ABSTRACT

Objectives: To explore real-world prognoses for tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients and the associated reasons for TKI discontinuation.

Methods: We investigated, using the medical records of 85 consecutive CML patients who received TKIs between December 2001 and August 2016 at our hospital, reasons for discontinuation, duration of TKI treatment before discontinuation, molecular response (MR) status at TKI discontinuation, treatment-free remission (TFR) duration, and overall survival after TKI discontinuation.

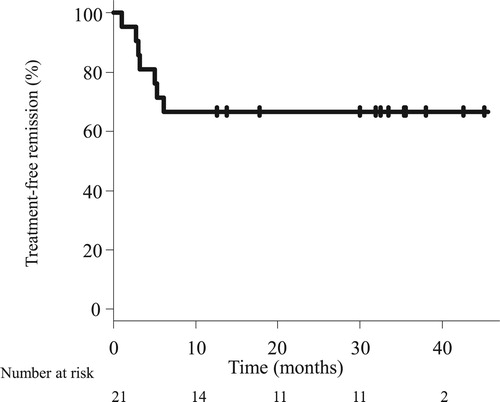

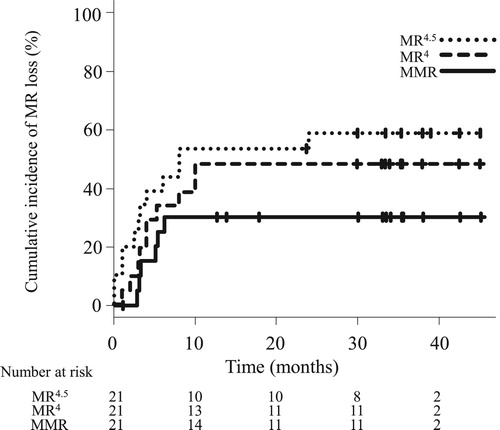

Results: TKI therapy was discontinued in 21 patients. The median treatment duration before discontinuation was 68.3 months. The response statuses at discontinuation were MR4 (n = 2), MR4.5 (n = 4), and ≥MR5 (n = 15). The reasons were pleural effusion (n = 5); requests for prolonged deep molecular response (DMR) (n = 4); ischemic heart disease, anemia, and economic problems (each, n = 3); renal dysfunction (n = 2); and hyperkalemia, diarrhea, dementia, asthma, and desire to get pregnant, (each, n = 1). All patients were alive with median follow-up period of 32.1 months. TFR was maintained in 14 patients, and the 2-year TFR proportion was 66.7%. Seven patients restarted TKI therapy and achieved MR4 within median of 3 months. The duration of TKI administration before discontinuation (≥ 70 months) was favored longer TFR durations.

Conclusion: TKI was safely discontinued in clinical practice and yielded TFR rates similar to those observed in previous clinical trials, regardless of reason. Achievement of TFR significantly impacts patients’ quality of life and should be considered in clinical practice.

Introduction

Since the introduction of BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in clinical practice, the prognoses of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) have dramatically improved. Second-generation TKIs, nilotinib and dasatinib are thought to be better treatment options than imatinib in upfront settings [Citation1]. However, long TKI therapy durations are associated with the development of adverse events such as peripheral artery stenosis, ischemic heart disease, pulmonary effusion, and pulmonary hypertension [Citation2,Citation3]. Moreover, TKI therapy is expensive, and it was previously believed that life-long treatment with oral TKIs was needed, because CML stem cells are not eradicated by TKIs [Citation4]. However, the possibility of discontinuing TKI in the treatment of CML has emerged after several clinical trials showed that approximately half of all patients in whom deep molecular response (DMR) was achieved were able to discontinue TKI therapy [Citation5–10]. However, the consideration of TKI discontinuation in patients with complications, intolerance, or other problems in real-world settings is a challenge. Therefore, in this study, to compare clinical trial results with real-world practice data, we retrospectively investigated the outcomes of patients who had to discontinue TKI therapy due to these problems.

Material and methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Research participants and study design

We reviewed the medical records of patients who were diagnosed with CML and received TKI therapy between December 2001 and August 2016 in Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital consecutively. Cases, defined as two consecutive samples with DMR ≥ 4 weeks apart and in whom TKI therapy was discontinued, were identified from medical records. The reason for TKI discontinuation, duration of TKI treatment before discontinuation, duration of molecular response (MR) before discontinuation, MR status at TKI cessation, and rates of treatment-free remission (TFR) were investigated.

Measurement of BCR-ABL1 transcript

BCR-ABL1 transcript levels were measured using a commercial Amp-CML kit (Fujirebio Inc, Japan) [Citation11] till March 2015, and Major BCR-ABL1 mRNA assay kit (Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Japan) [Citation12] thereafter. The lowest positive values in the Amp-CML kit and Major BCR-ABL1 mRNA assay kit are 0.005% and 0.0007% BCR-ABL1 (International Scale, BCR-ABL1IS), respectively.

Definition

The Sokal risk score was determined as previously reported [Citation13]. MR classification was based on the BCR-ABL1/control ABL1 gene transcript ratio, as expressed in the IS [Citation14], in which a major molecular response (MMR) is defined as ≤0.1% BCR-ABL1IS, MR4 as ≤0.01% BCR-ABL1IS, MR4.5 as ≤0.0032% BCR-ABL1IS, and MR5 as ≤0.001% BCR-ABL1IS. DMR was defined in samples with a value ≤ 0.01% BCR-ABL1IS. Molecular relapse (i.e. loss of MMR), and loss of MR4 and MR4.5 were defined as single samples with values >0.1%, and >0.01% and >0.0032% BCR-ABL1IS, respectively. TFR was defined as the duration from the date of TKI cessation to the TKI recommencement date, and was censored if TKI therapy was not restarted.

Statistical analysis

The TFR rates and cumulative incidences of MR loss were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analyses [Citation15]. The sustained MMR rates were compared between the two groups using a log rank test, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR computer software [Citation16].

Result

Patient characteristics

Eighty-five CML patients were treated with TKIs during the study period. Of these, 21 (24.7%) achieved DMR and TKI therapy was discontinued. Their characteristics are summarized in . The median age at TKI therapy discontinuation was 69 years (range, 40–80). The numbers of patients with a low, intermediate, and high Sokal score at diagnosis were 8, 11, and 2, respectively. The median TKI duration before discontinuation was 68.3 months (range, 21.7–161.4), and the median duration of MR4 before discontinuation was 43.8 months (range, 15.6–96.1). Two patients had received interferon treatment, while none of the patients had previously received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Table 1. Patient characteristics before TKI discontinuation.

Outcomes after TKI therapy discontinuation

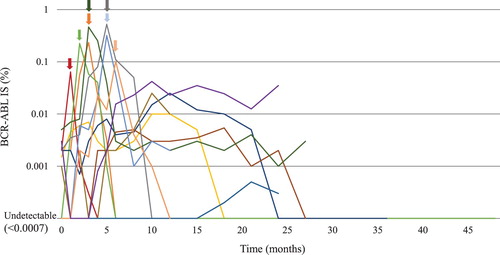

The TFR rate was estimated as 66.7% (95% CI, 42.5–82.5) at 24 months (). The cumulative incidences of MMR, MR4, and MR4.5 loss at 24 months were estimated as 30.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 14.7–54.9), 47.6% (95% CI, 29.1–70.3), and 57.7% (95% CI, 38.0–78.7), respectively (). At the time of analysis, 21 patients had completed a median of 32.1 months of follow-up after TKI therapy discontinuation (). While 7 patients required TKI retreatment, 14 had maintained MMR for a median of 34.4 months (range, 12.6–45.1). Of the 14 patients, 9 patients did not have detectable BCR-ABL1 transcript levels throughout the follow-up period. In contrast, 5 patients showed fluctuations in the BCR-ABL1 transcript levels after TKI discontinuation. One 70-year-old female patient (Sokal score low, yellow line in ) initially received imatinib. However, due to progressive anemia and the worsening of asthma, imatinib administration was stopped at MR4.5. MR4.5 was lost on assessment after a month of discontinuation. However, MR4.5 was re-achieved on assessment 4 months after discontinuation. Her BCR-ABL1 transcript levels fluctuated between 0.001% and 0.1%, and MR5 was finally achieved on assessment 18 months after discontinuation. MR5 was sustained at the time of analysis (TFR duration, 33 months). In one 72 -year-old male patient (Sokal score intermediate, purple line in ), dasatinib was discontinued at MR4.5 due to recurrent pleural effusion, hyperkalemia, and economic problems. Five months after dasatinib discontinuation, MR5 was lost and progressed to MMR. MMR was maintained at the time of analysis (TFR duration, 24 months).

Figure 2. Cumulative incidences of molecular response loss. Solid, broken and dotted lines represent loss of major molecular response (MMR), molecular response ≤ 0.01% BCR-ABLIS (MR4), and molecular response ≤ 0.0032% BCR-ABLIS (MR4.5), respectively. MR, molecular response.

Figure 3. The kinetics of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels after tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation. Seven patients lost treatment-free remission after TKI discontinuation. Each arrow represents the point of TKI recommencement. MMR, major molecular response; MR, molecular response, TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; IS, International Scale.

Table 2. Patient characteristics after TKI discontinuation.

None of the patients died or experienced progression to acute phase or blast crisis during the follow-up period.

TKI retreatment after MMR loss

Seven patients in whom TKI therapy was discontinued resumed treatment after a median of 5.0 months due to molecular relapse (, ). All patients with molecular relapse achieved DMR within a median of 3 months after TKI therapy was restarted. A 38-year-old female patient (Sokal score low, red line in ) attempted to get pregnant and TKI therapy was discontinued at MR4 after 37.2 months of imatinib treatment. On the first visit 1 month later, the peripheral blood BCR-ABL1 transcript levels had increased and MR4 was lost. Although MMR was still maintained, the patient desired to restart imatinib and underwent treatment again. In a 54-year-old female patient (Sokal score low, orange line in ), dasatinib was discontinued at MR4.5 due to recurrent pleural effusion; 2.8 months after TKI therapy discontinuation, MMR was lost and bosutinib was restarted. However, 2.1 years after bosutinib administration, she discontinued bosutinib, due to recurrent diarrhea, and had undetectable BCR-ABL1 transcript levels. After bosutinib discontinuation, at the time of the analysis, she had maintained undetectable BCR-ABL1 transcript levels for 19 months.

TKI withdrawal syndrome

Four patients (19.0%) experienced TKI withdrawal syndrome 1–3 months after TKI discontinuation. Three of 4 patients complained of grade 1 muscle pain of the extremities, according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 4.0 [Citation17]. One patient experienced grade 2 pain of the shoulder and upper extremities and received acetaminophen. None of the laboratory data were changed during observation, and all patients recovered completely within 5 months.

Reasons for TKI discontinuation

The reasons for discontinuation were recurrent pleural effusion (5 patients), progression of ischemic heart disease (3), anemia (3), chronic kidney disease (2), hyperkalemia (1), diarrhea (1), dementia (1), asthma (1), patients request after prolonged DMR (4), economic problems (3), and planned pregnancy (1) ().

Table 3. Reasons for TKI discontinuation.

Factors affecting sustained MMR after TKI discontinuation

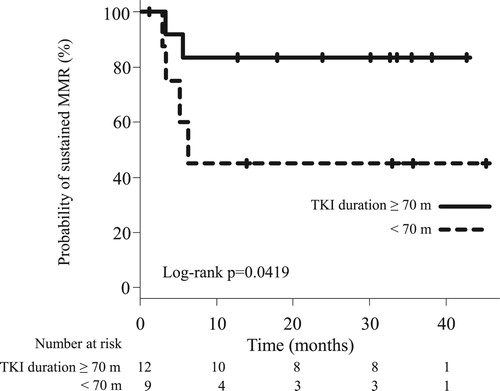

In the univariate analysis, patients’ age (<70 vs ≥70 years), sex, Sokal risk score, time to MR4 before TKI discontinuation (<30 vs ≥30 months), MR at TKI discontinuation (<MR5 vs ≥MR5), duration of TKI administration before TKI discontinuation (< 70 vs ≥70 months), duration of MR4 before TKI discontinuation (<40 vs ≥40 months), and type of TKI before TKI discontinuation (imatinib vs second generation TKIs) were investigated (). The result showed that the duration of TKI administration before TKI discontinuation was a significant factor influencing sustained MMR (p = 0.0419, ).

Figure 4. Sustained MMR according to the duration of TKI administration before tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation. Solid and dotted lines represent the duration of TKI administration ≥70 and <70 months, respectively. MMR, major molecular response; MR, molecular response, TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table 4. Univariate analysis of factors for sustained MMR.

Discussion

In the present study, we retrospectively investigated the outcomes of patients with TKI discontinuation due to complications or TKI-related adverse events in daily clinical practice. Our study showed that in 14 of 21 patients (66.7%) TFR could be maintained at the time of analysis with a median period of 32.1 months. To the best of our knowledge, our study includes the longest follow-up period after TKI discontinuation among all real-world unplanned TKI discontinuation studies [Citation18–20]. The initial TKI was determined based on the patients’ and primary physicians’ choices. In Japan, imatinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib are approved for treatment of newly diagnosed CML patients. However, because Japanese patients prefer tablets, and taking medication between meals twice a day is inconvenient, most patients and physicians chose imatinib or dasatinib.

Although 7 of 21 patients experienced molecular relapse, and were retreated with TKIs, 1 of the 7 experienced second TFR; therefore, a total of 15 out of 21 patients (71.4%) had sustained TFR at the time of the analysis. In previous studies, two patients each experienced progression to the accelerated phase [Citation18] and lymphoid blast crisis [Citation10] after TKI discontinuation. However, in the present study, none of the patients died or experienced progression to the accelerated phase or blast crisis during follow-up. These data indicate that even in real-world settings, some patients who achieve DMR may stop TKI therapy, regardless of the reason for TKI discontinuation.

Previously reported clinical predictive factors for TFR include the duration of TKI therapy [Citation21,Citation22], duration of DMR prior to discontinuation [Citation22], interferon administration prior to TKI [Citation9], Sokal risk score at diagnosis [Citation21], undetectable molecular residual disease at TKI cessation [Citation7], and time taken to achieve DMR after TKI initiation [Citation9]. This study also demonstrated the significance of the duration of TKI administration before TKI discontinuation. While DMR duration before TKI discontinuation was not significant, it tended to have an effect on TFR. Although strong predictive factors have not yet been established in such cases, it is indicated that cases with a longer TFR duration may require a deeper and longer DMR before TKI discontinuation. There is a need for further studies to further elucidate the predictive factors associated with sustained TFR.

In this study, 6 patients restarted TKI due to MMR loss (). Although the optimal MR threshold for the triggering of the restart of TKI therapy is unclear, as many previous studies used MMR loss as a practical trigger [Citation7–10,Citation22], we used it to restart TKI in most of the patients except one. In all the patients requiring TKI retreatment, therapy was restarted within 6 months after TKI discontinuation, and all of them achieved the MR status observed before TKI discontinuation within 5 months. One of these 6 patients attempted second TKI discontinuation, and this patient had maintained TFR for 19 months at the time of analysis. Second TFR has been found to be achieved in 30–50% of patients [Citation23]. However, a previous study demonstrated late molecular relapse after second TKI discontinuation [Citation23]; therefore, careful attention should be given to follow-up patients.

Among 14 TFR patients, fluctuating BCR-ABL1 transcript levels below 0.1% BCR-ABLIS without TKI treatment was observed in 6 (42.8%, ). Patients with BCR-ABL1 fluctuations between 0.01% and 0.1% BCR-ABLIS (, purple line) should be considered with caution for late molecular recurrence in the follow-up. Previous TFR studies have also reported on patients with BCR-ABL1 fluctuations. Recently, several studies have revealed the functional defects of natural killer (NK) cells in patients with untreated CML, and the role of mature NK cells in TFR maintenance [Citation24,Citation25] after TKI discontinuation. When TFR is achieved or BCR-ABL1 fluctuates to low levels in patients with CML patients, the immune system including NK cells is speculated to contribute to the control of the remaining CML cells in the equilibrium phase. Further investigations of this immunological phenomenon may aid in the development of TKI discontinuation procedures and improvements in the TFR proportion.

Regarding the reasons for TKI discontinuation, previous retrospective studies on unplanned TKI discontinuation reported that (1) adverse events (pleural effusion, muscle pain, malignancy, and liver dysfunction), (2) economic problems, (3) patients’ request, and (4) pregnancy were the main issues [Citation18–20]. In this study, adverse events and economic problems were common reasons for TKI discontinuation. In Japan, generic imatinib was approved in 2013. The price of the generic drug is 30% lower than that of originator imatinib. However, generic imatinib is still expensive and its use is of concern to patients. Of note, patient request was one of the most frequent reasons for discontinuation of TKI treatment. Information on TKI discontinuation trials from mass media and the internet may contribute to such requests.

Currently, many guidelines recommend that in CML patients responding optimally to treatment, the standard recommended dose should be continued [Citation26–28]; the recommendations for TKI discontinuation are slightly conservative. In addition to short-term toxicities such as fluid retention, diarrhea, myalgia, musculoskeletal pain, and rash [Citation2], long-term toxicities such as cardiopulmonary toxicities [Citation3] and secondary malignancy [Citation3] influence patients’ decisions to discontinue TKI. Furthermore, as the annual cost of TKI is approximately 50,000 US dollars per patient in Japan, it is not only a serious problem for patients but also a concern for society. These data indicate that the achievement of TFR has a greater impact on patients’ quality of life in terms of complications, drug adverse events, and economic burden than the disease itself, and should become an important consideration in clinical practice.

In conclusion, this study showed that TKI discontinuation in clinical practice yielded TFR rates and predictive factors that were similar to those observed in previous clinical trials, regardless of the reason for TKI discontinuation, both in clinical trials and real-world settings. However, although our study showed comparable TFR proportions in real-world practice with the longest follow-up period compared in relation to other retrospective practical studies, real-world data are still growing, and studies on large series should be performed to accumulate more mature data in daily practice.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the patients participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Masaki Iino http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3471-0890

References

- Yun S, Vincelette ND, Segar JM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors versus imatinib in the first-line treatment of chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia across risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis of eight randomized trials. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16(6):e85–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.03.003

- Gora-Tybor J, Medras E, Calbecka M, et al. Real-life comparison of severe vascular events and other non-hematological complications in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia undergoing second-line nilotinib or dasatinib treatment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(8):2309–2314. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.994205

- Douxfils J, Haguet H, Mullier F, et al. Association between BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia and cardiovascular events, major molecular response, and overall survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):625–632. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5932

- Michor F, Hughes TP, Iwasa Y, et al. Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2005;435:1267–1270. doi: 10.1038/nature03669

- Mahon F-X, Réa D, Guilhot J, et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70233-3

- Imagawa J, Tanaka H, Okada M, et al. Discontinuation of dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained deep molecular response for longer than 1 year (DADI trial): a multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2(12):e528–e535. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00196-9

- Takahashi N, Tauchi T, Kitamura K, et al. Deeper molecular response is a predictive factor for treatment-free remission after imatinib discontinuation in patients with chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: the JALSG-STIM213 study. Int J Hematol. 2018;107(2):185–193. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2334-x

- Rea D, Nicolini FE, Tulliez M, et al. Discontinuation of dasatinib or nilotinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: interim analysis of the STOP 2G-TKI study. Blood. 2017;129(7):846–854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-742205

- Ross DM, Branford S, Seymour JF, et al. Safety and efficacy of imatinib cessation for CML patients with stable undetectable minimal residual disease: results from the TWISTER study. Blood. 2013;122(4):515–522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-483750

- Rousselot P, Charbonnier A, Cony-Makhoul P, et al. Loss of major molecular response as a trigger for restarting tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in patients with chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia who have stopped imatinib after durable undetectable disease. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):424–430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5797

- Yagasaki F, Niwa T, Abe A, et al. Correlation of quantification of major bcr-abl mRNA between TMA (transcription mediated amplification) method and real-time quantitative PCR. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2009;50(6):481–487.

- Nakamae H, Yoshida C, Miyata Y, et al. A new diagnostic kit, ODK-1201, for the quantitation of low major BCR-ABL mRNA level in chronic myeloid leukemia: Correlation of quantitation with major BCR-ABL mRNA kits. Int J Hematol. 2015;102(3):304–311. doi: 10.1007/s12185-015-1826-9

- Sokal JE, Cox EB, Baccarani M, et al. Prognostic discrimination in “good-risk” chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1984;63(4):789–799. doi: 10.1182/blood.V63.4.789.789

- Cross NCP, White HE, Colomer D, et al. Laboratory recommendations for scoring deep molecular responses following treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29(5):999–1003. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.29

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. doi:10.2307/2281868 doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452

- Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244

- Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

- Benjamini O, Kantarjian H, Rios MB, et al. Patient-driven discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: single institution experience. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(12):2879–2886. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.831092

- Senoo Y, Yoshioka K, Kaito S, et al. Retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes of the patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who stopped administration of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a single institution experience. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2016;57(12):2481–2489.

- Tsutsumi Y, Ito S, Ohigashi H, et al. Unplanned discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4(1):89–92. doi: 10.3892/mco.2015.653

- Etienne G, Guilhot J, Rea D, et al. Long-term follow-up of the French Stop Imatinib (STIM1) study in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(3):298–305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2914

- Saussele S, Richter J, Guilhot J, et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): a prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):747–757. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30192-X

- Legros L, Nicolini FE, Etienne G, et al. Second tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation attempt in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2017;123(22):4403–4410. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30885

- Ilander M, Olsson-Strömberg U, Schlums H, et al. Increased proportion of mature NK cells is associated with successful imatinib discontinuation in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2017;31(5):1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.360

- Chen CIU, Koschmieder S, Kerstiens L, et al. NK cells are dysfunctional in human chronic myelogenous leukemia before and on imatinib treatment and in BCR-ABL-positive mice. Leukemia. 2012;26(3):465–474. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.239

- Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al. European leukemia net recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122(6):872–884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569

- Rea D, Ame S, Berger M, et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations for clinical practice from the French chronic myeloid leukemia study group. Cancer. 2018;124(14):2956–2963. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31411

- NCCN. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Chronic Myeloid Leukemia; Version 1.2019-August 1, 2018.