ABSTRACT

Objective and importance

Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) is a benign and rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytic proliferative disorder. Laryngeal involvement is an unusual site of extranodal involvement of RDD. Laryngeal RDD can cause life-threatening airway obstruction that requires effective control of the disease. In this study, we report three cases of laryngeal RDD with excellent and durable responses to thalidomide.

Clinical presentation

Patient 1 was a 39-year-old male who presented with a two-year history of nasal obstruction. Patient 2 was a 26-year-old woman who presented complaining of a hoarse voice for one year. Patient 3 was a 24-year-old man who presented with complaints of a hoarse voice and progressing dyspnea for five months. Electronic laryngoscopy revealed submucous nodular lesions in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and larynx of the three patients. Biopsy of the lesions showed large histiocytes with abundant pale cytoplasm which were S-100 and CD68 positive consistent with RDD.

Intervention

Before thalidomide treatment, patient 1 received chemotherapy and six times surgical excision due to the recurrence of laryngeal lesions. Patient 2 failed steroid treatment. Patient 3 underwent an emergency tracheostomy due to airway obstruction. All three patients then received thalidomide 100 mg/d treatment and achieved satisfactory and durable responses with the longest follow-up of 45 months.

Conclusion

Thalidomide may induce long-term remission in laryngeal RDD.

1. Introduction

Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder, commonly seen among children and young adults. It was named after Rosai and Dorfman, who were the first to describe this disease in 1969 [Citation1]. RDD is characterized by massive lymph node enlargement and is sometimes associated with extranodal sites. Laryngeal involvement is relatively rare. Patients with RDD typically exhibit a self-limiting course that requires no treatment. However, the presence of laryngeal involvement may lead to life-threatening airway obstruction that requires effective and durable control of the disease. In this study, we report three cases of laryngeal RDD with excellent response to thalidomide which may give new insight into the treatment of this rare disease.

2. Case report

2.1. Case 1 – thalidomide in a patient who failed chemotherapy and underwent repeated surgical resections

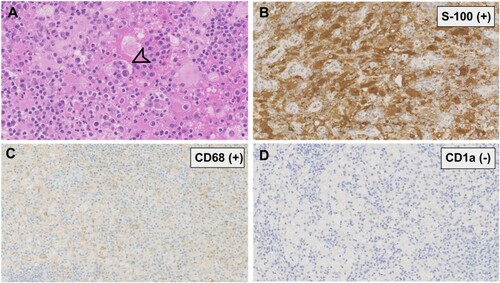

A 39-year-old male who did not have any significant past medical history presented to our outpatient department in 2006 with a two-year history of nasal obstruction. Electronic laryngoscopy revealed multiple submucous nodular lesions located at the nasal septum, the posterior region of the vocal cord, and subglottis. Abnormal laboratory results included an increased erythrocyte sediment rate (ESR) of 60mm/h (normal range, 0–13 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 71 mg/L (normal range, 0–3 mg/L). Surgical resection and biopsy of the nasal mass were performed in December 2006. Microscopic examination showed numerous histiocytes mixed with plasma cells and lymphocytes in the background. The large histiocytes contained abundant pale cytoplasm and exhibited emperipolesis (phagocytosis of lymphocyte or erythrocyte) ((A)). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the histiocytes were S-100, CD68 positive, and CD1a negative ((A–D)). Based on these findings, the diagnosis of RDD was established. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no lymphadenopathy or other organ involvement.

Figure 1. Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings. (A) Histiocytes in the background of plasma cells and lymphocytes, exhibiting abundant pale cytoplasm and emperipolesis (arrow). (HE. original magnification ×400); (B, C) Immunoreactive for S-100, CD68, respectively. (original magnification ×200) (D) Negative for CD1a. (original magnification ×200).

The patient was initially treated with three cycles of cladribine but achieved no response. He developed progressing dyspnea. A second endoscopic resection of the upper respiratory tract lesions was performed to relieve airway obstruction in April 2007. However, the nasopharynx and laryngeal lesions still progressed. Another four endoscopic operations had to be done (in 2008, 2010, 2014, and 2016) and finally, tracheostomy was performed. In September 2016, thalidomide 100 mg/d combined with prednisone 40 mg/d was started. The steroid was slowly tapered and discontinued. After 20 months of treatment, the laryngeal lesions greatly resolved on laryngoscopy examination with normal inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP). Since the patient developed thalidomide-induced peripheral sensory neuropathy, he was switched to lenalidomide 25 mg/d. This patient is still on lenalidomide treatment with no disease progression at his 45-month follow-up visit. Endoscopic surgery is no longer needed after starting thalidomide therapy.

2.2. Case 2 – thalidomide in a young female who failed systemic steroid therapy

A 26-year-old woman was referred to our department complaining of a hoarse voice for one year. Laryngoscopy revealed multiple lesions in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and subglottis. A biopsy of the nasopharynx lesion was performed. Histopathological examination showed numerous large histiocytes with abundant pale cytoplasm. Lymphocytes and plasma cells were seen in the background infiltrate. These histiocytes were positive for S-100 and CD68 and negative for CD1a on immunohistochemical staining which was consistent with RDD. No lymphadenopathy or lesions outside the upper respiratory tract were noticed at diagnosis. The patient was initially treated with prednisone 60 mg/d. However, the laryngeal lesions still exhibited slow progression accompanying by new-onset cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy. She was then treated with thalidomide 100 mg/d. After 10 months of treatment, the cervical lymphadenopathy completely resolved. The upper respiratory tract lesions were stable on the laryngoscopy examination. However, the patient developed amenorrhea 4 months after starting thalidomide treatment (cumulative dose 12 g).

2.3. Case 3 – thalidomide in a patient presented with emergent airway obstruction

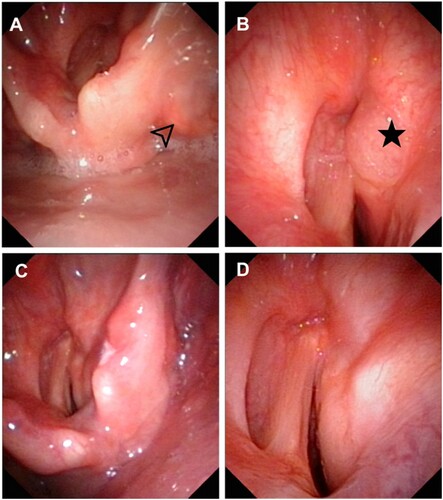

A 24-year-old man presented with complaints of a hoarse voice and progressing dyspnea for five months. His medical history included untreated ankylosing spondylitis for one year. Laryngoscopy revealed lesions located in the pyriform fossa and the anterior region of the ventricular band with mucosal swelling that caused a severe restriction of the right vocal cord and glottic stenosis ((A,B)). A tracheostomy was performed due to emergent airway obstruction. At the same time, a biopsy of the mass was done through the tracheostomy tube. Microscopic examination showed numerous histiocytes and phagocytosed lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical staining of the histiocytes showed positive for S-100 and CD68 and negative for CD1a. Based on these features, a final diagnosis of RDD with laryngeal involvement was established. The patient received thalidomide 100 mg/d as first-line treatment. After 6 months of treatment, there was a notable regression of the laryngeal lesion on the laryngoscopy examination ((C,D)).

Figure 2. Electronic laryngoscopy of the patient in case 3. (A, B) The pretreatment laryngoscopy revealed lesions located in the right pyriform fossa (arrow) and right anterior ventricular band (star) with mucosal swelling and glottic stenosis. (C, D) After six months of thalidomide treatment, laryngoscopy showed notable remission of lesions in the pyriform fossa and ventricular band.

3. Discussion

RDD, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, is a benign non-Langerhans cell histiocytic proliferative disorder that occurs mostly in young adults with a male predominance [Citation2]. RDD typically presents with painless lymphadenopathy associated with fever, night sweats, and fatigue. Extranodal involvement is seen in up to 43% of patients [Citation2]. Common extranodal sites of involvement include the skin, upper respiratory tract, bone, and retro-orbital tissue. The diagnosis of RDD is made based on histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Diagnostic features include the infiltration of large histiocytes with abundant pale cytoplasm and emperipolesis. These histiocytes stain positive for S-100 and CD68 and negative for CD1a on immunohistochemistry analysis [Citation3].

Laryngeal involvement of RDD is relatively rare. A literature search revealed approximately 30 cases in English so far. The largest case series was reported by Niu et al., who reviewed five RDD patients with laryngeal involvement in China [Citation4]. In this study, the main clinical manifestations of laryngeal involvement included hoarse voice and dyspnea. Lesions in the nasal cavity and pharynx were often identified concurrently, suggesting that multiple sites in the upper respiratory tract could be involved. Our case series included three patients with laryngeal RDD. The nasal cavity and pharynx were also involved concurrently.

The exact pathogenesis of RDD is still unknown but is likely multifactorial. Several possible etiologies have been proposed, including viral infections and immunological disorders [Citation5]. Previous studies have associated RDD with viral infections such as Epstein–Barr virus [Citation6] and human herpes virus-6 [Citation7], although a clear link has not been proven. RDD has also been reported in patients with immunological disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus [Citation8], autoimmune hemolytic anemia [Citation9], and IgG4-related disease [Citation10], suggesting a pivotal role of immunity disturbance in the pathogenesis of RDD [Citation5].

RDD is generally considered to be a benign process that is typically self-limiting. However, some patients exhibit episodes of remission and exacerbation that may last for many years. Currently, there is no standard care for RDD. The treatment strategy of RDD should be personalized depending on the clinical presentation, the involvement of vital organs, and prior treatments. Various treatment options, including steroid, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical excision have been reported with variable success [Citation11]. For RDD with laryngeal involvement, surgical excision is the first recommendation both for relieving airway obstruction and also for diagnosis. Medical management after surgical resection is also important to avoid repeated surgery and tracheostomy.

Thalidomide is effective in treating several dermatologic diseases, including cutaneous RDD [Citation12,Citation13]. Moreover, thalidomide was found to be effective in treating cutaneous and low-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis [Citation14,Citation15]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of successful treatment of laryngeal RDD with thalidomide. There are also reports of successful treatment of RDD with lenalidomide which is better tolerated [Citation16]. So why do immunomodulating agents work in RDD? The answer is not precisely known. Previous studies suggested a vital role of immunity disturbance in the pathogenesis of RDD. The efficacy of thalidomide or lenalidomide may be due to their immunomodulatory properties. Besides, thalidomide and lenalidomide could inhibit the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α which are strongly expressed in the lesions of RDD [Citation6,Citation17].

Teratogenic effects and peripheral sensory neuropathy are the most severe adverse effects of thalidomide. Peripheral neuropathy due to thalidomide may be permanent in approximately 50% of patients [Citation18]. Amenorrhea seems to be an under-recognized side-effect of thalidomide [Citation19,Citation20]. In a study conducted by Ordi J et al, amenorrhea appeared four to five months after the beginning of treatment (cumulative dose nine–18g) and the menstrual cycle reappeared two to three months after cessation of thalidomide [Citation20]. The teratogenic effect and drug-related amenorrhea of thalidomide limit its use in young females.

In conclusion, laryngeal involvement is an unusual site of extranodal involvement of RDD that can cause life-threatening airway obstruction. Thalidomide may induce long-term remission in patients after surgical resection and with refractory disease. However, the side-effect of thalidomide such as peripheral neuropathy, teratogenic effect, and amenorrhea should be paid attention to.

Informed consent

Informed written consents were obtained from all patients included in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank MDs Wuyi Li and Fang Qi for the surgeries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87(1):63–70.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease): a review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7(1):19–73.

- Emile J-F, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127(22):2672–2681.

- Niu YY, Li YJ, Wang J, et al. Laryngeal Rosai–Dorfman disease (Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy): a retrospective study of 5 cases. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017(1):1–6.

- Cai Y, Shi Z, Bai Y. Review of Rosai–Dorfman disease: new insights into the pathogenesis of this rare disorder. Acta Haematol. 2017;138(1):14–23.

- Harley EH. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease) in a patient with elevated Epstein-Barr virus titers. J Natl Med Assoc. 1991;83(10):922–924.

- Levine PH, Jahan N, Murari P, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 6 in tissues involved by sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai–Dorfman disease). J Infect Dis. 1992;166(2):291–295.

- Kaur PP, Birbe RC, DeHoratius RJ. Rosai–Dorfman disease in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(5):951–953.

- Grabczynska SA, Toh CT, Francis N, et al. Rosai–Dorfman disease complicated by autoimmune haemolytic anaemia: a case report and review of a multisystem disease with cutaneous infiltrates. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(2):323–326.

- Chen TD, Lee LY. Rosai–Dorfman disease presenting in the parotid gland with features of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(7):705–708.

- Saboo SS, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski KM, et al. Symptomatic extranodal Rosai–Dorfman disease treated with steroids, radiation, and surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):e772–e775.

- Tjiu JW, Hsiao CH, Tsai TF. Cutaneous Rosai–Dorfman disease: remission with thalidomide treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1060–1061.

- Shahidi-Dadras M, Hamedani B, Niknezhad N, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease successfully treated with thalidomide: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(5):e13005.

- Subramaniyan R, Ramachandran R, Rajangam G, et al. Purely cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as an ulcer on the chin in an elderly man successfully treated with thalidomide. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(6):407–409.

- McClain KL, Kozinetz CA. A phase II trial using thalidomide for Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(1):44–49.

- Rubinstein M, Assal A, Scherba M, et al. Lenalidomide in the treatment of Rosai Dorfman disease-a first in use report. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(2): E1.

- Anderson KC. Lenalidomide and thalidomide: mechanisms of action–similarities and differences. Semin Hematol. 2005; 42(4 Suppl 4):S3–S8.

- Tseng S, Pak G, Washenik K, et al. Rediscovering thalidomide: a review of its mechanism of action, side effects, and potential uses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(6):969–979.

- Passeron T, Lacour JP, Murr D, et al. Thalidomide-induced amenorrhoea: two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(6):1292–1293.

- Ordi J, Cortes F, Martinez N, et al. Thalidomide induces amenorrhea in patients with lupus disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(12):2273–2275.