?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Digital nomads live a new way of life that creates an ideal balance of work and leisure. Research on the phenomenon of digital nomads is still in its early stages and is not fully framed as a proper research category. Therefore, the present research aims to explore research on digital nomadism by study leading countries, authors and themes that can become a foundation for future research. This study is exploratory and interpretive – using bibliometrics, we systematically searched all articles indexed in the Web of Science database. The study presents the evolution of scholarly production, and identifies key authors and countries that have the potential to become pioneers in digital nomad research. We identified 17 core concepts of digital nomad research as well as concepts that have not yet received much attention from scientists. Additionally, our study provides a framework for research on digital nomadism and presents topics for future research: we determine how the 17 core concepts identified in this study affect the lives of digital nomads, research into legislation that directly affects digital nomads, study how COVID-19 has changed working styles, and offer a bibliometric analysis of data on digital nomads from other databases.

Introduction

The development of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and globalization has opened the possibility of new flexible working arrangements. In today’s world, it is common to work remotely using digital technologies (Kathleen et al., Citation2021; Thompson, Citation2019). Especially now, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, flexible work arrangements have been adopted as a standard practice in many industries (Davison, Citation2020; Druta et al., Citation2021; Frost & Duan, Citation2020; Meluso et al., Citation2020; Newman & Ford, Citation2020). COVID-19 has brought together diverse groups of team members worldwide with a wide range of skills, expertise, and backgrounds (Marques et al., Citation2021). However, remote working is nothing new; it was certainly possible before the COVID-19 pandemic. People have been working remotely for many years. Today, people are looking for opportunities to combine work and travel either to gain skills or simply to have exciting and fun experiences. Many companies today offer remote working to increase the job satisfaction of their employees. Remote working may improve performance as well as increase the likelihood of attracting excellent employees (Demaj et al., Citation2021), reduce overhead costs and travel costs for businesses (Bjørn & Ngwenyama, Citation2009; Thompson, Citation2018), and access talented people worldwide (Aldag & Kuzuhara, Citation2015; Marques et al., Citation2021).

Remote forms of work also have disadvantages. The legal regulation of flexible employment relationships remains difficult for some companies due to inflexible labour codes. Some countries do not allow employees to work outside their designated workplace. Tax rules based on residence can also be problematic (Tyutyuryukov & Guseva, Citation2021). Moreover, communication issues are a frequently discussed factor in the success of remote collaboration (Aldag & Kuzuhara, Citation2015; Gilson et al., Citation2013). Other challenges include establishing trust (Jawadi, Citation2013), cultural differences (Aldag & Kuzuhara, Citation2015; Powell et al., Citation2004) and knowledge sharing (Eisenberg & Mattarelli, Citation2017; Jarrahi et al., Citation2019). Often people take advantage of remote working opportunities, and they work from exotic destinations (Dal Fiore et al., Citation2014) or destinations that align with their specific work needs and lifestyle (Mladenovic, Citation2016). Thus, when managed properly, remote work and travel can offer ideal combinations of work-life balance and work-leisure lifestyle (Orel, Citation2019). Makimoto and Manners (Citation1997) coined the term “digital nomads” for this type of workers.

Towards a definition of digital nomads

To understand digital nomadism as a new form of rapidly expanding mobility and a recent social phenomenon, it is necessary to further conceptualize the topic (Hannonen, Citation2020). Digital nomads are primarily young (Millennials or Generation Z) individuals who are motivated to explore and combine travel with virtual work (Reichenberger, Citation2018). According to Hensellek and Puchala (Citation2021), all definitions of digital nomads have common factors: digital work, flexibility, mobility, identity, and community. Similarly, Demaj et al. (Citation2021) claim that nomadism is linked to digitalization because digital nomads are people who can work while moving from one place to another simply by having one mobile device and connection to the internet. Another definition describes digital nomads as “internet-enabled remote workers, who focus on connectivity and productivity even in leisure” (Bozzi, Citation2020). The importance of digital technologies and infrastructures for digital nomads is also confirmed by Nash et al. (Citation2018) and Lee et al. (Citation2019). But as Hannonen (Citation2020) argues “the use of technology on the road does not make one a digital nomad. It requires the accomplishment of the work-related and professional activities while traveling”. Thus in addition to use of digital technologies, Nash et al. (Citation2018), offers a definition of digital nomads that highlights three other key elements – gig work, nomadic work, and global travel adventure. de Almeida et al. (Citation2021) created a conceptual framework for digital nomads that includes use of tech as well as personal life and social dimensions. Orel (Citation2019) suggests that digital nomads are people who have an optimal work/leisure ratio, who value freedom of movement quite highly, and who like to work in community-oriented workspaces.

Müller (Citation2016) understands the digital nomad as a social figure who combines work with a new vision of personal life, usually an entrepreneur or a location-independent freelancer, and he offers two research streams on digital nomads. The first stream of research examines digital nomads as individual travellers, e.g. “flashpackers” – people who travel with all the necessary digital equipment for their work, wherever their heart takes them. The second stream of research that Müller (Citation2016) described is a view of digital nomads as labour mobility. In this case, people become nomads due to moving for work. Based on a comparison of many definitions, Hannonen (Citation2020) provides the following description of digital nomads: “The term refers to a rapidly emerging class of highly mobile professionals, whose work is location independent. Thus, they work while travelling on (semi)permanent basis and vice versa, forming a new mobile lifestyle”. Digital nomads are highly motivated and free-spirited people (Macgilchrist et al., Citation2020) who are changing the perception of what is considered a good livelihood (Demaj et al., Citation2021). Finally, Richards (Citation2015) delineates three types of digital nomads: the backpacker, the flashpacker and the global nomad.

Commonly, telecommuters, freelancers, location-independent workers, remote workers and online entrepreneurs are also referred to as digital nomads, and these various terms are mistakenly used as synonyms for digital nomads. This creates terminological confusion (Hannonen, Citation2020). The distinction between remote working, telecommuting and digital nomadism is important when conceptualizing the concept of the digital nomad (Hannonen, Citation2020). Nash et al. (Citation2021) points out other inaccuracies in defining digital nomads by highlighting that labelling digital nomads merely as location-independent workers is misleading. They argue that it is critical for digital nomads to be able to find or create a suitable workspace that matches individual preferences and technological requirements.

Given the presented definitions and their limitations, in this paper, we understand digital nomads as individuals with a mobile lifestyle that combines work and leisure, requiring a particular set of skills and equipment.

How does research respond to digital nomadism?

A large body of literature focuses on specific local areas that are attractive to digital nomads. For example, Cruz et al. (Citation2021) study the co-working spaces in Proto City. Another study by Foley et al. (Citation2022) deals with sustainability and digital nomadism in the so-called Small Island Developing States, which are also a frequent target of digital nomads. Green (Citation2020), de Loryn (Citation2022), and Mancinelli (Citation2020) describe digital nomads’ situation in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Korjus et al. (Citation2017) illustrate the perspectives from Estonia. MacRae (Citation2016) and Woldoff and Litchfield (Citation2021), adding the community perspective in Ubud. Hannonen (Citation2020) points out that places like Chiang Mai and Bali are the places that meet the needs of digital nomads.

Researchers also study co-working spaces, which are the favourite options of digital nomads (Chevtaeva & Denizci-Guillet, Citation2021; Cruz et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2019; Orel, Citation2019, Citation2021). Other research has explored the lifestyles of digital nomads. As Demaj et al. (Citation2021) mentioned, digital nomads do not wake up every day stuck in traffic to get to work; they are changing the presumption of what we consider as a good living. Digital Nomads are highly self-determined and free people (Macgilchrist et al., Citation2020). They often share their way of living on social media (Bozzi, Citation2020; Macgilchrist et al., Citation2020). Digital nomads are studied from the aspect of employment (Thompson, Citation2018), well-being (Korpela, Citation2020; von Zumbusch & Lalicic, Citation2020), motivation (Cook, Citation2020; Hall et al., Citation2019) and knowledge management (Jarrahi et al., Citation2019).

As Reichenberger (Citation2018) stated, the phenomenon of digital nomads is not yet well established. Similarly, Nash et al. (Citation2018) pointed out that the body of empirical and academic research into digital nomadism is very small. Also, Hannonen (Citation2020) stated that even though the study of digital nomads is growing, the term is used in many different, often contradictory ways (de Almeida et al., Citation2021). Knowledge of digital nomads is also often limited or even biased (Reichenberger, Citation2018) because the sources of information are commonly not academic, peer reviewed papers, but merely online blogs, newspapers, interviews, etc. (Nash et al., Citation2018). As Hannonen (Citation2020) mentioned, digital nomadism is not yet framed as a proper research category. For these reasons, we explore the research on digital nomadism by studying leading countries, authors and themes that can serve as a foundation for future research. The presented paper uncovers the underlying concepts of digital nomadism, as well as identifies leading countries and authors, and their evolution over time so as to reveal possibilities for future research. This study is exploratory and interpretive – using bibliometrics, we systematically searched all articles indexed in the Web of Science database (WOS).

Materials and methods

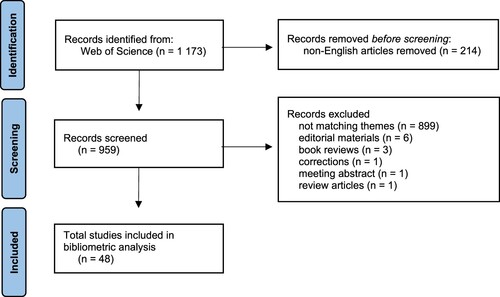

We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) diagram created by Page et al. (Citation2021) to describe our search process (see ). First, we obtained records from the WOS databases. WOS was chosen because it is considered the most selective database (Singh et al., Citation2021) and, therefore, we assume that the records in WOS are the highest quality research papers. We retrieved the data on March 4th, 2022, with the following search query:

Our search returned 1173 bibliographic references. In total, we removed 214 non-English articles. In the first round of the analysis, we screened the titles and abstracts of the articles. The selection criteria were based on the research questions (we removed all reports that did not match the research objective, book reviews, editorial materials, corrections, meeting abstract, and review articles). Among the records excluded for not matching themes were records that dealt with e.g. the historical view of nomads (pastoral nomads, trader nomads), records dealing with nomadic livestock-production or even research on nomadic football players, etc.

The second step was a bibliometric analysis of the 48 studies that match our research questions. For our bibliometric analysis we used RStudio, package Bibliometrix, and Biblioshiny app (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017). First, we described the basic information about the annual scientific production and the authors. We analysed the most productive and influential authors based on the number of articles they have written and the number of citations they have received (Aria et al., Citation2020; Cuccurullo et al., Citation2016). Second, we analysed the most productive countries, including the scientific collaboration between countries. Third, we evaluated international cooperation based on publications that emerge as international co-authored publications (Aria et al., Citation2020). We calculated the country collaboration rate (CCR). According to Aria et al. (Citation2020), the CCR is calculated as the ratio between the multiple country publication (MCP) and total publication (TP). We provided information about publications that had been created within one country (single country publication – SCP). We have also captured the evolution of trends topics (based on the authors’ keywords). Last, we performed multiple correspondence analyses and K-means clustering to divide publications into clusters (based on the authors’ keywords). To avoid bias, we merge synonyms (digital nomad = digital nomads, digital nomadism; mobility = lifestyle mobility, mobilities).

Results

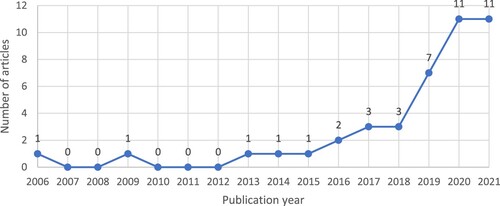

The first publication on digital nomads indexed in WOS is from 2006. The article titled Abductive reasoning and ICT enhanced learning: Towards the epistemology of digital nomads by Patokorpi (Citation2006). In this article, Patokorpi (Citation2006) reflects on elements of constructivist pedagogy using ICT to educate digital nomads. As shown in , the number of publications on digital nomads in WOS then stagnated until 2015. As Richards (Citation2015) pointed out, the blurring of the line between work and leisure, combined with the rise of digital technology, has given this community the ability to work anywhere they can connect to the internet. Richards (Citation2015) also defined the importance of research on digital nomads, which points to distinctions between different types of nomads (and specifically in young individuals). This argument was followed by studies by Reichenberger (Citation2018) and Nash et al. (Citation2018), which provided some of the first conceptualizations of digital nomadism and outlined digital nomadism as a research category. In 2018, digital nomadism was also included as a stand-alone category in the State of Independence in America annual research report (Hannonen, Citation2020). These highlights are behind the increase in digital nomad publications we see after 2018. The annual growth rate is 24.36%.

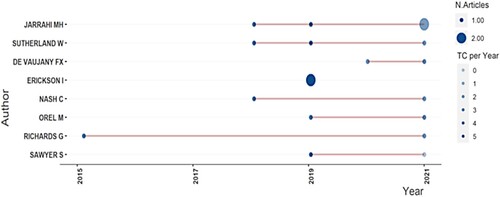

Most publishing authors and their impact can be used to understand better the field’s past development (Cuccurullo et al., Citation2016). Our dataset included 48 publications written by 107 authors (average of 2.46 co-authors per publication). Of the total, 18 publications were single-authored. The average article in the field of digital nomads was cited 6,792 times in WOS. Over time, the most influential authors (see ) are Mohammad Hossein Jarrahi (4 publications from 2018 to 2021), followed by Will Sutherland (3 publications from 2018 to 2021). In , the bubble size represents the number of publications written by each author in a given year (in this case the values are one or two – the authors wrote a maximum of two articles per year), the intensity of colour indicates the total number of citations per year – TC per year (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017).

Sharing knowledge and gaining inspiration and new ideas from colleagues is common in academic life. Therefore, it is not surprising that two or more authors have collaborated to write most publications. It can happen that authors are from different institutions or even countries. Therefore, international co-authored articles are published, and thus they can be used to evaluate international collaboration (Aria et al., Citation2020; Leydesdorff et al., Citation2013). In this, the most productive country is the U.S.A., followed by Russia and the U.K. (see ). The countries with the most international cooperation (highest CCR) are Germany, the U.K. and the U.S.A.

Table 1. Production of publication by country (only countries with three and more publications per country are listed).

The results also show that researchers focus on different destinations that are popular among digital nomads. Thus, these studies provide unique insights into local issues faced by nomads. Of the 48 studies, 23 did not specify the countries studied (mostly literature reviews or studies analysing social networks), and 10 studies indicated that research was conducted in multiple countries. The most studied nation is Thailand with 5 study (Cook, Citation2020; de Loryn, Citation2022; Green, Citation2020; Mancinelli, Citation2020; Orel, Citation2021), followed by Russia with 2 study (Alekseevna et al., Citation2019; Tyutyuryukov & Guseva, Citation2021). Nations that were a focus of a single study include Brazil (Jung & Buhr, Citation2021), Estonia (Korjus et al., Citation2017), India (Korpela, Citation2020), Indonesia (MacRae, Citation2016), Israel (Al-Zobaidi, Citation2009), Oman (Al-Hadi & Al-Aufi, Citation2019), Portugal (Cruz et al., Citation2021), Romania (McElroy, Citation2020) and United Kingdom (Andrejuk, Citation2022).

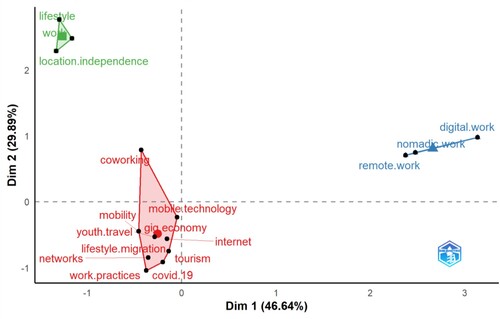

Based on the authors’ keywords, the analysis divided core themes into three clusters (). The size of the cluster (coloured area and number of dots) determines how many publications addressed issues within the cluster. The interpretation of the conceptual structure map results is determined by the relative position of the points and their distribution along the dimensions. Aria and Cuccurullo (Citation2017) state that the more similar the authors’ keywords are in distribution, the closer they appear on the map. At the same time, the closer the points are to the 0:0 coordinates, the more research has addressed the theme. The largest cluster (red colour) merges themes that are connected with digital nomad everyday life (themes from tourism and mobility, youth travel, and lifestyle migration to work practices, co-working, gig economy, or even COVID-19). The blue cluster describes research themes that deal with distinguishing the differences between digital, nomadic and remote work. The last green cluster is one of themes that describe the life of the digital nomad – location independence, work and lifestyle.

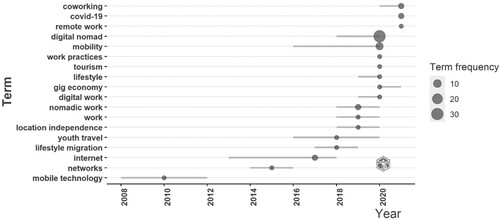

To capture the evolution of the themes of the digital nomad, we continue analyzing author keywords. As shown in , until 2017 the themes that were addressed were primarily related to the technical infrastructure of digital nomad (mobile technology, networks, internet). One very influential article from this period was by Dal Fiore et al. (Citation2014), which looked at how mobile technology fosters travel. This study predicted that “in the age of ‘digital nomadism’, mobile technology is likely to play an important role for the new mobility and work-life arrangements put into practice by a multitude of creative knowledge professionals”. Another important research was a global survey of young travellers conducted by Richards (Citation2015), which indicated three primary youth travel styles – the backpacker, the flashpacker and the global nomad. Between 2018 and 2020, digital nomadism was discussed as a lifestyle that combines work with migration and lifestyle (Hall et al., Citation2019; Orel, Citation2019; Reichenberger, Citation2018). Some articles also dealt with conceptualizing the phenomenon of digital nomads (Hannonen, Citation2020; Korpela, Citation2020; Mancinelli, Citation2020; Nash et al., Citation2018; Reichenberger, Citation2018). Other research studied the work of digital nomads and its specifics, such as working with information (Al-Hadi & Al-Aufi, Citation2019) or knowledge (Jarrahi et al., Citation2019) as well as working in co-working places (Orel, Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2019). In 2020, the amount of research and so also the number of core themes grew. The most important core themes were gig economy, lifestyle and tourism (Bozzi, Citation2020; Cook, Citation2020; Willment, Citation2020), work practices (Aroles et al., Citation2020; Green, Citation2020; Nikolaeva & Kotliar, Citation2019). The COVID-19 pandemic left its mark even in research into digital nomads. For example, Richards and Morrill (Citation2021) studied changes in youth travel in the beginning of the pandemic and confirmed that youth tourism businesses were severely affected. de Almeida et al. (Citation2021) studied posts on Reddit and found that the COVID-19 pandemic was also seen as an opportunity to experience the lifestyle of digital nomads. Beyond the pandemic, the topic of co-working was also raised in 2021. At this time, co-working was perceived as a business opportunity, and was included in the tourism agenda (Chevtaeva & Denizci-Guillet, Citation2021). Digital nomads and co-working and its impact on society have also been examined from the perspective of organizational studies (Cnossen et al., Citation2021) and migration (Jung & Buhr, Citation2021), but also from the perspective of responsible, ecological and sustainable society (Cruz et al., Citation2021).

The themes illustrated in and are core themes of research into digital nomads. The researchers addressed 17 themes that define the concept of digital nomads (COVID-19, co-working, digital work, gig economy, internet, lifestyle, lifestyle migration, location independence, mobile technology, mobility, networks, nomadic work, remote work, tourism, work, work practices and youth travel). As shown in the Conceptual Structure Map (), these core themes can be further divided into three areas of interest. These areas (clusters) form a framework for research into digital nomads. The first area of research on digital nomads includes publications focusing on the definition and distinction between remote, nomadic and digital work. The second includes publications on changing life and work styles in relation to location independence. And the third includes publications addressing the factors that define and affect the lives of digital nomads. Based on these results, it is possible to identify themes that have not yet but need to become a focus of future research. One such area is that of policymaking; identifying specific changes to legislation that would make life more settled for digital nomads is an as of yet unexplored potential core theme of research. Likewise, few scholars have discussed the economic and taxation factors of nomadic life. Last but not least, we see too little research in the intersection of digital nomadism and social media – digital nomads often use social media to share their nomadic lifestyle.

Discussion

Although the term digital nomad first appeared in 1997, used by Makimoto and Manners in the WOS database, the first research article into the phenomenon only appears in 2006. Reichenberger (Citation2018) and Thompson (Citation2018) have already observed the low degree of scientific attention given this area. But as stated by Hannonen (Citation2020) and as our results show, the number of publications is steadily growing.

As our research is the first bibliometric analysis of the domain of digital nomadism, it is not possible to compare the results obtained from WOS with others. However, it is possible to draw general conclusions for discussion. In accordance with the present results, previous studies have demonstrated that the U.S.A. is the most productive country terms of the number of publications on digital nomads (Shehatta & Al-Rubaish, Citation2019). According to our results and in contrast to earlier findings (Shehatta & Al-Rubaish, Citation2019), Russia is the second most productive in terms of the number of publications on digital nomads. Shehatta and Al-Rubaish (Citation2019) agree on third place for the United Kingdom. To compare the productivity of different countries in this field, we can also look to fields that are similar to the domain of digital nomadism. Abarca et al. (Citation2020) carried out a bibliometric study on working in virtual teams. His results show that the U.S.A. is the most productive country, followed by the U.K. and Germany (Abarca et al., Citation2020). Overall, the U.S.A. is the most productive country in publishing – as is confirmed by our research and the research of others (Abarca et al., Citation2020; Shehatta & Al-Rubaish, Citation2019). Co-authored papers are commonly used to indict international collaboration (Aria et al., Citation2020; Leydesdorff et al., Citation2013). Therefore, it can be assumed that the countries with the highest CCR in our research (Germany, the U.K. and the U.S.A.) will become international leaders in the field of digital nomad research. Digital nomads are not yet grounded as a research area (Hannonen, Citation2020). Therefore, the results of our research about the most productive authors suggest that their publications will serve as and establish the foundations of the research field of digital nomads.

Three areas of research on digital nomads

Our results divided the core research concepts into three clusters – everyday life of the digital nomad, the nomadic lifestyle, and the difference in digital, nomadic and remote work. Red cluster (everyday nomadic life) refers to the issues of the remote work of digital nomads and its impact on the outside world. The publications in this cluster address themes such as nomadic working practices and the fundamentals of digital nomadism – mobility (Dal Fiore et al., Citation2014; Hall et al., Citation2019; Jung & Buhr, Citation2021) and tourism (Bozzi, Citation2020; Nash et al., Citation2018; Orel, Citation2021; Willment, Citation2020). Other studies focus on youth travel (Alekseevna et al., Citation2019; Richards, Citation2015; Richards & Morrill, Citation2021). Studies in the red cluster also focus on the working environment of digital nomads – co-working spaces (Cruz et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2019; Orel, Citation2019) and social networks (Bozzi, Citation2020; Cnossen et al., Citation2021; Philippou, Citation2013). The publications within the red cluster focus not only on the work and environment of digital nomads but also on the factors that enable digital work – such as the internet and mobile technologies (Dal Fiore et al., Citation2014; de Loryn, Citation2022; Jung & Buhr, Citation2021; Patokorpi, Citation2006), and the gig economy. Publications in the red cluster also studied digital nomads from the perspective of the recent pandemic. For example, de Almeida et al. (Citation2021) see COVID-19 as an opportunity to test digital nomadism, while Richards and Morrill (Citation2021) see COVID-19 as a challenge for young travellers and the travel business.

Publications from the green cluster deal with nomadic lifestyles based on work and location independence. This small cluster includes, for example, the Reichenberger (Citation2018) study, which examined the motivations and lifestyles of digital nomads, and the Mancinelli (Citation2020) study which, based on ethnographic and non-ethnographic research, describes the cases of digital nomads from Chiang Mai.

The blue cluster, which refers to the differences between digital, nomadic and remote work, consists of studies by Nash et al. (Citation2021) and Hannonen (Citation2020). Hannonen (Citation2020) argues that it is important to distinguish digital nomadism from telecommuting and remote working. In so doing, she builds on the work of Thompson (Citation2018), who clearly distinguishes between remote workers, who have a stable home, and digital nomads, who do not. Nash et al. (Citation2021) goes even further, arguing that it is misleading to label digital nomads merely as location-independent workers because the ability to find or create a suitable workspace that matches individual preferences and technical requirements is critical for digital nomads.

Evolution of core concepts in digital nomad research

We analysed the authors’ keywords to capture the evolution of core concepts in digital nomad research. Mobile technologies have become one of the most critical factors for developing digital nomads. Patokorpi (Citation2006) studied how mobile technologies and ICT can be embedded in the education of future digital nomads. Between 2013 and 2018, researchers addressed topics related to the Internet. As Demaj et al. (Citation2021) wrote, a mobile device and an internet connection are most important for digital nomads. Bozzi (Citation2020) even calls digital nomads “Internet-enabled remote workers”. Similarly, Lee et al. (Citation2019) interviewed digital nomads and found that high-speed internet is a priority when choosing a workspace. Our research results thus support these claims and highlight the Internet’s importance in the lives of digital nomads.

The perception of digital nomads as a mobile people, that is, individuals with a migration lifestyle, is supported by many studies (Hannonen, Citation2020; Müller, Citation2016; Nash et al., Citation2018; Reichenberger, Citation2018). As mentioned above, moving from place to place is one of the basic ideas of nomadism. As our results reveal, the migratory lifestyle, referred to as mobility or location independence, is a core concept that permeates research on digital nomads through years of study – the themes emerged in 2018, 2019, and 2020. The combination of work and tourism is another fundamental principle of digital nomadism. A lifestyle that combines work and travel is what makes digital nomads their true selves. The ideal work/leisure ratio is exactly what nomads are looking for (Orel, Citation2019). Nash et al. (Citation2018) point out that global travel adventure is one of the critical elements of digital nomads. Our results build on these claims and confirm that work and tourism are core concepts of digital nomadism.

In 2018, the core concept was youth travel. Reichenberger (Citation2018) states that digital nomads are mainly young people (Millennials or Generation Z). Also, Seliverstova et al. (Citation2017) mentions that these generations have been crowded by modern technologies from birth and, therefore, find it much more natural to work with them. In accordance with current knowledge, our results confirm that the gig economy is another core concept of digital nomadism. Some scholars describe digital nomadism as a form of flexible working in the gig economy (Jarrahi et al., Citation2019; Nash et al., Citation2018; Thompson, Citation2018). Cook (Citation2020) points out that a large portion of autonomy and self-determination is needed in the gig economy to allow people to maintain the discipline of digital nomads.

The definition and conceptualization of digital nomads is a topic that has been a subject of several studies – as the blue cluster from the analysis confirms. As we stated in the literature review, there are many definitions of terms such as nomadic work, remote work or digital work (e.g. Bozzi, Citation2020; Hannonen, Citation2020; Hensellek & Puchala, Citation2021; Müller, Citation2016; Nash et al., Citation2018; Reichenberger, Citation2018). However, the phenomenon of digital nomadism is as of yet not firmly established (Reichenberger, Citation2018), nor is it a well-established area of research (Hannonen, Citation2020).

COVID-19 changed the world as we knew it. Almost the entire world had to move into a virtual workspace in a matter of weeks. Most companies chose to work remotely due to concern about the spreading virus (Abarca et al., Citation2020). Employees had to get used to new ways of working and use ICT technology to communicate and work daily (Frost & Duan, Citation2020; Newman & Ford, Citation2020). As our research shows, researchers have explored the impact of COVID-19 on digital nomads. COVID-19 raised interest in experiencing digital nomadism (de Almeida et al., Citation2021). COVID-19 has also changed the way people meet. As Milosevic et al. (Citation2021) pointed out, in the post-COVID-19 era business conferences and similar meetings have been moved online, which may save money for the companies and time for the employees (Thompson, Citation2018). But as Richards and Morrill (Citation2021) point out, COVID-19 also affected the tourism sector, resulting in, among other things, reduced travel possibilities for digital nomads.

In addition to COVID-19, co-working is also an important topic. Co-working centres are, to some extent, a substitute for open office space. Co-working centres are popular workplaces for digital nomads, as they offer the necessary infrastructure that nomads need. The motivation for choosing co-working centres may be the need for a pleasant and well-equipped workspace, a separation of work and personal life (or environment), and the need for socialization and professional collaboration (Lee et al., Citation2019). According to Orel (Citation2019), co-working centres can be viewed from three perspectives: a community centre, an optimizing work-flow environment, and a supportive space that encourages individuals to pursue job opportunities. Consistent with the literature (Chevtaeva & Denizci-Guillet, Citation2021; Cruz et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2019; Orel, Citation2019, Citation2021), this research finds that co-working is a core theme for digital nomadism.

Conclusion

The present research aims to explore research on digital nomadism. This paper uncovers the underlying concepts, and explores leading countries and authors, as well as their evolution over time to reveal opportunities for future research. This study is exploratory and interpretive – in it we used bibliometrics, we systematically searched all articles indexed in the WOS database. This research also provides directions for a future conceptualization of digital nomadism.

In this research, we understand digital nomads as individuals with a mobile lifestyle that combines work and leisure and requires a particular set of skills and equipment. This study followed the evolution of scholarly production in the WOS database, identifying key authors and countries that have the potential to become pioneers in the field of digital nomads. It also identified 17 core concepts of digital nomad research (COVID-19, co-working, digital work, gig economy, internet, lifestyle, lifestyle migration, location independence, mobile technology, mobility, networks, nomadic work, remote work, tourism, work, work practices, youth travel). Furthermore, our findings suggest that there are three areas of research into digital nomadism in general. The first of these are publications focusing on the definition and distinction between remote, nomadic, and digital work. The second are publications on nomadic lifestyles and location independence. And the third are publications that address the factors that define and affect the lives of digital nomads. Taken together, these 17 core concepts and 3 areas of research form a framework for research on digital nomadism. Based on our results, it is possible to identify themes that have not yet been addressed in formal research and need to be addressed in the future. The area of policymaking and legislative changes that would make life more settled for digital nomads has not been identified as a core theme. Furthermore, economic and taxation factors of nomadic life have not received significant scholarly discussion. Last but not least, we perceive a lack of development in social media research – digital nomads often use social media to share their nomadic lifestyle. Further work needs to be done to determine how the 17 core concepts identified in this study affect the lives of digital nomads (e.g. empirical research or meta-analysis of the factors we have identified in this paper). Moreover, a study of the changes in working style wrought by COVID-19 pandemic is yet to be defined. Furthermore, a bibliometric study that would analyse data from other scientific databases (such as Scopus, Google Scholar, Pubmed, etc.) is needed to complete the picture of scientific publishing in digital nomadism.

One limitation of the study is the scarcity of elements of bibliometric analysis. For example, we only used articles indexed in one database WOS, thus limiting the number of publications, authors and themes we identified in this study. Therefore, further bibliometric analysis of publications in other databases is needed to extend the results of our investigation. Another limitation comes from the use of author keywords to analyse core themes. Further limitation is the deletion of publications that were not written in English (see the screening process in the Materials and Methods section). Deleting non-English written articles may have biased the results of our analysis of national contributions to the study of digital nomadism. Despite its limitations, the study certainly adds to our understanding of research into the phenomenon of digital nomads.

The findings reported here shed new light on research into digital nomadism. The study contributes to our understanding of core concepts of digital nomads. It is beneficial not only for researchers who want to understand the topic of digital nomadism but also for policymakers who are preparing changes in labour or tax law, employers who are managing digital nomads and co-working space companies, etc.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abarca, V. M. G., Palos-Sanchez, P. R., & Rus-Arias, E. (2020). Working in virtual teams: A systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. IEEE Access, 8, 168923–168940. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3023546

- Aldag, R., & Kuzuhara, L. (2015). Creating high performance teams. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203109380

- Alekseevna, B., Efimovna, K., & Valerievna, R. (2019). Digital information technologies and navigation systems in the development of youth sports tourism (on the example of the Tyumen and Chelyabinsk regions) (V. Erlikh & S. Smolina, Eds.; WOS:000625435700005; Vol. 17, pp. 17–19). https://doi.org/10.2991/icistis-19.2019.5

- Al-Hadi, N., & Al-Aufi, A. (2019). Information context and socio-technical practice of digital nomads. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 68(4–5), 431–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-10-2018-0082

- Al-Zobaidi, S. (2009). Digital nomads: Between homepages and homelands. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 2(2), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1163/187398509X12476683126707

- Andrejuk, K. (2022). Pandemic transformations in migrant spaces: Migrant entrepreneurship between super-digitalization and the new precarity. Population, Space and Place, 28(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2564.

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Aria, M., Misuraca, M., & Spano, M. (2020). Mapping the evolution of social research and data science on 30 years of social indicators research. Social Indicators Research, 149(3), 803–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02281-3

- Aroles, J., Granter, E., & de Vaujany, F. (2020). ‘Becoming mainstream’: The professionalisation and corporatisation of digital nomadism. New Technology, Work and Employment, 35(1), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12158

- Bjørn, P., & Ngwenyama, O. (2009). Virtual team collaboration: Building shared meaning, resolving breakdowns and creating translucence. Information Systems Journal, 19(3), 227–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2007.00281.x

- Bozzi, N. (2020). #Digitalnomads, #solotravellers, #remoteworkers: A cultural critique of the traveling entrepreneur on Instagram. Social Media + Society, 6(2) . https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120926644.

- Chevtaeva, E., & Denizci-Guillet, B. (2021). Digital nomads’ lifestyles and coworkation. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100633

- Cnossen, B., de Vaujany, F., & Haefliger, S. (2021). The street and organization studies. Organization Studies, 42(8), 1337–1349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620918380

- Cook, D. (2020). The freedom trap: Digital nomads and the use of disciplining practices to manage work/leisure boundaries. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 355–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00172-4

- Cruz, R., Franqueira, T., & Pombo, F. (2021). Furniture as feature in co-working spaces. Spots in Porto city as case study. Res Mobilis-International Research Journal of Furniture and Decorative Objects, 10(13), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.17811/rm.10.13-3.2021.316-338

- Cuccurullo, C., Aria, M., & Sarto, F. (2016). Foundations and trends in performance management. A twenty-five years bibliometric analysis in business and public administration domains. Scientometrics, 108(2), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1948-8

- Dal Fiore, F., Mokhtarian, P., Salomon, I., & & Singer, M. (2014). ‘Nomads at last’? A set of perspectives on how mobile technology may affect travel. Journal of Transport Geography, 41, 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.08.014

- Davison, R. M. (2020). The transformative potential of disruptions: A viewpoint. International Journal of Information Management, 55(2), 102149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102149.

- de Almeida, M., Correia, A., Schneider, D., & de Souza, J. (2021). COVID-19 as opportunity to test digital nomad lifestyle (W. Shen, J. Barthes, J. Luo, Y. Shi, & J. Zhang, Eds.), WOS:000716858200204, pp. 1209–1214). https://doi.org/10.1109/CSCWD49262.2021.9437685

- de Loryn, B. (2022). Not necessarily a place: How mobile transnational online workers (digital nomads) construct and experience ‘home’. Global Networks, 22(1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12333

- Demaj, E., Hasimja, A., & Rahimi, A. (2021). Digital nomadism as a new flexible working approach: Making Tirana the next European hotspot for digital nomads. In M. Orel, O. Dvouletý, & V. Ratten (Eds.), The flexible workplace (pp. 231–257). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62167-4_13

- Druta, R., Druta, C., Negirla, P., & Silea, I. (2021). A review on methods and systems for remote collaboration. Applied Sciences, 11(21), 10035. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112110035

- Eisenberg, J., & Mattarelli, E. (2017). Building bridges in global virtual teams: The role of multicultural brokers in overcoming the negative effects of identity threats on knowledge sharing across subgroups. Journal of International Management, 23(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2016.11.007

- Foley, A., Moncada, S., Mycoo, M., Nunn, P., Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V., & Evans, C. (2022). Small Island Developing States in a post-pandemic world: Challenges and opportunities for climate action. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Climate Change, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.769.

- Frost, M., & Duan, S. X. (2020). Rethinking the role of technology in virtual teams in light of COVID-19. ACIS 2020 Proceedings.

- Gilson, L. L., Maynard, M. T., & Bergiel, E. B. (2013). Virtual team effectiveness: An experiential activity. Small Group Research, 44(4), 412–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496413488216

- Green, P. (2020). Disruptions of self, place and mobility: Digital nomads in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Mobilities, 15(3), 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2020.1723253

- Hall, G., Sigala, M., Rentschler, R., & Boyle, S. (2019). Motivations, mobility and work practices; The conceptual realities of digital nomads (J. Pesonen & J. Neidhardt, Eds.; WOS:000518026800034; pp. 437–449). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05940-8_34

- Hannonen, O. (2020). In search of a digital nomad: Defining the phenomenon. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00177-z

- Hensellek, S., & Puchala, N. (2021). The emergence of the digital nomad: A review and analysis of the opportunities and risks of digital nomadism. In M. Orel, O. Dvouletý, & V. Ratten (Eds.), The flexible workplace (pp. 195–214). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62167-4_11

- Jarrahi, M., Philips, G., Sutherland, W., Sawyer, S., & Erickson, I. (2019). Personalization of knowledge, personal knowledge ecology, and digital nomadism. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(4), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24134

- Jawadi, N. (2013). E-leadership and trust management: Exploring the moderating effects of team virtuality. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction, 9(3), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.4018/jthi.2013070102

- Jung, P., & Buhr, F. (2021). Channelling mobilities: Migrant-owned businesses as mobility infrastructures. Mobilities, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1958250.

- Kathleen, S., Sven, S., Claudia, N. B., & Frank, E. (2021). Fulfilling remote collaboration needs for new work. Procedia Computer Science, 191, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.07.021

- Klyagin, S., Volobuev, A., Zamaraeva, E., Borovinskikh, O., & Kuzina, E. (2018). On non-classic ontological models for studying digital nomadism phenomena. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 8(10), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.26655/mjltm.2018.10.1

- Korjus, K., del Castillo, C., & Kotka, T. (2017). Perspectives for e-residency strengths, opportunities, weaknesses and threats (L. Teran & A. Meier, Eds.; WOS:000464415600029; pp. 177–181).

- Korpela, M. (2020). Searching for a countercultural life abroad: Neo-nomadism, lifestyle mobility or Bohemian lifestyle migration? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(15), 3352–3369. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1569505

- Lee, A., Toombs, A., Erickson, I., & Assoc Comp Machinery. (2019). Infrastructure vs. community: Co-spaces confront digital nomads’ paradoxical needs (WOS:000482042102119). Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3313064

- Leydesdorff, L., Wagner, C. S., Park, H.-W., & Adams, J. (2013). Colaboración internacional en ciencia: Mapa global y red. Profesional de La Información, 22(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2013.ene.12

- Macgilchrist, F., Allert, H., & Bruch, A. (2020). Students and society in the 2020s. Three future ‘histories’ of education and technology. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1656235

- MacRae, G. (2016). Community and cosmopolitanism in the new Ubud. Annals of Tourism Research, 59, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.03.005

- Makimoto, T., & Manners, D. (1997). Digital nomad. Wiley.

- Mancinelli, F. (2020). Digital nomads: Freedom, responsibility and the neoliberal order. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00174-2

- Marques, B., Teixeira, A., Silva, S., Alves, J., Dias, P., & Santos, B. S. (2021). A critical analysis on remote collaboration mediated by Augmented Reality: Making a case for improved characterization and evaluation of the collaborative process. Computers & Graphics, 102, 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2021.08.006.

- McElroy, E. (2020). Digital nomads in siliconising Cluj: Material and allegorical double dispossession. Urban Studies, 57(15), 3078–3094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019847448

- Meluso, J., Johnson, S., & Bagrow, J. (2020). Making virtual teams work: Redesigning virtual collaboration for the future [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wehsk

- Milosevic, P., Milosevic, V., & Milosevic, G. (2021). Office buildings throughout centuries vs now, in the 21st century – Developing innovative space concepts. Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment, 14(2), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.21307/acee-2021-013

- Mladenovic, D. (2016). Concept of ‘figure of merit’ for place marketing in digital nomadism ages (D. Petranova, L. Cabyova, & Z. Bezakova, Eds.; WOS:000405153400039; pp. 393–403).

- Müller, A. (2016). The digital nomad: Buzzword or research category? Transnational Social Review, 6(3), 344–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/21931674.2016.1229930

- Nash, C., Jarrahi, M., & Sutherland, W. (2021). Nomadic work and location independence: The role of space in shaping the work of digital nomads. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(2), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.234

- Nash, C., Jarrahi, M., Sutherland, W., & Phillips, G. (2018). Digital nomads beyond the buzzword: Defining digital nomadic work and use of digital technologies (G. Chowdhury, J. McLeod, V. Gillet, & P. Willett, Eds.; WOS:000449872000025; Vol. 10766, pp. 207–217). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78105-1_25

- Naz, A., Kopper, R., McMahan, R., Nadin, M., Rosenberg, E., Krum, D., Wartell, Z., Mohler, B., Babu, S., Steinicke, F., & Interrante, V. (2017). Emotional qualities of VR space (WOS:000403149400003, pp. 3–11). https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2017.7892225

- Newman, S. A., & Ford, R. C. (2020). Five steps to leading your team in the virtual COVID-19 workplace. Organizational Dynamics, 50(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100802.

- Nikolaeva, E., & Kotliar, P. (2019). Attributive properties of a media user in the context of network communications. IIOAB Journal, 10(Suppl. 1), 45–48.

- Nurhas, I., Aditya, B., Jacob, D., & Pawlowski, J. (2021). Understanding the challenges of rapid digital transformation: The case of COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Behaviour & Information Technology, 46(9), 1290–1303. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2021.1962977.

- Orel, M. (2019). Co-working environments and digital nomadism: Balancing work and leisure whilst on the move. World Leisure Journal, 61(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2019.1639275

- Orel, M. (2021). Life is better in flip flops. Digital nomads and their transformational travels to Thailand. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 15(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-12-2019-0229

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Patokorpi, E. (2006). Abductive reasoning and ICT enhanced learning: Towards the epistemology of digital nomads (C. Zielinski, P. Duquenoy, & K. Kimppa, Eds.; WOS:000235187200007; Vol. 195, pp. 101–117). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-31168-8_7

- Philippou, M. (2013). Neo-nomad: The man of the networks revolution era (J. Botia & D. Charitos, Eds.; WOS:000360240400081; Vol. 17, pp. 709–721). https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-286-8-709

- Powell, A., Piccoli, G., & Ives, B. (2004). Virtual teams: A review of current literature and directions for future research. SIGMIS Database, 35(1), 6–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/968464.968467

- Reichenberger, I. (2018). Digital nomads – A quest for holistic freedom in work and leisure. Annals of Leisure Research, 21(3), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2017.1358098

- Richards, G. (2015). The new global nomads: Youth travel in a globalizing world. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(3), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2015.1075724

- Richards, G., & Morrill, W. (2021). The challenge of Covid-19 for youth travel. Anais Brasileiros De Estudos Turisticos-Abet, 11, 1–8.

- Seliverstova, N., Iakovleva, E., & Grigoryeva, O. (2017). Human behavior in digital economy: The main trends (A. Karpov & Martyushev, Eds.; WOS:000416099600098; Vol. 38, pp. 600–605).

- Shehatta, I., & Al-Rubaish, A. M. (2019). Impact of country self-citations on bibliometric indicators and ranking of most productive countries. Scientometrics, 120(2), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03139-3

- Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2021). The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 126(6), 5113–5142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03948-5

- Thompson, B. Y. (2018). Digital nomads: Employment in the online gig economy. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation, 1. https://doi.org/10.12893/gjcpi.2018.1.11

- Thompson, B. Y. (2019). The digital nomad lifestyle: (Remote) work/leisure balance, privilege, and constructed community. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 2(1–2), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-018-00030-y

- Tyutyuryukov, V., & Guseva, N. (2021). From remote work to digital nomads: Tax issues and tax opportunities of digital lifestyle (WOS:000718365000036). IFAC-PapersOnLine, 54(13), 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2021.10.443

- von Zumbusch, J., & Lalicic, L. (2020). The role of co-living spaces in digital nomads’ well-being. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00182-2

- Willment, N. (2020). The travel blogger as digital nomad: (Re-)imagining workplace performances of digital nomadism within travel blogging work. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 391–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00173-3

- Woldoff, R. A., & Litchfield, R. C. (2021). Digital nomads: In search of meaningful work in the new economy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190931780.001.0001

- Yang, E., Bisson, C., & Sanborn, B. E. (2019). Co-working space as a third-fourth place: Changing models of a hybrid space in corporate real estate. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 21(4), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRE-12-2018-0051