By extension, practices of decolonising co-design require respecting Indigenous worldviews and onto-epistemes as the foundation for collaborative work (see Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; Rodil et al. Citation2019; Schultz Citation2018). This can often challenge universal norms of co-design practice and invite methodological tensions for design researchers emplaced within laws, obligations, and relationships on Country (St John and Akama Citation2022). The emphasise of the term ‘Country’ respects its usage from Aboriginal people, who like Elders Uncle Charles Moran, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Professor Norman Sheehan describe how ‘as a conception Country exists outside as a living vital place that we inhabit and through learning culture and respect … it also exists inside as a model for being human in a proper way’ (Moran, Harrington, and Sheehan Citation2018, 75).

Co-creating a design education programme in Western Arrarnta Country required a deep commitment to listening to – and learning from – Western Arrarnta’s students and community, to collaboratively develop learning experiences and outcomes. In unpacking my reflexive accounts of listening and learning below, revealed is a personal process of ‘undoing’ my Euro-centric conceptions of design, education, and research participation to adapt to the rhythms of Western Arrarnta life. For the Ntaria students, whose cultures and knowledge are not represented within design histories, discourses, or practices, their digital drawing outcomes are particularly powerful, as they assert their own design languages and the production of knowledge through new modes of digital creative practices.

Learning and becoming ‘in dialogue together’ was about framing co-designing as an ongoing reciprocal conversation and making space for reflection, continuously asking: ‘Nthaakinha nurna purta urrkaapuma, relha English-akarta relha Western Arrarnta-lela ngkarramanga?’ Or how can we work together, Westerners dialoguing with the Western Arrarnta people? As a settler-colonial woman, I also understood that I too was a committed participant and learner in the process of ‘doing’ the work (St John and Edwards-Vandenhoek Citation2022). With this dialogue also acknowledging the technological abilities, visual literacies, and teaching expertise I brought to this relational knowledge space. In sharing personal reflexive accounts of co-design, this paper aims to go some way to address the gaps identified by design researchers that decolonial design discourse lacks nuanced and empirical examples and has yet to fundamentally affect participatory and co-design practices (Smith et al. Citation2020).

While personal accounts of co-design research, and the process of becoming relational are typically removed from conventional academic notions of ‘rigour’ or ‘validity’, they also point to broader challenges and assumptions that case studies provide, or researchers produce ‘frameworks’ or ‘techniques’ that be applied elsewhere, by others (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; St John Citation2022b). Argued here, is how researchers can explore dimensions that are not replicable but focus on becoming a participant ‘in’ dialogue, ‘on’ Country, to rethink ways of participating, and re-consider what can be legitimated as ‘knowledge’ emerging from empirical studies where the researcher is personally embodied within collaborations and dialogue, such as the case discussed here. The relevance of these questions for plural worlds highlights how practices of co-design necessarily involve the co-existence of multiple modes of beings and ways of knowing. These are exciting opportunities for co-design – and where more accounts of listening and learning together can emerge.

2. Considerations on participation

Dominant Eurocentric participatory design methods are often seen as incompatible with other cultural modes, knowledges, and social habits (see Nieusma Citation2004; Winschiers-Theophilus, Bidwell, and Blake Citation2012). Co-design scholars increasingly articulate how these methodological and theoretical gaps have meant the discipline has yet to meaningfully recognise cultural situatedness and engagement with the underlying ontological entanglements of people’s pasts and presents (Kambunga et al. Citation2023; Smith et al. Citation2020). While cultures and communities conceptualise ‘participation’ in many distinct and localised ways, how pluriversal design is situated and shifting the discipline has yet to be unpacked. While many individual accounts, which explore and expand concepts of participation within codesign continue to enhance the discipline (see, for example, Till et al. Citation2022; Winschiers-Theophilus, Zaman, and Stanley Citation2019), there has yet to emerge a collective discourse, in bringing together these local accounts into a ‘multiplicity’, and in turn linking or drawing parallels towards the plurality of the discipline. Co-designing with Indigenous peoples required an approach that privileges local knowledges, cultures, and ways of relating – troubling many approaches which pre-define how participation is enacted, analysed, and reflected on within research.

Many non-Indigenous co-designers have reflected on their own experiences of participation with Indigenous participants. Reitsma et al. highlight how trying to fit Indigenous knowledges into pre-defined project outcomes creates a lack of trust, and environments where communities ‘participate’ according to the expectations of the design researcher (2014). Winschiers-Theophilus et al. (Citation2010) refer to the concept of ‘being participated’, where researchers are not pre-defining, leading, or deciding in isolation from the community, but are embedded and engaged within the collaborative process. Winnie Chow argues how the Western concepts of ‘participation’ often conflict with Indigenous circular ways of knowing and codes of conduct (Citation2007). Chow enters herself into the research as a hybrid attempting to balance and attend to the needs of each complex world, utilising a ‘reflection-in-action’ framework which embeds practical projects and experiences with Indigenous communities within an ongoing theory of action. As the process of establishing participation is an emergent process that is negotiated in situ, reflecting-in-action can lead researchers to examine their own understandings, make conscious of their underlying assumptions, and be open to and ready for personal encounters, uncertainty, transformation, or new ways of doing things. Reitsma (Citation2021) suggests such reflection-in-action can also support ontological transformations of design researchers, and facilitate internal processes of reflection, understanding, and critically looking.

The ethics and politics of relating and collaborating with Indigenous people overlap in significant ways within decolonial and pluriversal design, in calling for multi-centricity and reflexivity (Dei Citation2014). Many decolonial design discourses engage the notion of the pluriverse to question the concept of universality at the heart of Western epistemology. Pluriversal design offers a counternarrative – that there is no one accepted way to design, learn, teach, know, or be. This relationality welcomes different onto-epistemes to come together to create new ways of doing and becoming through design, while modelling a way for researchers to articulate and reflect on being emplaced in the enactment of co-design practice (St John and Akama Citation2022). These standpoints also accept personal narrative as a valid form of data and acknowledge the collaborative process of engaging as an outcome in itself (Taboada et al. Citation2020). This paper seeks to build on the work of those conceptualising co-design differently, as an ontologically relational and transformational practice, grounded in place and a respect for Indigenous laws and knowledges (see Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019; Rodil et al. Citation2019; Schultz Citation2018). It is therefore important that co-design processes are articulated from local contexts, and personal processes of building relationships with participants further considered, as there is much to learn from entering into dialogue with Indigenous people, community, culture, and place.

3. Co-design in dialogue

Grounding Indigenous knowledge protocols within co-design leads to a deeper consideration of what a decolonial or pluriversal approach to participation might entail and how it might be enacted. Here, I draw on notions of dialogue as a viable relational and respectful approach and look to the literature to explore how it is conceptualised and utilised within codesign practice. Drawing on Bohm’s conceptualisations (2007), dialogue involves a mutual non-judgemental approach by all participants and does not aim to convince others of the rightness of one’s opinion or to merge individual pre-factored ideas, but rather making something in common, or creating something new together. Here, dialogue is not about negotiation, conviction, or persuasion. It celebrates difference and is only possible if people are able freely to listen to each other, without prejudice, and without trying to in fluence each other (Bohm and Weinberg Citation2004). Bohm differentiates dialogue from discussion, which he argues is where people are batting the ideas back and forth and the object of the game is to win or to get points for yourself. Rather, dialogue enables something more of a common participation.

Adopting Bohm’s conceptualisation within codesign practice, Jones, Christakis, and Flanagan (Citation2007) argue that dialogue is a crucial element in participatory design. Sejer, Halskov, and Leong (Citation2012) further that a core task for designers is to facilitate and orchestrate this dialogue. Yet, discussions of dialogue within codesign practice are largely focused between users and the design team (Dankl, Akoglu, and Bro Egelund Citation2023), or as a more continuous mode of communication between designers and researchers (Noronha and Niinimäki Citation2017). Luceroa, Vaajakallio, and Dalsgaard (Citation2012) propose a dialogue-labs method, which provides a structured way of generating ideas through a sequence of co-design activities and the interplay between process, space, and materials. Yet framing dialogue as something that can be carefully crafted, orchestrated, or controlled in a ‘two-hour idea generation’ lab conflicts with Bohm’s notions of dialogue which has no leader, no agenda, and no purpose. Seeing dialogue as an emergent space raises notions of how co-designers can sit within and plan for this uncertainty, give attention to the whole process, cede power and control, and be open to unforeseen encounters. Moreover, how might local Indigenous knowledge approaches differ to how dialogues are framed and understood in Euro-centric participatory and co-design research.

Engaging in dialogue is one of the many ways that researchers are engaging in collaborative research and design activities relating to decoloniality and pluriversality. Sensitivities to local epistemologies and situated collaborative explorations can also be seen through conceptions of ‘correspondence’ through a continued engagement and commitment to particular people and lifeworlds (Gunn, Otto, and Smith Citation2013). Such sensitivity also relates to Akama’s use of the Japanese concept of Ma, ‘between-ness’, to explore how designers can work through processes of becoming together (2015). Kambunga et al. (Citation2023) propose a safe space as a ‘consciously developed social environment for thoughts, situated actions, and mutual learning that allows participants both to engage in dialogues about their everyday experiences, tensions, and contested pasts, and consequently to imagine and co-create alternative and plural futures’. Here, the theoretical contribution is focused on the dialogue, mediated by Country, rather than the temporal and environmental dimension of space—yet there are many parallels in both ontological and relational underpinnings. The continued expansion of these discourses around learning and researching together through dialogue offer a valuable place of grounding alternative ways of knowing and co-designing towards a decolonial and pluriversal participatory practice.

4. Learning and unlearning design in Ntaria

For non-Indigenous researchers, engaging in co-designing on Country necessitates both a reflexive and relational approach based on respectful and ethical interactions (Barton Citation2004). Nagar emphasises the researcher’s need to reconceptualise their place within collaboration as ‘a fissured space of fragile and fluid networks of connections and gaps’ (2003, 359). Being reflexive therefore requires an appreciation of the ambiguity and fluidity within participatory and collaborative research. Kowal (Citation2006) argues researchers can find reflexive processes painful and experience feelings of vulnerability, but it is these feelings that lead to necessary negotiations within the research space and prove a commitment to Indigenous research practices.

Therefore, I begin by detailing my positionality as a woman of Anglo/Celtic heritage born on the lands of the Wodi Wodi people of the Yuin Nation in the land now called Australia. Education has been a strong value in my family, but Indigenous histories, knowledges, and perspectives were largely absent within my own training and practice. Through working with Aboriginal colleagues on First Nations health and political campaigns, I became aware of the lack of Indigenous voices within communication design and design education, and the power of representation and self-determination. Engaging with Country and Indigenous onto-epistemes as the foundation for research necessitates firstly acknowledging the limitations of using a colonial language and my position as a settler within Australia (for a more detailed description of my positionality see St John Citation2022b, Citation2023).

I came to be in Western Arrarnta Country through an introduction from a Western Arrarnta colleague and friend who connected me to Ntaria School who were interested in digital literacy training for their senior students. Ntaria is a small Aboriginal community within the traditional lands of the Western Arrarnta people, the custodians of Central Desert Country. Initially visiting the community in September 2016, the school wanted to ensure student voices were included in the development of the programme, was relevant to the skills they wanted to learn, and there was wider community support and permission for my stay. This visit was spent chatting to students and staff, becoming known, listing, and developing a plan around student aspirations, and what useful skills I could share.

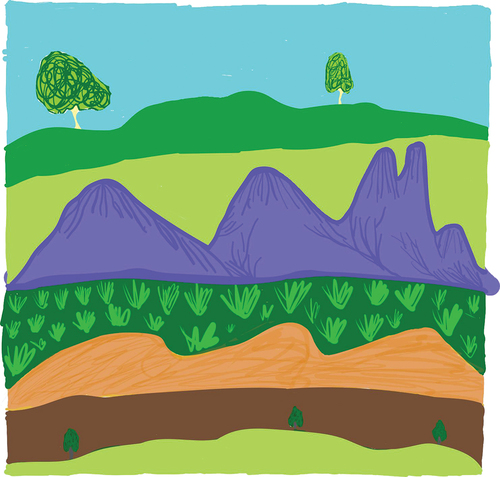

An initial education framework for the design workshops was then developed prior to fieldwork and focused on being engaged in the local (see ). Connecting learning to Country draws from a place-based educational approach, in which ‘the place provided the context for learning’ (Coleman Citation2014, 5). From this perspective, Western Arrarnta Country became the basis of the educational approach and the students’ introduction to digital drawing within a contextualised learning environment.

I returned to Ntaria School in April 2017 with institutional ethics and approvals and community support for the project, yet the research became negotiated and mediated by Western Arrarnta Country (St John Citation2022c). My original six-week plan soon became more fluid and flexible, as I began to un-learn my euro-centric approaches to design, research, and teaching and re-learn how to be on Country, which I unpack within my reflections below. Ultimately, the workshops were held with 16 students aged 14–18 two days a week, across 2017 and 2018 (St John Citation2020). Data was collected across mixed participatory modes including observational, oral, and visual modalities with an emphasis on personal narratives, reflection, and story sharing (St John Citation2022b). Workshops focused on storytelling through digital drawing and learning digital design tools such as the Adobe range of programmes. The ‘doing’ of researching, teaching, and learning became an iterative, negotiated process that emerged through spending time together, building trust, and being on Country. The findings below present a re-evaluation of the initial Ntaria Design Education Framework (see ) to provide a more reflexive, relational, and collaborative approach to communication design education within Ntaria School.

5. Purta ngkarrama: In dialogue together

Here, the Western Arrarnta concepts of purta ngkarrama, of people talking together in dialogue, and purta kaltjerrama, of people learning together, are explored as co-design practice. Here, the focus is on my own journey, in listening, un-learning, and participating, to be able to engage in meaningful dialogue on Western Arrarnta Country. The self-reflective dialogue presents an approach to participation that is enacted in relation to place, context, knowledge, and relationships. Engaging in reflexive practice as an analytical method for generating the knowledge shared within this paper draws on approaches and tools from codesign and Indigenous scholars, who ask researchers to acknowledge, analyse, and take responsibility for often uncomfortable, embodied, and emotional responses to the tensions, conflicts, and tensions that arise within participatory research (Reitsma Citation2021; Kovach Citation2017). Reitsma’s ‘reflective making’ tools suggest ways that researchers can engage in dialogue with themselves and their experiences, drawing on reflection-in-action (Schon Citation1983), interconnected critical reflection and action (Freire Citation1970) and sense-making (Dervin Citation2003). Kovach undertakes critical self-reflection through journaling, as a tool for making meaning. Rather than just capturing observations, journaling offered a space to capture ‘reflections on thoughts, relationships, dreams, anxieties, and aspirations in a holistic manner’ and a method for ‘tracing personal analysis and discoveries of the research that were emerging in narrative’ (Citation2009). The analytical method used here draws from both approaches, utilising journaling techniques and engaging in dialogue with the self as a form or personal analysis, way to trace discoveries, and develop thematic narratives.

The use of Western Arrarnta language words within this narrative speaks to the importance of capturing a respectful and reciprocal approach to co-designing together, and reflects the importance of language and intercultural understandings, which became apparent throughout my own learning journey. The Western Arrarnta words and phrasings used within the paper are themselves an offering, and were specifically gifted to the researcher within a personal relationship (St John Citation2022b). They are used here as a concept for mutual understanding, and reflect how my own ontological transformation was required to be able to engage in dialogue together on Country. Key learnings from my personal reflexive practice are grouped in four narratives: (1) In dialogue with Country, (2) In dialogue with the Ntaria community, (3) In dialogue with the students, (4) In dialogue with design education. While these narratives are placed within distinct thematic dialogues, they are also inter-connected, as being in dialogue with Country also affects being in dialogue with community, which also affects being in dialogue with students, for example. Whilst these dialogues can be read holistically, as they exist in relation to each other, they are grouped here to learnings that emerged from reflexive practice.

5.1. In dialogue with country

Acknowledging and developing an awareness of Western Arrarnta Country became fundamental in maintaining relationships, holding and sharing knowledge, and shaping research practices. Rather than a central focus in an education framework, learning together on Country became a way of engaging in research, learning, and teaching that was enacted in everyday life.

Being on Country required that I adopt an iterative approach to lesson delivery and research activities as the weather, seasons, and cultural events largely dictated how the design workshops unfolded. During wet season, the roads in and out of the community would flood and be impassable, when langwa or bush bananas were in season, students were often missing from the classroom, and when community events or cultural ceremonies were happening, I would not see any students for weeks. Yet the flood waters enabled the regeneration of grasses and plants, harvesting langwa meant students were often drawing them in the classroom and sharing the stories of important bushfoods, and cultural ceremonies were integral moments of intergenerational knowledge sharing and cultural continuity for Western Arrarnta people. This slower pace forced me to slow down and appreciate the rhythms and knowledge embedded in Country.

Over time, students began to invite me onto bush trips. Often initially pitched as ‘going outside to be inspired’ they often turned into extended all-day adventures where we would set off on the school troopy (4WD bus), stop in what seemed to me to be the middle of the bush, take long walks to collect bush foods, and the students would share stories of Country (see ). At first writing these trips off as an excuse to get out of the classroom, I came to realise it gave students space to think about the meaning and relevance of the signs and symbols they used in their design work, and how they related to both Western Arrarnta traditions and their contemporary lives. Students would often comment:

I like design because I like drawing and drawing my country makes me feel good. It is important to tell these stories. (Student 1)

My design tells stories of culture and bush tuckers. Things that are important to me. My designs are about culture. Dreaming. They are all from this place. (Student 2)

My design is of different bush tuckers around Ntaria. It is a beautiful Country. (Student 3)

Centring Country was for me about being open and taking time to physically be on Country, to listen to the students to share their knowledge of Country, and to see how this knowledge was enacted through their design outcomes. Moreover, premising design on Country enabled the young adults to recognise their own experiences and processes, and engage as knowledge holders and protectors of the Western Arrarnta culture.

Co-designing in Ntaria was centred by Country. This was the most fundamental difference in approaching teaching, learning, and collaborating. Is it not ‘user-centred’ or ‘human-centred’ but Country-centred, or how things relate to and are informed by Country. As Yuin scholar Dr Daniele Hromek (Citation2020) describes:

Country incorporates both the tangible and the intangible, for instance, all the knowledges and cultural practices associated with land. People are part of Country, and their/our identity is derived in a large way in relation to Country/Their/our belonging, nurturing and reciprocal relationships come through our connection to Country.

Aboriginal Academic Norm Sheehan details how Country grounds the purpose and enactment of design for Aboriginal people (Citation2011). That designing on Country builds relationships with Indigenous knowledges, as ‘our design has always been nurtured and informed by this natural intelligence’ (Sheehan Citation2011, 76). On-Country design contrasts with dominant colonial conceptions, in which cultural knowledges, histories, and identities are marginalised in favour of design as an object, process, solution, or profit-making endeavour (Schultz et al. Citation2018). These deeply spiritual notions of Country raise the question of how non-Indigenous researchers can ethically engage in co-designing within this profound existence of place?

While designing on Country has direct implications and impacts not just for what and how design is taught and approached, it also acts as the premise for non-Indigenous people to engage lawfully and relationally for research to take place.

5.2. In dialogue with the Ntaria community

The Ntaria community engaged in the design workshops in ways that were largely unplanned and unforeseen, from initial conversations in the community, to visits to the classroom, to sharing stories, and to mentoring students. While initial conversations with the wider community happened before the design workshops started, the connections and relationships that developed took time in developing trust and understandings and in creating spaces where community members felt comfortable in coming and sharing, of looking, engaging, and supporting the students’ design work. This community engagement was unstructured but instrumental. There was no formula or step-by-step guide – it happened in very ordinary ways over conversations, becoming known, meeting parents, sending students home with examples of their work, and welcoming community to come to the classroom. The students also clearly expressed a connection of designing to the maintenance of family relationships and community knowledge. As three of them expressed:

My grandmother sees my design and that I am following in her footsteps, and she says, ‘I’m proud!’ (Student 4)

I can tell culture stories through design that I have learnt from my great-grandmother. (Student 1)

When I show my family my work they say, ‘oh my goshhh’, they say, ‘I feel proud for your work’ and ‘I’m so proud you’re doing that thing with your art’. (Student 8)

The support of the students' families was instrumental regarding the stories and knowledge shared within their digital drawings, and feelings of connectedness and pride. In particular, the artists working at the Hermannsburg Potters, a local Aboriginal-run community art centre, took a particular interest in the project, in watching students draw in digital ways, and observing what kinds of stories they were sharing. Their comment of ‘Marra – good one’ was a sign of respect for the students that their work was not only of a high standard but was respected and had value within the Ntaria community, not just within the classroom. The potters also came to guide me, through sharing stories of the community, the Western Arrarnta culture, and Ntaria history, and explain some of the stories and meanings behind the student designs. They also endorsed the programme and students’ design work within the community through ongoing conversations with parents, families, and elders.

The relationships with the school were also paramount to the success of the programme. Having the support of the teaching staff within the classroom, particularly around the flexibility of the approach, enabled the programme to develop in an iterative fashion, and to develop connections to curriculum that were meaningful for the students and for Ntaria School. However, high staff turnover, reluctance of some staff to engage with technology, and their misconceptions of design meant relationships and dialogues took time to rebuild and develop each teaching period. The lack of continuity also meant working with new staff at the start of each new term, unknown to students and the wider community, and re-moulding the programme to fit their own personal teaching approach and particular areas of interest within the classroom. Being situated within the classroom required flexibility, in bringing new staff up to speed, allowing the students to show new teachers their skills and outcomes, and being open to teaching staff implementing new plans, or complementary lessons around their design education, so the programme could continue, and be supported by the teaching staff, and their own commitments, curriculums, and priorities.

5.3. In dialogue with the students

While the educational component of the design workshops focused on technical knowledge and skills-based learning, what the students brought enabled the programme to develop and grow according to their interests and aspirations, but also to be connected to Country and community. The students’ engagement with me was underpinned by a ‘passage of time’ and was about slowing down and ‘hanging out’, watching footy, going for drives, or looking for bush tucker. Slowing down meant we began to generate ongoing dialogue. It allowed time and space for me to recognise that design in Ntaria had its own distinct meaning and process. For me, this catalysed a questioning of dominant understandings of design and support the students to design according to their own worldviews, by enabling them to choose their own design tasks and beyond being prompted to ‘tell a story’ were given no further direction pertaining to completion timeframes, collaboration, or what the outcomes needed to include (St John Citation2023). This openness and encouragement to explore their own ways of designing worked to reveal how design can enact distinct local, cultural, and relational processes, as the Ntaria students connected to, reflected on, and transmitted Western Arrarnta knowledge to create tangible expressions of culture (St John Citation2023). By listening and dialoguing around our different perspectives and ways of designing, I began to see more clearly my own positions and responses, and in turn acknowledge how design in Ntaria refers to a more expansive creative practice than currently defined by Westphalian boundaries or qualifiers (St John Citation2023). Throughout the design workshops, the Ntaria participants spoke to how they experienced ‘design’ as simultaneously similar and different to other Western Arrarnta creative practices (see St John Citation2020). They explored how their ideas and knowledge lie ‘beneath’ any medium, but the design offered a ‘newness’ inherent within creating on a digital surface, and outcomes made possible through digital mediums (St John Citation2020). Arts-based researcher Patricia Leavy describes this process for participants as making the strange familiar and for the researcher, making the familiar strange (Leavy Citation2017, 658).

Yet, not all students engaged with the design programme, and there were certainly times when students became disengaged, attendance dropped, and students left the community to come back weeks or months later. There were those who felt shame about their work, which acted as a barrier to their success within the programme, and its focus on identity and story, as they felt their digital drawing skills or the digital drawing tools did not enable to create what they had envisioned. This was often addressed by enabling students to continue drawing by hand, while continuing to learn basic digital drawing tools and functionality, before bringing concepts onto the digital screen. The Aboriginal English term ‘shame’ differs from non-Aboriginal use and can incorporate ideas of getting shame when meeting strangers, or in the presence of relatives within kinship systems, entering an unfamiliar place, being shy, bashful, and being respectful of Elders or authority figures (Harkins Citation1990). Harkins also notes concepts of shame in relation to education can be around being singled out for any purpose, including praise, scolding, or simply attention (1990). In the classroom, it was important to understand these intercultural differences, to give students time and space, to walk away, to talk to family, and to partake in the design workshops at times when they felt ready. This time in thinking, talking, and engaging when students felt ready also effected the design process, where students foregrounded storytelling, and feeling strong in their cultural and family knowledge before creating a design on paper or the iPad (St John Citation2023).

For me, coming to this understanding involved a process of ‘undoing’ – rethinking my acceptance of teaching and learning behaviours (Somerville Citation2007, 230). It required a value-based personal commitment to representing the students in my research in ways they wanted to be represented. It required a value-based personal commitment to representing the students in my research in ways they wanted to be represented, and remaining reflexive to prioritise this throughout the research. For Western Arrarnta people, relationships form and show how things are connected, known, and shared. Relationships and the building of trust and care also determined how the study preceded and what knowledge was shared. Bull (Citation2010) describes this as an authentic research relationship, which is committed to, ‘employing processes that allow the researcher to learn and be responsive to an Aboriginal mindset’ (17). An approach to learning design in Ntaria emerged that was responsive to the challenges and opportunities that presented themselves along the way. Navigating this terrain ultimately guided the overall ‘doing’ of the study. It was how co-designing emerged in the field, on Country, in the everyday, and within the lived realities of young adults. Here, codesign emerged and occurred through relationships.

5.4. In dialogue with design education

Situating design education within a dialogue between relational connections of Country, students, design, and the wider community required teaching to be responsive to these elements. As Karen Martin (Citation2005) argues, educators must work from a framework that holds relatedness at its core, acknowledging how schooling as a Eurocentric institution relies on Eurocentric frameworks for education and Western models of development, which impeded relatedness in the context of teaching and is inappropriate for Aboriginal ways of learning (Martin Citation2005).

Becoming relational required a reflexive approach to teaching, being aware of the ways in which Eurocentric perspectives have been embedded within communication design education and practice. It often meant feeling uncomfortable as I was forced to reconsider my own understandings and ways of teaching, to enable spaces for the students to come to design and work within their own imaginings. Viewing Indigenous knowledges as an inclusive and sophisticated system, rather than a limitation or obstacle to teaching, was imperative. This approach honoured Indigenous knowledges as well as the dominant systems, tools, and technologies of communication design. The focus on digital skills acquisition facilitated experimentation with drawing techniques, colours, styles, and shapes. And while the student’s experiences and subsequent outcomes are framed by the educational focus on digital drawing and working with the Adobe range of applications on an iPad, these tools and skills were meaningful for the Ntaria students through the combination of skills-based learning of digital tools with sharing cultural knowledge (St John Citation2022a, Citation2022c, Citation2023). The students expressed a sense of newness and difference enabled from working with digital tools and outcomes, but also an enabling of established cultural practices, and the ability to recreate traditional knowledge. Ultimately, design education enabled the participants to create their own visual representations of their contemporary Aboriginal identities (St John Citation2022a). Students, such as the one quoted below, often noted the important relationship between learning and cultural knowledge:

We are learning. Getting new skills. We are designing and making our own things. It’s important for people to know our culture. To respect our culture. To respect us. (Student 1)

My role also focused on sharing and teaching digital drawing skills and techniques while troubleshooting any means of technical problems. Practical experience here was essential, as my ‘designer’ knowledge accumulated through years working within the communication design industry enabled the more technical aspects of working with vectors, saving, and storing files, as well as associated printing and production requirements to be a smooth process. By integrating Western Arrarnta knowledges with design expertise and training, the dynamics between our value systems were respected and it catalysed my own ontological transformation through mutual knowledge sharing. Coming to understand that the Western Arrarnta language does not include any words that distinguish between art, craft, and design raised questions of how creative expression is not universal to all cultures. Alternatively, we can position and understand that design has always been taking place, rooted in local practices, but perhaps existing by another name (Akama and Yee Citation2019). Positioning design on Western Arrarnta Country situated ‘ways of designing’ beyond Westphalian boundaries. Yet it is not the intention here to ‘other’ or add to a binary two-culture rhetoric, in defining Ntaria ways of designing, and then comparing them to euro-western approaches. My positioning here acts as a response to the problematic acceptance of any ‘universal’ understanding of design towards a ‘multiplicity of local actions’ (Escobar Citation2018) where many realities and ways of designing can co-exist (see also Leitão and Noel Citation2020).

Being in dialogue facilitated an expansion, a coming, working, and building educational programmes together for the benefit of design that values, respects, and prioritises the knowledge systems, and ways of being, knowing, and doing of Indigenous people. By enabling and prioritising students to bring local cultural perspectives to their learning and work within their own processes, the design workshops focused on student achievement and success according to factors important in Ntaria, such as the ability to tell stories through digital drawing. The learning outcomes were not based on their understanding of Eurocentric design, or their ability to match styles of abilities of non-Indigenous students, but were instead focused on students expressing their identities, telling stories through design, and creating designs from a Western Arrarnta worldview (see ). My role as a design educator crucially focused on supporting distinct Ntaria perspectives of design as they emerged through the design workshops. As a cultural outsider, this required listening, taking time, and learning about the students and their place within the community. It meant encouraging students to share their voices, cultural stories, and knowledges, to explore their own processes and ways of designing. It meant acknowledging the importance of story, family, and culture and to allow these connections and relationships – of knowledge and Country – to guide our collaborative learning journey.

6. Discussion: positioning co-design as relational dialogue

Purta ngkarrama, or a collaborative dialogue, presents a way of approaching co-design, beyond a methodology to apply, but as a personally embodied ontological practice. Importantly, purta ngkarrama, is a way of co-designing on Western Arrarnta Country that is contextually specific and located within personal relationships. In this way, situating collaboration as ongoing dialogue is rooted within place and personhood. It is not a framework or process that cannot be ‘applied’ by an invisible researcher from nowhere (Moran, Harrington, and Sheehan Citation2018; Suchman Citation2002). Too often the design represents complex relationships as simplified frameworks, offered as a solution to be reproduced (Akama, Hagen, and Whaanga-Schollum Citation2019). Yet being in dialogue requires being present and listening deeply, and centring a worldview that considers establishing, nurturing, and being accountable to people as individuals, as members of communities, and extends to the knowledge that participates in and with other entities in the environment (Smith Citation2005). Being in dialogue presents a way of co-designing that is an active sharing of knowledge.

Engaging in dialogue raises fundamental questions in relation to how researchers, academics, and designers can bring and exchange useful knowledge in meaningful ways. Critically reflexive research praxis by non-Indigenous researchers is required, in wrestling with discomforts or ‘white fragility’ in not being the owner or expert of design knowledge which ontologically emerges from Country (West Citation2020). Engaging lawfully on Country requires a continual questioning of what I can know and how I design, research, teach, and learn in relation to multiple knowledges and truths.

This emergent journey of learning also supports the notion that validity lies in how researchers implement and embody co-design methodologies (Lincoln and Guba Citation1994). As it is not a specific methodology that ensures validity or ethical practice, but rather its use that creates spaces where everyone is welcome, where relationships of respect and trust are created (Bat Citation2008). Being in dialogue also offers an approach that honours the situated entanglements that are often unanticipated but confronted in the field. This is a challenge to projects with pre-set methods and constrained timelines, as it requires giving up control, or perhaps patience to allow things to unfold and occur when the time is right – rather than quickly jumping to solve problems or ‘gather’ data. Therefore, it is essential to document the knowledge that emerged, and where relationships of respect, trust, and care are created through doing co-design together. Enacting co-design on Country offers a way to open up more discussion and learn from others in unsettling dominant research practices to practise reciprocity and care.

7. Contributions to pluriversal co-design practices

The enactment of local and culturally led approaches to co-design provides an opportunity for the expansion of collaboration and reciprocity into academic, industry, and government contexts. It questions how design education can be informed by local, cultural, and spiritual processes and how pluriversal ways of designing can reshape and expand current understandings of what it means to design, and provide a route to more innovative and sustainable design practices and outcomes within industry.

Yet experiences of embodied and transformational practice can be hard to communicate, in part due to resistance or misalignment with Western approaches to participation and knowledge sharing. Design, too, is challenged in response to local words, and that Indigenous knowledges cannot be fully translated or explained into the Western Design logics. This in turn can often limit the scope of pluriversal approaches to co-design and presenting alternative ways of being and engaging in participatory research, which do not smoothly fit in the transactional nature of many project-based design relationships. However, more detailed accounts of how to start, put into action, maintain, and reflexively respond to pluriversal enactments such as those offered here are emerging within co-design discourses, and accounts of researchers embracing complexity and promoting reciprocity continue to expand the discipline (see also Muashekele et al. Citation2023). Particularly those, which centre on knowledge, wisdom, and lifeways of Indigenous peoples worldwide, provide a valuable place of grounding and understanding into alternative ways of knowing, learning, and engaging in respectful collaboration.

Premising Indigenous worldviews and onto-epistemes acknowledges unceded lands, invitations to work alongside community and Traditional Custodians, and accepting laws and obligations to relationships on and with Country (West Citation2020). Here, Indigenous sovereignty precedes modernity, and rather than seeking to decolonise co-design as the focus, it offers a practice mediated by relationships within local contexts and respecting local ways of doing things. Grounding Indigenous knowledge protocols within co-design learns from many First Nations and non-Indigenous people working together on many unceded lands all over the world (e.g. Albarrán González Citation2020; Hernandez Ibinarriaga Citation2020; Ngā Aho Citation2016 and more).

The personal dialogues shared here are positioned as a response to the problematic acceptance of ‘universal’ understandings of design and participation, hoping to add to discussions of enacting design plurality through sharing personal narrative reflections through practice. Being in dialogue encourages expanding understandings and considerations of how research can acknowledge and engage with places, cultures, knowledges, and ways of designing. These dialogues also highlight the importance of detailing processes of building relationships and rapport with others, including with place and community, thinking, conversing, being together, and showing care, which tends to be typically removed from conventional academic accounts, despite it being essential to the maintenance of reciprocal, respectful, and accountable research relationships and collaborations, as well as personal ontological transformations. Highlighting personal tensions and how these led to both ontological transformations and methodological shifts, such as those shared here, are crucial to identify and reflect on, so we can discuss and broaden the understandings of how we might further enact pluriversal and decolonial ways of researching and collaborating within the field. In sharing, I hope to encourage and to learn from others in unsettling dominant practices to promote a plurality of perspectives of meaningful dialogues within co-design practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akama, Y., P. Hagen, and D. Whaanga-Schollum. 2019. “Problematizing Replicable Design to Practice Respectful, Reciprocal, and Relational Co-Designing with Indigenous People.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 59–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2019.1571306.

- Akama, Y., and J. Yee. 2019. “Embracing Plurality in Designing Social Innovation Practices.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 1–11.

- Albarrán González, D. 2020. “Towards a Buen Vivir-Centric Design: Decolonising Artisanal Design with Mayan Weavers from the Highlands of Chiapas, Mexico.” Auckland University of Technology. https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/13492.

- Barton, S. S. 2004. “Narrative Inquiry: Locating Aboriginal Epistemology in a Relational Methodology.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 45 (5): 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02935.x.

- Bat, M. 2008. “Our Next Moment: Putting the Collaborative into Participatory Action Research.” In Changing climates: Education for sustainable futures. Proceedings of the 289 AARE 2008 International Education Research Conferenc, edited by P. L. Jeffery. Brisbane, QLD: Australian Association for Research in Education.

- Bohm, D., and R. A. Weinberg. 2004. On dialogue. Routledge.

- Bull, J. R. 2010. “Research with Aboriginal Peoples: Authentic Relationships as a Precursor to Ethical Research.” Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 5 (4): 13–22.

- Chow, W. 2007. “Three-partner dancing: placing participatory action research into practice within and indigenous racialised & academic space.“ PhD diss.

- Coleman, T. C. 2014. Place-Based Education: An Impetus for Teacher Efficacy. Western Michigan University.

- Dankl, K., C. Akoglu, and K. Bro Egelund. 2023. “A Contemporary Framework for Probing in Social Design: On Continuous Dialogues and Community Building.” CoDesign 19 (1): 14–35.

- Dei, G. J. S. 2014. “Indigenizing the curriculum: The case of the African university.” In African indigenous knowledge and the disciplines, 165–180. Brill.

- Dervin, B. 2003. “A Sense-Making Methodology Primer: What is Methodological About Sense-Making.“ In San Diego, California: Meeting of the International Communication Association.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by MB. Ramos. New York: Continuum.

- Gunn, W., T. Otto, and R. C. Smith, Eds. 2013. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Harkins, J. 1990. “Shame and Shyness in the Aboriginal Classroom: A Case for “Practical semantics”.” Australian Journal of Linguistics 10 (2): 293–306.

- Hernandez Ibinarriaga, D. 2020. “Critical Co-design Methodology: Privileging Indigenous Knowledges and Biocultural Diversity (Australia/Mexico).” PhD Thesis, Deakin University. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30136596.

- Hromek, D. 2020. “Defining Country. Designing with Country.” aila.org.au

- Jones, P., A. Christakis, and T. Flanagan. 2007. “Dialogic Design for the Intelligent Enterprise: Collaborative Strategy, Process, and Action.” International symposium of the international council on systems engineering, 1–16. San Diego, CA: INCOSE.

- Kambunga, A. P., R. C. Smith, H. Winschiers-Theophilus, and T. Otto. 2023. “Decolonial design practices: Creating safe spaces for plural voices on contested pasts, presents, and futures.” Design Studies 86:101170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2023.101170.

- Kovach, M. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto press.

- Kovach, M. 2017. “Doing indigenous methodologies.” The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research 383–406.

- Kowal, E. 2006. “The proximate advocate: Improving indigenous health on the postcolonial frontier.” Doctoral diss., The University of Melbourne. https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/39268.

- Leavy, P. 2017. “Introduction to Arts-Based Research.” In Handbook of Arts-Based Research, edited by P. Leavey, 3–21. New York: The Guildford Press.

- Leitão, D. R. M., and D. L. A. Noel. 2020. “DRS2020 Editorial: Pluriversal Design SIG.“

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. G. Guba. 1994. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 105–117. 3rded. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lucero, A., K. Vaajakallio, and P. Dalsgaard. 2012. “The Dialogue-Labs Method: Process, Space and Materials as Structuring Elements to Spark Dialogue in Co-Design Events.” CoDesign 8 (1): 1–23.

- Martin, K. 2005. “Childhood, life and relatedness: Aboriginal ways of being, knowing and doing.” In Introductory indigenous studies in education: The importance of knowing, edited by J. Phillips and J. Lampert, 27–40. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education.

- Moran, U. C., U. G. Harrington, and N. Sheehan. 2018. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture 10 (1): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

- Muashekele, C., K. Rodil, H. Winschiers-Theophilus, and C. Magoath 2023, April. “Futuring from an Indigenous Community Stance: Projecting Temporal Duality from the Past into the Future.” In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany. 1–7.

- Ngā Aho. 2016. “TONO: What is Our Tikanga for Aotearoa Co-Design? What Does a Tikanga Māori Co-Design/social Innovation Practice Like?.” https://ngaaho.maori.nz/page.php?m=187.

- Nieusma, D. 2004. “Alternative Design Scholarship: Working Toward Appropriate Design.” Design Issues 20 (3): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1162/0747936041423280.

- Noronha, J. V., and K. Niinimäki. 2017. “Design probes applied as fashion design probes.” In Opening up the Wardrobe: A Methods Book, 84–86. Novus Forlag.

- Reitsma, L. 2021. “Making Sense/Zines: Reflecting on Positionality.” In Pivot Conference 2021 , 317–329.

- Rodil, K., H. Winschiers-Theophilus, T. I. Asino, and T. Zaman, eds. 2019. “Indigenous Knowledge and Practices Contributing to New Approaches in Learning/Educational Technologies.” Special Issue, International Journal on Interaction Design & Architecture, S (41).

- Schon, D. A. 1983. The Reflective Practicioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Schultz, T. 2018. “Mapping Indigenous Futures: Decolonising Techno-Colonising Designs.” Strategic Design Research Journal 11 (August): 79–91. https://doi.org/10.4013/sdrj.2018.112.04 .

- Schultz, T., D. Abdulla, A. Ansari, E. Canlı, M. Keshavarz, M. Kiem, de O. Martins L. P, and de Oliveira, P. J. S. V. 2018. “What is at Stake with Decolonizing Design? A Roundtable.” Design and Culture 10 (1): 81–101.

- Sejer, O., K. Halskov, and W. L. Tuck. 2012. “Values-led participatory design.” CoDesign 8 (2–3): 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.672575.

- Sheehan, N. W. 2011. “Indigenous Knowledge and Respectful Design: An Evidence-Based Approach.” Design Issues 27 (4): 68–80.

- Smith, L. T. 2005. “Building a Research Agenda for Indigenous Epistemologies and Education.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 36 (1): 93–95.

- Smith, R. C., H. Winschiers-Theophilus, D. Loi, A. Paula Kambung, M. Samuel Muudeni, and R. de Paula. 2020. “Decolonising Participatory Design Practices: Towards Participations Otherwise.” In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020-Participation(s) Otherwise-Volume 2, Manizales, Colombia. 206–208.

- Somerville, M. 2007. “Place literacies.” The Australian Journal of Language & Literacy 30 (2): 149–164.

- St John, N. 2020. “Ntaria Design: A Western Arrarnta Imagining of Digital Drawing and Communication Design.” Doctoral diss., Swinburne University of Technology. https://researchbank.swinburne.edu.au/items/9b43eb8c-c32b-4e92-8c96-6d1c3cb9f349/1/.

- St John, N. 2022a. “Designing on Western Arrarnta Country: The Ntaria Digital Drawings in.” Design and Culture 14 (3): 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2022.2106348.

- St John, N. 2022b. “‘I Can Put My Culture on My T-shirt’: The Value of Design and Enterprise in Ntaria.” Design Journal 25 (4): 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2022.2082127.

- St John, N. 2022c. “Working Together with ‘Ilkwatharra’ Good Feelings: Beyond Institutional Consent in Participatory Design.” In Participatory Design Conference 2022: Volume 2, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 19 August 2022 – 1 September 2022, Newcastle, United Kingdom.

- St John, N. 2023. “From Anma (Waiting) to Marra (Feeling Good): Ways of Designing in Ntaria in.” Design Studies 86:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2023.101180.

- St John, N., and Y. Akama. 2022. “Reimagining Co-Design on Country as a Relational and Transformational Practice in.” CoDesign 18 (1): 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2021.2001536.

- St John, N., and S. Edwards-Vandenhoek. 2022. “Learning Together on Country: Reimagining Design Education in Australia.” Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education: Studies of Migration, Integration, Equity, and Cultural Survival 16:87–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2021.1907331.

- Suchman, L. 2002. “Located Accountabilities in Technology Production.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 12 (2): 91–105.

- Taboada, M. B., S. Rojas-Lizana, L. X. Dutra, and A. V. M. Levu. 2020. “Decolonial Design in Practice: Designing Meaningful and Transformative Science Communications for Navakavu, Fiji.” Design and Culture 12 (2): 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2020.1724479.

- Till, S., J. Farao, T. L. Coleman, L. D. Shandu, N. Khuzwayo, L. Muthelo, and M. Densmore 2022. “Community-Based Co-Design Across Geographic Locations and Cultures: Methodological Lessons from Co-Design Workshops in South Africa.” In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022-Volume 1, Newcastle, United Kingdom. 120–132.

- West, P. 2020. “Designing in response to Indigenous sovereignties.” In ServDes.2020 - Tensions, Paradoxes, Plurality, 66–79. Melbourne, Australia: Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., N. J. Bidwell, and E. Blake. 2012. “Community Consensus: Design Beyond Participation.” Design Issues 28 (3): 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00164.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., S. Chivuno-Kuria, G. K. Kapuire, N. J. Bidwell, and E. Blake. 2010. “Being Participated: A Community Approach.” In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference, 1–10.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., T. Zaman, and C. Stanley. 2019. “A Classification of Cultural Engagements in Community Technology Design: Introducing a Transcultural Approach.” Ai & Society 34 (3): 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0739-y.