ABSTRACT

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the antiemetic efficacy of a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist (5-HT3RA), ondansetron, in patients with malignant lymphoma receiving multi-day cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy.

Methods

We conducted a single-institution retrospective analysis of patients receiving the first course of an ESHAP (etoposide, cisplatin, methylprednisolone, cytarabine) regimen including 4-day continuous infusion of cisplatin (25 mg/m2/day). All patients received ondansetron 4 mg intravenously during 5-day administration of ESHAP. The primary endpoint was complete response (CR) for emesis, which was defined as absence of both emesis and rescue medications. Total control (TC) was defined as an absence of emetic episodes, including nausea and emesis, and complete protection (CP) was defined as an absence of emesis with addition of rescue antiemetics. Nausea and vomiting were assessed and graded daily by medical staff.

Results

Eighty-two patients were analyzed. Nausea and vomiting were generally well controlled, with the CR rates of emesis being 79% in the overall phase, 82% in the early phase (days 1–6), and 89% in the delayed phase (days 7–10). TC and CP were achieved in 51 patients (62%) and 77 patients (94%) in the overall phase.

Discussion

Most of the chemotherapy regimens for lymphoid malignancies include high-dose corticosteroid which may be also effective as antiemetics. Although NK1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) is generally recommended for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy, it can interact with variety drugs.

Conclusion

Although NK1RA is generally recommended for cisplatin-containing regimen, our results suggest that ondansetron effectively controlled emesis in patients receiving ESHAP therapy which includes high-dose corticosteroid.

Introduction

It is important to maintain treatment intensity and maximize efficacy while minimizing distress in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is the most common adverse effect, and proper management of CINV is essential [Citation1–3]. Cisplatin has been widely used for a variety of cancer chemotherapies. In the guidelines for CINV, cisplatin is classified as a high-emetic-risk antineoplastic agent, and several agents – i.e. NK1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA), dexamethasone and 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist (5-HT3RA) – are recommended for use with cisplatin [Citation4–6]. Although the guidelines separately assess and classify the emetic risk of each anticancer agent, the emetic risk for regimens that combine multiple anticancer agents has not been fully evaluated. The ESHAP regimen consists of multi-day cisplatin (25 mg/m2/day for 4 days) along with etoposide, methylprednisolone and cytarabine, and is the salvage chemotherapy regimen commonly used for refractory or relapsed lymphoid malignancies [Citation7,Citation8]. The ESHAP regimen contains a high-dose of the steroid methylprednisolone (500 mg/day), which often induces antiemetic effects [Citation9,Citation10], and the guidelines do not specify whether NK1RA is needed as an additional antiemetic.

In this study, therefore, to clarify the optimal antiemetics for the ESHAP regimen, we retrospectively evaluated the antiemetic efficacy of a 5-HT3RA, ondansetron, without NK1RA supplementation in patients administered an ESHAP regimen.

Materials and methods

Patients and treatments

This retrospective single-institution analysis was designed to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron alone for the prevention of CINV induced by an ESHAP regimen. Patients who received the first course of a ESHAP ± rituximab regimen for relapsed lymphoid malignancies from January 2012 to April 2019 at Keio University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) were enrolled in the analysis. Patients who received prophylactic aprepitant (n = 3) or whose emetic episodes had not been assessed by medical staff (n = 8) were excluded.

The regimen of ESHAP included etoposide 40 mg/m2/day as a 1 h intravenous infusion from days 1 to 4, cisplatin 25 mg/m2/day as a continuous infusion from days 2 to 5, methylprednisolone 500 mg/day as a 15 min intravenous infusion from days 1 to 5 and cytarabine 2000mg/m2/day given as a 3 h intravenous infusion on day 5 (). The dose of ESHAP was reduced at the discretion of each physician, mostly depending on patient age and comorbidities. All patients received an antiemetic regimen consisting of intravenous ondansetron at a dose of 4 mg every 24 h on days 1–5. Rituximab was added in patients with B-cell lymphoma.

Table 1. Treatment schedule.

Rescue medications, such as metoclopramide and chlorpromazine, were given for the treatment of nausea and vomiting at the discretion of each physician. No additional doses of 5-HT3RA were given during the acute or delayed treatment periods.

All data regarding patient characteristics and records on nausea and vomiting were collected from the institutional database and medical records by physicians and nurses. Nausea and vomiting were assessed daily by medical staff and graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0. This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of Keio University School of Medicine.

Definitions

The primary endpoint of this study was complete response (CR) for emesis, which was defined as an absence of both emesis and rescue medications. In addition, total control (TC) was defined as an absence of emetic episodes, including nausea and emesis, without rescue medications [Citation11], and complete protection (CP) was defined as absence of emesis with the addition of rescue antiemetics [Citation12].

The observation phases were defined as follows: overall, from the first day of chemotherapy to day 10; early, from the first day of chemotherapy to 24 h after the last chemotherapy administration (day 6); delayed, from 24 h after the last chemotherapy administration (day 7) to day 10.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 82 patients were included in the analysis. The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in . There were 52 men and 30 women, and the median age was 63 years old (range, 18–85). Sixty-one patients (74%) received full-dose ESHAP. The most common diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, 65%), and 63 patients (77%) received rituximab (375 mg/m2) – combined ESHAP.

Table 2. Patient and treatment characteristics.

Efficacy endpoints

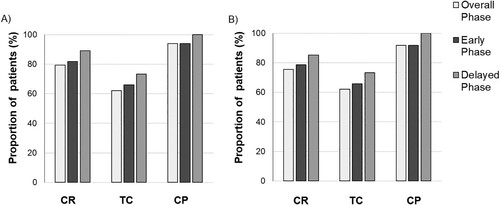

Antiemetic efficacy endpoints are shown in . Among all patients, CR was achieved in 65 patients (79%) in the overall phase. Regarding the efficacies based on the phases, CR was achieved in 67 patients (82%) during the early phase and 73 patients (89%) in the delayed phase. TC and CP were achieved in 51 patients (62%) and 77 patients (94%) in the overall phase ((A)). No patient had a change in their planned cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy schedule due to CINV. Among patients receiving full-dose ESHAP therapy (n = 61), CR was achieved in 46 patients (75%) in the overall phase, 48 patients (79%) in the early phase and 52 patients (85%) in the delayed phase ((B)).

Figure 1. The rates of antiemetic efficacy endpoints. Total control (TC), complete response (CR) and complete protection (CP) in early, delay and overall phase (A) in all patients (n = 82) and (B) in patients receiving full-dose ESHAP (n = 61).

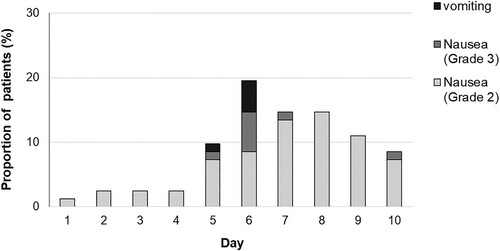

shows a histogram indicating the percentage of patients who had emetic episodes on days 1 through 10. There were only 5 patients (6%) with emetic episodes on days 5–6 and 23 patients (28%) had at least 1 episode of Grades 2–3 nausea. Most of the patients reported nausea on days 4–10 (93% of all episodes).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we demonstrated that ondansetron effectively prevented CINV with a CR of 79% in patients receiving ESHAP chemotherapy, which consisted of 4-day continuous cisplatin infusion with high-dose methylprednisolone, etoposide and cytarabine. Because of this high level of efficacy, our results strongly suggest that NK1RA is not routinely necessary as a prophylactic antiemetic for ESHAP chemotherapy.

CINV is one of the most distressing adverse events in patients receiving chemotherapy [Citation13,Citation14], because it can lead to serious medical problems, such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, and prolong the duration of hospitalization, resulting in increasing treatment costs and impaired quality of life for patients and their caregivers [Citation2]. Therefore, proper management of CINV is essential. The antiemetic guidelines for chemotherapy categorize cisplatin as a highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) agent, and thus an ESHAP regimen that includes 4-day cisplatin is classified as a regimen with high-emetic risk. Therefore, these guidelines recommend an antiemetic regimen consisting of NK1RA, 5-HT3RA and dexamethasone as the standard in patients receiving an HEC such as cisplatin [Citation4]. Moreover, some guidelines recommend the use of olanzapine in addition to this combination [Citation5,Citation6]. However, the emetic risk of multi-day combination chemotherapy has not been fully assessed. In fact, there have been only a few studies evaluating the antiemetic protocol for multi-day cisplatin regimens [Citation15–17]. One of the studies prospectively compared aprepitant with placebo in combination with 5-HT3RA and dexamethasone in patients receiving a 5-day cisplatin-containing regimen for germ cell tumor; the results showed a significantly higher CR with aprepitant (42% vs. 13%) [Citation17].

Based on our long-term experiences of ESHAP chemotherapy chosen as the salvage treatment for malignant lymphoma, we had the impression that ESHAP has a low incidence of nausea and vomiting under the prophylaxis with 5-HT3RA alone. Therefore, NK1RA was not routinely given as a prophylactic antiemetic for patients receiving ESHAP at our institute. Again, based on our experiences, we hypothesized that because ESHAP chemotherapy includes a high dose of methylprednisolone, which itself has an antiemetic effect, ESHAP might not be categorized as having high-emetic-risk. In fact, our study suggested that a 5-HT3RA, ondansetron, effectively prevented CINV in patients receiving ESHAP chemotherapy. As compared to a previous study evaluating the efficacy of aprepitant for a cisplatin-containing regimen (CR, 42%) [Citation17], the CR of 79% in our study was notably higher. Methylprednisolone has been used as a single-agent therapy and in combination with other agents for the prevention of CINV [Citation10,Citation11]. Before the introduction of 5-HT3RA, the combination of corticosteroid with high-dose metoclopramide and diphenhydramine or lorazepam was one of the standard antiemetic regimens for CINV [Citation18]. ESHAP includes intravenous methylprednisolone at a dose of 500 mg on days 1–5, which is the optimal dose for antiemetic effect [Citation19]. In general, a single-agent 5-HT3RA regimen was insufficient for CINV in patients with cancers receiving moderate or high emetic chemotherapy [Citation2,Citation20]. However, most of the chemotherapy regimens for lymphoid malignancies include corticosteroid as an antineoplastic agent, and such a high-dose corticosteroid may also be responsible for the amelioration of CINV in these regimens.

Aprepitant is known to be a CYP3A4 inhibitor and has the potential to interact with variety drugs, including corticosteroid. Therefore, the dose of dexamethasone is decreased in combination with aprepitant as an antiemetic [Citation21]. In addition, it is known that aprepitant increases the area under the blood concentration time curve (AUC) of methylprednisolone [Citation22]. Physicians should also pay attention to the possible interaction with other drugs when using NK1RA. Based on the low risk of CINV and possible drug interaction, it is plausible to avoid the routine use of prophylactic NK1RA as an antiemetic for ESHAP chemotherapy, and possibly for other regimens containing corticosteroid.

In the present study, the majority of nausea and vomiting episodes were observed later than day 4. It is known that ondansetron and dexamethasone effectively relieved acute CINV but had a limited effect on delayed CINV [Citation23–25]. In contrast, NK1RA has been reported to prevent both acute and delayed CINV [Citation26,Citation27]. However, the incidence and severity of CINV were low even in our patients in the delayed phase, which does not reinforce the routine prophylactic use of NK1RA. In such patients developing clinically problematic CINV in the first course of ESHAP, prophylactic NK1RA should be considered for the subsequent courses.

This study has limitations. First, we used only 4 mg/day of ondansetron, a lower dose than the international standard, because of the insurance in Japan. Second, the number of subjects was small and it was a single-arm design. Third, this study was retrospective in nature, and thus a prospective study will be required to clarify the necessity of NK1RA as an antiemetic for ESHAP chemotherapy. Forth, we evaluated only first cycle of chemotherapy in this study. Finally, the doses of chemotherapeutic agents were reduced in a proportion of patients, although the analysis was also performed in patients receiving full-dose chemotherapy.

In conclusion, our results suggested that ondansetron without 5-HT3RA effectively prevented acute and delayed emesis induced by ESHAP chemotherapy. The chemotherapy regimens containing high-dose corticosteroid, which are mostly used for lymphoid malignancies, may present different emetic risks, and thus a future evaluation of the optimal antiemetic protocol for each regimen is warranted.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Keio University School of Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all paramedic staff members at Keio University Hospital for their excellent care of the patients and their families.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sharma R, Tobin P, Clarke SJ. Management of chemotherapy-induced nausea, vomiting, oral mucositis, and diarrhoea. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:93–102.

- Schnell FM. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the importance of acute antiemetic control. Oncologist. 2003;8:187–198.

- Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Weaver CB, et al. Rankings and symptom assessments of side effects from chemotherapy: insights from experienced patients with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:219–227.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Antiemesis. version 2. (2020). Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ antiemesis.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al. Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3240–3261.

- Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J, et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2006;27(suppl 5):v119–v133.

- Velasquez WS, McLaughlin P, Tucker S, et al. ESHAP–an effective chemotherapy regimen in refractory and relapsing lymphoma: a 4-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1169–1176.

- Wang WS, Chiou TJ, Liu JH, et al. ESHAP as salvage therapy for refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Taiwan experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:33–37.

- Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline for antiemetics in oncology: update 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2932–2947.

- Grunberg SM. Antiemetic activity of corticosteroids in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy: dosing, efficacy, and tolerability analysis. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:233–240.

- Hashimoto H, Abe M, Tokuyama O, et al. Olanzapine 5 Mg Plus standard antiemetic therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (J-FORCE): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:242–249.

- Giralt SA, Mangan KF, Maziarz RT, et al. Three palonosetron regimens to prevent CINV in myeloma patients receiving multiple-day high-dose melphalan and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:939–946.

- Cohen L, de Moor CA, Eisenberg P, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and impact on patient quality of life at community oncology settings. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:497–503.

- Navari RM, Aapro M. Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1356–1367.

- Olver IN, Grimison P, Chatfield M, et al. Results of a 7-day aprepitant schedule for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in 5-day cisplatin-based germ cell tumor chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1561–1568.

- Adra N, Albany C, Brames MJ, et al. Phase II study of fosaprepitant + 5HT3 receptor antagonist + dexamethasone in patients with germ cell tumors undergoing 5-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a Hoosier cancer research network study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2837–2842.

- Albany C, Brames MJ, Fausel C, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III cross-over study evaluating the oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant in combination with a 5HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone in patients with germ cell tumors receiving 5-day cisplatin combination chemotherapy regimens: a hoosier oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3998–4003.

- Del Favero A, Roila F, Tonato M. Reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Current perspectives and future possibilities. Drug Saf. 1993;9:410–428.

- Pieters RC, Vermorken JB, Gall HE, et al. A double-blind randomized crossover study to compare the antiemetic efficacy of 250 mg with 500 mg methylprednisolone succinate (Solu-Medrol) as a single intravenous dose in patients treated with noncisplatin chemotherapy. Oncology. 1993;50:316–322.

- Chevallier B, Marty M, Paillarse JM. Methylprednisolone enhances the efficacy of ondansetron in acute and delayed cisplatin-induced emesis over at least three cycles. ondansetron study group. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:1171–1175.

- Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, et al. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to Standard Antiemetic Therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003;97:3090–3098.

- McCrea JB, Majumdar AK, Goldberg MR, et al. Effects of the neurokinin1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on the pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone and methylprednisolone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:17–24.

- Latreille J, Pater J, Johnston D, et al. Use of dexamethasone and Granisetron in the control of delayed emesis for patients who receive highly emetogenic chemotherapy. National cancer institute of Canada clinical trials group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1174–1178.

- Goedhals L, Heron JF, Kleisbauer JP, et al. Control of delayed nausea and vomiting with granisetron Plus Dexamethasone or Dexamethasone alone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, comparative study. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:661–666.

- Tsukada H, Hirose T, Yokoyama A, et al. Randomised comparison of ondansetron Plus dexamethasone with Dexamethasone alone for the control of delayed cisplatin-induced emesis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2398–2404.

- Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, et al. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin–the aprepitant protocol 052 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4112–4119.

- Sakurai M, Mori T, Kato J, et al. Efficacy of aprepitant in preventing nausea and vomiting due to high-dose melphalan-based conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:457–462.