ABSTRACT

The multi-layer safety approach was introduced in 2009 in the Netherlands as a result of the shift from flood prevention to flood risk management. It aims at reducing flood risks by integrating defensive measures against floods (layer 1), resilient spatial planning measures (layer 2), and effective disaster management measures (layer 3). But how are these measures integrated? This contribution explores that question with a qualitative case study in Zwolle. In particular, policy and territorial integration among the multiple stakeholders are analysed. The analysis shows that the defensive approach (layer 1) still prevails, but that flood risk management is integrated into spatial planning (layer 2) in terms of policy integration and territorial integration. That is not the case for disaster management (layer 3), which remains detached from the other two layers. This contributes to the debate on integration in water management with other sectors through an in-depth analysis.

1. Introduction: a spatial turn in Dutch flood risk management

Urban areas located near rivers or coastlines are highly vulnerable to floods due to their population and valuable land uses (Tempels & Hartmann, Citation2014; Voskamp & Van de Ven, Citation2015). The Netherlands, being a densely urbanized country located in the delta of the rivers Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt, is vulnerable to floods both from the coast and rivers (Ritzema & Van Loon-Steensma, Citation2018; van den Brink et al., Citation2011; Woltjer & Al, Citation2007). Until the 1990s, the Dutch government mainly applied defensive measures against floods, such as dikes and barriers (Baan & Klijn, Citation2004; Neuvel & van den Brink, Citation2009; Pötz et al., Citation2014). After major river floods in 1993 and 1995, the Netherlands started to embrace a risk-based approach (Ritzema & Van Loon-Steensma, Citation2018; Woltjer & Al, Citation2007). This was institutionalized on the European level with the Floods Directive (2007/60/EC).

The multi-layer safety approach was then introduced in 2009 in the Dutch National Water Plan (Ministry of Public Transport and Water, Citation2009) and fits the notion of integrated flood risk management pushed by the European Floods Directive (2007/60/EC) (De Moel et al., Citation2014; Hartmann & Spit, Citation2016; Hoss et al., Citation2011; Kaufmann et al., Citation2016; van Herk et al., Citation2014). It consists of three layers.

The first one aims at defending from floods (preventive-structural measures), the second one focuses on spatial adaptation (resilient spatial planning) and the third one on evacuation and disaster management (Kaufmann et al., Citation2016; Van Buuren et al., Citation2016; van Herk et al., Citation2014).

In the Netherlands, measures of the three layers tend to be implemented separately from each other, and prevention is still widely considered as the most effective approach in flood risk management in the general public perception (Neuvel & Van Der Knaap, Citation2010; Van Buuren et al., Citation2016). The multi-layer safety approach aims to integrate flood prevention with resilient spatial planning and disaster management to decrease both probability and consequences of flooding within one approach (De Moel et al., Citation2014; van Herk et al., Citation2014; Zandvoort & van der Vlist, Citation2014). This integration implies a combination of different policy sectors that belong to water authorities, spatial planning authorities, and disaster management authorities (van Herk et al., Citation2014; Zandvoort & van der Vlist, Citation2014). However, while integration between the layers is central in the multi-layer safety approach, the concept is not explicit on the exact relation between the layers or how this integration should take place. Sectoral-policy integration and collaboration among different stakeholders often result in indecisiveness and conflicts of interest, thus affecting and delaying policy processes (Scholten et al., Citation2020). For instance, the combination of measures of the three layers (e.g. dikes, water-proof buildings, and effective escape routes) can be hampered by the need to share responsibilities and funding among stakeholders (Pötz et al., Citation2014). At the same time, integration is considered the solution to achieve flood risk management plans, which remain otherwise fragmented and not suitable for a risk-based approach (Cumiskey et al., Citation2019). For these reasons, a clear understanding about integration of flood defence, spatial planning, and disaster management is seen by policy and academia as essential for the success of the multi-layer safety approach, as it will be discussed in the next section.

The objective of this paper is to explore the state of integration between the different layers of the multi-layer safety approach by analysing its processes during the development of a flood risk management plan. The investigation is carried out through a case study in the Dutch city of Zwolle, where interviews about processes of the multi-layer safety approach were conducted with stakeholders involved in the development of a flood risk management plan, and related official documents were analysed.

2. Multi-layer safety approach and integration

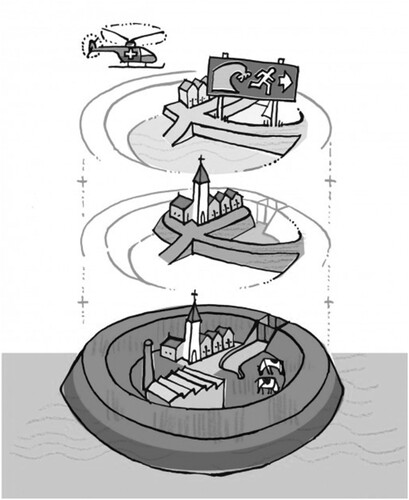

The multi-layer safety approach () embodies spatial planning and disaster management in addition to the structural measures always adopted, by forming three different layers (De Moel et al., Citation2014; Hoss et al., Citation2011; Pötz et al., Citation2014; Ritzema & Van Loon-Steensma, Citation2018; van Herk et al., Citation2014). It is important to specify that measures of layer 2 and layer 3 neither substitute nor change the preventive ones of layer 1, they rather work as additional support for preventive measures (Kaufmann et al., Citation2016; Pötz et al., Citation2014; Ritzema & Van Loon-Steensma, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Schematization of the layers of the multi-layer safety approach (Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Citation2009). From bottom to top: Layer 1 (preventive-structural measures) aims at avoiding waterlogging through structural measures (e.g. dikes and barriers); Layer 2 (resilient spatial planning) contributes to reducing the negative effects of flooding through the physical spatial structure, (e.g. elevated buildings); Layer 3 (disaster management) aims at helping the society in case of a disaster occurs with evacuation measures (e.g. disaster plans and risk maps).

This major importance of layer 1 derives from the strong focus of Dutch governments on a traditional approach which is mostly a technical-engineering one (Jong & Brink, Citation2017). However, the European Floods Directive pushes the member states toward integration of water management into spatial planning because land uses are strongly affected by flood plans and scenarios, especially in the Netherlands due to its hydrological and geographical features (Hartmann & Spit, Citation2016).

Resulting from this push, the multi-layer safety approach aims at integrating flood prevention into spatial planning (e.g. with waterproof buildings) and disaster management (e.g. with prompt evacuation plans) for an effective reduction of short-term and long-term flood risk (van Herk et al., Citation2014).

Starting from its definition, integration means ‘the act or process that combines two or more things so that they work together’ (Hornby et al., Citation1974). Integrated approaches are needed to solve issues that cannot be solved from a singular perspective (Cumiskey et al., Citation2019; Ran & Nedovic-Budic, Citation2016). Scholten et al. (Citation2020) specify that integration in itself does not solve issues related to different modes of governance in urban areas (i.e. land and water). Just bringing different stakeholders at the same table does not connect the water sector with other sectors (Billé, Citation2008). Cumiskey et al. (Citation2019) conceptualize a theoretical dimension and a practical dimension of integration in flood risk management, respectively depending by the strength of actors’ relationship and by interventions generated from integrated knowledge and policies. Deepening on these two aspects (actors’ relationships and interventions generated by integrated policies) this paper builds on three dimensions of the integration identified by Ran and Nedovic-Budic (Citation2016). They distinguish (1) policy integration, (2) territorial integration, and (3) institutional integration, whereas this paper focuses on the first two dimensions:

Policy integration describes the synergy between different sectors (in this case the three layers) through the combination of their policies (Kidd, Citation2007). It requires combining policies that belong to different sectors (Sutanta et al., Citation2010). It is relevant for the multi-layer safety approach because it aims at combining the policy goals of the water domain, spatial planning domain, and disaster management domain (van Herk et al., Citation2014).

Territorial integration describes cross-boundary working that encompasses policy coherence across spatial scales namely national, regional, and local; and boundaries between different jurisdictions (respectively vertical and horizontal integration) (Kidd, Citation2007). For instance, water boards (regional authority) and municipalities (local authority) need to collaborate on the same land use plans to manage spatial developments in flood-prone areas (Woltjer & Al, Citation2007).

Institutional integration refers to instruments aimed to facilitate communication and coordination among parties (e.g. efficient telecommunication technologies and geo-information tools). Considering that the specific focus on information and technologies requirements in the work of Ran and Nedovic-Budic (Citation2016) goes beyond the focus of this paper on policy processes and stakeholder interaction, this dimension is omitted for this paper.

provides an overview of the integration dimensions used in this paper.

Table 1. The proposed dimensions of integration for the multi-layer safety approach (adapted from Ran & Nedovic-Budic, Citation2016).

3. Methodology

To explore the state of integration between the different layers of the multi-layer safety approach, a qualitative case study design has been pursued in the Dutch city of Zwolle. Located in the province of Overijssel and the IJssel-Vecht delta area, the city is a pilot study for the Delta Programme aimed at implementing the multi-layer safety approach.

In the Netherlands, there are two major organizations responsible for water management: Rijkswaterstaat is the Directorate responsible for flood defence at the national level, and on the regional level water boards (waterschappen) are responsible to provide safety measures related to the 1st layer for the main watercourses (Kaufmann et al., Citation2016; Pötz et al., Citation2014). Municipalities and provinces are responsible for measures related to the 2nd layer at the local and regional level, whereas measures of the 3rd layer involve, for instance, emergency service providers (Pötz et al., Citation2014).

The Delta Programme (Deltaprogramma) is a coalition between multiple governmental authorities aimed at creating long-term plans for flood risk management, spatial adaptation to climate change, and freshwater supply in the whole Netherlands (Gersonius et al., Citation2016). As part of the Delta Programme plan, there are two main programmes involved in the implementation of the multi-layer safety approach in Zwolle. The first is the Flood Protection Program (Hoogwaterbeschermingsprogramma), formed by Rijkswaterstaat, water board Drents Overijsselse Delta, Province of Overijssel, and the municipality of Zwolle.

The programme is financed by the central government and it focuses on the reinforcement and improvement of dikes. The second is the IJssel-Vecht Delta programme (IJssel-Vechtdelta programma), formed by the province of Overijssel, water board Drents Overijsselse Delta, safety board of Overijssel, and municipality of Zwolle. Most of the funding come from the province of Overijssel and the programme focuses on spatial planning adaptation to floods.

The applied methodology includes a review of official documents, websites, and semi-structured interviews. The search for documents aimed to identify at least one document per each spatial level (national, regional, and local) that contains regulations, policy objectives, and information on activities related to flood risk management plans. Among the documents accessible via internet, the selection was made according to their content that focuses on the processes and outcomes of the multi-layer safety approach in Zwolle, and also according to the suggestion of the interviewees. All of them are written by or with the support of the coalitions mentioned above. The analysed documents are the following:

Delta programme (2018). The annual report of the Delta Programme coalition, describing long-term plans for flood risk management, spatial adaptation to climate change, and freshwater supply in the Netherlands.

Water board Vallei en Veluwe website. Website containing information about the water board responsible for the other side of the river IJssel in the proximity of Zwolle.

Water board Drents Overijsselse Delta website. Website containing information about the flood-protection programme and the water board responsible for the area of Zwolle.

IJssel-Vecht delta: Working on water safety and climate adaptation (IJssel-Vechtdelta: werken aan waterveiligheid en klimaatadaptatie). A report written by the IJssel-Vecht delta programme and published in 2019, containing information about the spatial implementation of the multi-layer safety approach.

Zwolle climate-proof (‘Zwolle klimaatbestendig’). A report written by different stakeholders involved in the development of the new water agenda for Zwolle based on the multi-layer safety approach in 2013.

The interviews were conducted with stakeholders involved in the multi-layer safety approach, that work at different spatial levels of competence (national – regional – local). Ten respondents from seven stakeholders were interviewed. The open-ended questions focus on the interaction between stakeholders and on processes of multi-layer safety they worked on. The interviewed stakeholders and numbers of interviewees per stakeholder are the following:

Layer 1: water management stakeholders

Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (national water authority) (one interviewee)

Rijkswaterstaat (executive agency of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management) (two interviewees)

Water board Drents Overijsselse Delta (regional/local water authority) (one interviewee)

Water board Vallei en Veluwe (regional/local water authority) (one interviewee)

Layer 2: spatial planning stakeholders

Province of Overijssel (regional planning authority) (two interviewees)

Municipality of Zwolle (local planning authority) (two interviewees)

Layer 3: disaster management stakeholders

Safety board of Overijssel (regional disaster management authority) (one interviewee)

As mentioned before, layer 1 and its authorities reflect that traditional and technical-engineering way of working in flood risk management, whereas layer 2 and 3 are added to comply with the notion of integrated flood risk management. The gathered information was coded both deductively and inductively by using information related to policy and territorial integration. The data presented in the results section come from a triangulation of sources (i.e. reviews of documents, websites and interviews). When there is a contradiction between documents and interviews this is highlighted to avoid misunderstandings.

4. Results

In this section the results obtained from the interviews and the review of documents are presented, starting from the perspective of policy integration and following with territorial integration. Aspects of policy integration are identified in the roles and activities of different stakeholders that support (or not) the combination of regulations and goals among the three layers. Based on what respondents declared in the interviews and what was stated in the documents, it can be concluded that some stakeholders covered only one role and worked on activities related to one layer. Others covered a role within multiple layers by supporting policy integration between them (see ). Territorial integration is found in the cross-boundary working (vertical or horizontal) among different stakeholders involved in the implementation of the multi-layer safety approach (see ).

Table 2. Policy integration among layers of the multi-layer safety approach.

Table 3. Territorial integration between stakeholders of the multi-layer safety approach, both within and between the different layers.

4.1. Policy integration

The respondent from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management explains that, together with Rijkswaterstaat, the national government mainly execute stress tests on dikes and develop new standards for them throughout the whole country (layer 1). The Delta Programme report specifies that the Ministry also encourages other partners of the Delta Programme to implement measures of layers 2 and 3 in specific cases, like the one of Zwolle. However, the interviewed member of the national government points out that there is no actual role for the Ministry in activities related to layers 2 and 3.

The reinforcement of dikes in the city of Zwolle is managed by stakeholders of the Flood Protection Program namely Rijkswaterstaat, water board Drents Overijsselse Delta, province of Overijssel and municipality of Zwolle. They coordinate together interventions on existing and new dikes at the city level and the regional level. Respondents claim that the Flood Protection Program is exclusively addressed to interventions of the 1st layer of the multi-layer safety approach and is funded by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. Representatives of Rijkswaterstaat and the province of Overijssel underline that the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta plays the most important role and participates actively in all the activities of the programme. According to the interviews and the website of the Flood Protection Program, the province and municipality are involved in the programme as public advisors.

The municipality of Zwolle collaborates, for example, with the waterboard to realize spatial planning interventions on the new dikes (e.g. bike and walk pathways) to increase their spatial quality. However, these interventions do not aim at flood risk reduction. Within processes of the Flood Protection Program, there is no combination of regulations and goals between layers, thus no policy integration.

In the IJssel-Vecht Delta programme the general goal is to implement the multi-layer safety approach in the IJssel-Vecht delta area, chosen as a pilot area by the Delta Programme. Among its activities, there is the development of a water agenda for the city of Zwolle, created mainly by the municipality and the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta. This water board contributed actively to the creation of goals focused on resilient spatial planning. As reported in the document Zwolle climate-proof, the agenda was based on spatial adaptation strategies to tackle floods in the city through the multi-layer safety approach (e.g. reinforcement and elevation of riverfront public spaces) and it constituted the basis for multiple spatial interventions realized by the IJssel-Vecht Delta programme. Waterboard, province, and municipality combined water safety and spatial planning regulations for the construction of water-robust infrastructures (e.g. new buildings elevated from the ground). Such projects were financed mainly by the province of Overijssel but also by the other members of the coalition. A member of the province explains how the water board changed its perspective about the idea of integrating measures:

… the water board now thinks that it is good to put your cards not only on dikes but, especially when it does not make a lot of extra costs, on other investments related to the other layers.

… the trick is to combine goals, so there are several projects in the city of Zwolle where new houses were built by changing the construction regulations to design buildings water-proof.

However, it seems there is a lack of policy integration with layer 3. The representative of the safety board of Overijssel underlines the presence of emergency plans to be used in case of floods, but the Delta Programme report states how the attention on layer 3 needs to increase and its activities need to be more included in the implementation of the multi-layer safety approach in Zwolle.

There is no finding that suggests a combination of regulations and goals between the disaster management authorities and any of the water or spatial planning authorities. In other words, policies of layer 3 exist but they are not integrated with the ones of other layers.

4.2. Territorial integration

There is both vertical and horizontal integration among the authorities of the Flood Protection Program. For example, the directives for dikes are designed by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management to the other water authorities (national and regional) for the city of Zwolle. Rijkswaterstaat cooperates with the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta to decide where and how the new standards for dikes need to be applied.

Here, spatial planning authorities (province and municipality) are involved in the programme since some interventions on dikes are made within their spatial jurisdictions. Thus, in the Flood Protection Program there is a territorial integration both vertical and horizontal between water and spatial planning authorities. Documents and respondents underline that authorities of layer 3 are not involved in the programme and thus they do not collaborate with stakeholders of layers 1 and 2.

Within the IJssel-Vecht Delta programme, horizontal integration occurs between the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta and the province of Overijssel, and vertical integration between both of them (regional authorities) and the municipality of Zwolle (local authority). The document Zwolle climate-proof states that the collaboration between the municipality and the water board was the key factor for the development of the water agenda in Zwolle and the construction of new water-robust buildings in the city. They interacted with each other by crossing their spatial scales. A member of the municipality of Zwolle explains how different governments worked together for the same area:

… it was like working together in one governance. I work for the municipality and he works for the province, but it does not matter, we worked for the area together.

Despite being formally involved in the programme, the representative of the safety board of Overijssel did not mention any cooperation with other authorities, except for a few meetings. The disaster management authority is also barely mentioned by the others and by the documents.

As confirmed by one of its representatives and by a representative of the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta, there is neither vertical nor horizontal integration between the water board Vallei en Veluwe and other stakeholders.

5. Discussion

This paper looked at the integration between layers of the multi-layer safety approach in the city of Zwolle by focusing on policy integration and territorial integration.

In terms of policy integration, it is notable how none of the stakeholders covers a role only in layer 2 (resilient spatial planning).

The regional and local planning authorities (province and municipality) who are responsible for spatial planning, identify their main role as being integrative, supporting a combination of regulations and goals between the water sector and the spatial planning sector.

Also, the regional water authority Drents Overijsselse Delta supported policy integration of water management into spatial planning by being involved in the development of the water agenda for Zwolle and new waterproof spatial developments in the city. These results may indicate that in terms of policy integration, the stakeholders responsible for layer 2 (municipality and province) support the integration of water safety into spatial planning. This is not the case of layer 1, in which only the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta support policy integration and not the other water authorities, as the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and Rijkswaterstaat focused exclusively on layer 1. Layer 3 seems to be detached from the others and its role is not supportive of policy integration. Strikingly, while some stakeholders such as Rijkswaterstaat and the municipalities have a responsibility in disaster management (e.g. evacuations plan in case of floods), neither the respondents nor the documents mention these responsibilities in the context of the case of the multi-layer safety approach in Zwolle. It might be possible that responsibilities of Rijkswaterstaat and municipality related to Layer 3 are rather operational (when floods happen) than taken into account pro-actively and to reinforce the multi-layer safety approach.

Regarding territorial integration, both horizontal vertical integrations are noted in layer 1 which involve authorities working at the national level (Ministry and Rijkswaterstaat). This is not the case for the other layers. The water board Drents Overijsselse Delta plays a key role in territorial integration between layer 1 and layer 2 because it is the only water authority that cooperates with all the stakeholders of layer 2 (province and municipality) in both the Flood Protection Program and the IJssel-Vecht Delta Program. The lack of integration (neither vertical nor horizontal) of the water board Vallei en Veluwe with the other stakeholders raises some questions since they share the jurisdiction on the IJssel river in the city, and interventions made on one side of the river are interdependent with the ones made on the other side.

Another interesting aspect concerns both policy and territorial integration within the same layer. In layer 1 water authorities seem to support well the integration of water safety goals and regulations through collaboration across spatial scales and jurisdictional boundaries. The same happens for layer 2 between province and municipality. Integration between goals and regulations of layer 3 (disaster management) and its different authorities could not be determined based on this research. Probably, a greater number of respondents from the safety board of Overijssel would have clarified this aspect.

The two dimensions of integration (policy and territorial) provide a suitable analytical lens to understand processes between layers of the multi-layer safety approach and their state of integration. By identifying these two dimensions it was possible to understand multiple sides of integration and their relation. Policy integration can be neither comprehended nor obtained without territorial integration since the combination of regulation and goals between layers 1 and 2 is obtained through an effective collaboration between water and spatial planning authorities working among different jurisdictions and spatial scales. This suggests that there is an interdependence between policy and territorial integration in the multi-layer safety approach.

The integration of flood prevention policies into spatial planning policies could not be possible without the territorial integration between water board, province, and municipality.

Another interesting aspect concerns both policy and territorial integration within the same layer. In layer 1 water authorities seem to support well the integration of water safety goals and regulations through collaboration across spatial scales and jurisdictional boundaries. The same happens for layer 2 between province and municipality. Integration between goals and regulation of layer 3 (disaster management) and its different authorities cannot be well determined. Layer 3 is formed by multiple stakeholders (fire brigades, police officers, etc.), yet it is not clear if there is any integration between them.

The inclusion of water safety policies in new spatial developments (i.e. new neighbourhoods), the participation of the water board Drents Overijsselse Delta in spatial planning policies, and the fact that municipality and province changed building regulations in order to become ‘delta proof’, contribute to the knowledge about integration between water management and spatial planning in the multi-layer safety approach and more generally in flood risk management.

A greater contribution to the understanding of integration may be further researched within other integration dimensions such as institutional integration, and integration of different management systems. Also, it might be interesting how nature-based solutions, as one of the upcoming trends in flood risk management since some years (Schanze, Citation2017), influence the multi-layer safety approach. Nature-based solutions, namely, in essence require much more integrative approaches and stakeholder involvement (Hartmann et al., Citation2019). The embedment of water safety regulations into spatial planning (and not the other way around) extends what can be found in the literature, or rather that the role of layer 1 remains the more important for flood risk management, it cannot be substituted neither by spatial planning nor by disaster management in the multi-layer safety approach (Kaufmann et al., Citation2016; Pötz et al., Citation2014; Ritzema & Van Loon-Steensma, Citation2018).

This prominence of layer 1 raises the questions if and when layers 2 and 3 will gain more consideration in the future. On this matter, the results confirm that the Dutch flood risk management is affected by a strong tradition and successful experience in water safety measures (as argued by Jong & Brink, Citation2017), seen that the financial resources coming from the national government are mainly addressed to layer 1. In the long term however, the emphasis on layer 1 can result in unwanted effects, such as the dike paradox. In this case, investments in water protection measures can lead to increased vulnerabilities in the land these infrastructures are supposed to protect, since these lands are now considered to be safe and therefore can be developed (Tempels & Hartmann, Citation2014). Therefore, system failure and thus measures in the second and third layer are crucial. For example, this integration in the multi-layer safety approach might support the embracement of financial flood recovery schemes, necessary for an idea of resilient flood risk management (see Slavíková et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

This research illustrates aspects of integration between layers of the multi-layer safety approach within the delivery of the flood risk management plan for the city of Zwolle. This was done through the review of official documents and semi-structured interviews with stakeholders active in the three layers. This qualitative approach allowed us to gain in-depth knowledge about different types of integration taking place in the case study.

The results show that the water authorities and their safety measures are the main rulers in the multi-layer safety approach. However, integration is recognizable in policies that combined water safety with spatial planning measures through stakeholders’ cooperation. Zwolle represents a case where water safety policies, integrated into spatial adaptation, support the acceptance of water on the land to reduce all the components of flood risk (probability and consequences). Yet, according to the multi-layer safety approach, the decrease of consequences depends also on the integration of water safety into layer 3. As such, the integration remains uncompleted due to the general lack of a combination of disaster management measures (layer 3) with the other 2 layers. In other words, the integration of flood risk management into spatial planning takes place at the level of both policy integration and territorial integration. The empirical evidence of this research contributes to clarify how integration of water management into spatial planning can be obtained without conflicts of interest. However, the case study indicates that there is a need to investigate the integration of layer 3, where both dimensions of integration are lacking.

These results might be related to the fact that integration is not concretely defined or operationalized in the multi-layer safety approach. This could derive from the economic restrictions that adaptive flood risk management is subject to, since the financial sources of the multi-layer safety approach are mainly addressed to structural measures, and neglect those which are land-use related. This contribution did not question the claim why integration of the layers is beneficial. It just explored how the integration is realized in practice. However, for the multi-layer safety approach to become more effective in achieving the intended added benefits by combining measures from the three layers, it would be key to understand the effects these dimensions have on flood risk management outcomes and how they can be improved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Baan, P. J., & Klijn, F. (2004). Flood risk perception and implications for flood risk management in the Netherlands. International Journal of River Basin Management, 2(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2004.9635226

- Billé, R. (2008). Integrated coastal zone management: Four entrenched illusions. SAPIEN.S. Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, 1(2).

- Cumiskey, L., Priest, S. J., Klijn, F., & Juntti, M. (2019). A framework to assess integration in flood risk management: Implications for governance, policy, and practice. Ecology and Society, 24(4), 17. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11298-240417

- De Moel, H., van Vliet, M., & Aerts, J. C. (2014). Evaluating the effect of flood damage-reducing measures: A case study of the unembanked area of rotterdam, the Netherlands. Regional Environmental Change, 14(3), 895–908.

- Gersonius, B., Rijke, J., Ashley, R., Bloemen, P., Kelder, E., & Zevenbergen, C. (2016). Adaptive Delta management for flood risk and resilience in dordrecht, The Netherlands. Natural Hazards, 82(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-2015-0

- Hartmann, T., Slavíková, L., & McCarthy, S. (2019). Nature-based flood risk management on private land: Disciplinary perspectives on a multidisciplinary challenge. Springer.

- Hartmann, T., & Spit, T. J. M. (2016). Implementing the European flood risk management plan. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(2), 360–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2015.1012581

- Hornby, A. S., Cowie, A. P., Gimson, A. C., & Hornby, A. S. (1974). Oxford advanced learner's dictionary of current English (Vol. 1428). Oxford University Press.

- Hoss, F., Jonkman, S. N., & Maaskant, B. (2011). A comprehensive assessment of multilayered safety in flood risk management – the Dordrecht case study. In ICFM5 Secretariat at International Centre for Water Hazard Risk Management (ICHARM) and Public Works Research Institute (PWRI), Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Flood Management (ICFMS), Tokyo, Japan (pp. 57-65).

- Jong, P., & Brink, M. V. D. (2017). Between tradition and innovation: Developing flood risk management plans in the Netherlands. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 10(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12070

- Kaufmann, M., Mees, H., Liefferink, D., & Crabbé, A. (2016). A game of give and take: The introduction of multi-layer (water) safety in the Netherlands and flanders. Land Use Policy, 57, 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.033

- Kidd, S. (2007). Towards a framework of integration in spatial planning: An exploration from a health perspective. Planning Theory & Practice, 8(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350701324367

- Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. (2009). Beleidsnota waterveiligheid.

- Ministry of Public Transport and Water. (2009). Nationaal waterplan.

- Neuvel, J. M., & van den Brink, A. (2009). Flood risk management in Dutch local spatial planning practices. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 52(7), 865–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560903180909

- Neuvel, J. M. M., & Van Der Knaap, W. (2010). A spatial planning perspective for measures concerning flood risk management. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 26(2), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900621003655668

- Pötz, H., Anholts, T., & de Koning, M. (2014). Multi-level safety: Water resilient urban and building design. STOWA.

- Ran, J., & Nedovic-Budic, Z. (2016). Integrating spatial planning and flood risk management: A new conceptual framework for the spatially integrated policy infrastructure. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 57, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2016.01.008

- Ritzema, H. P., & Van Loon-Steensma, J. M. (2018). Coping with climate change in a densely populated delta: A paradigm shift in flood and water management in The Netherlands. Irrigation and Drainage, 67, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.2128

- Schanze, J. (2017). Nature-based solutions in flood risk management - buzzword or innovation? Journal of Flood Risk Management, 10(3), 281–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12318

- Scholten, T., Hartmann, T., & Spit, T. (2020). The spatial component of integrative water resources management: Differentiating integration of land and water governance. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 36(5), 800–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2019.1566055

- Slavíková, L., Hartmann, T., & Thaler, T. (2020). Financial schemes for resilient flood recovery of households. Environmental Hazards, 19(3), 223–227.

- Sutanta, H., Bishop, I. D. B., & Rajabifard, A. R. (2010). Integrating spatial planning and disaster risk reduction at the local level in the context of spatially enabled government. In Spatially enabling society research, emerging trends and critical assessment (1, pp. 55–68). Leuven University Press.

- Tempels, B., & Hartmann, T. (2014). A co-evolving frontier between land and water: Dilemmas of flexibility versus robustness in flood risk management. Water International, 39(6), 872–883. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.958797

- Van Buuren, A., Ellen, G. J., & Warner, J. (2016). Path-dependency and policy learning in the Dutch delta: Toward more resilient flood risk management in the Netherlands? Ecology and Society, 21(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08765-210443

- van den Brink, M., Termeer, C., & Meijerink, S. (2011). Are Dutch water safety institutions prepared for climate change? Journal of Water and Climate Change, 2(4), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2011.044

- van Herk, S., Zevenbergen, C., Gersonius, B., Waals, H., & Kelder, E. (2014). Process design and management for integrated flood risk management: Exploring the multi-layer safety approach for dordrecht, The netherlands. Journal of Water and Climate Change, 5(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2013.171

- Voskamp, I. M., & Van de Ven, F. H. M. (2015). Planning support system for climate adaptation: Composing effective sets of blue-green measures to reduce urban vulnerability to extreme weather events. Building and Environment, 83, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.07.018

- Woltjer, J., & Al, N. (2007). Integrating water management and spatial planning: Strategies based on the Dutch experience. Journal of the American Planning Association, 73(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360708976154

- Zandvoort, M., & van der Vlist, M. J. (2014). The multi-layer safety approach and geodesign: Exploring exposure and vulnerability to flooding. In D. J. Lee (Ed.), Geodesign by Integrating design and geospatial sciences (pp. 133–148). Springer.