Abstract

Introduction and aims: The high prevalence of women experiencing co-occurring substance use, interpersonal abuse, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has led to international calls for trauma-specific substance use treatments and wider trauma-informed practice. The aim of this study was to explore how services in England have developed practice responses with limited historical precedence for this work.

Design and Methods: A purposive sample of 14 practitioners from substance use, interpersonal violence and criminal justice services were chosen for their integrated practice. Semi-structured interviews exploring their understanding of the co-occurring issues, staged treatment models and wider trauma-informed practice, and the challenges associated with this. Thematic analysis was employed.

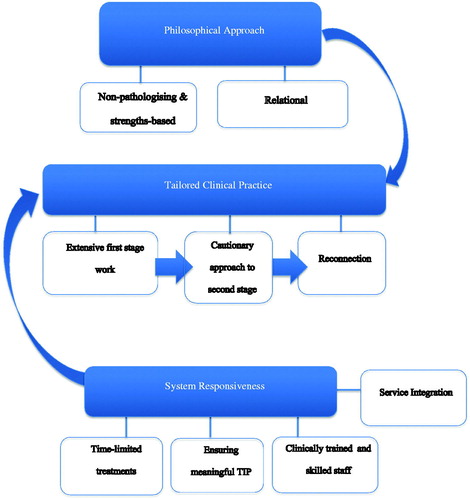

Results: Three key interlinking themes were identified: practitioners’ philosophical approach; tailored clinical practice, and system responsiveness. Analyses identified the importance of relational, non-pathologising practice, extensive focus on physical and emotional safety, and cautionary approaches towards using trauma-specific treatments involving trauma disclosure. Challenges included poor service integration, time-limited treatments and tokenistic trauma informed practice.

Discussion: Practitioners from across disciplines emulated important components of trauma-informed practice and promoted a ‘safety-first’ approach reliant on multi-agency working and wider system responses. Trauma-specific interventions required skilled and experienced practitioners, and longer treatment programmes comprising first stage work.

Conclusions: In the context of limited gender-responsive substance use treatment in the UK, practitioners demonstrated integrated practice that supported the recommended staged PTSD model and trauma-informed practice. Organisational leadership and support from service commissioners and funders are recommended to promote growth of this approach across the UK.

Introduction

The ubiquity of interpersonal abuse (IPA) [defined here as physical, emotional or sexual violence/abuse in adulthood or childhood] experienced by women who use substances (40–70%) must be acknowledged and addressed if treatment for this population is to be effective (El-Bassel et al. Citation2005; Gutierres and Van Puymbroeck Citation2006). Whilst an estimated 30–59% of women receiving substance use treatment have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Najavits Citation2002), many will go undiagnosed, and some will show symptoms indistinguishable from PTSD despite not meeting the diagnostic criteria (Hien Citation2009). Symptoms include re-experiencing trauma, self-blame, negative affect, hyper-arousal, and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). People with sub-threshold symptoms have also reported higher levels of functional impairment, risk of suicidality, and substance use compared to non-PTSD samples (Brancu et al. Citation2016).

Experiencing prolonged and repeated IPA such as child abuse and domestic violence is correlated with increased prevalence of both substance use and PTSD (Rees et al. Citation2011) and may result in Complex PTSD with additional symptoms such as alterations in emotional regulation, belief systems, relations with others, and dissociation (Herman Citation2001). Substance use by IPA victims may also increase victimisation as they may be less likely to risk assess and implement safety planning (Iverson et al. Citation2013). Ongoing risks of abuse may then interfere with substance use treatment, requiring a greater focus on safety within treatment (Galvani Citation2006). These interrelated factors bring added complexity to providing effective treatment for women and require responses that address substance use, IPA, and PTSD symptoms in an integrated way, rather than treating each issue in a silo.

Trauma-specific substance use interventions are focussed on treating trauma and substance use in an integrated manner through therapeutic interventions involving practitioners who have received specialist training in PTSD and substance use. Experts agree the gold standard for delivering such work, particularly for those with Complex PTSD, is the staged treatment model (Herman Citation2001; Najavits Citation2002; Cloitre et al. Citation2011) comprising broadly: (1) Safety and Stabilisation (e.g. building therapeutic relationships, psycho-education of substance use and IPA/PTSD, coping skills, physical safety); (2) Memory Processing (e.g. addressing traumatic memories); and (3) Reconnection (establishing future identity). Crucially, movement through these stages may not be linear and must reflect individual needs. In Australia and the US, clinical PTSD guidelines recommend such approaches (Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health Citation2013; US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and the Department of Defence (DoD) Citation2017). In the UK, clinical guidance now recommends that those with substance use are not excluded from trauma-specific treatments (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Citation2018). However, until recently, the guidance promoted a sequential model where substance use disorders were to be addressed first (NICE Citation2005, Citation2015); this may explain why specialist trauma-specific treatments are currently inaccessible to the majority of those with active substance use. A recent systematic review of psychological treatments to concurrently address PTSD and substance use disorder found some evidence for interventions involving second stage components [e.g. Trauma-Focussed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, TF-CBT (Ehlers and Clark Citation2000)], but only when accompanied by numerous first stage safety and stabilisation services (Roberts et al. Citation2016). However, descriptions of these services were lacking, their suitability for women facing ongoing victimisation unclear, and dropout was high.

The promotion of ‘trauma-informed practice’ (TIP) (US Department of Health and Human Services Citation2014; Mills Citation2015) is another response gaining traction within substance use and other health care services internationally. TIP is a wider organisational approach, based around five core principles: trauma awareness, safety, trustworthiness, choice and collaboration, and building of strengths and skills (Elliott et al. Citation2005). Within the context of substance use treatment, TIP assumes IPA experiences are widespread and provides practitioners with a framework to avoid re-traumatisation, promote physical safety, and use strengths-based practice such as motivational interviewing. This present-focussed approach does not require trauma disclosure nor rely on diagnoses. Some argue that it is only within the context of TIP that trauma-specific treatments should be delivered (Fallot and Harris Citation2005; Mills Citation2015). UK substance use treatment guidelines promote TIP as core business (UK Department of Health Citation2017), however little is yet known regarding the practical adoption of this approach in England.

TIP and first stage trauma-specific treatments are highly congruent; emphasising relationships, establishing safety, and building strengths and skills. Developing the capacity of substance use treatment services to deliver this work is important because it provides a first line response to women with a variety of PTSD symptoms who would be ineligible for other services due to their substance use. In the UK, illustration and evaluation of practitioner experiences of trauma-specific interventions and TIP is sorely lacking. Therefore, this study explored, in-depth, how practitioners from a range of clinical disciplines in England are addressing substance use, IPA, and symptoms of PTSD in their practice with women. Specifically, how are practitioners operationalising TIP and the staged trauma treatment model, and what are the key considerations and challenges faced? This learning will be of interest to practitioners in many countries where trauma work of any type with women who use substances is uncommon, the concept of TIP not widespread, and specialised treatments addressing the co-occurring issues are rare.

Method

This report followed the CORE-Q qualitative research checklist to aid reporting (Tong et al. Citation2007).

Design

This qualitative study involved 14 semi-structured interviews with practitioners from substance use, IPA, and women’s specialist criminal justice services in England.

Sample selection

Practitioners in England working with women experiencing substance use, IPA,and a wide range of PTSD symptoms (full/partial, undiagnosed/diagnosed) were invited to participate in the research via online networks/listservs (n = 9), through gatekeepers in relevant agencies (e.g. Public Health England, academic institutions) (n = 6), and through the researchers’ own contacts (n = 12) (see for inclusion/exclusion criteria). Of the 46 replies from the scoping emails, a number were immediately ineligible (e.g. based in other countries) or did not reply upon follow-up (n = 8), and communication took place with the remaining others (n = 24) to ascertain eligibility. Fourteen practitioners were then purposively selected to reflect a range of expertise, clinical disciplines and service delivery models in England. Most of the 14 practitioners worked in the third-sector sector, and half were clinical psychologists (). Half of the practitioners offered trauma-specific group-work addressing wider mental health issues including PTSD and five only offered 1:1 therapy.

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria used for recruiting the interview sample.

Table 2. Final sample of practitioners interviewed.

Data collection

Ethics approval was received from Kings College London (ref HR-16/17-4598); South London and Maudsley (ref LRS-15/16-1921) and Camden and Islington (ref 204083) NHS Foundation Trusts. Practitioners were sent an information sheet in advance explaining informed consent, confidentiality, and data protection. Written informed consent was obtained before commencing all interviews. A topic guide was used to interview practitioners once by KB as part of her PhD, either at stakeholder services or the University; interviews were conducted between February-November 2016 and lasted between 50 and 80 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by KB. Unique identification numbers were assigned to all data and person identifiable data removed from transcripts.

The topic guide asked practitioners about their motivations for undertaking work to address substance use, IPA, and PTSD symptoms; practice models; familiarisation with trauma-specific interventions and TIP; change mechanisms, and challenges to their work. The topic guide drew on principles of realist interviewing (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997), which allows the researcher to put forward their own theories about subject matter and invite interviewees to challenge, reject, or refine such theories. Some of the theories proposed and discussed included the self-medication theory (Khantzian Citation1997); ongoing victimisation impacts treatment engagement; and IPA requires different responses to other forms of trauma. So, whilst there is a collaborative approach to theory development, the method is realist at heart, in that the interview is searching for evidence of ‘real phenomena and processes’ (Maxwell Citation2012), based on the experiences and views of experienced practitioners. This approach also provided opportunity for the interviewer (KB) to better expose her positionality; a feminist researcher whose extensive experience working in the domestic violence sector, and interviewing survivors of IPA, has guided her theoretical perspectives related to the topic matter.

Data analysis

NVivo 10 was used to manage the data. Data were analysed using thematic analysis (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006) encompassing a pragmatic approach moving back and forth between inductive and deductive reasoning (Ritchie and Lewis Citation2003). KB devised an initial broad codebook deductively based on the topic guide (e.g. challenges, TIP, service user profile) and theoretical concepts in staged treatment models. These were applied to segments of text selected as representative of the codes. Through re-reading transcripts, inductive codes were assigned to segments of text representing new themes; some representing smaller coding units of the pre-assigned codes and others unrelated. Four transcripts (28%) were independently coded by a second researcher (KT or GG) and cross-referenced with KB’s codebook; at least 80% of the codes of the second researchers matched those of KBs. Any discrepancies were discussed leading to code revision or the creation of new codes e.g. mental health awareness.

Codes were then merged, pruned and theme creation explored by grouping codes using maps and diagrams, before collating under themes and sub-themes. Coded data were then inspected to check the proposed code/theme groupings were representative of the initial data. Similarities and differences emerging among transcripts were examined to explore relations to clinical discipline/service specialisms. This final stage also underwent several iterations in collaboration with KT and GG.

Results

All practitioners supported women with a range of substance use severity, IPA, and PTSD symptoms. The majority described working with women with suspected full or partial PTSD symptoms but who had not been diagnosed. Whilst the language of TIP was not used widely, the operationalisation of some components were visible. Staged treatment models were most commonly advanced by psychologists, however, all practitioners described core elements of their practice that were highly complementary with this model. Analysis of responses identified three interlinking themes: tailored practice focussed on safety and stabilisation, underpinned by practitioners’ philosophical approach, and a lack of wider system responsiveness. These, along with their subthemes, are represented in and described below.

Figure 1. Thematic mapping relating to practitioner experiences of supporting women with histories of substance use, interpersonal abuse, and symptoms of PTSD.

Philosophical approach

Regardless of clinical discipline or service specialism, all practitioners eschewed the traditional medical model focussed on women’s deficits and pathology in favour of a strengths-based and relational approach.

Non-pathologising and strength-based responses

Several practitioners spoke explicitly about the importance of reframing mental health symptoms and substance use as understandable responses to traumatic experiences. This was an important part of strengths-based practice and focussed on women’s internal resources and resilience to manage the impacts of abuse. Most supported the proposed theoretical framework related to self-medication; the use of substances to cope with PTSD symptoms and the wider stresses of IPA. Several psychologists rejected the use of diagnostic labels:

“For PTSD I don’t even like the ‘D’ because actually you are getting into those diagnoses, it’s actually post-traumatic stress, because that makes sense rather than giving that ‘D’ because with that you are saying its abnormal. But actually, it’s quite normal to experience that.” (04, Psychologist, Third-sector, Substance Use).

Several practitioners challenged the idea proposed in the interview that women experiencing ongoing victimisation are less able to engage in treatment. Instead the problem was reframed in terms of poor service responsiveness, in that services were not set up to address the challenges women face in accessing treatment. For example, most practitioners described how abusive partners sabotage treatment engagement and erode women’s sense of self-efficacy. However, non-attendance or compliance with treatment may be blamed on a woman’s lack of commitment or readiness for change, rather than identified as a barrier that services should address.

Relational approaches

Practitioners described practices that offered choice, flexibility, and facilitated women’s agency; key components of TIP. For many this approach was imperative to building strong therapeutic alliances:

“It’s really important to me that our service is really responsive, it’s important to the staff, they will do their utmost to respond to people as they present…The key point is how people make a relationship with their keyworker, it’s all relational isn’t it?” (05, Service Director, Third-sector, Substance Use)

Many practitioners based in the third-sector felt strongly that their approach was much better suited to working with women facing multiple disadvantage, in comparison to statutory mental health services. The difference appeared to centre on the role of advocacy:

“Within the NHS, within a clinical team… you are not gonna get your clinicians that are going to pick up the phone and advocate for you but actually in the third-sector sector we do quite a lot of that.” (04, Psychologist, Third-sector, Substance Use)

The practitioners based in the third-sector were also more likely to be based in organisations specifically set up to provide services to women, and where the need for advocacy is viewed as central to the formation of trusting relationships with clients.

Tailored clinical practice

The philosophical approach described above drove the service responses of the practitioners. The majority offered trauma-specific interventions, often in group-work, covering topics such as anger, self-esteem, relationships, and compassion. Some of those trained as psychologists also discussed using 1:1 second stage trauma-specific treatments focussing on trauma disclosure.

Extensive first stage work

Regardless of clinical disciplines, sector, or service specialisms, all practitioners used the language of ‘safety’ and ‘stabilisation’ to describe the core components of their work. These are also central concepts in the first phase of the staged trauma treatment model. All practitioners stressed the lengthy and complex process of promoting internal and external safety when working with this cohort of women, particularly when faced with ongoing safety risks:

“I don’t know if it’s because of the duality of alcohol and substance misuse and domestic abuse…but it takes a lot the work regarding safety.” (01, DV Worker, Third-sector, Substance Use)

Safety planning was conceived by many as an important first line intervention preceding therapeutic work:

“If you don’t identify risk outside, it’s impossible to work inside and what’s safe…I can work with her around safety planning needs, she probably has learnt her own safety planning mechanisms, but really it does take talking through them, what are they, so they are also ingrained. Then giving options.” (04, Psychologist, Third-sector, Substance Use)

Helping women to identify and reinforce their own self-established safety strategies, whilst identifying alternatives, is strengths-based practice in action. Providing psycho-education about the theory of self-medication was also further evidence of strengths-based practice and another crucial treatment component. Practitioners with more formal clinical training described the importance of educating women on trauma neurobiology and how their coping strategies may be counter-productive:

“If someone is using alcohol to knock themselves out at night to stop the memories to stop the nightmares, we have to quickly tell people … the way alcohol works on the Central Nervous System…so the very thing that the client thinks is helping them, is maintaining the PTSD symptoms and the sense of current threat.” (11, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use)

Several practitioners, most notably in the IPA services, highlighted the importance of providing information on prevalence and tactics of abusers in order to redress the internalisation of responsibility, blame, and shame. Practitioners described a range of cognitive, behavioural, and body-based techniques to help women achieve stabilisation in regulating emotions, managing symptoms and substance cravings. Many services offered complimentary therapies and mindfulness as part of their standard service. However not all practitioners specifically framed these as PTSD specific interventions, despite the growing evidence base for their effectiveness . This practitioner explains why body-work is important to address IPA:

“We can’t forget that fact that most experiences of violence actually involve an attack on the body so we if we don’t really heal the body, we will miss that.” (06, Service Director, Third-sector, DSV)

Practitioners talked about the positive impact of such techniques in reducing substance use, providing evidence for both the self-medication theory and the promotion of substance use stabilisation for enhancing safety planning within unsafe relationships:

“If you can bring them back to that phase of stabilisation they will be able to use the safety plan.” (04, Psychologist, Third-sector, Substance Use.)

Some practitioners also spoke about the effectiveness of group-work:

“I found that the groupwork was much more effective at leading to change, in terms of symptom management, and the women being able to come to terms with why they were behaving the way they were, because the constant I heard from women was that I am crazy, there is something wrong with me, I can’t control myself, and being able to have those connections, I found those very powerful.” (12, Psychologist, CIC, CJS)

Group-work was identified as useful for delivering first-stage interventions, although some felt that individual therapy may be required first before women could feel safe in a group environment. Those running groups for trauma survivors with substance use advocated a focus on emotional regulation skills avoiding the trauma narrative:

“We do use the words, tools, self-care, those kinds of things, so we deal with the emotions… but not going into the story, that will be with your individual counselling.” (10, Senior Counsellor, Third-sector, Substance Use/Child Sexual Abuse)

Cautionary approach to second stage work

Several practitioners, qualified psychotherapists or psychologists, offered 1:1 trauma-specific treatments incorporating second stage work to reprocess intrusive memories, for example TF-CBT (Ehlers and Clark Citation2000). However, all were very clear about the need for tailored approaches and caution when delivering these treatments. This did not necessarily require full abstinence from substances but required extended preparation involving the first stage worked described above. All practitioners were clear that it is unsafe to do memory processing with women still being re-traumatised:

“I wouldn’t be doing any work on intrusive events at that stage… another metaphor that I use is about the house being on fire and we have to put the fire out first before we start rebuilding.” (09, Psychologist, Third-sector, DSV)

However, caution was also warranted for women who were no longer at risk due to the context in which the IPA was experienced. This highlights how interventions must be tailored to the specific circumstances of individuals:

“She is now doing the memory work, but that has taken 25 sessions… we couldn’t move forward…because she was still living in the flat, where she was raped, so we had to deal with those trigger experiences, it would have been unsafe and unethical to have taken her to the memory work.” (11, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use)

Reconnection

All practitioners also discussed the importance of activities to support women’s transition from a world schema based on their sense of self as ‘mad or bad’ to one of positive self-identity rooted in a healthy social community. Once again, this was not always explicitly recognised as treatment for PTSD but formed part of the standard service package offered. However, in essence this approach mirrors ‘reconnection’ found in later phases of more formal staged trauma treatment:

“We try to reflect aspects of treatment that are pro-social and create networks for women, communal meals, partnership dance project, phase two activities about women moving on and accessing education in the community or volunteering.” (05, Service Director, Third-sector, Substance Use.)

System responsiveness

Clinical practice does not operate in isolation, and practitioners discussed systemic issues that facilitated or challenged their ability to deliver their work.

Service integration

Almost all practitioners highlighted systemic problems within their own, and others’, service-delivery models. When services and the wider system were not formulated on the philosophical approach promoted above, referral pathways were blocked and services became inaccessible to women with co-occurring issues:

“The system is not set up to work with the women…mental health services saying ‘she needs to be stable’ and drug and alcohol services saying ‘we can’t stabilise her cause it’s her mental health’. And then domestic violence services saying ‘she has never engaged with substance misuse or mental health services so we can’t engage with her’’ (02, Complex Needs Worker, Third-sector, DSV)

For this client base, if services fail to understand substance use as self-medication for trauma, then substance use treatment may become ineffective:

“If they have PTSD as well, what’s going to happen if you potentially treat the alcohol abuse through detox and rehab … you are going to get a resurgence of the PTSD, and that could absolutely cause a relapse that ends their detox, it’s a waste of funding, waste of the clients’ time.” (11, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use).

Because of the siloed approach to treating the co-occurring issues within the health and social care system, all practitioners identified the importance of multi-agency working, particularly in terms of establishing physical safety and supporting therapeutic work. Those based in the statutory sector extolled the virtues of multi-agency partners to pick up the role of advocacy, corroborating the assertions of third sector practitioners who believed advocacy was central to relational practice:

“That was crucial in the intervention, that Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference referral, and working with the Independent Domestic Violence Advisor. They were great cause they could do things that I couldn’t do, go around there to see her.” (13, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use)

Time-limited treatments

Several practitioners raised the issue of funding cuts resulting in the commissioning of time-limited substance use treatments. This resulted in a revolving door syndrome of women constantly in and out of services, often returning only when in crisis. Practitioners also critiqued the lengthy waiting lists for mental health services and their inaccessibility for those in early recovery:

“They [community mental health team] will not see someone who has not been abstinent for 3 months, even if they do see someone there is a 6-month waiting list after an assessment.” (11, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use)

Ensuring meaningful TIP

Several practitioners critiqued attempts by their own or other services for attempting to develop TIP that was ‘tokenistic’. Several expressed frustrations of delivering trauma-specific interventions within an environment that had not fully embraced TIP:

“It also includes an organisational philosophy, it’s not just learning a little bit about trauma, and saying ‘you are trauma informed’… I don’t believe a short course in being trauma informed is good enough. I do think it has to be a real foundation.” (08, Psychologist, Third-sector, DSV)

The presence of psychologists operating in substance use and other specialist services for women appeared to be a key driver for embedding TIP organisational change and maintaining staff professional development:

“It works because we have psychologists there, and so I can create that narrative and keep it going with evidence, if you don’t have that regulation in the system or governance in the system, I don’t know how you create trauma informed services.” (11, Psychologist, NHS Mental Health, Substance Use)

Clinically trained and skilled staff

Whilst most practitioners agreed the importance of having skilled staff to deliver more trauma-specific interventions such as group-work, some advocated that only clinical psychologists should be doing this work. Others stressed that clinical qualifications were not always sufficient, emphasising the importance of understanding therapeutic group processes, trauma re-enactment, as well as practitioner self-reflection:

“You really need the skills to understand the process of trauma, be aware of your own biases, and working with women. How do you feel about women who remain in abusive relationships? Do you have your own trauma? Cause if you do then that better be worked on.” (12, Psychologist, CIC, Criminal Justice)

All the practitioners interviewed, regardless of clinical qualifications, had extensive experience working with traumatised women, and had received training on the co-occurring issues. They demonstrated an understanding of the complexities of the subject matter which informed their philosophical approach to service delivery.

Discussion

Practitioners in this study were purposively selected for their attempts to deliver interventions and services to women that address the co-occurring issues of IPA, substance use, and PTSD symptoms in an integrated manner. Unfortunately, such practice remains limited in the UK. For example in substance use services, it is estimated that just under half of local authorities in England provide any form of gender-specific substance use services for women (Agenda and Against Violence and Abuse Citation2017);3 the most common being weekly women-only groups within mixed-gender services (34%) and/or employment of substance use midwives (34%). Practitioners in this study had developed their models despite the lack of clear clinical and government guidance at the time, nonetheless, their practice was closely aligned to the ‘gold standard’ staged model for PTSD treatment (Herman Citation2001; Najavits Citation2002; Cloitre et al. Citation2011). The literature suggests that PTSD treatments aimed at those with a diagnosed substance use disorder are only effective when accompanied by numerous services aimed at the first stage safety and stabilisation work (Roberts et al. Citation2016). There is further suggestion that substance use treatments addressing IPA are effective for substance use reduction among women reporting IPA in the preceding 6 months before treatment entry, compared to women reporting less recent trauma (Fowler and Faulkner Citation2011). As such this sample of practitioners, although not exhaustive of those providing trauma-specific substance use treatments to women in England, could be considered promising practice as the UK embarks in developing more integrated approaches to treating substance use and PTSD.

The recently revised UK clinical PTSD guidelines now encourage clinicians to focus on “the safety and stability of a person’s personal circumstances” as well as addressing barriers which may prevent people from accessing trauma-specific treatments, such as substance use (NICE Citation2018). It remains to be seen how this will be realised in practice. For example, services could choose to adopt a parallel-treatment model that sees the two conditions targeted by professionals in their respective treatment systems at the same time. This is a model that is currently adopted in UK community mental health services for those with severe mental health problems, following the implementation of “Care Programme Approach” policy in 1991 (NICE Citation2016). This policy no longer recommends dual diagnosis workers, but rather the assessment, coordination, and delivery of care for people with severe mental health problems is managed by a key worker in community mental health services (Kingdon Citation1994). This policy was meant to ensure successful co-ordination of care via input from various relevant services, including for example substance use services, but in practice this is often not the case (Simpson et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, organisational TIP in UK mental health services remains elusive (Sweeney and Taggart Citation2018).

This study has illustrated how services in the substance use and women’s specialist sectors can address failings in current practice by working together to deliver integrated substance use and PTSD treatment by means of first stage safety and stabilisation work. This could prepare the groundwork for further second-stage treatment in mental health services if required. This approach may be all the more important given the lengthy waiting lists in mental health services and where the newer second stage trauma-specific substance use treatments available in other countries only comprise a few sessions of safety and stabilisation work (Roberts et al. Citation2016).

In order to do this, organisational leadership is needed to develop meaningful TIP; the framework within which trauma-specific treatments best operate (Harris and Fallot Citation2001; Mills Citation2015). Substance use services, the majority of which are mixed-gender, will require a culture shift that embraces the philosophical approach identified in this study. That is to say, one that recognises the impact of IPA and is non-pathologising, strengths-based, and centred on ‘growth-fostering relationships.’ These are core components of treatment long since promoted by advocates of gender responsive addiction treatment (Covington Citation2000), TIP (Fallot and Harris Citation2005; Mills Citation2015), and integrated trauma-specific treatments aimed at women (Bailey et al. Citation2019).

Pre-dominant in this study was the amount of practitioner time and effort required to support clients to establish physical safety, due to the complex interplay of substance use with PTSD symptoms and IPA, particularly when faced with ongoing victimisation. Practitioners descriptions of women’s partners jeopardising treatment attendance and women’s attempts to stay sober echo findings in the literature (Galvani Citation2006; Gutierres and Van Puymbroeck Citation2006). Women using substances are also at risk of repeated sexual violence by men in their drug-using circles or when involved in prostitution (Teets Citation1997; Gilchrist et al. Citation2005). In order to respond to this, ‘putting out the fire’ requires emphasis on risk management, advocacy and multi-agency working (Itzin et al. Citation2010). Other research has shown that the provision of safe housing (Fallot and Harris Citation2005) and crisis management relating to safety concerns (Foa et al. Citation2013) appears to play a crucial role in women’s ability to benefit from trauma-specific interventions which integrate substance use.

‘Putting out the fire’ also extends to internal safety; supporting women to manage emotional regulation, substance use cravings, and other PTSD symptoms. Many of the IPA and substance use services offered interventions to address the mind-body connection, such as mindfulness and alternative therapies, as part of their standard service. These are now increasingly recognised as important first stage interventions in the treatment of PTSD (Van der Kolk Citation2014).

Both the framework of TIP and first stage work with anyone experiencing PTSD avoids discussion of individual trauma experiences. Practitioners in this study cautioned against group-work that may encourage women to discuss their IPA experiences in detail. Therefore carefully designed programmes that keep the focus on the present-day impacts of trauma in the context of substance use are encouraged (Covington Citation2000; Najavits Citation2002; Fallot and Harris Citation2005). These provide the space to explore the concept of both internal and external safety from multi-focal perspectives and avoid triggering emotional responses which may risk increased substance use.

A pre-requisite for the delivery of more trauma-specific interventions is investment in trained staff with extensive experience working with trauma survivors and groups (Marel et al. Citation2016; Tompkins and Neale Citation2016). Such staff could also address barriers commonly identified in instigating organisational TIP within substance use treatment such as trauma training, continual professional development, and supervision (Blakey and Bowers Citation2014). There is a strong body of international TIP practice guidance and fidelity checklists (US Department of Health and Human Services Citation2014) to facilitate organisational development to ensure TIP is meaningful and safe, particularly when considering the development of trauma-specific interventions.

Limitations to this study relate to sampling and interview method. Attempts were made to select practitioners from multiple sectors who used a variety of pre-existing and/or newly developed programmes. At least two contact attempts were made to all those expressing interest, however some substance use treatment services were unavailable for interview. Nevertheless, whilst theme saturation was not the basis for the selection of the sample, after completing 14 interviews, limited new codes were generated and no new overarching themes established. Many participants felt comfortable disagreeing with the theories proposed by the researcher, suggesting that the methodological approach was not inherently biased. This research has several strengths. It is the first to shed light on how practitioners from a range of services in England are attempting to address women’s experiences of, IPA, substance use and PTSD symptoms. Credibility, in terms of trustworthiness and plausibility, was demonstrated by providing a variety of participant quotes and the context in which they were said, with attempts to highlight minority views. The high inter-rater reliability achieved helped to guard against individual researcher bias.

In the context of limited gender-responsive substance use treatment in the UK, practitioners demonstrated integrated practice that supported the recommended staged PTSD model and trauma-informed practice. Key themes revolved around the extensive focus on safety and stabilisation needed when delivering trauma-specific substance use treatments; a practice model that was challenging to realise when services are commissioned to deliver short-term treatments. Organisational culture shifts were identified as necessary to develop meaningful TIP. Service commissioners and funders can support services by recognising the need for training and development initiatives and longer-term interventions for those with trauma experiences and substance use.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2016. Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services (NICE Guideline NG58).

- Agenda and Against, Violence and Abuse. 2017. Mapping the Maze: Services for Women Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage in England and Wales.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-V). Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association.

- Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Health. 2013. Australian guidelines for the treatment of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. www.clinicalguidelines.gov.au

- Bailey K, Trevillion K, Gilchrist G. 2019. What works for whom and why: a narrative systematic review of interventions for reducing post-traumatic stress disorder and problematic substance use among women with experiences of interpersonal violence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 99:88–103.

- Blakey JM, Bowers PH. 2014. Barriers to integrated treatment of substance abuse and trauma among women. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 14(3):250–272.

- Brancu M, Mann-Wrobel M, Beckham JC, Wagner HR, Elliott A, Robbins AT, Wong M, Berchuck AE, Runnals JJ. 2016. Subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analytic review of DSM-IV prevalence and a proposed DSM-5 approach to measurement. Psychol Trauma. 8(2):222–232.

- Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL. 2011. Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J Traum Stress. 24(6):615–627.

- Covington SS. 2000. Helping women recover. Alcohol Treat Q. 18(3):99–111.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. 2000. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 38(4):319–345.

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. 2005. Relationship between drug abuse and intimate partner violence; a longitudinal study among women receiving methadone. Am J Public Health. 95(3):465–470.

- Elliott DE, Bjelajac P, Fallot RD, Markoff LS, Reed BG. 2005. Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. J Community Psychol. 33(4):461–477.

- Fallot RD, Harris M. 2005. Integrated trauma services teams for women survivors with alcohol and other drug problems and co-occurring mental disorders. Alcoh Treat Q. 22(3-4):181–199.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. 2006. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 5(1):1–11.

- Foa EB, Yusko DA, McLean CP, Suvak MK, Bux DA, Oslin D, O’Brien CP, Imms P, Riggs DS, Volpicelli J. 2013. Concurrent naltrexone and prolonged exposure therapy for patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 310(5):488–495.

- Fowler DN, Faulkner M. 2011. Interventions targeting substance abuse among women survivors of intimate partner abuse: A meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 41(4):386–398. DOI:10.1016/j.jsat.2011.06.001

- Galvani S. 2006. Safety first? The impact of domestic abuse on women’s treatment experience. J Subst Use. 11(6):395–407.

- Gilchrist G, Gruer L, Atkinson J. 2005. Comparison of drug use and psychiatric morbidity between prostitute and non-prostitute female drug users in Glasgow, Scotland. Addict Behav. 30(5):1019–1023.

- Gutierres SE, Van Puymbroeck C. 2006. Childhood and adult violence in the lives of women who misuse substances. Aggress Violent Behav. 11(5):497–513.

- Harris M, Fallot RD. 2001. Designing trauma-informed addictions services. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 2001(89):57–73. DOI:10.1002/yd.23320018907

- Herman J. 2001. Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violence from domestic abuse to political terror. London (UK): Pandora.

- Hien D. 2009. Trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and addiction among women. In: Brady KT, Back SE, Greenfield SF, editors. Women and addiction: a comprehensive handbook. New York (NY): Guildford Press; p. 242–256.

- Itzin C, Taket A, Barter-Godfrey S. 2010. Domestic and sexual violence and abuse: findings from a Delphi expert consultation on therapeutic and treatment interventions with victims, survivors and abusers, children, adolescents, and adults. Melbourne (Australia): Deakin University.

- Iverson K, Litwack S, Pineles S, Suvak M, Vaughn R, Resick P. 2013. Predictors of intimate partner violence revictimization: The relative impact of distinct PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and coping strategies. J Trauma Stress. 26(1):102–110.

- Khantzian E. 1997. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 4(5):231–244.

- Kingdon D. 1994. Care Programme Approach: recent government policy and legislation. Psychiatr Bull. 18(2):68–70.

- Marel C, Mills K, Kingston R, Gournay K, Deady M, Kay-Lambkin F, Baker A, Teeson M. 2016. Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings. Sydney, Australia: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

- Maxwell J. 2012. A realist approach for qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mills K. L. 2015. The importance of providing trauma-informed care in alcohol and other drug services. Drug Alcohol Rev. 34(3):231–233.

- Najavits LM. 2002. Seeking safety. A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. New York (NY): Guildford Press.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2005. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): management. Clinical Guideline CG26. London (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [accessed 2018 Aug 28]. www.nice.org.uk/CG026NICEguideline

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015. Surveillance Review Decsion of CG26 Post-traumatic stress disorder: The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. NICE Centre for Clinical Practice – Surveillance Programme, 2015. [accessed 2018 Aug 28]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg26/evidence

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018. Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE Guideline NG116). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/resources/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-pdf-66141601777861

- National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (NTA). 2006. Models of care for the treatment of adult drug misusers: update 2006. London (UK): NTA.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. 1997. Realistic evaluation. London (UK): Sage

- Rees S, Silove D, Chey T, Ivancie L, Steel Z, Creamer M, Teesson M, Bryant R, McFarlane AC, Mills KL, et al. 2011. Lifetime prevalence of gender based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. J Am Med Assoc. 306(5):513–521.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. 2003. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London (UK): SAGE.

- Roberts NP, Roberts PA, Jones N, Bisson JI. 2016. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD010204.

- Simpson A, Miller C, Bowers L. 2009. The history of the care programme approach in England: where did it go wrong? J Ment Health. 10(5):489–504.

- Sweeney A, Taggart D. 2018. (Mis)understanding trauma-informed approaches in mental health. J Ment Health. 27(5):383–387.

- Teets JM. 1997. The incidence and experience of rape among chemically dependent women. J Psychoactive Drugs. 29(4):331–336.

- Tompkins CNE, Neale J. 2016. Delivering trauma-informed treatment in a women-only residential rehabilitation service: qualitative study. Drugs: Edu Prev Pol 25(1):9.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Healthc. 19(6):349–357.

- UK Department of Health. 2017. Clinical guidelines on drug use and dependence update 2017 Independent Expert Working Group. Drug use and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. London (UK): Department of Health. [accessed 2018 Apr 11]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drug-misuse-and-dependence-uk-guidelines-on-clinical-management

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAHMSA). 2014. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) (Series 57). Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-57-Trauma-Informed-Care-in-Behavioral-Health-Services/SMA14-4816

- US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and the Department of Defense (DoD). 2017. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal012418.pdf

- Van der Kolk B. 2014. The body keeps the score: mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma. London (UK): Allen Lane.