?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Atmospheric aerosols have been a subject to scientific interest at least since the Age of Enlightenment, including theories concerning the origins of atmospheric haze and dust. Early studies associated haze with geological sources – earthquakes and volcanism – which were believed to be related to the chemistry of sulphuric compounds. Thus, sulphuric acid became the strongest candidate to explain atmospheric new particle formation. The idea was carried over when the first quantitative studies of condensation nuclei and atmospheric chemistry took place during the later part of the 19th century. Laboratory and field measurements by von Helmholtz, Aitken, Kiessling, and Barus, among others, a century ago led to the conclusion that widespread new particle formation occurs in the atmosphere and is caused by sulphuric acid together with water and ammonia – a viewpoint, which has been rediscovered and expanded during the past 25 years.

1. Introduction

Humankind has been aware of atmospheric aerosol particles throughout its existence via common phenomena like dust and smoke, and consequently, the properties of atmospheric fine particles had captured the scientific interest during the classical period, as vividly demonstrated, e.g. by the description of the Brownian motion of illuminated dust particles in Lucretius’ De rerum natura (Lucretius, trans. Citation1916, II.112–141). It is therefore not surprising that over one and a half millennia later, the existence and effects of atmospheric aerosols were well known by Renaissance-era scientists: for example, the effect of atmospheric particles on the resolving power of telescopes was discussed by Auzout (Citation1666) in a letter to Abbé Charles only 56 years after the publication of Sidereus nuncius! However, sources of these particles and their formation mechanisms remained unclear – with some obvious counterexamples, such as smoke and coarse, windblown dust – although various hypotheses emerged during 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries (Husar, Citation2000; Mohnen and Hidy, Citation2010; Demarée, Citation2014).

More recently, sulphuric acid has been identified as the key component for new particle formation (NPF) in the atmosphere (Zhang et al., Citation2012; Kulmala et al., Citation2014), together with atmospheric bases such as ammonia and amines, and possibly some highly oxidized organic compounds (Elm et al., Citation2017). In coastal areas, methanesulphonic acid and iodine oxides may also play a dominating role. Correlation between atmospheric sulphuric acid concentration and NPF has led to considerations of significant climate feedback mechanisms (Charlson et al., Citation1987). It has also given rise to the routinely applied, though unjustified, analysis of the observed new particle formation rate as a function of sulphuric acid concentration to obtain the molecularity of the rate-limiting nucleation step (Marvin and Reiss, Citation1978; Weber et al., Citation1996; Kupiainen-Määttä et al., Citation2014). In fact, the connection between sulphuric acid and NPF seems so strong that its origins have apparently never come under scrutiny: it was identified in the studies of the causes of Los Angeles smog (Prager et al., Citation1960; Renzetti and Doyle, Citation1960), while others (Kulmala et al., Citation2004) have pointed out the pioneering measurements of Aitken (Citation1900). It turns out, however, that the connection between atmospheric haze events and sulphuric acid was already discussed in scientific literature much earlier. This discussion has intertwined the origin of secondary atmospheric particles, chemical transformation in the atmosphere, and the very nature of haze, vapor and particulates.

2. First scientific ideas: a tale of two disasters

In the wake of the Lisbon 1755 earthquake, several hypotheses on the causes of earthquakes were put forward. A prominent one was due to Immanuel Kant, who wrote a series of essays on the topic.1 Following Lémery (Citation1703), he considered exothermic underground reactions of sulphates and water (forming sulphuric acid) and iron minerals being the driving force behind tectonic and volcanic action. Although this line of reasoning failed, in two essays, Kant also made a connection between the formation of haze and release of vapors resulting from the above mentioned reactions and those including saltpeter (and thus producing nitric acid) from the ground: In the first essay (Kant, Citation1756a), he pointed out that the speculated reactions could lead to emanations of such vapors and produce visible haze. In the second essay (Kant, Citation1756b, p. 5–8), he made a connection between a haze event observed in Locarno, Switzerland on October 14 – two weeks before the Lisbon earthquake – and the assumed emissions of fumes from the reactions of sulphur-containing compounds; Husar (Citation2000) has proposed that the observed haze event could actually have been a Saharan dust episode. These essays made Kant the first to propose the connection between sulphuric acid and atmospheric NPF, although the idea of earthquakes preceded by atmospheric phenomena was already discussed by (Aristotle, trans. Citation1931, II.8) and paraphrased by Plinius (ed. Citation1906, II. 84). They wrote on the appearance of stretched clouds at the horizon before the earthquake, crediting Democritus for these observations. The appearance of such clouds was connected to the prevailing theory that earthquakes were due to shrinkage/expansion of soil with changes of its moisture. Kant must have been aware of these (and other early) theories of earthquakes (Oeser, Citation1992). Indeed, such explanations for earthquakes were still common during the 18th century, accompanied by biblical imagery of fire and brimstone, and there were several reports on sulphuric fumes connected to the Lisbon 1755 earthquake, which Demarée et al. (Citation2007) have explained as remains of the plume from the eruption of Katla in Iceland a fortnight before. Kant later started to doubt his own theory, as there might not be enough sulphur available in the Earth’s crust to explain the amount of released energy (Kant, Citation1802, p. 51). Interestingly, a particle formation mechanism, similar to the one originally described by Kant, although a less violent one, has been recently observed in nature (Cao et al., Citation2015).

Followed by the eruption of another Icelandic volcano, Laki, starting 8 June 1783, widespread and persistent haze covered most of Europe from late June until the end of autumn (Stothers, Citation1996; Thordarson and Self, Citation2003). The haze, caused by approximately 122 Gg of SO2 emitted into the atmosphere, affected weather patterns in the Northern Hemisphere, resulting in a persistent heat wave over western and northern Europe during the summer of 1783, while simultaneously colder than usual weather was observed in eastern Europe, northern Asia, and North America. The following winter was exceptionally cold on the whole Northern Hemisphere, which Thordarson and Self (Citation2003) attribute to the negative radiative forcing due to sulphuric acid aerosol. The persistent haze led to a number of published observations together with theoretical speculations concerning its origins. The haze was associated with an earthquake that struck Calabria in February 1783 associated with it (Toaldo, Citation1785), while some authors (Soulavie, Citation1783) considered other emissions from soil as the primary source of haze particles.2 Apparently, Mourgue de Montredon (Citation1784) in his address to the French Royal Academy of Sciences was the first researcher in continental Europe to abandon theories based on earthquake or soil emissions as the origin of the haze, instead linking its origins with the eruption of Laki, although the earthquake theory was considered valid well into the 19th century (Prout, Citation1834, p. 348).

Several observers noted a distinct sulphuric smell in connection to the 1783 haze, not only in Iceland (Thordarson and Self, Citation2003), but also across Europe, as documented by Senebier (Citation1784), Hólm (Citation1784, p. 8) Toaldo (Citation1785), and van Swinden (1785), who also reported on bleaching and plant injuries caused by acidic deposition. Also notable are descriptions concerning the distinctive dryness accompanying the haze (van Swinden, Citation1785): For example in Żagań, Preus (Citation1785) remarked concerning observations of June 17 that a very dry haze, as the fumes had adsorbed all moisture from the air, appeared and lasted until November. These observations are again to be compared with the known properties of sulphuric acid, or oil of vitriol in the 18th century parlance, available from earlier studies of alchemy and metallurgy (Karpenko and Norris, Citation2002).

Abundant concentrations of atmospheric particles not related to catastrophic events were also observed in central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. In a region occupying most of the area between North and Baltic Seas and Alps, forest fires and peat burning caused a phenomenon known as höhenrauch, heerraauch, moorrauch, solrök, or moorbrennen (Husar, Citation2000). This phenomenon was so common that Preus (Citation1785) commented that the first appearance of a dry fog in the summer of 1783 as being a similar occurrence. Various theories and observations related to höhenrauch have recently been reviewed by Demarée (Citation2014); despite being historically interesting for understanding processes related to aerosol formation and transformation from biomass burning, these mostly overlap with those proposed to explain the summer of 1783 dry haze or have little to do with the current reasoning concerning atmospheric NPF. An example of this later type of theory is an explanation of the observed haze as meteoritic dust.

3. On the role of atmospheric chemistry

Neither Kant, Marcorelle, nor their contemporaries made any clear distinction between primary and secondary particles. Indeed, even the concept of vapor was still vague until the mid-19th century (cf. Knowles Middleton, Citation1964), when the kinetic theory of heat finally superseded the caloric one, though the transformation was gradual and the nature of intermolecular forces remained elusive, as can be seen, e.g. from the description of gases and vapors given by (Prout, Citation1834, p. 56–64). However, Virey (Citation1803) has already speculated that combination of ‘various species of air’ could lead to formation of ‘corpuscles’ in the atmosphere. Patrin (Citation1809) proposed in a more direct manner that some part of atmospheric dust is formed from chemical reaction products of atmospheric gases, as obvious from the following citation (emphasis as in original):3

C’est d’après cette manière d’envisager les opérations de la nature, que j’ai surtout essayé d’expliquer a formation des matières volcaniques, par la combinaison chimique des fluides gazeux qui circulent dans le sein de la terre, et qui par l’effet de l’ASSIMILATION MINÉRALE, deviennent des corps pierreux et métalliques, analogues à ceux qu’on suppose formés par ce qu’on appelle la voie humide (1).

Or, cette théorie s’applique si naturellement à la formation des pierres météoriques, que je n’hésitai pas un instant à la regarder comme parfaitement identique avec la formation des matières que vomissent les volcans, c’est à dire par une combinaison chimique de divers fluides aériformes.

Obviously, Patrin considered the formation of secondary particles in the atmosphere to be an analogous process to the formation of volcanic emissions, which source he thought to lay in underground gaseous chemistry. Rafinesque (Citation1819) noted that sun rays are visible in the air even after rain, which supposedly had washed out most of the particles and following Virey and Patrin pointed out that there must be a chemical source of new particles in the atmosphere.

Although the exact nature of precursor species and their reactions in the air were still unknown – ozone together with its reactivity was to be discovered a couple of decades later (Schönbein, 1840; Rubin, Citation2001), and the role of hydroxyl radical in atmospheric chemistry was not completely recognized until the 1970s (Warneck, Citation1974; Wang et al., Citation1975) – in a subsequent letter Rafinesque (Citation1821) made a detailed statement on the chemical reactions responsible for atmospheric NPF that already sounds quite modern:4

The insight given us by modern chemistry into the gaseous formations of solid substances, will be amply sufficient to account for this spontaneous formation. We know that…sulfur, muriate of ammoniae, & c. can be formed by sublimation of gases…& c. may be spontaneously combined by a casual meeting or mixture of gaseous emanations. It is not therefore difficult to conceive how dusty particles may be formed in the great chemical laboratory of our atmosphere.

4. From natural philosophy to experimental science

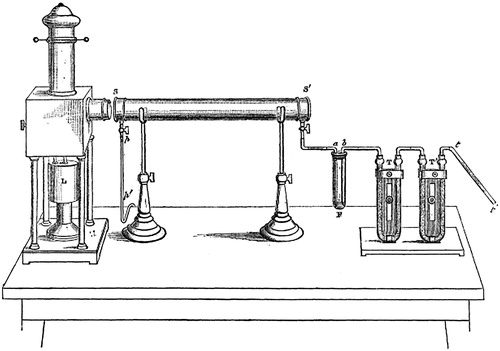

Most of the research concerning atmospheric aerosols until 20th century could be classified as belonging to natural philosophy, as it was based mostly on conclusions drawn from unsystematic observations (Husar, Citation2000). The first systematic and controlled studies on the formation and growth of aerosol particles were undertaken by John Tyndall. In 1868, he reported results from a series of experiments (Tyndall, Citation1868), where vapors of volatile liquids were exposed to light in a glass tube, forming clouds inside (). Varying the carrier gas from purified air to oxygen and hydrogen, he further showed that the observed reactions were due to photolytic decomposition of vapor molecules, not by oxidation. Yet, the selection of substances he used has some intriguing implications when considering the current knowledge of atmospheric NPF: nitrite of amyl, allyl, and isopropyl iodides, and hydrobromic, -chloric, and -iodic acids. In a subsequent paper (Tyndall, Citation1870), results of further experiments with various mixtures of organic compounds and CS2 with nitric acid were reported. Tyndall noted that minute impurities had a strong effect on the observed particle formation, and without thorough cleaning, trace amounts of vapors emanating from the glassware and metallic parts of the experimental setup were enough to produce a visible cloud of particles in an otherwise pure air. As Tyndall passed filtered air through sulphuric acid and potassium oxide, in this order, to dry it before admitting it into the glass tube, there is some possibility of sulphuric acid contamination of the glassware used in the experiments. One can say that these experiments mark the beginning of both photochemistry and aerosol research as scientific disciplines. Tyndall (Citation1881, footnote at p. 72) in fact gave the first proper definition of an aerosol (particle):

With regard to size, there is probably no sharp line between molecules and particles; the one gradually shades into the other. But the distinction that I draw is this: the atom or the molecule, if free, is always part of a gas, the particle is never so. A particle is a bit of liquid or solid matter, formed by the aggregation of atoms or molecules.

Fig. 1. The experimental setup used by Tyndall: Light source L is used to illuminate glass tube , into which air is bubbled through the studied liquid in flask F next to two U-tubes located at the right end of the table,

and T, containing fragments of glass coated with aqueous sulphuric acid and fragments of marble wetted with caustic potash, respectively, through which the air was admitted. Reproduced from Tyndall (Citation1870).

This statement also implies the existence of a barrier – kinetic or thermodynamic – for NPF. Although Tyndall was not using the term (chemical) potential here, he apparently had been on Gibbs’ mailing list—or had otherwise acquired a copy of Gibbs (Citation1875) article,5 and consequently was aware of his work on phase equilibrium. Along with Thomson’s (Citation1871) theoretical treatment on the equilibrium of small droplets within vapor, these works gave the firm theoretical basis for further studies in NPF and atmospheric condensation phenomena – and provided some information on the true sizes of freshly formed particles, although the first quantitative expression for the nucleation rate was given by Volmer and Weber (Citation1926), with a detailed kinetics for nucleation from vapor by Farkas (Citation1927).

Following the demonstration of Coulier (Citation1875) that there is something in unfiltered air in contrast to filtered air allowing water to condense at moderate supersaturations, other researchers became interested in the condensation of water vapor, using adiabatic expansion and cooling as the method to achieve supersaturation: simultaneously to Coulier, Aitken (Citation1881) had developed an expansion chamber of his own to study cloud condensation. Kiessling’s (Citation1884) motivation to build his expansion chamber was to replicate and study the optical effects created by the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, while von Helmholtz (Citation1886) performed the first studies with nozzles. All of them observed that when sulphuric acid was added to the expanding gas, condensation was strongly enhanced. Aitken and von Helmholtz, however, reached opposite conclusions on the relative strengths of sulphuric and hydrochloric acid enhancements: Aitken found hydrochloric acid being less effective, while von Helmholtz listed the relative effect of various acidic compounds as HCl > H2SO4 > SO2 > HNO3 > CO2. All three authors considered the formation of ammonium chloride as the reason for the observed effects with HCl, but only Aitken paid special attention to the reaction of sulphuric acid and ammonia in air. He further noted that these reactions can actually result in condensation without external nucleus, i.e. via homogeneous nucleation.

The role of ions in condensation was first demonstrated by von Helmoltz (Citation1887), and by the end of the 19th century, the nature of electric charge was a hot topic in science, and consequently ion-induced nucleation soon became the dominating topic of nucleation studies (Schröder and Wiederkehr, Citation1998). The possibility of homogeneous nucleation in the condensation of a non-reacting vapor was first proposed by Barus (Citation1893) on the basis of his own work on condensation of steam; von Helmholtz (Citation1886) had already earlier reached similar conclusions based on the Kelvin equation. The apex of the 19th century development concerning these topics was the development of the cloud chamber by Wilson (Citation1897), who not only quantified the effect of ions on the critical supersaturation required to form droplets, but also demonstrated the chemistry-mediated effect of UV radiation on NPF, and also performed the first controlled experiments on the homogeneous nucleation of water vapor, confirming the conclusions of von Helmholtz and Barus, which also lead to the quantification of the size range of freshly formed particles, separating NPF and atmospheric haze formation as distinct, but related processes.

The first atmospheric observations of new particle formation are due to Aitken (Citation1900), who later (Aitken, Citation1913) proposed that atmospheric NPF essentially follows from photolytic reactions (referring to Tyndall’s work here), leading to gas-phase oxidation of SO2 to H2SO4, which then together with ammonia and water vapor forms new particles – the effect of electrochemical formation of ozone and subsequent enhancement of condensation due to inorganic acid build-up was already demonstrated by von Helmholtz and Richarz (Citation1890). The first continuous measurements, reporting longer times related to atmospheric NPF were, however, obtained on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

5. Carl Barus: one of the 9996

On the contrary to his Scottish and German contemporaries and corrivals (cf. Podzimek, Citation1989; Schröder and Wiederkehr, Citation2000; Harrison, Citation2011), Carl Barus’ contributions to atmospheric sciences have largely fallen into oblivion despite some of his pioneering studies related to vapor-to-liquid nucleation and atmospheric NPF.7

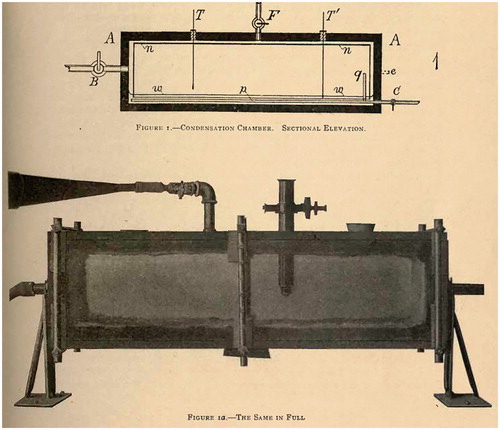

Barus was the first one to report long time series on variation of the concentration of atmospheric particles from both urban (Providence) and remote (Block Island) environments together with meteorological parameters, at first using ad hoc instrumentation (Barus, Citation1902, Citation1903), and later a fog chamber of his own design () (Barus, Citation1905, Citation1906b). To count the amount of nanoscopic particles, he used a coronal method to estimate the number concentration of monodisperse water droplets after expansion in the chamber: in such case, he could relate the aperture of the corona with a certain wavelength to the size, and thus concentration, of particles. See (Barus, Citation1905, Ch. 8) for details. His results were heavily criticized by Wilson (Citation1906), who deemed the expansion technique used by Barus unsuitable for a quantitative analysis. This criticism together with the following withdrawl of Barus from the scientific correspondence in his later papers, where only results were in a laconic manner reported (Lindsay, Citation1941), most likely accounts for the neglect of Barus’ contributions by aerosol scientists. From field and laboratory measurements, Barus anticipated several recent findings related to the nature of atmospheric NPF. He was apparently the first to use the term ‘nucleation’ to describe the formation of new particles in the atmosphere (Barus, Citation1902), although he used the term ‘nuclei’ to denote all fine particles that could be detected using his fog chamber, some of which may have been produced via homogeneous nucleation (or vapor-to-condensed matter transition without a thermodynamic barrier). In fact, when reporting experimental data, he used ‘nucleation’ to denote the estimated number concentration of particles. Also, contrary to the common belief at the time (Schröder and Wiederkehr, Citation1998), Barus (Citation1905, Citation1906a, pp. v–vii) argued that sulphuric acid, not ions, is the key species for atmospheric NPF, to the extent that a single H2SO4 molecule is enough to initiate particle growth (cf. Kulmala et al., Citation2006).

Fig. 2. The fog chamber used by Barus and his assistants for field measurements. C and q indicate the stopcock and end of inlet for the sampled air, while two stopcocks B (mainly) and F are used for the exhaustion. Water level is marked with w, chamber frame A is made out of waxed wood and e indicates the position of trunnions mounting the chamber, allowing rotation to wet the cotton cloth n lining the chamber. Reproduced from Barus (Citation1905, p. 129).

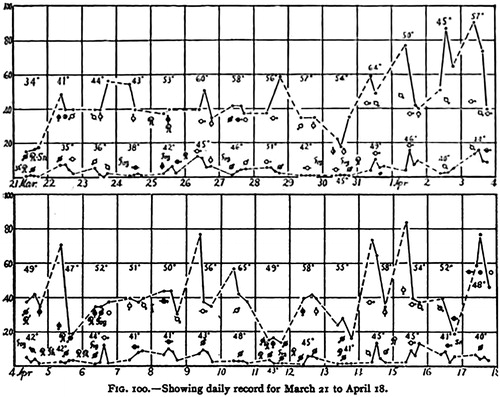

Although the numbers reported by Barus () seem to be in the range of modern measurements at comparable sites (Yu et al., Citation2014), the exact comparison is difficult as size-dependent losses and the effective upper and lower cut-off sizes for particles measured by Barus are hard to quantify, as no filter (in contrast to laboratory measurements) was applied in front of the atmospheric inlet. Nevertheless, the high number concentrations recorded certainly contain a significant amount of freshly formed particles. It should be noted that concerning the wintertime maxima in particle concentration, Barus (Citation1903, Citation1905, Citation1906a, Citation1906b) on several occasions acknowledges the potential role of the local combustion sources, producing either particles or sulphuric acid.

Fig. 3. An excerpt of simultaneous daily measurements in Providence (upper curves) and Block Island (lower curves) in spring 1905: the vertical axis gives the concentration as thousands of particles in cubic centimeter. Temperatures (in °F), wind directions, and prevailing weather are also indicated. Reproduced from Barus (Citation1906b, p. 125).

6. Discussion and conclusions

Sulphuric acid has been considered as a culprit for atmospheric particle formation since at least the early 18th century, with most studies until the end of 20th century relying on geological sources as the explanation of sulphur in the atmosphere. The role of SO2 from anthropogenic activities, mainly combustion, was considered by Aitken and Barus, who also pioneered atmospheric measurements of NPF. Laboratory measurements and theoretical development during the later part of the 19th century also helped to recognize the difference between nanoscopic, freshly formed particles and visible haze particles. Simultaneously, the development of atmospheric and photochemistry provided an explanation for sulphuric acid formation in the atmosphere, though details of relevant processes are still accumulating (Kulmala et al., Citation2014). A more direct proof on the role of sulphuric acid in atmospheric NPF was provided by Hogg (Citation1939), who noticed that intermediate air ions observed at Kew Observatory in London were composed of what seemed to be aggregates of tiny sulphuric acid droplets with a diameter of 3.6 nm. Considering the location and time, sulphur in the air was probably almost completely resulting from anthropogenic emissions; biogenic sources of sulphur were brought into consideration only during the later part of the 20th century (Eriksson, Citation1960; Charlson et al., Citation1987). Development of the chemical ionization mass spectrometry (Eisele and Tanner, Citation1993) finally led to the direct quantification of sulphuric acid molecules in the atmospheric and allowed one to establish the direct connection with NPF (Weber et al., Citation1996).

Historical explanations for atmospheric NPF were obviously not limited to sulphuric acid, but several competing hypotheses were put forward, some standing time better than others. For example, iodine and phosphorus, especially their acids, were suggested (Möller, Citation2014, p. 24) – and experimented (Tyndall, Citation1868; Barus, Citation1906a; Wilson, Citation1906) – by several researchers. The first quantitative experiments revealing the role of iodine oxides, after Tyndall’s (Citation1868) experiments with hydroiodic acid and organoiodic compounds, were performed by Owen and Pealing (Citation1911), who concluded that iodine causes formation of new particles, if oxygen and light are present. Another interesting finding of this research, further studied by Pealing (Citation1915), is the formation of particles in the apparatus after rinsing the glass bulb used as expansion chamber with water. Several potential sources of contamination were considered, and after Lenard and Ramsauer (Citation1911), ammonia was noted as possibly present in the water used in experiments and tending to adsorb on glass and metal surfaces, causing this effect (cf. Duplissy et al., Citation2010). This would further explain the fact that no effect was seen when sulphuric acid solution was used to rinse the glass bulb. Lenard and Ramsauer (Citation1911), in their own experiments, made a further interesting remark concerning the smell of methylamine in connection to particularly strong particle formation.

Selenium was also considered, not only because it is often found associated with sulphur in minerals and thus could be released in volcanic eruptions, but also due to its possible link to health effects related to dry haze; Prout (Citation1834, pp. 347–351) made here a reference to the initial description of selenium and its irritating properties when inhaled by Berzelius (Citation1818). However, by 1910 or so, sulphuric acid together with ammonia and water was widely accepted as the reason for new particle formation in the troposphere, which itself was found to be a regular phenomenon. Although these findings anticipated much of the recent work on the topic from the past quarter of the century, this information was largely neglected during the 20th century, to the extent of Butcher and Charlson (Citation1972, p. 159) stating that:

[T]he importance of homogeneous nucleation in the atmosphere is unknown at this juncture, but is probably important in only a few rare instances, possibly in the nearly dust-free upper atmosphere, or at points of emission to the atmosphere where the supersaturation is extremely high.

A timeline

In Table , timeline of main discoveries related to the role of sulphuric acid in atmospheric haze and new particle formation is provided.

Table 1. A concise timeline of discovering the role of sulphuric acid in atmospheric haze and new particle formation.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ari Laaksonen and Nønne Prisle for their thoughtful reading and comments on the earlier versions of the manuscript, and Jack Lin for proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For partial translations into English with commentary, see Reinhardt and Oldroyd (Citation1983).

2 With hindsight (cf. Husar, Citation2000; Alves, Citation2005), the most interesting theory along such lines was presented by Marcorelle (Citation1784), who concluded that condensing fermentation products of fumes from plants and soil, together with salt-like and ‘bituminous’ compounds were a major source of haze droplets, and that evaporation of water from such a droplet would leave a small, solid particle. Considering the lack of relevant measurements and understanding of organic chemistry at the time of writing, these thoughts are not far from the current understanding of the role of secondary organic compounds in the formation and growth of new particles (Shrivastava et al., Citation2017).

3 ‘From this viewpoint to the operations of the nature, according to which I have first and foremost tried to explain the formation of volcanic matter by the chemical combination of gaseous fluids circulating underground, which by the effect of MINERAL ASSIMILATION become stony and metallic bodies, analogously to those supposedly formed by the so-called wet way (1). Now this theory applies so naturally to the formation of the meteoric stones that I do not for a moment hesitate to consider it as perfectly identical with the formation of the substances emitted by volcanoes, i.e. by the chemical combination of various aeriform fluids.’

4 One should note that the first – and only – issue of the journal Western Minerva where this letter was intended to be published, was edited (and also to a large extent authored) by Rafinesque himself. It was censored immediately after printing due to rather obscure reasons, and did not see publication in its entirety until 1949. Rafinesque’s letter was first brought to the attention of atmospheric scientists by Abbe (Citation1900).

5 This is documented by a marking on a digital copy of which is available at https://archive.org/details/Onequilibriumhe00Gibb. It should be noted here that Gibbs’ work did not gain immediate recognition – possibly besides Maxwell, van der Vaals, and apparently Tyndall – in Europe (Müller, Citation2007, pp. 128–129).

6 The subtitle of this section was used by Carl Barus as a title of his autobiography (Barus, Citation2005), where he in a cynical manner notes that out of 1000 scientists, he is going to belong to the majority of 999 to be forgotten. This statement was apparently self-fulfilling, as not only did the manuscript of the autobiography remain forgotten for decades, but even Barus’ grand-nephew, famed atmospheric scientist Bernard Vonnegut, was not aware of his great-uncle’s contributions until a year before his own death (Vonnegut, Citation1998, Ch. 55)!

7 To some extent, one can say so about Robert von Helmholtz as well, though in this case, fewer mentions to his contributions in modern literature stem mainly from his untimely death during the work reported by Richarz (Von Helmholtz and Richarz, Citation1890). A short description Barus’ work in relation to atmospheric NPF is given below. For a more detailed overview, see Lindsay (Citation1941).Carl Barus was born in 1856 into a family of German immigrants and studied at the Columbia University and Universität Würzburg, from where he received his doctorate in 1879 under the guidance of Friedrich Kolrausch. In 1880 he returned to U.S. to work as a geophysicist for the Geological Survey, an appointment he held until his dismissal in 1892. Soon after he was made a professor in meteorology at the U.S. Weather Bureau, which marks also the beginning of his studies in the condensation of atmospheric moisture (Barus, Citation1893). This position, however, turned out to be a short-lived one, as it was dissolved already in the next summer. Barus then worked for the Smithsonian Institution as an assistant for S. P. Langley, until he was elected as a Hazard Professor of Physics at Brown University in 1895, which allowed him both to engage in teaching and to continue his studies related to atmospheric condensation phenomena started at the U.S. Weather Bureau. He continued to serve in this position and 1903 onwards as the dean of the graduate department until his retirement in 1926. During his career he become the youngest ever member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1892, received the Rumford Medal in 1900, and hold the office of the president of the American Physical Society in 1905–1906. Between 1893 and 1918 Barus published approximately one hundred articles and reports related to the atmospheric new particle formation, ions and condensation phenomena, the exact number depending on whether articles reporting only advances in measurement technology (e.g. hygrometry and interferometry) later applied into atmospheric studies are counted for.

References

- Abbe, C. 1900. Rafinesque on atmospheric dust. Mon. Weather Rev. 28, 291–292. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1900)28[291b:ROAD]2.0.CO;2.

- Aitken, J. 1881. On dust, fogs and clouds. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 30, 337–368. DOI:10.1017/S0080456800029069.

- Aitken, J. 1900. On some nuclei of cloudy condensation. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 39, 15–25. DOI:10.1017/S0080456800034025.

- Aitken, J. 1913. The Sun as a fog producer. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. 32, 183–215. DOI:10.1017/S0370164600012864.

- Alves, C. 2005. Aerossóis atmosféricos: Perspectiva histórica, fontes, processos químicos de formação e composição orgânica. Quím. Nova 28, 859–870. DOI:10.1590/S0100-40422005000500025.

- Aristotle (trans. R. W. Webster). 1931. Meteorologica. In: The Works of Aristotle (ed. W. D. Ross) Vol. 3. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Auzout, A. 1666. Lettre a Monsieur l’Abbe Charles. J. Sçavans. 2, 615–624.

- Barus, C. 1893. Colored cloudy condensation as depending on air temperature and dust-contents, with a view to dust counting. Am. Meteorol. J. 10, 12–34.

- Barus, C. 1902. Preliminary results on the changes of atmospheric nucleation. Science 16, 948–952. DOI:10.1126/science.16.415.948.

- Barus, C. 1903. The nucleation during cold weather. Phys. Rev. (Ser. I). 16, 193–198.

- Barus, C. 1905. A Continuous Record on Atmospheric Nucleation. Smithson. Contrib. Knowl. 34, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Barus, C. 1906a. Condensation nuclei. Phys. Rev. (Ser. I). 22, 82–110.

- Barus, C. 1906b. The Nucleation of the Uncontaminated Atmosphere. Carnegie Publ. 40, Carnegie Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Barus, C. 2005. One of the 999 about to Be Forgotten (ed. A. W.-O. Schmidt), AWOS Publishing, New York.

- Berzelius, J. J. 1818. Discovery of a new alkali and a new metal. Ann. Phil. 11, 291–293.

- Butcher, S. S. and Charlson, R. J. 1972. An Introduction to Air Chemistry. Academic Press, New York.

- Cao, J. J., Li, Y. K., Jiang, T. and Hu, G. 2015. Sulfur-containing particles emitted by concealed sulfide ore deposits: an unknown source of sulfur-containing particles in the atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6959–6969. DOI:5194/acp-15-6959-2015.

- Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O. and Warren, S. G. 1987. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature. 326, 655–661. DOI:10.1038/326655a0.

- Coulier, P. J. 1875. Note sur une nouvelle propriété de l’air. J. Pharm. Chim. 22, 165–178.

- Demarée, G. R. 2014. Haarrauch, un trouble atmosphérique ou un trouble environnemental et médical au XIXc siècle. In: La brume et le brouillard dans lascience, la littérature et les arts (eds. K. Becker and O. Leplatre). Les Éditions Hermann, Paris, pp. 129–143.

- Demarée, G., Nordlin, Ø., Malaquias, I. and Gonzalez Lopo, D. 2007. Volcanic eruptions, earth- & seaquakes, dry fogs vs. Aristotle’s Meteorologica and the Bible in the framework of the eighteenth century science history. Bull. Séanc. Acad. Sci. Outre-Mer. 53, 337–359.

- Duplissy, J., Enghoff, M. B., Aplin, K. L., Arnold, F., Aufmhoff, H. and co-authors. 2010. Results from the CERN pilot CLOUD experiment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 1635–1647. DOI:10.5194/acp-10-1635-2010.

- Eisele, F. L. and Tanner, D. J. 1993. Measurement of the gas phase concentration of H2SO4 and methane sulfonic acid and estimates of H2SO4 production and loss in the atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 9001–9010. DOI:10.1029/93JD00031.

- Elm, J., Myllys, N. and Kurtén, T. 2017. What is required for highly oxidized molecules to form clusters with sulfuric acid? J. Phys. Chem. A. 121, 4578–4587. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpca.7b03759.

- Eriksson, E. 1960. The yearly circulation of chloride and sulfur in nature; meteorological, geochemical and pedological implications. Part II. Tellus. 12, 64–109. DOI:10.3402/tellusa.v12i1.9341.

- Farkas, L. 1927. Keimbildungsgeschwindigket in übersättigten Dämpfen. Z. Phys. Chem. 175, 236–242. DOI:10.1515/zpch-1927-12513.

- Gibbs, J. W. 1875. On the equilibrium of heterogeneous substances. First part. Trans. Connect. Acad. Arts Sci. 3, 108–248.

- Harrison, G. 2011. The cloud chamber and CTR Wilson’s legacy to atmospheric science. Weather. 66, 276–279. DOI:10.1002/wea.830.

- Hogg, A. R. 1939. The intermediate ions in the atmosphere. Proc. Phys. Soc. 51, 1014–1026. DOI:10.1088/0959-5309/51/6/311.

- Hólm, S. M. 1784. Om Jordbranden Paa Island i Aaret 1783. Peder Horrebow, Copenhagen.

- Husar R. B., 2000. Atmospheric aerosol science before 1900. In: History of Aerosol Science (eds. O. Preining and E. J. Davis). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna, pp. 25–36.

- Kant, I. 1756a. Von der Ursachen der Erderschütterungen bei Gelegenheit des Unglücks, welches die westliche Länder von Europa gegen das Ende des vorigen Jahres betroffen hat. Wöchentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nacthrichten, January 24 and 31.

- Kant, I. 1756b. Geschichte und Naturbeschreibung der merkwürdigsten Vorfälle des Erdbebens, welches an dem Ende des 1755sten Jahres einen groszen Theil der Erde erschüttert hat. J. H. Hartung, Königsberg.

- Kant, I. 1802. Physische Geographie, Band 1 (comp. F. T. Rink). Göbbelns und Unzer, Königsberg.

- Karpenko, V. and Norris, J. A. 2002. Vitriol in the history of chemistry. Chem. Listy. 96, 997–1005.

- Kiessling, J. 1884. Nebelglüh-Apparat. Abh. Naturwiss. Vereins Hamburg–Altona. 8, 147–154.

- Knowles Middleton, W. E. 1964. Chemistry and meteorology, 1700–1825. Ann. Sci. 20, 125–141. DOI:10.1080/00033796400203024.

- Kulmala, M., Lehtinen, K. E. J. and Laaksonen, A. 2006. Cluster activation theory as an explanation of the linear dependence between formation rate rate of 3 nm particles and sulphuric acid concentration. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 787–793. DOI:10.5194/acp-6-787-2006.

- Kulmala, M., Petäjä, T., Ehn, M., Thornton, J., Sipilä, M. and co-authors. 2014. Chemistry of atmospheric nucleation: on the recent advances on precursor characterization and atmospheric cluster composition in connection with atmospheric new particle formation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 65, 21–37. DOI:10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110014.

- Kulmala, M., Vehkamäki, H., Petäjä, T., Dal Maso, M., Lauri, A. and co-authors. 2004. Formation and growth rates of ultrafine atmospheric particles: a review of observations. J. Aerosol Sci. 35, 143–176. DOI:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2003.10.003.

- Kupiainen-Määttä, O., Olenius, T., Korhonen, H., Malila, J., Dal Maso, M. and co-authors. 2014. Critical cluster size cannot in practice be determined by slope analysis in atmospherically relevant applications. J. Aerosol Sci. 77, 127–144. DOI:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2014.07.005.

- Lémery, N. 1703. Explication physique et chymique des feux souterrains, des tremblemens de terre, des ouragans, des eclairs & du tonnere. Hist. Acad. R. Sci. Mem. Math. Phys. 1700, 101–110.

- Lenard, P. and Ramsauer, C. 1911. Über die Wirkungen sehr kurzwelligen ultravioletten Lichtes auf Gase und über eine sehr reiche Quelle dieses Lichtes. Teil IV. Über die Nebelkernbildung durch Licht in der Erdatmosphäre und in anderen Gasen, und über Ozonbildung. Sitzungsber. Heidelb. Akad. Wiss. Math. Naturwiss. Kl. A 16, 1–27.

- Lindsay, R. B. 1941. Carl Barus. Biogr. Mem. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 22, 169–213.

- Lucretius (trans. W. E. Leonard). 1916. De Rerum Natura. E. P. Dutton & Co., New York.

- Marcorelle, B. D. 1784. Description d’un brouillard extraordinaire qui a paru fur la fin du mois de Juin, & au commencement de celui de Juillet 1783. Obs. Phys. Chim. Hist. Nat. Arts. 24, 18–23.

- Marvin, D. C. and Reiss, H. 1978. Cloud chamber study of the gas phase photooxidation of sulfur dioxide. J. Chem. Phys. 69, 1897–1918. DOI:10.1063/1.436827.

- Mohnen, V. and Hidy, G. M. 2010. Measurements of atmospheric nanoparticles (1875–1980). Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 91, 1525–1539. DOI:10.1175/2010BAMS2929.1.

- Möller, D. 2014. Chemistry of the Climate System. 2nd ed. De Gruyter, Berlin.

- Mourgue de Montredon 1784. Sur l’origine & sur la nature des vapeurs qui ont régné dans l’atmosphère pendant l’été. Hist. Acad. R. Sci. Mem. Math. Phys. 1781, 754–773.

- Müller, I. 2007. A History of Thermodynamics.Springer, Berlin.

- Oeser, E. 1992. Historical earthquake theories from Aristotle to Kant. In: Historical Earthquakes in Central Europe (eds. R. Gutdeutsch, G. Grünthal and R. Musson) Vol. 1. Geologische Bundesanstalt, Vienna, pp. 11–31.

- Owen, G. and Pealing, H. 1911. On condensation nuclei produced by the action of light on iodine vapour. Phil. Mag. (Ser. 6) 21, 465–479. DOI:10.1080/14786440408637054.

- Patrin, E. M. L. 1809. A l’occasion des pierres météoriques ou météorilites. J. Phys. Chim. Hist. Nat. Arts. 68, 401–408.

- Pealing, H. 1915. On condensation nuclei produced by the action of light on iodine vapour. Phil. Mag. (Ser. 6) 29, 413–419. DOI:10.1080/14786440308635320.

- Plinius Secundus, G. (Pliny the Elder). 1906. Naturalis Historia (ed. K. F. T. Mayhoff). Teubner, Leipzig.

- Podzimek, J. 1989. John Aitken’s contribution to atmospheric and aerosol sciences—One hundred years of condensation nuclei counting. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 70, 1538–1545. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477(1989)070<1538:JACTAA>2.0.CO;2.

- Prager, M. J., Stephens, E. R. and Scott, W. E. 1960. Aerosol formation from gaseous air pollutants. Ind. Eng. Chem. 52, 521–524. DOI:10.1021/ie50606a034.

- Preus, 1785. Observationes Saganenses. Ephemer. Soc. Meteorol. Palatinae. 3, 330–370.

- Prout, W. 1834. Chemistry, Meteorology and the Function of Digestion. Bridgewater Treat. VIII, William Pickering, London.

- Rafinesque, C. S. 1819. Thoughts on atmospheric dust. Am. J. Sci. 1, 397–400.

- Rafinesque, C. S. 1821. Letters on atmospheric dust. West. Minerva. 1, 27–29.

- Reinhardt, O. and Oldroyd, D. R. 1983. Kant’s theory on earthquakes and volcanic action. Ann. Sci. 40, 247–272. DOI:10.1080/00033798300200221.

- Renzetti, N. A. and Doyle, G. J. 1960. Photochemical aerosol formation in sulfur dioxide–hydrocarbon systems. Int. J. Air Pollut. 2, 327–345.

- Rubin, M. B. 2001. The history of ozone. The Schönbein period, 1839–1868. Bull. Hist. Chem. 26, 40–56.

- Schönbein, C. F. 1837. On the odour accompanying electricity and on the probability on its dependence on the presence of a new substance. Phil. Mag. (Ser. 3). 4, 226–294.

- Schröder, W. and Wiederkehr, K. H. 1998. Geophysics contributed to the radical change from classical to modern physics 100 years ago. Eos. Trans. AGU 79, 559–562. DOI:10.1029/98EO00411.

- Schröder, W. and Wiederkehr, K. H. 2000. Johann Kiessling, the Krakatoa event and the development of atmospheric optics after 1883. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 54, 249–258. DOI:10.1098/rsnr.2000.0110.

- Senebier, J. 1784. Sur la vapeur qui a régné pendant l’eté de 1783. Obs. Phys. Chim. Hist. Nat. Arts. 24, 401–411.

- Shrivastava, M., Cappa, C. D., Fan, J., Goldstein, A. H., Guenther, A. B. and co-authors. 2017. Recent advances in understanding secondary organic aerosol: implications for global climate forcing. Rev. Geophys. 55, 509–559. DOI:10.1002/2016RG000540.

- Soulavie, G. 1783. Lettre de M. l’Abbé Giraud Soulavie au R. P. Cotte, de l’Oratoire, Curé de Montmorency. Journal de Paris July 21 and 22.

- Stothers, R. B. 1996. The great dry fog of 1783. Clim. Change. 32, 79–89. DOI:10.1007/BF00141279.

- Thomson, W. (lord Kelvin). 1871. On the equilibrium of vapour at a curved surface of liquid. Phil. Mag. (Ser. 4). 42, 448–452. DOI:10.1080/14786447108640606.

- Thordarson, T. and Self, S. 2003. Atmospheric and environmental effects of the 1783–1784 Laki eruption: a review and reassessment. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4011. DOI:10.1029/2001JD002042.

- Toaldo, 1785. Observationes Patavienses. Ephemer. Soc. Meteorol. Palatinae. 3, 546–590.

- Tyndall, J. 1868. On a new series of chemical reactions produced by light. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 17, 92–102. DOI:10.1098/rspl.1868.0012.

- Tyndall, J. 1870. On the action of rays of high refrangibility upon gaseous matter. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 160, 333–365. DOI:10.1098/rstl.1870.0019.

- Tyndall, J. 1881. Essays on the Floating Matter in Air in Relation to Putrefaction and Infection. Longmans, Green, and Co., London.

- Van Swinden, 1785. Observationes nebulam, quae mense Junio 1783 apparuit, spectantes. Ephemer. Soc. Meteorol. Palatinae 3, 679–688.

- Virey, J. J. 1803. Nature. Nouv. Dict. Hist. Nat. 15, 358–414.

- Volmer, M. and Weber, A. 1926. Keimbildung in übersättigten Gebilden. Z. Phys. Chem. 119, 277–301. DOI:10.1515/zpch-1926-11927.

- Von Helmholtz, R. 1886. Untersuchungen über Dämpfe und Nebel, besonders über solche von Lösungen. Ann. Phys. Chem. 263, 508–543. DOI:10.1002/andp.18862630403.

- Von Helmholtz, R. 1887. Versuche mit einem Dampfstrahl. Ann. Phys. Chem. 268, 1–19. DOI:10.1002/andp.18872680902.

- Von Helmholtz, R. and Richarz, F. 1890. Über die Einwirkung chemischer und electrischer Processe auf den Dampfsthral und über die Dissociation der Gase, insbesondere der Sauerstoffs. Ann. Phys. Chem. 276, 161–202. DOI:10.1002/andp.18902760602.

- Vonnegut, K. 1998. Timequake.Vintage, London.

- Wang, C. C., Davis, L. I., Wu, C. H., Japar, S., Niki, H. and co-authors. 1975. Hydroxyl radical concentrations measured in ambient air. Science. 189, 797–800. DOI:10.1126/science.189.4205.797.

- Warneck, P. 1974. On the role of OH and HO2 radicals in the troposphere. Tellus. 26, 39–46. DOI:10.3402/tellusa.v26i1-2.9735.

- Weber, R. J., Marti, J. J., McMurry, P. H., Eisele, F. L., Tanner, D. J. and co-authors. 1996. Measured atmospheric new particle formation rates: implications for nucleation mechanisms. Chem. Eng. Commun. 151, 53–64. DOI:10.1080/00986449608936541.

- Wilson, C. T. R. 1897. Condensation of water vapour in the presence of dust-free air and other gases. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 189, 265–307. DOI:10.1098/rsta.1897.0011.

- Wilson, C. T. R. 1906. Condensation nuclei. Nature. 74, 619–621. DOI:10.1038/074619b0.

- Yu, H., Gannet Hallar, A., You, Y., Sedlacek, A., Springston, S. and co-authors. 2014. Sub-3 nm particles observed at the coastal and continental sites in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 860–879. DOI:10.1002/2013JD020841.

- Zhang, R., Khalizov, A., Wang, L., Hu, M. and Xu, W. 2012. Nucleation and growth of nanoparticles in the atmosphere. Chem. Rev. 112, 1957–2011. DOI:10.1021/cr2001756.