Abstract

The media has a central role in communicating and constructing health knowledge, including communicating research findings related to alcohol consumption. However, research on news reporting about alcohol is still a relatively small field; in particular, there are few studies of the reporting of biomedical alcohol and drug research, despite the assumed increasing popularity of biomedical perspectives in public discourse in general. The present article addresses the representational ‘devices’ used in Swedish press reporting about biomedical alcohol research, drawing on qualitative thematic analysis of the topics, metaphors, and optimist versus critical frames used in presenting biomedical research findings. In general, the press discourse focuses on genetic factors related to alcohol problems, on the role of the brain and the reward system in addiction, and on medication for treating alcohol problems. Metaphors of ‘reconstruction’ and ‘reprograming’ of the reward system are used to describe how the brain’s function is altered in addiction, whereas metaphors of ‘undeserved reward’ and ‘shortcuts’ to pleasure are used to describe alcohol’s effects on the brain. The study indicates that aspects of the Swedish press discourse of biomedical alcohol research invite reductionism, but that this result could be understood from the point of view of both the social organization of reporting and the intersection of reporting, science, and everyday understandings rather than from the point of view of the news articles only. Moreover, some characteristics of the media portrayals leave room for interpretation, calling for research on the meanings ascribed to metaphors of addiction in everyday interaction.

Keywords:

Introduction

Public policy on health issues such as drinking and drug use often relies on the assumption that information about health risks is useful to individuals in their attempts to lead a healthy life (Rose Citation1999). Scientific knowledge is considered central to public information about health risks, but scientific publications use specialized language and methods and can, therefore, be difficult for non-specialists to interpret (Nelkin Citation1995). People who lack direct experience of science largely depend on media reporting for developing an understanding of research findings (Nelkin Citation1995; Dahlstrom Citation2014). For example, according to two recent surveys, Swedish citizens acquire knowledge of scientific findings above all via TV and newspapers (Vetenskap & Allmänhet Citation2015), a majority have high or relatively high confidence in researchers, and medical science enjoys the greatest confidence (Vetenskap & Allmänhet Citation2014). Consequently, the media are crucial in communicating health research to the public, contributing to the social construction of knowledge. Media images of science are an important object of sociological study because this socially constructed knowledge, in turn, is a part in the interpretive processes by which people understand, conceptualize, and act upon their own habits (cf. Hacking Citation2000). Despite the central role of the media in communicating and constructing health knowledge and despite the considerable contribution of alcohol consumption to the global burden of disease (Rehm et al. Citation2009), research on news reporting about alcohol is still a relatively small field (cf. Hansen & Gunter Citation2007) and there are few, if any, studies of the media reporting related to biomedical alcohol and drug research. The current article addresses this issue by analyzing how the Swedish press portrays biomedical alcohol research.

In the Swedish political and treatment contexts, alcohol and drug problems have mainly been conceptualized as social issues, at least since around the 1960s (Edman & Olsson Citation2014). However, medically oriented descriptions have appeared at different points in time, connected to concerns over coercive treatment in the 1970s; the need for an internationally accepted terminology for describing problems in the 1990s; and issues regarding the organization of treatment in the 2010s, respectively (Edman & Olsson Citation2014). Due to Sweden’s recent history of conceptualizing drinking and drug use as social issues, the case of Swedish media reporting may provide interesting and relevant contrasts to other contexts, such as the US, where medical definitions appear to have a stronger footing (e.g. Campbell Citation2011, Citation2012). Furthermore, with medical definitions of addiction currently on the political agenda, Swedish media representations of biomedical alcohol research may play a particularly important role in affecting public knowledge and problem definitions.

The social context of news reporting

Newspapers are produced in a complex context. Media and communications research identifies a number of constraints operating to affect what is eventually published, as only a small selection of the events of the world enter into the news (e.g. van Dijk Citation1988; Strömbäck et al. Citation2012). Material constraints derive from the economy of news production; newspapers are supposed to sell and the audience, in this sense, consists of consumers of media products (Koller & Wodak Citation2008). The social routines of newsgathering and organizational production introduce another set of constraints related, for example, to the periodicity of newspapers and the specialization of journalists in different fields such as crime, politics, or science (van Dijk Citation1988). Further constraints are introduced by unstable forms of employment, time pressures and related processes of editorial selection (Fairclough Citation1995), job stress, and knowledge constraints (Finer et al. Citation1997). Moreover, central values such as novelty and negativity (i.e. reporting about negative events such as crime, disaster, war) are part of the process guiding selection and construction of the news (e.g. van Dijk Citation1988; Schudson Citation2011). Consequently, news are made in social-organizational and cultural contexts. This does not mean that they are artificial products intended to deceive, but that the social-organizational and cultural processes of news production and content need to be taken into account (cf. Schudson Citation1989).

The present article departs from a cultural model for understanding the role of the media in society, where the media ‘establish a web of meanings, and, therefore, a web of presuppositions or background assumptions within which people develop beliefs and viewpoints and in relation to which people live their lives’ (Schudson Citation2011, p. 19). The study does not assume that there is a direct causal relationship between media portrayals and readers’ points of view or ways of acting. The potential causal forces of the news are more complex than what such a model would concede. Generally, research on media effects shows that causal influence lies in a combination of (1) the distribution of information; (2) the legitimacy granted a message through dissemination in general public media; and (3) the framing of the news, which indicates the specific selective perspective(s) of the world that are communicated in ways of presenting and organizing facts and information (Schudson Citation2011). Framing research is an interdisciplinary approach for studying media representations and media influence (Scheufele & Tewksbury Citation2006) with sociological origins in Goffman’s (Citation1974) frame analysis. Sociological versions of framing research set out to study the implicit ways in which the modes of presentation of the news contribute to the social construction of an issue (e.g. Gamson & Modigliani Citation1989; Scheufele & Tewksbury Citation2006; van Gorp Citation2007), often by analyzing large corpora of news (e.g. Gamson & Modigliani Citation1989) and addressing the general ‘media packages’ (Gamson & Modigliani Citation1989; cf. van Gorp Citation2007) latent in reporting on an issue.

Compared with framing research, the present paper analyzes representations of biomedical alcohol research on the microlevel, using an inductive approach to address a smaller corpus of news. This approach is warranted because previous research has focused on broad, general patterns of framing or problem construction by actors other than the media, notably in analyzing how drinking and drug use are constructed as medical or criminal rather than social problems (e.g. Conrad & Schneider Citation1980; Campbell Citation2012; see Netherland Citation2012 for an overview). Medicalization, as it is applied in these previous studies, involves a reductionist approach to social problems due to its sole emphasis on biological causes and its attempts to solve problems by recommending medical treatment, thereby diverting attention away from social causes, contexts, and solutions. While such analyses are important and illuminating of overall societal tendencies, the broad perspective does not allow for a study of tensions and contradictions in media reporting on a particular issue. As McRobbie and Thornton (Citation1995) argued more than 20 years ago, media sociology needs to take the complexity of contemporary media into account and avoid assuming that the media are univocal. Therefore, instead of repeating the medicalization critique, the present article analyzes tendencies of reductionism in the press discourse and investigates the forms of expression of such potential reductionism.

Reductionism can be conceptualized in several ways. In the tradition following Conrad and Schneider (Citation1980), reductionism is implicit in the concept of medicalization itself, as medicalization indicates the extent to which medical perspectives are dominant in explaining, understanding, and treating substance use problems. Studies in this tradition analyze, for example, political documents (e.g. Edman & Olsson Citation2014); scientific publications and scientists’ discourse (e.g. Campbell Citation2012); and press portrayals (e.g. Hellman et al. Citation2015) to identify the perspectives used to frame addiction problems. For example, biological explanations were not found to be predominant in press portrayals of addiction problems in Finland, Italy, Poland, and the Netherlands (Hellman et al. Citation2015). However, in the present article, reductionism is instead conceptualized as the extent to which the media reports of biomedical alcohol research focus on biological factors only. This might seem redundant, as biomedical research by definition should focus on biological factors. Nevertheless, the point of this definition is to enable a distinction between media representations that imply that there are no other relevant perspectives on addiction than the biological (ontological reductionism) and media representations that imply that there are several relevant perspectives (e.g. medical, social, and psychological), but that medical researchers confine themselves to studying biological factors (methodological reductionism). This distinction is pertinent given recent debate on the overall relevance of social and other non-medical perspectives on addiction (e.g. Nature [editorial] Citation2014; Heim et al. Citation2014). Thus, compared with studies of the general media framing of addiction problems (e.g. Hellman et al. Citation2015), the present study addresses how biomedical alcohol research is represented in the Swedish media, instead of analyzing tendencies of medicalization in the overall Swedish media reporting on alcohol.

Media reporting of health research

The scholarly literature on media reporting of health research is wide-ranging and diverse, covering for example media representations of cancer, diabetes, and HIV, as well as media representations of mental illness and the so-called lifestyle or risky behaviors such as smoking and unsafe sex (see Kline Citation2006, for a review). Existing research on media representations of substance use has analyzed the portrayal of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco in teen movies, music videos, and advertising (see Kline Citation2006; cf. Hansen & Gunter Citation2007) and news coverage of specific issues such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (e.g. Connolly-Ahern & Broadway Citation2008). The studies described below are a selection of relevant studies that focus on media representations of biomedical health research on lifestyle behaviors in newspapers.

With regard to the selectivity of information in newspaper reporting, these studies show that journalists are more likely to report on scientific articles that lend themselves to dramatization than on those that do not (Saguy & Almeling Citation2008); that the press tends to highlight research that confirms the existence of a gene for alcoholism at the expense of research that contradicts or disconfirms the existence of such a gene (Conrad Citation1997); and that reporters tend to use quotes from expert interviewees to indicate caution in interpreting the research findings of a study (e.g. ‘it needs to be replicated’; ‘it may be only one part of a larger story’), but seldom quote those who are critical of the scientific validity of the study as a whole (Conrad Citation1999). Correspondingly, Saguy and Almeling (Citation2008) found that the media seldom expressed criticism of the research they were reporting. On the rare occasions when such criticism appeared, it was in reporting on scientific studies that brought up scientific disagreement. Moreover, in a study of US press coverage, Nelkin (Citation1995) found that science was generally portrayed as a series of dramatic events, starting out with great optimism but shifting to criticism and negative reporting when initial promises failed to be fulfilled (see also Conrad Citation2001, on ‘genetic optimism’); that reporting was focused on competition, describing science as a ‘race’ for breakthroughs; and that scientists were not neutral sources of information, but actively sought a favorable press.

Existing research also shows that science reporting of health research frequently involves the use of imagery. Metaphors in science reporting have been the topic of numerous studies, several focusing on the reporting of genetic research (e.g. Nelkin Citation1995, Citation2001; O’Mahony & Schäfer Citation2005; Petersen et al. Citation2005; Hansen Citation2006). According to Nelkin (Citation1995), metaphors in media portrayals of genetics convey ‘simple, condensed, and attention-seeking impressions – a ‘blue-print’ of life, a ‘Book of Man’, a ‘medical crystal ball’’ (Nelkin Citation1995, p. 6). Overall, metaphors are important in science reporting, as aids in explanation but also as devices that convey particular beliefs and worldviews (Lakoff & Johnson Citation1980; Nelkin Citation1995; Semino Citation2008). In relation to alcohol and drugs, the metaphor of ‘the hijacked brain’ – originally developed to explain how alcohol and drugs affect the brain – has been criticized for being used to further demonize drug users (e.g. Hickman Citation2014), despite the intentions of the scholars behind the theory of addiction as a brain disease. Moreover, the ‘hijacked brain’ metaphor contributes to constructing a ‘brain-based’ view of addiction, a perspective that has been discussed and criticized for locating the problem of addiction within the individual (e.g. Campbell Citation2011, Citation2012). Other studies, however, have found that neuroscientific notions of the brain and the self need not be interpreted as reductionist, but may be integrated with social and psychological notions of selfhood (Pickersgill et al. Citation2011) and that biomedical scientists themselves do not necessarily rely on biologically reductionist ontological assumptions with regard to behavior and disease (Pickersgill Citation2009).

To sum up, existing research suggests that potential reductionism in media portrayals can be identified by analyzing representational ‘devices’ (word choice, metaphors, and topics), and metaphors related to the ‘brain-based self’, as well as analyzing selectivity of information and lack of criticism in reporting research findings. Motivated by the lack of prior studies, the current article focuses on the following dimensions of the Swedish newspaper discourse of biomedical alcohol research: (1) the general topics; (2) the use of metaphors and imagery; and (3) the use of optimist versus critical frames for presenting research findings.

Methods

The analytical perspective of the study is qualitative thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke Citation2006), with some elements of content analysis. The paper also draws some methodological inspiration from the framing approach, aiming to identify the representational ‘devices’ in newspaper discourse that convey certain images of alcohol and alcohol problems (cf. Gamson & Modigliani Citation1989).

The material consists of 82 newspaper articles published between 1995 and 2010Footnote1 in four of the largest daily Swedish newspapers (Dagens Nyheter, Svenska Dagbladet, Aftonbladet, and Expressen). Articles that contained one or several of the keywords genes, biomarkers, the brain, chromosomes, DNA, hormones, neurotransmitters, and medication (pharmaceuticals) in combination with a set of keywords representing alcohol, alcohol problems, and addiction were collected from the database Mediearkivet.Footnote2 All article types except readers’ letters were included. The initial search procedure resulted in 273 articles. Because some of the keywords have alternative meanings in Swedish, a first sorting involved excluding articles that were not in fact about biomedical alcohol research. The headlines and leads of the 273 articles were read in their entirety, and the final sample of 82 articles included only articles that had the term ‘alcohol’ (or a closely similar term) and one or more of the keywords used to capture biomedical research either in the headline or in the lead.

Initially, the newspaper material was read and coded inductively. Background codes describing the material (headline; newspaper; date of publication; type of article) and codes describing the content (central words, concepts, metaphors, and lines of argument used; type of research reported; level of detail in description of research; actors and sources quoted; if the reported research referred to gender, class, or ethnicity) were developed in the process of the first reading. In a second step, the coded material was organized into four general topics (healthy lifestyle; genes; the brain and the reward system; and medication). Next, the material was analyzed at the latent level (Braun & Clarke Citation2006), by focusing on style, tone of voice, and type of address, and the meaning(s) assigned to alcohol. Particular importance was attributed to the headlines and lead, as the most important information in the article is presented there (van Dijk Citation1988; Schudson Citation2011).

Results

Four topics were developed to describe the newspaper discourse (). The articles generally describe the body at different levels of detail, conceptualized here as molar (referring to body parts or to the body as a whole) or molecular (referring to factors or processes within the body at a detailed, micro- or molecular level) (cf. Rose Citation2001, Citation2007). The newspaper articles aim to inform the readers, but also to explain and warn or present advice. The purpose of presenting advice and warning readers is most prominent in articles relating to healthy lifestyle, while the purpose of explaining is most prominent in articles relating to genes, the brain and reward system, and medication.

Table 1. Topics and types of story in the newspaper material.

Genes and genetic factors

Genes and genetic factors related to alcohol problems are the main topic of nine articles; these highlight genetic factors in headlines, introduction, and first paragraphs. However, genes are also mentioned in a substantial proportion of the material (34 articles), as a part in explaining, for example, how the reward system works. Three of the nine articles that focus on genes are more detailed in their representations of genetic factors. According to one of these articles, genes are important in producing the MAO enzyme, described as relevant for depression, antisocial behavior, and alcoholism: ‘Two genetic variations that increase the risk for boys to become depressed, antisocial, or alcoholic have the opposite effect on girls. And vice versa. […] A short version of the gene MAO-A for boys and a long version for girls, in combination with a problematic childhood environment, implied, for example, an increased risk of alcohol-related problem behaviors’ (Lutteman Citation2007). The second article reports about a study where researchers ‘have for the first time found an individual gene that has a decisive effect when it comes to becoming drunk from alcohol’, arguing that ‘the gene produces a specific protein, a so-called ion channel that is found on the surface of brain cells’ (Bojs Citation2003; see ). The third article describes a gene responsible for regulating levels of serotonin: ‘Those who were alcoholic and violent tended to have a specific version of exactly the same gene that makes the mice violent. It is a gene that produces a receptor (receiver) for the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain. The neurotransmitter serotonin in particular has been shown to have a decisive importance for mood and impulse control’ (Bojs Citation1998). The articles are both optimistic about genetic research findings, as expressed in wording used to describe research such as ‘revolutionary’, ‘very exciting’, and ‘new’, and as involving a ‘big step forward’, and somewhat more cautious as in ‘Sober worms raise hopes for alcoholism medication’ (Bojs Citation2003). Most of the articles present probabilistic statements about heritability, explaining that heritability ‘stands for about half’ (Bojs Citation2000; Asker Citation2009) and ‘between 50 and 60%’ (Nordgren & Lerner Citation2003) of the risk of developing alcohol problems. Only one article uses the concept of ‘an alcoholism gene’ (Svensson Citation2003). Open criticism of research findings does not appear, but quotes from expert interviewees are used to indicate caution in ways similar to that noted by Conrad (Citation1999); experts ask, for example, ‘is the research in an early stage?’ (Bojs & Lerner Citation2007) and state that ‘there is a long way from research on worms to research on humans’ (Bojs Citation2003). In general, the articles rely heavily on expert interviews and didactic and impersonal address in describing research results.

The brain and the reward system

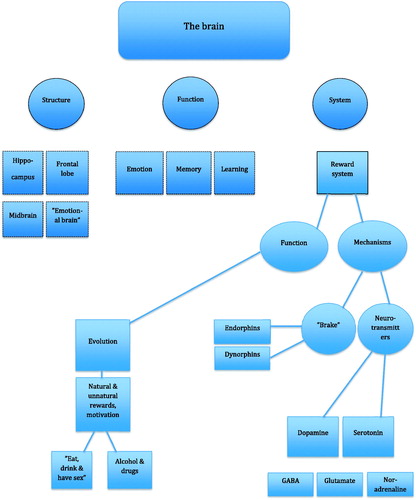

The brain is the main topic of 14 articles, but is mentioned in an additional 51 articles, which renders it at least a status of important background in a majority of articles. Moreover, the brain and the reward system are presented as the main explanatory agents in the newspaper discourse, as indicated in the following quote: ‘No matter how you enter upon this, you end up there [in the reward system], says researcher Jörgen Engel. It is the common, neurobiological denominator; a complex network in the brain.’ (Nordgren Citation2003). As in articles about genes, expert interviews and didactic and impersonal address are standard features.

Metaphors are used to describe how the brain and the reward system work. The metaphors rely on notions of construction (the reward system can be ‘reconstructed’), machinery, mechanics, and electricity (the reward system has ‘pumps’ and ‘brakes’; it can be ‘trimmed’; and it can be ‘short-circuited’) and programing (the reward system can be ‘reprogrammed’). These types of metaphor are common in popular science discourse of the physiological body, with metaphors describing the brain as a computerized system being more recent than metaphors of machinery and construction (Lupton Citation2003; Semino Citation2008). In addition, the metaphor of ‘the reward symphony’, where alcohol is posited as the conductor of a symphony orchestra of neurotransmitters, appears in two articles (Nordgren Citation2003; SvD Citation2005). Metaphors are also used to explain and evaluate the effects of alcohol and drugs as ‘shortcuts’ to pleasure. Six articles locate the reward system in the context of evolution, arguing that ‘natural rewards’ are produced when we ‘eat, drink, and have sex’ (see also Nordgren Citation1996; Bojs Citation1997; Bojs Citation2000; SvD Citation2001; Nordgren Citation2003; Asker Citation2009, ‘sex, eating and physical exercise’) and that alcohol and drugs produce ‘unnatural’ or ‘undeserved’ rewards. The use of the metaphor ‘shortcut’ and the wording ‘undeserved reward’ suggests a subtle moral evaluation of alcohol use; in particular, ‘shortcut’ and ‘undeserved reward’ connote a lack of appropriate achievement in the newspaper discourse:

Alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, amphetamine, and heroin all have one thing in common: they increase the secretion of dopamine in the emotional brain. You could say that they release a sense of reward without us having deserved it. (Bojs Citation1997)

When basic needs such as food, drink, and sex are experienced as pleasurable, the chance is greater that they will be fulfilled and both the individual and the species will survive. ‘We plan our lives to experience these pleasures, but we may also take a shortcut through drugs. They become substitutes for the natural rewards’, says Jörgen Engel. (Lagerblad Citation2001)

Overall, the metaphors and descriptions of the reward system contribute to constructing an image of the brain’s function (mechanics, electricity, information, music); the effects of alcohol and drugs on the brain (’shortcut’, ’unnatural reward’); and, to some extent, a sense of lack of agency for the addicted individual, as indicated in the quote below:

The reward system of the brain motivates us to eat, drink, and procreate. When we engage in these activities, dopamine is released in the reward system; this makes the activities enjoyable and makes us want to repeat them. The dangerous thing is that alcohol often activates the brain's reward system more powerfully than the naturally rewarding behaviors. With excessive use of alcohol, this may lead to a reprograming of the brain, so that it prefers rewards from alcohol. Fully developed dependence involves loss of control; the addict cannot resist the impulse to take the drug. (Asker Citation2009)

The newspaper articles explain by naming structures or regions of the brain and mentioning the general functions of these (left hand part of ), and by naming, and further zooming in on, the reward system (right hand and lower part of ). The reward system, in turn, is explained by describing the biochemical mechanisms thought to be involved in addiction, focusing on neurotransmitters and a ‘brake’ for the reward system, on one hand, and the general function of the reward system for survival, on the other hand. Thus, the articles describe how addiction may be the result of a failing ‘brake’ in the reward system (early articles from 1996 and 2003) or the result of alterations in the levels of several different neurotransmitters (articles from all years). From this micro- or molecular level of abstraction, they shift to the general by describing the function of the reward system in human motivation, arguing that it has developed so as to guarantee our survival by making it pleasurable to eat, drink (not alcohol), and have sex (‘natural rewards’). This is followed by descriptions of how heavy use of alcohol and drugs (‘unnatural rewards’) may lead to ‘reprograming’ or ‘reconstruction’ of the brain and thus result in addiction. The relations between these different levels of abstraction are left unaccounted for, leaving a gap in between the description of the molecular processes of the reward system and the process of human evolution.

Medication

Medication was the most common topic in the material (43 articles). The articles in this category are mainly about Campral (acamprosate) and Revia (naltrexone), approved for sale in Sweden in 1996 and 2000, respectively, but there is also some discussion of other pharmaceuticals (e.g. ondansetron, antidepressants). Most of these articles are comparatively short and rely on, but do not completely reproduce, versions of the consumer information genre, a factual genre that provides straightforward, rational information (Ajagán-Lester et al. Citation2003). The sections that center on information tell readers when ‘the new pill’ will be available for sale in Sweden, how it should be used, and what the side-effects are. Occasionally, the company that sells or manufactures the pill is mentioned, and expert interviews are common. Slightly more than half of the articles (25) describe that the medication ‘takes away the desire to drink’ or ‘reduces the pleasurable effects of alcohol’, whereas the rest (18) mention or explain how the medication affects the brain. In a small number of articles, information is combined with short interviews with well-known personalities who are ‘sober alcoholics’ (e.g. an entertainer, a TV-show host), adding aspects of a human interest story. In all years, article headings are either descriptive (e.g. ‘New medication against alcohol dependence’) or positive of medication (e.g. ‘New pill reduces craving for alcohol’; ‘New pill can cure liquor problems’), while later sections introduce some caution, explaining that medication should be combined with therapy and other forms of support (e.g. psychosocial treatment; self-help groups; advice; cognitive behavioral therapy). One article quotes an interviewee saying ‘For me, this was a miracle pill’ (Bratt Citation2007), but most articles do not use this kind of celebratory language. Given that the large majority of these articles report about new medication, most of them do not discuss treatment of addiction in general, but concentrate on explaining – often very briefly as in the quote below – how the medication affects the brain:

Campral is the name of the pill that may reduce the craving for alcohol. Researchers speak about a breakthrough in the treatment of misusers. The pill is supposed to be combined with conversational therapy. The treatment is suitable for people who are in a socially stable situation but know that their alcohol consumption is high. […] The pill affects the neurotransmitters in the brain and restores processes that have been damaged. It reduces the craving for alcohol, and in addition, the feeling of elation and intoxication is dampened. (Westin Citation1999)

In addition to the three themes discussed above, 16 articles in the material report about everyday health issues. In these articles, categorized under the theme Healthy lifestyle, the biomedical aspects of alcohol’s effects are backgrounded and mainly used to support and provide additional depth to a general description of how alcohol affects health. The focus is on describing drinking practices and situations (e.g. weekend partying, summer holidays, Midsummer’s Eve), not to report about scientific findings or scientific procedures. An overview of the characteristics of these articles is presented in , but as they do not focus on science reporting, they will not be further discussed in the analysis.

Criticism, optimism, and causes of alcohol problems

The extent to which the news articles include criticism of biomedical research findings can also be understood more broadly as implicit in discussion of perspectives other than the biomedical or as implicit in discussion of causes of alcohol problems. Three articles that were not categorized as belonging to any of the main themes (Sidenbladh Citation1995; Sidenbladh Citation1998; Vinterhed Citation2000) relate scientific discussion of the concept of addiction, privileging social perspectives and providing some general criticism of biomedical perspectives. An additional article categorized under the theme Healthy lifestyle presents psychological, social, and biomedical perspectives side-by-side (Lagerblad Citation2001). However, these discussions do not concern specific research findings or studies. With regard to causes of alcohol problems, implicit ‘causal’ statements such as ‘stands for’, ‘gives’, ‘guides’, and ‘governs’, were examined throughout the whole newspaper corpus, showing that genetic factors are mentioned most often in the material (34 articles), but that ‘the environment’ is mentioned occasionally as well (13 articles), as in the quote below:

Heritability stands for about half of the risk of becoming addicted to alcohol. In this case, the risk of developing dependence already in youth is increased. An increased genetic risk of developing dependence is often general. Someone who has addiction in their family often runs a greater risk of being affected. The availability of cheap liquor and drinking habits in the environment has an effect as well. The interplay between inheritance and environment decides who is affected. Moving to a country where alcohol is cheap, having many opportunities to drink, and lacking the disciplining effect of an occupational life may be one trigger, difficulties in life another. (Asker Citation2009)

About half of the 13 articles do not specify what ‘the environment’ refers to, but those that do, briefly mention childhood, family environment, or upbringing (six articles), availability of alcohol (four articles), ‘social environment’ (two articles), and drinking habits (one article). Thus, multifactorial causes of alcohol problems are implied in a minority of articles.

Discussion

This paper focused on the representational ‘devices’ used in media reporting of biomedical alcohol research and the extent to which these contribute to tendencies of biological reductionism. While biomedical research by definition should focus on biological factors, it was argued that the media representations of this research may still be more or less reductionist and that potential reductionism may be expressed in different ways. The analysis of topics, metaphors, and word choice; causes of drinking problems; and selectivity of information, presents a mixed view. Heritability has an important, but not all-encompassing and monolithic position as cause in the press discourse; genetic causes are presented from a probabilistic rather than deterministic perspective; and the idea of a single gene for alcoholism only appears in one article. Medication is described in positive terms, but is generally not conceptualized as a magic bullet, and it is underlined that medicines should be combined with psychosocial treatment. ‘Environmental factors’ as (partly relevant) ‘causes’ of drinking problems; the probabilistic approach to genetics; and the approach underlining that medication should be combined with psychosocial treatment, point towards a kind of methodological, rather than ontological, reductionism. Nevertheless, the newspaper discourse also exhibits a lack of criticism of biomedical research findings; very few news articles present multiple perspectives or sides of the issue; and no articles criticize specific research results (but a few present general critiques of biomedical perspectives and some include cautionary expert quotes). The descriptive metaphors of the brain and the reward system are to some extent compatible with the ‘brain-based’ view of addiction, while word choice and metaphors used to discuss alcohol’s effects on the brain draw on everyday life connotations (‘undeserved’ reward; ‘shortcuts’ to pleasure). In this way, biological reductionism is most clearly present in the focus on genetic causes, the lack of criticism and multiple perspectives, and possibly, but not necessarily, in the use of metaphors to describe alcohol’s effects on the brain.

According to Lakoff and Johnson (Citation1980), metaphors have the capacity to affect what we perceive, how we think, and how we act in certain contexts. The descriptive metaphors of the brain are neither unusual (cf. Lupton Citation2003; Semino Citation2008) nor necessarily new or propelled specifically by biomedical addiction research (cf. Vidal Citation2009; Pickersgill Citation2013), but are they reductionist? Metaphors related to the ‘brain-based self’ locate agency within the brain. While the ‘hijacked brain’ metaphor does not appear in the Swedish press discourse, the use of descriptive metaphors of reconstruction and reprograming suggest, to some extent, that the agency of the addicted person resides in the brain. Yet, the meaning of these descriptive metaphors is less clear. It has been argued that they invite a reductionist view of addiction as an individual and medical–biological problem (e.g. Campbell Citation2011), but as other research implies (e.g. Pickersgill Citation2009; Pickersgill et al. Citation2011), such a view is not inherent in concepts or metaphors themselves. Therefore, metaphors should also be understood from the perspective of how they are interpreted. In other words, metaphors are reductionist if interpreted as though the addicted person is governed by their brain (to the exclusion of the social situation and context). In the study by Pickersgill et al. (Citation2011), research participants discussing neuroscience did not understand the brain as completely dominant of selfhood; instead, neuroscientific concepts were mixed with pre-existing, mundane notions of subjectivity. Similarly, a study of newspaper readers’ interpretations of one of the newspaper articles included in this analysis (Alcohol short-circuits important part of the brain; Carlsson Citation2006) shows that readers integrate and mix their own everyday perspectives with the biomedical concepts used in the news article. Newspaper readers relied on an everyday ‘reward for performance’ logic when interpreting the notion of the reward system, where reward implied rewarding oneself with a substance (e.g. alcohol) either to encourage oneself when feeling low or to reward oneself for work or study achievements (Winter Citation2016). Both these studies indicate that metaphors used to describe brain function are not necessarily interpreted in a unified way or as implying a completely reductionist view of selfhood and agency. Furthermore, metaphors are important because they can be used in various ways in social and interactional contexts ‘outside’ newspaper discourse. Within the Swedish newspaper discourse, the descriptive metaphors are generally coupled with arguments in favor of providing treatment and assistance to misusers; the scientists interviewed underline that there is a need to reduce the blame attached to addicted individuals. In relation to the moral issue of responsibility, metaphors that suggest a lack of agency or willpower by locating agency in the brain can be used to account for and legitimize various ways of acting (cf. Scott & Lyman Citation1968), depending on the social status and position of the actor and the social and interactional context where the metaphors are employed. For example, metaphors may be used as excuses for behavior that others disapprove of or they may be used by politicians and policy-makers, treatment professionals, and others in the field, to legitimate treatment or punishment (cf. Reinarman Citation2005). The notions and metaphors used to describe the effects of alcohol and drugs in the newspaper discourse – ‘undeserved reward’ and ‘shortcuts’ to pleasure – can also be understood from the perspective of their everyday connotations. However, these involve not only a descriptive but a moral-evaluative dimension as well. In particular, they invite interpretations emphasizing a lack of achievement on the part of the individual, who appears to try to avoid the hard work required to produce ‘deserved’ reward. Word choice and metaphors used to describe alcohol’s effects on the brain in the Swedish press discourse are, therefore, more open to interpretations that blame the addicted person than metaphors used to describe brain function as such. As noted above, the scientists interviewed in the Swedish press are opposed to blaming the individual, but given the role of individual blame in justifying punitive sanctions against misusers, for example in the US (Reinarman Citation2005), an important task for future research is to study how notions such as ‘shortcut’ and ‘undeserved reward’ are interpreted and used by politicians and treatment professionals in the addiction field.

Furthermore, the newspaper articles on genes and the brain and reward system do not present explicit advice and recommendations to the readers, but leave courses of action implicit and inherent in the information and explanations presented. This way of presenting research results provides more space for readers to draw their own conclusions and calls for an understanding of the processes through which this happens. Moreover, the explanations generally leave a gap between the biomedical-molecular level, which focuses on mechanisms involved in the brain’s response to alcohol, and the evolutionary level, which focuses on the role of the reward system in survival, opening up for varying mechanism-based as well as functionalist interpretations of addiction.

Finally, parts of the reductionist pattern in reporting can also be understood from the point of view of the social-organizational context of the news. The specialization of science – researchers possessing different knowledge and expertise – has consequences for science reporting, as it relies heavily on expert sources (Nelkin Citation1995; Conrad Citation1999); experts are not expected to address and explain theories and perspectives outside their own field in any detail. In this way, the lack of (detailed) explanations focusing on social factors in news articles about biomedical research would be a consequence of scientific specialization. Reporting could be balanced by including several perspectives in the same article, but organizational and economic pressures limit the extent to which this is possible. As Conrad (Citation1999) argues, while journalists are supposed to provide balanced accounts, the journalists he interviewed generally saw this task as related to overall reporting and not necessarily relevant to each single article. The organization of news reporting also suggests that there is not enough space to present several perspectives in the same article (Conrad Citation1999). From this perspective, it becomes reasonable to report biomedical research in one article, and social research in another, and thereby potentially achieve balance in the long run. In reporting, finally, the lack of criticism of the validity of scientific findings may be understood as a consequence of journalists’ trust in the peer-review system of elite scientific journals, but also as a consequence of editorial selection; if a news article would include serious criticism of the reported research findings, the news value of the story might be questioned and the article not published (Conrad Citation1999).

To conclude, this study indicates that the Swedish press discourse of biomedical alcohol research exhibits certain reductionist tendencies, but that these could be understood from the point of view of both the social organization of reporting and the cultural meanings created through the intersection of reporting, science, and everyday understandings, rather than from the point of view of the news articles in isolation. While aspects of the media discourse invite reductionism, other aspects leave room for interpretation, and call for research on the meanings ascribed to metaphors of addiction in everyday interaction.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Anders Ledberg for valuable comments on previous versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

The author reports that she has no conflicts of interests.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, 10.13039/501100001861 [Grant 2010-0989].

Notes

1 The year 1995 was chosen for strategic and practical reasons; first, biomedical addiction research started to gain increasing media attention around the middle of the 1990s (Midanik & Room Citation2005); second, 1995 is the first year when all the four newspapers are indexed in Mediearkivet.

2 The search terms were all in Swedish, and were translated into English in preparing this paper.

References

- Ajagán-Lester L, Ledin P, Rahm H. 2003. Intertextualiteter. In: Englund B, Ledin, P, editors. Teoretiska perspektiv på sakprosa. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Agrawal R, Allamani A, Arvers P, Beccaria F, Berridge V, Blomqvist J, Boniface S, Bruno R, Buchanan J, Bühringer G, et al. 2014. Addiction: not just brain malfunction. Nature. 507:40. doi: 10.1038/507040e.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3:77–101.

- Campbell N. 2011. The metapharmacology of the ‘Addicted Brain’. J History Present. 1:194–218.

- Campbell N. 2012. Medicalization and biomedicalization: does the diseasing of addiction fit the frame? In: Netherland J, editor. Critical perspectives on addiction. Netherland: Emerald Publishing; p. 3–25.

- Connolly-Ahern C, Broadway SC. 2008. To booze or not to booze? Newspaper coverage of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Sci Commun. 29:362–385.

- Conrad P. 1997. Public eyes and private genes: historical frames, news constructions, and social problems. Soc Prob. 44:139–154.

- Conrad P. 1999. Uses of expertise: sources, quotes and voice in the reporting of genetics in the news. Public Understand Sci. 8:285–302.

- Conrad P. 2001. Genetic optimism: framing genes and mental illness in the news. Cult Med Psychiatry. 25:225–247.

- Conrad P, Schneider J. 1980. Deviance and medicalization: from badness to sickness. St. Louis: Mosby.

- Dahlstrom M. 2014. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 111(Suppl 4):13614–13620.

- Edman J, Olsson B. 2014. The Swedish drug problem: conceptual understanding and problem handling, 1839–2011. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 31:503–526.

- Fairclough N. 1995. Media discourse. London & New York: Bloomsbury.

- Finer D, Tomson G, Björkman N-M. 1997. Ally, advocate, analyst, agenda-setter? Positions and perceptions of Swedish medical journalists. Patient Educ Couns. 30:71–81.

- Gamson W, Modigliani A. 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am J Sociol. 95:1–37.

- Goffman E. 1974. Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Hacking I. 2000. The social construction of what ? Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hansen A. 2006. Tampering with nature: ‘Nature’ and ‘the natural’ in media coverage of genetics and biotechnology. Media Cult Soc. 28:811–834.

- Hansen A, Gunter B. 2007. Constructing public and political discourse on alcohol issues: towards a framework for analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 42:150–157.

- Hellman M, Majamäki M, Rolando S, Bujalski M, Lemmens P. 2015. What causes addiction problems? Environmental, biological, and constitutional explanations in press portrayals from four European welfare societies. Subst Use Misuse. 50:419–438.

- Hickman T. 2014. Target America: visual culture, neuroimaging, and the ‘hijacked brain’ theory of addiction. Past Present. 222 (Suppl 9):207–226.

- Kline K. 2006. A decade of research on health content in the media: the focus on health challenges and sociocultural context and attendant informational and ideological problems. J Health Commun. 11:43–59.

- Koller V, Wodak R. 2008. Introduction: shifting boundaries and emergent public spheres. In: Ruth Wodak, Veronika Koller, editors. Handbook of communication in the public sphere. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; p. 1–17.

- Lakoff G, Johnson M. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lupton D. 2003. Medicine as culture: illness, disease and the body in Western societies. New York: Sage.

- McRobbie A, Thornton S. 1995. Rethinking moral panic for multi-mediated social worlds. Br J Sociol. 46:559–574.

- Midanik L, Room R. 2005. Contributions of social science to the alcohol field in an era of biomedicalization. Soc Sci Med. 60:1107–1116.

- Nature. 2014. Animal farm [editorial]. Nature. 506:5.

- Nelkin D. 1995; rev ed. Selling science: how the press covers science and technology? New York: WH Freeman & Co.

- Nelkin D. 2001. Molecular metaphors: the gene in popular discourse. Nat Rev Genet. 2:555–559.

- Netherland J. 2012. Introduction: sociology and the shifting landscape of addiction. In: Critical perspectives on addiction. Bingley: Emerald Publishing; p. xi–xxv.

- O’Mahony P, Schäfer M. 2005. The ‘Book of Life’ in the press: comparing German and Irish media discourse on human genome research. Soc Stud Sci. 35:99–130.

- Petersen A, Anderson A, Allan S. 2005. Science fiction/science fact: medical genetics in news stories. New Genet Soc. 24:337–353.

- Pickersgill M. 2009. Between soma and society: neuroscience and the ontology of psychopathy. Biosocieties. 4:45–60.

- Pickersgill M. 2013. The social life of the brain: neuroscience in society. Curr Sociol. 61:322–340.

- Pickersgill M, Cunningham-Burley S, Martin P. 2011. Constituting neurologic subjects: neuroscience, subjectivity and the mundane significance of the brain. Subjectivity. 4:346–365.

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. 2009. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 373:2223–2233.

- Reinarman C. 2005. Addiction as accomplishment: the discursive construction of disease. Addict Res Theory. 13:307–320.

- Rose N. 1999. Governing the soul. 2nd ed. London: Free Association Books.

- Rose N. 2001. The politics of life itself. Theory Cult Soc. 18:1–30.

- Rose N. 2007. Molecular politics, somatic ethics and the spirit of biocapital. Soc Theory Health. 5:3–29.

- Saguy A, Almeling R. 2008. Fat in the fire: science, the news media and ‘the obesity epidemic’. Sociol Forum. 23:53–83.

- Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. 2006. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 57:9–20.

- Schudson M. 1989. The sociology of news production. Media Cult Soc. 11:263–282.

- Schudson M. 2011. The sociology of news. 2nd ed. London: Norton.

- Semino E. 2008. Metaphor in discourse. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Scott M, Lyman S. 1968. Accounts. Am Sociol Rev. 33:46–62.

- Strömbäck J, Karlsson M, Hopmann DN. 2012. Determinants of news content: comparing journalists’ perceptions of the normative and actual impact of different event properties when deciding what’s news. J Stud. 13:718–728.

- Van Dijk T. 1988. News as discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Van Gorp B. 2007. The constructionist approach to framing: bringing culture back in. J Commun. 57:60–78.

- Vetenskap & Allmänhet. 2014. Fusk och förtroende: Om mediers forskningsrapportering och förtroendet för forskning. VA-report 2014:3. Stockholm: Vetenskap & Allmänhet.

- Vetenskap & Allmänhet. 2015. VA-barometern 2015/16. VA-report 2015:6. Stockholm: Vetenskap & Allmänhet.

- Vidal F. 2009. Brainhood, anthropological figure of modernity. Hist Hum Sci. 22:5–36.

- Winter K. 2016. Coproduction of scientific addiction knowledge in everyday discourse. Contemporary Drug Problems. 43:25–46.

Newspaper articles

- Asker A. (2009) ‘How is alcoholism treated?’ Svenska Dagbladet, September 1, 2009.

- Bojs K. (1997) “Drugs give a sense of reward”. Dagens Nyheter, September 7, 1997.

- Bojs K. (1998) “Hereditary connection alcoholism – violence: Newfound gene”. Dagens Nyheter, November 17, 1998.

- Björk R. (1999) “Sun, wind – and alcohol”. Expressen July 26, 1999.

- Bojs K. (2000) “There are different types of alcoholics”. Dagens Nyheter, December 2, 2000.

- Bojs K. (2003) “Sober worms raise hopes for alcoholism medication”. Dagens Nyheter, December 14, 2003.

- Bojs K, Lerner T. (2007) “Genetic test can find the right alcohol medication & Medication takes away the craving for alcohol”. Dagens Nyheter, February 18, 2007.

- Bratt A. (2007) “Epilepsy medication can help alcoholic”. Dagens Nyheter, October 28, 2007.

- Carlsson L. (2006) “Alcohol short-circuits important part of the brain”. Svenska Dagbladet, March 5, 2006.

- Johansson A. (2010) “Drink smarter – feel better”. Dagens Nyheter, January 31, 2010.

- Lagerblad A. (2001) “Intoxication – a quick ticket to feeling”. Svenska Dagbladet, January 2, 2001.

- Lundberg B. (2001) “New alarming report on why alcohol is more dangerous to women”. Expressen, May 17, 2001.

- Lutteman M. (2007) “Bad gene for men is good for women”. Svenska Dagbladet, February 8, 2007.

- Nordgren M. (1996). “Reward systems: The inner brake governs your drinking”. Dagens Nyheter, December 10, 1996.

- Nordgren M. (2003) “Alcohol: A drink to the reward symphony”. Dagens Nyheter, April 14, 2003.

- Nordgren M, Lerner T. (2003) “Alcohol: Mother and son follow the same tracks”. Dagens Nyheter, April 17, 2003.

- Sidenbladh E. (1995) “The anatomy of the misuser.” Svenska Dagbladet, November 15, 1995.

- Sidenbladh E. (1998) “You don’t do anything you do not want to”. Svenska Dagbladet, April 23, 1998.

- SvD (2005) “Alcohol problems may give smaller brain lobe” (no author). Svenska Dagbladet September 17, 2005.

- SvD (2001) “Researcher receives million grant for studies of alcohol dependence” (no author). Svenska Dagbladet, February 20, 2001).

- Svensson G. (2003) “Research on worms can cure alcohol misuse”. Aftonbladet, December 12, 2003.

- Westin K. (1999) “New pill can reduce the craving for liquor”. Expressen, January 7, 1999.

- Vinterhed K. (2000) “Availability creates misuse”. Dagens Nyheter, April 2, 2000.