ABSTRACT

Globally, demand for water resources is projected to increase due to climate change and population growth. In many developing contexts, water demand already far exceeds supply and alternatives are already required. Recycled water is increasingly seen as a source of alternative water supply to plug demand-supply gaps. This study examined the factors that influence recycled water acceptance amongst residents of Accra, Ghana. We found that irrespective of the technical specifications on water quality, consumers were only willing to use recycled water for some purposes due to low levels of trust in water service providers because of their inefficiencies and unreliable service provision. Cultural beliefs relating to human waste and the ingestion of waste underlines peoples’ acceptability of recycled water. Thus, future water reuse planning must include community engagement at the planning stage to create the level of trust needed for reuse acceptability.

1. Introduction

The global urban population is projected to increase to 6.3 billion by 2050, with about 73% of this increase occurring in developing economies (UN DESA Citation2015). In Africa, the urban population will increase from 350 million to 1.1 billion by 2050 (UN DESA Citation2015). However, urban growth in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has already resulted in informal settlements characterised by poor and inadequate housing without access to essential services, including water, electricity, healthcare, and road networks (UN Habitat Citation2016).

Urban authorities in SSA face the monumental challenge of providing the necessary infrastructure and services, including water, to keep pace with the rapid growth of cities. In the case of water, demand often exceeds available supplies, and water security is a primary concern for over 80% of the world’s population (Fielding, Dolnicar, and Schultz Citation2019). Globally, more than 150 million people already experience perennial water shortages across cities, a figure projected to reach one billion by 2050 (UN DESA Citation2018).

In SSA, efforts to bridge the demand-supply gap have yielded minimal results, with access to improved water sources across countries only increasing from 83% in 1990 to 87% in 2015 (UN DESA Citation2015). In urban areas, access to piped water at homes in SSA decreased from 43% in the 1990s to about 33% in 2015, mainly due to the rapid sprawling of cities coupled with essentially non-existent corresponding infrastructure development (Nganyanyuka et al. Citation2014). Thus, there are increased water insecurity levels in many urban communities, especially in low-income neighbourhoods (Nganyanyuka et al. Citation2014).

Urban water challenges continue to undermine the feasibility of meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN-SDGs) Goal 6 – to improve access to water and sanitation (UN Citation2015). Indeed, water crises rank among the top three global risks in terms of impact on societies (World Economic Forum Citation2017) and thus require innovative approaches to bridging the demand-supply gap.

In Ghana, rapid urbanisation has significantly impacted service and infrastructure provision (Owusu and Oteng-Ababio Citation2015). The rate of urbanisation increased from 36% in the 1990s to 55% in 2020. Ghana’s urbanisation rate is projected to reach 63.4% by 2030, with Accra expanding beyond its boundaries (Yiran et al. Citation2020). Only 24% of households in urban Ghana have access to pipe-borne water inside their dwelling, while about 26% of households have access to pipe-borne water outside of the residence (GSS Citation2014a). However, 1.4 million people in urban areas still lack access to drinking water services, and 6.7 million lack access to safely managed drinking water sources (Tetteh et al. Citation2022).

In Accra, Ghana’s capital, water demand far outstrips supply, with just about 36% of residents in the Accra Metropolitan Area (AMA) having access to piped water. Water is supplied by the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL) from the Kpong, Weija and Nswan Kwanyaku plants, with capacities of 451,000 m3, 244,000 m3 and 40,000 m3 /day, respectively. However, current and projected demand exceeds supply. Further, technological and financial constraints have already resulted in the shutting down of a desalination plant (Teshie Desalination Plant). This implies that unless alternative water sources are introduced, the demand-supply gap in Accra could increase, further reducing the population with access to clean water.

2. Water reuse

While most developing countries have emphasised increasing access to water, minimal attention is paid to managing wastewater as an end product (UN-Water. Citation2015). Many wastewaters are poorly managed and discharged into the ecosystem without proper treatment. Globally, only about 20% of the wastewater generated is treated (Drechsel, Qadir, and Wichelns Citation2015). The treatment and use of wastewater can increase water available for potable and non-potable use, reduce degradation of water ecosystems, and reduce exposure to contaminated water-related health burdens (Jhansi and Mishra Citation2013).

In Namibia, 35% of drinking water is treated wastewater, while in Singapore, 30% of all water comes from treated wastewater (Saad, Byrne, and Drechsel Citation2017). Water reuse is classified as indirect or direct reuse. Indirect reuse, which involves delivering treated wastewater into natural aquifers and later pumping it out, re-treating it before supplying it to consumers, already occurs in several cities worldwide (Dickin et al. Citation2016). On the other hand, direct reuse is a closed-loop system that involves treating wastewater to set standards and directly delivering it into the mains.

Comparatively, desalination, the process of removing dissolved salts and minerals from saline water to produce potable water is spite of its potential remains expensive in terms of cost and environmental implications (Green and Bell Citation2019). Thus, water recycling is lower in cost than desalination due to lower energy demand and fewer environmental impacts. However, public acceptance of recycled water remains a significant challenge due to such factors as disgust, perceptions of risk from the recycled water, and lack of trust in authorities (Etale et al. Citation2020; Hui, Ulibarri, and Cain Citation2020; Mankad and Tapsuwan Citation2011; Prins et al. Citation2022; Saad, Byrne, and Drechsel Citation2017).

Consumers express some level of emotional displeasure at the thought of using recycled water due to discomfiting psychological associations people have of wastewater. Garcia-Cuerva, Berglund, and Binder (Citation2016) defined the disgust factor as emotional distress generated by close contact with certain unpleasant stimuli. People’s expression of disgust for wastewater reuse stems from their perceived dirtiness and the fear that it might contain pathogens (Dolnicar and Hurlimann Citation2010). Recycled water has been linked with such labels as ‘toilet to tap’ and ”drinking sewage’ (Thorley Citation2006). Such negative emotional sentiments significantly influence people’s willingness to accept recycled water for potable use even after controlling for other factors such as risk perception, trust in institutions, and source of the recycled wastewater (Wester et al. Citation2016). Studies show that people with higher waste and uncleanness aversion (Fielding, Dolnicar, and Schultz Citation2019), stronger pathogenic disgust (Wester et al. Citation2015), and contagion sensibility have a reduced willingness to consume recycled water (Rozin et al. Citation2015). Importantly, however, Dobbie and Brown (Citation2014) note that the yuck factor mediates risk perception, and any analysis of disgust must be situated within a specific socio-cultural context. This implies that findings from one socio-cultural contexts may not be applicable in other contexts, hence the need for this study.

Recycled water is also perceived to present health risks due to the presence of residual pathogens in the water, despite treatment. Health is at the core of risk perception, which leads to lower acceptance of recycled water for potable and non-potable uses (Dolnicar, Hurlimann, and Nghiem Citation2010; Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2016). The number of persons worried about health concerns associated with recycled water ranges from as low as 5% to as high as 92% (Baghapour, Shooshtarian, and Djahed Citation2017; Buyukkamaci and Alkan Citation2013; Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2016). According to Jeffrey and Jefferson (Citation2003), people are more willing to use recycled water from their private bath/shower than their neighbours, hospitals, or motorway service stops. However, public health risk concerns about recycled water often run contrary to expert views (Hurlimann and Dolnicar Citation2016).

Because individual consumers lack the know-how, resources and technology to ascertain water quality, they must trust institutions to provide quality water (Ross, Fielding, and Louis Citation2014). According to Ross, Fielding, and Louis (Citation2014, 62), trust in the context of reuse acceptability is ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behaviour of the authority responsible for the recycled water scheme’. Thus, trust in institutions is dependent on experience/track record. Ross, Fielding, and Louis (Citation2014) identified fairness, identity, and credibility as the predictors of trust. Based on the view that people are more compliant with regulations if they believe they have been treated fairly, it is argued that fair procedures in reuse planning can improve acceptability.

In planning processes, fairness to community members indicates ‘whether and how much they share an identity with authorities. Shared social identity, in turn, increases the likelihood that group members trust authority and accept their decisions’ (Ross, Fielding, and Louis Citation2014, 62). People’s ability to identify with a particular project will improve their acceptability. In water reuse planning, proactive community engagement will create a sense of responsibility and community identity with the project, which is vital for acceptability. Linked to the issue of social identity is credibility, which is also a function of trust (Dobbie, Brown, and Farrelly Citation2016). When people identify with water service providers, they are more likely to perceive such institutions as competent in reuse planning. Trust between stakeholders can be achieved through collaborative, cross-disciplinary and inter-organisational platforms that enable and support communication and co-production of new knowledge through lateral knowledge transfer between all stakeholders (Dobbie, Brown, and Farrelly Citation2016).

In Ghana, extant literature on urban water has focused on access, cost, stability, and safety (Ablo and Yekple Citation2018; Asare Bediako et al. Citation2018; Dapaah and Harris Citation2017). These studies show that Accra suffers from an erratic water supply with high inequality in access to potable water. Many households in Accra are dependent on unsafe water sources for domestic use. This paper contributes to the growing literature by examining the potential for using recycled water to bridge the demand-supply gap in Accra.

First, we explore the acceptability of reclaimed water for various domestic purposes and identify the role of sociodemographic factors in acceptance. A second aim was to examine whether perceptions of health risks or cultural factors influenced residents’ acceptance of recycled water use in general and for particular uses. Finally, we examined the link between institutional trust and the acceptance of alternative water sources. Using data collected by mixed methods, we show that irrespective of the high-water demand and the purity of recycled water, consumer trust in water service providers is a key factor for acceptance of recycled water. We propose that public engagement in reuse planning will be crucial to achieving reuse acceptability.

3. Methods

3.1. Study area

The data collection was done in Accra between 2018 and 2020. The study sites are, Bubuashie, Korle Bu and Jamestown. Bubuashie is a middle-income community, Korle Bu is high-income and Jamestown, low-income in AMA. Bubuashie is a bustling commercial area with a population of 43,374 (GSS Citation2014b). The ethnic background of Bubuashie’s population is mixed. It has a mixture of commercial and residential use. Most commercial activities are found along the main roads in the area and mainly in retail activities. Other residents also ply their trade in the Kaneshie or Accra Central market, the two major commercial areas close to Bubuashie. Residential buildings are primarily multi-occupant and often interspersed with a few single-occupant family houses (detached or self-contained – which are houses with bathrooms, kitchen and toilet inside for the use by only those living in the unit). The community faces challenges with infrastructure and access to environmental services. Water and sanitation access is undoubtedly a challenge, and several people resort to water tankers for water supply.

Korle Bu hosts Ghana’s premier teaching hospital, medical laboratories and many healthcare professionals. Korle Bu is a mixed-use residential area with a total settlement population of 27,826 and commercial activities, including pharmaceutical stores, serving the Korle Bu Teaching hospital. Residential building includes bungalows that are either detached or semi-detached and serves as hospital staff’s residence. Also in the residential quarters are multi-occupant buildings occupied by low-echelon workers such as labourers and security guards.

Jamestown is an indigenous Ga fishing community located along the coast of Accra with a population of 44,613. It is one of the oldest residential communities in Accra, with a unique blend of colonial and indigenous cultures. The residential area has a mixture of commercial and residential use. Residents mainly depend on fishing and fishing-related activities, and the housing comprises predominantly multi-occupant family buildings that have been degraded due to low maintenance and high occupancy rate. The community face severe challenges with access to infrastructure and services, including water supply and sanitation (Arguello et al. Citation2013).

3.2. Data collection

The study used a mixed-method approach that entailed various research methods, including surveys, interviews, focus group discussion and participatory stakeholder engagement. Grounded in transdisciplinary approaches (see, Hansson and Polk Citation2018), the research identified and engaged stakeholders in the urban water sector at each stage of the research process. This approach aims to engender knowledge co-production in which researchers and research participants are active participants in the knowledge production process. To achieve this, we engaged stakeholders like the Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL), Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC), AMA, Sewerage Systems Ghana Limited, NGOs, and consumers to delineate Ghana’s urban water challenge.

In 2019, we proceeded first with a ‘silo’ engagement with identified stakeholders through surveys, interviews and three focus group discussions. By this, each stakeholder group is engaged separately to gain their views and experiences on the water situation in Accra and reuse acceptability. Key informants’ interviews were conducted, with specific topics being discussed with different stakeholders ). Fifty (50) residents from AMA were also interviewed on the water supply situation, the accessibility and cost challenges and water quality and reuse acceptability.

Table 1. Categories of respondents and issues discussed.

A total of two hundred and ninety-nine (299) questionnaires were administered, with 141 in Bubuashie, 86 in Korle Bu and 72 in James Town using size to ratio. The semi-structured questionnaire contained both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Thus, it allowed participants to reflect on the current water situation, knowledge of recycled water and factors that influence their perceptions of recycled water. The survey commenced with a transect walk through the communities to understand the communities’ general land use and layout. Respondents were randomly selected based on the number of houses counted along the street and commercial areas.

The survey data was analysed using SPSS with results presented in tables and graphs as well as chi-square test of the relationship between variables. The interview and focus group data were transcribed and manually analysed based on the themes that emerged regarding reuse acceptability. A stakeholder workshop was organised to create a platform for knowledge exchange and corroboration of data produced through interviews, surveys and focus group discussions. The stakeholder workshop brought together water users, service providers and officials of the assembly. The stakeholder workshop allowed the research team and research participants to deliberate on critical issues about wastewater reuse acceptability in Accra. The workshop commenced with a short survey on wastewater reuse acceptability, presentation of a summary of the survey findings to participants for feedback, and a discussion of the results.

Additionally, officials from GWCL, Sewerage Systems Ghana Limited, presented on water supply in Accra and wastewater treatment, respectively, followed by discussions by all participants. This workshop enabled participants to exchange ideas and confront misconceptions of water reuse.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The role of sociodemographic factors in reuse acceptability

Like many rapidly urbanising African cities, Accra faces severe water challenges as demand outstrips supply. While wastewater reuse is emerging as critical to bridging demand-supply gaps, there remain significant issues that must be addressed in reuse planning. Understanding the essential factors is key to the acceptability of integrating recycled water into the supply network.

Demographic factors play a critical role in the public acceptability of wastewater reuse projects. Most of the survey respondents were women (56.5%), with Jamestown having the highest female composition of 63.9% among the communities. This result is not surprising as it evinces the official records available for the region, indicating a 51.9% of the population is female (GSS Citation2010). Nonetheless, the highly skewed distribution favouring women in the case of Jamestown could be that they are primarily engaged in the home-based enterprise. Thus, women were available during the survey periods while most men may have left for fishing, their predominant occupation.

shows that most respondents who know about wastewater recyclability had secondary level education (45.7%), while a substantial proportion also had a tertiary level of education (23.4%). However, those who indicated that they are not aware about wastewater reuses have primary and secondary education, with just 23.4% having had tertiary level education. A chi-square test shows a significant relationship between education and awareness of wastewater recycling. Thus, in , we realise that there is a likelihood that the higher a person’s level of education, the more likely they may know about wastewater recycling.

Table 2. Level of education and wastewater recycling awareness.

Although there is a positive correlation between education and knowledge about recycled water, a chi-square analysis based on shows no significant relationship between the educational level of respondents and their willingness to use recycled wastewater. An official of a wastewater treatment plant noted, ‘Even as an engineer, I know that wastewater can be treated to WHO standards, but there is no way I will drink it’. Thus, even for people who are well educated, wastewater may not be acceptable for potable uses ().

Table 3. Educational level and willingness to use treated wastewater.

Most respondents who said they were willing to use treated wastewater had secondary level education as their highest level of education (41.1%). Similarly, most respondents who responded no (i.e. unwilling to use recycled wastewater) had secondary level education as their highest level of education.

In other words, the level of education of a person is not a likely factor that will influence their willingness to use recycled water. Even highly educated people who understand the safety and relevance of recycled water to augment water supply will not use it. One noted, ‘I will not use it myself as an expert, let alone recommend it to others’.

4.2. Health risk perception and acceptability of recycled water

In Accra, health risks concern regarding recycled water greatly influences acceptability. Despite the water treatment and quality assurance, many people still do not consider it safe enough for potable uses. Interviews with experts revealed that even though they understand the level of treatment water receives and quality standards, they are still unwilling to use recycled water for potable purposes. As a quality assurance officer noted, ‘I know the water is treated to safe standards. But I am still worried there may be some level of health risks when this water is consumed’. Hurlimann and Dolnicar (Citation2016) argued, the fundamental aspect of risk regarding water reuse is health. Thus, although the relevance of recycled water in plugging the supply deficit is undoubted, this paper and others show the health risk perception of people influences their view of recycled water (Hou et al. Citation2021; Kaercher, Po, and Nancarrow Citation2003; Po, Nancarrow, and Kaercher Citation2003). As will be discussed later, the lack of trust in Ghanaian institutions also heightens the health concerns. Conversely, in the United States, people accepted recycled water that has previously had little human contact, and when people did not link reclaimed water with wastewater (Mankad and Tapsuwan Citation2011).

Officials of the waste treatment company in Accra are adamant about supplying their water because ‘these people already have several health issues and sometimes drink unsafe water. Every year once it starts raining, there is cholera outbreaks. Imagine if we are supplying recycled water and there is any such outbreak, they will quickly blame us [the waste treatment company]. So, we will not put ourselves in such a position’. The view above confirms the argument by Jeffrey and Jefferson (Citation2003), Dolnicar and Schäfer (Citation2009) and Fielding, Dolnicar, and Schultz (Citation2019) that public health safety remains a significant concern regarding water recycling, particularly for potable purposes. Public health risks remain an important issue at the institutional level, hence the unwillingness to supply recycled water to urban households. Over the past decades, Accra has experienced perennial cholera outbreak related to faecal contamination of water and food (Thompson Citation2020) hence the unwillingness of authorities to supply reclaimed water in spite of its quality and safety.

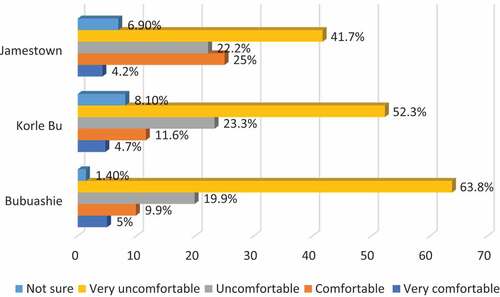

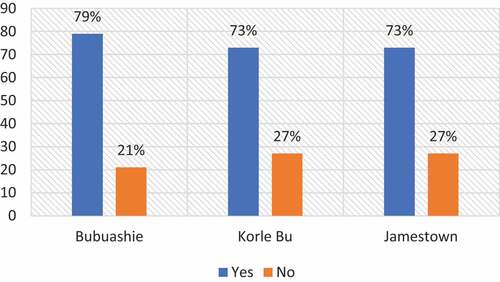

In Accra, health concerns regarding the potable use of recycled water are high, as shown in below. In all three study communities, over 70% of respondents expressed health risk concerns regarding the safety of recycled water for potable uses.

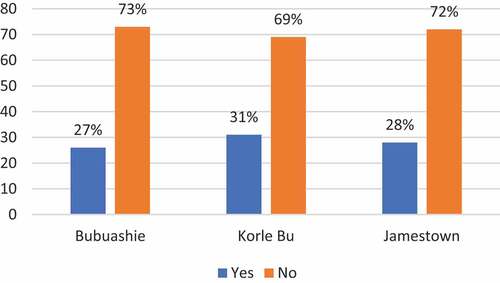

Conversely, when respondents were asked about health risks concerns regarding recycled water for non-potable uses, the acceptability for Bubuashie increased from 21% to 73% of respondents. In Korle Bu, it increased from 27% to 69%, and for Jamestown, the number of respondents with no health risk concerns increased from 27% to 72%. Thus, for respondents in Accra, health risk concerns for non-potable use of recycled water are low, as shown in below.

Field observation in Accra shows that the direct use of untreated wastewater for irrigation is already high. Across Accra, many vegetable farms located along major drainages use untreated wastewater for irrigation. Many youths produce cucumber, carrots, green pepper, cabbage, cauliflower, and spring onions for urban consumers (Antwi-Agyei et al. Citation2016). As a respondent argues, ‘when it comes to using wastewater for farming, we already do that, and people are fine with it’. Dickin et al. (Citation2016) show that wastewater in agriculture exposes farmers and consumers to various health risks. In Accra, water is pumped directly from the drains to irrigate crops without treatment. The farmers are exposed to pathogens and toxins in the contaminated water used for irrigation. Additionally, the risk of contamination of the vegetable supplied to consumers is high.

Regarding the consumption of vegetables produced with untreated water, the general view of respondents is that the water is not consumed directly; hence the potential for any health risks is low. Here, we argue that the central issue about direct potable use of recycled water and consumption of vegetables produced using untreated wastewater relates to disgust. Many respondents expressed disgust at the direct use of recycled water. As a 65-year-old participant said, ‘It is just disgusting and unimaginable for me to drink water that previously contained urine and toilet’. According to Wester et al. (Citation2016), negative emotions significantly influence public acceptance of recycled water. Regarding the potential health risks related to contamination of vegetables, respondents argue that once they wash the vegetables properly, they are sure it is safe to consume.

4.3. Culture and institutional trust in reuse planning

A critical factor in recycled water acceptability is culture and institutional trust (Fragkou and McEvoy Citation2016). Norms and values pertinent in any society influence people’s level of disgust. Disgust – an emotional expression demonstrated by the public about their discomfort in using wastewater is apparent in the case of Accra. Participants in the survey, focus group, interviews, and workshops express disgust at using recycled water. As one respondent notes, ‘No matter how clean the [recycled] water is, I do not see myself drinking my urine or water from the sewer’. These negative emotional sentiments significantly influence the public’s willingness to accept recycled wastewater for potable uses (Dolnicar, Hurlimann, and Grün Citation2011). They also represent what Gul et al. (Citation2021) viewed as contagion, where the association of water with sewer elicit a negative view irrespective of the water quality.

In Accra, disgust about wastewater is high, particularly from the individual surveys and interviews. During the interactive section, this disgust was confirmed by participants who expressed misgivings about using recycled water. But this disgust is culturally embedded, and as a participant noted, ‘it is culturally unacceptable for me to consume something that the body rejects’. The view here is that wastewater contains urine and faecal matter, which ‘the body rejected’; hence, potable use of recycled water relates to the re-ingestion of waste from the human body.

As a Works Engineer argued, ‘recycled water can be used for construction purposes but not potable use. Our culture does not permit us to use waste, let alone wastewater’. In effect, cultural beliefs about what is acceptable for human consumption significantly influence the acceptability of recycled water. The strong views of even experts who reject recycled water are critical because these are the officials who advise the government on investments to improve access to water in Ghana.

In addition to the cultural factors, trust (see above) plays a critical role in the acceptability of recycled water. Respondents contend that even the current water supplied by GWCL is sometimes contaminated; hence they do not trust them to recycle water for potable uses. According to a respondent, ‘even the water supplied by Ghana Water Company for drinking is not clean. There have been many occasions where the water coming from our tap is dirty. How can I trust them to treat wastewater clean enough for me?’ There is a general mistrust of the service provider in Accra to treat wastewater for potable use adequately. The feedback from respondents relates to instances where water supplied by GWCL occasionally is not clean.

Table 4. Trust in service providers.

GWCL explained that these situations occur when supply lines are damaged, or people illegally connect to the network. They take steps to flush the supply network and maintain a high-quality water supply. However, the general mistrust of Ghana’s water service provider and state institutions is a significant factor undermining recycled water acceptability. As many scholars have argued, trust in institutions is based on the relationship between consumers and institutions, credibility, and track records (Dolnicar and Hurlimann Citation2009; Friedler et al. Citation2006; Ross, Fielding, and Louis Citation2014). The experiences of Ghanaians regarding the supply of contaminated water by GWCL dents its integrity and people’s trust in the company to safely recycle water.

Some experts interviewed believed state agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, Water Resource Commission, and the Ministries, Department and Agencies with the power to monitor and protect consumers have failed to regulate effectively. Thus, there are low levels of trust in the GWCL and other state institutions. State institutions are often slow, ponderous, and unresponsive to the needs of the public. In effect, people do not have confidence in these institutions; hence, their opinions regarding recycled water use are negative. The lack of trust among institutions is not unique to Ghana. Dobbie, Brown, and Farrelly (Citation2016) observed that Australian urban water practitioners do not trust all stakeholders to manage risk associated with owing water systems.

Addressing the negative public perception, trust, and cultural issues requires dialogue among stakeholders in reuse planning (Wester et al. Citation2016). During the interactive workshop on reuse acceptability in Accra, two experts explained the recycling processes and the safety standards to participants. We observed that many respondents who were previously unwilling to use recycled water were more receptive after understanding the recycling process. As Woody and Tolin (Citation2002) and Fu and Liu (Citation2017) observed, education and public engagement should be core to any reuse planning. However, short-term public forums where experts inform users cannot pass proper public engagement regarding reuse planning. A transdisciplinary approach (Hansson and Polk Citation2018) that aims at knowledge co-production in an egalitarian manner must be the gold standard for designing, planning, and executing reuse projects.

5. Conclusion

Climate change, rapid urbanisation, industrial growth, and agricultural demands have placed access to water at the centre of global debates on sustainable development. Globally, there is an increased demand for water resources as water has become a source of political contestation as societies struggle to access water. As water demand already far exceeds supply in many developing countries, there is increasing scholarly and policy attention towards alternative water sources.

Recycled water is increasingly seen as a source of alternative water supply to plug demand-supply gaps. This paper explored public perception about and acceptability of recycled water for various uses in Ghana. Irrespective of the technical specification, costs and state investments in recycled water, public support remains fundamental to any efforts at integrating reclaimed water into the supply system. It is suggested that institutional trust and cultural factors influence recycled water acceptance. There is a general lack of confidence in water service providers because of their inefficiencies and unreliable service provision.

Cultural beliefs relating to how people should interact with human waste and the ingestion of waste underlines peoples’ acceptability of recycled water. Even when wastewater is treated to global safety standards, these cultural factors greatly influence people’s perception and acceptance. The study shows that while untreated wastewater is used to irrigate vegetables consumed in Accra, consumers are more concerned about the direct potable use of recycled water. We surmise that trust-building interventions and the active participation of consumers in reuse planning may be critical to accepting recycled water. Thus, future water reuse planning must include community engagement at the planning stage to create the level of trust needed for reuse acceptability.

Ethics approval

The authors declare that there are no ethical conflicts associated with the submitted manuscript. The ethical clearance certificate for the project is R14/49 (Human Research Ethics Committee (non-medical).

Consent to participate

All authors have been allowed by their affiliation organisations to collaborate to this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of Korle Bu, Bubuashie and James Town for their participation in consultative workshops.

The corresponding author also acknowledges the BECHS-Africa project funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the fellowship at the Washington University in St Louis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ablo, A. D., and E. E. Yekple. 2018. “Urban Water Stress and Poor Sanitation in Ghana: Perception and Experiences of Residents in the Ashaiman Municipality.” GeoJournal 83 (3): 583–594. doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9787-6.

- Antwi-Agyei, P., A. Peasey, A. Biran, J. Bruce, J. Ensink, and F. Mertens. 2016. “Risk Perceptions of Wastewater Use for Urban Agriculture in Accra, Ghana.” PloS one 11 (3): e0150603. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150603.

- Arguello, J. E. M., R. Grant, M. Oteng-Ababio, and B. M. Ayele. 2013. “Downgrading–An Overlooked Reality in African Cities: Reflections from an Indigenous Neighborhood of Accra, Ghana.” Applied Geography 36: 23–30. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.04.012.

- Asare Bediako, I., X. Zhao, B. C. Ampimah, K. B. Boamah, and S. O. Mensah. 2018. “Exogenous Pressures and Probabilistic Assessment of Risk and Vulnerability of Urban Water Systems in Ghana.” Urban Water Journal 15 (6): 609–614. doi:10.1080/1573062X.2018.1529188.

- Baghapour, M. A., M. R. Shooshtarian, and B. Djahed. 2017. “A Survey of Attitudes and Acceptance of Wastewater Reuse in Iran: Shiraz City as A Case Study.” Journal of Water Reuse and Desalination 7 (4): 511–519. doi:10.2166/wrd.2016.117.

- Buyukkamaci, N., and H. S. Alkan. 2013. “Public Acceptance Potential for Reuse Applications in Turkey.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 80: 32–35. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.08.001.

- Dapaah, E. K., and L. M. Harris. 2017. “Framing Community Entitlements to Water in Accra, Ghana: A Complex Reality.” Geoforum 82: 26–39. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.011.

- Dickin, S. K., C. J. Schuster-Wallace, M. Qadir, and K. Pizzacalla. 2016. “A Review of Health Risks and Pathways for Exposure to Wastewater Use in Agriculture.” Environmental Health Perspectives 124 (7): 900–909. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509995.

- Dobbie, M. F., and R. R. Brown. 2014. “A Framework for Understanding Risk Perception, Explored from the Perspective of the Water Practitioner.” Risk Analysis 34 (2): 294–308. doi:10.1111/risa.12100.

- Dobbie, M. F., R. R. Brown, and M. A. Farrelly. 2016. “Risk Governance in the Water Sensitive City: Practitioner Perspectives on Ownership, Management and Trust.” Environmental Science & Policy 55: 218–227. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2015.10.008.

- Dolnicar, S., and A. Hurlimann. 2009. “Drinking Water from Alternative Water Sources: Differences in Beliefs, Social Norms and Factors of Perceived Behavioural Control across Eight Australian Locations.” Water Science and Technology 60 (6): 1433–1444. doi:10.2166/wst.2009.325.

- Dolnicar, S., and A. Hurlimann. 2010. “Desalinated versus Recycled Water: What Does the Public Think?” Sustainability Science and Engineering 2: 375–388.

- Dolnicar, S., A. Hurlimann, and B. Grün. 2011. “What Affects Public Acceptance of Recycled and Desalinated Water?” Water Research 45 (2): 933–943. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.09.030.

- Dolnicar, S., A. Hurlimann, and L. D. Nghiem. 2010. “The Effect of Information on Public acceptance–the Case of Water from Alternative Sources.” Journal of Environmental Management 91 (6): 1288–1293. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.02.003.

- Dolnicar, S., and A. I. Schäfer. 2009. “Desalinated versus Recycled Water: Public Perceptions and Profiles of the Accepters.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (2): 888–900. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.02.003.

- Drechsel, P., M. Qadir, and D. Wichelns. 2015. Wastewater: Economic Asset in an Urbanizing World. The Netherlands: Springer.

- Etale, A., K. Fielding, A. I. Schäfer, and M. Siegrist. 2020. “Recycled and Desalinated Water: Consumers’ Associations, and the Influence of Affect and Disgust on Willingness to Use.” Journal of Environmental Management 261: 110217. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110217.

- Fielding, K. S., S. Dolnicar, and T. Schultz. 2019. “Public Acceptance of Recycled Water.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 35 (4): 551–586. doi:10.1080/07900627.2017.1419125.

- Fragkou, M. C., and J. McEvoy. 2016. “Trust Matters: Why Augmenting Water Supplies via Desalination May Not Overcome Perceptual Water Scarcity.” Desalination 397: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2016.06.007.

- Friedler, E., O. Lahav, H. Jizhaki, and T. Lahav. 2006. “Study of Urban Population Attitudes Towards Various Wastewater Reuse Options: Israel as a Case Study.” Journal of Environmental Management 81 (4): 360–370. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.11.013.

- Fu, H., and X. Liu. 2017. “A Study on the Impact of Environmental Education on Individuals’ Behaviors Concerning Recycled Water Reuse.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 13 (10): 6715–6724. doi:10.12973/ejmste/78192.

- Garcia-Cuerva, L., E. Z. Berglund, and A. R. Binder. 2016. “Public Perceptions of Water Shortages, Conservation Behaviors, and Support for Water Reuse in the US.” Resources, Conservation And Recycling 113: 106–115. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.06.006.

- Green, A., and S. Bell. 2019. “Neo-hydraulic Water Management: An International Comparison of Idle Desalination Plants.” Urban Water Journal 16 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1080/1573062X.2019.1637003.

- GSS. 2010. Population by Region, District, Age Groups and Sex, 2010. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/pop_stats.html.

- GSS. 2014a. 2010 Population and Housing Census Report: Urbanisation. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- GSS. 2014b. 2010 Population and Housing Census: District Analytical Report, Accra Metropolitan. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service Retrieved from. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/pop_stats.html.

- Gul, S., K. Gani, I. Govender, and F. Bux. 2021. “Reclaimed Wastewater as an Ally to Global Freshwater Sources: A PESTEL Evaluation of the Barriers.” AQUA—Water Infrastructure, Ecosystems and Society 70 (2): 123–137.

- Hansson, S., and M. Polk. 2018. “Assessing the Impact of Transdisciplinary Research: The Usefulness of Relevance, Credibility, and Legitimacy for Understanding the Link between Process and Impact.” Research Evaluation 27 (2): 132–144. doi:10.1093/reseval/rvy004.

- Hou, C., Y. Wen, X. Liu, and M. Dong. 2021. “Impacts of Regional Water Shortage Information Disclosure on Public Acceptance of Recycled water—evidences from China’s Urban Residents.” Journal of Cleaner Production 278: 123965. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123965.

- Hui, I., N. Ulibarri, and B. Cain. 2020. “Patterns of Participation and Representation in a Regional Water Collaboration.” Policy Studies Journal 48 (3): 754–781. doi:10.1111/psj.12266.

- Hurlimann, A., and S. Dolnicar. 2016. “Public Acceptance and Perceptions of Alternative Water Sources: A Comparative Study in Nine Locations.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 32 (4): 650–673. doi:10.1080/07900627.2016.1143350.

- Jeffrey, P., and B. Jefferson. 2003. “Public Receptivity regarding “in-house” Water Recycling: Results from a UK Survey.” Water Science and Technology: Water Supply 3 (3): 109–116.

- Jhansi, S. C., and S. K. Mishra. 2013. “Wastewater Treatment and Reuse: Sustainability Options.” Consilience 10: 1–15.

- Kaercher, J., M. Po, and B. Nancarrow. 2003. Water Recycling, Community Discussion Meeting I. The Key Findings. Canberra: Australian Research Centre for Water in Society (ARCWIS). doi:10.2.100.100/193357?index=1.

- Mankad, A., and S. Tapsuwan. 2011. “Review of socio-economic Drivers of Community Acceptance and Adoption of Decentralised Water Systems.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (3): 380–391. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.10.037.

- Nganyanyuka, K., J. Martinez, A. Wesselink, J. H. Lungo, and Y. Georgiadou. 2014. “Accessing Water Services in Dar Es Salaam: Are We Counting What Counts?” Habitat International 44: 358–366. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.07.003.

- Owusu, G., and M. Oteng-Ababio. 2015. “Moving Unruly Contemporary Urbanism toward Sustainable Urban Development in Ghana by 2030.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (3): 311–327. doi:10.1177/0002764214550302.

- Po, M., B. E. Nancarrow, and J. D. Kaercher. 2003. Literature Review of Factors Influencing Public Perceptions of Water Reuse. 54/03. Citeseer: CSRIO.

- Prins, F. X., A. Etale, A. D. Ablo, and A. Thatcher. 2022. “Water Scarcity and Alternative Water Sources in South Africa: Can Information Provision Shift Perceptions?” Urban Water Journal 1–12. doi:10.1080/1573062X.2022.2026984.

- Ross, V., K. S. Fielding, and W. R. Louis. 2014. “Social Trust, Risk Perceptions and Public Acceptance of Recycled Water: Testing a social-psychological Model.” Journal of Environmental Management 137: 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.039.

- Rozin, P., B. Haddad, C. Nemeroff, and P. Slovic. 2015. “Psychological Aspects of the Rejection of Recycled Water: Contamination, Purification and Disgust.“ Judgment and Decision Making 10 (1): 50–63.

- Saad, D., D. Byrne, and P. Drechsel. 2017. “Social Perspectives on the Effective Management of Wastewater.” Physico-Chemical Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery 253.

- Tetteh, J. D., M. R. Templeton, A. Cavanaugh, H. Bixby, G. Owusu, S. M. Yidana, S. Moulds, B. Robinson, J. Baumgartner, and S. K. Annim. 2022. “Spatial Heterogeneity in Drinking Water Sources in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA), Ghana.” Population and Environment 1–31.

- Thompson, E. E. 2020. “Risk Communication in a Double Public Health Crisis: The Case of Ebola and Cholera in Ghana.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7–8): 962–977. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1819386.

- Thorley, D. 2006. “Toowoomba Recycled Water Poll.” Reform 89: 49–51.

- UN. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- UN DESA. 2015. “World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision.” In United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division, 41. New York, NY: USA.

- UN DESA. 2018. Revision of World Urbanization Prospects. New York: Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- UN Habitat. 2016. World Cities Report 2016: Urbanization and Development–Emerging Futures. New York: UN-Habitat.

- UN-Water. 2015. Wastewater Management: A UN-Water Analytical Brief. New York: UN.

- Wester, J., K. R. Timpano, D. Çek, and K. Broad. 2016. “The Psychology of Recycled Water: Factors Predicting Disgust and Willingness to Use.” Water Resources Research 52 (4): 3212–3226. doi:10.1002/2015WR018340.

- Wester, J., K. R. Timpano, D. Çek, D. Lieberman, S. C. Fieldstone, and K. Broad. 2015. “Psychological and Social Factors Associated with Wastewater Reuse Emotional Discomfort.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 42: 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.01.003.

- Woody, S. R., and D. F. Tolin. 2002. “The Relationship between Disgust Sensitivity and Avoidant Behavior:: Studies of Clinical and Nonclinical Samples.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 16 (5): 543–559. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00173-1.

- World Economic Forum. 2017. The Global Risks Report 2017, 12. Geneva: WEF. Insight Report, Issue.

- Yiran, G. A. B., A. D. Ablo, F. E. Asem, and G. Owusu. 2020. “Urban Sprawl in sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Literature in Selected Countries.” Ghana Journal of Geography 12 (1): 1–28. doi:10.4314/gjg.v12i1.1.