ABSTRACT

We argue that a shift in the underlying values that inform people’s actions in the public sphere is taking place in the social media age. From ways of qualifying the public sphere as a space that prioritizes equality, mutual respect and careful deliberation, action that creates visibility, attention and followership is increasingly valued above all else. This change translates into a transformation of the public sphere that requires revisiting the conceptual tools of democratic publics. In contrast to the Habermasian normative approach, we suggest that an empirically grounded definition of the public sphere, discernible with tools from justification theory, enables identifying a wider variety of public actions and interrogating the different moral foundations of public spheres. Based on ongoing research on visual politicization, we argue that the world of fame increasingly challenges the valuation logics of the market and the civic worlds as the value base informing public action. We illustrate our argument with examples from our ethnographic work on social media activists, the figure of an influencer/politician, and social media actors countering the algorithmic logic of the present public sphere. Finally, we discuss these transformations’ consequences to democracy theory. We suggest a way towards a democracy theory which includes a plurality of arguments and values—even ones that may threaten democracy—as a remedy to the potentially blinding effects of civic normativity.

Introduction

The most successful form of activism on Instagram is pop activism. It needs to be clear, entertaining and easy to understand. Your biggest goal is visibility, and your biggest threat is invisibility. To get visibility, you need to be innovative, authentic and funny. Be active because the algorithms will reward you for that. Try to create content that people will want to share.

(Training on Instagram activism for an activist group, 20.10.2022)

LAURA JUST STARTED FOLLOWING US ON INSTAGRAM, my life is perfect for a moment ![]()

WOOPWOOP.

(Discussion on mental health activists’ WhatsApp group, 21.10.2020)

In this article, we argue that in examples such as the above, we are seeing a shift in the undergirding values that inform people’s actions in the public sphere. Social media, with their algorithmic materialities and attention-oriented logic (Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013; Eranti and Lonkila Citation2015; Malafaia and Meriluoto Citation2022), have introduced a new primary value base for the public sphere that fundamentally alters the ways in which political action is organized. From ways of qualifying the public sphere as a space that prioritizes equality, mutual respect and careful deliberation, qualifying public action now increasingly leans towards valuing action that creates visibility, attention and followership. Using conceptual tools from justification theory in French pragmatist sociology (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991), we argue that the world of fame is now increasingly challenging the valuation logics of the market and the civic worlds. While the democratic public sphere has been a composite of the fame and civic worlds ever since the invention of public opinion (see Habermas Citation1991, e.g. 25–26), we argue that we are today seeing the tipping of scales between the two, with the logic of fame assuming the position of the primary value base that informs public action. This echoes the original mass media society critique of Habermas, but we argue that it requires new conceptual effort.

The Habermasian normative ideal of a rational, impartial and equal public sphere—a space for deliberation—remains a measuring stick for a ‘healthy’ democracy (Habermas Citation1991; Dahlberg Citation2005). At the same time, current analyses, and not just ours, diagnose the public sphere as falling short of this ideal on all fronts and in novel ways. Today’s public sphere fostered by social media logic is described as polarized (Bail Citation2021), individualized (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012), transmuted into bubbles or echo chambers (Rhodes Citation2022) and algorithmically rigged to produce inequality (Merten et al. Citation2022). This mismatch between a normative ideal and the empirical reality has been one of the key arguments of research on the public sphere (e.g. Fraser Citation1990). Habermas himself, mapping the ills of mass media–driven public sphere, declared the market-driven public sphere to be that ‘in appearance only’ (Citation1991, 171), as negotiation between private interests took the place of civic debate (ibid., 198). Individual interests, Habermas argued, came to challenge the civic values of the eighteenth century coffeehouses that he considered to epitomize democracy’s values in practice.

Based on our present research, we argue that a transformation similar to the one outlined by Habermas is underway today with the social media–driven public sphere. However, instead of addressing this change from a normative point of departure with Habermas, we position it as our pragmatist object of inquiry into action constituting the public sphere. We suggest that such an empirically grounded approach to the public sphere will enable us to identify a wider variety of public actions as public action, allowing us to interrogate the different moral foundations of public spheres and their transformations in action (see also Luhtakallio & Eranti et al., forthcoming).

A fame-based democratic public sphere may propel us to consider the plurality of possible value bases as an asset for democracy instead of perceiving all changes to the civic–rational ideal as a threat to the democratic foundations of public debate. While the threats already recognized by Habermas and many other critical authors—from Baudrillard to Adorno and Arendt—are certainly valid today and should not be dismissed, we suggest that what these critiques overlook is the radical potential that a fame-based democracy may carry to open the value bases of democracy up for a democratic debate. The pragmatic sociology concepts we work with enable us to explore such an extension to the understanding of the public sphere due to the inherent value plurality of the theoretical approach: we suggest thus avoiding the blinding effect of normative democracy theories that tend to exclude morally un-civic or, in various ways, unsavoury elements from the realm of theorizing an ‘actually democratic’ public sphere.

We start by discussing the public sphere as a conceptual tool for understanding political action and consider how its normative foundations have thus far been explored. We then take a different route and start conceptualizing today’s public sphere from the ground up, exploring visuality as its key feature. We introduce justification theory as our conceptual toolkit for making sense of an inherently value-plural public sphere. To substantiate our argument, we explore how the meanings assigned to two key features of public action—visibility and authenticity—are negotiated in today’s fame-based public sphere. We conclude by considering how the suggested transformation informs and reshapes democracy theory on the one hand and political action on the other.

Democratic public sphere

The Habermasian concept of the public sphere is a tool for interrogating political life: under which conditions can ‘the arguments of mixed companies’ become the basis of authoritative political action (Calhoun Citation1992, 1). According to Nancy Fraser, it ‘designates a theatre in modern societies in which political participation is enacted through the medium of talk. It is the space in which citizens deliberate about their common affairs, hence, an institutionalized arena of discursive interaction.’ (Fraser Citation1990, 57; also Adut Citation2012, 239; Oliver and Myers Citation1999, 38). This notion of the public sphere is distinct from the state, the economy and ‘the private sphere’ and has thus provided the cornerstone for democratic theorizing that seeks to denote public action that does not take place between state apparatuses or in economic markets (e.g. Fraser Citation1990, 57).

While the Habermasian understanding of the public sphere has also been the object of critique from several fronts targeting, for example, its unproblematized distinction between the public and the private (eg. Fraser Citation1990; Schudson Citation1992), the unfounded and marginalizing allusion to a single public sphere (Fraser Citation1990, 67; Bruns and Highfiel Citation2015) and its empirically ungrounded normative premise (Fraser Citation1995, Citation2013, Citation2014; Canaday Citation2003; Lara and Fine Citation2007; Mansbridge Citation2017), these critiques often overlook Habermas’ own critical stance. Although his approach to the ‘original’ bourgeois publicity, born in literary circles in eighteenth century Europe, can be deemed to be romanticizing of these origins (see Schudson Citation1992), the core of his critique was aimed at the ills of the mass media society and the degeneration of the values of the bourgeois public sphere. This degeneration by means of the marketization of society—later in Habermas’ thinking the colonization of the life world—resulted in a transformation of the basis of political decision-making from rational public deliberation into the manipulative competition of interests (Habermas Citation1991, 169, 175; Calhoun Citation1992, 21–23). This part of Habermas’s theorizing, despite being well known and present in mass media critique, has had a less explicit place in the discussion of his public sphere theory. Consequently, the critique of the public sphere theory has, put bluntly, concentrated on evaluating the ‘morally admirable but analytically useless’ concept of the bourgeois public sphere by Habermas (Emirbayer and Sheller Citation1998).

This line of critique, as well as, undeniably, the Habermasian conceptualization of the original, unspoiled public sphere itself, is normatively tied to what Ari Adut (Citation2012, 239) calls ‘the condition of civicness’. He points out how most scholars employing the concept use it to refer to ‘open-ended and public-spirited communication’ (Baiocchi Citation2003, 55) or ‘public-spirited speech’ (Eliasoph Citation1998, 16). Nicholas Garnham (Citation2007, 206) equally argues that the Habermasian ideals of ‘undistorted communication’ and ‘communicative rationality’ are connected to the idea of modernity as alienation that pines for ‘a healthy human essence’ unspoiled by the mediated modern society. This reflects the Frankfurt school programme and especially the (necessary and continuously in many ways pertinent) post-Holocaust normative theorizing of modernity (see Arendt Citation1951, Citation1958).

We argue, however, that the condition of civicness ties the concept of the public sphere to a normative pre-commitment that may hinder us from identifying and exploring the public sphere of ‘actually existing democracies’ (see Adut Citation2012, 239–240; also Emirbayer and Sheller Citation1998, 729). This is becoming increasingly problematic in the material and ideological complexities and plural publicities of late modern societies, whose analysis would require a conceptual toolkit capable of dealing with the plurality of normative foundations. What follows is that a normatively tight conceptualization of the public sphere will inevitably leave us analysing political action with one eye blinded and will not enable us to discuss changes in the moral foundations of public action in other than evaluative terms – as threats to democracy.

In response, Ari Adut (Citation2012, Citation2018) has sought to ‘theorize and operationalize the public sphere in a way that is morally void but analytically useful’ (Citation2012, 238). To this end, Adut proposes a definition that is not built on the quality of the discourse or the level of equality among participants but on ‘general sensory access’ (ibid.). Adut (Citation2018, 15, 17–18) argues: ‘The public sphere is simply where we are visible. By visible, I mean open to sensory access, open to the sight of spectators, in one’s body or representation.’ We take the visibility suggested by Adut as our point of departure, suggesting that it is a feature that is almost entirely lacking in the Habermasian tradition. This lack of consideration of visibility and visuality in the definition and the theory’s exclusive focus on text and speech (see, e.g. Fraser Citation1990, 57 quoted above) has become empirically increasingly problematic. This is one of the symptoms of the current transformation, making the shaft between normative democratic theorizing and ‘actually existing democracy’ even wider.

In this article, instead of following Adut’s ‘morally void’ definition of the public, we push his approach further towards analysing the current moral foundations of the public sphere. We suggest that while a simple, empirically grounded definition of the public sphere will enable us to identify a wider variety of public action as public action, it is crucial to interrogate the different—and plural—moral foundations of public spheres in action. Adut’s realist perspective has enabled him to illuminate the civic foundations of the conventional perspective on the public sphere (Citation2018, 4). We suggest that furthermore, we need to uncover the changing values conditioning people’s public action and, as such, the different moral foundations of the public sphere in existing democracies.

Social media public sphere: fame, visibility and performance

To start building a pragmatist understanding of the public sphere, we start with the literature exploring the key features of today’s public sphere: its visual character, performativity and fame-based logic. We operate with an understanding of the public sphere as a hybridized online/offline space in which the distinction between ‘the two spheres’ is decreasingly meaningful or even ontologically salient (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022).

Today’s public sphere is increasingly dominated by visual content. This heightened visuality is perhaps most evident on social media. Martin Hand (Citation2020, 311) notes how social media platforms as diverse as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat are all primarily visual media and how, as a result, social media use has become ‘a matter of visual communication’. Consequently, the forms and dimensions of visual content in everyday communication about politics have multiplied (Jenkins and Zimmerman Citation2016; Russmann and Svensson Citation2017; Lenhart Citation2015; Allaste and Tiidenberg Citation2015). At the same time, pictures and videos themselves politicize: protests, demands, arguments and even entire processes of politicization may take a purely visual form (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022). The increasing significance of visuality has also shaped politicians’ public action towards tools that foreground aesthetics and style, as well as performances of proximity and intimacy (Wheeler Citation2012; Street Citation2004).

In addition to visuality, social media follows a fame-based algorithmic logic (e.g. Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013; Eranti and Lonkila Citation2015; Van Dijck Citation2013). Social media as a technical infrastructure and culture—‘a virtual public sphere’ (Papacharissi Citation2002)—awards posts with the most likes, shares and comments with more visibility. On social media, ‘the success’ of an argument is determined by how widely it is liked/shared (Marwick Citation2015), which significantly shapes public action in this environment: posts are composed with likeability and ‘shareability’ in mind (Malafaia and Meriluoto Citation2022). This is indeed necessary, as posts that do not receive any reactions quite concretely are hidden away by the algorithm. On social media, attention equals existence.

While some scholars have interpreted the potential of social media as equalizing the possibility of attracting attention previously reserved to those who could harness the power of mass broadcasting companies, other studies have shown that social media often reproduce conventional status hierarchies, as those who succeed in gaining attention and followership tend to be people who have the resources to imitate mainstream celebrity culture (Marwick Citation2015). Alice Marwick (Citation2015, 141) writes: ‘Instafame is not egalitarian but rather reinforces an existing hierarchy of fame, in which the iconography of glamour, luxury, wealth, good looks, and connections is reinscribed in a visual digital medium. The presence of an attentive audience may be the most potent status symbol of all.’

These two features—the increasing visuality and the logic of fame—are connected. If, as in Adut’s definition (Citation2018, x), the public sphere is ‘simply a space of appearances’ that immediately mutates a dialogue into a spectacle with the presence of an audience, it follows that ‘competition for distinction, if not sheer fame, is at its very core.’ (Adut Citation2018, 21). Adut, then, places fame, not civic-mindedness or equality, as the foundational value base of the public sphere. A theorist of fame, Leo Braudy (Citation1986, Citation2011), equally finds an inseparable connection between visibility and fame in post-Renaissance Western culture, arguing that with the increasing democratization of fame, ‘the idea of fame without visibility seems like an unsupportable paradox’ (Citation2011, 1072).

Indeed, visual social media’s communicative logic is that of performativity (e.g. Wellman Citation2022), and its power resides in visibility, felicitousness and virality (Milan Citation2015). Testing the validity of rational arguments is replaced by the performative position of individuals. The dimension of power thus surfacing is performative: power that appears through well-timed action that creates events and that has consequences for future action (Reed Citation2013). Furthermore, performatively powerful action requires the skill to style and frame events as noticeable and creates, as a very concrete consequence, followers for future actions. Paraphrasing Habermas, where communicative action relying on rational argumentation aims at understanding, the one relying on performativity aims at maximizing fame, publicity, dissemination of the message and the number of followers.

The competition for visibility, attention and public esteem can persuasively be argued to have always formed a part of public action. Habermas, when discussing the public sphere of ancient Greeks, granted that while ‘citizens interacted as equals, each did his best to excel. The virtues, whose catalogue was codified by Aristotle, were ones whose test lies in the public sphere and there alone receive recognition’ (Citation1991, 4). What follows is that the hybrid between civic values and a logic of fame that we now see emerging as increasingly prevalent in social media are built in actions characteristic to the democratic public sphere. For many democratic theorists, however, the logic of fame has presented a problem or has been disregarded altogether as antithetical to the democratic public sphere.

We suggest that the visual social media–driven public sphere is currently tipping the scales of democracy’s built-in tension between civic and fame-based logic. If, as we argue, such a shift in emphasis is occurring, the momentous question that follows is, what are the consequences thereof to democracy, not only on the level of ideals but also on the level of everyday practices that constitute the constellation of actions, habits and institutions of democracy? To explore this and to respond to the above-set ambition to pluralize the current normative approach to the moral foundations of democracy, we suggest employing conceptual tools from justification theory (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991). In the following section, we first revisit the theory’s pragmatist groundings and then develop especially on fame and civic repertoires of valuation.

Justifying based on fame

Built originally as a critical response to Bourdieu’s structural approach and following pragmatist reasoning, the justification theory grants actors critical capacity (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991). This capacity renders them creative as individual actors in everyday conflict situations and as communities in long-term transformations and crises, searching for compromises and ways to live together despite their irredeemable differences. Both aspects of rupture illustrate the foundational character of the public: it is value pluralistic, and in order to settle controversies, people have to justify their points of view, prepared to meet others’ viewpoints that are justified from within a differing set of valuations.

The justification theory addresses public conflicts by studying, on a pragmatic basis, the repertoires of evaluation people use to resolve controversies. The theory has thus far identified nine ‘orders of worth’ or ‘worlds of justification’, i.e. recurring, different value bases: domestic, industrial, market, civic, inspiration, fame, green and project, of which the first six were included in the original presentation and the last two added at later phases (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991; Lafaye and Thévenot Citation1993; Boltanski and Chiapello Citation1999). These orders of worth provide criteria against which actions, items and people can be evaluated in ‘reality tests’ that measure them against concrete manifestations of worth in the real world—for example, representativeness or equality in the realm of civic worth (Centemeri Citation2017; Ylä-Anttila and Luhtakallio Citation2016).

Originally in justification theory, these value bases are grounded on thinkers of (Western) political philosophy so that each principle of justice stands on its own theoretical basis. This grounding reflects the value plurality of the theory: it encompasses a historical array of the plurality of normative bases that are not only possible but have influenced the very development of the thinking and theorizing of the public sphere. While Adam Smith’s thinking is the starting point for a justified valuation of money and the ‘market world’ above all else, Saint-Simon is the thinker who Boltanski and Thévenot identify as the most comprehensive source for the ‘industrial world’ and justifications based on efficiency and scientific expertise (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991, 244–245, 252–254; Ylä-Anttila and Luhtakallio Citation2016). Further on, the eighteenth-century French philosopher Bossuet provides for the domestic worth based on tradition, personal relationships, inherited status, intimacy and hierarchy, and St. Augustine for the inspired worth in which the highest value is in spiritual commitment, independence and indifference towards market goods and personal dependencies (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991, 201, 207–208; Ylä-Anttila and Luhtakallio Citation2016).

The civic world is a value base that Boltanski and Thévenot (Citation1991, 231–233, 237) spell out with a close reading of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract (Citation1980 [1762]). In this value base, the will of the people, collective well-being and collectives over individuals are to be valued above all else. In the civic world, greatness is equality among all people, sticking to agreements and solidarity. Naturally, this conception of the civic has many siblings in theorizing the public and democracy. In the recent US cultural sociology in particular, the variety of conceptual work from the civil sphere to civic action and civic imagination (Alexander Citation2006; Lichterman and Eliasoph Citation2014; Lichterman Citation2020; Baiocchi et al. Citation2014) are all part of a ‘family’ of theorization of the tools (see also Swidler Citation1986) that groups, cultures and societies have at their disposal in striving towards change through (some form of) political action. Clearly, in justification theory, the civic worth is not just one value base among others but has wide resonance in contemporary theorizing about the organization of the will of the people.

Indeed, one of the central debates on and within justification theory has been the role of the civic world as a ‘metacategory’ in the theory—not unlike the implicit normative grounding of most democratic theorizing. Justification theory posits the recognition of a ‘common humanity’ as a prerequisite for any justificatory action in the public sphere. Thus, it is said to take a Habermasian normative ideal of equal standing between parties as its starting point despite the theory’s central claim of plurality of worth (e.g. Ricoeur Citation1995). Ricoeur (Citation1995) and many after him (see, e.g. Ylä-Anttila and Luhtakallio Citation2016; Luhtakallio and Ylä-Anttila Citation2023) have pointed out how the theory, while denying all normative stances, implicitly takes civic worth as a point of departure. This happens, for instance, through the theory stating that justifying is a critical capacity that all people have equally. The implicit civic value base is also evident in the very idea that justifying is necessary and possible, based on the assumption of mutually recognized common humanity. As critiques of the Habermasian public sphere have already done, it is easy to point out that this is empirically not always so.

Metacategory, then, here means that while justification theory itself is based on the plurality of the common good, the architecture of justification implies certain preconditions for an evaluation of common goods to take place. To exemplify, we can have a dispute in which we only argue whether one solution is financially better than the other—so there is no civic ‘hegemony’ over the processes of justification—but we do, nonetheless, assume that there are common rules and that the opponent has an equal right to argue and justify. Therefore, civic worth has a dual role in justification theory, and this feature has consequences for our argument of the public sphere bending increasingly to another valuation basis: fame.

In the world of fame, greatness is – fame: number of followers, being popular and known by many, indeed, being famous. The philosophical origins of the worth of fame in justification theory are in Thomas Hobbes’s thinking—its measure of greatness is thus somewhat an antithesis to that of civic worth. In Leviathan, Hobbes is said to define the guiding principle of people’s motivation for common action as having glory in the eyes of others (e.g. McClure Citation2014). The measure of worth is thus the recognition gained from as many followers as possible. Practices proper to the world of fame that Boltanski and Thévenot mention are, for instance, opinion polls that function both as identifications of fame—which opinion is the most followed—and as tools of increasing fame through the (usually mediatized) reporting on fame.

In Habermas’s description of the degeneration of the public sphere, the change in the role (and nature) of public opinion had key importance. Once the political public sphere began to serve rather than dissolve the division of power, the danger of public opinion swallowing up all power began to present itself, and the risk of popularity beginning to equal power emerged (Habermas Citation1991, 136). Public opinion, and thus the logic of fame as presented above, was early on considered a threat to the civic base of the public sphere. While in Habermas’ analysis, the critique is primarily about the market logic that takes over the public sphere with mass media, commercials and the birth of the Public Relations industry, alongside rise concerns that closely resemble the definitions Boltanski and Thévenot give to the fame worth. Habermas notes: ‘Public relations do not genuinely concern public opinion but opinion in the sense of reputation. The public sphere becomes the court before who public prestige can be displayed – rather than in which public critical debate is carried on’ (ibid. 200–201).

We suggest that in a social media–driven public sphere, fame becomes the dominating value principle of the public sphere. The quantification of visibility in the form of likes, shares and comments makes social media a fundamentally fame-based environment of valuation. This creates tension between the civic-based idea of democracy and the practices constituting its everyday manifestations. We argue that this logic increasingly conditions political action today. In the following section, we explore the clashes and hybrids between the civic and fame-based logics of public action, considering their repercussions for democracy.

Illustrations of fame-based public action

To substantiate our argument and to empirically explore the tipping of scales between fame and civic worth as the dominant values of the democratic public sphere, we provide illustrations from ongoing research on visual political action on social media (Malafaia and Meriluoto Citation2022; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022; Luhtakallio, Meriluoto, and Malafaia Citation2023; Meriluoto Citation2023; Malthezos et al. Citation2023). The research comprises ethnographic fieldwork conducted among young activists in four European countries, as well as ethnography-trained deep learning analysis of social media images. The focus of this research is to understand and theorize visual political action. The illustrations and extracts used originate from our fieldwork among activist groups in Finland and France, in addition to a Twitter-based analysis of a political scandal around the former Finnish PM.Footnote1 The examples were chosen as representative illustrations of the kinds of negotiations on and justifications of the values informing political action that we encountered widely during the fieldwork. However, we do not engage in empirical analyses below but provide brief snapshots from our empirical material to illustrate the change towards a fame-based public sphere.Footnote2

We draw on the fieldwork on these two activist groups because both groups are newly established and have fewer precedents in terms of objectives and ways of organizing than activist groups in more established areas of social movement contention. Because they have little to go by in terms of prior examples and models, they are in a process of constant self-definition and thus foster regular discussions on who the group members are, what its values are, and what the group aspires to. As the groups’ cultures cherish deep discussions on values, the data offer us a vantage point to explore how the actors themselves assign value to public action and how these valuations shape their own political activities. Our second example – a recent social media–based political scandal, the ‘partygate’, of the former Finnish PM Sanna Marin – on the other hand, illustrates the figure of the politician–influencer with its new fame-based requirements of visibility management and a new kind of power potential.

We suggest that the change in the public sphere becomes perceptible in the meanings assigned to two key concepts that characterize action in the public sphere that increasingly follows a fame-based logic: visibility and authenticity. Below, we explore the meanings assigned to these concepts and portray the change in the values informing the public sphere.

Visibility above all else

Our first examples discuss how the meaning and role of visibility have changed between a civic–rational public sphere and the now increasingly dominant fame-based public. We start with an example from our fieldwork with young mental health activists in Finland.Footnote3 We show how the group recognizes the rationale of civic values as ‘the original’ measuring stick for the value of political action but increasingly opts for activities that instead appear valuable within a fame-based logic. This, we argue, becomes visible in how the meaning of visibility changes from a tool of dialogue to the ultimate objective of political action. Our second example of the role of visibility discusses the ‘visibility scandal’ of the former Finnish PM, Sanna Marin.

Below, mental health activists discuss the group’s values in a meeting organized to ‘draft the group’s operating principles and values’. A key concept whose meaning and role are negotiated is visibility. During the discussion, the debate boiled down to a question about party representatives: whether it would be okay to invite representatives from right-wing parties to the group’s events. In the conversation, the civic demand for a space of dialogue clashes with the fame-based logic of promotion, resulting in a rather uneasy compromise in the form of ‘different kinds of collaboration’:

I think the key question is what collaboration means for us.

I know. Like, it can mean that we produce an event or a campaign or, in contrast, that we invite people with very different value-bases to take part in our panel discussions or experience clubs.

I think being part of a panel is already a form of collaboration. I’d find it very hard to exclude anyone. I think our role should be to allow them to be fucking stupid and then ask a few questions to follow up.

And do you remember what happened with that one National Coalition Party youth member? They wanted to share our posts on social media. Well, I guess it was good promo for them before the elections and everything.

25 June 2020

In a meeting to plan the group’s end-of-year event, Meiju starts an enthusiastic run-through on the plans: The venue has been booked, and a professional production designer has been employed to be in charge of the venue’s decorations. Elli joins to go through the programme: there will be a ‘photobooth-type of Instagram wall’, in front of which people can take photos of themselves with props—mental health-themed speech bubbles with pre-planned hashtags.

One of the major plans for the evening is a mental health-themed panel discussion with local politicians. Meiju introduces this next topic by enthusiastically sharing how the chairperson of the feminist party has already replied how they have ‘gotten to know the group’s activities especially on Instagram and would love to come’. Meiju casually lists how they have invited politicians from the Greens, The Left Alliance, The Social Democratic Party and The Feminist Party. This is obviously clear and agreed upon among the activists but it surprises me. It leaves out close to two-thirds of Finnish parties: not only the populist far right parties but also the often rather moderate right-leaning parties. I ask why they have chosen to limit their invitations as they have. Meiju explains:

Because this is our event, we have stated that we can invite whoever we want. We want to grant visibility for those parties and politicians who share our values. We don’t want someone who does not share them to be able to share on social media that they have been to our event.

November 3rd, 2021

This is indicative of a change in the logic of public action. While civic–rational logic assumes that the orientation of political action is to influence ‘the public opinion’ generated through dialogue in the public sphere, the attention-oriented logic of fame assumes as its object of influence the private opinions of each individual separately (Habermas Citation1991, 219; Botanski and Thévenot Citation2006, 259). The space where opinions and perspectives are formed, then, is not assumed to be the public sphere and a dialogue therein but each individual’s own mind within the confinements of their own home—or rather, behind their own individual screens. Subsequently, the objective of political action changes from fostering a space of dialogue in which common perspectives and agreements can be forged into a space of influencing individual opinions and the individuals’ perceptions of the political actor.

The ability to manage perceptions has consequently become a key skill for political actors and an important marker of their qualifications to serve in public office (Street Citation2004). Inversely, a failure to manage one’s public image is increasingly considered an indicator of an incompetent politician. This logic of valuation was clearly manifest in a recent political scandal in Finland, in which videos of the then prime minister, Sanna Marin, were shared and circulated on social media.

In August 2022, videos of Sanna Marin partying, dancing and twerking with friends were posted on Instagram, quickly followed by a storm of criticism. While parts of the public criticism had a more traditional spearhead—whether ‘this kind of a spectacle’ (see Boltanski and Thévenot 2006, 243) was appropriate behaviour for a leading politician, a woman or a young mother—another strand of critique focused on an entirely different aspect of the matter. These criticisms were not appalled by what PM Marin had done but that we were able to see it. Her poor visibility management was equalled with poor ability to lead a country ().

Sanna Marin had developed a strong international brand, including posing on the cover of the Time magazine (Feb. 17, 2021) and had received numerous other ‘nominations of fame’ in the international press coverage. Unsurprisingly, also the ‘dance gate’ was quickly taken up by international media and social media users. While in Finland, the prime minister was shamed and criticized for the leak, internationally, critical tones quickly became a minority, and an entire movement of support to Marin, to female leaders, to dancing, was formed.

The international support rallied other female leaders posting dance photos of themselves on social media. The mass of powerful women dancing took over Twitter for a few weeks after the initial leaked video and enabled a new framing for the scandal: instead of failed visibility management, the #partygate was now also discussed as a matter of female emancipation. In this framing, the fact that we were able to see the PM dancing was not a lapse of judgement but a deliberate act of female empowerment. The struggle between the two framings boiled ultimately down to a question of the kind of visibility the video was: was it a skilful ‘performance of intimacy’, or a leaked exposé of something that was meant to be kept private?

The scandal around PM Marin indicates an ‘influencerization’ of the power elite and the increasing blurring of boundaries between the roles of a politician and an influencer (Kannasto Citation2021; Pöyry, Reinikainen, and Luoma-Aho Citation2022; Wheeler Citation2012), both of which are trends that sit well with fame-based public valuation. As becomes evident in the #partygate, politicians are increasingly expected to engage in the creation of illusions of proximity and intimacy, characteristic of the fame-based logic of creating followership (Marwick Citation2015; Enli Citation2015). As the powerful and emotive worldwide rally for Marin’s support indicates, the relationship between a politician and their followers resembles one between a celebrity and their fans more than it resembles one between a representative and their constituency (see Street Citation2004). P. David Marshall has termed this ‘the culture of new public intimacy’ (Citation2014), whereby the ability to cultivate and harness emotional ties through the illusion of proximity has come to be considered one of the key abilities of a successful and trustworthy politician in a fame-based democracy.

Furthermore, the means and formats of public action characteristic of an influencer and of a politician in the social media era have become increasingly undistinguishable. Distinct from the role of a celebrity politician under the ‘fame apparatus’ of legacy media, celebrity politicians in the new, social media–driven fame apparatus use the crafting and commodification of their public personas to gain reactions and commitment from their followers (Marshall Citation2020, Citation2021). The influencer/politician is focused on gaining as many supporters and followers as possible and does this by striking a skilful balance between intimacy and publicity: by revealing just enough of their private lives to appear authentic (Enli Citation2015) but not too much to maintain a regal distance and a feel of mystery—a question we will explore next.

Authenticity and civic critique

Another way to approach the prioritizing of fame and public renown is to interrogate the role and meaning of its critique: authenticity (Boltanski and Thévenot 2006, 239). We argue that the meaning of authenticity has changed from signalling a commitment to a free and equal polis to a strategic tool for attaining fame. Subsequently, civic justifications—the (alleged) metacategory of the public sphere—may now have a subversive position. Critique is increasingly assembled by making visible, even parodying, fame-based logic, further indicating its hegemonic position as a megacategory of the public sphere.

Authenticity has traditionally been positioned as the antithesis to the logic of fame (Boltanski and Thévenot 2006, 239; also Banet-Weiser Citation2012). In its early form, as Gaden and Dumitrica (Citation2014) note, authenticity represents an ethic for leading our lives in a way that connects us, as individuals, to the community. Authenticity was ‘to be the guarantor of equality and fairness’ and ‘an ethical system for leading a virtuous and engaged life in a democratic polis’ (ibid.). Authenticity signified the normative ideal of ‘being true to your inner self’ (Trilling Citation1972), and as this could only be achieved in a polis based on equality and freedom, authenticity and democracy as normative ideals became tightly enmeshed.

These civic-oriented definitions of authenticity came to be challenged with the emergence of the mass media, which added a performative element to the concept (e.g. Banet-Weiser Citation2012). In Peterson’s (Citation2005) pre-social media era definition, authenticity is a claim or a performance that can be accepted or rejected by the other. This social constructionist definition moved the civic-based normative concept to one investigating the success or failure of a performance (also Wellman et al. Citation2020; Enli Citation2015)—a move that enabled its later transformation towards a tool in attaining popularity and fame (also Gaden and Dumitrica Citation2014).

Boltanski and Thévenot (2006, 181) note how the ‘price of fame’ is exposure: the requirement to reveal everything so as to appear sincere. Investigating authenticity on social media, Enli (Citation2015) concurs that what is at stake in ‘mediated authenticity performances’ is that one succeeds in appearing authentic to others through, for example, posts that do not seem too pre-calculated or designed (also Faleatua Citation2018). Spontaneity, amateur style of photography, openness about mistakes, and topics from ‘the private realm’ strengthen one’s apparent authenticity on social media (e.g. Wellman et al. Citation2020; Faleatua Citation2018). If an authenticity performance on social media is successful, the spectators buy into the idea that the performance is a genuine and faithful representation of the person posting the content, thus diluting the role and significance of the media platforms between the performer and the spectator (Enli Citation2015).

Paradoxically, and characteristically for the fame-based public sphere, the ability to create a successful and yet popular authenticity illusion has become a craft of its own, requiring particular skills in composing posts that convey spontaneity and a sense ‘from the backstage’ but that nonetheless will ‘go viral’, i.e. meet the algorithmic/cultural demands of appeal and popularity on social media (Wellman et al. Citation2020; Banet-Weiser Citation2012). Dubrofsky (Citation2014) termed this ‘performing not-performing’. In a fame-based public sphere, then, the definition of authenticity has moved from a guarantee of equality or an antithesis of commercial popularity to one of the tools for gaining committed followership (Marwick Citation2015, 139)—tools for attaining fame.

In our examples below, on visual activism on social media and on the street level, we see a battle over the very meaning of authenticity. In them, authenticity is put forward as an argument for allowing everyone the space and possibility to be ‘true to themselves’. At the same time, these portrayals of authenticity operate as ‘strategic performances of authenticity’ (Gaden and Dumitrica Citation2014; Dubrofsky Citation2014)—as tools in gaining attention and support.

Our examples for the play on authenticity come from two distinct sets of fieldwork: one on marginalized young people’s self-images and their political use and another on the French Yellow Vests (YV) movement’s visual claims-making on social media, as well as the street-level visual materiality of their protests. Based on these analyses, we argue that critique through self-making or norm-defying self-imagery was assembled deliberately against fame-based and strongly gendered and classed valuation logic. We argue that if fame-based values did not have a strongly dominant position in the public sphere, images performing authenticity would not be understood as critiques or political acts.

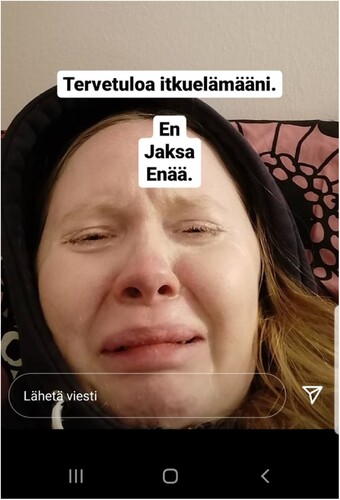

Most young activists in the first fieldwork context recognized the Insta-norm of ‘pretty white homes and never-ending smiles’ they felt was not only limiting but also harmful: ‘toxic positivity’, as Jessika, a mental health activist in her twenties, labelled it. To denounce this, many activists deliberately posted selfies that they knew went against the grain of what was regarded as valuable on Instagram. Jessika made this into something of a trademark of hers, posting a selfie where she cried almost daily ().

Figure 2. Jessika cries in an Instastory posted on her Instagram account. The text says: ‘Welcome to my crying life. I can’t take it anymore.’.

These selfies depicting ‘the imperfection of people’ become politicized in a context where performing perfection and seeking popularity are the norm. On Instagram, tummy fat, hairy armpits and legs, running makeup and sad faces serve as disruptions to the hegemonic valuation structure embedded in social media culture through algorithmic materialisations (see also Hearn Citation2017). The activists we followed used ‘ugly selfies’ to subvert the fame-based valuation logic of social media, crying selfies to tackle its ‘toxic positivity’, played with gender roles to unhinge the fixed gender categories in visual social media, and so on. By appearing differently, the activists suggested something else should be seen as the most valuable, and by so doing, they visually politicized present schemes of valuation, ways of seeing and norms for appearing (see also Tiidenberg and Whelan Citation2017; Meriluoto Citation2023).

Loviisa, a mental health activist, explains:

What matters most to me is that it is real, authentic. I want to broaden what a human being can look like in front of a camera. Not only the shots from ‘the good angle’ you know? — By sharing something authentic, I hope it will give room for other forms of authenticity than the perfectly photogenetic self, or a life where everything needs to be perfect all the time. As a resistance to that demand, you know.

11.9.2020

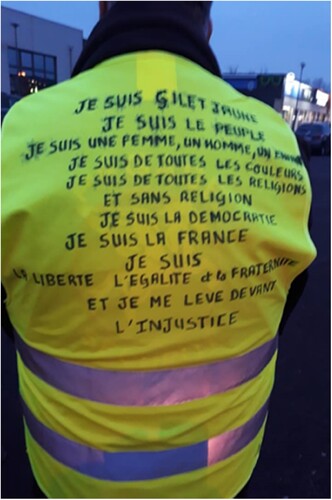

In the case of the Yellow Vests, the visual civic critique was by and large a response to the question ‘who we are’ that was central to the movement’s core message. The local mobilization of people to wear the vest and occupy public spaces was based on a recognition that ordinary, common, disenfranchised, despised people had come together to become visible in a public whose logic of worthiness was based on stylish, educated, upper-middle-class appearances. On the vests, in songs and in conversations, the YV called themselves ‘les gueux’ (the have-nots, the paupers). This ironic self-denomination and a powerful performance of authenticity became visible—in pictures, but also on the street encounters during the protests—through bodies that were rough, unrefined, sometimes fat and shapeless. They were not glamourous, fashionable or ‘cool’ bodies and faces but were often marked by hardship and always by the yellow vest, in itself an important visual marker of the ‘non-remarkable’. The YV aesthetics of ordinariness were also stressed in their social media representations of activists doing unspectacular things and looking like ‘the grey masses’. The visual narrative of the movement included countless scenes of activists hanging out having snacks or drinking coffee in surroundings that did not appear staged—no cool gear, costumes or settings; instead, plastic stools and plain tables.

Such representations can be seen as intended critiques of the assumedly dominant views on who can be a valuable political subject, and the movement participants used the difficulty of the mainstream media to deal with this discrepancy explicitly as a critique. This critique fuelled by authenticity had one of its purest appearances in the vest’s aesthetics. The vests, which recurringly carried the movement’s political messages, often entailed content similar to that in the image below. The text on the vest reads: ‘I am a YV, I am the people, I am a woman, a man, a child, I am of all colours, I am of all religions and without religion, I am the democracy, I am France, I am the Liberty-Egality-Fraternity, and I stand up against injustice.’ ()

In the following section, we discuss the theoretical consequences we suggest the above illustrations entail: what kind of democracy is one based on such fame-centred valuation, and how should we further theorize fame democracy as a manifestation of the plural value base of the public sphere?

Discussion: what does ‘fame-democracy’ look like?

As our illustrations in the previous section show, there are political battles that take shape in the realm of the visual, grounded in questions of who, how and where can appear, in what kind of function, and with what kind of influence or impact. Appearances, visibility and the recognition thereof are undeniably essential features of the current democratic public sphere. The questions that arise from this observation are how, and whether, such non-deliberative features can sustain democracy and whether this kind of public action is non-deliberative to begin with. Are rational dialogue and worded, argumentative and civic deliberation in public the sine qua non of democracy, or what exactly are the interrelations of the deliberative ideal, the public sphere and democracy? What are the defining features of a democracy with a fame-based public sphere? In this section, we suggest a way towards a democracy theory that includes a plurality of arguments and values—even ones that may threaten democracy—as a remedy to the sometimes blinding effect resulting from the normative take on the civic.

‘Fame-democracy’, as a dominating valuation basis for the public sphere, is first and foremost a space of individuals dependent on followers and cheerers. As Boltanski and Thévenot describe in their autopsy of the world of fame, this is an extremely fragile form of greatness. Fame is forgettable: basing greatness on the opinions of others exposes one to instability. Fame needs constant renewal, and it can smash an individual just as it can lift them to (temporary) glory. Fame is brutal in the social media public: besides the algorithmic logic of further emphasizing and enrichening those already in the spotlight, it is also a force of revealing the emperor’s new clothes, or rather, the dozens of layers of the very fakeness it elsewhere promotes. This is not a space for equal debate about anything or fair collective decision-making. It is a space for evaluating means and grounds of visibility as well as questioning and demanding authenticity, even claiming truthfulness. Concretely, it becomes unavoidable for all kinds of political actors to take a stance to the fame-based logic of the social media–driven public sphere: there is no clear-cut separation to be made between the public and the non-public. The democratic public sphere cannot be ‘cleaned’ from un-public or un-civic elements. Paraphrasing Habermas, public life cannot be saved from private content any more than the lifeworld can be saved from colonization. At the same time, even with the algorithms’ and the social media corporations’ tyranny, reaching towards the epicentres of visibility is possible from within the subaltern counterpublics in ways that were unimaginable before.

We have suggested that the quest for maximum visibility overrides the civic virtues of debating between equals and placing the collective before the individual. We have also shown how fame-based public debates can foster civic critique and even how a scandal over fame can have emancipatory side effects. By looking at fame-based claims for authenticity, we have suggested that civic justifications—the alleged metacategory of the public sphere—now have a subversive position. Critique is assembled by making visible, even parodying, fame-based logic and insisting on everyone’s right to be valued for who they are.

Is democracy now increasingly realized in civic critiques of fame-based public discussion? Are civic justifications and democracy, in the end, inseparable? For democracy theory to grasp the realities of the contemporary public sphere, we suggest that it needs to take as a point of departure the inherent and irredeemable differences of human communities, the constant and unavoidable state of conflict resulting from this, and the plurality of valuations that are mobilized from situation to situation to address the conflicts (see Thévenot Citation2015). The pragmatic idea of the plurality of the common good is a ‘realistic’ approach to the public sphere, in the sense Adut suggests, but it is not morally void. This, we argue, is the crucial point normative democracy theories—such as those based on the critique of Habermas we started out with—often miss. Not abandoning civic values but admitting they are one option among the many value bases on which action in the public sphere can be based is the key to creating tools to analyse how democracy in such a public sphere works.

Instead of longing after the normative basis, scholars of democracy should be bolder at touching base with the endless scenarios that value plurality can lead to. We suggest that adhering to the plurality of the common good, which is essential to the theory of justification (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation1991), eventually offers tools to think about a democratic public sphere surviving the greatness of fame and provides concrete ways of approaching the problem empirically (Luhtakallio et al. Citation2024). This seems crucial to also broaden the defence of democracy against threats to it—threats that are very much internal to the current public sphere, undoubtedly have always been so and have never seized to exist by looking the other way. To defend democracy, it seems crucial to be increasingly careful when analysing and using the notion of civic itself. As Paul Lichterman (Citation2020) compellingly shows, ‘the civic’ is conceptually way too blunt to describe what actual practices and actions consist of: in his examples, an advocacy group fighting for equal housing conditions finds itself carrying out a cost–benefit calculation under terms set by a for-profit real estate consultancy firm and, the next hour, planning a street rally to showcase the consequences of housing development projects. These kinds of switching scenes of mundane co-ordinations, much like the ones we have described in this article, open the door to asking what actually is civic and what the relatively blunt definitions thereof may result in. Is the activity civic, no matter what it is, because the people carrying it out define their collective context as ‘civic’? We have argued that much like Lichterman, following the action gives a fuller picture on which to base definitions. In other words, giving up on assuming deliberative, civic principles to rule in a variety of occasions arms us with value-pluralist—and, one might say, more realistic—means to make sense of democracy.

The fame-based public sphere, despite its numerous unfairnesses and shortcomings, helps us see how to theorize democracy more fully. It also allows for new solidarities to form, for instance, through coordinating against the hegemonic conditions of beauty and appeal that can become an explicitly political move to make these conditions explicit and debatable. In hindsight, it looks like the question of equality is increasingly limited to a space of critique of the rules of the game of the public sphere itself—a specific way of coordinating public conflicts. The critiques that draw upon equality now demand equality of fame: ‘We should be equally noticed and recognized’ is the most prevalent form of civic critique under a fame-based public sphere, making it evident that civic critique not only has a subaltern position but operates within a fame-based public culture, with its logic, values and means of coordinating action.

Giving up the civic ideal is not what we suggest as a solution. Instead, we argue that the perspective of a fame-based public sphere enables recognizing that in actually existing democracies, many have given them up and that this creates new kinds of critique and potentially strengthens subaltern counterpublics in unforeseen ways. If addressed realistically, it allows us to see the profound, constantly ongoing value struggles and moral conflicts analytically.

Conclusion

In this article, we hypothesized that the public sphere increasingly operates with fame-based logic. This transforms the political practices of actors who are dependent on wide publicity–social movement activists and politicians alike. The key element of the said transformation is visibility and, alongside it, the (increasing) visuality of political action, often at the expense of worded argumentation or deliberation.

We have discussed the consequences of the above changes to theorizing democracy and the public sphere. The long line of critiques of the Habermasian ideal speech situation and, more recently, Ari Adut’s arguments about the ‘realistic’ conception of the public sphere have paved the way for our propositions. However, it is the theory of justification by Boltanski and Thévenot and their descriptions of the repertoire of valuation based on fame that have helped us develop an understanding of what exactly is at stake in the visual political action we observe taking much space on the ‘public sphere’ as we know it today.

The illustrations based on our empirical examples show that in many different situations concerning political action in public, fame-based logic dominates the strategies taken by the actors. These include features such as stressing visibility over content or emphasizing visibility management as a key capability of a politician. Inversely, the significance of fame becomes discernible in how the meaning of authenticity changes, and ‘authenticity performances’ assume a subversive position. These civic critiques within fame-based logic are made through (self-)irony.

Our argument is that by recognizing the fame-based values that inform public action today with a pragmatist approach, we are able to see a wider variety of action as public action and to interrogate the normative foundations that inform people’s action in public. By focusing on how values are acted upon in the everyday, we are able to develop an understanding of the public sphere that does not need a normative pre-commitment as the basis of its definition. This shift in approach also allows us to think of how democracy could be conceptualized in ways other than through a normative pre-commitment to civic values, enabling us to see other value bases not (only) as a threat to democracy but as an object of inquiry. This may help us move forward in understanding plurality as a key essence of democracy.

Authorship

The authors have contributed equally to this work.

Research ethics

This research has undergone two evaluation processes for research ethics. It has been approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of the Tampere Region (2018), and by the ethics pre-evaluation board of the European Research Council (2019). All research participants have given their written, explicit consent for this research.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the Nordic Sociological Association conference session ‘Politics of Engagement in the Nordic Welfare State’ in Reykjavik, and in the Centre for Sociology of Democracy research seminar at the University of Helsinki. Our warmest thanks to all participants and discussants of these sessions, in particular Veikko Eranti, for their inspiring comments and suggestions. This work is deeply indebted to the ethnographic research conducted by our colleague Karine Clément, and the social media fieldwork and analysis done by our research assistant Minja Sormunen. Our thanks also to the whole ImagiDem team for all their support, and to the reviewers and editors of Distinktion for their constructive criticism and supportive comments, which significantly helped in sharpening the article’s contribution. This article benefited from the peace and space for thinking provided by the Univeristy of Helsinki’s Zoological Research Station in Tvärminne, where most of this article was planned, written and revised. Our final and biggest thanks to all our informants, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The research data of this manuscript are ethnographic, including fieldnotes, interviews, and screenshots of social media posts, taken with explicit consent given to the researcher. As such, the data consist detailed information on research participants, including information that would enable their identification. For this reason, the data cannot be made publicly available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eeva Luhtakallio

Eeva Luhtakallio is Professor of Sociology at the University of Helsinki. She specialises in political sociology, social theory, and sociological methods. Her work focuses on democracy and citizenship as culturally patterned practices, including studies on activism, young people's political engagements and visual politicization. Luhtakallio leads the Centre for Sociology of Democracy (csd.fi) and several research projects, including the ERC funded “Imagining Democracy: Young Europeans becoming citizens by visual participation”.

Taina Meriluoto

Taina Meriluoto is a postdoctoral researcher in sociology at the University of Helsinki, Finland, and a visiting fellow at the University of Essex. She works on (visual) politicization, democratic theory and practice, and focuses especially on the interrelations between the self and political action.

Notes

1 We and our colleague team members (see detail below) have followed the groups presented below, and their consenting individual members with the snap-along ethnographic method (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto Citation2022) between 2019 and 2022. The political scandal data were collected and analysed by the authors and a research assistant during and shortly after its unfolding in 2022, using a method of hashtag ethnography (Bonilla and Rosa Citation2015).

2 For a more detailed illustration of the data and methods, see Luhtakallio and Meriluoto (Citation2022), Luhtakallio, Meriluoto & Malafaia (forthcoming) and Malthezos et al. (Citation2023). For empirical analyses, see, e.g., Malafaia and Meriluoto (Citation2022), Meriluoto (Citation2023).

3 The mental health activist group we followed consists of about 30 active people (women were the vast majority of them) aged between 20 and 35, sharing experiences of mental health problems. The group relies on creative and artistic forms of activism and provides them regular activism training to creatively explore ‘their story’ and communicate their points of view in public. They have a blog, a Facebook page and an active Instagram account. The participants are self-defined ‘digital natives’, using their smartphones and social media habitually. Meriluoto participated in the groups’ meetings (including virtual meetings during the pandemic) and in events they mobilized for while simultaneously following their social media activities and online communications (including Slack, Discord and WhatsApp). Meriluoto also conducted 21 interviews with activists to explore their views on societal participation and social media. The participants were aged between 18 and 35 years, and they all signed informed consent forms prior to the observations and interviews2.

References

- Adut, A. 2012. A theory of the public sphere. Sociological Theory 30, no. 4: 238–62.

- Adut, A. 2018. Reign of appearances: Misery and splendor of the public sphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alexander, J. 2006. The civil sphere. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Allaste, A.A., and K. Tiidenberg. 2015. Sexy selfies of the transitioning self. In Youth cultures, transitions, and generations, eds. D. Woodman, and A. Bennett, 113–26. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137377234_9.

- Arendt, H. 1951. The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Schocken.

- Arendt, H. 1958. The human condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bail, C. 2021. Breaking the social media prism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Baiocchi, G. 2003. Emergent public spheres: Talking politics in participatory governance. American Sociological Review 68: 52–74.

- Baiocchi, G., E.A. Bennett, A. Cordner, P. Klein, and S. Savell. 2014. Civic imagination: Making a difference in American political life. London, NY: Routledge.

- Banet-Weiser, S. 2012. Authentic TM: The politics of ambivalence in a brand culture. New York: NYU Press.

- Bennett, W.L., and A. Segerberg. 2012. The logic of connective action. Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5: 739–768.

- Boltanski, L., and E. Chiapello. 1999. Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme (Vol. 10). Paris: Gallimard.

- Boltanski, L., and L. Thévenot. 1991. De la justification. Les économies de la grandeur. Paris: Gallimard.

- Boltanski, L., and L. Thévenot. 2006 [1991]. On justification: economies of worth. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Bonilla, Y., and J. Rosa. 2015. Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42: 4–17.

- Braudy, L. 1986. The frenzy of renown: Fame and Its history. New York: Vintage.

- Braudy, L. 2011. Knowing the performer from the performance: Fame, celebrity, and literary studies. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 126, no. 4: 1070–5.

- Bruns, A., and T. Highfiel. 2015. Is Habermas on Twitter? Social media and the public sphere. In The Routledge companion to social media and politics, eds. Axel Bruns, Gunn Enli, Eli Skogerbo, Anders Olof Larsson, and Christian Christensen, 56–73. New York: Routledge.

- Caldeira, S.P., S. Van Bauwel, and S. De Ridder. 2021. Everybody needs to post a selfie every once in a while’: Exploring the politics of Instagram curation in young women’s self-representational practices. Information, Communication & Society 24, no. 8: 1073–90.

- Calhoun, C., ed. 1992. Habermas and the public sphere. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Canaday, M. 2003. Promising alliances: The critical feminist theory of Nancy Fraser and Seyla Benhabib. Feminist Review 74, no. 1: 50–69.

- Centemeri, L. 2017. From public participation to place-based resistance. Environmental critique and modes of valuation in the struggles against the expansion of the Malpensa airport. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 42, no. 3: 97–122.

- Dahlberg, L. 2005. The Habermasian public sphere: Taking difference seriously? Theory and Society 34: 111–136.

- Dubrofsky, R. 2014. The hunger games’: Authenticating whiteness and femininity under surveillance. Critical Studies in Media Communication 31, no. 5: 395–409.

- Eliasoph, N. 1998. Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Emirbayer, M., and M. Sheller. 1998. Publics in history. Theory and Society 27, no. 6: 727–79.

- Enli, G. 2015. Trust me, I am authentic!’ authenticity illusions in social media politics. In The Routledge companion to social media and politics, eds. Axel Bruns, Gunn Enli, Eli Skogerbo, Anders Olof Larsson, and Christian Christensen, 121–36. New York: Routledge.

- Eranti, V., and M. Lonkila. 2015. The social significance of the Facebook like button. First Monday, 20.

- Faleatua, R. 2018. Insta brand me: Playing with notions of authenticity. Continuum 32, no. 6: 721–38.

- Fraser, N. 1990. Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text 25/26: 56–80.

- Fraser, N. 1995. Politics, culture, and the public sphere: Toward a postmodern conception. Social Postmodernism: Beyond Identity Politics 291: 295.

- Fraser, N. 2013. What’s critical about critical theory? In Feminists Read Habermas: Gendering the Subject of Discourse, ed. J. Meehan, 21–55. New York: Routledge.

- Fraser, N. 2014. Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy1. In Between borders, 74–98. Routledge.

- Gaden, G., and D. Dumitrica. 2014. The ‘real deal’: Strategic authenticity, politics and social media. First Monday 20, no. 1, doi:10.5210/fm.v20i1.4985.

- Garnham, N. 2007. Habermas and the public sphere. Global Media and Communication 3, no. 2: 201–14.

- Gerlitz, C., and A. Helmond. 2013. The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive Web. New Media & Society 15, no. 8: 1348–1365.

- Habermas, J. 1991. The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hand, M. 2020. Photography meets social media: Image making and sharing in a continually networked present. In The handbook of photography studies, ed. G. Pasternak, 310–26. London: Routledge.

- Hearn, A. 2017. Verified: Self-presentation, identity management, and selfhood in the age of big data. Popular Communication 15, no. 2: 62–77.

- Jenkins, H., and A. Zimmerman. 2016. By any media necessary: The new youth activism. New York: NYU Press.

- Kannasto, E. 2021. ‘I am horrified by all kinds of persona worship!’ constructing personal brands of politicians on Facebook. Acta Wasaensia 468. Väitöskirja: Vaasan yliopisto.

- Lafaye, C., and L. Thévenot. 1993. Une justification écologique?: Conflits dans l'aménagement de la nature. Revue française de sociologie 34, no. 4: 495–524.

- Lara, M.P., and R. Fine. 2007. Justice and the public sphere: The dynamics of Nancy Fraser’s critical theory. In (Mis) recognition, social inequality and social justice. Nancy Fraser and Pierre Bourdieu, ed. T. Lovell, 48–60. New York: Routledge.

- Lenhart, A. 2015. Youth participation in democratic life: Stories of hope and disillusion. Teen, Social Media and Technology Overview 2015, 133–66.

- Lichterman, P. 2020. How civic action works: fighting for housing in Los Angeles. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Lichterman, P., and N. Eliasoph. 2014. Civic action. American Journal of Sociology 120, no. 3: 798–863.

- Luhtakallio, E., V. Eranti, G. Boldt, M. Jokela, L. Junnilainen, T. Meriluoto, and T. Ylä-Anttila. 2024. Youth participation and democracy: Cultures of doing society. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Luhtakallio, E., and T. Meriluoto. 2022. Snap-along ethnography: Studying visual politicization in the social media age. Ethnography, online first, July 2022.

- Luhtakallio, E., T. Meriluoto, and C. Malafaia. 2023. Visual politicization and youth challenges to an unequal public sphere: Conceptual and methodological perspectives. In The handbook on youth activism, ed. Jerusha Conner. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar (in press).

- Luhtakallio, E., and T. Ylä-Anttila. 2023. Justifications analysis. In Handbook of economics and sociology of conventions, eds. Rainer Diaz-Bone, and Guillemette de Larquier. New York: Springer.

- Malafaia, C., and T. Meriluoto. 2022. Making a deal with the devil? Portuguese and Finnish activists’ everyday negotiations on the value of social media. Social Movement Studies, 1–17.

- Malthezos, V., E. Luhtakallio, and T. Meriluoto. 2023. Ethnography-trained Deep Learning: Methodological Approach to Understanding Visual Political Action. In review.

- Mansbridge, J. 2017. The long life of Nancy Fraser’s ‘rethinking the public sphere’. Feminism, Capitalism, and Critique: Essays in Honor of Nancy Fraser, 101–18.

- Marshall, P.D. 2014. Celebrity and power: Fame in contemporary culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Marshall, P.D. 2020. Celebrity, politics, and new media: An essay on the implications of pandemic fame and persona. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 33: 89–104.

- Marshall, P.D. 2021. The commodified celebrity-self: Industrialized agency and the contemporary attention economy. Popular Communication 19, no. 3: 164–77.

- Marwick, A.E. 2015. Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture 27, no. 1: 137–60.

- McClure, C.S. 2014. War, madness, and death: The paradox of honor in Hobbes’s Leviathan. The Journal of Politics 76, no. 1: 114–125.

- Meriluoto, T. 2023. The self in selfies—Conceptualizing the selfie-coordination of marginalized youth with sociology of engagements. The British Journal of Sociology 74, no. 4: 638–56.

- Merten, L., N. Metoui, M. Makhortykh, D. Trilling, and J. Moeller. 2022. News won’t find me? Exploring inequalities in social media news use with tracking data. International Journal of Communication 16: 1127–1147.

- Milan, S. 2015. When algorithms shape collective action: Social media and the dynamics of cloud protesting. Social Media + Society 1, no. 2.

- Oliver, P.E., and D.J. Myers. 1999. How events enter the public sphere: Conflict, location, and sponsorship in local newspaper coverage of public events. American Journal of Sociology 105: 38–87.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2002. The virtual sphere. The internet as a public sphere. New Media & Society 4, no. 1: 9–27.

- Peterson, R. 2005. In search of authenticity. Journal of Management Studies 42, no. 5: 1083–98.

- Pöyry, E., H. Reinikainen, and V. Luoma-Aho. 2022. The role of social media influencers in public health communication: Case COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Strategic Communication 16, no. 3: 469–84.

- Reed, I.A. 2013. Power: Relational, discursive, and performative dimensions. Sociological Theory 31, no. 3: 193–218.

- Ricoeur, P. 1995. Le Juste. Paris: Editions Esprit.

- Rhodes, S.C. 2022. Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and fake news. Political Communication 39, no. 1: 1–22.

- Rousseau, J-J. 1980 [1762]. The social contract. London: Penguin books.

- Russmann, U., and J. Svensson. 2017. Interaction on Instagram?: Glimpses from the 2014 Swedish elections. International Journal of E-Politics 8, no. 1: 50–65.

- Schudson, M. 1992. Was there ever a public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In Habermas and the public sphere, ed. C. Caloun, 143–63. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Senft, T. 2013. Microcelebrity and the branded self. In In A companion to New media dynamics, eds. John Hartley, Jean Burgess, and Axel Bruns, 346–54. Malden, MA: Wiley.

- Street, J. 2004. Celebrity politicians: popular culture and political representation. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 6, no. 4: 435–52.

- Swidler, A. 1986. Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review 51, no. 2: 273–86.

- Tiidenberg, K., and A. Whelan. 2017. Sick bunnies and pocket dumps: ‘Not-selfies’ and the genre of self-representation. Popular Communication 15, no. 2: 141–53.

- Thévenot, L. 2015. Making commonality in the plural, on the basis of binding engagements. In Social bonds as freedom: Revising the dichotomy of the universal and the particular, eds. P. Dumouchel, and R. Gotoh, 82–108. New York: Berghahn.

- Trilling, L. 1972. Sincerity and authenticity. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Van Dijck, J. 2013. You have one identity’: Performing the self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media, Culture & Society 35, no. 2: 199–215.

- Wellman, M.L. 2022. Black squares for black lives? Performative allyship as credibility maintenance for social media influencers on Instagram. Social Media + Society 8, no. 1.

- Wellman, M.L., R. Stoldt, M. Tully, and B. Ekdale. 2020. Ethics of authenticity: Social media influencers and the production of sponsored content. Journal of Media Ethics 35, no. 2: 68–82.

- Wheeler, M. 2012. The democratic worth of celebrity politics in an era of late modernity. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14, no. 3: 407–22.

- Ylä-Anttila, T., and E. Luhtakallio. 2016. Justifications analysis: understanding moral evaluations in public debates”. Tuomas Ylä-Anttila. Sociological Research Online 21, no. 4.