Abstract

Background

There is emerging evidence that post-traumatic growth is a relevant concept in addiction recovery. However, existing measures, such as the post-traumatic growth inventory, were designed to measure post-traumatic growth in general trauma populations. It is unclear if the post-traumatic growth inventory is suitable for individuals in recovery from substance-related addiction. The current study aimed to qualitatively assess the content validity of the post-traumatic growth inventory for individuals in addiction recovery.

Method

The think-aloud method was applied, and semi-structured interviews utilized, to collect data from 20 individuals in recovery from unhealthy alcohol and/or drug use. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to analyze data in relation to item interpretation and experience of post-traumatic growth.

Findings

Qualitative assessment supported three out of five subscales on the post-traumatic growth inventory (new possibilities, personal strength and appreciation of life). Modifications were suggested on some items from the relating to others domain and responses to the spiritual change domain possibly reflected a cultural influence. There was an identified need to include items that account for positive changes in health behavior.

Conclusions

The current study highlights domains of post-traumatic growth for those in addiction recovery and how the post-traumatic growth inventory may understate some forms of positive life change. Future research should focus on validating a revised version of the post-traumatic growth inventory for this population.

Introduction

Recovery from addiction may be perceived as a daunting challenge for some individuals with long-term and interchangeable patterns of abstinence and relapse (Kougiali et al. Citation2017). Post-traumatic growth (PTG) is a process of transformative change that considers positive by-products, which may emerge during the aftermath of life-changing, traumatic, or stressful life events (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation2004). Irrespective of the type of trauma, PTG can be facilitated when fundamental assumptions and adaptive resources of the individual are significantly challenged (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation2004).

Positive outcomes that emerge during addiction recovery may be explained by the concept of PTG. Previous research found that individuals in recovery from unhealthy alcohol use were flourishing and outperforming comparison groups on measures of happiness, spirituality, optimism and gratitude when they were affiliated with alcoholics anonymous (AA) and had at least 12 months’ sobriety (Krentzman Citation2013). The author proposed a link between engagement in a 12-step program, which focuses on personal growth and PTG (Krentzman Citation2013). Further evidence was provided by Haroosh and Freedman (Citation2017) who assessed PTG in 104 individuals engaging in treatment programs for addiction. Findings indicated those who participated in a 12-step program reported greater spiritual growth and appreciation of life’s potential, alongside higher levels of social support and longer periods of abstinence (Haroosh and Freedman Citation2017). Although some measures used may not have been optimal, this study highlighted how PTG may be a relevant concept in addiction recovery.

Developing a robust measure to assess PTG for individuals in addiction recovery is important to advance the literature. The post-traumatic growth inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation1996) has been commonly used as the standard method of assessing PTG (Frazier et al. Citation2009). The PTGI comprises five domains: relating to others; new possibilities; personal strength; spiritual change and appreciation of life (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation1996). The five-factor structure of the PTGI has been validated with various groups such as veteran samples (Palmer et al. Citation2012), survivors of childhood sexual abuse (Saltzman et al. Citation2015) and stroke patients (Mack et al. Citation2015). However, the PTGI has also shown varying factor structures (e.g. Penagos-Corzo et al. Citation2020; Dubuy et al. Citation2022).

Given that forms of PTG can vary across different groups of individuals and cultures, qualitative methods can help researchers understand how specific groups of individuals interpret items from the PTGI. This is evidenced in studies that assess content validity – the degree to which items represent the assessed construct (Liu et al. Citation2015). Shakespeare-Finch et al. (Citation2013) assessed the content validity of the PTGI with 14 trauma survivors through semi-structured interviews and reported that all items were being consistently understood. Open-ended questions have been utilized in surveys to identify factors related to PTG, which may not be captured by the PTGI. For example, Morris et al. (Citation2012) highlighted additional domains around health-related benefits and compassion for others, and the need for a revised version of the PTGI in cancer survivors. However, it is currently unclear whether there are forms of PTG, which are uniquely experienced in addiction recovery.

The current study aims to assess the content validity of the PTGI among individuals in addiction recovery. There were three research questions: (1) which items and domains of the PTGI are relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible for those in addiction recovery? (2) Do individuals in addiction recovery think there are any modifications required to PTGI items? (3) Are there any forms of PTG which are uniquely experienced by those in addiction recovery and not accurately captured within the PTGI?

Methods

Design

This qualitative study had a cross-sectional design. The think-aloud method was selected as an appropriate form of cognitive interviewing to support the understanding of meaning within subjective and complex cognitive processes (Hauge et al. Citation2015). Semi-structured interviews provided participants with greater flexibility to approach, interpret and explore the PTGI (McIntosh and Morse Citation2015). Reporting of findings was informed by COSMIN guidance for assessing the content validity of patient reported outcome measures (Gagnier et al. Citation2021). Ethical approval was gained from Queen’s University Belfast Engineering and Physical Sciences Faculty Research Ethics Committee (reference number: EPS21_68).

Participants

Typical sample size recommendations in cognitive interview studies range from five to 15 (Peterson et al. Citation2017). We aimed to recruit a sample of 15 to 20 participants, where data saturation was used as a marker for ending recruitment. Selection criteria stated participants must be: over the age of 18, literate in English, able to provide written and verbal consent; and describe themselves as being in recovery from an unhealthy relationship with alcohol and/or drugs for at least six months. Twenty participants from a UK community sample took part. There were 11 females and nine males, with a mean age of 33 years. Purposive stratified sampling was used to include a broad demographic range of participant characteristics (see ).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants (n = 20).

There were two methods of participant recruitment. First, collaborating addiction support services identified eligible participants within their organization, and second, posters were circulated on online/social media platforms. Those who participated were able to elect to enter a prize draw to win one of two £20 Amazon vouchers.

Data collection

Interviews took place between May and July 2021. To adhere to COVID-19 guidance in the UK, interviews were conducted via telephone or video platform based on participant preference. Interested individuals contacted the lead researchers via email if they wished to participate. Eligible participants were provided with a link to Qualtrics, which included access to the participant information sheet and consent form. Once written consent had been obtained, each participant received a copy of the PTGI for their interview.

Participants were asked to read aloud items and response options before talking through their thought process on item suitability. Following this, participants were asked open-ended questions around their experiences of PTG and whether items should be added or removed from the PTGI (see supplementary materials for the full interview schedule). A distress protocol was implemented if a participant experienced negative emotions during the interview. If it was necessary to end an interview, the lead researchers would report this to the chief investigator (PT) who would then decide on appropriate action and which relevant authorities to contact. Before closing the interview and completing a debrief, demographic information was sought from participants.

Two MSc in Clinical Health Psychology students (JM and CB) with prior qualitative methods training conducted the semi-structured interviews, which lasted between 25 and 57 minutes. All interviews were audio recorded and fully transcribed with permission.

Materials

The PTGI (Tedeschi and Calhoun Citation1996) is a 21-item scale that assesses positive post-trauma outcomes across five subscales: relating to others; new possibilities; personal strength; spiritual change and appreciation of life. shows items categorized under relevant domains. Items are answered on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis to 5 = I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis. Higher total scores indicate that individuals have experienced PTG, with each domain score providing further insight on what areas have changed significantly. The PTGI has demonstrated good internal consistency among trauma survivors (Whaley and Mesidor Citation2021). All participants were supplied with a digital copy.

Table 2. PTGI items and their respective domains.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was applied to transcripts (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This approach was considered most appropriate as the study aims focused on perceptions of item suitability, and whether experientially the concept of PTG was adequately captured. The following six steps were completed: (1) three researchers (JM, CB, and NH) transcribed the interviews and repeatedly read the transcripts becoming familiar with the data; (2) two researchers (JM and CB) coded the transcripts with initial labels, which appeared to inform the research questions, codes were revised between subsequent iterations; (3) JM and CB actively examined the coding for broader patterns of meaning and generated initial themes; (4) candidate themes were reviewed in relation to the overall narrative of the data and how they addressed the research questions; (5) individual themes and sub-themes were defined through a detailed analysis of the data and given informative titles; (6) JM and CB produced a final report, which presented themes meaningfully and contextualized to existing literature. To enhance the credibility and transparency of the analysis, wider members of the research team (NH, SC and PT) assessed whether themes were adequately supported by data extracts (Korstjens and Moser Citation2018). QSR NVivo 20 software was utilized for data analysis.

Reflexivity

Reflective journals were kept by the lead researchers to promote continued reflexivity and consider the impact of any biases. JM and CB approached the study with some personal experiences of addiction recovery and professional experiences of working with addiction support services. The lead researchers felt their experiences and awareness of the PTG literature may have elicited some positive preconceptions around PTG being a relevant concept in addiction recovery.

Findings

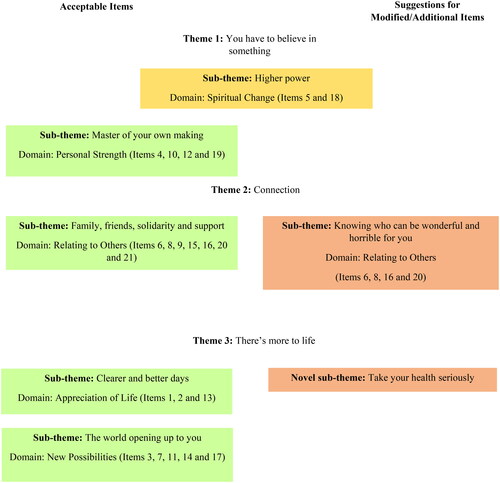

shows three main themes with relevant sub-themes, which were identified in relation to items within the PTGI. Theme titles and supporting quotes are included verbatim from participants to illustrate the findings.

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes related to domains of PTG identified in analysis of think-aloud interviews.

You have to believe in something

This theme represented the ability of the PTGI to capture the significance of having faith and confidence in a spiritual and/or religious belief system, and whether participants had opportunities to reflect and believe in their personal strengths. This theme contained two distinct sub-themes: ‘Higher power’ and ‘Master of your own making’.

Higher power

This sub-theme indicated the relevance of the spiritual change domain for individuals in addiction recovery (items 5 and 18). Five of the older participants (over 34 years old) displayed a spiritual awareness following the aftermath of addiction and attributed this to engagement with activities containing a spiritual component:

I pursued an interest of meditation, mindfulness, and Buddhism to a degree. All things which seemed pretty non-existent in my drinking life. (Participant 4, female, 45–54)

In contrast, the majority of younger participants (under 34 years old) did not report experiencing spiritual and/or religious change. However, these individuals acknowledged the items as being relevant for others in addiction recovery and, therefore, considered them appropriate to remain within the scale:

This wouldn’t be applicable to myself, but I can understand why people going through recovery might have comfort in faith and look for guidance in God and other religions. (Participant 12, female, 25–34)

…to me, that doesn’t suggest about my personal spiritual growth, it suggests about something external that I understand better, which isn’t necessarily the same, and what most of us in recovery would, kind of, understand about spiritual growth… (Participant 14, male, 55–64)

Master of your own making

This sub-theme indicated the relevance of the personal strength domain of the PTGI (items 4, 10, 12 and 19) to those in addiction recovery. Positive outcomes were often associated with higher levels of self-reliance, self-confidence, and self-awareness of their capabilities. There was evidence for this when both male and female participants were able to reaffirm themselves and exhibit a better sense of agency in their lives:

conquering any sort of substance-related dependency is like one of the most self-reliant things you will ever do because nobody else can do it for you. I think it does give you this feeling of being able to tackle anything. (Participant 4, female, 45–54)

Connection

This theme encapsulated responses to seven items from the relating to others domain (items 6, 8, 9, 15, 16, 20 and 21). Positive changes were reported in social relationships and decisions were made to disconnect from toxic relationships. Items from this domain received the highest number of suggested modifications.

Family, friends, solidarity and support

This sub-theme assessed the ability of the PTGI to capture positive changes in social relationships. Many participants reflected on how their attitudes and behaviors positively changed toward close friendships and family members. It was apparent from the findings that active and conscious decisions were being made by male and female participants to spend more time with, or rely more on, family or friends; they were often perceived as people who would understand:

I cherish friendships and they are more meaningful now than they would have been before… (Participant 3, female, 45–54)

Compassion as well for other AA members is very strong at that. I like to see them do well and when they fall or slip, I like to be there and help them if I can without putting myself in danger. (Participant 16, male, 35–44)

Knowing who can be wonderful and who can be horrible for you

Although warmer and more intimate relationships were experienced by all participants, this sub-theme captured instances where individuals acknowledge making decisions to distance themselves from negative relationships. This appeared to act as a catalyst for participants to reevaluate their social relationships in terms of the support they provided:

If they are adding to my life…I can make a conscious decision about who I have and don’t have in my life. (Participant 3, female, 45–54)

They wouldn’t have been there for me or cared if I was in bother and to be honest, they are not the people I would want to have near me if I was in bother. (Participant 18, male, 45–54)

[item 16] could be reworded to be like ‘I know what relationships to put effort into’. (Participant 2, female, 18–24)

There’s more to life

This theme represents how the PTGI captures the relevance of the appreciation of life and new possibilities domains. The importance of having items on health behavior changes was suggested by male and female participants. The findings reflect that valuing one’s life, reevaluating possible paths and safeguarding one’s health are brought out from the addiction recovery process.

Clearer and better days

This sub-theme considered three items from the appreciation for life domain (items 1, 2 and 13) and this was another aspect of PTG that addiction recovery clarified for most participants. Some participants reflected on the fragility of life and how it should not be taken for granted. Others perceived their addiction recovery to be thought-provoking or felt empowered to use their newfound confidence to make the most of their days:

It was the closest I ever came to dying so yeah it just gave me a completely different perspective on life. (Participant 4, female, 45–54)

How can you not appreciate each day when you’re not addicted? (Participant 15, male, 35–44)

The world opening up to you

This sub-theme considered how the PTGI captured responses to five items from the new possibilities domain (items 3, 7, 11, 14 and 17). Male and female participants noted that recovery provided scope to consider new paths or reevaluate previous paths in their lives. Around half of the participants appeared to seize new opportunities and interests:

Guided meditation, it’s something I would have never ever even dreamt of doing. (Participant 15, male, 35–44)

I didn’t really develop any new interests. I think I just embraced my previous interests with much more enthusiasm. (Participant 4, female, 45–54)

Take your health seriously

This sub-theme captures specific health-related benefits and changes encouraged by addiction recovery. Around one-third of the participants indicated the importance of prioritizing a healthy lifestyle. Positive outcomes included improved sleep, changes in dietary behavior and increased monitoring of one’s physical and mental health:

I can eat and I can sleep, and before I wouldn’t have been eating or sleeping. I could have gone five days and not ate, and it just left me in a total and utter mess. (Participant 16, male, 35–44)

Since I’ve been able to gain a level of control over alcohol, I can manage my mental health better and I’m far more accepting of it and how I manage it. (Participant 18, male, 45–54)

Response options on the PTGI

Almost all participants felt that the scale was clear, easily understood and provided a relevant range of responses to reflect their answers. One participant felt the response options should range from 0 to 10 rather than 0 to 5 but they acknowledged that it depended on what type of data was required. Therefore, the six-point Likert scale was regarded as being relevant and appropriate.

Thematic summary

Overall, most participants felt the PTGI was largely relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible in capturing PTG. summarizes items and domains that were considered by participants to be appropriate in their current form, modifiable, or novel. No reasons were given to remove any PTGI items. All participants had an appreciation that items were either relevant for themselves or others in addiction recovery:

All of them are relevant because everyone’s situation is different. There’s a lot of those that did apply to me, there’s some that didn’t. But I can see the value from another person’s perspective. (Participant 10, male, 25–34)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively assess the content validity of the PTGI for those in addiction recovery. The think-aloud method provided a detailed analysis of the PTGI, and it was clear that items were being consistently understood as intended.

Relating to others was described as engaging more with friends, family, or those who have had similar experiences and disengaging with those exerting a negative influence on addiction recovery. New possibilities were created when new or different paths were explored in one’s life. Personal strength involved the idea of having higher levels of self-reliance, self-confidence, and self-awareness of one’s capabilities. Many participants did not endorse spiritual change as a form of PTG; however, it was acknowledged as being potentially important for others in addiction recovery. This finding is consistent with previous research in general trauma populations (Shakespeare-Finch and Copping Citation2006; Shakespeare-Finch et al. Citation2013). Appreciation of life was described as having a different perspective during recovery and a second chance to cherish things that life has to offer.

The current study did not observe different gendered responses to PTGI items or domains in relation to addiction recovery. However, it was evident the PTGI did not capture all aspects of PTG, with some participants reporting positive changes in health behavior by placing importance on managing their physical and mental health to sustain their addiction recovery. This aligns with a previous pilot study by Akhtar and Boniwell (Citation2010), which reported improvements in wellbeing among adolescents who were heavy alcohol users when there was a reduction in their use. Health-related benefits in relation to PTG have also been more widely reported in illness contexts such as with cancer patients (Morris et al. Citation2012; Heidarzadeh et al. Citation2018) and survivors of life-threatening illnesses (Hefferon et al. Citation2009). Additional items around changes in health behavior can be incorporated into Calhoun and Tedeschi’s (Citation2014) model of PTG and this should be explored further for those in addiction recovery.

It is noteworthy that modifications were suggested on four items from the relating to others domain of the PTGI. Both male and female participants expressed how distancing themselves or ending certain social relationships could be a positive indicator of improved relationships. It was felt the wording of these items may not entirely accommodate social relationships which needed to end to aid addiction recovery. Previous research has found that individuals in recovery from unhealthy drug use may show ‘decreased naivete’ toward negative social relationships (McMillen et al. Citation2001). Furthermore, Hall’s (Citation2003) study on women who were abused by partners or family members reported that being cautious around relationships and less reliant on others was reflective of growth in response to trauma. Given that both male and female participants reported similar relational responses, items from the relating to others domain could therefore be modified to capture more complex relational dynamics for those experiencing growth from addiction recovery.

Many participants did not report spiritual and/or religious growth. This finding is consistent with evidence that distal culture in the West may influence perceptions of spiritual change (Copping et al. Citation2008). Previous research has acknowledged the potential for secular samples to report a floor effect within this domain (Vázquez and Páez Citation2010; Ho et al. Citation2013). One participant suggested items should consider internal aspects of spiritual growth. Tedeschi et al. (Citation2017) have addressed this issue and integrated four additional items into the spiritual change domain, which consider broad reflections on matters related to mortality, harmony, and interconnection with others. The expanded inventory (PTGI-X) may have uncovered more diverse perspectives of PTG as traditional religious beliefs were recognized as being less dominant in the current study.

Study limitations

Although representativeness or generalizability are not concepts usually aligned with qualitative research, there are some notable limitations to the current study in terms of participant characteristics. There is a lack of ethnic diversity with all participants identifying as White; therefore, the potential disparities faced by people of color were not captured. Also, information on socioeconomic status was not recorded and thus intersectional factors were not considered. For example, Lappan et al. (Citation2020) reported higher dropout rates from substance use treatments in studies which included African Americans and lower income individuals. Over half the sample were under 34 years old and, therefore, it is predominately composed of younger adults. Also, only 10% of participants defined recovery as abstinence form all substances. This is an important consideration as common support networks, for example, AA, implement a 12-step abstinence-based approach with a spiritual component, and there is an established relationship between PTG in addiction recovery and engagement with 12-step programs (Krentzman Citation2013; Haroosh and Freedman Citation2017).

It should be acknowledged that the selection criteria only stated that participants must perceive themselves to be in recovery from an unhealthy relationship with alcohol/drugs for at least six months. As 40% of participants defined recovery as being moderated or controlled alcohol/drug use, it is possible the PTGI could have been interpreted differently by those with varied histories of unhealthy use or substance use disorder (SUD). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5, a non-abstinence-based definition would not be aligned to recovery from severe symptoms of SUD (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). Despite this limitation, the research team engaged closely with support services to ensure those who had received formal treatment were represented. If stricter selection criteria were imposed, the insight of those who did not require formal treatment may not have been captured. This is important as natural recovery occurs for many individuals who do not seek formal treatment for their unhealthy use (Kelly et al. Citation2019; MacKillop Citation2020).

Finally, the recruitment strategy posed a possible risk of selection bias. Most individuals who volunteered to be interviewed were inclined to be in a positive stage of addiction recovery and experiencing some forms of growth captured by the PTGI. Prospective studies including cohorts in the early stages of recovery or who have recently experienced relapse would be important groups to appraise the PTGI in future research.

Implications

Developing research tools that can accurately monitor forms of PTG has implications for researchers, clinicians and those in addiction recovery (Boswell et al. Citation2015). This could assist in building confidence that PTG is a recognized concept in addiction recovery and support the development and adaptation of interventions which enable individuals to sustain their recovery more effectively (Ogilvie and Carson Citation2022).

Recommendations

This research recommends how the PTGI could be optimized for those in addiction recovery. First, there is a need to incorporate items around positive changes in health behavior. For example, by utilizing the ‘capability, opportunity, motivation and behavior’ (COM-B) model of behavior change, additional items could be generated (Michie et al. Citation2011). Second, items from the relating to others domain could be modified to accommodate broader indicators of improved relationships. Third, given the potential for the spiritual change domain to be underreported, it is important to use an expanded version (e.g. PTGI-X), which accounts for spiritual existential life changes in secular samples (Tedeschi et al. Citation2017). Finally, future research should assess the content validity of the PTGI with a more homogenous sample who previously received a formal diagnosis of SUD and are in active addiction recovery.

Conclusions

PTG is a multidimensional construct for individuals in addiction recovery. Three out of five subscales on the PTGI (new possibilities, personal strength and appreciation of life) were supported in their current format. Modifications were suggested on four items from the relating to others domain, and responses on the spiritual change domain possibly reflected a cultural influence. There is an identified need for additional items around positive changes in health behavior. Future research should focus on validating a revised version of the PTGI for individuals in addiction recovery.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences at Queen’s University Belfast on 31 March 2021 (reference number: EPS21_68). Participants provided informed verbal and written consent prior to beginning the interview.

Author contributions

PT and SC were responsible for the conception and design of the work. JM, CB and NH were responsible for data collection. All authors were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data. JM and CB drafted the manuscript and made revisions advised by PT and the research team.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who gave up their time to participate.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akhtar M, Boniwell I. 2010. Applying positive psychology to alcohol-misusing adolescents. Groupwork. 20(3):6–31. doi: 10.1921/095182410X576831.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Vol. 5. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Boswell JF, Kraus DR, Miller SD, Lambert MJ. 2015. Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychother Res. 25(1):6–19. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.817696.

- Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. 2014. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: an expanded framework. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and Practice. New York: Routledge; p. 3–23.

- Copping A, Shakespeare-Finch J, Paton D. 2008. Modelling the experience of trauma in a white-Australian sample. In: Proceedings of the 43rd Australian Psychological Society Annual Conference; Sep 23–27; Hobart, Australia. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Psychological Society. p. 130–134.

- Dubuy Y, Sébille V, Bourdon M, Hardouin JB, Blanchin M. 2022. Posttraumatic growth inventory: challenges with its validation among French cancer patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 22(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01722-6.

- Frazier P, Tennen H, Gavian M, Park C, Tomich P, Tashiro T. 2009. Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychol Sci. 20(7):912–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02381.x.

- Gagnier JJ, Lai J, Mokkink LB, Terwee CB. 2021. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 30(8):2197–2218. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02822-4.

- Hall JM. 2003. Positive self-transitions in women child abuse survivors. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 24(6–7):647–666. doi: 10.1080/01612840305325.

- Haroosh E, Freedman S. 2017. Posttraumatic growth and recovery from addiction. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 8(1):1369832. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1369832.

- Hauge CH, Jacobs-Knight J, Jensen JL, Burgess KM, Puumala SE, Wilton G, Hanson JD. 2015. Establishing survey validity and reliability for American Indians through “think aloud” and test–retest methods. Qual Health Res. 25(6):820–830. doi: 10.1177/1049732315582010.

- Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N. 2009. Post‐traumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol. 14(Pt 2):343–378. doi: 10.1348/135910708X332936.

- Heidarzadeh M, Rassouli M, Brant JM, Mohammadi-Shahbolaghi F, Alavi-Majd H. 2018. Dimensions of posttraumatic growth in patients with cancer: a mixed method study. Cancer Nurs. 41(6):441–449. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000537.

- Ho SM, Law LS, Wang GL, Shih SM, Hsu SH, Hou YC. 2013. Psychometric analysis of the Chinese version of the posttraumatic growth inventory with cancer patients in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Psychooncology. 22(3):715–719. doi: 10.1002/pon.3024.

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG, White WL, Hoeppner BB. 2019. How many recovery attempts does it take to successfully resolve an alcohol or drug problem? Estimates and correlates from a National Study of Recovering US Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 43(7):1533–1544. doi: 10.1111/acer.14067.

- Kougiali ZG, Fasulo A, Needs A, Van Laar D. 2017. Planting the seeds of change: directionality in the narrative construction of recovery from addiction. Psychol Health. 32(6):639–664. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1293053.

- Krentzman AR. 2013. Review of the application of positive psychology to substance use, addiction, and recovery research. Psychol Addict Behav. 27(1):151–165. doi: 10.1037/a0029897.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. 2018. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 24(1):120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092.

- Lappan SN, Brown AW, Hendricks PS. 2020. Dropout rates of in‐person psychosocial substance use disorder treatments: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction. 115(2):201–217. doi: 10.1111/add.14793.

- Liu JE, Wang HY, Hua L, Chen J, Wang ML, Li YY. 2015. Psychometric evaluation of the simplified Chinese version of the posttraumatic growth inventory for assessing breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 19(4):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.01.002.

- Mack J, Herrberg M, Hetzel A, Wallesch CW, Bengel J, Schulz M, Rohde N, Schönberger M. 2015. The factorial and discriminant validity of the German version of the post-traumatic growth inventory in stroke patients. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 25(2):216–232. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2014.918885.

- MacKillop J. 2020. Is addiction really a chronic relapsing disorder? Commentary on Kelly et al. “How many recovery attempts does it take to successfully resolve an alcohol or drug problem? Estimates and correlates from a National Study of Recovering US Adults”. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 44(1):41–44. doi: 10.1111/acer.14246.

- McIntosh MJ, Morse JM. 2015. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2:2333393615597674. doi: 10.1177/2333393615597674.

- McMillen C, Howard MO, Nower L, Chung S. 2001. Positive by-products of the struggle with chemical dependency. J Subst Abuse Treat. 20(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00151-3.

- Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. 2011. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J, Scott JL. 2012. Posttraumatic growth after cancer: the importance of health-related benefits and newfound compassion for others. Support Care Cancer. 20(4):749–756. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1143-7.

- Ogilvie L, Carson J. 2022. Trauma, stages of change and post traumatic growth in addiction: a new synthesis. J Subst Use. 27(2):122–127. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2021.1905093.

- Palmer GA, Graca JJ, Occhietti KE. 2012. Confirmatory factor analysis of the posttraumatic growth inventory in a veteran sample with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Loss Trauma. 17(6):545–556. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2012.678779.

- Penagos-Corzo JC, Tolamatl CR, Espinosa A, Lorenzo Ruiz A, Pintado S. 2020. Psychometric properties of the PTGI and resilience in earthquake survivors in Mexico. J Loss Trauma. 25(4):364–384. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2019.1692512.

- Peterson CH, Peterson NA, Powell KG. 2017. Cognitive interviewing for item development: validity evidence based on content and response processes. Meas Eval Counsel Dev. 50(4):217–223. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2017.1339564.

- Saltzman LY, Easton SD, Salas-Wright CP. 2015. A validation study of the posttraumatic growth inventory among survivors of clergy-perpetrated child sexual abuse. J Society Soc Work Res. 6(3):305–315. doi: 10.1086/682728.

- Shakespeare-Finch J, Copping A. 2006. A grounded theory approach to understanding cultural differences in posttraumatic growth. J Loss Trauma. 11(5):355–371. doi: 10.1080/15325020600671949.

- Shakespeare-Finch J, Martinek E, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. 2013. A qualitative approach to assessing the validity of the posttraumatic growth inventory. J Loss Trauma. 18(6):572–591. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2012.734207.

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. 1996. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Traum Stress. 9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305.

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. 2004. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 15(1):1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01.

- Tedeschi RG, Cann A, Taku K, Senol‐Durak E, Calhoun LG. 2017. The posttraumatic growth inventory: a revision integrating existential and spiritual change. J Trauma Stress. 30(1):11–18. doi: 10.1002/jts.22155.

- Vázquez C, Páez D. 2010. Posttraumatic growth in Spain. In: Weiss T, Berger R, editors. Posttraumatic growth and culturally competent practice: lessons learned from around the globe. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; p. 97–112.

- Whaley AL, Mesidor JK. 2021. Implications of posttraumatic growth for the treatment of comorbid substance abuse among survivors of traumatic experiences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 126:108289. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108289.