Abstract

Background

Drug-death bereavement is an understudied topic. We explore what bereaved parents experience after losing their child to drug use. The aim of the paper is to provide knowledge about what drug-death bereaved parents go through and study the kinds of help and support they receive.

Method

Reflexive thematic analysis is used to analyze 14 semi-structured in-depth interviews with Norwegian parents.

Results

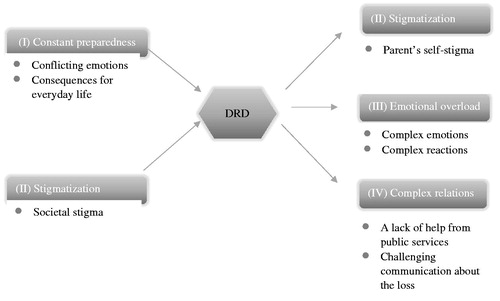

We generated four main themes: (I) ‘constant preparedness’ describes the burdensome overload that the parents experienced before death; (II) ‘stigmatization’ represents public and self-induced stigma; (III) ‘emotional overload’ refers to the parents’ complex and ambivalent emotions, such as anger, guilt and shock after the loss; and (IV) ‘complex relations’ describes the parents’ relations with public services and their personal social networks.

Discussion

We discuss how overload, before and after the loss experience, causes a special grief. How this overload, silence from helpers, self-stigma and complicated interactions with social networks contribute to the grief of these parents is also discussed. Potential implications for policy and practice are subsequently outlined.

Introduction

Bereavement after unnatural deaths (e.g. murder, suicide, early child death) is associated with serious mental and physical health difficulties (Dyregrov et al. Citation2003; Li et al. Citation2005; Stroebe et al. Citation2017), low levels of health-related quality of life (Song et al. Citation2010) and even an increased risk of early death for the bereaved parent (Li et al. Citation2003). Bereaved parents after unnatural deaths who struggle with grief-related emotions and reactions can potentially benefit from individualized help provided by public services and support from their social network, helping them to avoid major health problems (Stevenson et al. Citation2017; Dias et al. Citation2019). In order to offer the right kind of help, we need knowledge of the grief they experience.

Losing a child due to a drug-related death (DRD) is unnatural. Definitions of DRD vary, and there is a need for the clarification of terms regarding DRDs (Robertson et al. Citation2019). In the absence of any consensus about the term, we define DRDs as deaths caused by the intake of substances classed as narcotics and deaths among people who use narcotics where the cause of death is violence, accidents, infectious disease or other health disorders, which in different ways may be linked to drug use. DRD has reached epidemic proportions in the US; the age-adjusted rate of overdose deaths increased significantly by 9.6% from 2016 (19.8 per 100,000) to 2017 (21.7 per 100,000) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2019). In Europe, the mortality rate due to overdoses in 2017 was estimated at 22.6 deaths per million population (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction Citation2019, p. 80). Norway, where this study took place, has one of the highest reported prevalence rates of overdose in Europe (Norwegian Directorate of Health Citation2019, p. 5). As other research on bereaved persons following sudden and unexpected, self-inflicted or violent deaths has demonstrated that unnatural deaths are related to an increased prevalence of complicated grief among this population (Dyregrov et al. Citation2003; Heeke et al. Citation2017), there is need for particular attention to the situation of bereaved left behind after DRDs. Prolonged grief disorder (PGD) is by far the most common form of complicated grief. PGD is characterized by persistent separation distress and combined with cognitive, emotional and behavioral symptoms, resulting in functional impairment for at least six months following death (WHO Citation2020).

Turning to scientific investigations of relevance to DRD bereavement: Oreo and Ozgul (Citation2007) reported parental grief even before the child died from DRD. Parents described reactions such as cognitive intrusions, avoidance behavior and emotional distress due to the child’s drug use. Orford et al. (Citation2010) outlined how family life with a person who is using drugs can be highly stressful, with constant conflicts. Coping alongside a person who uses narcotics can be an oscillation between sacrificing one’s own interest versus withdrawing from him or her. It can entail being fearful to act versus feeling the need to contact services to deal with urgent concerns about their child (Maltman et al. Citation2019).

How family members experience drug-death bereavement has hardly been investigated. A systematic review by Titlestad et al. (Citation2019) identified only seven qualitative studies from Norway, Denmark, Brazil, the US, England and Scotland (da Silva et al. Citation2007; Grace Citation2012; Biong et al. Citation2015; Nowak Citation2015; Biong and Thylstrup Citation2016; Templeton et al. Citation2017; Feigelman et al. Citation2020) and one quantitative study from the US (Feigelman et al. Citation2011) which satisfied the inclusion criteria and were of good methodological quality. This systematic review suggested that family members who were aware of the drug use experienced years of uncertainty, despair, stigma, hopelessness and powerlessness before the loss. The results indicate that those bereaved as a result of a DRD perceived a heavier emotional burden and lacked even more support from their social environment than those bereaved by other types of unnatural and natural deaths.

A distinction is frequently made between drug- and alcohol-related deaths; research has covered both of these, either jointly or singly. Valentine and colleagues conducted the largest in-depth study covering both of these so-called substance misuse death, interviewing 106 bereaved by drug- and alcohol-related deaths, in England and Scotland. Drug- and alcohol-related death are likely to have different consequences for the bereaved (Valentine and Bauld Citation2018, p. 2, 7). Using drugs is an illegal activity and the addiction stigma is likely to be worsened by criminalization, since drug use is conflated with felonious conduct (Corrigan et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, people who die from an overdose are more likely to be male and young and to suffer a death that occurs early in the course of addiction (Templeton et al. Citation2017).

Most of the literature from the UK does not distinguish between the two different types of deaths described above. However, an article by Templeton et al. (Citation2017) did report specifically on their drug-death bereaved sample (n = 32). Templeton et al. (Citation2017) argue that their findings support Guy and Holloway (Citation2007) descriptions of drug death as a ‘special death’, highlighting the difficult circumstances surrounding the death, the stigma associated with DRDs, interactions with public services and an unworthiness about grieving. Special deaths are deaths characterized by a high level of trauma and can be socially stigmatizing or existentially problematic, with the attendant grief being frequently disenfranchized (Doka Citation2002). Templeton et al. (Citation2017) also reported that many of those bereaved after a DRD described living with a feeling of loss and grief, including before the loss, so-called ‘anticipatory grief’ (Rando Citation1986, p. 24), and that the bereaved struggled in accessing support from both formal and informal circles.

Valentine et al. (Citation2016) described substance misuse deaths as ‘stigmatized’ deaths. For the bereaved, they were said to be associated with disenfranchized grief. ‘Disenfranchized grief’ follows a loss that is not, or cannot be, openly acknowledged, depriving the bereaved of the opportunity to share their experiences with others and therefore the opportunity to receive social support (Doka Citation1999). It has long been understood that stigma exists in the relationship between an attribute with a person/group and some audiences who view that attribute as abnormal, as described in Goffman (Citation1963, p. 3). Goffman (Citation1963) stated that stigma is ‘in the eyes of the beholder’ and can be perceived from several perspectives. From a social psychological perspective, stigma has two dimensions (Corrigan et al. Citation2009). One is public stigma, i.e. negative attitudes of the general public toward individuals who possess an undesirable characteristic, such as substance abuse (Corrigan et al. Citation2011), and the other is self‐stigma, i.e. the internalization of public stigma and a consequential reduction in self‐efficacy and self‐esteem (Corrigan and Watson Citation2006). Stigma toward people who use drugs is well known (Corrigan et al. Citation2009). Goffman (Citation1963) wrote about ‘spill over’, where an individual’s ‘stains’ spill over to the next of kin in such a way that the social discredit affects them to the same degree. In this way, family members themselves become stigmatized through association with a relative who uses drugs (Corrigan et al. Citation2017).

In sum, while scientific investigation has recently increased understanding of grief following DRDs, there is much still to learn about this special type of grief, particularly to inform health care professionals and affected families. To fill the knowledge gap regarding bereavement following DRD, a large Norwegian study called ‘The Drug-death Related Bereavement and Recovery Study’ (in Norwegian, ‘The END-project’) was launched in the spring of 2017 at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. The purpose of the main project was to contribute to a greater understanding of the consequences of DRD for the deceased next of kin, their situation and needs, as well as enhancing quality and competence in health and welfare services. The main study is a mixed-method study, collecting quantitative data through a survey and qualitative data through interviews (ResearchGate Citation2019).

Since there have scarcely been any empirical investigation into bereaved parents’ grief following a DRD or about what help and support they need (Titlestad et al. Citation2019), the aim of this sub-study is to explore how parents’ experience drug-death bereavement and what different kinds of help and support do they receive.

Methods

This sub-study is an explorative, inductive study. To generate a phenomenological, hermeneutic understanding of how parents experience DRD, we used reflexive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). We searched specifically for a variety of grief experiences which can characterize drug-death bereavement. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were carried out, and NVivo 12, qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018), was used in the data analysis process. This paper was guided by ‘Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations’ (O’Brien et al. Citation2014).

Recruitment and sample size

In the period from March 2018 until the end of December 2018, drug-death bereaved family members and friends were enrolled on the main project. They were invited to fill in a questionnaire, either on paper or digitally. A flyer that described the project, and invited participants to take part in a survey, was sent to all Norwegian municipalities’ public email addresses. We also contacted personnel who were engaged in the Norwegian Directorate of Health project to reduce drug overdoses, involving 28 municipalities at that time. Recruitment was also facilitated through non-governmental organizations working with drug use, treatment centers, the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration (NAV) and crisis teams (either by mail or by handing out flyers). We disseminated information about the project through participation at conferences and various media such as television, radio and social media (Facebook and Twitter). ‘Snowball recruitment’ by participants and by collaborators in other research networks or professionals in clinical practice was another important recruitment strategy employed.

The interview sample in this sub-study was drawn from a total sample of parents (n = 95) who participated in the survey. There were 75 parents’ who agreed to be interviewed and were eligible for interview. The participants spoke fluent Norwegian and had lost a child to DRD at least three months prior to recruitment. No other restrictions were set for the time since death. A matrix describing the eligible parents’ characteristics was developed. The sample to be analyzed in this paper was selected according to pre-defined selection criteria; (1) gender, (2) parents’ place of residence (city or village, northern/central/western/southern/eastern geographical parts of Norway), (3) gender of the deceased, (4) time since loss, (5) participants’ age, and (6) age of the deceased.

Malterud et al. (Citation2016) have proposed a set of dimensions that to help determine sample size. These include the study’s aim, sample specificity, theoretical background, dialog quality and strategy for analysis. We adhered to Malterud et al. (Citation2016) for their guidance on ‘information power’ to ensure adequate size of the final sample. During the recruitment process, one mother withdrew for personal reasons and one of the recruited participants failed to attend the planned interview. We were unable to reach out to the latter individual, either during or after the interview time, and no explanation was given as to why the potential participant decided not to keep the pre-planned appointment. Sample size was constantly evaluated with regard to information power and after interviewing seven fathers and six mothers, we decided to equalize the sample according to gender, in case the descriptions specific to gender became relevant to our discussion. Another mother was therefore invited to participate. After interviewing her, and given that the contribution of new knowledge was limited, we concluded that we had reached a satisfactory level of information power.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews

A semi-structured interview guide, built on the questions in the survey that we wanted to explore in detail, was developed for the interviews. The guide consisted of five themes: (1) the time before the death, (2) the loss, (3) stigma from the environment and self-stigma, (4) help, support and coping, and (5) post-traumatic growth. In the preparation phase, the interviewing authors discussed codes that could possibly be relevant as follow-up questions in the interviews. During the interviews, we encouraged the participants to tell us about the deceased, their relationship to the deceased, the deceased’s living habits, the circumstances surrounding the death, their grief reactions and how the death affected their health, working situation and leisure time. In relation to stigma, we talked about attitudes emanating from their surroundings and how they and others in their network communicated about the loss. We encouraged the parents to reflect on support from family, friends, colleagues, social networks and support groups and help from health and social services, the police, ambulance personnel, priests, crisis teams etc. We also asked the participants to share their thoughts about potential barriers to support and what help and support they needed, in addition to barriers or facilitators of own coping and meaning making. However, first and foremost, the interview method followed the principle of ‘following the interviewee’, as the interviewer pursued the thoughts and reflections of the parents during the interviews, implying that the main themes in the guide were covered, but not necessarily in set order. Also, the interviewers welcomed new topics relevant to the research questions.

The interviews were carried out in the period August to December 2018. To synchronize the interview method and pilot-test the interview guide, the last author conducted a trial interview with a bereaved parent, with the first and second authors (interviewers) present. The interview was discussed with the bereaved and the research interviewers. The interview guide was adjusted according to discussions after the trial interview and prior to other in-depth interviews.

Following completion of the informed consent process, the first, second and last author conducted interviews in a private setting selected by the participant (home = 9, work office = 4, a hotel (sheltered space = 1). The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. In addition, all interviewers noted their general impressions immediately after each interview. The length of the interviews ranged from 1 h and 20 min to 3 h and 10 min, including required or desired breaks. Altogether, the transcripts consisted of 431 single-spaced pages (range 20–39).

Sample

The sample consisted of 14 parents: seven women and seven men, who were parents to 14 deceased persons in total. One parent represented two deceased people and a divorced couple represented one deceased person. All the parents were aware of the drug use and none of the deceased had died after first-time use. Ten of the parents had lost a son and four parents had lost a daughter. The time since death ranged from three to 126 months (mean = 38) and all parents reported (on a five-point Likert scale) to have been close to the deceased (12 reported to have been very close). Nine of the deceased died of a not-intentional overdose, one of an intentional overdose (suicide), two of illness, accident or violence, and two of unclear causes. The age of the deceased varied between 19 and 45 years (mean = 27.36) and the age of the parents ranged between 45 and 75 years (mean = 58.29). The participants came from all parts of Norway (north n = 2, central n = 2, west n = 5, south n = 2 and east n = 3), with eight living in a village and six in a town. Twelve of the parents were married/cohabitants, while one had a boyfriend and one was divorced. Only two of the 14 participants were still married to the other parent of the deceased. The parents were well educated (79% had received higher education beyond 12 years). Annual household gross income was in the range from 25,000 to over 125,000 euros and 42.9% had an annual household gross income of 75,000–99,999 euros. The income level in Norway is high, and the participants’ income was high compared to the average annual household gross income.

Reflexive thematic analysis of interviews

Braun and Clarke (Citation2019) describe a six-phase process for reflexive thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with the data; (2) coding; (3) generating initial themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) writing up. The phases are sequential; each builds on the previous one, and the analysis is therefore a recursive process. We analyzed the interviews as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019), conducting a reflexive thematic analysis with movement back and forth between different phases.

In order to become immersed and intimately familiar with their content, the first author (a social educator and PhD student) read and reread all the interviews, and as codes were developed, they were generated in NVivo. This was a back and forth process, suggesting codes, re-reading the interviews, changing/adjusting codes after discussions with the last author (a sociologist and senior researcher). The first and last authors examined the codes and collated data to identify significantly broader patterns of meaning (potential themes), then altered the codes in accordance with consensus discussions with the coauthors (two psychologists). Themes, defined as patterns of shared meaning, underpinned a central concept or idea (Braun and Clarke Citation2019). The clustering of themes was generated by moving back and forth between the phases. Led by the first author, all authors worked out the scope and focus of each theme, deciding on an informative name. A table of the codes and themes was then produced.

Trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced by thorough discussions among the coauthors. All authors agreed upon the coding framework, the interpretation of the data and the confirmation of descriptive and analytical themes. Researchers’ background and position affects what we choose to investigate, how we investigate, which findings we consider most relevant, and how we conclude (Malterud Citation2001; Palaganas et al. Citation2017). We aimed for an inductive approach, although we discussed that we - as researchers - needed to be aware of our contributions to the construction of meanings and of lived experiences throughout the research process.

Ethical considerations

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (The World Medical Association, 9 July Citation2018). This study was approved in February 2018 by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (reference number 2017/2486/REK vest).

All participants were informed, in writing when consenting to participate, and it was repeated verbally at the onset of the interview, what the purpose, method and procedure of the study was. It was further explained that the data would be published in a non-identifiable manner. The parents signed a written consent form and were assured of anonymity, confidentiality and the option to withdraw from the study at any time. The interview data were treated confidentially. All identifying information concerning transcripts and recordings was de-identified and stored on the research server at the university.

Care was provided to the participants during the entire interview process according to Dyregrov (Citation2004) recommendations concerning research on vulnerable populations. The participants were made aware of the possibility to contact the project manager if answering questions about difficult life experiences prompted a need to talk to someone afterwards. All the participants reported positive experiences relating to their participation, and many expressed gratitude for the opportunity to share their stories during the interviews, although they acknowledged feeling tired afterwards.

Results

Four main themes were generated from the analyses: (I) constant preparedness; (II) stigmatization; (III) emotional overload; and (IV) complex relations (). Each main theme contains several codes reflecting the content of numerous meaning units from all parents. Descriptions of drug-death bereavement include experiences from the time before the loss, such as dealing with a child with a severe drug problem and society’s attitudes toward people who use drugs, and how these experiences influenced the parents’ grief. After the loss, the parents described their grief on two levels: the intrapersonal level and the interpersonal level. The intrapersonal level deals with the bereaved (e.g. (III) emotional overload), while the interpersonal level relates to the bereaved and their surroundings (e.g. (IV) complex relations). Meanwhile, (II) stigmatization connects with both levels (self-stigmatization and stigmatization by others).

(I) Constant preparedness

The parents reported that their child’s use of narcotics had an enormous impact on their everyday life. This theme represents the time before the loss, when the parents prepared for the worst-case scenario. They were in constant readiness, prepared to step in if their child needed help, while putting their own life on hold. This period was described via the two codes: (a) conflicting emotions; and (b) consequences for everyday life.

Conflicting emotions

All the parents knew about the drug use prior to the death. They talked about how, over the years, they had feared they would lose their child. This fear was exacerbated by the child’s way of life. Several of the deceased individuals had taken multiple overdoses prior to the lethal overdose. In addition, some of the children had revealed that they had given up on life. They communicated distress over the fact that life had not turned out the way they had hoped, and that they had ceased trying to quit using narcotics. Although the fear had increased over time, many parents were still shocked and overwhelmed at the time of death.

Many also felt rejected. As their child’s drug use escalated, the parents said they felt helpless. Health and social workers’ obligations concerning professional secrecy kept them in the dark, and it was hard being kept out of the loop, not getting the information they needed to help their son or daughter. Neither knowing what to do, nor being in a position to help caused a high level of emotional stress. They described the situation, on the one hand, as hopeless; on the other hand, all of them had hoped for recovery at one time. To have a child with severe drug use problems was described as a roller coaster of complex emotions, which on many occasions was difficult to deal with. A father described the variety of emotions, oscillating between exhaustion and optimism:

It is extremely difficult to live so close, [the deceased] becomes a very demanding person. These extreme situations, where we had to call the police, are very demanding, it is shocking. And, especially, it is very demanding to constantly have a person who is sick, right? It rarely goes well. Then things went well for a period of time, I was optimistic, and then it went downhill, right, it was like a roller coaster. (ID 42)

The heights represented feelings like hope but, as is typical for a roller coaster ride, the drops got steeper and steeper for many, especially for the parents who lost a young adult. These parents witnessed how their adolescent offspring’s drug use escalated rapidly over a short period, feeling that their child was slipping through their fingers, unable to stop the motion.

Parents who for decades had dealt with their child’s drug use expressed an additional emotional conflict. Like other parents, they had hoped for a drug-free life for their child, especially after drug-free periods; but, at the same time, they experienced grief reactions. One mother described 20 years of anticipatory grief, as she had been in constant preparedness for her child to die (ID 160).

Consequences for everyday life

The child’s way of life had major consequences for the parents’ everyday life. While other parents experienced their child becoming independent, these parents reported that their child’s need for support escalated. They also reported that they felt rejected by the Child Welfare Services and the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration (NAV) and described confidentiality as a major barrier to cooperating with the services, especially during the child’s transition period from adolescence to adulthood. One mother described her hopeless position in terms of someone who has responsibility, but without the permission to take action:

I had called the Child Welfare Services, I had called the general practitioner, and the grandfather had called the mental health team, which did not have time available. There wasn’t much more we could do. I called the Child Welfare Services, and they said the only thing I could do is to admit her, but I didn’t have the authority to admit her anywhere. As I said, you don’t feel that you are getting help. And, all this time, there’s no one. It’s an eternal struggle. (ID 62)

(II) Stigmatization

This theme reflects parents’ reports about experiences of stigma: (a) societal stigma; and (b) parents’ self-stigma. The parents described how the stigmatization of people who use drugs was reflected in societal attitudes, that is, people presuming that being addicted to drugs is self-inflicted. They did not report that they perceived stigmatization by virtue of being parents bereaved due to a DRD, although they often struggled with self-inflicted stigma.

Societal stigma

According to the parents, society’s attitudes to drug use are reflected in stigmatizing statements, especially in online discussion forums where it is stated that people who have a drug addiction chose this life and need to get a grip on themselves. Many referred to comments that described people who use drugs as an outcast group in society. Such comments were perceived as prejudicial statements, and some pointed out that these comments are not in line with up-to-date best practices, which treat addiction as an illness.

Some of the parents also experienced stigma from professionals working within health and welfare services. In meetings with NAV, they found that their child was not taken seriously and sometimes not even spoken to. This mother ponders whether lack of communication is due to negative attitudes toward the person who uses drugs and lack of skills about addiction:

He [the deceased] said then, “Mom, they treat me differently when you’re with me”. I could give them the extra information, most likely […] They [people who use narcotics] are not treated very well in many places […] the attitudes the health professional has to the person who uses drugs. Honestly, I think they know too little about addiction problems […]One has to be very skilled to be able to handle addiction, and if you were to do it, it’s a long learning process (easy laughter) and you can’t give a three months’ stay and say “out, now you’re done”. (ID 7)

Professionals’ lack of consideration of their child’s wishes and needs mirrored helpers’ attitudes, the parents said. Some parents also described that they felt shamed by helpers in situations where the parent – in desperation – had contacted public services for emergency help.

Parents’ self-stigma

Shame and guilt for failing as a parent characterized the self-inflicted stigma which they reported to have imposed on themselves. In the process of self-examination, several of the parents felt that they had failed because they had not been able to protect their child or prevent their death. A father described his feeling of failure in this way:

As a parent, you have a role, one that we couldn’t really live up to, as we failed to play our role. You are supposed to protect [your child], make your child independent and get them to leave the nest, right? And, somehow, it does not work out. You haven’t finished the task, and it’s kind of shameful, yes, you’ve failed a bit in living up to the society’s expectations? Maybe in relation to your own social standing. I know it’s not like that, but the feeling associated with this, that’s what the feeling says to me, well, that’s what makes it a little difficult. (ID 39)

Parents stated that they were aware that the stigma they had imposed on themselves did not necessarily reflect other peoples’ thoughts or attitudes. A mother explained that she felt like she did not live up to society’s standards about how to be a responsible parent and therefore she over interpreted others’ behavior:

Well, I know everyone thinks it […] if you have a child who uses drugs, then, in a way, you haven’t been good enough. So, you’re looking for it, the blame in other people’s eyes, you see it, even if it’s not there. (ID 125)

Although they ruminated about whether people looked down on them, many of the same parents pointed out that there was an absence of stigma from their social support network. They were comforted by people in their social network, who reassured them about being good parents and stated that this could have happened to anyone. However, it was very difficult for them to absorb such opinions, as views of people in their network were overridden by their own inner self-inflicted stigma.

(III) Emotional overload

The parents reported that their search for answers to their child’s troubles and death affected their emotional life and behavior. After the loss, they experienced an overload of complex and ambivalent emotions as well as complex reactions due to the loss of their loved one. This overload was connected to two codes: (a) complex emotions; and (b) complex reactions.

Complex emotions

All 14 parents expressed a breadth of emotions triggered by the loss. The most striking feelings were anger, guilt, relief and shame. Especially during the first years after the loss, many parents described a rapid oscillation between various feelings mixed with rumination. The emotion that was most often expressed was anger, especially anger toward different health and welfare services:

So angry […] I’m angry at her [the deceased], I’m angry at the healthcare services. I’m looking for someone to blame, so if I can’t blame myself, then I must be able to blame someone else and then it must have been someone else’s fault […] probably the healthcare services or child welfare or the police. (ID 62)

Guilt and shame were commonly described, for failing as a parent and particularly guilt for not being able to stop their child from using drugs. They found that shame caused by society’s ideals or expectations was easier to put aside than feelings of guilt. Some of them expressed relief on behalf of the deceased, relief for others or relief on their own behalf. Parents who expressed relief had either lost a child after decades of drug use, or the load prior to the death from their perspective was so heavy that no other solution than a tragic outcome was to be expected. All the parents described their child’s resources and dwelt on the life that the child had never had.

Complex reactions

Even though the parents feared for their child’s life, their death was described as a shock and they reacted both mentally and physically to the loss. The consequences were social isolation and an increased concern for and a fear of losing others. Those who apparently struggled the most were parents who either had lost their only child or their child had been an enduring strain on them. These parents also lost an important part of their identity: the role as a full-time helper and/or as a parent. Like this father, a few parents struggled to find purpose in life:

You become a parent, and the world changes. And then you lose your child, then the world changes again, it’s not the opposite of becoming a parent, maybe much bigger on many levels […] Everything is about the child […] So when all that disappeared, then all our tasks disappeared, so, we are in such a very big vacuum in terms of figuring out what, what now, what should we do next, what should we do, why, what is the point really? (ID 39)

Thinking of the deceased, and what they could have done differently, kept some of the parents awake at night. Other reactions, such as sleeping problems, and physical reactions, such as feeling tired, nauseous, dizzy, exhausted and anxious, were also described.

(IV) Complex relations

Overall, the bereaved stated that relations with public services and their personal social networks were complex. As was the case during the time before death, most experienced a lack of help from public services. In general, they considered the support from family and friends to be good, although communication about the loss was difficult for both parties involved. Such complex relations were described in terms of two codes: (a) a lack of help from public services; and (b) challenging communication about the loss.

Lack of help from public services

All of the parents described that they did not get the help they needed from public service, though the meetings with first responders (i.e. police, doctors, paramedics, priests and undertakers) were described as professional. Most bereaved experienced that they got information about what had happened, and that priests and undertakers facilitated a dignified memorial service for the deceased. When the funeral was over, however, only a few representatives from the public services reached out to the bereaved. Those who received help had to ask for this themselves and only one of the parents was offered help from a local crisis team.

The first to arrive were the doctors and the ambulance staff, and then came the police and morticians, and somebody told me that, if I needed to talk to someone, I could call someone [laughter]. I received the number for a crisis relief team, I tried to call once, around Christmas, but they closed at 8 p.m., so there wasn’t much help in that. (ID 123)

Those who asked for help sought help primarily from a general practitioner. Sickness benefits from the National Insurance Scheme, graded from 100% down to 20%, were used as a return-to-work strategy. A few parents also reached out to their child’s case manager and asked them for a follow-up appointment so they could go through what had happened in the days up to the death. Although this help was appreciated, the bereaved had an unmet need to talk to professionals, especially concerning how to cope with their ruminations about ‘what went wrong’.

Challenging communication about the loss

Most of the parents found that their social network, such as family members, colleagues, friends and friends of the deceased, provided the support they needed. Despite being in shock, and not being able to respond to the care from their surroundings, they stated that people in their networks whom they were close to never gave up on them, although they differed in their views concerning how the loss had affected their way of communicating with others. Some said that losing their child had made it easier to talk to others and to share feelings and experiences. Others said that they had pulled back and only shared thoughts with a few close family members. Some were afraid that their grief was an unbearable burden to place on others, while others found that people were insecure and did not know what to say, which this mother and other bereaved interpreted as an indication of not wanting to hurt the bereaved parent:

I think others do not know what to say and how I will react. Some people find it very difficult if others gets very emotional, starts crying for example, others find it very difficult to handle that […] I have siblings who are health professionals, I thought that maybe they would try, but it seems difficult even for them. There is no unwillingness, they don’t know how to reach out. (ID 15)

Discussion

The themes identified from the data, (I) constant preparedness, (II) stigmatization, (III) emotional overload and (IV) complex relations, support the suggestion that DRD is a special kind of death. In line with Doka’s (Citation2002) definition of a special death, the parents in this study experienced stigma both before and after their child’s death. Before the death, there seemed to be a spillover effect from the stigmatized drug user (especially in meetings with helpers), while, after the death, the parents experienced an intrusive kind of self-stigmatization. This self-stigma was triggered by shame and guilt about failing as a parent and not fulfilling society’s norms about successful parenting. There seem to be high levels of stress inherent in the parents’ descriptions of constant preparedness and oscillating between conflicting emotions. We maintain that the emotional overload before and after death, combined with the self-inflicted stigma that the parents experience, imposes a considerable burden resulting in both a special death and a special grief.

The special grief of drug-death bereaved parents

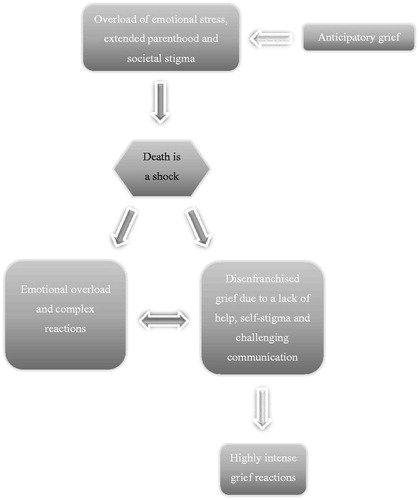

This study supports previous findings about parents experiences of emotional overload before death and their constant fight to find help for the child (Oreo and Ozgul Citation2007; Orford et al. Citation2010; Maltman et al. Citation2019). The descriptions of a constant preparedness showed how difficult it can be to live with a child using narcotics. Rejection from the Child Welfare Services and NAV, as well as a lack of cooperation due to confidentiality, had major consequences for the parents’ everyday life. The children were all over 18 years and therefore considered ‘adult’ in Norway where this study took place. However, to put this in perspective, the transition from childhood to adulthood in industrialized societies takes longer than it used to (Arnett Citation2000). Many young people still need emotional, economic and practical support after receiving the age of majority. The term ‘extended parenthood’ reflects the consequences that this extension has for parents who have children who need this continued support (Tysnes and Kiik Citation2019). Although the person who used drugs was considered an independent adult at the time before their death, the lack of tailored help from health and welfare services led to the parents in our study experiencing a need for extended parental involvement. The parents took over responsibilities which normally – at this time in the child’s life – should have been handled by their child him- or herself. They had continued to provide the child with all types of support, while, at the same time, dealing with their own emotional ‘roller coaster’. These findings illustrate that drug-death bereavement is complex and that an overload before death affects the parents’ grief after death (). These results also speak to the need to enhance cooperation between the person who uses drugs, their next of kin and public services.

Even though all of the parents were aware of their child’s drug use and feared losing their child, many nevertheless experienced their child’s death as a shock. As reported by da Silva et al. (Citation2007), a chaos of conflicting emotions and reactions, such as grief, anger, guilt, self-blame and relief, followed the unexpected death. The bereaved who had years of experiences with their child’s drug use and who described anticipatory grief reported the same spectrum of complex grief emotions or reactions as those bereaved with less preparation and/or forewarning.

The parents in our study were essentially angry with public services. Excessive bitterness or anger related to the death are typical reactions to bereavement (Stroebe et al. Citation2007). In the Brazilian study by da Silva et al. (Citation2007) secrecy regarding drug use followed by DRD aroused strong feelings of anger, while Templeton et al. (Citation2017) reported that anger was directed toward those they believed were involved in or responsible for their loved one’s death. By contrast, characteristics of the Nordic welfare states are a high degree of equality in services, a high level of taxes and a high level of public spending on welfare (Greve Citation2007). We believe there is a difference between the Brazilian/UK and the Norwegian studies, that the Norwegian parents’ anger is for not giving them public services they expected to get from the welfare state. Our results also show that, after their child’s death, the parents ruminated about why the child had not received this help, as well as why they themselves were not offered help to cope with the loss. Based on this study’s findings and other studies about drug-death bereaved in different countries of the world, it can thus be suggested that anger and frustration, reflected in rumination, is a central feature of the special kind of grief following a DRD.

We have reasoned that disenfranchized grief was described in our findings, although in different forms than in previous studies of drug-death bereavement. Livingston (Citation2017, p. 231) and Valentine et al. (Citation2016) described losses that were unacknowledged and/or forbidden, while, in our study, the parents described their losses as acknowledged (i.e. by their social networks). Still, there are different types of disenfranchized grief (Thompson and Doka Citation2017, p. 178). Disenfranchized grief can also be self-imposed, in which the bereaved take on the social and cultural norms and attitudes of those around them in relation to what deserves to be grieved over (Doka Citation1999). Although it is unclear how self-stigma determined whether or not the parents in fact grieved in public, several of the bereaved described the stigma that they had imposed on themselves, since they felt shame and guilt about failing as a parent. In addition, a lack of public services could have contributed to a feeling of unacknowledged grief. A national guideline Psychosocial Interventions in the Event of Crisis, Accidents and Disasters recommends municipalities to activate psychosocial crisis teams for the bereaved after a sudden and potentially traumatic death (Norwegian Directorate of Health Citation2016, p. 31–35). Despite this recommendation, when their child died, only one of the 14 parents received help from public services without asking for it. The finding that the drug-death bereaved are less likely to access public services after such a traumatic, unnatural death is in line with the findings of other studies (Biong et al. Citation2015; Valentine et al. Citation2016).

We believe that stigmatization on a group level during the time before the child died, as well as the demonstrated self-inflicted stigma that the parents placed on themselves, is a typical feature of drug-death bereavement. Shame and guilt about failing as parents characterize one of the extra burdens that the parents had imposed on themselves and, according to Jie Li et al. (Citation2019), guilt might be a core symptom of grief complications and depression. Complicated grief has been reported as being high in studies of other bereaved samples after a DRD (Templeton et al. Citation2016). As illustrated in , highly intense grief reactions were described, albeit primarily by those who had lost their only child or those who had witnessed how their child’s drug use escalated rapidly. These parents also described an enduring overload before death and a high level of rumination after death. They felt emotionally and physically exhausted and described a variety of negative consequences for their physical, mental and social health. Years of discredit and devaluation had left their mark. Along with self-stigma came social isolation and an intense feeling of shame which prevented participation in society for some of the parents. These reactions had lasted for more than six months, alerting us to the possibility of complications in the grieving process.

From the general literature on grief and bereavement and taking into consideration the results from studies on drug-death bereaved, it is possible to make some assumptions about bereavement after DRDs. A theoretical model, ‘The special grief’, describing components of drug-death bereavement has been developed by Dyregrov et al. (Citation2019). Dyregrov et al. (Citation2019) accept that anticipatory grief, in addition to the stress of living with a person who uses narcotics, can contribute to an emotional overload and make the processing of grief more difficult for the bereaved. In line with theories of stigma, the model also incorporates the possibility that those bereaved by DRDs can experience negative attitudes and actions from those around them, such as networks, local communities and support services. In addition, the model integrates the notion of disenfranchized grief among the drug-death bereaved, indicating that experiencing unacknowledged losses could complicate the grieving process. Our study’s findings elaborate on the elements and the dynamic within the described theoretical model by Dyregrov et al. (Citation2019). Accordingly, we identified an extensive overload of emotions and we suggest that the consequences for daily life can be explained in terms of an ‘extended parenthood’ (). Our findings also elaborate on the elements complicated and disenfranchized grief, suggesting that, for these parents, silence from helpers, self-inflicted stigma and complicated interactions with their social networks can increase the risk of complications. In addition, we discuss stigma as a possible reason for lack of help from public services, a result that is a potential factor which is appropriate for further investigation.

Methodological issues

We recognize that multiple realities exist. We have outlined personal experiences and viewpoints that may have resulted in methodological bias, although we have aimed to clearly and accurately present the parents’ perspectives. To improve methodological rigor, we have endeavored a transparent and clear description of the research process from the initial outline through the development of the methods and the reporting of the findings. Reflexive journals were written after each in-depth interview, containing information about our subjective responses to the setting and the participants. In addition, the results section contains key, illustrative, verbatim extracts from the interviews. Describing reflexivity is important to enhance a study’s validity. As recommended in standards for reporting qualitative research (Malterud Citation2001; O’Brien et al. Citation2014), we described the characteristics and the role of the researchers in the paper. We argue that the checklist for reporting standards strengthens the transparency of this study and enhances the transferability of its findings to other contexts. The systematic review by Titlestad et al. (Citation2019) calls for more rigorous studies and, as recommended in this review, we have investigated and described distinctive characteristics such as the deceased’s age, the time since death, whether the next of kin was aware of the drug use, and whether the deceased died after first-time use or drug use over time.

One strength of this study is the wide use of different recruitment strategies. Nevertheless, despite our efforts to recruit bereaved parents from all classes in society, the risk of sampling bias is present, particularly given that people from lower social classes are under-represented. On the other hand, the size of our study sample has sufficient information power, in accordance with Malterud et al. (Citation2016) descriptions.

There are pros and cons in the choice of applying a thematic analysis. Thematic analysis has been described as an ‘anything goes’ approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Majumdar Citation2019, p. 205). Braun and Clarke (Citation2019, Citation2006) have addressed this criticism in recent years, developing guidelines for assessing the quality of qualitative research analysis. We argue that, by following the stages involved in reflexive thematic analysis, we strengthen the quality, transparency and transferability of this study. In addition, the use of thematic analysis enabled us to stay close to the data provided by the participants and thereby remain empirically faithful to the included cases, providing explicit and transparent links between our conclusions and the data material.

Conclusion and implications for practice and policy

The findings of this research project contribute to our understanding of the complexity of drug-death bereavement, and we believe these results will be of interest to bereaved family members and their social networks, as well as professionals in health and welfare services. Hopefully, they will lead to improvements in how we communicate about and relate to DRDs. Show kindness and compassion is also one of five key messages identified from the UK-study by Valentine and colleagues which is described in the guideline Bereaved through substance use: Guidelines for those whose work brings them into contact with adults bereaved after a drug or alcohol-related death (Cartwright Citation2015; Valentine and Bauld Citation2018). The findings from our study hopefully also contribute to an increased awareness and adherence to guidelines that describe how to implement relief measures for drug-death bereaved (e.g. Cartwright Citation2015; Norwegian Directorate of Health Citation2016).

This study set out to explore drug-death bereaved parents’ grief experiences and what help and support they received. The parents experienced a special death and described a special grief. The title of the paper, ‘Sounds of Silence’, refers to the Simon and Garfunkel song ‘The Sound of Silence’ (Simon Citation1964) and characterizes what drug-death bereaved parents go through. The song’s lyrics demonstrate how silence can be perceived: ‘People talking without speaking, People hearing without listening, People writing songs that voices never share, And no one dared, Disturb the sound of silence.’ This silence is reflected in how the parents perceived a silence from helpers when their child was alive. When the child died, the silence from public services was described as deafening. They were not sought out, and the ones who got help had to seek out the services themselves. Self-stigma, which disturbed the dynamics in their communication with others, and the fact that people in the network were perceived as insecure also represented a type of silence. We argue that one of the main findings of this study is that such silence may have the potential to trigger intense suffering, and perhaps even complications in the grieving process, consequences that may be prevented or risks at least lessened, if the words of the bereaved parents expressed in this investigation are heard.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to the bereaved parents for generously sharing their experiences and time.

Disclosure statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Arnett JJ. 2000. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 55(5):469–480.

- Biong S, Sveipe EJ, Ravndal E. 2015. «Alt verker og alt har satt seg fast»: Om pårørendes erfaringer med overdosedødsfall. [“I hurt all over and feel all tied up in knots.” Bereaved experiences with death by overdose]. Tidsskrift psykisk helsearbeid. 12(04):278–287. http://www.idunn.no/tph/2015/04/alt_verker_og_alt_har_satt_seg_fast_om_paaroerendes_erfar.

- Biong S, Thylstrup B. 2016. Verden vaelter: Pårørendes erfaringer med narkotikarelaterede dødsfald. [The world collapses: relatives’ experiences with drug-related deaths. Klinisk Sygepleje. 43(02):75–86.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2019. Thematic analysis: a reflexive approach. https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/our-research/research-groups/thematic-analysis.html

- Cartwright P. 2015. Bereaved through substance use: guidelines for those whose work brings them into contact with adults bereaved after a drug or alcohol-related death. University of Bath. http://www.bath.ac.uk/cdas/documents/bereaved-through-substance-use.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019. Drug overdose deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html.

- Corrigan PW, Kuwabara SA, O’Shaughnessy J. 2009. The public stigma of mental illness and drug addiction. Findings from a stratified random sample. J Soc Work. 9(2):139–147.

- Corrigan PW, Roe D, Tsang HW. 2011. Challenging the stigma of mental illness: lessons for therapists and advocates. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons.

- Corrigan PW, Schomerus G, Smelson D. 2017. Are some of the stigmas of addictions culturally sanctioned? Br J Psychiatry. 210(3):180–181.

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. 2006. The paradox of self‐stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 9(1):35–53.

- da Silva EA, Noto AR, Formigoni MLOS. 2007. Death by drug overdose: impact on families. J Psychoact Drugs. 39(3):301–306.

- Dias N, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Wei H, Boring E, Sewell K, Haase JE. 2019. A systematic literature review of the current state of knowledge related to interventions for bereaved parents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 36(12):1124–1133.

- Doka KJ. 1999. Disenfranchised grief. Bereavement Care. 18(3):37–39.

- Doka KJ. 2002. Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Champaign (IL): Research Press.

- Dyregrov K. 2004. Bereaved parents’ experience of research participation. Soc Sci Med. 58(2):391–400.

- Dyregrov K, Møgster B, Løseth H-M, Lorås L, Titlestad KB. 2019. The special grief following drug related deaths. Addict Res Theory. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16066359.2019.1679122

- Dyregrov K, Nordanger D, Dyregrov A. 2003. Predictors of psychosocial distress after suicide, SIDS and accidents. Death Stud. 27(2):143–165.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction 2019. European drug report 2019: trends and developments. Lisbon (Portugal): EMCDDA. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/edr/trends-developments/2018

- Feigelman W, Feigelman B, Range LM. 2020. Grief and healing trajectories of drug-death-bereaved parents. OMEGA-J Death Dying. 80(4):629–647.

- Feigelman W, Jordan JR, Gorman BS. 2011. Parental grief after a child’s drug death compared to other death causes: investigating a greatly neglected bereavement population. Omega (Westport). 63(4):291–316.

- Goffman E. 1963. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. London (UK): Penguin.

- Grace P. 2012. On track or off the rails? A phenomenological study of children’s experiences of dealing with parental bereavement through substance misuse [unpublished PhD thesis]. Manchester (UK): University of Manchester.

- Greve B. 2007. What characterise the Nordic welfare state model. J Soc Sci. 3(2):43–51.

- Guy P, Holloway M. 2007. Drug-related deaths and the ‘special deaths’ of late modernity. Sociology. 41(1):83–96.

- Heeke C, Kampisiou C, Niemeyer H, Knaevelsrud C. 2017. A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of prolonged grief disorder in adults exposed to violent loss. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 8(sup6):1583524.

- Li J, Laursen TM, Precht DH, Olsen J, Mortensen PB. 2005. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med. 352(12):1190–1196.

- Li J, Precht DH, Mortensen PB, Olsen J. 2003. Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: a nationwide follow-up study. Lancet. 361(9355):363–367.

- Li J, Tendeiro JN, Stroebe M. 2019. Guilt in bereavement: its relationship with complicated grief and depression. Int J Psychol. 54(4):454–461.

- Livingston W. 2017. Alcohol and other drug use. In Thompson N, Cox GR, editors. Handbook of the sociology of death, grief, and bereavement. A guide to theory and practice. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Majumdar A. 2019. Thematic analysis in qualitative research. In: Manish G, Shaheen M, Prathap RK, editors. Qualitative techniques for workplace data analysis. Hershey (PA): IGI Global; p. 197–220.

- Malterud K. 2001. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 358(9280):483–488.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. 2016. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 26(13):1753–1760.

- Maltman K, Savic M, Manning V, Dilkes-Frayne E, Carter A, Lubman DI. 2019. ‘Holding on’ and ‘letting go’: a thematic analysis of Australian parent’s styles of coping with their adult child’s methamphetamine use. Addict Res Theory. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/16066359.2019.1655547

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. 2016. Mestring, samhørighet og håp - Veileder for psykososiale tiltak ved kriser, ulykker og katastrofer. [Psychosocial interventions in the event of crisis, accidents and disasters]. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health. https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/1166/Mestring,-samhorighet-og-hap-veileder-for-psykososiale-tiltak-ved-kriser-ulykker-og-katastrofer-IS-2428.pdf

- Norwegian Directorate of Health. 2019. National strategy for overdose prevention 2019–2022. “Sure, you can quit drugs – but first you have to survive.” Oslo: Norwegian Directorate of Health. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/405ff92c06e34a9e93e92149ad616806/20190320_nasjonal_overdosestrategi_2019-2022.pdf

- Nowak RA. 2015. Parents bereaved by drug related death: a grounded theory study (Doctor of Philosophy Qualitative Study). Minneapolis (MN): Capella University. https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1709243935.html?FMT=AI

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. 2014. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 89(9):1245–1251.

- Oreo A, Ozgul S. 2007. Grief experiences of parents coping with an adult child with problem substance use. Addict Res Theory. 15(1):71–83.

- Orford J, Velleman R, Copello A, Templeton L, Ibanga A. 2010. The experiences of affected family members: a summary of two decades of qualitative research. Drugs Educ Prevent Policy. 17(sup1):44–62.

- Palaganas EC, Sanchez MC, Molintas M, Visitacion P, Caricativo RD. 2017. Reflexivity in qualitative research: a journey of learning. Qual Rep. 22(2):426–438.

- Rando TA. 1986. Loss and anticipatory grief. Lanham (MD): Lexington Books.

- ResearchGate 2019. Drug-death related bereavement and recovery (The END-project). https://www.researchgate.net/project/DRUG-DEATH-RELATED-BEREAVEMENT-AND-RECOVERY-The-END-project

- Robertson R, Bird SM, McAuley A. 2019. Drug related deaths - a wider view is necessary. Addiction. 114(8):1504–1504.

- Simon PF. 1964. The sounds of silence. New York (NY): Columbia Records.

- Song J, Floyd FJ, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Hong J. 2010. Long‐term effects of child death on parents’ health‐related quality of life: a dyadic analysis. Fam Relat. 59(3):269–282.

- Stevenson M, Achille M, Liben S, Proulx M-C, Humbert N, Petti A, Macdonald ME, Cohen SR. 2017. Understanding how bereaved parents cope with their grief to inform the services provided to them. Qual Health Res. 27(5):649–664.

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. 2007. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 370(9603):1960–1973.

- Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H, Boerner K. 2017. Grief is not a disease but bereavement merits medical awareness. Lancet. 389(10067):347–349.

- Templeton L, Ford A, McKell J, Valentine C, Walter T, Velleman R, Bauld L, Hay G, Hollywood J. 2016. Bereavement through substance use: findings from an interview study with adults in England and Scotland. Addict Res Theory. 24(5):341–354.

- Templeton L, Valentine C, McKell J, Ford A, Velleman R, Walter T, Hay G, Bauld L, Hollywood J. 2017. Bereavement following a fatal overdose: the experiences of adults in England and Scotland. Drugs Educ Prevent Policy. 24(1):58–66.

- The World Medical Association 2018. WMA Declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Thompson N, Doka KJ. 2017. Disenfranchised grief. In: Thompson N, Cox GR, editors. Handbook of the sociology of death, grief, and bereavement. A guide to theory and practice. New York (NY): Taylor & Francis.

- Titlestad KB, Lindeman SK, Lund H, Dyregrov K. 2019. How do family members experience drug death bereavement? A systematic review of the literature. Death Stud. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07481187.2019.1649085

- Tysnes IB, Kiik R. 2019. Support on the way to adulthood: challenges in the transition between social welfare systems. Eur J Soc Work. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13691457.2019.1602512

- Valentine C, Bauld L. 2018. Researching families bereaved by alcohol or drugs. In: Valentine C, editor. Families bereaved by alcohol or drugs: research on experiences, coping and support. London (UK): Routledge.

- Valentine C, Bauld L, Walter T. 2016. Bereavement following substance misuse: a disenfranchised grief. Omega (Westport). 72(4):283–301.

- WHO 2020. ICD-11. International Classification of Diseases 11th revision. The global standard for diagnostic health information. 6B42 Prolonged grief disorder. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1183832314