?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objective

This study aimed to compare the cost-effectiveness of these two regimens in hemophilia A patients, under-12-years-old in southern Iran.

Methods

A cost-effectiveness study comparing prophylaxis versus on-demand was conducted on 34 hemophilia patients (24 and 10 patients were on the prophylaxis and on-demand regimens respectively) in 2017. The Markov model was used to estimate the economic and clinical outcomes. The costs were collected from the societal perspective, and the utility criterion was the 'quality adjusted life year (QALY)' indicator. The required data were collected using a researcher-made cost checklist, the EQ5D standard questionnaire and Hemophilia Joint Health Score. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed to determine the robustness of the results.

Results

The means of costs, joint health score and QALY in the prophylaxis regimen were $478,963.1 purchasing power parity (PPP), 96.67, and 11.98 respectively, and in the on-demand regimen were $521,797.2 PPP, 93.46 and 10.99 respectively. The PSA confirmed the robustness of the model's results. The results of the scatter plots and acceptability curves showed that the prophylaxis regimen in 97% of the simulations for the thresholds below $20950 PPP was more cost-effective than on-demand regimen.

Conclusion

Prophylaxis regimen showed the lower costs and higher effectiveness and utility in comparison with the on-demand regimen. It is recommended that prophylaxis should be considered as the standard care for treatment of hemophilic patients.

Introduction

Hemophilia type A (HA) is an autosomal genetic disorder, caused by Factor 8 (FVIII) deficiencies in blood. According to 2015 census, the number of HA patients in the world was 143,323, with 5,369 in Iran, of which 598 patients were in Fars province; while this province ranks third in this respect [Citation1]. Severe HA patients naturally have less than 1 percent of FVIII in their blood and encounter 15–30 bleeding episodes a year, about 60 percent of which occur in their joints [Citation2]. Joint bleeding, in addition to pain and interruption in the normal life process, causes joint stiffness and muscle atrophy resulting from cartilage damage and subsequently results in disabilities in the long run. The treatment of such disabilities is costly and time-consuming. Also, the disability caused by the chronic arthropathy affects the overall quality of life of patients with hemophilia [Citation3,Citation4].

Initially, for the treatment of patients with severe hemophilia, the drug administration method, called on-demand regimen (OD), was used after each bleeding. Then, the standard prophylaxis regimen, including three factor injections each week, was used which was considered as the gold standard care in many countries. Utilizing the prophylaxis regimen (PR) helps to increase the amount of FVIII in blood above 1 percent and changes the patient’s condition from severe to moderate that consequently prevents spontaneous bleeding in joints. Finally, decreasing joint damage improves patients’ quality of life (QOL) [Citation5,Citation6]. The results of several studies such as Fischer et al.'s study (2002) have shown the lower bleeding episodes and lower joint damage in patients with the PR [Citation7]. Moreover, the PR prevents severe bleeding like intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), a major cause of death in HA patients [Citation8]. In addition, the PR leads to significant improvement in HA patients’ QOL and life expectancy. By the use of this regimen, different dimensions of life utility such as mobility, reduced absence from work or educational settings, decreased number of bleeding episodes, and joint condition have been improved. In some countries, it is believed that the PR is not only useful during childhood and adolescence, but also in adulthood [Citation3].

PR can be used in numerous ways and how it is used in one country might be different from another country. In the countries suffering from lower financial resources, the dose and frequency of PR is lower than the standard PR, for example, 20–30 units per kilogram twice a week. The results of Karimi et al.'s study (2016) showed lower bleeding episodes and improved joints condition in severe hemophiliac patients under the age of three by applying the modified prophylaxis regimen [Citation9]. However, it is worth noting that despite extensive studies on treatment protocols, no treatment protocol has been introduced as the best one [Citation10].

On the other hand, HA puts a heavy economic burden on patients as well as governments. In Iran, about 20% of the medicine imports budget is spent on the purchase of drugs for hemophilia patients [Citation11]. In the past, the cost of treatment with the PR was higher than that with the OD, and budget constraints in some countries prevented the PR from becoming prevalent as the standard regimen in the world, and its need for consuming more medicines and higher costs, in comparison with OD, was considered as an important constraint of the PR [Citation12]. On average, a bleeding episode in HA patients consumes 5–10 vials of the clotting factor, while each vial is valued at $ 200 USD. Moreover, in case of operations or driving accidents and severe bleeding, 50–100 vials are required to prevent bleeding. According to 2014 statistics, each HA patient in the U.S.A. has imposed a cost of more than $250,000 USD during his/her lifetime on the healthcare system[Citation13]. In the Netherlands in 2002, annual consumption of an adult patient with the PR was 105,000 international units (IU), which was equal to 210 vials of FVIII, and in Sweden, this amount was 280,000 IU, which was equal to 260 vials in the same year [Citation7].

Long life treatment of HA patients in Italy in 2011 with the PR was estimated to be 110 million Euros, while for the OD it was estimated at 88 million Euros [Citation4]. In Iran, according to the annual report of World Federation of Hemophilia in 2015, the average annual cost of health services for each patient was $15,130 USD and the FVIII consumption per capita in Iran was 2.165 IU. According to studies, the cost of hemophilia treatment is directly related to other complications caused by the disease, such as joint injuries. Therefore, it can be concluded that the PR can result in cost savings through reducing complications and disabilities [Citation14].

Considering the high cost of HA patients treatment and given that Iran is mainly an importer of FVIII, and also due to the high costs of the medicines and the effects of the treatment regimens on the amount of medicine consumption (cost) and these patients’ QOL (utility), the importance of adopting a cost-effective regimen in treating such patients is obvious [Citation15].

The economic evaluation studies on the cost-utility (CU) of the PR versus OD conducted throughout the world have achieved a wide range of results. The results of some studies have shown that the use of PR reduces joint bleeding and has more cost-effectiveness(CE) and CU than OD [Citation16,Citation17]. It is also estimated that the use of PR can reduce the demand for some health care sources in addition to reducing the bleeding and secondary degenerative orthopedic changes and improving the health-related quality of life [Citation18]. Szucs et al. (Citation1996) believed that the real economic benefit of the PR is to prevent a patient from remaining in the hospital or other health care centers [Citation19].

On the other hand, Miners et al. (2013) reviewed 11 articles and found that differences in the methods, time horizons, definitions, and medicine prices have led to their different results and findings, suggesting that regional studies are necessary [Citation20].

To our knowledge, there was only one similar study in Iran conducted on 21 Hemophilia A patients in order to compare PR with OD regimens by calculating only the cost of factor consumed and the bleeding episodes [Citation11]. Therefore, conducting more accurate and comprehensive studies was required. Hence, the present study aimed to compare the cost-effectiveness of PR with OD regimens in the under-12-year-old HA patients of Fars province, Iran in 2017.

Materials and methods

This was a cost-effectiveness (CU) study conducted in 2017 to compare OD and PR amongst the under-12-year-old HA patients of Fars province, in southern Iran, in 2017 from the societal perspective. The study population was 34 patients with severe HA, among whom 24 patients were treated with the PR and 10 patients were treated with the OD. All patients who had the inclusion criteria were studied using census method. The inclusion criteria were: being under the age of 12, suffering from severe congenital deficiency of FVIII, satisfaction of the patients and their parents to participate in the present study, and lack of FVIII inhibitors.

The collected data were analyzed using Tree Age 2011 and Excel 2010 software.

This study was approved by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (Code: IR.SUMS.REC.1395.S1200). Written Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents participating in the present study and all of them were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

Costs

In order to determine the costs, a researcher-made checklist was used, containing the direct medical costs (DMCs), direct non-medical costs (DNMCs) as well as indirect costs (ICs). The required cost data were extracted from the patients’ medical records and invoices, as well as interviews with the patients and their parents. The related costs were calculated according to the tariffs in 2017 and based on the purchasing power parity (PPP) dollar, which was equal to 11948 Rials for one US dollar [Citation21].

In this study, the DMCs consisted of the costs of receiving different clinical services, such as physicians’ visits, laboratory tests, radiographies, nursing services, medicines, hospitalization, medical supplies, physiotherapies, complementary treatments, and auxiliary equipment. To calculate the price of medicines used, the average price of some brands of plasma-derived medicines in the Iranian market was used. The medicine prices were determined by referring to the hospital accounting documents.

The DNMCs included the average costs of accommodation and meals, and transportation paid during their referral to the hospitals and medical centers, which were requested from the patients and their parents.

To calculate the ICs, the ‘human capital approach’ was used. ICs for each patient depended on the daily wages of patients’ and their parents as well as the length of absence from work due to the patient care and nursing. The wages of parents were used to calculate their lost income and lost potential production due to referring to the hospital and outpatient departments in order to accompany the patients.

Outcomes

In this study, the clinical outcomes for comparing the effectiveness of the mentioned regimens were the joint health and utility scores. To investigate the joint health score, the standard questionnaire of ‘Hemophilia Joint Health Score (HJHS)’ was used, which was completed for the studied patients with the cooperation of a hematologist and a physiotherapist. HJHS has been designed by the physiotherapy experts working group of International Prophylaxis Study Group (IPSG) in 2003, and is considered as an international and sensitive tool for evaluating the joint health score in HA patients [Citation22].

In order to assess the utility score, the studied patients’ QOL, the EQ5D standard questionnaire was used, which was completed by interviewing the patients and their parents. This questionnaire has previously been used in some studies on the hemophilia patients’ QOL [Citation23,Citation24]. Then, by using the Iranian values, the obtained scores were changed to numerical utilities. The utility criterion was the ‘quality adjusted life year (QALY)’ indicator, which is a potential measurement criterion for health, and is calculated by multiplying the duration of time spent in a health state (per year) by the utility score related to that health state. The range of QALY is between 0 and 1, while 1 is equal to one healthy year and 0 indicates death.

Medicine doses

In the OD, after the occurrences of bleeding, the patients were treated by 25–30 units of plasma-derived FVIII per kg of body weight. In the PR, patients were injected 20–30 units of plasma-derived FVIII per kg of body weight, 1–3 times per week.

Transition Probabilities

Due to lack of transition probabilities nationwide, the international evidence and the expert opinions were utilized ().

Model structure

Table 1. Transition probabilities amongst the states in the PR and OD regimens.

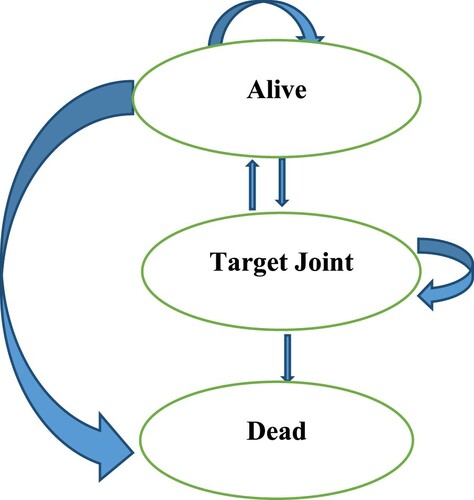

In the present study, the Markov model was used to identify the hemophilia A patients’ clinical and economic status. The outcomes used in the model were the joint health and utility scores. The collected data were analyzed using Excel 2010 and Tree Age 2011 software. The schematic diagram of the Markov model for a hypothetical cohort population of 10000 under-12-years-old hemophilia A patients has been shown in . According to this figure, HA patients who received FVIII could switch from one state to another.

The specified states and their changes, including alive, target joint, and dead, were based on the evidence from previous published studies and expert opinions.

The time horizon was considered as seventy years and the cycles were considered as one year depending on the nature of the disease and changes in its various stages and according to the experts’ opinion [Citation4].

Regarding the time horizon, which was more than one year, the economic and clinical outcomes were discounted with an annual rate of 5% and 3%, respectively. These rates have also been used in other published economic evaluation studies in Iran [Citation25].

Key assumptions of the model:

o All participants entered the model as ‘alive’.

o At the end of the first cycle, the patient either stays ‘alive’ or enters the states of ‘with target joint’ or ‘dead’.

o Those who entered ‘with target joint’ can either enter ‘alive’ or ‘dead’ states, or stay in the ‘with target joint’ state.

o According to Colombo et al.'s study, it is assumed that the life expectancy of the severe hemophilia A patients is equal to that of the general population of Iran [Citation4].

o According to the clinical expert's opinion, having ‘target joint’ does not affect the death.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis:

According to the results of the previous stages, the model was developed in Tree Age software and the extracted data were entered into the model. Then, the costs, effectiveness, and cost- effectiveness of two studied regimens were calculated, and their incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated and compared using the following formula:

Sensitivity Analysis (SA):

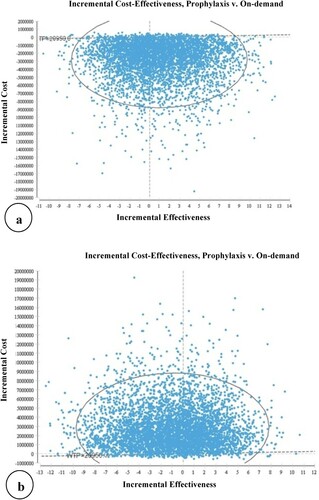

In this study, the probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed to determine the robustness of the results and to examine the effects of uncertainty of the model parameters. In the PSA, instead of indicating parameters as a spot, they are considered as a distribution. To analyze the probabilistic sensitivity, a second-order Monte Carlo simulation was performed using 5000 trials. The PSA results have been presented using a scatter plot of the incremental cost-effectiveness.

Results

In the present study, out of the whole population, 35.29% were under the age of 4, 11.76% between 5 and 7, and 52.94% were between 8 and 12 years old. The average number of referral to the hospital per year in 2016 by the studied patients with the PR and OD regimens was 32 and 14, respectively.

The results showed that the average DMCs, DNMCs and ICs, i.e. the total costs of patients with the PR were higher than those with the OD.

Among the costs, the highest share in both regimens was related to the average DMCs (94.30%) in patients with the PR, and 98.16% in those with the OD, and the lowest share was related to the average ICs in the PR (2.79%) and average DNMCs in the OD (0.71%). Also, the highest average DMCs and DNMCs were related to the clotting factors (96.40% in the PR and 98.74% in the OD) and transportation (62.71% in the PR and 62.57% in the OD), respectively ().

The base-case analyses

Table 2. The average DMCs and DNMCs and ICs of studied patients by the regimens ($PPP).

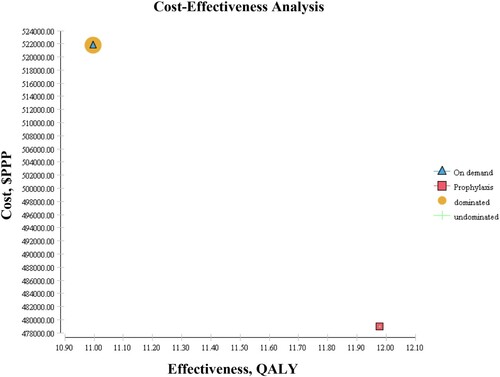

The means of costs and joint health score and utility score in the prophylaxis regimen were, respectively, $478,963.1 purchasing power parity (PPP), 96.67 and 11.98, and in the on-demand regimen were $521,797.2 PPP, 93.46 and 10.99, respectively. Therefore, the prophylaxis regimen showed the lower costs and higher effectiveness and utility in comparison with the on-demand regimen.

The results of CUA have been presented in and and showed that the PR, compared to the OD, had the lower costs and higher utility and was the dominant option.

Uncertainty Analysis

Figure 2. Comparison of the Cost-Effectiveness of the prophylaxis versus on–demand regimens in patients with Hemophilia A Based on the QALY.

Table 3. Comparison of the cost-effectiveness of two studied regimens in Hemophilia A based on the number of QALY using the Markov model.

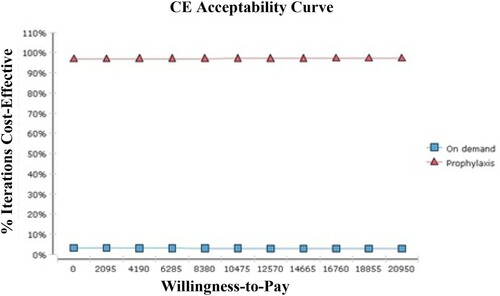

In this study, to perform PSA with the aim of measuring the effects of parameter uncertainty on the results of simulation, models on 5000 trials were estimated. Then, each of them was drawn as a point on the CE axis as the scatter plot of ICER. These points were located in the first quarter of CE plane under the threshold line and, therefore, were acceptable. The CE points showed the uncertainty of results based on the willingness to pay (WTP) range and the threshold ($20950 PPP). According to (a), 97% of simulations in the PR were located in the acceptable areas and below the threshold, while according to (b) in the OD 4% of simulations were in the acceptable areas. Thus, the OD was dominated, and the PR was more cost-effective.

In other words, it can be said that the results of the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves showed that in 97% of simulations the PR was more cost effective treatment for thresholds less than 20950 PPP dollars ().

Discussion

The present study, investigating the hemophilia A as one of the most costly diseases in Iran [Citation1], makes it possible to decide on the basis of actual and regional documents and select the more cost-effective regimen between two prophylaxis and on-demand regimens.

According to the results, the average total costs were lower in the PR than the OD. Some results of the Gharibnaseri et al. [Citation26], Berger et al. [Citation16], Salinas-Escudero et al. [Citation27], Daliri et al. [Citation11], Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Lippert et al. [Citation28], and Fischer et al.'s [Citation7] studies of the related average total costs, DMCs, DNMCs, and ICs are similar to those of the present study.

In the current study, the patients’ joint health score was used as an outcome to measure the effectiveness of studied regimens. The result showed that the effectiveness in the patients with the PR was higher than that in the patients with the OD as a result of keeping FVIII above 1 percent and, therefore, the reduced spontaneous joint bleedings [Citation29,Citation30]. Because the joint health is very important in the assessment of HA patients’ health and joint bleeding is one of the most important complications of HA, in most CE studies conducted on the HA patients the joint health has been considered as an outcome. The results of Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Farrugia et al. [Citation31], Chaugule et al. [Citation32], Fischer et al. [Citation33], Miners et al. [Citation12], and Castro Jaramillo et al.'s [Citation34] studies confirm those of the present study.

In general, in the present study, the PR was more cost-effective and was dominant in comparison with the OD, because of its lower costs and higher effectiveness. In the studies conducted by Colombo et al. [Citation4], Farrugia et al. [Citation31], Daliri et al. [Citation11], Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Salinas-Escudero et al. [Citation27], Fischer et al. [Citation33], Miners et al. [Citation12], and Smith et al. [Citation35], the results showed that although the PR was more cost-effective than OD, it was more expensive. The differences between the results of the present study and those of the studies mentioned above can be due to the fact that in the present study, the modified PR used was based on the patients’ condition and, therefore, had lower clotting factors consumption and costs than other studies that had used standard PR with clotting factors consumption three times a week. In all the studies mentioned above, the effects of the PR on the patients’ joint health and its prevention of long-term disabilities and complications as well as being more cost-effective in the long run have been emphasized. However, Castro Jaramillo et al. [Citation34] in their study concluded that the PR was not cost-effective because of high clotting factors costs and had stated that by reducing the clotting factors price as much as 50%, the PR would be cost-effective.

Concerning the QALY outcome, the results of the present study showed that the PR had more cost-utility than the OD, which can be due to more joint bleeding and its subsequent joint pain and damage in the OD. In other words, the use of PR can decrease the joint bleeding and pain and can prevent the joint problems and disabilities and death due to spontaneous bleeding, and can lead to a better life for patients and the improvement of their quality of life and life expectancy. The results of the Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Farrugia et al. [Citation31], Colombo et al. [Citation4], Giordano et al. [Citation30], and Miners et al.'s [Citation12] studies confirm those of the present study.

According to the results of the current study, the PR had more cost-utility than the OD, indicating that the change from the OD to the PR can improve the patients’ QoL. Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Farrugia et al. [Citation31], Manco-Johnson et al. [Citation36], Fischer et al. [Citation33], and Valentino et al. [Citation37] also have come to the same conclusion. The effects of this change are more evident in the adult patients, because many complications of the disease are long-lasting and negatively affect the QOL in adulthood.

Besides, the PSA confirmed the robustness of the results of the study. So that, the results of the cost-effectiveness scatter plots and acceptability curves showed that in 97% of simulations the PR was more cost-effective option for thresholds less than $20950 PPP. The results of the Risebrough et al. [Citation5], Farrugia et al. [Citation31], Manco-Johnson et al. [Citation36], Fischer et al. [Citation33], and Valentino et al.'s [Citation37] studies are in line with those of the present study. However, the results of Castro Jaramillo et al.'s study [Citation34] are not similar to those of the current study, which can be due to the higher costs of clotting factors in comparison with the threshold (three times the GDP) of the studied country, i.e. Colombia.

This study had some limitations, one of which was that, considering the limited time available, the patients were only examined during one course of treatment. Also, in this study, intangible costs were not taken into account due to the inability to accurately measure them.

It should be noted that considering that the PR and OD regimens are used in other hemophilia treatment centers of Iran, the results of this study can be generalized to other hospitals and medical centers in Iran. However, for generalizing the results of the present study to other countries, it is necessary to be cautious and some issues should be paid attention to, including the epidemiology of the disease and demographic structure, resource availability, prices, outcome assessment by individuals, thresholds, and the use of various effectiveness indices in different studies which may affect their results.

Conclusion

The results showed that the PR was more cost-effective than the OD. Therefore, it can be suggested that the PR regimen be used for the under-12-years-old hemophilia A patients, and policymakers and health managers are required to try to increase the insurance coverage and reduce the out-of-pocket payments of these patients. Furthermore, because most of the HA complications appear in the higher age group, it is proposed that in the future studies, the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of different regimens be studied on the adults as well.

Acknowledgment

The present article was extracted from the thesis written by Zohreh Zahedi and was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences grant number 94-01-07-11112. The researchers would like to thank the studied patients and their parents for their kind cooperation in collecting and analyzing the data. The authors also wish to thank Mr. H. Argasi at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for his invaluable assistance in editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Dorgalaleh A, Dadashizadeh G, Bamedi T. Hemophilia in Iran. Hematol J. 2016;21(5):300–310.

- Coppola A, Di Capua M, De Simone C. Primary prophylaxis in children with haemophilia. Blood Transfus. 2008;6(2):4–11.

- Noone D, O’Mahony B, Prihodova L. A survey of the outcome of prophylaxis, on-demand or combined treatment in 20–35 year old men with severe haemophilia in four European countries. Haemophilia. 2011;17(5):e842.

- Colombo GL, Di Matteo S, Mancuso ME, et al. Cost-utility analysis of prophylaxis versus treatment on demand in severe hemophilia A. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;3:55–61.

- Risebrough N, Oh P, Blanchette V, et al. Cost-utility analysis of Canadian tailored prophylaxis, primary prophylaxis and on-demand therapy in young children with severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):743–752.

- Henry N, Jovanović J, Schlueter M, et al. Cost-utility analysis of life-long prophylaxis with recombinant factor VIIIFc vs recombinant factor VIII for the management of severe hemophilia A in Sweden. J Med Econ. 2018;21(4):318–325.

- Fischer K, Van der Bom G, Molho P, et al. Prophylactic versus on-demand treatment strategies for severe haemophilia: a comparison of costs and long-term outcome. Haemophilia. 2002;8(6):745–752.

- Witmer C, Presley R, Kulkarni R, et al. Associations between intracranial haemorrhage and prescribed prophylaxis in a large cohort of haemophilia patients in the United States. Br J Haematol. 2011;152(2):211–216.

- Karimi M, Eshghi P, Safarpour M, et al. Modified Primary prophylaxis in previously Untreated patients With severe hemophilia A in Iran. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40(3):188–191.

- Fernandes S, Carvalho M, Lopes M, et al. Impact of an individualized prophylaxis approach on young adults with severe hemophilia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40(07):785–789.

- Daliri AA, Haghparast H, Mamikhani J. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against on-demand treatment in boys with severe hemophilia A in Iran. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(4):584–587.

- Miners H, Sabin A, Tolley H, et al. Cost-utility analysis of primary prophylaxis versus treatment on-demand for individuals with severe haemophilia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(11):759–774.

- Dalton R. Hemophilia in the managed care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(6 Suppl):S123–SS30.

- Globe R, Cunningham E, Andersen R, et al. The hemophilia utilization group study (HUGS): determinants of costs of care in persons with haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2003 May;9(3):325–331.

- Blanchette S, O'Mahony B, McJames L, et al. Assessment of outcomes- what is the added value of QoL tools? Haemophilia. 2014 May;20(4):114–120.

- Berger K, Schopohl D, Eheberg D, et al. Prophylactic factor substitution in severe haemophilia A. Hämostaseologie. 2014;34(4):291–300.

- Fischer K, Lewandowski D, Janssen M. Modelling lifelong effects of different prophylactic treatment strategies for severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2016;22(5):e375–e382.

- Klamroth R, Pollmann H, Hermans C, et al. The relative burden of haemophilia A and the impact of target joint development on health-related quality of life: results from the ADVATE Post-authorization Safety Surveillance (PASS) study. Haemophilia. 2011;17(3):412–421.

- Szucs T, Öffner A, Schramm W. Socioeconomic impact of haemophilia care: results of a pilot study. Haemophilia. 1996;2(4):211–217.

- Miners H. Economic evaluations of prophylaxis with clotting factor for people with severe haemophilia: why do the results vary so much? Haemophilia. 2013 Mar;19(2):174–180.

- Purchasing Power Parity. WHO; 2017 [updated 2017; cited 2017 Oct 1]; Available from: http://www.who.int/choice/costs/ppp/en/.

- Saulyte Trakymiene S, Ingerslev J, Rageliene L. Utility of the Haemophilia joint health score in study of episodically treated boys with severe haemophilia A and B in Lithuania. Haemophilia. 2010;16(3):479–486.

- Beheshtipoor N, Bagheri S, Hashemi F, et al. The effect of yoga on the quality of life in the children and adolescents with haemophilia. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2015 Apr;3(2):150–155.

- Barr RD, Saleh M, Furlong W, et al. Health status and health-related quality of life associated with hemophilia. Am J Hematol. 2002 Nov;71(3):152–160.

- Ravangard R, Rezaee M , Keshavarz K, Borhanihaghighi A, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of CinnoVex versus ReciGen in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Iran. Shiraz E-Med J. 2018;19(11):e67363–e67371.

- Gharibnaseri Z, Davari M, Cheraghali A, et al. Cost-utility of prophylaxis VS. On-demand treatment In severe Haemophilia A patients. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A591.

- Salinas-Escudero G, Marıa G-SR, Kely R, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of prophylaxis vs.‘on demand’approach in the management in children with hemophilia A in Mexico. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2013;70(4):290, Ā7.

- Lippert B, Berger K, Berntorp E, et al. Cost effectiveness of haemophilia treatment: a cross-national assessment. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005;16(7):477–485.

- Karimi M, Eshghi P, Toogeh G, et al. Comprehensive management for hemophilia in Iran. 1st ed. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 2008.

- Giordano P, Lassandro G, Valente M, et al. Current management of the hemophilic child: a demanding interlocutor. quality of life and Adequate cost-Efficacy Analysis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;31(8):687–702.

- Farrugia A, Cassar J, Kimber M, et al. Treatment for life for severe haemophilia A–A cost-utility model for prophylaxis vs. on-demand treatment. Haemophilia. 2013;19(4):e228–e238.

- Chaugule SS, Hay JW, Young G. Understanding patient preferences and willingness to pay for hemophilia therapies. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1623–1630.

- Fischer K, Pouw M, Lewandowski E, et al. A modeling approach to evaluate long-term outcome of prophylactic and on demand treatment strategies for severe hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2011;96(5):738–743.

- Castro Jaramillo HE, Moreno Viscaya M, Mejia AE. Cost-utility analysis of primary prophylaxis, compared with on-demand treatment, for patients with severe hemophilia type a in Colombia. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2016;32(5):337–347.

- Smith PS, Teutsch SM, Shaffer PA, et al. Episodic versus prophylactic infusions for hemophilia A: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Pediatr. 1996;129(3):424–431.

- Manco-Johnson M, Abshire T, Shapiro A, et al. Prophylaxis versus episodic treatment to prevent joint disease in boys with severe hemophilia. N Engl J Med. 2007;6(357):535–544.

- Valentino L, Mamonov V, Hellmann A, et al. A randomized comparison of two prophylaxis regimens and a paired comparison of on-demand and prophylaxis treatments in hemophilia a management. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(3):359–367.

- Mannucci PM, Schutgens RE, Santagostino E, et al. How I treat age-related morbidities in elderly persons with hemophilia. Blood. 2009 Dec 17;114(26):5256–5263.

- Population and Migration Information and Statistics Office. National Organization for Civil Registration; 2017 [updated 2017; cited]; Available from: https://www.sabteahval.ir/avej/tab-1499.aspx.

- van Genderen R, van Meeteren L, van der Bom G, et al. Haemophilia activities list – pediatric (PedHAL) World Federation of Hemophilia; [cited 2016 May 22]; Available from: http://www.wfh.org/en/page.aspx?pid=875.