ABSTRACT

Objectives

To assess the concordance between lymphoma diagnoses made via tissue biopsy by local pathologists and also to assess the after review of these specimens by more specialized hematopathologists.

Methods

A prospective, non-interventional and multicenter study was conducted at seven sites in Mexico from January 2017 to October 2017. Eligible biopsies were sampled from patients with a previous diagnosis of lymphoma on lymph node biopsy or a diagnosis of extranodal lymphoma, with adequate amount and tissue preservation for the review analysis. The biopsy tissues reviewed by local pathologists were also reviewed by hematopathologists participating in the study. The concordance in diagnosis results was classified into three categories: diagnostic agreement, minor discrepancy and major discrepancy.

Results

Out of 111 samples received, 105 samples met the eligibility criteria and were included for full analysis. The median patient age (range) was 54 (16–94) years. A diagnostic agreement was observed in 23 (21.9%) biopsies, minor discrepancies were observed in 32 (30.5%) biopsies and major discrepancies were observed in 50 (47.6%) biopsies. Diagnostic concordance varied across the seven study sites; the rate of major discrepancies ranged from 0% to 100% and the rate of diagnostic agreement ranged from 0% to 81.8%. Out of the 105 reviewed biopsies, a total of 89 cases were diagnosed as lymphoma by hematopathologists.

Conclusions

This study showed that major discrepancies were observed following the review by hematopathologists compared with that of the local pathologist’s initial diagnosis in nearly one-half cases. In addition, there was a wide variation in the percentage of diagnostic agreements and discrepancies among different study sites.

Introduction

The adequate medical management of patients with hematological neoplasms requires a thorough and accurate histopathological diagnosis. In 1994, the Revised European American Classification of Lymphomas proposed the incorporation of objective criteria, such as morphology, clinical picture and immunophenotype, as well as genetic alterations and the proposal of a cell of origin in the consideration of a diagnosis [Citation1]. Later, in 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) made an effort to order the necessary parameters to establish an adequate and reproducible histopathological diagnosis that allowed the evaluation of the results of treatments in patients with lymphoproliferative neoplasms. This WHO guideline was further updated in 2008 and then in 2016 [Citation2–4]. As a result of such evolutions in clinical diagnosis guidelines, the histological interpretation of lymph nodes and neoplasms of lymphoid origin by pathologists who have not undergone specific training in hematopathology has become increasingly complex. The updated WHO classification emphasizes the importance of evaluating morphology, immunophenotype, genetic and molecular characteristics while considering a lymphoproliferative diagnosis. Furthermore, confusions can arise between the definitions of terminology used in the current version of WHO guidelines and of those in the previous versions of the classification system [Citation3,Citation4]. The appropriate medical management of patients with hematological malignancies is based on the adequate histopathological diagnosis, because therapeutic strategies may vary among different subtypes. Results of incomplete or incorrect diagnosis in inadequate patient treatment increase the risk of a suboptimal response that is caused by either under-treatment or over-treatment.

Critical errors in diagnosis and in common situations that favor a diagnostic error have been discussed in other publications [Citation5]. A category of error recognized in the practice of anatomic pathology is a cognitive error; this might be caused by a lack of knowledge, oversight, misinterpretation, violation of established diagnostic rules or contextual biases. This can lead to insufficient use of antibodies used to aid diagnosis, incomplete knowledge of the staining pattern of various markers of normal lymphoid tissue and lymphomas, or of antibody specificity. As a result, the cognitive error makes diagnosis and treatment difficult for most practitioners [Citation6].

In recent decades, hematopathology has been one of the branches of pathology that has advanced the most in diagnostic techniques, with more specific and sensitive immunohistochemical antibodies. The discrepancy between the initial diagnosis issued by a general pathologist and the revision of the said diagnosis by a hematopathologist, both evaluating the same material, has been reported to range from 5.8% to 60% [Citation7]. However, there has been a paucity of data on the level of concordance between pathologists and hematopathologists while diagnosing lymphoma and its subtypes in different institutional settings in Latin America.

Methods

This was a prospective, non-interventional, multicenter study conducted at seven sites in México from January 2017 to October 2017. The study sites were a mixture of private and public hospitals, including only one teaching hospital. These sites were selected based on their ability to collect and send the study samples and their agreement to provide the needed information per study protocol. Eligible biopsy samples were from patients with diagnosis of lymphoma on lymph node biopsy or a diagnosis of extra nodal lymphoma, made by local pathologists with adequate tissue preservation and amount of tissue for the review analysis. Patients receiving either chemotherapy or corticosteroids before sampling of tissue biopsies were excluded.

Local pathologists from the seven study sites and three hematopathologists, who had completed additional sub-specialty training (between 2 and 3 years fellowship at hematopathology reference hospitals), participated in the study. The same biopsy tissues reviewed by the local pathologists were also sent to one of the three participating hematopathologists. Physicians responsible for treatment decision-making were asked to provide information on patient’s age, gender, type of health institutions (e.g. public or private), medical summary, as well as the report obtained from the pathology evaluation, number of immunohistochemical markers and treatment chosen for the patient with the biopsy reports. The information was collected from initial clinical forms, which included patient’s demographic and biopsy data, haematopathologist reports and a final report from the treating physician including their feedback on changes to treatment decisions. Data were recorded in electronic case report forms. An informed consent was obtained from each participant in the study.

The concordance in diagnosis results was classified into three categories:

Diagnostic agreement: if the diagnoses of local pathologist and hematopathologist concurred.

Minor discrepancy: if there was a difference in the diagnosis but it did not change the treatment decision.

Major discrepancy: if there was a difference in the diagnosis that changed treatment decisions based on guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

Results were characterized using descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency (medians) and spread (range) for continuous variables (e.g. age), and frequency distributions for categorical variables (e.g. gender and diagnosis concordance).

Results

Summary of patient and biopsy characteristics

Out of 111 samples received, 105 samples met the eligibility criteria for full analysis. The median patient age was 54 years (range 16–94) and 57 were females (54.3%). Recruitment was evenly balanced while comparing treatment settings; 52 (49.5%) patients were managed in public health institutions.

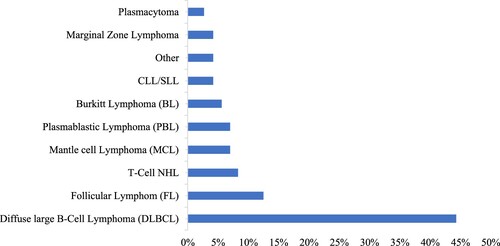

From the 105 biopsies included in the full analysis, 89 were lymphoma cases identified by the hematopathologists, including 17 Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) cases and 72 non-HL cases. The remaining 16 cases included 13 reactive lymphoid proliferation cases, 2 myeloid neoplasm cases and 1 hepatocarcinoma case. illustrates a breakdown of the hematopathologist diagnosis of Non Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) by subtypes. Hematopathologists reported more immunohistochemical disease markers per tissue specimen with a median of 8.7 (3–20) and a mode of 8 compared to local pathologist who reported a median of 5 (0–20) and a mode of 0.

Overall diagnostic concordance

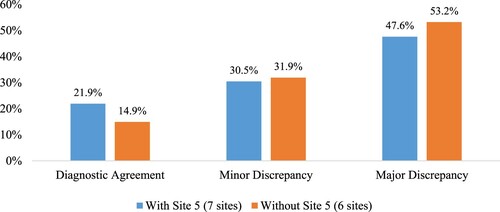

Diagnostic agreement was observed in only 21.9% (n = 23) of the biopsies (). Lymphoma subtypes that the pathologists most commonly found in diagnostic agreement were Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) (8; 34.8%) and HL (6; 26.1%). Minor discrepancies were seen in 30.5% (n = 32) of the biopsies and major discrepancies were observed in almost half of the biopsies 47.6% (n = 50).

Table 1. Biopsy cases with diagnostic agreement by lymphoma subtypes.

The major discrepancies were further categorized into three groups: (1) Ambiguity or lack of full diagnosis (54%; 27/50); (2) change from malignant lesion to benign lesion (22%; 11/50) and (3) change in the type of neoplasm (24%; 12/50).

Diagnostic concordance across the seven study sites

Diagnostic concordance varied across the seven study sites: the rate of major discrepancies ranged from 0% to 100% and the rate of diagnostic agreement ranged from 0% to 81.8% (). Site 5 was the only site where the local pathologist had previously received formal training in hematopathology; this site had the highest rate of diagnostic agreement (81.8%; 9/11) and contributed to the highest number of cases with diagnostic agreement (39.1%; 9/23). If biopsy samples from this site were excluded, diagnostic concordance across the remaining study sites was as follows: 14.9% (14/94) with diagnostic agreement, 31.9% (30/94) with minor discrepancies and 53.2% (50/94) with major discrepancies ().

Table 2. Diagnostic concordance by study sites.

Diagnostic concordance in DLBCL cases

A total of 32 DLBCL cases were diagnosed by hematopathologists, accounting for 44.4% (32/72) of the total NHL cases. Diagnostic concordance for the DLBCL cases was 25% (8/32) with diagnostic agreement, 40.6% (13/32) with minor discrepancies and 34.4% (11/32) with major discrepancies. lists the comparison between diagnosis from local pathologists and the hematopathologists for cases with major discrepancies. In particular, there were five cases of double or triple expressor DLBCL (not confirmed as Double or Triple Hit by FISH), which were not specified in the initial diagnosis by the local pathologists. While Cases 4, 6, 8 and 10 were all diagnosed as DLBCL by local pathologists, etoposide was added for Cases 4, 8 and 10, and treatment for Case 6 was changed from Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin hydrochloride, Vincristine and Prednisone (R-CHOP) to Gemcitabine-Oxaliplatin plus Rituximab (GEMOX-R). In follicular lymphoma (FL), a major discrepancy was observed in four cases: two FL Grade III cases changed to FL Grade II, one FL Grade II case changed to FL Grade III and one FL case without a grade reported was changed to FL Grade II.

Table 3. Major discrepancies in DLBCL cases.

Diagnostic concordance in HL cases

HL was the second most common type of lymphoma diagnosed in this study. There were 17 cases of HL accounting for 18.5% of the total lymphoma cases. Diagnostic concordance for the HL cases was 35.3% (6/17) with diagnostic agreements, 35.3% (6/17) with minor discrepancies and 29.4% (5/17) with major discrepancies. lists the major discrepancies in diagnosis between the local pathologists and hematopathologists.

Table 4. Major discrepancies in HL cases.

Discussion

Appropriate medical management of patients with hematological neoplasms requires the correct histopathological diagnosis. The finding of this study indicates that major discrepancies, which by definition would result in a change of treatment plan as defined by NCCN guidelines, between the local pathologists’ diagnosis and that of the reviewing hematopathologist were observed in nearly one-half (47.6%) of cases. This finding is consistent with reports from other countries and a retrospective report from a single site in Mexico [Citation8,Citation9]. Furthermore, pathology reports from local pathologists may have contained unclear nomenclature and may have relied on terminology from older classifications of lymphoproliferative neoplasms that did not provide guidance for decision-making in a clinical context.

A wide variation in the percentage of diagnostic agreements and discrepancies was observed among different study sites. Notably, a lower rate of diagnostic discrepancy was identified at the Study Site 5 where the local pathologist had received formal training in hematopathology compared to sites where local pathologists had not completed such training. Additionally, no major discrepancies were identified at Study Site 7, a university facility. This aligns with the observations of the previous studies that academic study centers contribute a low rate of discrepancy in the diagnosis of lymphoproliferative neoplasms [Citation10].

In the current study, no cases of DLBCL were characterized as double or triple expressor in the initial evaluation by the local pathologists. However subsequently, hematopathologists identified five such cases. This is important because international treatment guidelines recognize that the subpopulation of DLBCL patients who are double and triple hit (in our cases this was only evaluated by immunohistochemical markers and defined as double or triple expressor) have a lower response rate to conventional R-CHOP treatment, and should therefore receive a more aggressive treatment regime than the typical R-CHOP [Citation11].

The results of this study support findings from previous studies, suggesting that if additional hematopathology training is completed, the diagnostic accuracy is improved. Therefore, it is crucial to establish the hematopahology review as a standard of care for all lymphoma patients, in order to give them the best treatment option based on international clinical guidelines. The Training Protocols of Hematopathology in Mexico includes a full-time 2-year fellowship in a hematology reference hospital such as Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INCan) or Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (INCMNSZ).

The results, however, should be interpreted with caution. Study sites included in this study were based on their ability to collect and send the study samples and relevant information based on study protocol, and thus may be associated with the selection bias toward sites with more advanced clinical practice management. The selection of study sites may underestimate the discrepancy in lymphoma diagnosis in clinics with less advanced clinical practices. Hence, observations in the participating sites may not be generalizable at country level.

Conclusions

This study showed that physicians from the seven study sites in Mexico changed their original treatment decisions that were initially based on local pathologist’s diagnosis in nearly one-half (47.6%) cases after they reviewed the hematopathologist’s diagnosis. There was a wide variation in the percentage of diagnostic agreements and discrepancies among different study sites, where sites with more experienced pathologists demonstrated a lower rate of diagnosis discrepancies in the diagnosis of lymphoma.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Harald S. A revised European–American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84(5):1361–1392.

- Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Geneva Switzerland: WHO Press; 2008.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The updated who classification of hematological malignancies. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. 2018;127(20):2375–2391. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569.

- Harris N, Jaffe E, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting – Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. DOI:JCO.1999.17.12.3835.

- Chan K, Kwong Y. Common misdiagnoses in lymphomas and avoidance strategies. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(6):579–588. DOI:S1470-2045(09)70351-1.

- Tomaszewski JE, Bear HD, Connally JA, et al. Consensus conference on second opinions in diagnostic anatomic pathology: who, what, and when. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114(3):329–335. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/114.3.329.

- LaCasce AS, Kho ME, Friedberg JW, et al. Comparison of referring and final pathology for patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the national comprehensive cancer network. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(31):5107–5112. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4061.

- Chang C, Huang S, Su I, et al. Hematopathologic discrepancies between referral and review diagnoses: a gap between general pathologists and hematopathologists. 2014;55(July 2013):1023–1030. DOI:https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2013.831849.

- Solano-genesta M, Lome-maldonado C, Quezada-fiallos M, et al. Discrepancies in the diagnosis of lymphoproliferative neoplasias. A need for change. Med Univ. 2017;19(74):13–18. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmu.2017.02.002.

- Bowen JM, Perry AM, Laurini JA, et al. Lymphoma diagnosis at an academic centre: rate of revision and impact on patient care. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(2):202–208. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12880.

- Petrich AM, Gandhi M, Jovanovic B, et al. Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis. 2018;124(15):2354–2362. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-578963.A.M.P.