Abstract

Background

Gambling marketing is ubiquitous in UK football and, despite gambling industry self-regulation such as the whistle-to-whistle ban, remains prominent in live TV coverage. Major international tournaments do not usually feature gambling pitch-side advertising and shirt sponsorship, increasing the importance of TV adverts during these high-profile competitions. The present study examined the prevalence and features of gambling adverts shown during the commercial broadcaster ITV’s live coverage of games in the 2022 Qatar World Cup.

Method

Each match shown live on ITV was recorded. For each gambling advert, the timing of the advert (pre-/during-/post-match), the advert category (financial inducements/live odds/safer gambling/brand awareness) and safer gambling messaging were recorded.

Results

Over the 30 matches analyzed, there were 156 adverts directly for gambling brands or products (M = 5.2, range 3 – 8), featuring adverts from eight different operators. The majority of adverts were shown pre-match (80.8%). Financial inducements were most commonly advertised (42.3%), followed by brand awareness adverts (26.9%). The safer gambling message ‘take time to think’ was shown in 70.5% of adverts. Adverts for lottery products did not feature any safer gambling messages.

Conclusions

Multiple gambling adverts were shown during each match of the 2022 Qatar World Cup, especially so pre-match. Pre-match adverts predominantly encourage viewers to gamble promptly, through financial inducements and boosted live odds. Any potential further legislation could therefore consider either further restrictions based on the entire broadcast, or by enforcing the use of specific safer gambling messages.

Introduction

Gambling is a common activity worldwide, and particularly in the UK; recent figures indicate that in the year to September 2022, past four-week gambling participation was 44% (Gambling Commission Citation2022). The UK legislative environment allows the promotion and provision of many types of gambling, however one of the increasingly more common forms is sports betting, particularly on football (McGee Citation2020). Excluding lottery products, sports gambling is the most commonly engaged in form of gambling, both online and in-person (Gambling Commission Citation2022). While gambling can be an enjoyable leisure activity, it can also be harmful for many gamblers (Browne et al. Citation2016; Muggleton et al. Citation2021).

Despite some international jurisdictions such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain making recent moves to restrict gambling advertising, many types of gambling marketing appear currently around football in the UK (Newall et al. Citation2019; Sharman Citation2022; Torrance et al. Citation2021), a trend which has been called the ‘gamblification of sport’ (McGee Citation2020). Gambling marketing can appear in football via shirt sponsorship (Bunn et al. Citation2019), matchday programmes (Sharman et al. Citation2020; Citation2023), pitch side advertising boards surrounding the playing area (Purves et al. Citation2020); direct marketing (Syvertsen et al. Citation2022); through the social media accounts of operators (Killick and Griffiths Citation2020; Rossi and Nairn Citation2022), and affiliates (Houghton et al. Citation2019); smartphone apps (Jones et al. Citation2020); and highlight TV programmes such as Match of the Day (Cassidy and Ovenden Citation2017). Most pertinent to the current study, since the implementation of the 2005 Gambling Act, gambling is also promoted through TV adverts during live matches (Newall et al. Citation2019).

International matches in major tournaments such as the European Championships and the World Cup attract substantial viewing figures; figures from FIFA indicate the over 3.5 billion people globally watched matches of the 2018 World Cup in Russia, with 1.12 billion people globally watching the final. For the World Cup in Qatar, commercial broadcaster ITV showed the three most watched games; England’s quarter-final defeat to France reached a peak audience of 23 million viewers across TV and streaming platforms, whilst 20.4 million watched England beat Senegal, and 18 million watched England draw with the USA (ITV Citation2022). However, international matches present a different set of gambling marketing exposures to the domestic British leagues. There is no shirt sponsorship in the international game, and minimal use of pitch-side advertising boards for gambling, therefore there is less in-game exposure to gambling marketing. Research on previous World Cups has reported that although there was no gambling marketing on pitch-side advertising boards, gambling (n = 38, 45.2%) was the most frequently advertised unhealthy brand category during commercial breaks (compared to food/beverages (n = 22, 26.2), and alcohol (n = 24, 28.6%) (Ireland et al. Citation2021). However, immediately prior to Qatar 2022, FIFA announced their first official partnership with a gambling partner (Sale Citation2022), and with a cryptocurrency trading platform for pitch-side advertising, which mirrors a trend toward increasing exposure to cryptocurrency brands in the English domestic game (Newall & Xiao, Citation2021; Torrance et al. Citation2023). Therefore, TV adverts are the primary method of brand promotion available on televised international matches; during commercial coverage of the 2018 World Cup one in six TV adverts were for gambling, and this proportion was the highest out of all industries (Duncan et al. Citation2018).

In response to growing political pressure around the prevalence of gambling adverts in UK football, a voluntary measure was introduced by the gambling industry to limit the number of gambling adverts shown during live broadcasts of football matches (Conway Citation2018). Labeled the ‘whistle-to-whistle’ ban, the measure proposed that no gambling adverts should be shown from five minutes prior to kick off and during the match, to five minutes after the final whistle, including any match that starts before the 9 pm watershed. Despite being a ‘ban’, this measure is not without limitations. The first major international tournament to feature nations from the United Kingdom following implementation of the whistle-to-whistle ban was the 2020 European Championships (Euro 2020), held in 2021 due to COVID-19. Despite the whistle-to-whistle ban, 113 gambling adverts were shown during coverage of live matches during the tournament, at an average of 4.5 adverts per match (Newall et al. Citation2022a).

The timing of the adverts within the broadcast was also examined in the Euro 2020 study; a significant proportion of adverts (93; 82.3%) were observed prior to kickoff, with a much smaller number (18; 15.9%) happening after the final whistle. Gambling adverts have been shown to increase gambling behavior (Killick and Griffiths Citation2021), with greater advertising exposure linked with a greater risk of harm (Bouguettaya et al. Citation2020; McGrane et al. Citation2023). If these findings on advert timing can be replicated, then this would create an evidence-based recommendation for people watching football who want to avoid seeing gambling adverts to avoid the match build-up prior to kickoff.

Previous research has also indicated that gambling adverts shown during international tournaments can be assigned to distinct categories (Newall et al. Citation2019; Killick and Griffiths Citation2021). The recent study on Euro 2020 adverts revealed that some categories were shown more often than others. ‘Financial inducements’, which can include inducements such as boosted odds or free bets (Browne et al. Citation2019; Hing et al. Citation2019), were shown most often (56.6% of gambling adverts) (Newall et al. Citation2022a). ‘Brand awareness’ adverts do not provide any key offer to gamblers, but remind gamblers about a given operator’s brand and often attempt to create positive associations based on viewer (Lopez-Gonzalez et al. Citation2018), and accounted for 19.5% of gambling adverts in Euro 2020 coverage (Newall et al. Citation2022a). ‘Live odds’ adverts show odds on bets on an upcoming event(s) within the match, with varying degrees of complexity ranging from a single event such as first goal scorer, to sequences of multiple events combining the first goal scorer, correct score, and total goals etc. (Newall et al. Citation2019; Rockloff et al. Citation2019; Newall et al. Citation2020). Live odds adverts accounted for 18.6% of gambling adverts during Euro 2020 (Newall et al. Citation2022a). ‘Safer gambling’ adverts principally remind viewers about the importance of safer gambling and the presence of safer gambling tools. Safer gambling adverts are a further example of the gambling industry’s current self-regulatory approach and were a new category seen in 2020 compared to 2018, but were rarely shown, accounting for 5.3% of gambling adverts (Newall et al. Citation2022a).

The Euro 2020 study also showed that all gambling adverts had at least one safer gambling message shown at the end or for its duration. But most adverts (56.6%) showed the industry-led ‘when the fun stops, stop’ message, which has been shown to have no positive impact on contemporaneous gambling behaviors (Newall et al. Citation2022a). In late 2021 this message was replaced by the new industry-led message, ‘take time to think’, a message which has improved levels of face validity, but which also shows little beneficial effect on contemporaneous safer gambling behaviors (Newall et al. Citation2023). By comparison, Australia has recently moved toward mandating operators to use a set of independently-designed safer gambling messages, such as ‘chances are you’re about to lose’, and ‘you win some. You lose more’ (Butler Citation2022).

Aims

TV advertising is therefore particularly important during live coverage of international tournament matches. The frequency of advertising overall and distinct categories of adverts show some level of change over time, both in response to policy changes such as the whistle-to-whistle ban, and also show some level of natural change, with a small number of safer gambling adverts being first observed during Euro 2020 (Newall et al. Citation2022a). The continuing monitoring of gambling advertising content can therefore assist other stakeholders, such as football viewers who want evidence-based recommendations to minimize gambling advert exposure, or policymakers who might want to assess voluntary measures such as the whistle-to-whistle ban, and safer gambling messages and adverts. The current study therefore aimed to:

Record the frequency of gambling advertising shown on UK commercial television during the 2022 men’s Football World Cup in Qatar.

Record the segment of the coverage in which the advert appeared.

Record the proportion of advertising focusing on specific marketing categories including financial inducements, odds, safer gambling features, and those focused on raising brand awareness.

Record the type and content of any safer gambling messaging.

Method

Data and a wider selection of advert screenshots are available from: https://osf.io/bpwmc/.

The FIFA Men’s World Cup 2022, hosted in Qatar, consisted of 64 matches, including 48 in the group stage, eight matches in the Round of 16, four in the quarterfinals, two in the semifinals, the third-place playoff, and the final. All matches were shown on UK terrestrial television; 32 matches were shown on commercial broadcaster ITV, and were recorded via Sky TV. The remaining matches were only shown on the BBC, a noncommercial broadcaster that does not show adverts. Due to a technical failing, two matches on ITV (Portugal v Uruguay and Spain v Costa Rica) were not recorded, therefore adverts from 30 matches were included for analysisFootnote1. The recordings of the live ITV broadcasts were rewatched for coding purposes. Following a previous study (Newall et al. Citation2022a), adverts were coded from the first advert break following the start of the match programme, until the last advertising break shown before the match programme finished. This was an observational, cross-sectional study.

Data extraction and variables

The adverts in one match were jointly coded by TP and SS. A further five matches were then independently coded by TP and SS, and then extracted data compared to ensure consistent agreement. Percentage agreement was used to calculate inter-rater reliability. Any coding disagreements between the two coders was discussed, and agreement was reached via consensus, and if needed be, via the help of another research team member. All coded variables reached a satisfactory level of inter-rater reliability (>90%), exceeding the 70% level of agreement that is considered acceptable (Stemler and Tsai Citation2008), and reaching a level of agreement considered excellent (Cicchetti Citation1994). Subsequently, all remaining matches were coded by TP. The variables that were extracted for each match are summarized in .

Table 1. Variables extracted for each advert.

Analysis plan

Independent samples t tests were used to compare advert frequency between specific groups (home nation/Other; Group stage v knockout); Cohen’s d is reported as a measure of effect size. Chi squared analysis was used to examine differences in category of advert, and programme segment (before v other). Chi squared models were also used to compare advert prevalence, programme segment, and advert types, between matches shown on ITV during the Qatar 2022 World Cup, and similar data collected during the Euro 2020 tournament (data already collected for a previous study). Cramer’s V is reported as a measure of effect size. 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) are reported.

Results

Advert frequency and timing

Across the 30 matches shown on ITV during the 2022 World Cup in Qatar that were analyzed, 176 gambling related adverts were shown, including 20 adverts (11.4%) for Gamble Aware (exclusively promoting safer gambling). Subsequent analysis is run only on the 156 adverts that were from gambling companies, or promoting specific gambling products (e.g. lotteries).

The 30 matches analyzed averaged 5.2 adverts per match (s.d. 1.2). The lowest number of adverts featured in single match coverage was 3 (Cameroon vs Brazil), and the highest was 8 (Portugal vs Ghana and England vs USA). Eight different operators advertised on ITV: Paddy Power (n = 30), Skybet (n = 30) and Bet365 (n = 29) were the most common advertisers.

There were significantly more gambling adverts in matches featuring home nations (England and Wales), (M = 6.5, s.d. = 1.0), than those not featuring a home nation (M = 5.0, s.d. = 1.1), (t (28) = 2.66, p = .013, d = 1.24, 95% CI [0.3, 2.53]), although results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of games featuring either England or Wales (n = 4). There was no difference in the number of adverts shown per match in the group stage (M = 5.1, s.d. = 1.3), or the knockout stage (M = 5.4, s.d = 0.8), (t (28) = .49, p = .63, d = −.20, 95% CI [−1.01, .61).

Of the 156 gambling adverts, 126 were shown pre-match (80.8%); 5 were shown between kick off and the match conclusion (3.2%), and 25 were shown following conclusion of the match (16%). Only adverts for the National Lottery, and the People’s Postcode Lottery were shown in between kick off and match conclusion.

Advert type

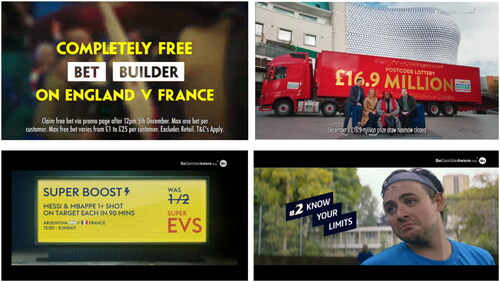

The most common advert type was financial inducements (n = 66, 42.3%), used by five different operators, predominantly offering free bets, free bet builders, or ‘bet bundles’. Of the 66 Financial Inducement adverts, 54 (81.8%) were shown prior to match kick off. Brand awareness and live odds adverts appeared with similar frequency; brand awareness adverts (n = 42, 26.9%) were used by four operators; 28 of 42 (66.7%) of Brand awareness adverts were shown prior to kick off. Direct promotion of Live Odds (n = 39, 25%) was used by 3 operators, and 38 of 39 (97.4%) were shown prior to kick off, advertising odds on the upcoming match. Of the 156 gambling adverts, 9 were operator specific safer gambling adverts (5.8%). Safer gambling adverts were shown by three operators, and included references to the individual operator’s own safer gambling tools. Of the 9 safer gambling adverts, 6 were shown prior to kick off (66.7%). See for advert type examples. Chi squared analysis indicates a significant difference in the segment distribution between advert types (χ2 (6) = 23.23, p <.001, V = .27, 95% CI [<.001, .003]), driven by a higher proportion of live odds and financial inducement adverts being shown prior to kick off (see ).

Figure 1. Examples of financial inducement (© 2021 Paddy Power), brand awareness (© Postcode Lottery), live odds (© SkyBet), and safer gambling (© William Hill) adverts.

Copyright notice. The authors acknowledge that the copyright of all screenshots used in are retained by their respective copyright holders. The authors use these copyrighted materials for the purposes of research, criticism or review under the fair dealing provisions of copyright law in accordance with Sections 29(1) and 30(1) of the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Table 2. Advert type, by programme segment.

Safer gambling messages

Of the 156 gambling adverts, 139 contained a safer gambling message (89.1%); 110 of the 156 gambling adverts contained the ‘take time to think’ message (70.5%) and 29 adverts contained other messages (18.6%). All of the 29 gambling adverts with an ‘other’ safer gambling message were advertising the brand Bet365; 24 of the 29 Bet365 adverts instead had Ray Winstone stating ‘Please gamble responsibly’. 17 adverts had no safer gambling message (10.9%). Of the 139 adverts with a safer gambling message, 133 messages were shown just at the end (95.7%), with just six shown throughout (4.3%).

For the 110 adverts that showed the ‘take time to think’ message, only 28 maintained sole focus on the message (25.5%); 79 adverts (71.8%) displayed, either audibly or visually, a competing brand promotion message (). The only adverts not to feature any safer gambling messaging were for the National Lottery, and the People’s Postcode Lottery. Dedicated safer gambling adverts, from Gamble Aware (n = 20) occurred at a rate of less than one per broadcast match; 19 adverts were in group stage matches, and only one featured in ITV coverage of knockout matches. All Gamble Aware adverts were in the pre-game segment, and all featured the ‘bet regret’ slogan represented by a bad tattoo.

Table 3. Safer gambling messages in adverts.

Discussion

The present study sought to investigate the frequency and content of gambling adverts shown on a commercial broadcaster in the UK, during the recent 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup, in Qatar. Overall, 176 gambling related adverts were shown, including 20 safer gambling specific adverts from Gamble Aware that were not included in any analyses. Coverage included 156 gambling specific adverts across 30 games shown on TV – an average of 5.2 per game –- similar to the 4.5 adverts per broadcast from Euro 2020 (Newall et al. Citation2022a). The most commonly observed advert type in the present study was financial inducements, consistent with previous research (Newall et al. Citation2022a). Safer gambling adverts were the least commonly observed.

This study continued on previous work looking at the frequency and content of gambling advertising shown during televised football subsequent to the whistle-to-whistle ban. It could be argued that the optimum time to advertise financial inducements and live odds is in the run up to kick off, a window not affected by the whistle-to-whistle ban. The content of the adverts in the present study was primarily financial inducements, often related to the imminent game. Live odds for specific events in the coming match also accounted for a significant portion of pre-game adverts. This is noteworthy, as in a move toward greater consumer protection, regulatory guidance around creating a sense of impulsiveness and urgency in gambling states that:

‘In order not to encourage gambling behaviour that is irresponsible, marketing communications should not unduly pressure the audience to gamble, especially when gambling opportunities offered are subject to a significant time limitation.’ (Committee of Advertising Practice Citation2018, p.6).

Financial inducements tied to specific matches and live odds advertising that are only valid until the match starts are inherently time-limited, and would therefore appear to contravene guidance (Newall et al. Citation2019). Adverts that invoke a sense of urgency or include financial offers/inducements are most influential (Nyemcsok et al. Citation2021), and time pressure has been identified as an important characteristic of the situational and structural characteristics of adverts (Hing et al. Citation2018). Exposure to inducements leads to people choosing riskier bets with longer odds (Rockloff et al. Citation2019), can be seen to minimize losses which can lead to extended gambling (Hing et al. Citation2018), whilst free bets are seen as ‘safety nets’ that lead to betting when respondents otherwise had not planned to (Deans et al. Citation2017). Promotions offered through adverts particularly negatively influence gamblers in active treatment (Lopez-Gonzalez et al. Citation2020). However despite the CAP guidance and support for banning advertising strategies to incentivise gambling/invoke a sense of urgency to bet (Regan et al. Citation2022), these types of features and category of advertising are still common pre-kick off.

A notable exception to the whistle-to-whistle ban are lottery products including the National Lottery and the People’s Postcode Lottery; all adverts that appeared during the match (half-time) were lottery based. Previous research has shown that engagement with lottery-based products can result in some level of gambling related risk, with males, younger respondents, and smokers among those more likely to report problematic use of lottery products (Booth et al. Citation2020). An advertising ban that doesn’t cover all gambling and still allows some products to be advertised, will still allow for gambling exposure. Previous research has indicated that marketing prompts such as TV adverts can prompt unplanned spending (Wardle et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, recent reviews report the existence of a causal relationship between advertising exposure and increased gambling activity, with greater advertising exposure linked with a greater risk of harm (Bouguettaya et al. Citation2020; Killick and Griffiths Citation2021; McGrane et al. Citation2023). Any restrictions on gambling marketing as a measure to prevent harm, could arguably therefore include all types of gambling, across all TV coverage of a live match, not just from kick off to the full-time whistle.

Consistent with previous research on gambling marketing (Critchlow et al. Citation2020), in the present study, all gambling advertising that was not lottery based, contained some kind of safer gambling messaging, despite previous research indicating that people don’t believe safer gambling messaging is effective and are supportive of increased regulation of advertising (Torrance et al. Citation2021). Previous research has demonstrated that safer gambling messages are ineffective. ‘Take time to think’ has been subject to an independent test, and shown to have no credible beneficial effect on contemporaneous gambling behaviors (Newall et al. Citation2023). Furthermore, a study examining the efficacy of the previously used message, ‘When the fun stops, stop’, found no evidence of a protective effect (Newall et al. Citation2022b). These findings suggest that safer gambling messages should be developed and implemented independently of the gambling industry, a model which Australia has implemented (Butler Citation2022). Moreover, the delivery of the safer gambling message warrants further discussion. For some adverts, the ‘take time to think’ message appeared at the end of the advert, and was either displayed audibly and visually, or only visually with no audio accompaniment. However for some adverts, across multiple operators, the safer gambling message was only presented visually, and was accompanied by audio stimuli that was delivering the operator’s marketing slogan. For example, whilst the words ‘take time to think’ were on the screen, the Skybet advert was simultaneously telling us ‘that’s betting, better’, Paddy Power were asking ‘where were you in ‘22′, and William Hill were claiming ‘It’s who you play with’. For one operator the ‘take time to think’ message was not included, instead replaced by actor Ray Winstone urging viewers to ‘please gamble responsibly’. This emphasis on personal responsibility is a gambling industry supported narrative that portrays products as harmless to all but an atypical minority and fails to acknowledge upstream determinants of harm, contrary to a successful public health approach (van Schalkwyk et al. Citation2021).

The findings are not without limitations. Although able to quantify the number of adverts shown, the current study does not investigate the impact of advert exposure on viewers gambling; previous research indicates that advertising impacts gambling behavior, specifically in sports betting (Killick and Griffiths Citation2022). The impact of advertising on behavior is a fundamental component of the debate around gambling marketing and advertising (Wardle et al. Citation2022). Furthermore, although the current research endeavored to capture live recordings via a Sky + box, an unforeseen recording clash meant two matches were not recorded and therefore not analyzed. Given the consistent nature of advert timing and content across all analyzed matches, it is not anticipated that the exclusion of these matches has significantly impacted the findings. In future studies, a dedicated account for recording full broadcasts could be utilized to ensure full coverage. Capture of the live broadcast is important to accurate recording of broadcast adverts; although both matches were available on catch-up services such as Box of Broadcasts, the frequency and content of gambling adverts was different. It is therefore recommended that researchers extract data from live recordings rather than rely on catch-up services. Further work should explore variations in gambling adverts based on region (e.g. Scotland vs. England) and time (live versus catch-up). Additionally, the current study was designed to capture exposure to one specific type of marketing, TV adverts so was therefore unable to investigate the relationship with other types of gambling marketing such as direct marketing and social media (Rossi et al. Citation2021); these are more personal, widespread forms of marketing which often benefit from loopholes in advertising legislation making them more difficult to measure (Russell et al. Citation2018; Rawat et al. Citation2020).

The findings in this study highlight how gambling adverts during coverage of major international tournament football are prevalent outside of the current restrictions, ensuring that any viewer watching pre-match build up will be exposed to gambling marketing. Adverts occur most commonly before the match and present the viewer with either financial inducements to gamble, or live odds on the upcoming match. Any legislation designed to minimize exposure to gambling marketing should therefore consider both the timing of the adverts in relation to overall coverage, and the type of advert being shown.

Ethics statement

This research did not require ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

SS: Steve Sharman is funded by a UKRI Future Leader’s Fellowship (FLF). The FLF scheme is funded by UK Research and Innovation, Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Innovate UK, Medical Research Council (MRC), Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC). He has previously received funding from the Society for the Study of Addiction (SSA), and a King’s Prize Fellowship, funded by the Wellcome Trust and the London Law Trust. He has also received honorarium from Taylor Francis Publishing, the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling (AFSG) funded by GREO, the SSA, Health and Social Care Wales, and the RANGES early career network. SS is a member of the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling – an advisory group of the Gambling Commission in Great Britain. SS has no conflicts of interest to declare. TP: Theodore Piper has no interests to declare. EM: Ellen McGrane is funded by a Wellcome Trust doctoral grant [224852/Z/21/Z]. EM has no conflicts of interest to declare. PN: Philip Newall is a member of the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling – an advisory group of the Gambling Commission in Great Britain, and in 2020 was a special advisor to the House of Lords Select Committee Enquiry on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. In the last three years Philip Newall has contributed to research projects funded by the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling, Clean Up Gambling, Gambling Research Australia, NSW Responsible Gambling Fund, and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, received travel and accommodation funding from Alberta Gambling Research Institute, and received open access fee funding from Gambling Research Exchange Ontario.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Matches were available on catch-up service Box of Broadcasts, however brief comparison revealed that advert content on catch-up services was not the same as in live broadcasts. Therefore, only live broadcast recordings were analysed. This issue also meant it was not possible to make an unconfounded comparison between patterns of advertising seen here and those found in a previous study on Euro 2020 (Newall et al. 2022).

References

- Booth L, Thomas S, Moodie R, Peeters A, White V, Pierce H, Anderson AS, Pettigrew S. 2020. Gambling-related harms attributable to lotteries products. Addict Behav. 109:106472. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106472.

- Bouguettaya A, Lynott D, Carter A, Zerhouni O, Meyer S, Ladegaard I, Gardner J, O’Brien KS. 2020. The relationship between gambling advertising and gambling attitudes, intentions and behaviours: a critical and meta-analytic review. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 31:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.02.010.

- Browne M, Hing N, Russell AM, Thomas A, Jenkinson R. 2019. The impact of exposure to wagering advertisements and inducements on intended and actual betting expenditure: an ecological momentary assessment study. J Behav Addict. 8(1):146–156. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.10.

- Browne M, Langham E, Rawat V, Greer N, Li E, Rose J, Best T. 2016. Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: a public health perspective. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

- Bunn C, Ireland R, Minton J, Holman D, Philpott M, Chambers S. 2019. Shirt sponsorship by gambling companies in the English and Scottish Premier Leagues: global reach and public health concerns. Soccer Soc. 20(6):824–835. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2018.1425682.

- Butler J. 2022. ‘You lose more’: Australia to force online gambling ads to include messages on potential harms. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/nov/02/you-lose-more-australia-to-force-online-gambling-ads-to-include-messages-on-potential-harms 20/02/2023.

- Cassidy R, Ovenden N. 2017. Frequency, duration and medium of advertisements for gambling and other risky products in commercial and public service broadcasts of English Premier League football. SocArXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/f6bu8.

- Cicchetti DV. 1994. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 6(4):284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284.

- Committee of Advertising Practice. 2018. Regulatory statement: gambling advertising guidance.

- Conway R. 2018. Gambling firms agree TV advertising ban. BBC Sport. https://www.bbc.com/sport/46453954.

- Critchlow N, Moodie C, Stead M, Morgan A, Newall PWS, Dobbie F. 2020. Visibility of age restriction warnings, harm reduction messages and terms and conditions: a content analysis of paid-for gambling advertising in the United Kingdom. Public Health. 184:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.004.

- Deans EG, Thomas SL, Derevensky J, Daube M. 2017. The influence of marketing on the sports betting attitudes and consumption behaviours of young men: implications for harm reduction and prevention strategies. Harm Reduct J. 14(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0131-8.

- Duncan P, Davies R, Sweney M. 2018. Children ‘bombarded’ with betting adverts during World Cup. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/jul/15/children-bombarded-with-betting-adverts-during-world-cup.

- Gambling Commission. 2022. Statistics on participation and problem gambling for the year to Sept 2022. [accessed 2023 August 6]. https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/statistics-and-research/publication/statistics-on-participation-and-problem-gambling-for-the-year-to-sept-2022.

- Hing N, Russell A, Rockloff M, Browne M, Langham E, Li E, … Rawat V. 2018. Effects of wagering marketing on vulnerable adults. North Melbourne (VIC): Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

- Hing N, Russell AM, Thomas A, Jenkinson R. 2019. Wagering advertisements and inducements: exposure and perceived influence on betting behaviour. J Gambl Stud. 35(3):793–811. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-09823-y.

- Houghton S, McNeil A, Hogg M, Moss M. 2019. Comparing the Twitter posting of British gambling operators and gambling affiliates: A summative content analysis. International Gambling Studies. 19(2):312–326. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2018.1561923.

- Ireland R, Muc M, Bunn C, Boyland E. 2021. Marketing of unhealthy brands during the 2018 Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup UK broadcasts–a frequency analysis. J Strat Market. 29:1–16. doi: 10.1080/0965254X.2021.1967427.

- ITV. 2022. ITV's World Cup coverage sees record streaming figures. ITV Football.

- Jones C, Pinder R, Robinson G. 2020. Gambling sponsorship and advertising in British football: A critical account. Sport Ethics Philos. 14(2):163–175. doi: 10.1080/17511321.2019.1582558.

- Killick E, Griffiths M. 2020. A content analysis of gambling operators’ Twitter accounts at the start of the English Premier League football season. J Gambl Stud. 36(1):319–341. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09879-4.

- Killick E, Griffiths MD; Department of Psychology, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK. 2021. Impact of sports betting advertising on gambling behavior: A systematic review. Addicta. 8(3):201–214. doi: 10.5152/ADDICTA.2022.21080.

- Lopez-Gonzalez H, Griffiths MD, Jimenez-Murcia S, Estévez A. 2020. The perceived influence of sports betting marketing techniques on disordered gamblers in treatment. Eur Sport Manag Quarter. 20(4):421–439. doi: 10.1080/16184742.2019.1620304.

- Lopez-Gonzalez H, Guerrero-Solé F, Griffiths MD. 2018. A content analysis of how ‘normal’ sports betting behaviour is represented in gambling advertising. Addict Res Theory. 26(3):238–247. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1353082.

- McGee D. 2020. On the normalisation of online sports gambling among young adult men in the UK: a public health perspective. Public Health. 184:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.018.

- McGrane E, Wardle H, Clowes M, Blank L, Pryce R, Field M, Sharpe C, Goyder E. 2023. What is the evidence that advertising policies could have an impact on gambling-related harms? A systematic umbrella review of the literature. Public Health. 215:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.11.019.

- Muggleton N, Parpart P, Newall P, Leake D, Gathergood J, Stewart N. 2021. The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat Hum Behav. 5(3):319–326. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w.

- Newall PW, Xiao L Y. 2021. Gambling marketing bans in professional sports neglect the risks posed by financial trading apps and cryptocurrencies. Gaming Law Rev. 25(9): 376–378.

- Newall PWS, Ferreira CA, Sharman S. 2022a. The frequency and content of televised UK gambling advertising during the men’s 2020 Euro soccer tournament. Exp Results. 3:e28. doi: 10.1017/exp.2022.26.

- Newall PWS, Hayes T, Singmann H, Weiss-Cohen L, Ludvig EA, Walasek L. 2023. Evaluation of the “take time to think” safer gambling message: a randomised, online experimental study. Behav Public Policy. 1–18. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2023.2.

- Newall PWS, Moodie C, Reith G, Stead M, Critchlow N, Morgan A, Dobbie F. 2019. Gambling marketing from 2014 to 2018: A literature review. Curr Addict Rep. 6(2):49–56. doi: 10.1007/s40429-019-00239-1.

- Newall PWS, Thobhani A, Walasek L, Meyer C. 2019. Live-odds gambling advertising and consumer protection. PLoS One. 14(6):e0216876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216876.

- Newall PWS, Walasek L, Vázquez Kiesel R, Ludvig EA, Meyer C. 2020. Request-a-bet sports betting products indicate patterns of bettor preference and bookmaker profits. J Behav Addict. 10(3):381–387. doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00054.

- Newall PWS, Weiss-Cohen L, Singmann H, Walasek L, Ludvig EA. 2022b. Impact of the “when the fun stops, stop” gambling message on online gambling behaviour: a randomised, online experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 7(5):e437–e446. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00279-6.

- Nyemcsok C, Thomas SL, Pitt H, Pettigrew S, Cassidy R, Daube M. 2021. Young people’s reflections on the factors contributing to the normalisation of gambling in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 45(2):165–170. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13063.

- Purves RI, Critchlow N, Morgan A, Stead M, Dobbie F. 2020. Examining the frequency and nature of gambling marketing in televised broadcasts of professional sporting events in the United Kingdom. Public Health. 184:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.02.012.

- Rawat V, Hing N, Russell AM. 2020. What’s the message? A content analysis of emails and texts received from wagering operators during sports and racing events. J Gambl Stud. 36(4):1107–1121. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09896-3.

- Regan M, Smolar M, Burton R, Clarke Z, Sharpe C, Henn C, Marsden J. 2022. Policies and interventions to reduce harmful gambling: an international Delphi consensus and implementation rating study. Lancet Public Health. 7(8):e705–e717. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00137-2.

- Rockloff MJ, Browne M, Russell AM, Hing N, Greer N. 2019. Sports betting incentives encourage gamblers to select the long odds: An experimental investigation using monetary rewards. J Behav Addict. 8(2):268–276. doi: 10.1556/2006.8.2019.30.

- Rossi R, Nairn A. 2022. New developments in gambling marketing: the rise of social media ads and its effect on youth. Curr Addict Rep. 9(4):385–391. doi: 10.1007/s40429-022-00457-0.

- Rossi R, Nairn A, Smith J, Inskip C. 2021. “Get a £10 free bet every week!”—Gambling advertising on Twitter: volume, content, followers, engagement and regulatory compliance. J Public Policy Market. 40(4):487–504. doi: 10.1177/0743915621999674.

- Russell AMT, Hing N, Browne M, Rawat V. 2018. Are direct messages (texts and emails) from wagering operators associated with betting intention and behavior? An ecological momentary assessment study. J Behav Addict. 7(4):1079–1090. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.99.

- Sale J. 2022. Betano becomes FIFA’s debut World Cup betting partner in regional deal. Betano becomes first betting partner of World Cup (sbcnews.co.uk) [accessed 2023 Feb 16].

- Sharman S, Ferreira CA, Newall PWS. 2020. Exposure to gambling and alcohol marketing in soccer matchday programmes. J Gambl Stud. 36(3):979–988. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09912-6.

- Sharman S. 2022. Gambling in football: how much is too much? Manag Sport Leis. 27(1-2):85-92. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1811135.

- Sharman S, Ferreira C, Newall PWS. 2023. Gambling advertising and incidental marketing exposure in soccer matchday programmes: a longitudinal study. CGS. 4(1):27–37. doi: 10.29173/cgs116.

- Stemler SE, Tsai J. 2008. Best practices in estimating interrater reliability: three common approaches. In J. Osborne, editor. Best practices in quantitative methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; p. 29–49.

- Syvertsen A, Erevik EK, Hanss D, Mentzoni RA, Pallesen S. 2022. Relationships between exposure to different gambling advertising types, advertising impact and problem gambling. J Gambl Stud. 38(2):465–482. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10038-x.

- Torrance J, John B, Greville J, O'Hanrahan M, Davies N, Roderique-Davies G. 2021. Emergent gambling advertising; a rapid review of marketing content, delivery and structural features. BMC Public Health. 21(1):718. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10805-w.

- Torrance J, Roderique-Davies G, Thomas SL, Davies N, John B. 2021. ‘It’s basically everywhere’: young adults’ perceptions of gambling advertising in the UK. Health Promot Int. 36(4):976–988. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa126.

- Torrance J, Heath C, Andrade M, Newall P. 2023. Gambling, cryptocurrency, and financial trading app marketing in English Premier League football: a frequency analysis of in-game logos. https://osf.io/uv974.

- van Schalkwyk MC, Maani N, McKee M, Thomas S, Knai C, Petticrew M. 2021. “When the fun stops, stop”: an analysis of the provenance, framing and evidence of a ‘responsible gambling’ campaign. PLoS One. 16(8):e0255145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255145.

- Wardle H, Critchlow N, Brown A, Donnachie C, Kolesnikov A, Hunt K. 2022. The association between gambling marketing and unplanned gambling spend: synthesised findings from two online cross-sectional surveys. Addict Behav. 135:107440. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107440.