Abstract

Given the major public health issue of substance use in the college environment and among college students, we must improve our understanding of students attempting to resolve substance related issues. Though much of research and policy attention has focused on individual progress according to personal characteristics and experiences, a much broader, theoretically informed understanding based on interpersonal relationships and contextual conditions of the school and society is warranted. Collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) are a system-level intervention that acknowledges the individual in context and seeks to support them and capitalize on their own skills within a safe environment to practice recovery. To ground CRPs as an environmental support targeting emerging adults that can improve student health and well-being, we developed a social-ecological framework that conceptualizes the multifaceted factors that influence them. Specifically, we aimed to understand factors influencing individuals in CRPs through direct and indirect effects. This conceptualization will better inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of these programs. Our theory-driven framework elucidates the multi-level complexity of CRPs and the importance of individual interventions as well as intervention from multiple stakeholder groups.

Background

Approximately 600,000 Americans in recovery from a substance use disorder currently attend college ( SUD - ACHA-NCHA II Citation2019; National Center for Education Statistics Citation2019; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Citation2019 ). Collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) were first established in 1977 at Brown University to support students who were in recovery from an alcohol or other drug use disorder (White and Finch Citation2006). Since then, numerous universities have established CRPs and there has been a four-fold increase (from 29 to 138) since 2013 in the number of programs operating at institutions of higher education across the U.S. (Laudet et al. Citation2015; Association for Recovery in Higher Education Citation2020). The overarching goal of CRPs is to offer support services, resources, community, and programming for students in recovery to ensure they maintain recovery and complete their education (Bugbee et al. Citation2016). These goals are largely achieved through a variety of programs and partnerships that provide wrap-around supportive resources for college students in recovery. Available evidence suggests that students who engage in CRPs perform well in the college environment (Bell et al. Citation2009; Harris et al. Citation2014; Laudet et al. Citation2015; Hennessy et al. Citation2021).

Recently, CRPs have gained the attention of college administrators, health providers, policy makers, and researchers for their direct and indirect benefits on college campuses. Though previous work has aimed to identify core CRP constructs that benefit students (Bell et al. Citation2009; Terrion Citation2013; Whitney Citation2018), efforts to coalesce these findings into a comprehensive conceptual model have yet to be realized. This has led some researchers to call for theory-driven frameworks through which CRPs can be better understood (Vest et al. Citation2021; Hennessy et al. Citation2022). The goal of this manuscript is to provide a better understanding of factors influencing individuals in CRPs through direct (e.g. gender, personality, co-occurring mental health) and indirect (e.g. public policy, housing services, funding) effects.

Overall, CRPs have not yet been examined using rigorous study designs such as randomized controlled trials or prospective cohort studies (Hennessy et al. Citation2018). However, the effectiveness of many – though not all – of their prevalent components have been studied in other populations. These components include peer recovery coaches and mentors (Laudet and Humphreys Citation2013; Eddie et al. Citation2019), continuing care treatment programming (McKay Citation2009), and mutual-help group facilitation (Humphreys Citation2003; Kelly et al. Citation2020). Other components have not been rigorously evaluated, but practice-based evidence suggests that some of these components, such as designated CRP student drop-in centers, are highly utilized among students to support their recovery, providing anecdotal support for their use (Cleveland and Harris Citation2010).

In a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies, Ashford et al. (Citation2018) found evidence of six major themes in the research literature on CRPs: internalized feelings, coping mechanisms, conflict of recovery status, social connectivity, recovery supports, and drop-in recovery centers. These multiple themes highlight one of the difficulties of evaluating CRPs; specifically, that these themes operate at multiple levels spanning personal, contextual, and programmatic dimensions of recovery and recovery supports. Indeed, given that college students are often interacting with a variety of programs and experiences both internal and external to the CRP and the college environment, there is a need to conceptualize CRPs through a theory-driven socio-ecological model (SEM) which can accurately reflect the complexity of CRPs and provide a rigorous conceptual space for hypothesis testing.

The Socio-Ecological model

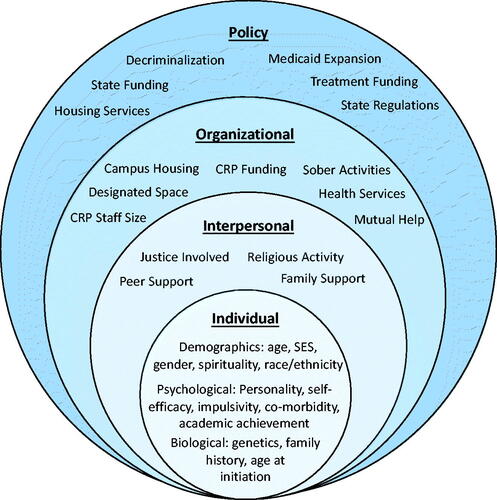

The SEM contends that people are constantly interacting with their surroundings, and over time, they are shaping, and being shaped by, these contextual factors (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977). As such, connecting practices, structure, and outcomes with theoretical assumptions are vital to understanding complex SEMs. These models allow researchers to study components of a problem and understand how the problem can be investigated at multiple levels and among different contexts (Reifsnider et al. Citation2005). According to Bronfenbrenner (Citation1977), the SEM includes risk and protective factors on an individual level (health and personal traits); an interpersonal/relationship level (the closest social circle that contributes to the range of experience); an organization/school/community level (the settings for interaction); and the societal/policy level (social and cultural norms, as well as diverse social policies). Mcleroy et al. (Citation1988) further outlines these context-specific outcomes as variables at the individual, interpersonal, institutional/community, and policy levels (see similar outline in ). While one previous report using an ecological model to understand the CRP at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro exists (Beeson et al. Citation2017), the researchers did not provide a broader perspective more generalizable to the range of CRP programs or identify where current knowledge gaps exist. To create a model relevant to all CRPs and inform current research efforts, a comprehensive SEM is needed.

Aim of this paper

The purpose of this article is to review extant research on CRPs through a SEM framework. Specifically, we aim to situate the CRP as a specific environmental support targeting emerging adults that can improve various aspects of their health and well-being. Further, we aim to better inform the development, implementation, and evaluation of these programs. Developing a more nuanced understanding of CRPs may help researchers, healthcare professionals, state policy makers, and college administrators improve student access to CRP services, evaluate CRP programming, and develop further tailored supports for their student population, which could directly improve individual student outcomes and indirectly reduce stigma of substance use disorders campus-wide. The pragmatic approach of this paper will allow for understanding college students, their recovery, and their engagement in CRPs in a ‘real-world’ context (Brownson et al. Citation2009).

Socio-Ecological model of collegiate recovery programs

The final theoretical SEM of CRPs, shown in , depicts the major characteristics that influence the experience of college students in recovery and in a CRP on four levels: the individual, interpersonal, organizational/community, and policy. Each level adds complexity and must be acknowledged to effectively develop, implement, and evaluate CRP components and interventions. In the following sections, we provide an overview of the current research in each SEM level and how it contributes important nuance to our understanding of the student experience in CRPs. We note that this conceptual SEM project was written in conjunction with a recent scoping review (Vest et al. Citation2021) and much of the extant research cited below was culled from that project.

Individual level

Individual level factors include sociodemographic, personality, mental health, and biological factors. These individual level factors are known to influence substance use and the recovery process, specifically during emerging adulthood (Stone et al. Citation2012).

According to a recent scoping review article, most CRP-related studies report on basic sociodemographic indicators such as sex (85% of studies), race/ethnicity (75%), and age (75%); yet other indicators such as non-binary genders (2%) and sexual orientation (8%) are reported much less often (Vest et al. Citation2021). Very few studies have explicitly examined sex, gender, or race/ethnicity differences in outcomes related to collegiate recovery students (Smith et al. Citation2018; Patterson et al. Citation2021). This is surprising considering the noted differences by sex and racial groups among the general population for substance use in general (Stone et al. Citation2012), binge drinking in college students (Grossbard et al. Citation2016; Krieger et al. Citation2018), and in SUD treatment samples (Zilberman et al. Citation2003; Lewis et al. Citation2018). As well, this paucity of studies examining sex, gender, or race/ethnicity differences in CRP-related outcomes suggests a lack of attention to the nuances of different experiences by membership in multiple marginalized identities (e.g. intersectionality) (Cole Citation2009).

Psychological factors are believed to play a substantial role in recovery outcomes among college students. For example, studies have found a high level of psychiatric comorbidities (Laudet et al. Citation2015; Ashford et al. Citation2018; Citation2019; Odefemi-Azzan Citation2020; Nichols et al. Citation2021) and poly-substance use disorders (Cleveland et al. Citation2007; Laudet et al. Citation2015) among CRP students. Research on college students in recovery has demonstrated that students with more severe mental health issues have a higher prevalence of return to substance use and decreased graduation rates than students with less severe mental health issues (Odefemi-Azzan Citation2020). Furthermore, increased self-stigma beliefs were associated with decreased quality of life, increased anxiety/depression symptoms, and decreased expectations of finding a job after graduation (Watts et al. Citation2019).

Biological and physiological factors are important to consider, such as genetic liability, withdrawal potential, family history, age of initiation (of substances), and physical health or chronic pain. Thus far, these potential factors have been largely ignored in the CRP literature. This is in spite of a proliferation of molecular, neurochemical, and physiological research on substance use disorder in both humans and animal models in recent decades.

Lastly, course performance and academic achievement represent a potential bi-directional individual level variable, as they can be both a cause and a consequence of substance use/relapse risk among college students (Baer Citation2002). That is, students can experience stress, leading to reduced coping and increased tendency to use substances to cope, especially during periods of high academic pressure (i.e. mid-terms and finals). In studies that have examined college students, those who consider themselves in recovery are able maintain a higher grade point average when compared to other student groups, suggesting they are actively using coping strategies other than substance use to address the academic stressors of college (Moore Citation1999; Cleveland et al. Citation2007; Botzet et al. Citation2008; Laudet et al. Citation2015).

In this section, we have noted some of the key individual level factors which may be important for college students in recovery. However, this list is by no means comprehensive. Many individual level characteristics can also play a role in how well individuals respond to interventions. Some unexplored individual factors among this population, but examined in other youth/adult recovery populations, include self-efficacy, mental health, emotion regulation, and impulsivity (Quirk Citation2001; Littlefield et al. Citation2010; Russell et al. Citation2017; Hennessy et al. Citation2018; Tran et al. Citation2018; Grazioli et al. Citation2021). Overall, there is a strong need for more research on these and other individual level psychosocial and biological factors among college students in recovery.

Interpersonal level

Family, peers, social events, and CRP staff interactions shape the beliefs, perspectives, and behaviors of students in recovery. Studies examining interpersonal relationships and social support outcomes are common in the CRP literature. For example, Bell et al. (Citation2009) asked CRP students to self-report their reasons for remaining enrolled in college and found that feeling safe and being a part of a community where strong friendships could be made were vital. Additionally, the students in the study reported that staff support, campus-based recovery meetings, and informal interaction with peers in recovery were important components of the program (Bell et al. Citation2009). Membership in a CRP has been reported to create a web of social support, which enables constant contact with peers in recovery and results in better handling of challenges to student recovery (Cleveland and Groenendyk Citation2010). Indeed, the more network connections within the CRP a person had was directly related to longer time since a person’s last use of substances/relapse (Smith et al. Citation2018); among CRP alumni, social support and peer accountability were reported as instrumental in their recovery (Lovett Citation2015). Yet, these differences may vary by gender. For example, social support was related to a decreased risk of relapse among women but an increased risk of relapse among men in a CRP (Patterson et al., Citation2021).

Family support in regard to substance use disorder and dysfunctional family systems can influence college students in recovery through environmental mechanisms and the existing literature provides a complex picture of both supportive and unsupportive family backgrounds of CRP students. One study of existing CRP data found that across two sites, approximately 40% of students reported a family history of addiction (Hennessy et al. Citation2021). In a study examining family dynamics, Cleveland et al. (Citation2007) found that over half of students belonging to a CRP (53.7%) came from homes where both custodial parents were currently married (to each other), and had scores on a family dynamics measure that were in line with a comparable non-clinical sample, while a clinical comparison sample was 10% higher. Research on the influence of family relationships among CRP students is abundant in literature. For example, one study of college students returning to college after SUD treatment (not in a formal CRP) found that follow-up care reduced family problems (Bennett et al. Citation1996). Likewise, Shumway et al. (Citation2013) found that family functioning was improved in students attending a CRP after treatment compared to those not in a CRP. Similarly, a study examining students in recovery reported changes in the quality of their relationships with family were common as a result of their recovery (Iarussi Citation2018). Lastly, aiming to target familial influence, the Center for the Study of Addiction and Recovery at Texas Tech University has created a family program intended to include the family dynamic as part of the students’ post-treatment plan (Shumway et al. Citation2011).

Events hosted by the CRP and interactions or personal relationships with the CRP staff can also influence students at the interpersonal level. Staff-run seminars on SUD and recovery-related topics increase social support and offer a strong supplement to CRP student mutual-help meetings (Casiraghi and Mulsow Citation2010). Another study examined CRP student employees’ self-reported roles and found that offering one-on-one individual support and strategic planning for students in recovery were regarded as examples of where their role as students helped them connect in meaningful ways (Gueci, Citation2018).

In sum, recovery theory positing that recovery is essentially a social process (Beckwith et al. Citation2019; Kay and Monaghan Citation2019) as well as the findings reported in this section point to the importance of interpersonal processes and outcomes for students in CRPs and the need to build upon this growing evidence base.

Organizational/community level

The third level of the SEM represents the organizational and community settings of a CRP, which is housed in its own unique ecosystem of a college/university environment. These community-level influences provide an important context to individual recovery and may affect the entire student population at a given college. The various aspects of these community-level resources and culture, such as linkages with health services and academic support, campus/community stigma, scholarships, CRP resources influencing programming (i.e. funding, staff size, designated space, department where the CRP is housed), non-drug and alcohol-related activities, campus-based recovery housing, campus mutual-help meetings, and are major factors that can impact CRPs.

Having a designated space for the CRP, such as through a CRP drop-in center, can offer students a physical communal space for recovery-related accommodations and services (Bell et al. Citation2009). Drop-in centers vary in size and services offered but their primary goal is to serve as a ‘one-stop center’ for information on recovery offerings on campus. They represent an important step in CRP evolution because drop-in centers for other educational programs have yielded overwhelmingly positive outcomes (Imamoto Citation2006). In a meta-synthesis on CRPs, Ashford et al. (Citation2018) found that the CRP drop-in center was identified as a core component among CRP students. In addition, Cleveland and Harris (Citation2010) found that student conversations at a CRP drop-in center reduced student craving and negative affect. Though no controlled trials on CRP drop-in centers have been undertaken, anecdotal and practice-based reports support the use of these highly valued campus-based resources.

Stigma surrounding people with substance use disorders has hindered progress in treatment and recovery of individuals with substance use disorder (ROOM Citation2005; Livingston et al. Citation2012). Stigma has been examined often in the CRP literature and recovery ally training has been developed to directly address the culture around recovery on a college campus (Spencer Citation2017; Gueci, Citation2018; Beeson et al. Citation2019). These investigations report reductions in student and staff level stigma due to recovery ally trainings; however, no studies to date have looked at the stigma reported among students and staff at schools with and without a CRP. Studies that can examine differences in school-wide attitudes are needed in the CRP literature. These studies can offer support for CRPs as an asset at the community level for their ability to reduce harmful stigma and normalize the experience of having a substance use disorder for college students not in recovery.

Community-level resources surrounding the college may also be a critical factor for CRPs. For example, the number of off-campus mutual-help meetings and local recovery housing (e.g. Oxford Houses) resources could have a significant impact on student recovery outcomes. Additionally, access to and assertive linkage between CRPs and local treatment programs may be crucial to CRPs to remain viable at community colleges and other small universities.

Policy level

There are many factors affecting CRPs, and in turn, college students in recovery and the CRP community, that are shaped by the larger context of US state and federal policy. These policies encompass universities’ government relations, law enforcement, drug decriminalization, higher education regulations, treatment funding, access to housing services, and state budget priorities. National policy directly supporting the infrastructure and evaluation of CRPs may be important considering the recent interest in characterizing students in recovery internationally (Byrne et al. Citation2022) and the growing interest in CRPs in the United Kingdom (i.e. both Teesside University and University of Birmingham have instituted CRPs in the past 5 years).

CRP funding at the federal level has generally been secured through initiatives from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration or the Department of Education. Likewise, a nonprofit funder, the Stacy Mathewson Foundation, provided pilot grants for schools initiating CRPs from 2015-2018. Most notable is the considerable lack of NIH/NSF funded CRP research initiatives. In fact, only one small study (NIDA R21 funding mechanism) has been previously backed by the NIH (Laudet et al. Citation2015) prior to 2022Footnote1. Ideally this will improve with the emerging efforts to address research on recovery and addiction recovery support services now being championed by both the NIDA and the NIAAA (Hagman et al. Citation2022). Hence, to effectively evaluate the impact of CRPs nationwide, a considerable emphasis will need to be placed on high-impact NIH/NSF funded research with a specific focus on beginning to address causal mechanisms of CRPs through rigorous longitudinal designs.

State-level funding for CRPs is neither mandated nor widely available across the US. Notable exceptions in states that have created budget line items or other funding mechanisms for CRPs include Utah, Washington, and North Carolina. Though one study examined reductions in stigma related to a recovery ally training which was a part of state level funding in North Carolina (Beeson et al. Citation2017), no studies have examined the comprehensive impact of state-level funding. The lack of state-level research is critical because much of the funding in higher education is secured as a result of state-level legislation and budget setting.

Additional policy level factors likely influencing CRPs and their student members include local law enforcement tactics that may drive college administration rules and disciplinary proceedings (targeting of low-level drug/alcohol possession and utilization of drug courts), decriminalization (of drugs like marijuana and psychedelics), and access to affordable housing services (Oxford House availability or school sponsored substance free housing alternatives). Lastly, state-level policies relating to SUD treatment reimbursement and availability may also be important for CRP student transitioning from those service providers.

Conclusions

The primary goal of this paper was to explore the extant literature on CRPs through an SEM framework. We must highlight that CRPs operate in an ever-evolving landscape of recovery (Best and Ivers Citation2022) and higher education (Staley and Trinkle Citation2011), which requires a multi-faceted approach and the consideration of many stakeholders. The complex interactions of contributing factors (at all SEM levels) relating to college student recovery have been shaped across time through policies and available research. Though we have structured our framework by contrasting the individual, interpersonal, organizational/community, and policy contexts, we also note that there is substantive connectedness within these contexts. However, the ultimate utility of the SEM we propose is to investigate the multi-directional links among the factors that contribute to student success in the recovery phase of the disease of addiction and the impact of CRP implementation strategies, as well as the potential positive influence of the CRP on its local community and beyond (Best and Ivers Citation2022).

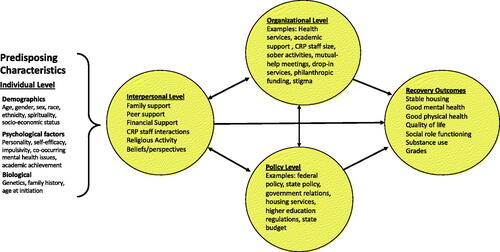

Further, we propose the conceptual diagram provided in as a framework to inform CRP research designs in future studies where appropriately nested analyses (e.g. multi-level) regression, path, and mixture model analyses, can test bi-directional relationships between these concepts. A straightforward example may include a project predicting quality of life outcomes from the different types of social support that CRPs offer. Taking it one step further, a moderation analysis could be computed with peer support and family support predicting a quality-of-life measure (e.g. SF-36) individually and then computing the synergistic effect of both (moderating effect) on quality of life. The model will also serve as a framework for qualitative, mixed-method, and implementation science focused CRP projects. As research continues to evolve regarding CRPs, the framework is intended to inform testable hypotheses, which can be proposed and investigated. As a result, the framework we propose will be further refined to inform policy and research at each SEM level.

Ethical approval

The research in this paper does not require ethics board approval.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Keith Humphreys and Dr. Christine Timko for their early feedback on this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Noel Vest

Noel Vest, PhD is an Assistant Professor at the Boston University School of Public Health. Dr. Vest’s research interests include the intersection of mental health, substance use disorders, addiction recovery, pain, and prison reentry.

Emily Hennessy

Emily A. Hennessy, Ph.D. is a member of the Faculty with Harvard Medical School and Associate Director of Biostatistics at the Recovery Research Institute. Dr. Hennessy’s research examines factors associated with health behavior change among adolescents.

Sierra Castedo de Martell

Sierra Castedo de Martell, is a doctoral candidate at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health.

Rebecca Smith

Rebecca Smith, is a doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University. Rebecca’s research interests broadly include risk and resiliency in adolescents and young adults.

Notes

1 We note the first author of this manuscript was awarded a K01 early career award through the National Institute on Drug Abuse in March of 2022 to study collegiate recovery.

References

- ACHA-NCHA II 2019. Undergaduate Student Reference Group Data Report Spring 2019. American College Health Association, 1–60. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_UNDERGRADUATE_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf

- Ashford RD, Brown AM, Curtis B. 2018. Collegiate Recovery Programs: The Integrated Behavioral Health Model. Alcohol Treatment Q. 36(2):274–285.

- Ashford RD, Brown AM, Eisenhart E, Thompson-Heller A, Curtis B. 2018. What we know about students in recovery: meta-synthesis of collegiate recovery programs, 2000-2017. Addi Res Theory. 26(5):405–413.

- Ashford RD, Wheeler B, Brown AM. 2019. Collegiate recovery programs and disordered eating: exploring subclinical behaviors among students in recovery. Alcohol Treatment Q. 37(1):99–108.

- Association for Recovery in Higher Education 2020. ARHE - Standards and Recommendations. https://collegiaterecovery.org/standards-recommendations/

- Baer JS. 2002. Student factors: understanding individual variation in college drinking. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. (s14):40–53.

- Beckwith M, Best D, Savic M, Haslam C, Bathish R, Dingle G, Mackenzie J, Staiger PK, Lubman DI. 2019. Social Identity Mapping in Addiction Recovery (SIM-AR): extension and application of a visual method. Addict Res Theory. 27(6):462–471.

- Beeson ET, Ryding R, Peterson HM, Ansell KL, Aideyan B, Whitney JM. 2019. RecoveryZone: a pilot study evaluating the outcomes of an online ally training program. J Stud Affairs Res Pract. 56(3):284–297.

- Beeson ET, Whitney JM, Peterson HM. 2017. The development of a collegiate recovery program: applying social cognitive theory within a social ecological framework. Am J Health Educ. 48(4):226–239.

- Bell NJ, Kanitkar K, Kerksiek KA, Watson W, Das A, Kostina-Ritchey E, Russell MH, Harris K. 2009. It has made college possible for Me”: Feedback on the impact of a university-based center for students in recovery. J Am Coll Health. 57(6):650–7657.

- Bennett ME, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Paulus MD. 1996. An intensive program for collegiate substance abusers: progress six months after treatment entry. J Subst Abuse Treat. 13(3):219–225.

- Best D, Ivers J-H. 2022. Inkspots and ice cream cones: a model of recovery contagion and growth. Addict Res Theory. 30(3):155–161.

- Botzet AM, Winters K, Fahnhorst T. 2008. An exploratory assessment of a college substance abuse recovery program: Augsburg College’s StepUP program. J Groups Addict Recovery. 2(2-4):257–270.

- Bronfenbrenner U. 1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 32(7):513–531.

- Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. 2009. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 30:175–201.

- Bugbee B. A, Kimberly Caldeira MM, Andrea Soong MM, Kathryn Vincent MB, Amelia Arria MM. 2016. Collegiate recovery programs: a win-win proposition for students and colleges about the center on young adult health and development suggested citation. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21549.08160

- Byrne M, Dick S, Ryan L, Dockery S, Ivers J-H, Linehan C, Vasiliou V. 2022. The Drug Use in Higher Education in Ireland (DUHEI) Survey 2021: Main Findings. http://www.duhei.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/duhei21.pdf

- Casiraghi AM, Mulsow M. 2010. Building support for recovery into an academic curriculum: student reflections on the value of staff run seminars. In: H. Cleveland, K. Harris, & R. Wiebe, editors. Substance abuse recovery in college: Community supported abstinence 1st ed. Boston, MA: Springer. p. 113–144.

- Cleveland HH, Harris K. 2010. Conversations about recovery at and away from a drop-in center among members of a collegiate recovery community. Alcohol Treatment Q. 28(1):78–94.

- Cleveland HH, Harris KS, Baker AK, Herbert R, Dean LR. 2007. Characteristics of a collegiate recovery community: Maintaining recovery in an abstinence-hostile environment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 33(1):13–23.

- Cleveland H, Groenendyk A. 2010. Daily lives of young adultmembers of a collegiate recovery community. In: H. H. Cleveland, K. S. Harris, & R. P. Wiebe, editors. Substance abuse recovery in college: community supported abstinence. 1st ed. Boston, MA: Springer. p. 77–96.

- Cole ER. 2009. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 64(3):170–180.

- Eddie D, Hoffman L, Vilsaint C, Abry A, Bergman B, Hoeppner B, Weinstein C, Kelly JF. 2019. Lived experience in new models of care for substance use disorder: a systematic review of peer recovery support services and recovery coaching. Front Psychol. 10:1052.

- Grazioli VS, Studer J, Larimer ME, Lewis MA, Bertholet N, Marmet S, Daeppen J-B, Gmel G. 2021. Protective behavioral strategies and alcohol outcomes: impact of mood and personality disorders. Addict Behav. 112:106615.

- Grossbard JR, Mastroleo NR, Geisner IM, Atkins D, Ray AE, Kilmer JR, Mallett K, Larimer ME, Turrisi R. 2016. Drinking norms, readiness to change, and gender as moderators of a combined alcohol intervention for first-year college students. Addict Behav. 52:75–82.

- Gueci N. 2018. Collegiate Recovery Program (CRP): student needs and employee roles. BHAC. 2(2):33.

- Gueci V. 2018. Recovery 101: providing peer-to-peer support to students in recovery. Arizona State University. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2154427635

- Hagman BT, Falk D, Litten R, Koob GF. 2022. Defining recovery from alcohol use disorder: development of an NIAAA research definition. AJP. 1–6.

- Harris KS, Kimball TG, Casiraghi AM, Maison SJ. 2014. Collegiate recovery programs. Peabody J Educ. 89(2):229–243.

- Hennessy EA, Nichols LM, Brown TB, Tanner-Smith EE. 2022. Advancing the science of evaluating collegiate recovery program processes and outcomes: a recovery capital perspective. Eval Program Plann. 91:102057.

- Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith EE, Nichols LM, Brown TB, Mcculloch BJ. 2021. A multi-site study of emerging adults in collegiate recovery programs at public institutions. Soc Sci Med. 278:113955.

- Hennessy EA, Tanner‐Smith EE, Finch AJ, Sathe N, Kugley S. 2018. Recovery schools for improving behavioral and academic outcomes among students in recovery from substance use disorders: a systematic review. Campbell System Rev. 14(1):1–86.

- Humphreys K. 2003. Circles of recovery. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511543883

- Iarussi MM. 2018. The experiences of college students in recovery from substance use disorders. J Addict Offender Counsel. 39:46–62.

- Imamoto B. 2006. Evaluating the drop-in center. Public Services Q. 2(2-3):3–18.

- Kay C, Monaghan M. 2019. Rethinking recovery and desistance processes: developing a social identity model of transition. Addict Res Theory. 27(1):47–54.

- Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M, Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group 2020. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 3(3):CD012880.

- Krieger H, Young CM, Anthenien AM, Neighbors C. 2018. The epidemiology of binge drinking among college-age individuals in the United States. Alcohol Res Curr Rev. 39(1):23–30.

- Laudet AB, Harris K, Kimball T, Winters KC, Moberg DP. 2015. Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs: a national survey. J Subst Abuse Treat. 51:38–46.

- Laudet A, Humphreys K. 2013. Promoting recovery in an evolving policy context: what do we know and what do we need to know about recovery support services? J Subst Abuse Treat. 45(1):126–133.

- Lewis B, Hoffman L, Garcia CC, Nixon SJ. 2018. Race and socioeconomic status in substance use progression and treatment entry. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 17(2):150–166.

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Steinley D. 2010. Developmental trajectories of impulsivity and their association with alcohol use and related outcomes during emerging and young adulthood i. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 34(8):1409–1416.

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. 2012. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction. 107(1):39–50.

- Lovett J. 2015. Maintaining lasting recovery after graduating from a collegiate recovery community. University of Alabama. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1762025608

- McKay JR. 2009. Continuing care research: what we have learned and where we are going. J Subst Abuse Treat. 36(2):131–145.

- Mcleroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 15(4):351–377.

- Moore M. 1999. An archival investigation of factors impacting a substance-abuse intervention program. Texas Tech University. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1762025608

- National Center for Education Statistics 2019. Digest of education statistics: 2018. NCES, 2020–009, 1–3. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/ch_3.asp

- Nichols LM, Hennessy EA, Brown TB, Tanner-Smith EE. 2021. Co-occurring mental and behavioral health conditions among collegiate recovery program members. J Am College Health. 1–8.

- Odefemi-Azzan O. 2020. Factors that affect students enrolled in a midsize collegiate recovery program in the United States. Saint Peter’s University. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2417032105

- Patterson MS, Russell AM, Nelon JL, Barry AE, Lanning BA. 2021. Using social network analysis to understand sobriety among a Campus Recovery Community. J Stud Affairs Res Pract. 58(4):401–416.

- Quirk SW. 2001. Emotion concepts in models of substance abuse. Drug Alcohol Rev. 20(1):95–104.

- Reifsnider E, Gallagher M, Forgione B. 2005. Using ecological models in research on health disparities. J Prof Nurs. 21(4):216–222.

- ROOM R. 2005. Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 24(2):143–155.

- Russell BS, Heller AT, Hutchison M. 2017. Differences in adolescent emotion regulation and impulsivity: a group comparison study of school-based recovery students. Subst Use Misuse. 52(8):1085–1097.

- Shumway ST, Bradshaw SD, Harris KS, Baker AK. 2013. Important factors of early addiction recovery and inpatient treatment. Alcohol Treat Q. 31(1):3–24.

- Shumway ST, Kimball TG, Dakin JB, Baker AK, Harris KS. 2011. Multifamily groups in recovery: a revised multifamily curriculum. J Family Psychother. 22(3):247–264.

- Smith JA, Franklin S, Asikis C, Knudsen S, Woodruff A, Kimball T. 2018. Social support and gender as correlates of relapse risk in collegiate recovery programs. Alcohol Treat Q. 36(3):354–365.

- Spencer KM. 2017. Voices of recovery: an exploration of stigma experienced by college students in recovery from alcohol and/or other drug addiction through photovoice. University of North Carolina at Greensboro. http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Spencer_uncg_0154D_12345.pdf

- Staley D, Trinkle D. 2011. The changing landscape of higher education. Educuse Rev. 46:15–34.

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. 2012. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav. 37(7):747–775.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54. 170:51–58.

- Terrion JL. 2013. The experience of post-secondary education for students in recovery from addiction to drugs or alcohol: Relationships and recovery capital. J Soc Personal Relationships. 30(1):3–23.

- Tran J, Teese R, Gill PR. 2018. UPPS-P facets of impulsivity and alcohol use patterns in college and noncollege emerging adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 44(6):695–704.

- Vest N, Reinstra M, Timko C, Kelly J, Humphreys K. 2021. College programming for students in addiction recovery: A PRISMA-guided scoping review. Addict Behav. 121(May):106992.

- Watts JR, Tu W, O'Sullivan D. 2019. Vocational expectations and self-stigmatizing views among collegiate recovery students: an exploratory investigation. J College Counsel. 22(3):240–255.

- White WL, Finch AJ. 2006. The recovery school movement: its history and future. Counselor. https://www.chestnut.org/resources/ced99b10-65df-4522-8800-0b09617cdce3/2006-The-Recovery-School-Movement.pdf

- Whitney J. 2018. Students’ lived experiences in collegiate recovery programs at three large public research universities. Pennsylvania State University. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2207526132

- Zilberman ML, Tavares H, Blume SB, El-Guebaly N. 2003. Substance use disorders: sex differences and psychiatric comorbidities. Can J Psychiatry. 48(1):5–13.