Abstract

This paper presents selected findings from a larger qualitative study in which 18 people recovering from an alcohol use disorder (AUD) were interviewed about maintaining long-term sobriety. The research adopted Personal Construct Psychology (PCP) as its theoretical framework. PCP focuses on personal meanings, particularly within role relationships with significant others. The findings extend our understanding of ‘social support’ from significant others in recovery from AUDs, and may be applicable to other Substance Use Disorders. In line with previous research, participants reported valuing practical support and general encouragement from family, friends and work colleagues. However, participants also reported changes in their sense of self, and especially valued instances where their significant others accepted and endorsed their new ‘sober selves’. Participants reported that their recovery was made more difficult when significant others failed to validate their new selves, or continued to endorse their old drinking identities, and the findings are discussed in terms of the PCP concept of ‘validation’. It is recommended that self-help groups provide opportunities for those recovering from AUDs to ‘practise’ and gain validation for their new, sober selves, and that they provide information and advice to significant others about the potential importance of validation in recovery.

Introduction

The importance of social support in recovery from addictions, including addiction to alcohol, has been well documented. Social support may take a variety of forms, such as membership in formal and informal peer support groups as well as the practical and emotional support provided by family and friends. Lower levels of social support can affect the chances of a person entering treatment for an alcohol use disorder (AUD) and subsequently maintaining sobriety (Mericle, Citation2014; Mowbray et al. Citation2014; Tracey and Wallace Citation2016; Brooks et al. Citation2017) social support from family members has been related to treatment compliance, a positive treatment outcome, less relapse and more days remaining abstinent (Beattie Citation2001; Zywiak et al. Citation2002), and relationships within the work environment are likewise influential (Klingemann Citation1992; Moos and Moos, Citation2007). Negative behaviors from friends and family such as withdrawing from the drinker, family conflict and criticism can lead to relapse (Ellis et al. Citation2004).

Additionally, it has been suggested that the development of a positive recoveree identity is crucial (Laudet et al. Citation2002; Laudet Citation2007; Longabaugh et al. Citation2010; Best et al. Citation2014, Citation2018). Dingle et al. (Citation2015) found that drug and alcohol recoverees experienced their addiction and recovery in terms of their relationships and social identities. Their findings led them to develop the Social Identity Model, arguing that identity change may be a key feature of recovery from SUDs. They argue that changing one’s identity from ‘addict’ to ‘recoveree’ is important for achieving successful outcomes, whether recoverees are aspiring to new social identities or to recovering those previously lost through addiction.

Relationships that facilitate identity change are thought to be key–support from significant others in particular - but relatively little research specifically exploring this has been conducted with those who have maintained long-term sobriety. Hill and Leeming (Citation2014) explored how people recovering from addiction to alcohol felt about how others perceived and behaved toward them. Whilst participants struggled to resist the stigmatizing identity of ‘alcoholic’, they made efforts to develop a new and more valued identity as an ‘aware alcoholic self’.

The findings presented here extend our understanding in this area by applying the theoretically- grounded concept of ‘validation’ to data collected as part of a larger PhD study in which people recovering from alcohol addiction were interviewed about how they had achieved and maintained sobriety (Westwell, Citation2021). The concept of validation may be a useful adjunct to the Social Identity Model as extends our understanding of how social networks can foster (or damage) recoverees’ attempts to develop new and beneficial social identities.

Theoretical framework

The research adopts Personal Construct Psychology (PCP, Kelly Citation1955) as its theoretical framework. PCP is a Constructivist approach and, as such, it makes the fundamental assumption that people’s conduct should be understood as arising from the meaning they draw from their experiences and from the representations of the world they thereby construct for themselves. The findings are interpreted using the PCP concept of ‘validation’. PCP has a long history in psychotherapy, where it has successfully been used to help people through personal change in a variety of contexts (Winter and Viney Citation2005). In line with the theory and research discussed above, PCP likewise emphasizes the role of a sense of self in effecting change and therefore provides an appropriate framework for this research.

Kelly proposed that the ways a person ‘construes’ themselves and their experiences are central to understanding their problems. The person’s ‘core constructs’, the constructs they hold about themselves and which provide them with their sense of self, are especially important. Our constructs are constantly being ‘put to the test’ by us through our conduct, as we seek validation for our construal - without this, our capacity to maintain our sense of self is challenged. Through their behavior toward us, others validate our fundamental self-concept. Personal change means learning to construe oneself differently; in the context of addiction, it, therefore, depends upon being able to develop a new sense of self as a person that is no longer an addict. This new sense of self is reinforced by validation from others, and a person may struggle to achieve change due to ‘a lack of validating of some of their core constructs’ (Button Citation1996, p. 143).

Method

This research aimed to gain in-depth accounts of achieving and maintaining sobriety in a sample of people recovering from alcohol addiction. Semi-structured interviews were chosen, in order to encourage the collection of rich data while allowing the researcher the flexibility to pursue unanticipated routes of enquiry important to participants. Participants gave informed consent, and ethical approval was given by the University of Huddersfield School of Human and Health Sciences Research Ethics and Integrity Panel.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from an Alcohol Advisory Service based in the north of England, consisting of four self-help groups. This Service was set up as a registered charity funded by a Primary Care Trust, and is independent of other self-help groups provided by, for example, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA). The service was initiated by a local hospital-based consultant psychiatrist who had a particular interest in helping people who wanted to achieve sobriety. He attended some early meetings to offer general support and advice to the groups and offer specialist medical input where appropriate. Subsequently, the groups continued with various members acting as their chairs. All the chairs have had their own issues with alcohol and may offer their experience to the group for help and advice.

Each meeting is relatively unstructured when compared to AA meetings, with no prayers or references to ‘the big book’. Meetings usually last for approximately an hour. The chair simply asks the group if there is anything they wish to share, and any attendee can raise an issue; sometimes a person’s contribution may be minimal, such as “Thanks, I appreciate everyone’s help last week’ or it may take up a large proportion of the meeting. Attendees can interject, giving advice and comments, often leading to a more general discussion of an issue a member has introduced. The group and its meetings are advertised in the local newspapers and anyone can attend.

The Alcohol Advisory Service provided two groups in each of the two geographical areas of the borough involved (North and South). These areas had elements of economic deprivation and unemployment and a relatively high south-east Asian population. Approximately 15 people attended each group on a weekly basis. At the time of recruitment, there were no ethnic minority attendees in any of the four groups. Attendees were all at different stages of overcoming their AUD and ranged in age from being in their 20s to their 80s.

Access to the Service was facilitated by the first author, who had used the service 15 years previously. A letter requesting permission to speak to the groups was made to the organisation’s Chairperson, who acted as its key gatekeeper. To recruit participants, the first author attended meetings of the four self-help groups run by the Service in the North and South areas, provided information sheets and described the proposed research, and answered any questions. To encourage trust and acceptance he shared with them his experience of his own recovery from alcohol addiction. He also shared his past work as a psychiatric nurse and as a social worker often working with alcohol recovery organizations.

Sampling and participants

Participants self-defined as previously having difficulties with alcohol for at least 5 years and as having since remained sober for at least one year (Ye et al. 2009). Eighteen people (11 men and 7 women between the ages of 30 and 79 see ) who agreed to participate were still attending group meetings at the time of the interview. Most were living with a partner or dependent and had one or more children. Just over half were in paid employment. The majority reported they had started drinking before the age of 18, often before age 15, and almost all reported a history of relapse. They had received help from a range of support services, including their General Practitioner (GP), Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and counselling. Their reported current abstinence periods were between 2 and 10 years, with a mean of 6.19 years.

Table 1. Gender and age breakdown of participants.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted on the Alcohol Advisory Service’s premises. The interview began with the question: ‘Can you tell me your particular story of how you have achieved sobriety and how you have maintained that change?’ This invited the participant to tell their story from their own perspective, and further supplementary questions were asked as necessary to probe for experiences relating to, for example, the role of others in the person’s attempts to change, significant turning points in their journey, their self-construal and their perceptions of others’ construal of their changes:

Have you tried to change in the past?

Why do you feel this wasn’t successful?

What made you think you needed to change?

Why previous giving up methods, if any, have you tried and haven’t worked?

Was your change planned or unplanned?

Do you feel anyone/thing helped or hindered your change in lifestyle?

Do you feel there was a turning point?

What did these events mean to you?

What did you envisage was going to happen if you didn’t change?

What does your change in lifestyle mean to you?

What do you feel it means to other people?

How do you now imagine your life in five years-time?

How do you imagine other people will view you in five years-time?

How do you feel you have managed to maintain the changes you have made?

Did you need help in order to maintain these changes?

The interviews were carried out by the first author, audio-recorded and later transcribed. He disclosed to participants that he himself was recovering from alcohol addiction in order to establish trust and rapport and encourage openness. All participants were assigned a pseudonym.

Data analysis

The data were thematically analyzed using Template Analysis (TeA) (King, Citation2012). TeA is not aligned with any particular theoretical or epistemological approach and is especially helpful when handling large quantities of qualitative data (Brooks et al. Citation2015). It was therefore deemed appropriate in this case. TeA uses a structured, hierarchical coding system; coding is carried out by developing an initial template based on a small sample of the interview transcripts. This is then applied to each remaining transcript in turn and adjusted to accommodate the data. Fifteen iterations of the template were thereby produced. The first author conducted the analysis, and this was regularly discussed with and quality-checked by the other two authors who read transcripts, discussed the coding of suitable quotes from these and scrutinized each of the 15 iterations of the template. In the weeks following their interview, the advice sessions offered opportunities for participants to discuss their interview with the first author and ask any further questions. Participants were not consulted specifically about the themes emerging from the data; Thomas (Citation2017) argues that member checking does not necessarily enhance the credibility or trustworthiness of qualitative data.

There is a need to reflect on the research process, particularly during analysis, to ensure the researcher’s own experiences and perceptions do not unduly influence the interpretation of the data. It is acknowledged in qualitative research that the researcher’s own past experiences and personal biography necessarily inflect their research. However, the concept of ‘bias’ is typically deemed inappropriate in qualitative research, and according to Braun and Clarke (Citation2023):

Subjectivity is embraced as not just a necessary component of, but a resource for, qualitative research. The researcher’s task is not to ‘manage’ a problem but to explore and understand how they are shaping their analytic engagement, potentially delimiting the analysis through (non-examined) assumptions and positionalities. (p. 6)

Findings

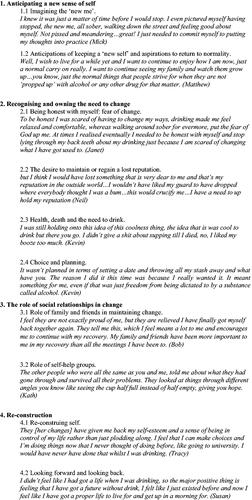

Four main themes were derived from the analysis: (i) Anticipating a new sense of self, (ii) Recognizing and owning the need to change, (iii) The role of social relationships in change and (iv) Reconstruction. . shows the final list of themes and sub-themes, with illustrative quotes.

Here, we present findings relating to one particularly enlightening aspect of sub-theme 3.1: Family and friends validating or not validating ‘the new sober me’. The other aspects of this sub-theme covered issues that have previously been well-documented in the literature such as family and friends providing practical help and participants being motivated to change due to not wanting to ‘let down’ those who have supported them. Although it might be argued that these could be seen as forms of validation, they are not as relevant to the issues concerning social identity that are the focus of this paper. Some of the other themes emerging from the analysis were also relevant to the issue of personal identity, such as ‘anticipating a new sense of self’ and ‘reconstruction’. However, these themes were also substantial and it was decided that, to do justice to the data, the present paper would focus on the single issue of validation.

All participants valued encouragement and support from their family, friends and work colleagues. Participants were not asked directly about validation, however, approximately three-quarters of them explicitly reported experiences suggesting that others either validated and endorsed their ‘new self’ or resisted it. The latter was sometimes perceived by participants as making it more difficult for them to maintain change. Below, we explore the various aspects of validation (and the lack of it) they reported.

The desire for acceptance and validation

Participants demonstrated a desire for acceptance of their changes by significant others and validation of their new self. There is a wistfulness in the responses from Tony and Frances, who, for different reasons, appeared to have an unfulfilled desire for validation. Tony, who had no close relatives since his wife died, says:

It’s a pity I don’t have somebody close to me at times because I miss getting any kind of praise for doing well. I don’t mean I want people to worship me, just some kind of acknowledgement that I have changed how I am, and I have improved. It’s hard work just relying on your own thoughts all the time.

Frances confided that she felt some of her family would never really accept her change and she is resigned to the idea that they may never give her this validation:

I was at a wedding some time ago and my husband overheard one of my cousins say, “I will keep the bottle under the table out of her way, to avoid temptation”. You see, my cousin couldn’t move on, even after four years had passed, she still thought I might go for another drink given the opportunity. I have resigned myself to the idea that some people won’t accept the change in me and probably won’t even in twenty years.

Acceptance and validation of identity change

Where participants reported validation and acceptance of their reformed self, they valued this and indicated it seemed significant in helping them maintain their changes. Frances reported how, unlike some of her family, her daughter and niece accepted the change in her and, through their own behavior, validated her pre alcohol- dependent self. Significantly, she feels this experience has made her determined to remain sober:

But others are great and accept what has happened and most importantly accept that I have changed…my daughter and my niece have a much more trusting relationship with me…they accept that I no longer drink…they don’t go on about my past drinking all the time and they treat me like they used to do before I drunk so heavily and now I see my grandchildren again…The biggest piece of encouragement I got was when my daughter started bringing the kids round again…she also came to a few meetings so that she could understand what it was all about…I felt like a whole person again and it spurred me on to remain sober.

I have had the benefit of my family around me ever since, supporting me, taking me to meetings and the doctors and giving me encouragement all the time. They have whole-heartedly accepted what I am - an alcoholic who is reformed, if you like, in so far as I have completely stopped drinking and turned my life around from a bloke given months to live to this new person now getting jobs and that.

For Kath, this validation came from her new friends:

I now have mates who are not really fully aware of how bad I was in the past and just see me and judge me on how I have been over the past few years. They seem to see me as having a completely different image or identity to that drunk. Some of them think I am right placid and easy going, which I am really I suppose. When I am with them, I am much happier because they treat me as a good person and not as a drunk. It keeps me going and makes me keep myself good.

Resistance from significant others

For some participants, their significant others seemed reluctant to validate their new selves and instead continued to behave toward them as if they had not changed; some even reported being encouraged to return to their old drinking selves, sometimes making their recovery more difficult. Tracy confided:

The change to this sober person was difficult for me. People were used to manipulating me - they found it difficult to deal with me in the same manner when, all of a sudden, I had changed and could assert myself and say “no, I don’t want to do this and that”, you know what I mean? … I was finding my real self and my own voice… they had got used to the old, drunk me where they could tell me what to do and what to drink if they wanted to and I would be like a lamb to the slaughter. You know, very submissive, as long as you put a drink in front of me, I was happy. When I changed and didn’t drink, I became a bit more assertive and voiced my opinions in an intelligent manner, they just weren’t used to it, and I think it threw them a bit.

Similarly, Mick felt that some of his work colleagues created difficulties for him:

Well, I was hindered at times because when I went out from work, I was the one who people told me they were banking on to give them a good time. They relied on me to be the life and soul of the party… some people were quite disappointed when they met me on a night out and I wasn’t what they expected any more…I was a reasonable sensible bloke, not the pissed-up joker. They would say “Why not just have a couple of drinks like old times? It’s Christmas, it doesn’t matter for once”.

Frances reported that while some of her relatives were supportive and accepted her new self, others actively invalidated it:

Some of them do what I have said, ye know, look like they feel sorry for me and probably hide the drink and let everybody know that is what they’re doing, but pretend they are still my most caring relative… but, are probably just wanting me to make another fool of myself, so that they can tittle-tattle about me.

Discussion

People with substance use disorders (SUDs) often have fewer social network supports (Mowbray et al. Citation2014; Pettersen et al. Citation2019), yet evidence suggests that receiving social support from significant others can help to reinforce changes to addictive behavior and to maintain such change. The findings presented here support this, illustrating how relationships with significant others are perceived by participants as important to maintaining sobriety. But importantly, the findings suggest that our understanding of social support should be extended beyond the provision of practical help, care and general encouragement. White (Citation2010) argues that recovery from an AUD means much more than merely stopping drinking in an otherwise unchanged life and requires major changes in the person’s character, identity and relationships with others. We, therefore, propose that our understanding of ‘social support’ should be extended to include the validation that significant others can provide. Such validation may be key to establishing the reformed social identities that, according to the Social Identity Model, are important to recovery from SUDs. As such, both validation and non-stigmatised social identities may be intimately connected.

Our findings support existing research indicating the importance of a positive social identity in sustaining recovery (Longabaugh et al. Citation2010; Best et al. Citation2014; et al. 2015; Best et al. Citation2018). Our participants reported instances where their new sober identities had either been validated or invalidated by significant others or reported an absence of validation. Instances of validation included participants’ perceptions that others accepted and believed in their new, sober identity, ‘took them seriously’, trusted them and changed their behavior accordingly. Instances of invalidation included a lack of acknowledgement of the person’s change, continuing to invoke and refer to the participant’s past alcohol-dependent identity, and even actively encouraging them to drink. Hill and Leeming (Citation2014), in their research on recovery from alcohol dependency, report that recoverees’ new identities may be unstable, and vulnerable to others’ perceptions. They conclude that ‘the narratives people are supported to develop about their experiences and selves are an important part of the recovery process’ (p768).

Within a PCP framework, our social identities, and our attempts to change these, must be understood as a feature of role relationships. So validation and invalidation must also be understood in these conceptual terms. PCP is a social psychology, in that it regards a person’s conduct as always a function of the reciprocal roles they take up within their relationships with others. These roles should not be understood in the same way as structural roles (such as ‘teacher’ or ‘police officer’) but rather imply the behaviors, thoughts and feelings anticipated of someone who becomes, say, ‘the quiet one’ in a family or ‘the organiser’ in a marriage.

Furthermore, Kelly (Citation1955, p. 178) says: ‘One’s construction of his [sic] role must necessarily be validated in terms of the expectancies of the persons with respect to whom he construes his role.’ Procter (Citation1985) later drew attention to ‘how people take up positions with and against each other in group or family situations’ and went on to develop what he termed ‘Relational Construct Psychology’ (Procter, Citation2016, p. 169). So although our participants’ significant others often may have approved the changes the person was striving to make, participants perceived they nevertheless sometimes invalidated their reformed selves, perhaps because those others would have to adopt a different role in their relationships with them. Reluctance to validate the person’s new sense of self may therefore sometimes come from a psychological investment in old role relationships. Conversely, it could also be argued that this psychological investment provides a service to the recoveree in testing their conviction and faith in their new identity. Further research is warranted to unpack these relational dynamics, but this links to our final point; that validation arguably contributes to the person’s ‘intrinsic motivation’ to change.

Intrinsic motivation comes from the person’s own desires and goals rather than those of other people and has been shown to be a factor in recovery from SUDs (for example, Zeldman et al. Citation2004). Theories that have been influential in intervention in recovery from AUDs, such as Self Determination Theory and Motivational Interviewing (Deci and Ryan, Citation1985) argue change requires the person to have an internal sense of control and autonomy. To achieve this, significant others need to respect the individual’s choices, provide a safe environment for the practice of new behavior and offer acceptance, warmth, understanding and unconditional positive regard (Cleverley et al. Citation2018; Chan et al. Citation2019). This is consistent with Webb et al.’s (Citation2022) finding that, as their recovery progressed, recoverees internalized their new social identities, becoming more agentic and self-determining.

Reflecting on the research process

The first author’s decision to be open with participants about his own history of problems with alcohol was seen as an appropriate ethical and methodological choice, establishing an arguably more equal relationship with them and helping to avoid the potentially stigmatizing effects of disclosing details about their alcohol dependency. The rigorous coding procedure helped to ensure that the first author remained open to issues and experiences that were not part of his own taken-for-granted assumptions. Indeed, the emergence of validation as an issue for participants had not been anticipated. The research experience was also transformative for the first author, helping him to view his own experiences in a wider context and to gain a more nuanced picture of AUDs and their effects.

We believe that the research satisfies the four criteria for trustworthiness in qualitative research described by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985). Their first criterion, credibility, requires that the methodology is justified and that the findings are coherent and believable; the qualitative methodology adopted here is entirely consistent with the research aim and with the theoretical approach of PCP, and therefore appropriate. Credibility was also achieved through the substantial number and depth of the interviews. The second criterion, dependability, refers to the trustworthiness of the research process, including consistency in the data collection and researcher involvement. In the case of this research, all data were collected by the lead author and the data collection process was the same for all participants, whilst being tailored to individual needs, and in the same setting. Dependability is also ensured by providing a detailed account of the methods used for data collection and analysis. The third criterion, confirmability, requires that steps have been taken to ensure that the findings are not the outcome of researcher bias, including checking and re-checking the data in the analysis. The findings are confirmable since they are the outcome of a thorough and exhaustive iterative analysis of the data, many iterations of the template, in which the relationship between themes and data was under regular scrutiny; discussion of the ongoing analysis between the three authors helped to ensure that the analysis was sound and grounded in participants’ realities. The final criterion refers to the transferability of the findings. Qualitative research does not (and cannot) make claims about replicability. But the findings are considered transferable since it seems likely that validation/invalidation is relevant to understanding the experiences of people recovering from a range of SUDs in contexts other than self-help groups.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The study included only those who considered themselves to have successfully maintained sobriety. It therefore cannot tell us about experiences of validation in those who have not achieved or maintained change. Future research might fruitfully explore the validation experiences of such people to help establish the importance of this in the recovery process. Additionally, although participants’ significant others were perceived to demonstrate validation or invalidation in various ways, the research does not tell us what those significant others actually did, or how they themselves perceived their own behavior. Exploring validation from the perspective of significant others as well as recoverees may help identify interpersonal issues relevant to recovery.

A further limitation of the study is that all participants had maintained long-term sobriety despite some reports of receiving invalidation from significant others. This could shed doubt on the importance of validation, but equally, it may be that it is not important for a person to receive validation from all members of their social network, or that invalidation may operate to reinforce a person’s desire to change–to ‘prove someone wrong’. These unexplored nuances suggest the need for further research on this concept, and our study may serve as preliminary research in this respect. In addition, as many of the participants had reported an extensive period of sobriety, it may be that their retrospective accounts were influenced by this; reflecting back over a long period of time might have produced subtly different accounts from those produced by reflecting over a shorter time period. Considered through a constructivist lens, this does not mean that the findings are doubtful, but that we should expect different versions of accounts of events depending on time, memory and intervening experiences.

The first author disclosed to participants that he was recovering from an AUD; it was anticipated that this would build trust and encourage openness, and the interviews appeared to demonstrate that this was the case. However, it is possible that some participants may have felt that their own efforts to achieve sobriety were poor by comparison with his, and sought to address this social desirability issue by reporting greater success than they actually experienced. The stigma attached to AUDs may therefore affect research in a variety of ways, and it may be difficult or impossible to assess the impact of these effects on the research findings.

Finally, it is anticipated and acknowledged that people from ethnic minorities, such as the southeast Asian communities living in the research recruitment areas, may have very different experiences of achieving and maintaining sobriety from those reported here. Minority ethnic groups are under-represented in seeking treatment and advice for drinking problems in the UK, and, in particular, drinking problems among women from South Asian ethnic groups may be concealed (Hurcombe et al. Citation2010). Such groups, therefore, constitute a ‘hard to reach’ population for researchers. In addition, as this was a PhD study, with limited resources, it was not realistically possible to extend the sample to achieve greater diversity.

Recommendations for practice

The findings indicate the value that people recovering from alcohol dependency place on reconstruing themselves to develop an identity consistent with the changes they desire. Therefore, interventions might focus on providing opportunities where such re-construal may be facilitated.

Professionals and self-help groups could assist in enabling significant others to recognize the value of validation in addition to more general social support. This would shift responsibility away from the individual toward recognizing the co-creative influence of their wider relationship network. For example in self-help groups, recoverees and their significant others might ‘practice’ new identities and the behavioral validation of these through the use of imaginative role-play techniques akin to Fixed Role Therapy (Kelly, Citation1955; Bannister and Fransella Citation1993).

Conclusion

PCP argues that our sense of self is intimately bound up with how others construe (and therefore behave toward) us and that we need validation from others in order to create and maintain our identity and sense of self (Button Citation1996). When we behave toward and interact with others from the platform of the new self we are trying to forge, if others will not recognize this self we cannot ‘live’ it. Our findings demonstrate the importance that people recovering from AUDs placed upon receiving (or not receiving) this validation from family, friends and work colleagues, not only in legitimating and giving credibility to their new self, but also in deepening their resolve to remain sober. It seems likely that the role and importance of validation as a form of social support in recovery may be similar across a range of addictions, and our findings are therefore likely to have wider applicability and relevance beyond alcohol use disorders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bannister D, Fransella F. 1993. Inquiring man: the psychology of personal constructs. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Beattie MC. 2001. Meta-analysis of social relationships and post treatment drinking outcomes: comparison of relationship structure, function and quality. J Stud Alcohol. 62(4):518–527.

- Best D, Bliuc A-M, Iqbal M, Upton K, Hodgkins S. 2018. Mapping social identity change in online networks of addiction recovery. Addiction Res Theory. 26(3):163–173.

- Best D, Lubman D, Savic M, Wilson A, Dingle G, Haslam A, Haslam C, Jetten J. 2014. Social and transitional identity: exploring social networks and their significance in a therapeutic community setting. Therapeutic Comm. 35(1):10–20.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2023. Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychology Rev. 1–24. Epub ahead of print. DOI:10.1080/17437199.2022.2161594

- Brooks AT, Lopez MM, Ranucci A, Krumlauf M, Wallen GR. 2017. A qualitative exploration of social support during treatment for severe alcohol use disorder and recovery. Addict Behav Rep. 6:76–82.

- Brooks J, McCluskey S, Turley E, King N. 2015. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual Res Psychol. 12(2):202–222.

- Button E. 1996. Validation and invalidation. In: J.W. Scheer, A. Catinaeditors. Empirical Constructivism in Europe: the Personal Construct Approach. Giessen, Germany: Psychosozial-Verlag; p. 142–148

- Chan GH, Wing Lo T, Tam CHL, Lee GKW. 2019. Intrinsic motivation and psychological connectedness to drug abuse and rehabilitation: the perspective of self-determination. IJERPH. 16(11):1934.

- Cleverley K, Grenville M, Henderson J. 2018. Youths perceived parental influence on substance use changes and motivation to seek treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 45(4):640–650.

- Deci E, Ryan R. 1985. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

- Dingle GA, Cruwys T, Frings D. 2015. Social identities as pathways into and out of addiction. Front Psychol. 6:1795.

- Ellis B, Bernichon T, Yu P, Roberts T, Herrell JM. 2004. Effect of social support on substance abuse relapse in a residential treatment setting for women. Eval Program Plann. 27(2):213–221.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS, Denzin NK. 1994. In N.K. Denzin, Y.S. Lincoln, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. New York: Sage. p 105–17.

- Hill JV, Leeming D. 2014. Reconstructing ‘the alcoholic’: recovering from alcohol addiction and the stigma this entails. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 12(6):759–771.

- Hurcombe R, Bayley M, Goodman A. 2010. Ethnicity and alcohol: a review of the UK literature. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/ethnicity-alcohol-literature-review-summary.pdf.

- Kelly GA. 1955. The psychology of personal constructs. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- King N. 2012. Doing template analysis. In G. Symon, C. Casseleditors. Qualitative Organisational Research: core methods and current challenges. London: Sage, p. 426–450.

- Klingemann H. 1992. Coping and maintenance strategies of spontaneous remitters from problem use of alcohol and heroin in Switzerland. Int J Addict. 27(12):1359–1388.

- Laudet AB. 2007. What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. J Subst Abuse Treat. 33(3):243–256.

- Laudet AB, Savage R, Mahmood D. 2002. Pathways to long-term recovery: a preliminary investigation. J Psychoactive Drugs. 34(3):305–311.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. 1985. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, Ca: Sage.

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zywiak WH, O'Malley SS. 2010. Network support as a prognostic indicator of drinking outcomes: the COMBINE study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 71(6):837–846.

- Mericle AA. 2014. The role of social networks in recovery from alcohol and drug abuse. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40(3):179–180.

- Moos RH, Moos BS. 2007. Protective resources and long-term recovery from alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 86(1):46–54.

- Mowbray O, Quinn A, Cranford JA. 2014. Social networks and alcohol use disorders: findings from a nationally representative sample. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40(3):181–186.

- Pettersen H, Landheim A, Skeie I, Biong S, Brodahl M, Oute J, Davidson L. 2019. How social relationships influence substance use disorder recovery: a collaborative narrative study. Subst Abuse. 13:117822181983337.

- Procter H. 1985. A construct approach to family therapy and systems intervention. In E. Button editor. Personal Construct Theory and Mental Health. Beckenham: Croom Helm. p. 327–350.

- Procter H. 2016. Relational construct psychology. In D.A. Winter and N. Reededitors. The Wiley Handbook of Personal Construct Psychology. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 167–177.

- Thomas D. 2017. Feedback from research participants: are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qual Res Psychol. 14(1):23–41.

- Tracey K, Wallace S. 2016. Benefits of peer support groups in the treatment of addiction. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 7:143–154. DOI: 10.2147/SAR.S81535

- Webb L, Clayson A, Duda-Mikulin E, Cox N. 2022. ‘I’m getting the balls to say no: trajectories in long-term recovery from problem substance use. J Health Psychol. 27(1):69–80.

- Westwell G. 2021. The role of personal meaning for alcoholics in achieving and successfully maintaining sobriety. Unpublished PhD thesis. UK: University of Huddersfield.

- White WL. 2010. Commentary on Kelly et al. (2010): alcoholics anonymous, alcoholism recovery, global health, and quality of life. Addiction. 105(4):637–638.

- Winter DA, Viney LL. 2005. Personal construct psychotherapy: advances in theory, practice, and research. London: Whurr.

- Yeh MY, Che HL, Wu SM. 2009. An ongoing process: a qualitative study of how the alcohol-dependent free themselves of addiction throught progresive abstinence. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1):76.

- Zeldman A, Ryan R, Fiscella K. 2004. Motivation, autonomy support, and entity beliefs: their role in methadone maintenance treatment. J Soc Clin Psychol. 23(5):675–696.

- Zywiak WH, Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW. 2002. Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment social network characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. J Stud Alcohol. 63(1):114–121.