ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: Indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (iNHLs) are considered incurable. Rituximab maintenance and yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (90Y-IT) consolidation are promising post-remission therapies. However, only one randomized phase II trial has compared their efficacies and adverse effects. Here, we compared the efficacy and safety of 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance in iNHL patients.

METHODS: We retrospectively examined 75 iNHL patients with complete or partial response after initial chemotherapy between January 2008 and December 2018. Twenty-seven patients received 90Y-IT consolidation and 48 received rituximab maintenance (every 2 months for 2 years). Progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and time to next treatment (TTNT) were estimated from the start of the treatment, and adverse effects were evaluated.

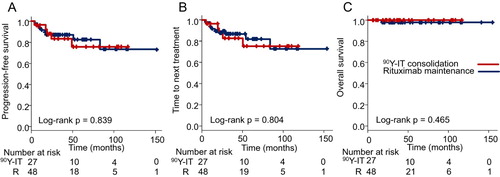

RESULTS: After a median 3.6-year follow-up, the 5-year PFSs of the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups were 75.5% and 82.4%, respectively (log-rank test, p = 0.839), and the 5-year OSs were 100% and 97.8%, respectively (log-rank test, p = 0.465). The corresponding median TTNTs were not reached (log-rank test, p = 0.804). The commonest adverse effect with 90Y-IT consolidation was hematotoxicity; lower rates and grades of cytopenia were observed in patients who received rituximab maintenance. Secondary malignancies were observed in 1 patient (4%) who received 90Y-IT consolidation and 2 patients (4.2%) who received rituximab maintenance (Fisher’s exact test, p > 0.99).

CONCLUSION: 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance were similar with respect to PFS, OS, and TTNT. However, the features and grades of adverse effects significantly differed. Patient-specific characteristics should be considered when deciding post-remission treatments.

Introduction

Indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (iNHL) is one of the commonest lymphoma types, and it generally progresses slowly. Patients with iNHL usually respond to initial treatment but relapse after several years, and the disease seems to be incurable. The main cause of death is lymphoma progression [Citation1]. Therefore, post-remission treatment is an attractive approach to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) and even overall survival (OS).

There are two approaches for post-remission treatment in iNHL, namely, maintenance therapy and consolidation therapy. Rituximab maintenance therapy is a well-established post-remission treatment for patients who responded to first-line chemotherapy. Two-year rituximab maintenance therapy improved PFS in randomized trials [Citation2,Citation3] and OS in a meta-analysis of randomized trials [Citation4]. Therefore, rituximab maintenance therapy has been suggested as a standard of care for patients with iNHL. In contrast, consolidation is a short-term intensive treatment. The efficacy of consolidative radioimmunotherapy (RIT) using yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (90Y-IT) was demonstrated in the First-Line Indolent Trial [Citation5]. 90Y-IT comprises ibritumomab covalently linked to tiuxetan, which chelates yttrium-90. Ibritumomab is a murine monoclonal IgG1 antibody against CD20 and the parent of the genetically modified chimeric antibody rituximab. Following the results of early clinical trials [Citation6–8], 90Y-IT was approved for treating recurrent or refractory iNHL in Japan. However, there has been only one retrospective study [Citation9] and one preliminary result from a randomized phase II study comparing rituximab maintenance and RIT in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) [Citation10]. Therefore, we address the efficacy and safety of 90Y-IT consolidation compared with those of rituximab maintenance in patients with iNHL.

Patients and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective observational study of data from a single institutional database of Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital. We reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed with iNHL between January 2008 and December 2018 who received either 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance after achieving partial or better response to one regimen of induction treatment. iNHL included the following CD20-positive subtypes: follicular (grades 1, 2, and 3a), lymphoplasmacytic, small lymphocytic, and marginal zone lymphoma [Citation11]. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment procedures

Patients who completed induction therapy and achieved partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) started either 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance within 2 months. Patients received 90Y-IT consolidation if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: neutrophil count ≥1.5 × 109/L, platelet count ≥100 × 109/L, and bone lymphoma marrow involvement <25%. If the patient desired to receive rituximab maintenance or did not fulfill the criteria, the patient received rituximab maintenance. 90Y-IT consolidation was performed as follows: the patient received 250 mg/m2 rituximab on days 1 and 8, followed by 111In ibritumomab tiuxetan (130 MBq 111In, 1 mg ibritumomab) on day 1 and 90Y-IT (14.8 mBq/kg, 1 mg ibritumomab) on day 8. The dose of 90Y was reduced to 11.1 mBq/kg if the patient’s platelet count was <150 × 109/L on day 8.

Patients in the rituximab maintenance group received 375 mg/m2 rituximab intravenously once every 8 weeks for 2 years or until disease progression, whichever occurred first [Citation3].

Response to treatment and adverse effects

The tumor response was assessed according to the Lugano classification [Citation12]. The response to 90Y-IT consolidation was evaluated 8–12 weeks after therapy, and the response to rituximab maintenance was evaluated at the end of therapy. Adverse effects during 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.0 [Citation13].

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics and responses to each treatment were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. PFS, OS, and time to next treatment (TTNT) from the first day of either 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance therapy were assessed according to the revised International Working Group criteria [Citation14], calculated using Kaplan-Meier methods, and then analyzed using a log-rank test with a two-sided significance level of p = 0.05 [Citation15]. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR computer software [Citation16].

Results

Patient characteristics

During the follow-up period, 84 patients with iNHL received induction chemotherapy. Seven patients did not achieve PR or CR, and two patients refused maintenance or consolidation treatment. Therefore, 75 patients (90Y-IT consolidation, n = 27; rituximab maintenance, n = 48) with newly diagnosed iNHL were examined. Of the 48 patients who received rituximab maintenance therapy, 30 patients requested this treatment and 18 patients failed to meet 90Y-IT consolidation criteria. Baseline characteristics () and first-line treatments were well balanced between the two groups. There were no patients with bulky masses (>5 cm) at the baseline of this study. In the 90Y-IT consolidation group, 5 patients received a reduced dose of 90Y (11.1 mBq/kg) owing to platelet counts <150 × 109/L.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at study entry.

Efficacy

After a median 3.6-year (range, 0.5–13.1 years) follow-up period, the 5-year PFSs were 75.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 48.9–89.5%) and 82.4% (95% CI, 65.1–91.6%) in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively (log-rank p = 0.839; , A). The median TTNT was not reached in either group (log-rank p = 0.804; , B). The 5-year OSs were 100% (95% CI, 100–100%) and 97.8% (95% CI, 85.3–99.7%) in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively (log-rank p = 0.465; , C).

Figure 1. Progression-free survival (A), time to next treatment (B), and overall survival (C) after post-remission treatment. Abbreviations: Yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation, red line; rituximab maintenance, dark blue line. 90Y-IT, yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan.

Table 2. Outcomes after 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation and rituximab maintenance.

In the rituximab maintenance group, 34 patients (71%) completed 2-year rituximab maintenance therapy, 3 (6%) were continuing to receive therapy at the time of the analysis, 5 (10%) discontinued therapy because of progressive disease (PD), and 6 (13%) discontinued therapy because of adverse effects (4 patients) or at the patient’s requests (2 patients).

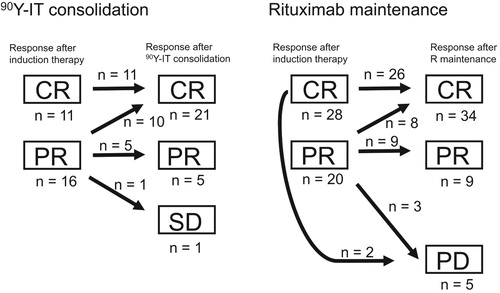

The overall response rates (rates of CR + PR) were 96% and 90% in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively (). Thirty-six patients had achieved PR at the start of the post-remission treatment (16 and 20 patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively), and 10 (63%) and 8 (40%) patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively, showed PR to CR conversion after 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.315, ). In contrast, 1 (4%) and 5 (10%) patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively, did not respond to the treatments or relapsed and received second-line treatments (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.410, ). No patient developed transformation to aggressive lymphoma during the follow-up period.

Figure 2. Disease response status conversion before and after yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation (left), or rituximab maintenance (right). Abbreviations: 90Y-IT, yttrium-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan; R maintenance, rituximab maintenance; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Thirteen patients had relapsed after post-remission treatment (5 and 8 patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively) at the time of the analysis. Among them, 11 patients (3 and 8 patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively) received rituximab + bendamustine chemotherapy, and 7 patients (4 and 3 patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively) received rituximab monotherapy. In the rituximab maintenance group, 4 patients received 90Y-IT therapy after lymphoma recurrence. One patient in the rituximab maintenance group received autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplantation.

Subgroup analyses by age, sex, histopathology, stage, bone marrow involvement, and disease status at the start of post-remission treatment indicated no significant difference in the 5-year PFS between the two groups ().

Table 3. 5-year PFS with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation versus rituximab maintenance according to subgroup.

Safety

Adverse effects are described in . Hematologic toxic effects were the commonest adverse effects in the 90Y-IT consolidation group. Grade 3–4 neutropenia and grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia 1–2 months after 90Y-IT consolidation were observed in 22 patients (81%) and 13 patients (48%), respectively. Eight patients (30%) received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and 8 (30%) received platelet transfusion in the 90Y-IT consolidation group. One patient (4%) in the 90Y-IT consolidation group experienced febrile neutropenia. Lower rates and lower grades of cytopenia were observed in the rituximab maintenance group. The frequencies of non-hematologic adverse effects were comparable between the two groups. One patient experienced worsened asthma (to grade 3) during rituximab maintenance, and treatment was discontinued at 18 months. Another patient developed severe aplastic anemia during rituximab maintenance, and treatment was discontinued at 10 months.

Table 4. Adverse events of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation and rituximab maintenance.

Secondary malignancies were observed in 2 (4.2%) and 1 (4%) patient in the rituximab maintenance and 90Y-IT consolidation groups, respectively. In the rituximab maintenance group, 1 patient (an 83-year-old woman with marginal zone lymphoma) developed breast cancer 18 months after beginning rituximab maintenance. Another patient (a 58-year-old man with FL) developed renal cell carcinoma 110 months after starting rituximab maintenance. In the 90Y-IT consolidation group, 1 patient (an 82-year-old man with FL) developed gastric cancer and prostate cancer 18 and 20 months, respectively, after 90Y-IT consolidation. The frequency of secondary malignancy did not differ between the groups (Fischer`s exact test, p > 0.99).

One death (accidental injury) was observed in the rituximab maintenance group at the time of analysis. No patients who were hepatitis B virus carriers (8 and 14 patients in the 90Y-IT consolidation and R maintenance groups, respectively) had developed hepatitis B virus reactivation at the time of analysis.

Discussion

90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance after induction chemotherapy improve PFS, with hazard ratios of 0.40–0.55 and 0.465, respectively [Citation2,Citation3,Citation17]. However, only one prospective randomized trial directly compared outcomes after 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance treatments [Citation10].

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of 90Y-IT consolidation compared with that of rituximab maintenance after induction therapy in patients with iNHL in terms of PFS, OS, and TTNT. Of the 48 patients who received rituximab maintenance therapy, 30 patients preferred this treatment to 90Y-IT consolidation because of their prior experience with rituximab administration. The 5-year PFS were 75.5% and 82.4% in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively. 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance also showed similar OS and TTNT rates. The CR rates were 78% and 71% in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups, respectively. The conversion rates from PR to CR in the 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance groups were 63% and 40%, respectively. These conversion rates are compatible with those reported previously [Citation17]. The conversion rate in the 90Y-IT consolidation group tended to be higher than that in the rituximab maintenance group, but the difference was not significant. In the rituximab maintenance group, 5 patients experienced PD, but PD was not observed in the 90Y-IT consolidation group. These data indicate 90Y-IT consolidation might have benefit for short-term disease control. In subgroup analysis, we observed no significant differences between patients in the two groups when examining any of the categories. These results suggest that 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance have similar efficacy in all analyzed categories of patients.

However, these two post-remission treatments had different outcomes in terms of adverse effects. Hematologic toxicity in the short term and secondary malignancy in the long term are major concerns in patients treated with RIT [Citation5]. Among patients receiving 90Y-IT consolidation therapy in this study, 22 (81%) experienced grade 3–4 neutropenia, 13 (48%) experienced grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia, 8 (30%) received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, 8 (30%) received platelet transfusion, and 1 (4%) developed febrile neutropenia and needed to receive antibiotics. However, no life-threatening hematologic or non-hematologic adverse effects were observed. Moreover, no patients developed acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome, and no difference was observed in the frequency of secondary solid tumors between the two groups. A previous study indicated that the CD34-positive cell yield was significantly lower in patients previously treated with 90Y-IT consolidation than in patients who did not undergo RIT [Citation18]. We also experienced difficulty in collecting hematopoietic stem cells from peripheral blood. This patient was administered 90Y-IT as consolidation after the first relapse (the case is not included in this study for this reason). Because autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after 90Y-IT consolidation is considered in many patients, we should be aware of this issue. Regarding rituximab maintenance, previous studies [Citation3,Citation19,Citation20] found that infection is the commonest adverse effect. However, this therapy seems to be well tolerated, with a limited number of adverse effects resulting in treatment discontinuation, and easy to administer, and no increased risk of secondary malignancy or effect on hematopoietic stem cell collection. In this study, mild hypoproteinemia, which manifests as a decrease in serum immunoglobulin levels, was observed in eight patients, and the incidence of infectious events was not increased in the rituximab maintenance group. In previous studies [Citation3,Citation21], withdrawal from rituximab maintenance because of toxicity was observed in approximately 4% of patients. In this study, 2 of 48 patients (4.2%) withdrew treatment. One of these patients experienced worsening asthma, and another developed aplastic anemia during rituximab maintenance, necessitating discontinuation of rituximab maintenance therapy. Previous studies reported recurrent infections, neutropenia, severe allergic reaction, or arrythmias as reasons for withdrawal from rituximab maintenance [Citation21,Citation22]. Worsening asthma and aplastic anemia were not observed in previous studies. The patient who developed aplastic anemia had concomitant autoimmune disease, which may have contributed to developing aplastic anemia. Further studies with a greater number of patients are necessary to obtain information about these adverse effects.

There are some practical considerations needed to decide between RIT and rituximab maintenance therapy. First, a previous phase III study that compared rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone (CHOP) vs. CHOP followed by RIT induction treatment in patients with FL [Citation23], negative TP53 mutations [Citation24], and normal serum β2-microglobulin (sβ2MG) at diagnosis [Citation25] showed longer PFS in CHOP-RIT patients. Therefore, RIT might be suitable for low risk patients. Second, 90Y-IT treatment is not readily available at all institutions [Citation26], and primary physicians need to refer patients to an institution where 90Y-IT treatment is available. Patient accessibility is also an important factor to consider. Additionally, in Japan, the cost of 90Y-IT treatment is approximately 50,000 US dollars. The cost of rituximab maintenance for 2 years (12 treatment cycles) is approximately 20,000 US dollars. Moreover, if the patient instead receives biosimilar rituximab, the cost of rituximab maintenance is 30% lower. Therefore, rituximab maintenance seems more economically preferable.

Recently, post-remission 131I-tositumomab RIT followed by 4-year rituximab maintenance in untreated FL patients was investigated in a single-arm trial [Citation27]. This trial showed excellent outcomes, with 3- and 5-year PFS of 90% and 85%, respectively. However, only 41 (59%) of 69 patients proceeded to maintenance treatment and completed 4-year rituximab maintenance. The authors concluded that 4-year rituximab maintenance is not feasible for many patients. Because PFS in that study was similar to the 5-year PFS we observed with both 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance post-remission treatments, post-remission treatments using RIT consolidation followed by rituximab maintenance may be overtreatment for iNHL.

Obinutuzumab-based immunochemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance achieves longer PFS than rituximab maintenance in patients with FL [Citation28]. In the obinutuzumab era, we might need further investigation to compare 90Y-IT consolidation and rituximab maintenance with obinutuzumab maintenance in real-world settings.

This study has several limitations. Our study was non-randomized, retrospective, and based on a small number of patients with heterogeneous histopathological iNHL. Because of the indolent nature of iNHL, long-term follow-up is needed to confirm prognosis and adverse effects, including the potential for secondary malignancies in patients who received 90Y-IT consolidation treatment. Large-scale randomized studies are necessary to confirm our results.

A clinical decision about which treatment, 90Y-IT consolidation or rituximab maintenance, is preferable as a post-remission therapy should be based on the effectiveness, adverse effects, convenience, and cost of treatment, as well as biological features of the lymphoma. For example, if it is too difficult for the patient to visit the hospital every 2 months for 2 years, 90Y-IT consolidation is preferable because there are few adverse effects after the period of post-treatment myelosuppression. Patients who achieved only PR after induction treatment, had FL with normal sβ2MG, or had no TP53 mutation at diagnosis might also benefit from 90Y-IT consolidation. In contrast, we should adopt rituximab maintenance therapy for women of childbearing age.

In conclusion, we indicated that 90Y-IT consolidation has similar efficacy to rituximab maintenance as a post-remission treatment in terms of PFS, OS, and TTNT in real-world settings. However, these treatments have different characteristics and adverse effect profiles. Patient backgrounds should be assessed to determine which treatment would be more suitable.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the patients who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr Masaki Iino is Director of the department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Stem Cell transplantation, and the Ambulatory Therapeutic Cancer Center at Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital in Japan. He is also Clinical professor at the Yamanashi University, School of Medicine and the Yamanashi Prefectural University, Graduate School of Nursing.

Dr Yuma Sakamoto and Dr Tomoya Sato are hematologists of the department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Stem Cell transplantation at Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital.

ORCID

Masaki Iino http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3471-0890

References

- Sarkozy C, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Cause of death in follicular lymphoma in the first decade of the rituximab era: a pooled analysis of French and US cohorts. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):144–152. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.00400.

- Hochster H, Weller E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Maintenance rituximab after cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone prolongs progression-free survival in advanced indolent lymphoma: results of the randomized phase III ECOG1496 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1607–1614. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1561.

- Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):42–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7.

- Vidal L, Gafter-Gvili A, Salles G, et al. Rituximab maintenance for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(23):1799–1806. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr418.

- Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. 90Yttrium-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation of first remission in advanced-stage follicular non-hodgkin lymphoma: updated results after a median follow-up of 7.3 years from the international, randomized, phase III first-line indolent trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1977–1983. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6400.

- Witzig TE, Gordon LI, Cabanillas F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yttrium-90–labeled ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy versus rituximab immunotherapy for patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade, follicular, or transformed B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2453–2463. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.11.076.

- Gordon LI, Molina A, Witzig T, et al. Durable responses after ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy for CD20+ B-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of a phase 1/2 study. Blood. 2004;103(12):4429–4431. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-11-3883.

- Tobinai K, Watanabe T, Ogura M, et al. Japanese phase II study of 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan in patients with relapsed or refractory indolent B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(1):158–164. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00999.x.

- Spukti EU, Schmidt LH, Schulze A, et al. 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan as a therapeutic alternative for follicular lymphoma (FL): a single-center experience. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(4):514–521. doi:10.1111/ejh.13138.

- Lopez-Guillermo A, Canales MA, Dlouhy I, et al. A randomized phase II study comparing consolidation with a single dose of 90y ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) (Z) vs. maintenance with rituximab (R) for two years in patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma (FL) responding to R-CHOP. preliminary results at 36 months from randomization. Blood. 2013;122(21):369.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the world Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3068. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800.

- Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403.

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. doi:10.2307/2281868 doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452

- Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458. doi:10.1038/bmt.2012.244.

- Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. Phase III trial of consolidation therapy with yttrium-90-ibritumomab tiuxetan compared with no additional therapy after first remission in advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5156–5164. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2015.

- Derenzini E, Stefoni V, Maglie R, et al. Collection of hematopoietic stem cells after previous radioimmunotherapy is feasible and does not impair engraftment after autologous stem cell transplantation in follicular lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(12):1695–1701. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.09.004.

- Ardeshna KM, Qian W, Smith P, et al. Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):424–435. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70027-0.

- O’Brien S, Salles G, Maurer J, et al. Rituximab in B-cell hematologic malignancies: a review of 20 years of clinical experience. Adv Ther. 2017;34(10):2232–2273. doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0612-x.

- Van Oers MHJ, Van Glabbeke M, Giurgea L, et al. Rituximab maintenance treatment of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term outcome of the EORTC 20981 phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2853–2858. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5827.

- Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular. Blood. 2006;108(13):4003–4008. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725.

- Press OW, Unger JM, Rimsza LM, et al. Phase III randomized intergroup trial of CHOP plus rituximab compared with CHOP chemotherapy plus (131)iodine-tositumomab for previously untreated follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: SWOG S0016. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):314–320. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4101

- Burack R, Li H, Spence JM, et al. Subclonal mutations of TP53 are common in untreated follicular lymphoma and mutation status is predictive of PFS when CHOP is combined with 131-iodine tositumomab but not with rituximab: a analysis of SWOG S0016. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):919. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-99-111399.

- Press OW, Unger JM, Rimsza LM, et al. A comparative analysis of prognostic factor models for follicular lymphoma based on a phase III trial of CHOP-rituximab versus CHOP + 131Iodine-tositumomab. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(23):6624–6632. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1120.

- Schaefer NG, Huang P, Buchanan JW, et al. Radioimmunotherapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: opinions of nuclear medicine physicians and radiation oncologists. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(5):830–838. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.085589.

- Barr PM, Li H, Burack WR, et al. R-CHOP, radioimmunotherapy, and maintenance rituximab in untreated follicular lymphoma (SWOG S0801): a single-arm, phase 2, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5:e102–e108. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30001-2.

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab for the first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1331–1344. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1614598.