ABSTRACT

Objectives

To analyze the clinical characteristics and prognosis of primary extranodal classical Hodgkin lymphoma (PE-cHL).

Methods

Clinical features and outcomes of 22 PE-cHL patients who received initial chemotherapy January 2008 to January 2018 were analyzed retrospectively, and compared with 274 primary nodal Hodgkin lymphoma (PN-cHL) patients treated in the same period.

Results

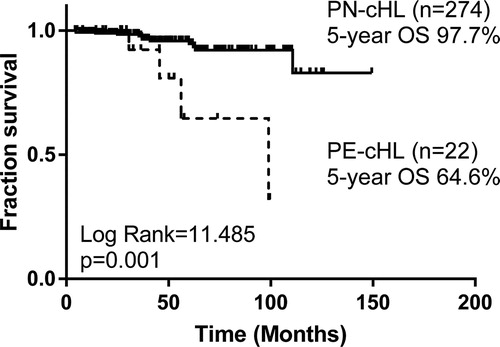

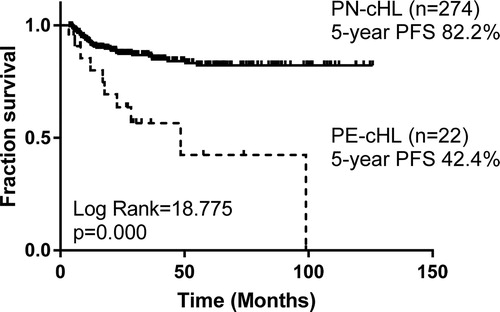

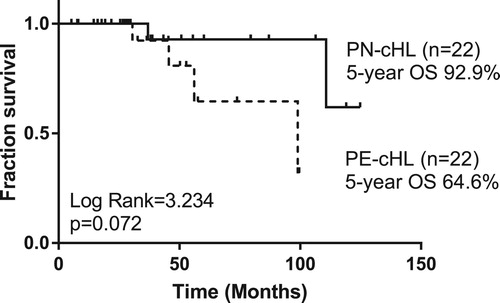

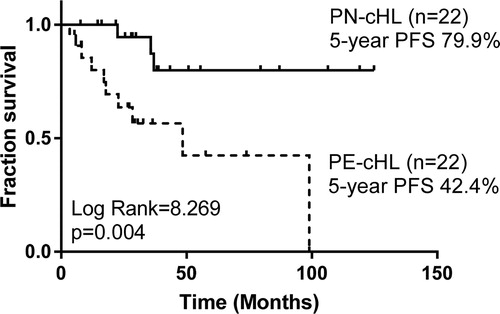

With a median follow-up period of 42 months, compared with 274 PN-cHL patients, no significant difference of overall response rate (ORR) or complete remission (CR) rate was found, but the PE-cHL patients showed a higher recurrence rate (36.4% vs. 13.1%, p = .003) and poorer survival [(5-year overall survival (OS) rate: 64.6% vs. 97.7%, p = .001; 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate: 42.4% vs. 82.2%, p < .001)]. To minimize the effects of confounding factors, PE-cHL patients were matched with PN-cHL patients at a ratio of 1:1 according to age, gender, histological types and stage. Compared with 22 matched PN-cHL cases, PE-cHL was still associated with poor PFS (5-year PFS: 42.4% vs. 79.9%, p = .004). As to 22 PE-cHL patients, univariate analysis showed elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and elevated platelet (PLT) were associated with poor PFS (p < .05).

Discussion

Compared with PN-cHLs, PE-cHLs showed a considerable shorter duration of remission, higher recurrence tendency and poorer survival, indicating that more intensive therapy may be needed.

Conclusion

The prognosis of PE-cHL is unfavorable. Elevated LDH and PLT are poor prognostic factors for PE-cHL.

Introduction

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a sort of malignancy originating from B-cell abnormal clonal expansion. The presence of Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells and abundant reactive cells in the tumor microenvironment are considered as the pathological characteristics of HL. According to the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid neoplasms [Citation1], HL is subclassified into classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) and nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL (NLPHL). cHL is further divided into four histological subtypes, including nodular sclerosis (NS), mixed cellularity (MC), lymphocyte-predominant (LP) and lymphocyte-depletion (LD). As one of the most frequent lymphoma subtype in the world, especially in children and young adults in the Western world, HL represent 15–25% of all lymphoma [Citation2]. Generally, the lesions of cHL originate from organs and structures belonging to lymphoid system with favorable prognosis. However, cHL developing from extranodal organs may also occur in some cases. Previous reports of primary extranodal cHL (PE-cHL) are rare and mostly are case analysis, and thus little is known about this special population. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective study to analyze clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of PE-cHL.

Materials and methods

Patients

From January 2008 to January 2018, 22 PE-cHL patients were admitted to the Lymphoma Department of Peking University Cancer Hospital and received initial chemotherapy. All these patients were pathologically diagnosed or confirmed according to the classification guidelines of WHO [Citation3] by expert pathologists. PE-cHL was identified as restriction of the disease to extranodal organs, with or without regional lymph node involvement, and no distant lymph node involvement [Citation4,Citation5]. Nineteen of 22 patients received positron emission tomography (PET) scan at baseline; and 12 patients received PET scan after every two cycles of chemotherapy and at the end of therapy. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) virological tests were performed to all patients before treatment. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical characteristics, laboratory results, radiological examinations and treatment efficacy of 22 PE-cHL patients, and compared their outcomes with 274 primary nodal Hodgkin lymphoma (PN-cHL) patients with complete clinical records treated in the same period. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Efficacy assessment and follow-up

The response of treatment was assessed after every two cycles of chemotherapy. Assessment of treatment response was based on the 2014 Lugano classification [Citation6]. Overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the rate of complete response (CR) plus partial response (PR). Patients were followed up until June 2018. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to death due to any cause or latest follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to relapse/progression, death due to any cause or latest follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between clinical characteristics and response rates were analyzed with the χ2 test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Survival functions were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Prognostic factor analysis was performed by the Cox regression model. All p values were two-sided, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant. To minimize the effects of confounding factors, PE-cHL patients were matched with PN-cHL patients at a ratio of 1:1 according to age, gender, histological types and stage by propensity score matching.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Of the 22 PE-cHL patients, 12 (54.5%) were male and 10 (45.5%) were female. The median age was 30 (15−69) years. The median onset time to diagnosis was 122.5 days. The most common initial symptom was cough (n = 11, 50.0%), and then followed by back pain (n = 4, 18.2%), fever (n = 1, 4.5%) and headache (n = 1, 4.5%). Five patients had asymptomatic lesions, and the lesions were discovered by routine health examination, including the X-ray and computed tomography (CT) examination. 10 (45.5%) patients had B symptoms. The most common site of extranodal lesion was lung (n = 12, 54.5%). Primary malignancies in the bone, nasopharynx, parotid gland, brain and adrenal gland were also found in this study. The extranodal lesion site of 22 PE-cHL patients are shown in . Seven (31.8%) cases were multiple primary. At the time of diagnosis, 7 (31.8%) patients were at limited-stages (stage IE and IIE) and 15 (68.2%) patients were at advanced stages (stage IV). All PE-cHL patients were HIV negative. The most common histological subtype was NS (n = 18, 81.8%). Three patients (13.6%) were diagnosed as MC, and 1 patient could not be subclassified. Of the 274 PN-cHL patients treated in the same period, 77 (28.1%) were at advanced stage. Except of stage and B symptoms, other clinical characteristics of PN-cHLs, such as age, gender and histological subtype, showed no significant difference in comparison with those of PE-cHLs. The main baseline clinical characteristics of PE-cHL and PN-cHL patients are shown in .

Table 1. Extranodal lesion site of 22 PE-cHL patients.

Table 2. Characteristics of 22 PE-cHL patients and 274 PN-cHL patients.

Treatment and outcomes

In this study, 4−8 cycles (median: 6) of chemotherapy were administered to all 22 PE-cHL patients as initial treatment. Most (n = 19, 86.4%) of patients received ABVD regimen (adriamycin, bleomycin, vincristine and dacarbazine), while 2 (9.1%) received BEACOPP regimen (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone), and only 1 primary central nervous system cHL patients received MT regimen (methotrexate and temozolomide). Radiotherapies were performed on one primary bone patient and one primary nasopharynx patient after initial chemotherapy for better local disease control. Evaluation of response was available for all 22 patients (). The overall response rate (ORR) was 95.5%, and 13 (59.1%) patients achieved complete response (CR). Eight patients developed disease recurrences after initial therapy, including 5 (42%) of 12 lung PE-cHL patients and 3 (75%) of 4 bone PE-cHL patients. The ORR and CR rate of 22 PE-cHL cases showed no significant differences compared with 274 PN-cHLs (ORR: 98.5%, p = .280; CR rate: 75.9%, p = .081). However, PE-cHL patients experienced significantly more frequent relapse or progression than PN-cHL patients (36.4% vs. 13.1%, p = .003).

Table 3. Initial therapy regimen and response.

With a median follow-up period of 42 (range, 5–100) months, the estimated 5-year OS rate and 5-year PFS rate of 22 PE-cHL cases were 64.6% and 42.4%, respectively, significantly poorer than those of 274 PN-cHL patients (5-year OS: 97.7%, p = .001; 5-year PFS: 82.2%, p < .001) ( and ). To minimize the bias of stage, PE-cHL patients were matched with PN-cHL patients at a ratio of 1:1 according to age, gender, histological types and stage by propensity score matching. The propensity score of the PE-cHL group and the matched PN-cHL group were 0.152 and 0.153, respectively. B-symptoms showed no significant difference between the PE-cHL group and the matched PN-cHL group. Compared with 22 matched PN-cHL cases, although no significant difference in OS was found (p = .072), the OS rate in 5 years of PE-cHL showed about 30% lower than PN-cHL (5-year OS: 64.6% vs. 92.9%) (). Moreover, PE-cHL still showed significantly unfavorable PFS compared with matched PN-cHL (5-year PFS: 42.4% vs. 79.9%; p = .004) (). Therefore, the prognosis of PE-cHL patients, especially the long term survival, was significantly poorer than that of PN-cHL.

Prognostic factors analyses of PE-cHL

To investigate prognostic factors of 22 PE-cHL patients, univariate factors were tested by Cox regression and the results are listed in . The unfavorable risk factors for early-stage cHL (according to the standard of National Comprehensive Cancer Network) or International Prognostic Score (IPS) for advanced-stage cHL did not show significantly prognostic value in our study. Univariate analysis showed elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and elevated platelet (PLT) were associated with poor PFS (p < .05). No prognostic factor of OS or an independent prognostic factor of PFS was found in this study.

Table 4. Univariate COX hazard analysis of risks factors for PFS and OS of 22 PE-cHL patients.

Discussion

Asymptomatic superficial lymphadenopathy, especially cervical lymphadenopathy, is the majority clinical manifestation of cHL. Extranodal involvements of cHL, such as those in the lung and bone, are less common and usually considered as disease spreading to distant sites. Primary extranodal lymphoma was first recognized at the 1940s [Citation7]. Then in some small case series, primary lymphoma of the lung and gastrointestinal tract were noted [Citation8,Citation9]. Approximately 25%−45% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) were thought to be primary extranodal lymphomas [Citation5], but PE-cHL was not commonly observed. Previous studies on primary extranodal lymphoma, including the studies conducted by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELGS), mainly focused on primary extranodal NHL [Citation10–13]. Almost all the reports of PE-cHL are case series, and therefore the understanding about PE-cHL remains deficient. Here we present a relatively large sample retrospective study to investigate clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of PE-cHL.

The accurate estimation of primary extranodal lymphoma remains controversial. Existing reports of primary extranodal NHL (PE-NHL) basically based on either of the following two criteria: 1) disease rigorously limited to extranodal sites in the absence of any evidence of nodal involvement, or 2) clinically dominant extranodal involvement with the existence of a minor nodal component [Citation5]. We identified PE-cHL as a disease of HL restricted to extranodal organs, with or without regional lymph node involvement and without distant lymph node involvement, according to the fixed designation of primary extranodal lymphoma defined by Dawson et al. [Citation9], which was considered to be appropriate by most clinicians.

In our study, PE-cHL mainly occurring in young males; and the most common histological subtype was NS, which also presented in a previous report [Citation14]. Differing from PN-cHL, initial symptoms of PE-cHL were usually associated with the origination site of disease instead of painless superficial lymph node enlargement. In this study, 10 of 12 primary lung cHL patients presented with cough as the initial symptom, 3 of 4 primary bone cHL patients presented with back pain, and 1 primary central nervous system cHL presented with headache. Nevertheless, other clinical characteristics of PE-cHL, such as age, gender and histological subtype, showed no significant difference in comparison with those of PN-cHL.

Lung was the most common origination site of these 22 PE-cHL cases. According to a study of 40 primary lung lymphoma, 1.5–2.4% were primary lung HL [Citation15], while primary lung cHL was still not frequently seen even if in primary lung lymphoma. Previously reported primary lung HL typically involved the superior portions of unilateral lung [Citation4,Citation16–19], while bilateral infiltrates of lymphoma were also seen [Citation20]. In our study, 3 primary lung cHL patients had bilateral lung involvement and were identified to be multiple primary and in stage IV. As to primary bone lymphoma, unlike NHL mostly involving limb bone, primary bone HL frequently involved axial bone such as spine and clavicle [Citation21–23]. The 4 cases primary bone cHL in our study all involved axial bone. It was reported that nasopharynx involvement only occurred in less than 2% of HL patients [Citation24,Citation25], which was male preponderance [Citation25–28] and had favorable outcomes. Some HL of nasopharynx were Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positive [Citation27,Citation29,Citation30]. Noticeably, the only primary nasopharynx cHL patient in our study was a female with EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization (ISH) positivity in nasopharyngeal lymphoma tissue and achieved complete remission of disease with no relapse after ABVD regimen chemotherapy and involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT). Approximately 95% of primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSLs), as a special pathology type, were diffuse large B-cell lymphomas [Citation31], while primary central nervous system HL was seldom seen. The patient with primary central nervous system HL in our study received a chemotherapy regimen (methotrexate and temozolomide) recommended for PCNSL instead of standard ABVD regimen for HL and achieved complete remission of disease till latest follow-up. One primary adrenal gland cHL case was included in our study, which was the first reported primary adrenal gland cHL. Other uncommon primary extranodal sites of HL like breast and gastrointestinal tract were reported [Citation14,Citation32–34] but were not present in our study.

The treatment outcomes and survival data of PE-cHL are lacking. In a retrospective study of 26 PE-cHL cases [Citation14], the CR rate and ORR of 24 evaluable patients were 58.3% and 70.8%, respectively, and the 5-year OS rate and disease-free survival (DFS) rate were 89.6% and 87.7% respectively. According to a retrospective study of primary lung HL, no case of tumor recurrence or death occurred [Citation16]. However, in our study, PE-cHL patients exhibited a significantly higher recurrence rate and poorer survive compared with PN-cHL patients, indicating that more intensive treatment strategy may be needed for PE-cHL patients. Further investigations with a larger sample may reveal the outcomes of PE-cHL more comprehensively.

Many prognostic factors of early-stage and advanced-stage cHL are widely used, but the prognostic factors of PE-cHL have not been well recognized. For primary lung HL, a retrospective study of 15 cases showed that aged patients presenting with B symptoms and tumor cavitation had an unfavorable clinical outcome [Citation35]. Furthermore, it was reported that age, albumin, LDH, clinical stages and EBER (+) were prognostic factors of PE-cHL [Citation14]. Despite of that, according to our study, age, B symptoms and albumin were not associated with OS or PFS of PE-cHL. The unfavorable risk factors or IPS did not show prognostic value in our study. The prognostic factor of PE-cHL may differ from the common cHL for its unique onset mode. In our study, LDH and PLT were prognostic factors of PE-cHL. A better understanding of the prognostic factors of PE-cHL still depends on further research.

In conclusion, our study identified the clinical characteristics, outcomes and prognostic factors of PE-cHL by retrospective analysis of 22 patients. PE-cHL commonly occurred in young males. The initial symptoms of PE-cHL were usually associated with the origination site of disease but not painless superficial lymph node enlargement. The most frequent histological subtype of PE-cHL was NS. Although being sensitive to chemotherapy, PE-cHL showed a considerably shorter duration of remission, higher recurrence tendency and poorer survival compared with PN-cHL. Elevated LDH and PLT were poor prognostic factors of PE-cHL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M.S. Lan Mi for statistical method supporting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, Song Y. and Wu M., upon reasonable request.

Notes on contributors

Mingzi Yang is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Lingyan Ping is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Weiping Liu is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Yan Xie is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Aliya is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Yanfei Liu is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Reyizha Nuersulitan is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Jun Zhu is the chief of department of lymphoma, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Meng Wu is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

Yuqin Song is a doctor of department of lymphoma at Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute. The interested research area of the author is the diagnosis and treatment of lymphoma.

ORCID

Mingzi Yang http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4011-235X

Weiping Liu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0367-1411

Additional information

Funding

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the world Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569

- Mottok A, Steid C. Biology of classical Hodgkin lymphoma: implications for prognosis and novel therapies. Blood. 2018;131(15):1654–1665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-772632

- Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010;102(3):83–87.

- Cooksley N, Judge DJ, Brown J. Primary pulmonary Hodgkin’s lymphoma and a review of the literature since 2006. BMJ Case Rep. 2014.

- Cavalli F, Stein H, Zucca E. Extranodal. London: Informa; 2008.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800

- Gall EA, Mallory TB. Malignant lymphoma. A clinicopathologic survey of 618 cases. Am J Pathol. 1942;18:381–429.

- Beck WC, Reganis JC. Primary lymphoma of the lung; review of literature, report of one case, and addition of eight other cases. J Thorac Surg. 1951;22:323–328.

- Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant tumors of the intestinal tract. report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;49:80–89. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004921319

- Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: the International extranodal lymphoma study group experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(2):266–272. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.139

- Zucca E, Conconi A, Mughal TI, et al. Patterns of outcome and prognostic factors in primary large-cell lymphoma of the testis in a survey by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):20–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.141

- International Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(14):987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402

- Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Oldani E, et al. The modified International Prognostic Index can predict the outcome of localized primary intestinal lymphoma of both extranodal marginal zone B-cell and diffuse large B-cell histologies. Br J Haematol. 2002;118(1):218–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03613.x

- Ma J, Wang Y, Zhao H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 26 patients with primary extranodal Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(8):5045–5050.

- Parissis H. Forty years literature review of primary lung lymphoma. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-23

- Rodriguez J, Tirabosco R, Pizzolitto S, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma presenting with exclusive or preponderant pulmonary involvement: a clinicopathologic study of 5 new cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10(2):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.07.014

- Hage H EI, Hossri S, Samra B, et al. Primary pulmonary Hodgkin's lymphoma: a rare etiology of a cavitary lung mass. Cureus. 2017;9(8):1620.

- Schild MH, Wong WW, Valdez R, et al. Primary pulmonary classical Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(3):341–344. doi: 10.1002/jso.23624

- Aljehani Y, Al-Saif H, Al-Osail A, et al. Multiloculated cavitary primary pulmonary Hodgkin lymphoma: case series. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11(1):90–97. doi: 10.1159/000486824

- Binesh F, Halvani H, Taghipour S, et al. Primary pulmonary classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011.

- Citow JS, Rini B, Wollmann R, et al. Isolated, primary extranodal Hodgkin's disease of the spine: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(2):453–456.

- Fried G, Ben Arieh Y, Haim N, et al. Primary Hodgkin's disease of the bone. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;24(3):204–207. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950240312

- Ha-ou-nou FZ, Benjilali L, Essaadouni L, et al. Sacral pain as the initial symptom in primary Hodgkin's lymphoma of bone. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9(3):511–513. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.119365

- Malis DD, Moffat D, McGarry GW. Isolated nasopharyngeal Hodgkin’s disease presenting as nasal obstruction. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52(5):343–346.

- Hollander SL. Uncommon presentations of Hodgkin's disease. case 2. Hodgkin's disease of the nasopharynx. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):195–196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.116

- Anselmo AP, Cavalieri E, Cardarelli L, et al. Hodgkin's disease of the nasopharynx: diagnostic and therapeutic approach with a review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 2002;81(9):514–516. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0504-1

- Abbes I, Mrad K, Sassi S, et al. Primary Hodgkin's disease of the nasopharynx: a rare but bona fide disease. Pathologica. 2002;94(6):314–316. doi: 10.1007/s102420200056

- Bensouda Y, El Hassani K, Ismaili N, et al. Primary nasopharyngeal Hodgkin's disease: case report and literature review. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:116. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-116

- Molony NC, Stewart A, Ab-See K, et al. Pathology in focus Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:103–105. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100140022

- Kochbati L, Chraïet N, Nasr C, et al. Hodgkin disease of the nasopharynx: report of three cases. Cancer Radiother. 2006;10(3):142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2005.10.012

- Chiavazza C, Pellerino A, Ferrio F, et al. Primary CNS lymphomas: challenges in diagnosis and monitoring. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:3606970. doi: 10.1155/2018/3606970

- Zarnescu NO, Iliesiu A, Procop A, et al. A challenging case of primary breast Hodgkin's lymphoma. Maedica (Buchar). 2015;10(1):44–47.

- Morgan PB, Kessel IL, Xiao SY, et al. Uncommon presentations of Hodgkin's disease. Case 1. Hodgkin's disease of the jejunum. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):193–195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.072

- Simpson L, Taylor S, Piotrowski A. Uncommon presentations of Hodgkin's disease. Case 3. Hodgkin's disease: rectal presentation. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):196–198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.144

- Yousem SA, Weiss LM, Colby TV. Primary pulmonary Hodgkin’s disease. A clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Cancer. 1986;57(6):1217–1224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6<1217::AID-CNCR2820570626>3.0.CO;2-N