ABSTRACT

Background

Sickle cell anaemia affects about 4 million people across the globe, making it an inherited disorder of public health importance. Red cell lysis consequent upon haemoglobin crystallization and repeated sickling leads to anaemia and a baseline strain on haemopoiesis. Vaso-occlusion and haemolysis underlies majority of the chronic complications of sickle cell. We evaluated the clinical and laboratory features observed across the various clinical phenotypes in adult sickle cell disease patients.

Methods

Steady state data collected prospectively in a cohort of adult sickle cell disease patients as out-patients between July 2010 and July 2020. The information included epidemiological, clinical and laboratory data.

Results

About 270 patients were captured in this study (165 males and 105 females). Their ages ranged from 16 to 55 years, with a median age of 25 years. Sixty-eight had leg ulcers, 43 of the males had priapism (erectile dysfunction in 8), 42 had AVN, 31 had nephropathy, 23 had osteomyelitis, 15 had osteoarthritis, 12 had cholelithiasis, 10 had stroke or other neurological impairment, 5 had pulmonary hypertension, while 23 had other complications. Frequency of crisis ranged from 0 to >10/year median of 2. Of the 219 recorded, 148 of the patients had been transfused in the past, while 71 had not.

Conclusion

The prevalence of SLU, AVN, priapism, nephropathy and the other complications of SCD show some variations from other studies. This variation in the clinical parameters across different clinical phenotypes indicates an interplay between age, genetic and environmental factors.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease is a chronic haemolytic disorder due to an inherited abnormality of the beta-globin chain of affected persons with associated intravascular sickling and cumulative end-organ damage. The inheritance can be in the homozygous state (Hb SS) or compound heterozygous state (e.g. Hb SC) [Citation1]. The global prevalence of homozygous sickle cell disease is 112 per 100, 000 live births and varies from 43.12 per 100,000 in Europe to 1125 per 100, 000 in Africa [Citation1]. It is estimated that approximately 300,000 children are born annually with the disease, and the global mortality rate is reported to be 0.64 per 100 years of child observation, with Africa recording the highest rate (7.3 per 100 years of observation) [Citation1]. Improved health care systems in some regions of the world have Improved SCD management with a consequent increase in life expectancy [Citation2]. This has led to the increase in people living beyond their fifth decade and, therefore, a resultant increase in the incidence of the chronic complications of the disease [Citation3,Citation4].

The basic pathology in SCD includes de-oxygenation and polymerization of red cells, causing them to deform and haemolyse, leading to a myriad manifestations from vaso-occlusive crises to more chronic complications like leg ulcers, osteonecrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and renal disease [Citation5–7]. An attempt has been made by some investigators to compartmentalize the complications of SCD in either being haemolytic or vaso-occlusive in origin, though in most cases, a significant overlap seems to be present [Citation8,Citation9]. This may be helpful in mitigating the occurrence of these complications if this can be clearly described.

Several studies have evaluated the various complications of SCD, but an in-depth description in a cohort with similar cultural and social and probably genetic background offers the unique opportunity to describe the associations and characteristics of these various clinical phenotypes. Hence, this study aims to describe clinical phenotypes of SCD among a cohort of Nigerian SCD patients.

Methods

This was a descriptive study carried out at the Adult Sickle Cell Clinic (ASCDC) of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) Enugu involving SCD patients who came for routine follow-up visits. The ASCDC of UNTH runs a weekly outpatient clinic offering a comprehensive care and sees about 20 adult patients per week. The SCD patients come from Enugu state and surrounding town.

Steady-state data was collected prospectively from 270 SCD patients over a period of 10years, between July 2010 and July 2020. The information included epidemiological, clinical and laboratory data. Prior to data collection, ethical consideration was sought and obtained from the University of Nigeria Research and Ethics Committee and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study period. Records of the clinical phenotypes were obtained from patients’ case notes and included patients who had been diagnosed previously with these complications.

Diagnostic criteria are as follows;

Sickle leg ulcers: presence of non-traumatic ulcerations in the lower limb.

Avascular necrosis: presence of clinical and radiological evidence of necrosis of the humeral and or femoral head.

Priapism: presence of sustained, painful and non-stimulated penile erection.

Nephropathy (CKD): presence of persistent albuminuria with or without a glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 ml/h.

Osteomyelitis: presence of clinical and radiological evidence of bone necrosis and infection.

Cholelithaissis: presence of sonological evidence of gall bladder and or bile duct stones.

Data analysis was done using IBM SPSS 25.0 Chicago Illinois. The data is presented as tables and figures, while rates are expressed as median values and confidence intervals. The statistical analysis used was correlations and log-rank tests, and each analysis was 2-tailed with a significant set for r values less than 0.05.

Results

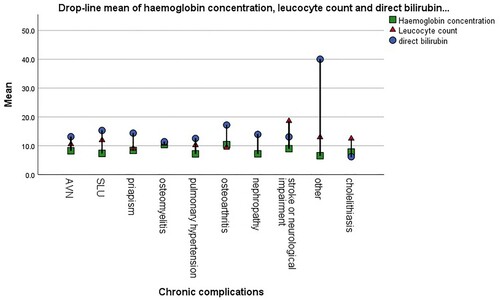

About 270 patients were captured in this study (165 males and 105 females). Their ages ranged from 16 to 55 years, with a median age of 25 years. The median age was 24 for males and 26 for females. shows the laboratory parameters of the patients in this cohort.

Figure 1. Drop-line chart of the mean value of some laboratory variables in adult sickle cell patients.

A total of 68 (51 males and 17 females) had sickle leg ulcers (SLU), giving a prevalence of the leg ulcer to be 25.2% (males 30.9% and females 16.2%). The median age of study participants with leg ulcers was 25 years, haemoglobin concentration (Hb) was 7.5 g/dL, leucocyte count 11.4 × 109/L, platelet count of 347 × 109/L, frequency of crisis was 2 episodes/year and direct bilirubin 8.6 IU/L for leg ulcer patients. The frequency of other chronic complication in patients who had SLU were 19.1% (13/68) AVN, 22.1% (15/68) priapism, 13.2% (9/68) nephropathy, 14.9% (10/68) osteomyelitis and 4.4% (3/68) each for osteoarthritis and neurological complications. There was no significant correlation between the occurrence of SLU and any clinical (frequency of crisis and transfusion) or laboratory (haemoglobin concentration, leukocyte count, platelet count and bilirubin) indicators of severe disease. However, only the male gender had a significant relationship with SLU (4.457, p = .041), while the occurrence of AVN (0.026, p = 0.8980), nephropathy (1.408, p = 0.315), osteomyelitis (0.686, p = 0.482), pulmonary hypertension (3.05, p = 0.159) and cholelithiasis (0.89, p = 1.00), all showed no relationship.

We had a total of 42 (24 males and 18 females) study participants who had avascular necrosis (AVN) with a prevalence of 15.6% (males 14.5% and females 17.1%). This was not significantly associated with sex (1.852, p = 0.058), SLU (0.312, p = 0.589), nephropathy (2.376, p = 0.164), osteomyelitis (1.016, p = 0.418), pulmonary hypertension (0.024, p = 1.00) or cholelithiasis (3.8, p = 0.071). The median age was 26 years, Hb was 8.2 g/dL, leucocyte count 9.9 × 109/L, platelet count of 368 × 109/L, frequency of crisis was 4 episodes/year and direct bilirubin was 8.6 IU/L. The frequency of other chronic complication in patients who had AVN were 31.7% (13/41) SLU, 4.9% (2/41) priapism, 9.8% (4/41) nephropathy, 17.1% (7/41) osteomyelitis, 9.8% (4/41) osteoarthritis and 4.9% (2/41) neurological complications. There was no significant relationship between the occurrence of AVN and the measured indicators of severe disease in this cohort.

Of the 165 male participants, 43 had priapism and 8 had erectile dysfunction. This makes the prevalence of priapism among the adult male SCD patients to be 26.6%. Their median age was 25 years, Hb was 8 g/dL, leucocyte count 10.2 × 109/L, platelet count of 306 × 109/L, frequency of crisis was 7 episodes/year and direct bilirubin 11.8 IU/L. The frequency of other chronic complication in patients who had priapism were; 34.1% (15/44) SLU, 4.8% (2/44) AVN; 2.4% (1/44) nephropathy, 6.8% (3/44) osteomyelitis; 2.4% (1/44) Osteoarthritis and 4.8 (2/44) neurological complications. This complication was significantly associated with the AVN (6.918, p = 0.007) and nephropathy (7.166, p = 0.01) but not with osteomyelitis (1.632, p = 0.249), pulmonary hypertension (1.743, p = 0.3), cholelithiasis (0.474, p = 0.709) or SLU (1.826, p = 0.187).

Thirty-one of the SCD patients under study (15 males and 16 females) had nephropathy, making the prevalence of nephropathy in SCD to be 11.5%% (9% in males and 15.2% in females). Median age was 27 years, Hb was 7.2 g/dL, leucocyte count 11.1 × 109/L, platelet count of 263 × 109/L, frequency of crisis was 2 episodes/year and direct bilirubin 8.6 IU/L in nephropathy. The frequency of other chronic complication in patients who had nephropathy were 34.1% (15/44) SLU, HHH AVN, 3.1% (1/32) priapism, 6.7% (2/44) osteomyelitis, 3.1% (1/44) osteoarthritis and 9.4% (3/44) neurological complications. Kidney disease was significantly associated with the female gender (4.708, p = 0.039) and cholelithiasis (5.14, p = 0.039) but not with osteomyelitis (1.051, p = 0.379), pulmonary hypertension (0.021, p = 1.00), SLU (1.408, p = 0.315) or AVN (1.545, p = 0.221).

Prevalence of osteomyelitis SCD was 8.1% (males 63.6% and females 36.4%). Median age was 24.5 years, Hb was 8.4 g/dL, leucocyte count 10.4 × 109/L, platelet count of 342 × 109/L, frequency of crisis was 2 episodes/year and direct bilirubin 6.67 IU/L in SCD patients with osteomyelitis. The frequency of other chronic complication in patients who had osteomyelitis were; 31.8% (7/22) AVN; 13.6% (3/22) priapism; 45.5% (10/22) SLU; 9.1% (2/22) Osteoarthritis; 4.5% (1/22) neurological complications. There was no significant relationship between this complication and the occurrence of AVN (1.396, p = 0.239), SLU (0.685, p = 0.409), priapism (1.617, p = 0.205), nephropathy (1.052, p = 0.305) and other less common complications (1.582, p = 0.21).

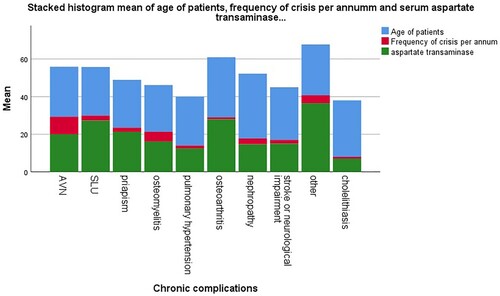

shows the distribution of some demographic and severity indices in the various clinical phenotypes of adult sickle cell patients. While the mean values and frequency of some clinical and laboratory parameters in this group.

Figure 2. Histogram of mean values of some important clinical indicators of disease severity across the various clinical phenotypes.

Table 1. Distribution of some demographic and severity indices in the various clinical phenotypes of adult sickle cell patients.

Discussion

The clinical manifestations or phenotypes of SCD are diverse, and they generally arise from the basic pathogenetic mechanism of vaso-occluion and haemolysis. Variations in these features are dependent on the degree and extent of the interplay of these mechanisms. We studied 270 adults with SCD whose ages ranged up to 55 years which is higher than that reported by Hassan et al. [Citation10], a possible reflection of improvement in health care for our patient cohort [Citation4].

Sickle leg ulcer is one of the vascular complications of SCD resulting from haemolysis, together with priapism and pulmonary hypertension [Citation11]. The prevalence of SLU varies with age, haemoglobin genotype and geographical location. The prevalence of SLU is 25.2% in this study conducted in South East Nigeria, which is similar to that obtained in the nearby south-south region [Citation12] but is higher than that reported in Northern Nigeria (3.1%) [Citation10]. The observed regional differences may be attributable to the already suggested genetic and environmental contributions to the aetiopathogenesis of SLU [Citation13]. Isa et al. also reported a lower prevalence of 6.5% in their study, which included children [Citation7]. While it is rare in people below the age of 10 years [Citation14], the frequency of SLU increases with increasing age after the third decade of life [Citation13]. We studied only adults unlike the work by Isa and colleagues that included children who could have been responsible for the lower prevalence reported. The older the individuals with SCD lived, the more likely they are to have complications of the disease [Citation15]. The median age of study participants with SLU was 26 years with the age range of 16–55 years which is higher than the age range reported by Hassan et al. [Citation10]. This could have contributed to the higher prevalence reported. In this study, SLU is more prevalent in males at a ratio of M:F = 3:1, which is similar to that reported by Bazuaye et al. in Benin Nigeria [Citation11]. Of note is the lower steady-state Hb of these individuals with SLU when compared to the other complications (apart from nephropathy) as well as a higher bilirubin concentration which support SLU being a component of the haemolysis phenotype.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is a notable debilitating complication of SCD. We got a prevalence of 15.6%, which is in keeping with the report by Akinyoola et al. (15.9%) [Citation16] but at variance with that of Adegoke et al. (1.7%), whose study subjects are children [Citation17] and a previous report from the same centre (13.3%). The prevalence of AVN, just as other SCD complications, increases with increasing age [Citation18]. This variation in the prevalence rates could probably be due to the older age range of study participants and a longer period of review in the index study compared to the former [Citation19]. As opposed to a previous report of increasing prevalence with worsening severity of the disease [Citation18], more males had AVN in our study with an M:F ratio of 3:1. Our SCD cohort showed no significant correlation between the occurrence of AVN and the measured indicators of severe disease. This may indicate a multi-faceted pathogenesis in this complication other than vaso-occlusion. However, they had a higher Hb when compared to the Hb in other complications, expectedly being of the vaso occlusive phenotype [Citation18].

Priapism is frequently common in male SCD patients, with a prevalence of 26.6% in our study. This is lower than the reports from two independent Nigerian researchers who reported prevalence rates of 35.0% and 39.1%, respectively, in their questionnaire-based studies [Citation20,Citation21]. Ischaemic priapism is the subtype that is commoner in SCD and it is the subtype associated with more complications [Citation22]. This may explain why up to 4.9% of the male SCD patients in this study already have erectile dysfunction. It may also explain the co-occurrence of priapism with nephropathy and AVN, possibly due to worsened vessel occlusion. Being a complication in the haemolysis-endothelial dysfunction subphenotype [Citation23], it unsurprisingly has a higher steady-state Hb when compared to the other complications in the viscosity-vaso occlusion phenotype. Its prevalence, however, does not show a correlation with features of disease severity, and as such, patients should be evaluated for priapism and erectile dysfunction regardless of disease severity.

Nephropathy in SCD usually starts in childhood as hyposthenuria and may progress to chronic kidney injury, it encompasses the following renal complications: haematuria, hyposthenuria, renal papillary necrosis, proteinuria, renal tubular disorders, glomerulopthy and acute and chronic kidney injury [Citation24,Citation25]. Our study recorded a prevalence of 11.5% for nephropathy. There was a significant relationship between the occurrence of nephropathy and cholelithiasis; this can be explained by the effect of haemoglobinuria secondary to – increasing haemolysis, on the nephrons and formation of bilirubin stones. The mean steady-state Hb and platelet count of the nephropathy cohort are comparatively low. Severe or worsening anaemia is both a cause and effect of chronic kidney injury (CKI) in SCD [Citation26]. Anaemia can result from altered hepcidin metabolism due to inflammation in CKI as well as reduced erythropoietin production seen in CKI [Citation27]. There are reports of reduced platelet production and increase clearance in CKI [Citation26,Citation27]. All these might have contributed to lower Hb and platelet counts seen in individuals with nephropathy. The median age of our study subjects with nephropathy is 27 years. A previous study reported a prevalence CKI of 4.0% for a study cohort with a median age of 23 years and 12% when the review was over a longer period of time, with a median age of study subjects being 37 years [Citation28], This shows that the prevalence equally increases with increasing age. The occurrence of nephropathy was also found to be unrelated to severe sickle cell disease. This implies that screening for this complication should not be limited to people with severe sickle cell symptoms.

Osteomyelitis is a relatively common complication of SCD occurring due to the compromised immunity from impaired leucocyte and complement function, hyposplenism, and bone necrosis [Citation29]. It is a frequent cause of bone pain and hospital presentation [Citation30]. The prevalence as obtained from this study is 8.1%, with a median age of occurrence of 24.5 years which is the least when compared to other complications. Osteomyelitis is known to be commoner in children, which explains why we have a lower median age. There are variable reports of gender predilection of osteomyelitis in SCD, while some reported lower incidence in males, some reported higher prevalence, and others reported equal distribution [Citation31–33]. In this study, males were more likely to present with osteomyelitis than females (M:F = 1.8:1). The gender variation could be a result of age and sample size differences. There was no relationship between osteomyelitis and the other complications of SCD, and this may be due to the predominance of an infective pathogenesis in the occurrence of this complication. Osteoarthritis is one of the major osteoarticular complications of SCD; it can be inflammatory or non-inflammatory [Citation34]. We reported a prevalence of 4.4% in our SCD cohort, which is less than what was documented in previous studies [Citation35,Citation36]. This is probably due to the nature of the study subjects. Osteoarthritis is thought to be commoner among the paediatric age group, we conducted our research on the adult population with a median age of 26 years. Just as was previously reported [Citation32], we found males to be more affected than females.

Stroke and other neurological complications of SCD are significant but preventable causes of disability and reduced quality of life. We got a prevalence of 3.7% which is similar to that obtained in the same centre in an earlier study (3.37%) [Citation37] but at variance, with a another study carried out in the same centre but on a younger patient population (2.25%) and a multicenter Nigerian study (1.24%) [Citation37]. These differences may be attributed to differences in age as well as environmental and genetic composition present in the different regions respectively [Citation37].

Pulmonary hypertension is an often overlooked but notable cause of morbidity and mortality in SCD. Its incidence is thought to increase with increasing age. In our study population of adult SCD patients, we recorded a prevalence of 1.85% which is lower than reports from the South-West (3.3%) and northern Nigeria (25.0%) [Citation38,Citation39]. Again, the differences may be explained by selection bias [Citation38] and contributions of socioeconomic, genetic and environmental factors to phenotypic expression of the disease [Citation37,Citation38].

SCD patients also present with different hepatobiliary complications which arise directly from the disease itself or indirectly from its management [Citation40]. They may have repeated hepatic ischaemic injury from repeated VOC leading to hepatic fibrosis and then cholelithiasis arising from chronic haemolysis of red cells [Citation40,Citation41]. On the other hand, they may also have viral infections and iron overload from repeated or chronic transfusion, which directly damages the liver [Citation40]. Clinically, some may be asymptomatic, a few may mimic the common VOC, or may be masked and sometimes missed [Citation42]. Prevalence of cholelithiasis in this study is 4.4% which is lower than previous other reports from Nigeria (10–24.2%) [Citation40,Citation41]. Even though it is a common complication of SCD, it often presents in its asymptomatic form in a majority of cases and as such may sometimes be missed [Citation40,Citation41]. Additionally, dietary factors and diagnostic means may contribute to the observed differences [Citation40]. Since it results from chronic haemolytic processes, its prevalence increases with increasing age [Citation40]. The median age of our study participants is 27 years, and males were found to be two times more susceptible to developing cholelithiasis than females in this study. Other clinical phenotypes presented by our patients include septic arthritis, cephal haematoma, stroke and submental neuropathy, but occur in lesser frequencies.

In summary, the prevalence of SLU, AVN, priapism, nephropathy and the other complications of SCD show some variations from other studies. This variation in the clinical parameters across different clinical phenotypes indicates an interplay between age, genetic and environmental factors and which of the basic pathophysiologic mechanisms predominates.

Conclusion

There are variations in prevalence of the chronic complications of SCD across the different sexes and the findings of previous studies. The co-occurrence of some complications may indicate a common pathogenetic pathway of either haemolysis or vaso-occlussion. The non-significant association of AVN, priapism and SLU indicates a multi-factorial aetiologic background in the causation of these complications.

We, therefore, recommend that our SCD patients be monitored closely and screened for the complications early enough, irrespective of their age and whether they have severe disease or not. Furthermore, there is a need for large nationwide studies to evaluate the impact of care rendered to our patients on the disease morbidity and mortality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Wastnedge E, Waters D, Patel A, et al. The global burden of sickle cell disease in children under five years of age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2018;8:021103.

- Hulihan M, Hassell KL, Raphael JL, et al. CDC grand rounds: improving the lives of persons with sickle cell disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1269–1271.

- Ladu AI, Abba AM, Ogunfemi MK, et al. Prevalence of chronic complications among adults with sickle cell anaemia attending a tertiary hospital in North Eastern Nigeria. J Hematol Hemother. 2020;5:007.

- Makani J, Williams TN, Marsh K. Sickle cell disease in Africa: burden and research priorities. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2017;101:3–14.

- Saraf SL, Molokie RE, Nouraie M, et al. Differences in the clinical and genetypic presentation of sickle cell disease around the world. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2014;15:4–12.

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle cell disease. Lancet. 2010;11:2018–2031.

- Isa H, Adegoke S, Madu A, et al. Sickle cell disease clinical phenotypes in Nigeria: a preliminary analysis of the sickle cell Pan Africa research Consortium Nigeria database. Blood Cell Mol Disease. 2020;84:102438.

- Alexander N, Higgs D, Dover G, et al. Are there clinical phenotypes of homozygous sickle cell disease? Br J Haematol. 2004;126:606–611.

- Gladwin M. Unraveling the haemolytic subphenotypes of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2005;106:2925–2926.

- Hassan A, Gayus DL, Abdulralsheed I, et al. Chronic leg ulcers in sikle cell disease patients in Zaria, Nigeria. Arch Int Surg. 2014;4:141–145.

- Taylor JG, Nolann VG, Kato GJ, et al. The hyperhaemolysis phenotype in sickle cell anaemia: increased risk of leg ulcers, priapism, pulmonary hypertension and death with decreased risk of vasoocclisive events. Blood. 2006;108:787–e2095. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002095.

- Bazuaye GN, Nwannadi AI, Olayemi EE. Leg ulcers in adult sickle cell disease patients in Benin city Nigeria. Gomal J Med Sciences. 2010;8:190–193.

- Ofosu MD, Castro O, Alarif L. Sickle cell leg ulcers are associated with HLA-B35 and CW4. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:482–484.

- Minniti CP, Eckman J, Sebastiani P, et al. Leg ulcers in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:831–833.

- Singh AP, Minniti CP. Leg ulceration in sickle cell disease: an early and visible sign of end organ disease. Sickle Cell Disease - Pain and Common Chronic Complications, Baba Psalm Duniya Inusa, IntechOpen, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5772/64234. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/sickle-cell-disease-pain-and-common-chronic-complications/leg-ulceration-in-sickle-cell-disease-an-early-and-visible-sign-of-end-organ-disease.

- Akinyoola AL, Adediran IA, Asaleye CM. Avascular necrosis of femoral head in sickle cell disease in Nigeria: a retrospective study. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2007;14:217–220.

- Adegoke SA, Adeodu OO, Adekile AD. Sickle cell disease clinical phenotypes in children from south western Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18:95–101.

- Adesina O, Brunson A, Keegan THM, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head in sickle cell disease: prevalence, comorbidities, and surgical outcomes in California. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1287–1295.

- Madu AJ, Madu AK, Umar GK, et al. Avascular necrosis in sickle cell (homozygous S) patients: predictive clinical and laboratory indices. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:86–89.

- Adeyoju AB AB, Olujohungbe AB, Morris J, et al. Priapism in sickle-cell disease; incidence, risk factors and complications-an international multicentre study. BJU Int. 2002;90:898–802.

- Adediran A, Wright K, Akinbami A, et al. Prevalence of priapism and its awareness amongst male homozygous sickle cell patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Advances in Urology. 2013. Article ID 890328.

- Cherian J, Rao AR, Thwaini A, et al. Medical and surgical management of priapism. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:89–94.

- Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Deconstructing sickle cell disease: reappraisal of the role of haemolysis in the development of clinical subphenotypes. Blood Rev. 2007;27:37–47.

- Powars DR, Hiti A, Ramicone E, et al. Outcome in hemoglobin SC disease: a four-decade observational study of clinical, hematologic, and genetic factors. Am J Hematol. 2002 Jul;70(3):206–215.

- Madu A, Galadincci N, Umar G, et al. is renal medullary carcinoma the seventh nephropathy in sickle cell disease: a multicenter Nigerian survey. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:490–496.

- Nath KA, Hebbel RP. Sickle cell disease: renal manifestations and mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:161–171.

- Berns JS. Haematologic complications of chronic kidney disease: erythrocytes and platelets. In: Kimmel PL, Rosenberg ME, editors. Chronic renal disease. Oxford, UK: Academic Press; 2015. 22: p. 266–276.

- Powers DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, et al. Outcome of sickle cell anaemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:363–376.

- Chambers JB, Forsyth DA, Bertrand SL, et al. Retrospective review of osteoarticular infections in a pediatric sickle cell age group. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:682–685.

- Orimolade AE, Oluwadiya KS, Salawu L, et al. A comparison of chronic osteomyelitis in sickle cell disease and non-sickle cell disease patients. Niger J Orthopaed Trauma. 2009;8:11–14.

- Ogunlade SO, Omololu AB, Alonge TO. Acute osteomyelitis in children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Is surgical decompression necessary? Afr J Biochem Res. 2004;7(3):119–123.

- Ebong WW. Acute osteomyelitis in Nigerians with sickle cell disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986;45:911–915.

- Chinawa JM, Chukwu BF, Ikefina AN, et al. Musculoskeletal complications among children with sickle cell anaemia admitted in University of NigeriaTeaching Hospital Ituku- Ozalla Enugu: a 58 month review. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:564–567.

- Schumacher HR, Dorwart BB, Bond J, et al. Chronic synovitis with early cartilage destruction in sickle cell disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1977;36:413–419.

- Agossou-Voyèmè A-K. Epidemiology of the serious hip disorders in children in Benin: prospective study of 180 cases over a 7 years period. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2001;87:539–543.

- Chen CH, Lee ZL, Yang WE, et al. Acute septic arthritis of the hip in children – clinical analyses of 31 cases. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1993;16:239–245.

- Madu AJ, Galadincci NA, Aisha AM, et al. Stroke prevalence amongst sickle cell disease patients in Nigeria: a multicenter study. Afr Health Sci. 2014;16:446–452.

- Dosunmu AO, Balogun TM, Adeyeye OO, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell anamia patients of a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2014;55:161–165.

- Zakari YA, Gordeuk V, Sachdev V, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pulmonary artery hypertension among sickle cell disease patients in Nigeria. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:485–490.

- Kesen RM, Goldberg MF, Lutty GA, et al. Beyond the definitions of the phenotypic complications of sickle cell disease: an update on management. Sci World J. 2013. Article ID 861251, 1, 2013. doi:10.1155.2013.861251.

- Walker TM, Hambleton IR, Serjeant GR. Gallstones in sickle cell disease: observations from the Jamaican cohort study. J Pediatr. 2000;136:80–85.

- Currò G, Meo A, Ippolito D, et al. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis in children with sickle cell disease: early or delayed cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;245:126–129.