ABSTRACT

Background

The standard therapies for autoimmune cytopenias, including idiopathic thrombocytopenia (ITP), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and Evans syndrome (ES), are corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin G. However, the recurrence rate is high.

Method

Data from 80 patients with ITP, AIHA and ES who were refractory to corticosteroids/relapsed and were treated with tacrolimus from January 2018 to January 2019 in Peking Union Medical Colleague Hospital were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

There were 24 males and 56 females, with a median age of 43 (14–81) years, including 66 with ITP, 11 with AIHA and 3 with ES. The median disease duration before tacrolimus was 16 (2–432) months. The complete response (CR) rates were 30.3%, 63.6% and 0%; the overall response (OR) rates were 63.6%, 72.7% and 66.7% for ITP, AIHA and ES, respectively; and the median time to response was 3 (2–10) months. In a median of 18 (10–24) months of follow-up time, 21.4% of ITP patients relapsed at a median time of 7 months. No relapse was found for patients with AIHA and ES. Side effects occurred in 16.3% of patients, including elevated creatinine (N = 3, 3.8%), gastrointestinal reactions (N = 3, 3.8%), and pulmonary infection (N = 2, 2.5%), and resulted in 3 patients stopping tacrolimus. The OR rate was found to be related with age (P = 0.01) but not with sex (P = 0.62), the duration of disease (P = 0.66), tacrolimus concentration (P = 0.99) or disease type (P = 0.84).

Conclusion

Tacrolimus can achieve a durable response with mild side effects in patients with steroid-refractory/relapsed autoimmune cytopenias. Patients with younger age had a better response.

Autoimmune cytopenias, including immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), and Evans syndrome (ES), are diseases caused by autoimmune attack due to various reasons, and patients can present with single- or multilineage cytopenia. Autoimmune cytopenias can be idiopathic or secondary to other diseases. The first-line treatment of autoimmune cytopenias includes corticosteroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIG), with an efficacy of 60–80%, but many patients ultimately relapse [Citation1–4]. For patients with autoimmune cytopenias, relapse or corticosteroid dependence sometimes can be a bigger problem than no reaction to the treatment because patients can die of toxicities caused by high doses and long-term use of corticosteroids.

Tacrolimus, an immunosuppressive agent, is usually used to prevent or treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after organ transplantation. Recent studies showed that tacrolimus can also be used for refractory autoimmune-related systemic diseases, such as systematic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome [Citation5–7]. Recently, there have been a few case reports of successful treatment with tacrolimus for autoimmune cytopenias, such as refractory severe ITP after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation or refractory Evans syndrome [Citation8,Citation9]. In this study, data from 80 patients with autoimmune cytopenias who had failed/relapsed with corticosteroids ± IVIG treatment and were treated with tacrolimus were collected. The efficacy, side effects and relapse rate were recorded and analyzed.

Material and methods

Patients

From January 2018 to January 2019, data from patients diagnosed with refractory/relapsed autoimmune cytopenias who had been treated with tacrolimus in Peking Union Medical Colleague Hospital and met the following criteria were analyzed retrospectively: age ≥14 years old; diagnosed with autoimmune cytopenias [Citation10] (documented autoantibody and/or a history of documented clinical response to steroids); treatments needed before tacrolimus; ITP with platelets <30 × 109/L, hemoglobin <100 g/L for AIHA, or either of the above conditions for ES; and failed/relapsed to previous corticosteroid treatment with or without IVIG. Furthermore, patients who had been treated with other second-line therapies had to stop the treatment for at least 6 months before tacrolimus. Those who had autoimmune cytopenias secondary to other disorders or who had malignancies were excluded. Patients had to sign the informed consent form before data were collected. The study was approved by ethics committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment

Tacrolimus was given at a dose of 1 mg bid, and the dose was adjusted to maintain the trough concentration of tacrolimus at approximately 4–10 ng/ml. Patients who were being treated with corticosteroids were tapered as scheduled, and all of them had stopped the steroids within 3 months. Patients were treated with tacrolimus for at least 6 months before the efficacy was evaluated, and those with a favorable response were treated continuously for one and a half years and tapered gradually afterwards. Patients were asked to come back once per month for three months and then once every three months. All adverse events were recorded, and the regular tests, including blood cell count, reticulocytes, liver and kidney function, and concentration of tacrolimus, were performed.

Response criteria

For ITP, complete response (CR) was defined as platelet count ≥100 × 109/L and absence of bleeding; partial response (PR) was defined as platelet count ≥30 × 109/L and absence of bleeding or at least a doubling of the baseline platelet count; and no response (NR) was defined as any platelet count lower than 30 × 109/L or less than doubling of the baseline count [Citation1,Citation10]. For AIHA, CR was defined as a normal hemoglobin level in the absence of any recent transfusion and ongoing hemolysis; PR was defined as hemoglobin level ≥100 g/L or at least a 20 g/L increase from the pretreatment level; and NR was defined as hemoglobin level ≤100 g/L or an increase less than 20 g/L from the pretreatment level [Citation11]. For ES, CR was defined as meeting the criteria of CR for both ITP and AIHA; PR was defined as meeting the criteria of PR for either ITP or AIHA; and NR was defined as both platelet and hemoglobin levels that did not reach PR levels of ITP and AIHA [Citation11]. Overall response (OR) was defined as CR + PR. Relapse was defined as loss of CR or PR during the follow-up period for those who had responded. Response was evaluated at three and six months and at the end of the follow-up after tacrolimus treatment.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported in terms of absolute frequencies and percentages for qualitative data. Distribution of data regarding continuous variables was described in terms of a median with the range. Comparisons of laboratory values pre- and post-tacrolimus were performed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the possible influencing factors for response. All tests were two-tailed, and a P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated by GraphPad Prism software to show the response rates of ITP, AIHA and ES. SPSS (version 22.0) and GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0) were used for the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 80 patients were enrolled, including 24 males and 56 females; 66 were diagnosed with ITP (20 males and 46 females), 11 with AIHA (4 males and 7 females) and 3 with Evans syndrome (ES) (3 females) (). The median age of all patients was 43 years (range, 14 to 81 years), and the median disease duration before tacrolimus was 16 months (range, 2 to 432 months). For patients with ITP, 16.7% (11/66) had no response to corticosteroids, 78.8% (52/66) were corticosteroid-relapsed or corticosteroid-dependent, and 4.5% (3/66) could not tolerate corticosteroids. Other therapies before tacrolimus, including IVIG (N = 8), cyclosporine (N = 8), eltrombopag (N = 12), splenectomy (N = 3), vincristine (N = 1) and sirolimus (N = 1), had been used in 26 patients, and all had failed and had been stopped for at least 6 months. For patients with AIHA, 36.4% (4/11) failed to respond to corticosteroids, and 63.6% (7/11) were corticosteroid dependent. Similarly, 36.4% (4/11) of patients had received other second-line therapies, including rituximab (N = 1), bortezomib (N = 2), and rituximab combined with bortezomib (N = 1), with no response, and had been stopped for more than 6 months. For patients diagnosed with ES, 33.3% (1/3) did not react to steroids, and 66.7% (2/3) were steroid dependent. No other second-line therapies had been used for the three enrolled patients who could not tolerate steroids. For all patients, the trough concentration of tacrolimus was monitored and maintained between 4 and 10 ng/ml. However, special efforts were made to balance patients’ tolerance and side effects to achieve an optimal response.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of enrolled autoimmune cytopenia patients.

Efficacy

Of all the patients with autoimmune cytopenias, the median time for tacrolimus treatment was 15 months (6–24) months. The median follow-up time was 18 months (10–24 months). Overall, 65% (52/80) of patients had reached at least PR. Among them, 33.8% (27/80) achieved CR, and 31.3% (25/80) achieved PR. The median time for response was 3 months (2–10 months). Most of the patients who continued tacrolimus therapy had steady improvement or remained stable during the follow-up period, except for nine patients with ITP who relapsed during the follow-up period. No malignancies were documented during the follow-up period.

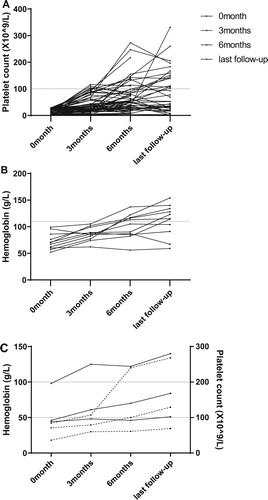

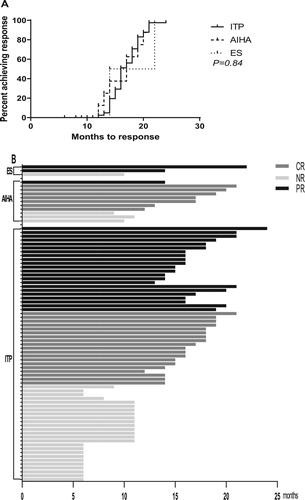

For patients with ITP, the median time for tacrolimus treatment was 14.5 months (6–24 months). The median follow-up time was 18 months (10–24 months). In total, 30.3% (20/66) achieved CR, and 33.3% (22/66) achieved PR, making the OR rate 63.6% (42/66, and ). The median time for response was 4 months (3–6 months). Overall, 21.4% (9/42) patients relapsed during the follow-up period, and the median time of relapse was 7 months (5–13 months, , and B).

Figure 1. Tacrolimus improved cytopenia in patients with different diseases. (A) Platelet changes in patients with ITP at different time points. (B) Hemoglobin changes in patients with AIHA at different time points. (C) Platelet and hemoglobin changes in patients with ES. Each line represents a single subject. The dotted line depicts the normal thresholds for hemoglobin and platelets.

Figure 2. Times to response on tacrolimus in patients with ITP, AIHA and ES. (A) Times to achieve OR on tacrolimus in patients with ITP, AIHA and ES. No significant difference was found among different diseases (P = 0.84). (B) Histogram demonstrating the total times on tacrolimus with different diseases. The different colors reflect whether the patients achieved a PR (black), CR (gray), or NR (white).

For patients with AIHA, the median time for tacrolimus treatment was 14 months (9–21 months), and the median follow-up time was 17 months (12–24 months). A total of 72.7% (8/11) of patients had a response to tacrolimus. Among them, 63.6% (7/11) achieved CR, and 9.1% (1/11) achieved PR ( and ). The median time for response was 3 months (2–10 months). No patients relapsed during the follow-up period (, and B).

For patients with ES, the median time for tacrolimus treatment was 14 months (10, 14, and 22 months), and the median follow-up time was 16 months (14, 16, and 24 months). Overall, 66.7% (2/3) of patients achieved PR, and no CR was observed (B). The times to response were 3 and 4 months, respectively. No patients relapsed during the follow-up period (, and B).

Side effects

Thirteen patients (16.3%, 13/80) had side effects during tacrolimus treatment, including elevated creatinine (N = 3, 3.8%), gastrointestinal reactions (N = 3, 3.8%), pulmonary infection (N = 2, 2.5%), swollen feet and hand tremors (N = 2, 2.5%), dizziness (N = 1, 1.3%), skin rash (N = 1,1.3%) and hypertension (N = 1, 1.3%). Three patients stopped tacrolimus due to severe side effects (1 with an elevated creatinine level of 210 μmol/L and 2 with pulmonary infections); the side effects in the other 10 patients were mild and were relieved automatically or after symptomatic treatment without stopping tacrolimus.

The most common side effect was kidney impairment. However, two cases were mild and recovered after a dosage decrease, but one patient needed to stop tacrolimus due to the overt elevation of creatinine (Scr ≥ 200 μmol/L) and was changed to other agents. Pulmonary infection occurred in two patients who had been treated with steroids for a long time (8 and 12 months, respectively). Patients were admitted to the hospital for systemic treatment, and tacrolimus was stopped. They all recovered and continued tacrolimus for the remaining follow-up time. Blood cell counts and biochemical parameters were also monitored after tacrolimus therapy. No treatment-related leukopenia was observed. No severe liver impairment or other biochemical abnormalities were found during the treatment.

Possible factors influencing the effects of tacrolimus

To further analyze the possible factors that may predict the efficacy of tacrolimus, differences in clinical parameters were compared between patents with or without OR. Binary logistic regression analysis indicated that treatment response was related to age (P = 0.01) but not to sex (P = 0.62), duration of disease (P = 0.66), tacrolimus concentration (P = 0.99) or type of disease (P = 0.84) (A) ().

Table 2. Clinical characteristic comparison between patients with or without responses.

Discussion

Although corticosteroids are the first line therapy for patients with autoimmune cytopenia, some patients do not react well or tolerate them, or sometimes they react but relapse after a dose decrease and become corticosteroid dependent. IVIG is also considered a first-line choice, but the effect is not durable in most cases [Citation2]. Other immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine A (CsA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclophosphamide (CTX), azathioprine, and vincristine, have been used as second- or the third-line therapies [Citation4,Citation12,Citation13]. Patients may react to some degree, but the rate of relapse or side effects is high. Recently, TPO-receptor agonists (i.e. romiplostim or eltrombopag) have been widely used in ITP and ES, and rituximab also demonstrates positive effects on various kinds of autoimmune cytopenia. Although well tolerated and effective, both TPO-receptor agonists and rituximab are expensive, and relapse occurs quickly when they are discontinued [Citation4,Citation14]. In addition, patients treated with rituximab may have high infection rates, and the response can be late. Splenectomy is an option, but the risks of infection, thrombotic events and relapse are high [Citation15].

Autoimmune cytopenia is considered a special ‘autoimmune disease’ in which hematologic system manifestations are dominant. In some patients, the condition may be secondary to autoimmune disease, or autoimmune disease can subsequently develop. Tacrolimus has shown some advantages over other immunosuppressive agents, with better reaction rates and fewer side effects for systematic lupus erythematosus, a typical autoimmune disease, indicating that tacrolimus may also work for autoimmune cytopenia [Citation5,Citation16]. Recently, Gergis U [Citation8] reported one patient diagnosed with severe idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation who was refractory to sufficient corticosteroids and IVIG and had a durable response to tacrolimus treatment. Another report by Tabchi S [Citation9] showed that one patient diagnosed with ES achieved CR on tacrolimus, and this patient had failed with corticosteroids, IVIG, splenectomy, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporin, vincristine and HSCT for approximately 10 ten years before the initialization of tacrolimus therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date of tacrolimus on primary autoimmune cytopenia. As a calcineurin inhibitor similar to CsA, tacrolimus can inhibit the production and release of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and interleukin-2 (IL-2) and inhibits IL-2-induced activation of resting T lymphocytes. It has been reported that tacrolimus has a 10–100-times greater immunosuppressive effect than cyclosporine A and fewer side effects [Citation17,Citation18]. Our research showed an encouraging response to tacrolimus, with OR rates of 63.6%, 72.7% and 66.7% for patients with refractory/relapsed ITP, AIHA and ES, respectively, and the median time to response was 3–4 months. The effects of other second-line therapies can be excluded due to the inclusion criteria. Although the response rates were similar, patients with AIHA had a higher CR rate than those with ES and ITP, and patients with ITP had a higher relapse rate than those with AIHA and ES, although the reasons for these differences were not clear. Our report showed a similar result for tacrolimus as that for CsA, which has been recommended as a second-/third-line therapy for autoimmune cytopenia [Citation4,Citation15,Citation19]. Giovanni E. et al. [Citation20] reported on the use of CsA with eight patients with refractory autoimmune hematological disorders (3 AIHA, 4 ITP and 1 ES), and all patients with AIHA and ES obtained CR, while 50% of ITP patients achieved CR, similar to our findings with tacrolimus, but with a very small number of cases. Choudhary D. et al. [Citation19] reported 25 refractory ITP patients treated with CsA, and the OR rate was 44% (36% patients achieved CR, and 8% of patients achieved PR), although 27.7% relapsed during the follow-up period.

Although the relapse rate in our cohort was lower than that with other second-line therapies, once tacrolimus demonstrated efficacy, no head-to-head comparison has been conducted. For example, it has been reported that high-dose dexamethasone can have an OR of 82.2%, but the relapse rate was 42.7% to 53.2%, while the relapse rates for eltrombopag and CsA were 45–50% and 27.7%, respectively [Citation2,Citation19–21]. No relapses were documented in our study for AIHA and ES, probably due to the limited number of patients and the relatively short follow-up time.

Regarding side effects, 16.3% of patients reported various adverse events, which were mild and reversible in most cases. Only three patients stopped tacrolimus due to the side effects. The rate of adverse events was acceptable compared with that of other standard therapies, such as dexamethasone (22.5–56.5%), standard-dose prednisone (46%), CsA (68.9%), MMF (14.3%) and eltrombopag (51.1%) [Citation12–14,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22–24]. Infection was a great concern for those patients because all the patients had been treated with high-dose or long-term corticosteroids, and tacrolimus may bring further sustained immunosuppression effects. Two severe infections that led to hospitalization were reported in our patients, probably due to the previous heavy immunosuppression therapy. Tacrolimus may be added at an earlier stage once the patients do not react to corticosteroids or become corticosteroid dependent. Since it may take at least three months to show the effects of tacrolimus, corticosteroids may be tapered as scheduled unless patients show no reaction at all.

The response was related to age (P = 0.01) but not to sex, duration of disease, tacrolimus concentration or type of disease. According to the literature, age could be an influencing factor [Citation25], supporting our results. AIHA and ES seemed to have higher OR in absolute numbers than ITP, although these differences were not significant due to the limited number of patients. Immune-mediated attack could be the major mechanism for ITP, AIHA and ES; other mechanisms that may also play roles in the response may be different in individual diseases. Although John Chapin et al. reported that sex and duration of disease were independent influencing factors for the response to rituximab-dexamethasone treatment, all the enrolled patients in our study were corticosteroid refractory/relapsed, and we did not have similar findings.

Compared with patients with ITP or AIHA, patients with ES may have less response and higher relapse rates to corticosteroids. In addition, the responses to the regular second-line therapies are also very modest. Most patients with ES may have an increased chance of developing an overt autoimmune disease during the follow-up period. Although the number of patients was very small, tacrolimus achieved a durable response rate of 66.7% at a median of 16 months in our cohort, which may indicate a promising treatment for ES, although a longer period of observation with a larger number of patients is needed.

With its durable response rate, mild side effects and relatively low price, tacrolimus provides an option for patients who are steroid refractory or who have relapsed autoimmune cytopenia. Further prospective trials with larger patient cohorts and longer follow-up times are needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Notes: PLT, platelet count; HGB, hemoglobin; Ret#, absolute reticulocyte count; Cr, creatinine; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TBil, total bilirubin; DBil, direct bilirubin; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; OR, overall response.

Notes: ITP, thrombocytopenia; AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; ES, Evans syndrome.

References

- Takase K, Nagai H, Kadono M, et al. High-dose dexamethasone therapy as the initial treatment for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int J Hematol. 2020;111:388–395.

- Wang L, Xu L, Hao H, et al. First line treatment of adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a real-world study. Platelets. 2020;31:55–61.

- Serris A, Amoura Z, Canoui-Poitrine F, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab for systemic lupus erythematosus-associated immune cytopenias: A multicenter retrospective cohort study of 71 adults. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:424–429.

- Norton A, Roberts I. Management of Evans syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:125–137.

- Lee YH, Lee HS, Choi SJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus therapy for lupus nephritis: a systematic review of clinical trials. Lupus. 2011;20:636–640.

- Zheng X, Zhang X, Liu X, et al. Patient with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder combined with Sjogren’s syndrome relapse free following tacrolimus treatment. Intern Med. 2014;53:2377–2380.

- Pan X, Huang F, Pan Z, et al. Treatment of serologically negative Sjogren’s syndrome with tacrolimus: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(4):300060519893838.

- Gergis U, Ibrahim M, Al-Kazaz M, et al. Successful treatment with tacrolimus of a patient with severe idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e241–e242.

- Tabchi S, Hanna C, Kourie HR, et al. Successful treatment of Evans syndrome with tacrolimus. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:254–256.

- Gilliland BC, Evans RS. The immune cytopenias. Postgrad Med. 1973;54:195–203.

- Miano M. How I manage Evans syndrome and AIHA cases in children. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:524–534.

- Hou M PJ, Shi Y, Zhang C, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for the treatment of steroid-resistant idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Haematol. 2003;70:353–357.

- Mckkmbvt V. Cyclosporin A for the treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura refractory to corticosteroids or splenectomy. British J Haemotol. 2001;114:121–125.

- Mahevas M, Fain O, Ebbo M, et al. The temporary use of thrombopoietin-receptor agonists may induce a prolonged remission in adult chronic immune thrombocytopenia. Results of a French observational study. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:865–869.

- Bylsma LC, Fryzek JP, Cetin K, et al. Systematic literature review of treatments used for adult immune thrombocytopenia in the second-line setting. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:118–132.

- Takahashi S, Hiromura K, Sakurai N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus for induction therapy in patients with active lupus nephritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:282–289.

- Halloran PF, Madrenas J. The mechanism of action of cyclosporine: a perspective for the 90s. Clin Biochem. 1991;24:3–7.

- Miroux C, Morales O, Ghazal K, et al. In vitro effects of cyclosporine A and tacrolimus on regulatory T-cell proliferation and function. Transplantation. 2012;94:123–131.

- Choudhary DR, Naithani R, Mahapatra M, et al. Efficacy of cyclosporine as a single agent therapy in chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 2008;93:e61–e62. discussion e3.

- Giovanni E, Giuseppe L, Marcello B. Long-term salvage treatment by cyclosporin in refractory autoimmune haematological disorders. Br J Haematol. 1996;91:341–344.

- Gonzalez L, Pascual C, Alvarez R, et al. Successful discontinuation of eltrombopag after complete remission in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:E40–E43.

- Liu AP, Cheuk DK, Lee AH, et al. Cyclosporin A for persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia in children. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:1881–1886.

- James B, Bussel GC, Mansoor N, et al. Eltrombopag for the treatment of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N ENGL J MED. 2007;357:2237–2247.

- Giovanni E, Mario L, Giuseppe L, et al. Long-term salvage therapy with cyclosporin A in refractory idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. BLOOD. 2002;99:1482–1485.

- Agrawal P, Nada R, Ramachandran R, et al. Loss of subpodocytic space predicts poor response to tacrolimus in steroid-resistant calcineurin inhibitor-naive adult-onset primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Indian J Nephrol. 2019;29:90–94.