ABSTRACT

Objectives

Immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP) is an ultra-rare life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy affecting adults with unpredictable disease onset and acute presentation. This study aimed to describe the health-related quality of life (HRQoL), cognitive functioning and work productivity of survivors following acute episode(s) of iTTP in the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods

An online survey was developed in collaboration with the TTPNetwork. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the health questionnaire Short Form Survey-36 Version 2 (SF-36v2), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS), the PROMIS Cognitive Function Abilities Subset – Short Form 6a (PROMIS CFAS – SF6a), and the Work Productivity and Activity Index: Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP), along with several iTTP-specific bespoke questions.

Results

Fifty participants were recruited between July-November 2019. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) standardized SF-36v2 physical and mental component scores were 42.16 (9.59) and 33.61 (12.34), lower than population norms. The mean (SD) standardized PROMIS CFAS – SF6a score was 39.69 (7.86), lower than population norms. HADS mean (SD) scores of 12.18 (3.14) and 11.78 (2.36) indicated moderate levels of anxiety and depression, respectively. Of those employed (58%), approximately 42.73% of participants reported work productivity loss due to their iTTP. Participants also reported experiencing flashbacks, fatigue interference in family, social and intimate life, and fears of relapse.

Discussion and conclusion

Regardless of recency of the last acute episode, participant scores signified impairments in all domains. Remission from an acute episode of disease does not signify the conclusion of care, but rather the requirement for long-term healthcare particularly focused on psychological support.

Introduction

Acquired, or immune-mediated, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP), accounting for approximately 95% of all TTP [Citation1], is a life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy affecting adults, with an average diagnosis age of 40 years and a female to male ratio of 3:1 [Citation2–4]. The ultra-rare condition, referred to here on as immune-mediated TTP [Citation5], estimated to affect up to 6 in 1 million people in the UK [Citation6,Citation7], is caused by antibody-mediated depletion of the enzyme ADAMTS13 that cleaves von Willebrand factor multimers, leading to the formation of platelet-rich thrombi in the microcirculation [Citation8]. Platelet consumption in microthrombi leads to thrombocytopenia, tissue ischaemia and organ dysfunction, most commonly in the brain, heart and kidneys, and resulting in early death if untreated [Citation9]. Acute episodes require emergency treatment; however, despite aggressive therapy, acute episode(s) are still associated with mortality risk [Citation10,Citation11]. Survivors of an acute episode are at risk of relapse; [Citation11,Citation12] analysis of 20 years of Oklahoma TTP registry data of adults who received plasma exchange treatment (PEX), estimated that the risk for relapse at 7.5 years was 41% [Citation13].

Evidence is sparse due to the rarity of the condition. Research into the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of people living with iTTP primarily stems from cohort studies in the United States [Citation10,Citation13–15]. Following an acute episode, survivors report various ongoing negative impacts on HRQoL, including activities of daily living, family and social life, physical functioning [Citation14], psychological wellbeing, and cognitive ability [Citation10,Citation11,Citation15,Citation16]. To date, no research has been conducted in the UK drawing on patient perspectives. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are central to understanding the true impact of illness from the patient perspective and to better understand efficacious targets for therapeutic intervention. Borne from discussions with the TTPNetwork, a UK non-profit organization, the purpose of this study was to undertake cross-sectional descriptive analyses of the HRQoL, cognitive function, psychological well-being, and work productivity of UK adults living with iTTP, to better understand the burden of disease and inform health service provision.

Methods and materials

A descriptive cross-sectional study was implemented employing an online survey of adults living with iTTP in the UK.

Survey development

The survey development included patient engagement exercises consistent with recommended good practice [Citation17]. A four-step-process was followed: (1) desk-top review to identify concept elicitation studies investigating HRQoL and functioning in iTTP (January 2019; as expected, the initial search yielded limited findings, and the search was extended to all forms of TTP); (2) concept elicitation exercise with three adults with iTTP, recruited through the TTPNetwork; (3) concept mapping to select relevant PROMs and define bespoke questions; and (4) cognitive debriefing conducted with three UK adults living with iTTP to confirm understanding and relevance of questions.

Data collection

Details of the PROMs incorporated into the survey are available in Supplemental Information 1. In brief, the Short Form-36 version 2 (SF-36v2) has 36 items in eight health domains; two summary subscales define the physical and mental components [Citation18,Citation19]. The PROMIS – Cognitive Function Abilities Subset – Short Form 6a (PROMIS CFAS – SF6a) [Citation20] comprises six items assessing mental acuity, concentration, memory, verbal fluency, and perceived impact on QoL. Higher scores represent better HRQoL and cognitive function. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation21] comprises Anxiety and Depression scales containing seven items each, with scores ranging from 0 to 21 and higher scores indicating more severe symptoms [Citation21]. The Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem (WPAI:SHP) [Citation22] yields four scores expressed as impairment percentages, with higher values indicating worse outcomes: absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity loss (which only apply to employed participants), and overall activity impairment (applying to both employed and unemployed participants). Bespoke questions covered iTTP interference with family, social and intimate life, financial stress, independence, travel, social isolation, verbalizing of thoughts, flashbacks, and fears of relapse.

Ethical approval was received from Salus Institutional Review Board (IRB) (reference: CAB 19/001) and following user testing, the survey was publicized through the TTPNetwork closed Facebook group, available for 12 weeks between July and November 2019, with a target of between 30 and 50 participants. Inclusion criteria were self-reported diagnosis of iTTP; ≥18 years of age at consent; able and willing to complete the online survey and provide written informed consent. Participants were excluded if they were enrolled in the phase 3b post-Hercules prospective study (run by Ablynx/Sanofi) as these participants were already being surveyed using the SF-36 and the authors wished to avoid increasing participant burden. Initially, adults with >12 months since their last acute episode were excluded; however, following discussions with the TTPNetwork, this criterion was removed in recognition of the ongoing impacts regardless of interval since the last acute episode. Participants were categorized according to recency of episode using 12 months as a threshold, in order to explore differences in responses. A shopping voucher was offered to participants in recognition of the time burden.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. The majority of quantitative variables were presented as means (standard deviation [SD] and/or 95% confidence interval [CI]); where data were not normally distributed (i.e. WPAI-SPH), medians (interquartile range and/or range), were reported. Categorical variables were presented as a frequency count and percentage of the total (N [%]).

Standardized scores (US norm-based scoring) were calculated for the SF-36v2 [Citation19] and for the PROMIS CFAS – SF6a [Citation20]. UK norms are unavailable for the PROMIS CFAS – SF6a, although in the case of the SF-36v2, UK and US norms are statistically comparable [Citation23,Citation24], so US norms were employed for consistency. Median scores are presented for the WPAI-SHP due to the large variability in the data. For missing questionnaire data, instructions from developer guidelines were followed; no other imputations were applied. Data were analysed for the total sample and stratified by time since the last episode of iTTP; defined as ‘≤12months_group’ for those whose episode was ≤12months ago and ‘>12months_group’ for those whose episode was >12months ago.

Results

Survey development

The desk-top review identified one iTTP-specific concept-elicitation exercise [Citation25]; no validated TTP-specific PROMs were identified. Additional studies relating to impacts on HRQoL and functioning in people with TTP were identified: four US studies on the TTP-HUS Oklahoma Registry data from adults initiating PEX [Citation14] and one German study [Citation26]. These studies reported on various domains of HRQoL and functioning including depression [Citation10,Citation26], post-traumatic stress [Citation27], cognitive function [Citation16,Citation26] and the overall HRQoL of adults deemed ‘in recovery’ from TTP i.e. 1 year since last PEX [Citation14].

Our patient engagement exercise confirmed the relevance of all concepts from the SF-36v2 except sleep disturbance. Furthermore, participants ratified many of the concepts of importance identified from the previously published concept elicitation exercise [Citation25] and suggested extensions to measure the impacts of fatigue (on social, family and work-life), cognitive difficulties (attention, concentration and the ability to use language), and the experience of flashbacks. Further mapping identified that some of these additional concepts could be captured by alternative PROMs and several optional bespoke questions (see Supplemental information 2). The final survey was assessed by three adults with iTTP who described the questions as ‘easy to understand’ and ‘relevant’, although the total number of items was considered burdensome for individuals early in their diagnosis.

Online survey – PROMs

The survey was completed by 50 participants. A programming error resulted in missing demographic data for 30% of the sample. Of the 35 participants with demographic data available (), the majority were female (n = 34, 97.1%) and in the age categories of 31–50 years (54.3%). The mean (SD) total number of lifetime acute episodes was 2.7 (3.4) (‘≤12months_group’: 3.5 [5.9]; ‘>12months_group’ : 2.4 [1.8]).

Table 1. Participant demographics and characteristics.

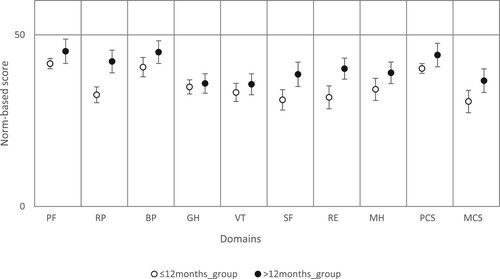

Higher scores on the SF-36v2 and PROMIS CFA – SF6a represent better health states and a mean (SD) of 50 (10) represents the average level of the domain for the US general population. The mean (SD) standardized SF-36v2 scores were 42.16 (9.59) and 33.61 (12.34) for the physical component and mental component, respectively. In addition, mean SF-36v2 domain and component scores stratified by sub-groups are presented in . Participants in the ‘>12months_group’ generally had higher mean scores compared with the ‘≤12months_group’ across SF-36v2 domain and component scores, signifying better HRQoL. The mean (SD) standardized PROMIS CFA – SF6a cognitive function score for the total sample was 39.69 (7.86).

Figure 1. SF-36v2 domains, stratified by recency of last acute episode.

Note: The data represents the mean norm-based scores with the 95% CIs for each of the eight domains of the SF-36 and also for the two component summary measures. Data for each measurement are compared to the mean value for the US population that has been normalized to a mean score of 50, designated by the line.

PF=Physical Functioning; RP=Role Physical; BP=Bodily Pain; GH=General Health; V=Vitality; SF=Social Functioning; RE=Role Emotional; MH=Mental Health; PCS=Physical Component Score; and MCS=mental Component Score.

The two HAD scales range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Mean HADS (SD) scores for the total sample were reported as 12.18 (3.14) (Anxiety) and 11.78 (2.36) (Depression), respectively.

At the time of completing the survey, 29 of 50 (58%) respondents were employed. WPAI:SHP outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity, i.e. worse outcomes. These participants reported 42.73% work productivity loss. General activity impairment due to iTTP was reported as 70%, 80% and 41% for the total sample, ‘≤12months_group’ and ‘>12months_group’ respectively. Scores for all the PROMs stratified by sub-groups are summarized in .

Table 2. Scores for PROMs.

Online survey – bespoke questions

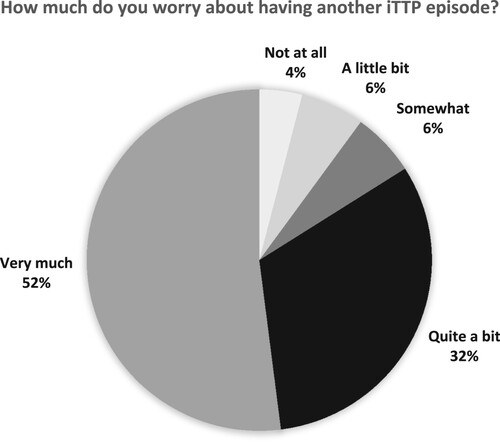

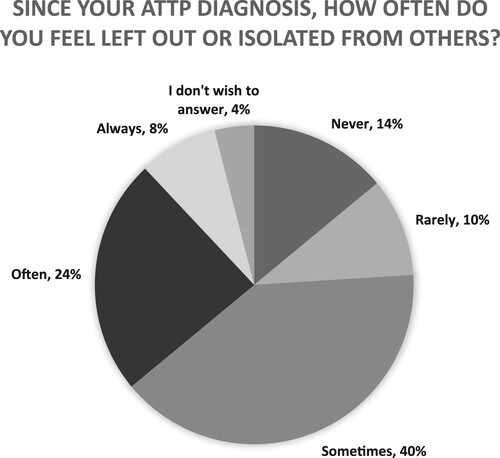

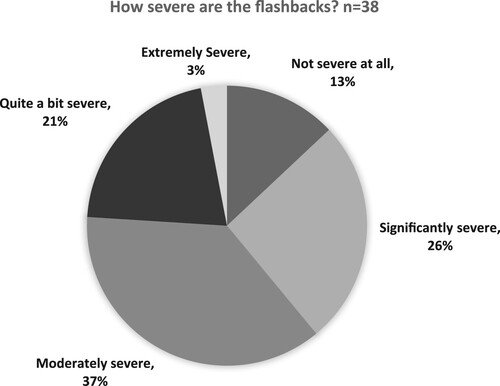

Responses to the bespoke questions are presented for the total sample in and and . Between 64% and 70% of participants reported that iTTP influenced their ability to travel daily, go on holiday, be independent, or their desire/ability to have sex (). Most participants (84%) reported feeling ‘quite a bit’ or ‘very much’ worried about having another acute episode (). A large proportion (≥66%) of participants selected ‘often’ or ‘always’ when asked if fatigue had interfered with their family life, social activities or work within the last 4 weeks (). Thirty-two percent (n = 16) of participants stated they felt left out/isolated ‘often’ or ‘always’, however, 4% of participants chose not to answer this question (). Seventy-six percent (n = 38) of participants stated they had ever suffered flashbacks of an iTTP episode; of these, 61% (n = 23/38) stated the severity was moderate to extremely severe (see ).

Table 3. Bespoke questions – activities of daily living, n = 50.

Table 4. Bespoke questions – fatigue interference, n = 50.

Discussion

Our survey sample was largely female, reflecting the accepted sex distribution of the disease [Citation2], with half experiencing their last acute episode more than 12 months previously. HRQoL, as illustrated by the SF-36v2 component scores and domains, was markedly lower than comparable population norms [Citation23] and lower than the UK population norms for women and those with chronic illnesses [Citation23], irrespective of recency of acute episode. The score for the mental component was more than one SD below that of the US general population [Citation23]. The bespoke questions highlighted the impacts on participants’ ability to go on holiday, be independent, and their desire/ability to have sex. These are all important life impacts that have not been previously assessed in people with iTTP. Furthermore, survey respondents reported high levels of overall work productivity loss similar to those reported in studies of other chronic conditions [Citation28]. Overall, our findings support results from the Oklahoma Registry, which reported HRQoL impairments even when physical examinations and biologic markers suggested haematologic and immunologic remission one year following completion of PEX [Citation14].

Despite the fact neurological signs and symptoms of an acute TTP episode are typically transient and resolve with remission [Citation3], we found that cognitive function was impaired in UK adults with iTTP. Comparison with US data shows that the scores for cognitive function among participants in our survey sample were at least one standard deviation below that of the US general population, irrespective of episode recency. This suggests a notable cognitive dysfunction among our study participants in terms of concentration, sharpness of mind, and difficulties putting thoughts into words. Other studies have shown that the magnitude of cognitive impairments is not associated with the interval from an acute episode, occurrences of relapses [Citation15,Citation16,Citation26], age [Citation16], nor with the occurrence of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (activity <10%) during remission [Citation15]. However, studies differ in their conclusions about the relationship between severe neurologic abnormalities during an acute iTTP episode and subsequent cognitive impairments during remission. Kennedy et al. suggested that deficits in attention, processing speed, and memory may be due to the residual effects of diffuse cerebral microvascular thrombosis, not evidenced in typical clinical neurological assessments [Citation16]. Alwan et al. found an association between self-reported persistent cognitive issues and abnormal cerebral MRI results in TTP survivors, especially in the areas of the brain responsible for executive function. They propose that this is a result of microvascular thrombosis in the acute TTP episode – this has biologic plausibility however the sample size was small [Citation29].

Previous studies have also demonstrated associations between cognitive difficulties and other HRQoL impacts, such as emotional wellbeing and fatigue [Citation16,Citation30]. Although the frequency of tiredness or fatigue features in the SF-36v2 and PROMIS CFAS – SF6a, the participants in our concept elicitation exercise identified the need to ask specifically about the impacts of fatigue. The majority of survey participants reported frequent interference in family, social life, and work. These findings add to previous qualitative research illustrating the inter-relationships between HRQoL concepts; participants described how the inability to do normal activities and socialize led to isolation and feelings of worthlessness, and fear of infection from others led people to self-isolate [Citation31].

Overall, our survey participants met HADS criteria for moderate anxiety and depression, with scores comparable to previous studies in other diseases considered to be similar to iTTP in symptomology (Guillain-Barré syndrome, stroke or sepsis) [Citation32,Citation33]. Evidence suggests that the prevalence of depression among adults with iTTP is much higher than healthy controls [Citation26,Citation31] and European and US population norms [Citation10,Citation15,Citation26,Citation30], after controlling for certain demographics. Alwan et al., also showed that self-reported depression and anxiety existed regardless of neurological symptoms [Citation29]. Due to the nature of our cross-sectional study design, the reports of depression and anxiety cannot be attributed directly to iTTP, as any symptoms prior to diagnosis were unknown. However, in previous qualitative research involving people with iTTP and depression, only 31% reported a mental health diagnosis prior to disease onset, and they described how acute episodes had contributed to psychological distress [Citation31]. Furthermore, it is plausible to assume that the fear of relapsing expressed by a large proportion of our survey respondents would contribute to higher anxiety.

A high prevalence of flashbacks was also reported by the survey respondents, a common feature in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [Citation34]. Another cross-sectional survey of patients with TTP found that approximately one-third screened positive for possible PTSD [Citation27], suggesting patients with iTTP may experience multiple psychological co-morbidities. Adults with iTTP have described the terror and fear of dying during an acute episode and expressed the belief that surviving had changed them mentally and physically, due to fatigue and cognitive difficulties [Citation31]. Researchers have recommended the administration of annual screening for depression and cognitive function among adults who are in remission from iTTP and improved pathways to psychological or pharmacological interventions [Citation15,Citation26], and we argue that this should also include consideration of PTSD. Given the devasting impacts that mental health problems can have on HRQoL, this also suggests the need to reconceptualize recovery from iTTP to one that goes beyond biochemical definitions.

Our study has limitations, some of which are an artefact of iTTP being an ultra-rare condition. These may limit the ability to generalize findings to the broader iTTP population. Although females dominate the patient population in general (75%), they were over-represented in our sample. The online survey was advertised on the closed TTPNetwork Facebook Group; this may have introduced selection bias as only network members and those engaged with online technology were informed about the study. It could also be that only people with more severe ongoing complications may seek out support from the Network. On the other hand, omitting treating centres may have excluded those patients with recent acute episodes of iTTP, who may have been most severely affected. It is also possible that participants in the survey were those whose HRQoL or cognitive function was sufficient to allow them to participate, and they may have been influenced by prior discussions within the Network. As the study was focused on patient perspectives, ascertaining clinical confirmation of iTTP diagnosis was not deemed relevant to the design. In addition, we intended to recruit carers in recognition of the anecdotal evidence that family members are also significantly impacted by the disease. However, recruitment difficulties and survey programming errors made this unfeasible. Our study exhibits strengths in terms of the high completion rate for most questions, limiting non-response bias, as well the collaborative process of survey design, which resulted in the identification of several additional concepts not covered by the generic PROMs.

Conclusion

Impairments in HRQoL, cognitive function, psychological wellbeing and physical functioning were reported across the sample, regardless of recency of acute episodes. These findings add to the evidence that the experience of living with iTTP is akin to that of a chronic disorder rather than one characterized by acute episodes and complete remission [Citation10,Citation14,Citation16]. We support the conclusions of others that remission from an acute episode does not signify the conclusion of care, but rather the requirement for long-term healthcare [Citation8], particularly psychological support. The relevance of the HRQoL concepts covered in the bespoke questions such as fatigue interference, independence, and sexual intimacy point to the value of developing a disease-specific HRQoL measure.

Author contributions

Authors SH, FC & CB designed the study and implemented the data collection. Author ER reviewed the literature and developed the survey. Author LP assisted in conducting data analysis and authors LP & KB interpreted the study data. Author KB wrote the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (109.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level data and related study documents including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Patient-level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Further details on Sanofi’s data-sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barbour T, Johnson S, Cohney S, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy and associated renal disorders. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012 Jul 1;27(7):2673–2685.

- Terrell DR, Williams LA, Vesely SK, et al. The incidence of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome: all patients, idiopathic patients, and patients with severe ADAMTS-13 deficiency. J Thromb Haemost. 2005 Jul 1;3(7):1432–1436.

- Joly BS, Coppo P, Veyradier A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2017 May 25;129(21):2836–2846.

- Patschan D, Witzke O, Dührsen U, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in thrombotic microangiopathies – clinical characteristics, risk factors and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006 Mar 30;21(6):1549–1554.

- Scully M, Cataland S, Coppo P, et al. Consensus on the standardization of terminology in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and related thrombotic microangiopathies. J Thromb Haemost. 2017 Feb;15(2):312–322.

- Scully M, Yarranton H, Liesner R, et al. Regional UK TTP registry: correlation with laboratory ADAMTS 13 analysis and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 2008 Sep;142(5):819–826.

- Sukumar S, Lämmle B, Cataland SR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 2;10(3):536.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2008 Jul 1;112(1):11–18.

- Nichols L, Berg A, Rollins-Raval MA, et al. Cardiac injury is a common postmortem finding in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura patients: is empiric cardiac monitoring and protection needed? Ther Apher Dial. 2015 Feb 1;19(1):87–92.

- Deford CC, Reese JA, Schwartz LH, et al. Multiple major morbidities and increased mortality during long-term follow-up after recovery from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2013 Sep 19;122(12):2023–2029.

- Vesely SK. Life after acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: morbidity, mortality, and risks during pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2015 Jun 19;13(S1):S216–S222.

- Frawley N, Ng AP, Nicholls K, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is associated with a high relapse rate after plasma exchange: a single-centre experience. Intern Med J. 2009 Mar 5;39(1):19–24.

- Hovinga JAK, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, et al. Survival and relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2010 Feb 25;115(8):1500–1511.

- Lewis QF, Lanneau MS, Mathias SD, et al. Long-term deficits in health-related quality of life after recovery from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion (Paris). 2008 Dec 23;49(1):118–124.

- Han B, Page EE, Stewart LM, et al. Depression and cognitive impairment following recovery from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2015 Aug 1;90(8):709–714.

- Kennedy AS, Lewis QF, Scott JG, et al. Cognitive deficits after recovery from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion (Paris. 2009 Jun 1;49(6):1092–1101.

- Harrington RL, Hanna ML, Oehrlein EM, et al. Defining patient engagement in research: results of a systematic review and analysis: report of the ISPOR patient-centered special interest group. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2020;23(6):677–688.

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992 Jun 1;30(6):473–483.

- Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. 3rd ed. Lincoln (RI): QualityMetric, Inc.; 2011.

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 Nov 1;63(11):1179–1194.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun 1;67(6):361–370.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics. 1993 Nov 1;4(5):353–365.

- Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S, et al. Assessment of the SF-36 version 2 in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999 Jan 1;53(1):46–50.

- Ware JE, Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Nov 1;51(11):1167–1170.

- Oladapo A, Ito D, Hibbard C, et al. Development of a patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument for patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Value Health. 2018 May;21(S1):S257.

- Falter T, Schmitt V, Herold S, et al. Depression and cognitive deficits as long-term consequences of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion (Paris). 2017 May 1;57(5):1152–1162.

- Chaturvedi S, Oluwole O, Cataland S, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in survivors of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Thromb Res. 2017 Mar 1;151:51–56.

- Maksymowych WP, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Impact of age, sex, physical function, health-related quality of life, and treatment with Adalimumab on work status and work productivity of patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2010 Feb 1;37(2):385–392.

- Alwan F, Mahdi D, Tayabali S, et al. Cerebral MRI findings predict the risk of cognitive impairment in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol. 2020 Dec;191(5):868–874.

- Riva S, Mancini I, Maino A, et al. Long-term neuropsychological sequelae, emotional wellbeing and quality of life in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 2020 Jul 1;105(7):1957–1962.

- Terrell DR, Tolma EL, Stewart LM, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura patients’ attitudes toward depression management: a qualitative study. Health Sci Rep. 2019 Aug 29;2(11):e136.

- Siegert RJ. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005 Apr 1;76(4):469–475.

- Ayerbe L, Ayis S, Crichton S, et al. The natural history of depression up to 15 years after stroke: the South London Stroke Register. Stroke. 2013 Apr 1;44(4):1105–1110.

- Weathers F, Litz B, Keane T, et al. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [Internet]. 2013. Available from: www.ptsd.va.gov.