ABSTRACT

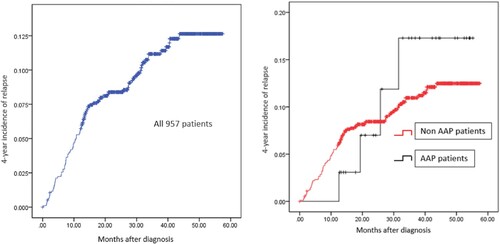

Asparaginase-associated pancreatitis (AAP) is a common and fatal complication after ASNase treatment in acute lymphoblastic leukemia(ALL). Here, a total of 1063 pediatric ALL patients treated with SCCLG-ALL-2016 regimen were collected since October 2016 to June 2020, including 35 patients with AAP. The clinical characteristics of AAP and non-AAP patients were compared. In AAP patients, the possible factors that affected the recurrence of AAP were analyzed, and the possible risk factors related to ALL-relapse were discussed. The results showed that age was a risk factor (P = .017) that affect the occurrence of AAP. In AAP patients, AAP tended to develop after the second use of PEG-ASNase (25.71%). In the follow-up chemotherapy, 17 patients re-exposed to ASNase and 7 cases developed AAP again with a percentage was 41.2%. There were no special factors that related with the recurrence of AAP. This study also found no association between the occurrence of AAP and prognosis of ALL, with the 4-year incidence of ALL relapse in AAP and non-AAP patients were 15.9% v.s.11.7% (HR: 1.009, 95% CI:0.370–2.752, P = .986), and there were no special factors that related with the ALL relapse among AAP patients. Based on the above results, the occurrence of AAP is related to age and should be vigilant after the second use of PEG-ASNase after use in pediatric ALL patients. Moreover, AAP is not associated with ALL relapse, but there is a high AAP recurrence rate when re-exposure to ASNase.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignant tumor in childhood. Asparaginase (ASNase) is one of the key drugs in the chemotherapy regimen for this disease, and asparaginase-associated pancreatitis (AAP) is a common and fatal complication after ASNase treatment. In recent years, the frequently-used type of ASNase in China is PEG-asparaginase (PEG-ASNase). As a younger member of ASNase, this drug has shown many advantages, but the incidence of AAP has not decreased due to its unimproved damage to the pancreas. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 1063 pediatric ALL patients who were admitted to the multicenter study group from October 2016 to June 2020 to explore and summarize the clinical characteristics of AAP.

Method

Patients

South China children’s leukemia Group (SCCLG-ALL-2016 protocol) for the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia in South China was initiated in October 2016 and ended in June 2020. The ages of these patients included in the study ranged from 1.1 to 17.4 years. The diagnostic criteria, protocol, risk grouping and stratification criteria have been described in detail [Citation1]. Definitions and groupings of central nervous system (CNS) diseases and minimal residual diseases (MRD) have also been described [Citation1]. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, and by the ethics committee of other cooperation centers. All patients, or the patients’ parents/guardians, provided written informed consent. The trial is registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Chi-CTR; https://www.chictr.org.cn/; number ChiCTR2000030357).

Application of ASNase in SCCLG-ALL-2016 protocol

The routine use of ASNase in SCCLG-ALL-2016 is an intramuscular injection of PEG-ASNase (2500U/m2/dose), and the frequency is different according to the risk stratification(). Moreover, the dosage of 10.000 IU/m2/every other day, 7 times of application of Erwinia chrysanthemi ASNase (Erwinia) is equivalent to a single application of PEG-ASNase in this study. Based on each cumulated dosage of ASNase, we also divided patients into low ASNase intensity group (the dosage of ASNase was less than 50% of total) and high ASNase intensity group (more than 50%) to explore potential risk factors that might influence the prognosis of patients with AAP. ASNase activity monitoring was not routinely performed in our study.

Table 1. The doses of PEG-ASNase in SCCLG-ALL-2016 protocol.

AAP diagnostic criteria

The AAP diagnostic criteria observed by the collaboration group were as follows [Citation2]. At least two of the following three criteria are to be fulfilled: (i) symptoms of acute pancreatitis, (ii) amylase or lipase levels above three times the upper normal limit, (iii) imaging showing changes consistent with acute pancreatitis. Mild pancreatitis is defined as symptoms lasting <72 h, amylase and/or lipase levels (when measured) below three times the normal upper limit within 72 h, and absence of pseudocysts, bleeding, or necrosis at imaging. Severe AAP [Citation3]: having clinical manifestations and biochemical changes of AP, accompanied with organ failure, or local and/or systemic complications.

Study content and end point

The clinical characteristics of patients with AAP and non-AAP were compared. The disease characters of AAP were summarized. In AAP patients, the possible factors that affected the recurrence of AAP were analyzed, and the possible risk factors related to the prognosis of ALL were discussed.

Patients were followed at initial diagnosis and the study endpoint was the first occurrence of relapse, complete response death (DCR1), secondary malignancy (SMN), loss of follow-up, or June 30, 2021. The primary outcome was the risk of relapse.

Statistics

All data were statistically analyzed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 22.0. Age comparison between groups was performed by independent sample T test. χ2 test was used for counting data. Cumulative incidences of relapse were estimated by Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox proportional-hazards model was used to estimate unadjusted (HR). Two-sided P-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient information

In this study, a total of 1063 pediatric ALL patients treated with SCCLG-ALL-2016 protocol were collected. In total, 957 patients were included in this study, including 35 patients who developed AAP, with an incidence rate of 3.66%, excluding the deaths caused by abandonment during chemotherapy but for AAP. All 957 patients were treated at one of seven pediatric ALL collaborative centers as follows: Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (n = 216), Sun Yat-sen University First Affiliated Hospital (n = 121), Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (n = 58), Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University (n = 158), Guangxi Medical University First Affiliated Hospital (n = 249), Guangzhou First People’s Hospital (n = 21), Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital (n = 134). The comparison of general data between the AAP patients and the non-AAP patients is shown in .

Table 2. The comparison of general clinical information between AAP patients and non-AAP patients.

Clinical features of AAP

We analyzed the occurrent time of AAP and found that 25.71% (9/35) of the patients occurred after the second use of PEG-ASNase, the specific distribution of occurrent time was listed in . The number of days from the usage of PEG-ASNase prior to AAP diagnosis was from 1 to 21 days, with an average of 9.36 ± 5.51 days. The percentage of severe cases was 31.43% (11/35), and 8.57% (3/35) needed insulin treatment. After comprehensive therapy, 31 patients cured with the median course was 13.33 ± 8.35 days (range 3–36 days), 2 patients developed pancreatic pseudocyst, and another 2 severe cases died due to the septic shock with a mortality rate was 5.71%.

Table 3. The distribution of occurrent time among 35 APP patients.

Selection of subsequent chemotherapy regimens in AAP patients

During the subsequent chemotherapy, three patients continued the original regimen, which contains PEG-ASNase and two patients developed AAP again due to the re-exposure. Fourteen cases were changed to Erwinia and only 5 cases developed AAP again. One case had completely finished PEG-ASNase treatment before occurred AAP, 2 cases were subsequently bridged hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) without using ASNase again. The remaining 13 cases also did not receive any type of ASNase in subsequent chemotherapy. Among the 17 patients who used ASNase, the chance of developing AAP again was 41.2%. There had no significant differences in age, sex, risk stratification, AAP severity, and the subsequent type of ASNase between the patients with or without recurrent AAP ().

Table 4. The comparison of possible risk factors that influence the recurrence of AAP among 17 patients who were re-exposed to ASNase.

Cumulative incidences and relapse-specific hazard ratios in total patients.

Median follow-up time for all patients was 52.7 months (range 0.9–57.7 months) until June 30, 2021, 1 developed SMN, 58 got relapse with a 4-year incidence of relapse was 11.9%, the relapse-specific HR comparing HR group patients with non-HR group was 0.269 (95% CI: 0.179–0.402, P = .000), confirming that risk stratification was a definite risk factor for ALL relapse. In addition, the 4-year incidence of relapse in 33 patients with AAP (2 deaths were eliminated) was 15.9%, slightly higher than that in non-AAP patients (11.7%) () with relapse specific HR was 1.009 (95% CI: 0.370–2.752, P = .986), suggesting that occurrence of AAP is not a risk factor for relapse in pediatric ALL patients.

Prognostic factors in AAP patients

Among the 33 patients with AAP (2 deaths were eliminated), 21 cases were in the high ASNase intensity group and 10 in the low group according to each cumulated dosage of ASNase. The average of ASNase doses in the low-intensity group was 1.9, which was significantly lower than the 5.7 doses in high-intensity group (P = .000). Cox proportional-hazards model analysis showed that whether ASNase intensity, risk stratification, hyperglycemia, severity of AAP, recurrence of AAP or bridging HSCT were not associated with the occurrence of ALL-relapse in AAP patients ().

Table 5. The possible risk factors that influence the ALL-relapse among 33 AAP patients analyzed by Cox proportional-hazards model.

Discussion

Asparagine (ASN) is one of the important amino acids required for protein synthesis in the body. By hydrolyzing ASN in blood, ASNase leads to protein synthesis disorder in tumor cells and thus inhibiting the growth of tumor. But excessive decomposition of ASN by ASNase can lead to pancreatic injury and even lead to systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Although the mechanism of AAP is still unclear, statistics show that the incidence of AAP as high as 2–18% [Citation4] during the period of chemotherapy. In our study, the incidence of AAP in 957 pediatric ALL patients was 3.66%, which is consistent with those reports.

Oparaji et al. [Citation5] screened 10 studies that met statistical standards from 1842 articles that explored the risk factors of AAP and believed that there were four potential risk factors for AAP: age, ASNase type, risk stratification, and ASNase dosage. Barry [Citation6], Kearney [Citation7] and Samarasinghe [Citation8] found that the incidence of AAP in ALL who were older than 10 years on initial diagnosis was about 2–2.5 times higher than in patients with younger age. However, a few studies [Citation2,Citation9] believe that the occurrence of AAP has no relation with age. In addition, some studies [Citation8–12] suggested that risk stratification, type and dosage of ASNase may also affect the occurrence of AAP. Our study found age is a factor that affects the development of AAP(P = .016), but other factors (P > .05). In addition, the sensitive genes in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis have been the focus of research in recent years [Citation13–15]. Genes such as PRSS1, PRSS2, SPINK1, CTRC, CASR, CFTR, CPA1, CLDN2, ASNS and ATF5 that are involved in the progress of pancreatitis [Citation16,Citation17], may predict the onset of AAP.

Benjamin et al. [Citation18] collected the clinical data of 465 pediatric ALL patients with AAP in the large-scale ALL groups and found that 6.45% (30/465) of AAP occurred after the first use of ASNase, and for the PEG-ASNase-related AAP, the median number of days from the last injection prior to AAP diagnosis was 11 (6–14). In our study, AAP was most likely to occur after the second use of PEG-ASNase, and the median number of days after PEG-ASNase injections was 9 days.

In theory, the alteration of chemotherapy regimen due to complications with AAP could affect the prognosis of pediatric ALL patients. In recent years, most studies believe that these patients with APP have a higher risk of relapse than others [Citation19,Citation20], and it is necessary to evaluate their prognosis individually. In our study, the occurrence of AAP did not increase the risk of relapse in ALL and may be due to the lacking of ASNase activity detection. After analyzing the possible factors that might increase the risk of relapse in patients with AAP, we also found no special factors.

Since the occurrence of AAP is related to genetic susceptibility, AAP has a higher risk of recurrence. However, there has an obvious difference in the reported incidence of AAP after re-exposure to ASNase in ALL, ranging from 17% to 63% [Citation2,Citation7,Citation18], which may be related to different ASNase types and dosages. In our study, 41.2% of patients developed AAP again after re-exposure to ASNase. At present, there is no consensus to predict the factors related to the risk of AAP recurrence. Some studies [Citation21] made Machine Learning Models to evaluate the risk of AAP recurrence by combining age, gender, pancreatitis gene polymorphism and other potential risk factors. The successful establishment of this model may provide objective basis for the risk assessment of AAP recurrence.

This study is a multi-center clinical study that included more than 1000 cases, the results are reliable. In addition, we discussed the factors that affect the recurrence of AAP and the prognostic factors of AAP patients, which are rarely reported at present in pediatric ALL patients. Unfortunately, this study possesses several limitations. The sensitive genes in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis and ASNase activity were not routinely detected in all patients, especially the lack of ASNase activity detection may affect the prognostic statistical results.

In conclusion, the occurrence of AAP is related to age and should be vigilant after the second use of PEG-ASNase as well as on the 9th day after use in pediatric ALL patients, genetic testing of pancreatitis and ASNase activity is recommended. In our study, there were no special factors that related to the recurrence of AAP. We also found no association between the occurrence of AAP and prognosis of ALL and no special factors that related with the relapse of ALL among AAP patients. Furthermore, there is a high risk of recurrence when re-exposure to ASNase so the subsequent chemotherapy regimen should be adjusted carefully.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Datum of cases used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Li XY, Li JQ, Luo XQ, et al. Reduced intensity of early intensification does not increase the risk of relapse in children with standard risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia – a multi-centric clinical study of GD-2008-ALL protocol. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):59.

- Raja RA, Schmiegelow K, Albertsen BK, et al. Asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in the NOPHO ALL 2008 protocol. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(1):126–133.

- Pancreas Study Group. Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Pancreatology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Digestion. Chinese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis (Shenyang, 2019). J Clin Hepatol. 2019;35(12):2706–2711.

- Judy-April O, Fateema R, Debra O, et al. Risk factors for asparaginase-associated pancreatitis a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):907–913.

- Oparaji JA, Rose F, Okafor D, et al. Risk factors for asparaginase-associated pancreatitis: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(10):907–913.

- Barry E, DeAngelo DJ, Neuberg D, et al. Favorable outcome for adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Consortium Protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(7):813–819.

- Kearney SL, Dahlberg SE, Levy DE, et al. Clinical course and outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and asparaginase-associated pancreatitis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(2):162–167.

- Samarasinghe S, Dhir S, Slack J, et al. Incidence and outcome of pancreatitis in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated on a contemporary protocol, UKALL 2003. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(5):710–713.

- Treepongkaruna S, Thongpak N, Pakakasama S, et al. Acute pancreatitis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(11):812–815.

- Alvarez OA, Zimmerman G. Pegaspargase-induced pancreatitis. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;34(3):200–205.

- Place AE, Stevenson KE, Vrooman LM, et al. Intravenous pegylated asparaginase versus intramuscular native Escherichia coli L-asparaginase in newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (DFCI 05-001): arandomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1677–1690.

- Kurtzberg J, Asselin B, Bernstein M, et al. Polyethylene Glycol-conjugated L-asparaginase versus native L-asparagi-nase in combination with standard agents for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in second bone marrow relapse: a Children’s Oncology Group Study (POG 8866). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(8):610–616.

- Abaji R, Gagné V, Xu CJ, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identified genetic risk factors for asparaginase-related complications in childhood ALL patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43752–43767.

- Wolthers BO, Frandsen TL, Patel CJ, et al. Trypsin-encoding PRSS1-PRSS2 variations influence the risk of asparaginase associated pancreatitis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a ponte di legno toxicity working group report. Haematologica. 2019;104:556–563.

- Liu C, Yang W, Devidas M, et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for acute pancreatitis in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2133–2140.

- Zator Z, Whitcomb DC. Insights into the genetic risk factors for the development of pancreatic disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:323–336.

- Youssef YH, Makkeyah SM, Soliman AF, et al. Influence of genetic variants in asparaginase pathway on the susceptibility to asparaginase-related toxicity and patients’ outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2021;88(2):313–321.

- Wolthers BO, Frandsen TL, Baruchel A, et al. Asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an observational Ponte di Legno Toxicity Working Group study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1238–1248.

- Gottschalk Højfeldt S, Grell K, Abrahamsson J, et al. Relapse risk following truncation of pegylated asparaginase in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(17):2373–2382.

- Gupta S, Wang C, Raetz EA, et al. Impact of asparaginase discontinuation on outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(17):1897–1905.

- Nielsen RL, Wolthers BO, Helenius M, et al. Can machine learning models predict asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2022;44(3):e628–e636.