Abstract

Introduction: Premature drop-out and lack of success from alcohol treatment is common. Within recent years, Shared Decision Making (SDM) has gained increased attention in treatment planning in health care. Results from research in SDM in addiction treatment points in different directions, hence this review focuses on alcohol addiction only. Furthermore, studies on Informed Choice is included in this review. The objective is to measure outcome results on the following four measures: (1) drinking outcome, (2) quality of life, (3) enrollment, and (4) adherence.

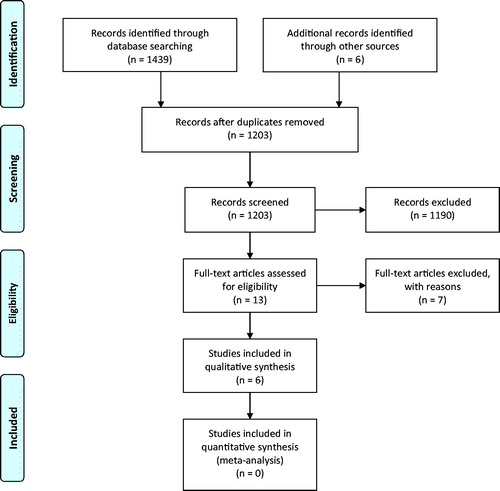

Method: MEDLINE, PubMed and PsychInfo databases were searched. Studies included were RCT or Quasi-RCT measuring SDM or informed choice in treatment planning in alcohol addiction. The PRISMA guidelines was followed. Two researchers measured the quality of the studies. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, a third researcher was consulted.

Results: 1203 studies were identified. Thirteen met the inclusion criteria, of which 7 were excluded. The remaining 6 studies were too heterogeneous to perform a meta-analysis, resulting in a narrative discussion of results.

Discussion: The inadequate evidence limits the conclusions on our four objectives. (1) Drinking outcome, it seems that patient involvement in treatment planning does not have an effect. (2) Quality of life might be improved. (3) Enrollment might be increased. (4) Adherence was improved.

Conclusion: Very few studies have been performed in this field; hence, no clear recommendation can be given to clinical practice at this point.

PROSPERO Registration code: CRD42019124794

Introduction

It is well documented that the impact of excessive and dependent alcohol use is massive, both on the individual and on society (WHO Citation2014). Premature dropout and lack of success from treatment for alcohol use disorder is, however, not uncommon (Schwarz et al. Citation2018), and it has been difficult to identify a particular and single treatment approach that secures high level of treatment successes for all persons seeking treatment for alcohol use disorders (AUD). It has been suggested that the reason for this is that persons with AUD are heterogeneous in many aspects, and vary in terms of social background, gender, age, intelligence, mood, attitude to their alcohol use, social support, the severity of their drinking problem, and a wide range of other individual characteristics (Burnam and Watkins Citation2006). Such differences may have prognostic significance, as for instance patients whose lives function better have a later onset of AUD, and patients who have less family history of alcohol problems, are more likely to recover (e.g. Moss et al. Citation2010). However, other patient-specific differences may be as important as their characteristics. Patients may, for instance, differ in terms of their goals for treatment and in their perceived treatment needs; not only are patients who have suffered fewer consequences from their alcohol use, who have fewer non-drinking people in their social network, who are young or who come to treatment for the first time, less likely to have a goal of total abstinence than patients with the opposite characteristics (DeMartini et al. Citation2014), the patients also differ in relation to how they interpret their drinking behavior and what they expect from treatment (Nielsen Citation2003). The heterogeneity within the AUD patient population, and the difficulty in identifying a particularly successful treatment approach for the patient population as a whole, has long led researchers to conclude that ‘one size does not fit all’. Instead, the hypothesis was put forward that some treatments would be more attractive and effective in targeting specific patient groups than others, the so-called Matching Effect (Gibbon et al. Citation2010).

However, two large matching studies, Project MATCH and UKATT, conducted within the alcohol field, have been inconclusive. In Project MATCH, drinking and negative consequences declined regardless of which treatment the patients received (Babor Citation2008). Of the 16 predicted matches, only one was supported by the findings in Project MATCH: patients with low psychiatric severity turned out to fare better with the Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) compared to the other two treatments (Allen et al. Citation1997). In the United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) was compared to the Social Behavior and Network Therapy (SBNT), but as was found in Project MATCH, the patients improved similarly in both treatment groups. None of the matching hypotheses could be confirmed, and the UKATT even failed to confirm the few findings from Project MATCH (Heather et al. Citation2008). In other words: expert matching patient to treatment options does not seem to improve treatment outcome (Hesse et al. Citation2017; Project MATCH secondary a priori hypotheses Citation1997).

While letting clinicians match patients to treatment options did not provide the wanted results, there are, however, indications that patients matching themselves to treatment options might provide better outcome. For example, a randomized controlled study on allocating patients to either abstinent treatment goal or controlled drinking goal, not only found reduced drinking days, less heavy drinking and improved abstinence in the controlled drinking group, but also that 30 of 35 patients in the controlled drinking group agreed on the treatment goal, whereas only 12 of 35 in the abstinence group agreed on treatment goals (Sanchez-Craig Citation1980). Perhaps an important piece of the puzzle is having clinicians and patients collaborate in the treatment planning.

The Shared decision Making (SDM) concept was founded in 1982 and has gained increasing interest in addiction treatment throughout recent years (Elwyn et al. Citation2017). SDM is a collaborative approach to health care that is supposed to empower the patient and improve patient autonomy. In SDM, the health care provider shares information on treatment, risk, benefits, and consequences, and the patient shares information about his/her values, preferences and life circumstances (Edwards and Elwyn Citation2009). Ideally, it follows that they develop a treatment plan together. The decision-making process varies in length and number of sessions, but it need not be time-consuming. For example, a feasibility study of implementing shared decision making in general practice for people in need of health behavior change found, that it is feasible to use a novel paper-based decision aid. Both patients and staff appreciated the tool’s structure and the facilitation of the decision process (Cupples et al. Citation2018). Treatment planning in general practice might be very different from that in clinical practice, for instance due to relatively shorter consultations, but a model for SDM in clinical practice has been developed as well. The three-talk model of shared decision making is a model for SDM in clinical practice developed by Elwyn et al. (Citation2017). This model gives a general framework for SDM that can be altered in the specific context. The model is divided into three stages: team talk, option talk, and decision talk. The main point in the team talk stage, initially termed choice talk, is to establish collaboration and assure patients that they are not alone in the decision making. Option talk refers to the stage where patients are presented to the options available and informed about potential harms and benefits. The last stage in the model is decision talk where the patient’s preferences are elicited and integrated in the decision (Elwyn et al. Citation2017). In theory, SDM should reduce ambivalence and encourage patients to be open toward interventions, thus leading to improved adherence.

A systematic review of SDM in health care, in general, found that SDM concerning long-term decisions embedded in the overall treatment course, for instance healthy lifestyle changes, led to improved overall treatment outcome (Joosten et al. Citation2008). The positive findings include treatment of depression, schizophrenia, diabetes and asthma. Contradictory to these findings, a systematic review of patient preferences and SDM in treatment for addiction from 2016 found, that only 3 out of 25 studies showed a significant effect on treatment outcome (Friedrichs et al. Citation2016). However, the authors stated that generalization is doubtful because the included studies were heterogenous in size, treatment options, and type of addiction. Furthermore, the methodologies were ranging from surveys of patient preference to RCT of SDM. 14 of the 25 studies were performed in alcohol treatment field and only 4 of these studied SDM. These reviews, however, indicate that SDM in psychotherapy of addiction treatment may be different from that in mental health treatment, and that planning treatment for various kinds of addiction may differ. Or, it might simply mean, that there have not been enough trials of SDM in addiction treatment to make solid conclusions of SDM in this very heterogeneous group.

Focusing entirely on SDM as a method for deciding appropriate treatment might be a limitation and may not include the broader spectrum of allowing patient involvement in treatment planning. Instead, SDM should be considered on a continuum between, but not including, the paternalistic approach, where the clinician solely decides the treatment method, and informed choice, where the patient freely chooses the treatment option (Elwyn et al. Citation2012). If SDM is considered as such a continuum for patient involvement, different trials are, most likely, different in methodology resulting in different results.

According to Elwyn et al. (Citation2012) SDM should take place throughout treatment, whereas Informed Choice often is only used at the beginning of treatment. In the present review of the literature on alcohol treatment studies, we wish to include the continuum of SDM and Informed Choice, which in total will cover patient involvement in treatment planning.

The purpose of the study is to investigate whether patient involvement in treatment planning in treatment for alcohol use disorders improves adherence, enrollment and other treatment outcome.

Aim

Through a literature search, this review will seek to answer if outcome of alcohol addiction treatment is improved if patients participate in treatment planning. The focus will be on the following outcome measures: drinking outcomes, enrollment in treatment, attendance to the treatment course, and quality of life. These outcome measures are chosen because they are clinically meaningful; treatment success is usually measured by reduced drinking and/or improved quality of life (Frischknecht et al. Citation2013; Mann et al. Citation2017). Enrollment in treatment and following a treatment plan are also important measures, because knowledge on these measures can lead to optimization of resources.

Materials and method

Search strategy for identification of studies

The literature was searched in MEDLINE, PsychINFO and PubMed databases. Searches were done in full text and all databases were searched from their commencement date until January 2019. Reference lists of relevant studies were searched for additional studies. To ease readability, we have summarized the search below. The full search strategy can be obtained from the first author on request or at the journal’s Supplementary material for the present article.

Addiction or alcohol abuse or alcoholism or alcohol dependence, and shared decision making or informed choice or treatment planning or medical decision making or decision making or patient preference or patient participation, and abstinence or drinking days or quality of life or compliance or patient satisfaction or adherence.

Truncations, thesaurus terms, and MeSH terms were used. Keywords were clustered in three groups: patient characteristics, intervention and outcome measures.

PRISMA checklist was used to structure the review. PROSPERO registration code: CRD42019124794

Inclusion- and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Report on an original (empirical) research study.

Published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Study design focused on patients collaborating with staff in treatment planning or choosing treatment option.

Involving an intervention group and a control group.

Age 18 or older.

Including one or more of the following outcome measures: Alcohol consumption, quality of life, retention, or adherence.

Only articles in English, German, or Scandinavian languages were included.

Excluded studies were those in which alcohol measures were not explicitly separated from other addiction measures.

Methodological quality assessment

Guidelines from the Cochrane Back Review Group (Furlan et al. Citation2009) were used to assess the quality of the studies. This guideline also suggests that Quasi-RCT studies are included if the search results in fewer than 5 RCT studies, which is the case in the present review. In addition, section B of the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist was used to determine results. Two researchers independently assessed the quality. In case of disagreement, the studies were discussed to determine the quality. If agreement could not be reached, a third researcher, Bent Nielsen, was invited to assess the quality.

Results

Study selection

The search resulted in 717 references via PubMed, 308 via PsychINFO and 589 via MEDLINE. 5 articles were added to the search from references in articles. After deleting duplicates, the search resulted in 1203 different studies. Duplicates were removed using EndNote reference manager.

One reviewer screened all 1203 articles based on title and abstracts. After this screening, 13 articles remained and were carefully read by two reviewers. The articles not included were reviews, editorials, quality assessment reports, and letters ().

Excluded studies

A further 7 articles were excluded, since they were either descriptive studies of differences between patients’ and clinicians’ treatment preferences, surveys examining patients’ desire for autonomy, or investigating patients’ preferences without inviting patients to partake in treatment planning.

Study characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies (N = 6) are shown in . Three studies, Thornton et al. (Citation1977), Ojehagen and Berglund (Citation1986), and McKay et al. (Citation1995), were relatively old and conducted at the very beginning of the implementation of shared decision making in mental health. Two studies, Thornton et al. (Citation1977) and Joosten et al. (Citation2009), investigated the effect of patient involvement in choice of treatment goals. Three studies, McKay et al. (Citation1995), McCrady et al. (Citation2011) and McKay et al. (Citation2015) investigated patient involvement regarding the choice of treatment method. One study, (Ojehagen and Berglund Citation1986) investigated both.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

The methods of patient involvement in the included studies are heterogenous. Joosten et al. (Citation2009) investigate a collaborating approach being the strictest form of SDM. McKay et al. (Citation1995), McCrady et al. (Citation2011) and McKay et al. (Citation2015) make use of an informed choice approach. Thornton et al. (Citation1977) and Ojehagen and Berglund (Citation1986) measured if patients agreed to participate in an experimental treatment program or preferred TAU, apart from that, patients had no influence on treatment planning. Although there was no direct patient involvement in treatment planning in these studies, they do provide information about the treatment, and measure whether the treatment is preferable or not to the patient, which we consider to be equivalent to an informed choice approach. The studies are also heterogeneous in how often the patients are involved in the decision-making process, ranging from only at the beginning of treatment to several times throughout the course of treatment, the latter being the approach used in SDM in mental health (Elwyn et al. Citation2014).

The options that patients could choose from in the studies also differed in number as well as in content, see .

Methodological quality

Three studies (Joosten et al. Citation2009; McKay et al. Citation1995; McKay et al. Citation2015) met at least 6 out 12 quality criteria according to the Guidelines from the Cochrane Back Review Group, which is the cutoff for reaching ‘low risk of bias’. These three studies also reported treatment effects. Three studies (McCrady et al. Citation2011; Ojehagen and Berglund Citation1986; Thornton et al. Citation1977) met 5 or less of 12 risk of bias criteria and only (McCrady et al. Citation2011) reported treatment effect. We labeled these three studies ‘high risk of bias’.

The methodological quality of the included studies can be seen in .

Table 2. Methodological quality of included studies.

Effectiveness of patient involvement in treatment planning

Drinking outcome

Four of the included studies (Joosten et al. Citation2009; McKay et al. Citation1995; McKay et al. Citation2015; Thornton et al. Citation1977) investigated the impact of patient involvement in treatment planning on drinking outcomes. Of these four studies, two studies (Joosten et al. Citation2009; Thornton et al. Citation1977) measured patient involvement regarding treatment goal, and two (McKay et al. Citation1995; McKay et al. Citation2015) measured patient involvement regarding treatment method.

Thornton et al. (Citation1977) had six drinking outcome measures at 6-months follow-up: abstinent the entire 6 months during treatment, abstinent the last 30 days, not intoxicated in the last 30 days, drinking less post-treatment than before treatment, onset of relapse, and onset of intoxication. They found significant improvement in favor of patient involvement in treatment planning on all six outcome measures.

Joosten et al. (Citation2009) measured abstinence at the end of treatment and at 3-month follow-up. They found no difference on EuropASI Alcohol Severity Score between SDM and control group.

McKay et al. (Citation1995) had 2 drinking outcome measures: number of days of alcohol intoxication, and alcohol related problems the last 30 days. They found no difference.

McKay et al. (Citation2015) had 4 outcome measures: number of drinking days the last 30 days, number heavy drinking days the last 30 days, % of drinking days the last 30 days, and % of heavy drinking days the last 30 days. They found that the control group had both fewer drinking days and fewer heavy drinking days if patients had dropped out of treatment prior to week 2. There was no difference between groups if patients dropped out later than week 2, or completed the program.

McCrady et al. (Citation2011) and Ojehagen and Berglund (Citation1986) did not measure drinking outcome.

In sum, patient involvement in treatment planning did not improve drinking outcome. The only study identifying a difference was the one being the strictest in informed choice; the patients simply volunteered to participate in a predefined treatment regime. All three studies, showing no effect on drinking outcome, included patients with substance use disorder.

Enrollment as outcome measure

One study McCrady et al. (Citation2011) measured whether patient involvement in treatment planning influenced the number of patients enrolled in treatment.

McCrady et al. (Citation2011) measured enrollment based on the number of patients agreeing to participate. They found that patient involvement increased acceptance to start treatment, compared to standard procedure. There was no difference between individual and couple therapy on session attendance. (This was not compared to treatment as usual and is, therefore, not included in the adherence section below).

Adherence as outcome measure

Three studies (McKay et al. Citation1995; McKay et al. Citation2015; Ojehagen and Berglund Citation1986) investigated adherence as an outcome measure.

McKay et al. (Citation2015) measured adherence based on session attendance. They found that patient involvement had a significantly positive effect on the number of sessions attended.

McKay et al. (Citation1995) measured adherence based on completion rate, but found no difference.

Ojehagen and Berglund (Citation1986) did not report differences between groups.

In sum, there are indications that treatment adherence may be improved early in the treatment course, but adherence may fade out toward the end of treatment.

Quality of life as outcome measure

Joosten et al. (Citation2009) measured quality of life by the EuroQoL-5D. They found significant difference between the groups in favor of those randomized to SDM. The other studies did not measure quality of life.

Discussion

Our systematic search identified only six studies that investigated the impact of patient involvement in treatment planning in alcohol treatment. They were very heterogenous in methodology, design and outcome measures. Furthermore, 3 studies were rather old (1977, 1986, 1995) and two of these only met 5 or less of the 12 quality criteria, thus, only hesitant conclusions on our four objectives for the present study can be drawn:

It seems that patient involvement in treatment planning does not have any effect on drinking outcomes. Only one of the included studies found significant difference in favor of patient involvement in treatment planning, whereas another study found significant difference in favor of the control group, however, this difference was only present if patients dropped out of treatment prior to the second week of treatment. For those who completed treatment, there was no difference. The other two studies found no difference. In addition, the study that only included patients with alcohol use disorder found a difference in favor of patient involvement.

Patient involvement in treatment planning may lead to improved quality of life, but this was only measured in one study.

It may be that enrollment is increased when patients are offered a choice of treatment options rather than just one option.

Adherence to treatment may be improved by patient involvement in the treatment planning.

There may be several reasons why studies of patient involvement in treatment planning yield different results. A descriptive study of patients’ and clinicians’ perspective on treatment goal in addiction health care (Joosten et al. Citation2011) found differences between patients’ and clinicians’ perspective, but; these differences became more aligned during treatment. In the present review, we found indications that patient involvement in treatment planning might improve adherence, which could be a result of aligning treatment goals at the very beginning of treatment (Graves et al. Citation2017). In the context of Self-Determination Theory, Ryan and Deci (Citation2017) investigated the influence of choice in different cultural settings and identified evidence of enhanced experience of autonomy and relatedness, when individuals were given a choice, or if their preferred choice matched the option chosen by a trusted other. This could explain why patient involvement in treatment planning, has an impact on enrollment and adherence, since perceived autonomy and relatedness might, thus, be present when treatment starts. Self-Determination Theory, then, can provide a theoretical framework for understanding how and why patient involvement improves adherence and enrollment. Additionally, Graff et al. (Citation2009) identified various aspects influencing adherence and enrollment in alcohol addiction treatment. The study measured women’s outcome of treatment and found that elements such as individual treatment, fewer symptoms of alcohol dependence, satisfying marital relationship, spouses who drank, matched preference for treatment option, age, and age of onset of alcohol diagnosis influenced attendance of treatment sessions and engagement in assignments i.e. homework. This indicates, that many factors play a role in treatment planning and that the patient’s life circumstances should not be ignored.

The result of the present review did not provide evidence of patient involvement in treatment planning improves outcome of alcohol treatment, which seems peculiar if enrollment and adherence is improved. However, similar results were found by Adamson et al. (Citation2005) who measured patients’ preference for treatment options after being randomized to treatment method. They found no difference in treatment outcome regardless of whether patients received the treatment method they preferred, or not. The discouraging results on treatment outcome might be because the alignment of treatment perspectives during treatment is caused by external pressure, rather than by autonomy or integrated values, resulting in relinquished motivation, when treatment ends. If that is the case, SDM should be a continuous process in treatment, ensuring that changes in life circumstances, treatment goals, etc. are taking into consideration throughout the treatment. To our knowledge, SDM as a process throughout the complete treatment course, has only been investigated by Joosten et al. (Citation2009) and needs to be tested in more trials. Elwyn et al. (Citation2014) has argued that Motivational Interviewing (MI) can be merged into a model of SDM in mental health. MI reduces ambivalence and supports behavior change (Miller Citation1983) in a way that gives the patient an experience of autonomy leading to intrinsic motivation. In theory, MI can support SDM as a process, but specific tools for measuring MI in relation to SDM need to be developed. For the time being, measurement tools, developed by the Self-Determination Theory, could be used to measure motivation throughout treatment, which could provide indications on how SDM can be modified to fit alcohol addiction treatment and other treatments based on psychotherapy and require long-term behavior change.

An additional, but very hesitant, point from our systematic search is a potential difference in outcome, when patients have a co-occurring substance use disorder. Among the studies reporting drinking outcome measures, three of the identified studies included patients suffering from substance use disorder in addition to alcohol use disorders. This could affect the results, even though drinking outcome was measured separately. When conducting a cross-sectional study in Warsaw, Poland and Berlin, Germany of trauma patients’ desire for autonomy in medical decision making, Neuner et al. (Citation2007), for instance, showed that the illicit substance-using patient group had a reduced desire for autonomy. In the present review, the three studies that included patients with concurrent alcohol and substance use disorder, were the ones that found no effect on drinking outcome. Despite that alcohol use was measured separately, the other drug involvement might, thus, have influenced the results.

The preference for an opportunity to choose might be different for patients with substance use disorder, but according to one of the most commonly used theories of motivation, Self-determination Theory, giving people a choice will enhance autonomy. According to the theory, autonomy is one of three basic psychological needs, the others being relatedness and competence. These other two basic psychological needs are likely to be enhanced when people can relate to the caregiver or treatment regimen, and feel competent in reaching the goals. For example, if they cannot relate to the options available, or if the options are too many, the basic need for competence is thwarted. A very likely way to thwart the basic need of relatedness is if the collaboration between clinician and patient is ineffective. Therefore, inviting patients to participate in treatment planning regarding treatment method will, most likely, yield a better outcome, but also a more complicated planning, which needs to be measured throughout the treatment.

Further research is needed regarding the effect of patient involvement in treatment planning, when implemented in various stages of treatment. Furthermore, clarity is needed on whether there is a difference in treatment outcome if patients have a cooccurring substance use disorder or not. Last, measuring quality of life is important in future studies on patient involvement in treatment planning. Regarding the last two recommendations, an ongoing study, Hell et al. (Citation2018), is investigating the outcome of patients matching themselves to treatment options, which might provide useful information.

Limitations and strength

It is a limitation to the present review that the search was restricted to the English language search terms, and that only studies reported in English, German or Scandinavian languages were included. It is a limitation that we deviated from the PRISMA guidelines in the initial analysis of the studies by using only one investigator, where the guidelines recommend two blinded investigators. This could lead to some studies having been excluded by mistake. It is, on the other hand, a strength of the present review that the systematic search was performed in multiple databases, and that the databases were searched from the commencement date. Another limitation is that the framework of the treatment can interfere with the outcome, because TAU psychotherapy approaches can be closely related to the spirit of SDM, hence reducing the difference between intervention arm and TAU.

Conclusion

The most important finding of this review is that there are very few studies performed in alcohol addiction treatment. This calls for an urgent need for more research in this field, especially since alcohol addiction affects so many people’s life and has a profound impact on people’s health. This systematic review found that patient involvement in treatment planning might improve the enrollment of patients and adherence to alcohol addiction treatment. Furthermore, we found indications of an improvement in the quality of life, when patients participate in treatment planning; however, only one study measured this. No improvements were found on drinking outcomes, although it is possible that co-occurring illicit substance use may be a confounding factor. Three out of four studies, that found no effect on drinking outcomes, included patients with co-occurring substance use disorder.

The included studies were too heterogeneous in design and method to do a meta-analysis, resulting in a narrative synthesis of the results, leading to suggestions for further research rather than firm conclusions.

Author contributions

Morten Ellegaard Hell took the initiative to make the review and contributed to all sections of the manuscript. Anette Søgaard Nielsen contributed to all sections of the manuscript.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/124794_STRATEGY_20200117.pdf.

Search_strategy.docx

Download MS Word (15.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor William R. Miller, University of New Mexico, and professor Bent Nielsen, University of Southern Denmark, for comments on previous versions of the manuscript. Also, we wish to thank PostDoc Angelina Mellentin, University of Southern Denmark, for statistical advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamson S. J, Sellman D. J, Dore G. M. 2005. Therapy preference and treatment outcome in clients with mild to moderate alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 24(3):209–216.

- Allen J. P, Mattson M. E, Miller W. R, Tonigan J. S, Connors G. J, Rychtarik R. G, Townsend M. 1997. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 58(1):7–29.

- Babor T. F. 2008. Treatment for persons with substance use disorders: mediators, moderators, and the need for a new research approach. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 17(S1):S45–S49.

- Burnam M. A, Watkins K. E. 2006. Substance abuse with mental disorders: specialized public systems and integrated care. Health Aff. 25(3):648–658.

- Cupples M. E, Cole J. A, Hart N. D, Heron N, McKinley M. C, Tully M. A. 2018. Shared decision-making (SHARE-D) for healthy behaviour change: a feasibility study in general practice. BJGP Open. 2(2):bjgpopen18X101517

- DeMartini K. S, Devine E. G, DiClemente C. C, Martin D. J, Ray L. A, O’Malley S. S. 2014. Predictors of pretreatment commitment to abstinence: results from the COMBINE study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 75(3):438–446.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G. 2009. Shared decision-making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elwyn G, Dehlendorf C, Epstein R. M, Marrin K, White J, Frosch D. L. 2014. Shared decision making and motivational interviewing: achieving patient-centered care across the spectrum of health care problems. Ann Fam Med. 12(3):270–275.

- Elwyn G, Durand M A, Song J, Aarts J, Barr P J, Berger Z, Cochran N, Frosch D, Galasiński D, Gulbrandsen P. 2017. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 359:j4891

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S. 2012. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 27(10):1361–1367.

- Friedrichs A, Spies M, Härter M, Buchholz A. 2016. Patient preferences and shared decision making in the treatment of substance use disorders: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 11(1):e0145817.

- Frischknecht U, Sabo T, Mann K. 2013. Improved drinking behaviour improves quality of life: a follow-up in alcohol-dependent subjects 7 years after treatment. Alcohol Alcoholism. 48(5):579–584.

- Furlan A. D, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M. 2009. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 34(18):1929–1941.

- Gibbon S, Duggan C, Stoffers J, Huband N, Vollm B. A, Ferriter M, Lieb K. 2010. Psychological interventions for antisocial personality disorder. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 16(6):CD007668.

- Graff F. S, Morgan T. J, Epstein E. E, McCrady B. S, Cook S. M, Jensen N. K, Kelly S. 2009. Engagement and retention in outpatient alcoholism treatment for women. Am J Addict. 18(4):277–288.

- Graves T A, Tabri N, Thompson-Brenner H, Franko D L, Eddy K T, Bourion-Bedes S, Brown A, Constantino M J, Flückiger C, Forsberg S. 2017. A meta-analysis of the relation between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 50(4):323–340.

- Heather N, Copello A, Godfrey C, Heather N, Orford J, Raistrick D, Team U. R. 2008. UK Alcohol Treatment Trial: client-treatment matching effects. Addiction. 103(2):228–238.

- Hell M. E, Miller W. R, Nielsen B, Nielsen A. S. 2018. Is treatment outcome improved if patients match themselves to treatment options? Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 19(1):219.

- Hesse M, Thylstrup B, Nielsen A. S. 2017. Matching patients to treatments or matching interventions to needs. In: Torsten Kolind, Betsy Thom and Geoffrey Hunt, editors. Handbook of drug and alcohol studies – social science perspectives. London: SAGE Publications.

- Joosten E. A, de Jong C. A, de Weert-van Oene G. H, Sensky T, van der Staak C. P. 2009. Shared decision-making reduces drug use and psychiatric severity in substance-dependent patients. Psychother Psychosom. 78(4):245–253.

- Joosten E. A, De Weert-Van Oene G. H, Sensky T, Van Der Staak C. P, De Jong C. A. 2011. Treatment goals in addiction healthcare: the perspectives of patients and clinicians. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 57(3):263–276.

- Joosten E. A, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert G. H, Sensky T, van der Staak C. P, de Jong C. A. 2008. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 77(4):219–226.

- Mann K, Aubin H. J, Witkiewitz K. 2017. Reduced Drinking in Alcohol Dependence Treatment, What Is the Evidence?. Eur Addict Res. 23(5):219–230.

- McCrady B. S, Epstein E. E, Cook S, Jensen N. K, Ladd B. O. 2011. What do women want? Alcohol treatment choices, treatment entry and retention. Psychol Addict Behav. 25(3):521–529.

- McKay J R, Alterman A I, McLellan A. T, Snider E C, O’Brien C P. 1995. Effect of random versus nonrandom assignment in a comparison of inpatient and day hospital rehabilitation for male alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 63(1):70–78.

- McKay J R, Drapkin M L, Van Horn D H. A, Lynch K G, Oslin D W, DePhilippis D, Ivey M, Cacciola J S. 2015. Effect of patient choice in an adaptive sequential randomization trial of treatment for alcohol and cocaine dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 83(6):1021–1032.

- Miller W. R. 1983. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 11(2):147–172.

- Moss H. B, Chen C. M, Yi H. I. 2010. Prospective follow-up of empirically derived Alcohol Dependence subtypes in wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol And Related Conditions (NESARC): recovery status, alcohol use disorders and diagnostic criteria, alcohol consumption behavior, health status, and treatment seeking. Alcohol Clin Exper Res. 34(6):1078–1083.

- Neuner B, Dizner-Golab A, Gentilello LM, Habrat B, Mayzner-Zawadzka E, Górecki A, Weiss-Gerlach E, Neumann T, Schlattmann P, Perka C. 2007. Trauma patients’ desire for autonomy in medical decision making is impaired by smoking and hazardous alcohol consumption–a bi-national study. J Int Med Res. 35(5):609–614.

- Nielsen A. S. 2003. Alcohol problems and treatment: the patients’ perceptions. Eur Addict Res. 9(1):29–38.

- Ojehagen A, Berglund M. 1986. To keep the alcoholic in out-patient treatment. A differentiated approach through treatment contracts. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 73(1):68–75.

- Project MATCH secondary a priori hypotheses. 1997. Project MATCH secondary a priori hypotheses. Project MATCH Research Group. Addiction. 92(12):1671–1698.

- Ryan R. M, Deci E. L. 2017. Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Sanchez-Craig M. 1980. Random assignment to abstinence or controlled drinking in a cognitive-behavioral program: short-term effects on drinking behavior. Addict Behav. 5(1):35–39.

- Schwarz A. S, Nielsen B, Nielsen A. S. 2018. Changes in profile of patients seeking alcohol treatment and treatment outcomes following policy changes. J Public Health. 26(1):59–67.

- Thornton C. C, Gottheil E, Gellens H. K, Alterman A. I. 1977. Voluntary versus involuntary abstinence in the treatment of alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 38(9):1740–1748.

- WHO. 2014. Global status report on alcohol and health – 2014 ed. Geneva: World Health Organization.