ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are at higher risk of developing secondary malignancies. In this study, we focused on patients with MPNs that complicated lymphoid neoplasms. To analyze the real-world status of lymphoid neoplasm treatment in patients with pre-existing MPNs in Japan, we conducted a multicenter retrospective study.

Methods:

Questionnaires were sent to collect the data on patients who were first diagnosed with either polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia or myelofibrosis and who later were complicated with lymphoid neoplasms defined as malignant lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small cell lymphoma.

Results:

Twenty-four patients with MPNs complicated by lymphoid neoplasms were enrolled (polycythemia vera, n = 8; essential thrombocythemia, n = 14; and primary myelofibrosis, n = 2). Among these, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) was the most frequently observed (n = 13, 54.1%). Twelve (92.3%) of the patients with DLBCL received conventional chemotherapy. Among these 12 patients, regarding cytoreductive therapy for MPNs, 8 patients stopped treatment, one continued treatment, and two received a reduced dose. Consequently, most patients were able to receive conventional chemotherapy for DLBCL with a slightly higher dose of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support than usual without worse outcomes. All 3 patients with multiple myeloma received a standard dose of chemotherapy.

Conclusion:

Our data indicate that if aggressive lymphoid neoplasms develop during the course of treatment in patients with MPNs, it is acceptable to prioritize chemotherapy for lymphoma.

Introduction

Patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), a classification of chronic hematologic neoplasms characterized by overproduction of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, usually have a prolonged disease course. During the clinical course, 10% of patients with MPNs develop secondary malignancies that can cause death [Citation1]. Although solid tumors are more common secondary malignancies, some patients have complicated hematologic malignancies, including lymphoid neoplasms. A study from Italy showed that patients with MPNs had a 2.79-fold higher risk of developing lymphoid neoplasms than the general Italian population [Citation2]. Another report from Italy also showed a 3.44-fold increased risk of lymphoid neoplasms in patients with MPNs and implied that JAK2V617F mutated patients (5.46-fold) and males (4.52-fold) were at a significantly increased risk [Citation3]. Similarly, patients with MPNs in the United States of America have been shown to have a higher cumulative incidence of lymphoid neoplasms than the general population with a 3.14-fold higher risk for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), a 2.27-fold higher risk for non-HL and a 1.55-fold higher risk for multiple myeloma (MM) [Citation4].

The treatment strategy for MPNs is to prevent thrombotic events and disease progression. Patients with low-risk PV or low-risk ET are mainly treated with low-dose aspirin, whereas patients with high-risk PV or high-risk ET are treated with cytoreductive agents and low-dose aspirin. However, both cytoreductive and low-dose aspirin therapies for MPNs can interfere with the treatment of lymphoid neoplasmsfor example, owing to platelets and/or granulocytes limits. From a single-center experience, three patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) complicated by aggressive lymphomas received chemotherapy for malignant lymphomas (ML) and achieved not only complete response (CR) in ML but also partial response (PR) in MPNs even after the discontinuation of chemotherapy [Citation5]. Although this report showed that chemotherapy for ML could be beneficial for MPNs, the optimal treatment for lymphoid neoplasms in patients with MPNs remains to be elucidated because of the small number of such patients. Considering this background, we investigated the real-world status of treatment for lymphoid neoplasms that develop during the course of MPNs in Japan.

Methods

Patients aged ≥20 years who were first diagnosed with polycythemia vera (PV), ET, or myelofibrosis (MF) and later complicated with lymphoid neoplasms (defined as ML, MM, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small cell lymphoma [CLL/SLL]) between January 2000 and December 2020 were enrolled in this multicenter retrospective study. Questionnaires were sent to collect the following data on MPNs: age at the time of diagnosis, sex, driver gene mutations and other gene mutational status, medical history of other cancers, laboratory data and bone marrow examination data at the time of diagnosis, physical examination findings, details of treatment, incidence of thrombotic or hemorrhagic events, outcomes, and cause of death; and the following data on lymphoid neoplasms: age at the time of diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasms, type and clinical stage, details of treatment, outcomes, and the change in treatment of MPNs during the treatment period of lymphoid neoplasms. The present study was approved by the Institutional Committee of Juntendo University Hospital (20-379) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

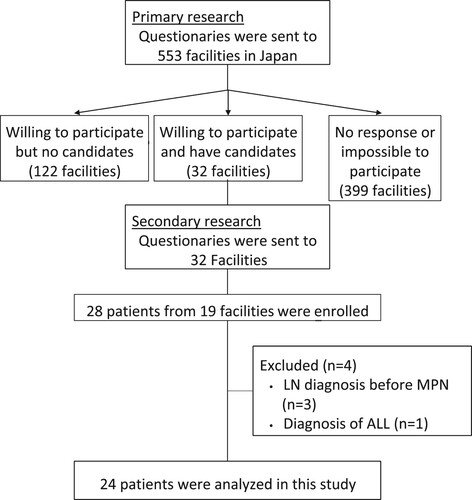

Of the 553 facilities invited to participate in the study, 28 patients from 19 institutions were enrolled in the study (). Among them, three patients who were diagnosed with MPNs after their diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasm and one patient who was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia were excluded. Consequently, the study population included 24 patients: 19 (79.2%) with ML, 4 (16.7%) with MM, including monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), and 1 (4.2%) with CLL/SLL. The clinical features of the patients are presented in . A total of 70.8% (n = 17) of the patients were male, and the median age at diagnosis was 68 years; 17 patients (70.8%) were aged ≥60 years.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients with MPNs and lymphoid neoplasms.

Among the 19 patients with ML, 13 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), 2 had EBV-lymphoproliferative disease (EBV-LPD), 1 had follicular lymphoma (FL), 1 had mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, 1 had lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), and 1 had HL. Fifteen patients received chemotherapy, one received radiation therapy, one received only steroid therapy owing to poor performance status, one was observed, and one died before receiving scheduled chemotherapy due to the deterioration of ML itself.

After a median follow-up of 110.5 (range: 6-275) months (n = 22) since the diagnosis of MPNs, 10 patients died while 12 patients were alive. The outcomes of two patients were unknown. Three and two patients died due to ML and MM, respectively, whereas one patient died due to secondary MF progression from ET. Four patients died from causes other than lymphoid neoplasms or MPNs, including unknown causes of death.

Patients with DLBCL

Thirteen patients were diagnosed with DLBCL, and their clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in and Supplemental Table. A median period of 49 months was noted between the initial diagnosis of MPNs and the subsequent diagnosis of DLBCL. Twelve patients received chemotherapy, including five patients with full dose and seven patients with 50-70% reduced dose. The most common chemotherapy regimen was R-CHOP therapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), followed by R-THP-COP therapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, pirarubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Consequently, 11 patients achieved CR. One patient who did not achieve CR but had progressive disease (PD) and three patients who relapsed after achieving CR underwent second-line therapy. During the chemotherapy period, five patients stopped receiving aspirin, five patients continued, and one patient received a decreased dose of aspirin. No thrombotic events were observed in patients who stopped aspirin therapy. Concerning cytoreductive therapy for MPNs, eight discontinued, while two received a reduced dose, and only one patient continued. Regarding each physician’s experience, although ‘increased frequency’ was not clearly defined, only three patients were thought to have an increased frequency of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) than usual. Four patients required more red blood cell transfusions, and five required more platelet concentrate transfusions. Five patients were considered to have prolonged periods of myelosuppression by their physicians. After a median follow-up of 110 (range: 9-216) months since the diagnosis of MPNs, seven patients died, while six patients were alive. Three patients died of ML.

| (2) | Patients with MM/MGUS | ||||

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients with MPNs and DLBCL

Three patients with ET developed MM and one patient with ET developed MGUS. All three patients with MM received a standard dose of chemotherapy, ending with PD in two patients and PR in one patient. Cytoreductive therapy for MPNs was discontinued during chemotherapy for MM. Two of the three patients with MM received aspirin therapy alone at the time of the diagnosis of MM. One patient discontinued aspirin in preparation to receive chemotherapy for MM, which consisted of melphalan and prednisolone therapy, while one patient continued to take aspirin because of the use of lenalidomide for MM treatment. During their follow-up, two patients died due to MM.

| (3) | Patient with CLL/SLL | ||||

Only one patient with JAK2V617F mutated ET had CLL (stage 1) and did not receive chemotherapy for 36 months after diagnosis.

Discussion

Several reports have shown that patients with MPNs have a 1.4 – to 3.4-fold higher risk of developing lymphoid neoplasms [Citation2–4,Citation6, Citation7]. Masarova et al. reported that 0.3% of patients with MPNs had lymphoproliferative neoplasms [Citation8]. Although they suggested that co-occurrence is rare, it did not appear to predict worse clinical outcomes in patients with MPNs. In Japan, a nationwide survey was conducted to analyze the co-occurrence of ML and myelodysplastic syndromes/MPNs, which showed that a number of patients indeed had both lymphoid and myeloid malignancies, especially those older than 60 years of age [Citation9]. In the present study, we identified 24 patients with MPNs who later developed lymphoid neoplasms. The median age at the diagnosis of lymphoid neoplasms of these patients was 73.5 (range: 59-92) years, as described in a previous study, in which most patients were over 60 years of age [Citation9]. Fifteen of the 19 patients with complicated ML coexisting with MPNs received chemotherapy. Eight patients received chemotherapy at a reduced dose, which could be because their median age was 79.5 (range: 72-92) years, which was older than the overall population (73 [range: 59-92] years, n = 19). As 13 patients received CR with their first-line chemotherapy and only 3 patients died due to ML, these results show that with the discontinuation of cytoreductive therapy for MPNs, most patients were able to receive chemotherapy for ML with a slightly higher dose of G-CSF support, and such patients did not have worse outcomes. Low-dose aspirin was not always discontinued, but did not cause any thrombotic events, suggesting that we should decide whether to continue aspirin according to each patient’s condition.

Among the four patients with complicated MM/MGUS who all had background ET, two patients died of MM. Regarding the benign characteristics of ET against the more aggressive characteristics of incurable MM, this suggests that treatment for MM should be prioritized in this situation. As CLL/SLL is a rare disease in Japan compared to that in Western countries, only one patient had CLL/SLL, and this patient did not require therapy. However, reports from other countries have shown that co-occurrence of MPNs and CLL/SLL could also occur, as in patients with other lymphoid neoplasms [Citation2].

Cytoreductive therapy for MPNs can trigger the development of secondary malignancies. In a large international nested case–control study including 1,881 patients with MPNs, it was shown that some agents (e.g. hydroxyurea, pipobroman, ruxolitinib, and a combination of these agents) could be associated with a higher risk of non-melanoma skin cancer [Citation10]. However, these agents were not associated with a higher risk of hematologic malignancies than in unexposed patients. Porpaczy et al. reported that patients with MPNs treated with JAK inhibitors have a 15 – to 16-fold increased risk of developing B-cell lymphoma compared to those receiving conventional treatment [Citation11]. In contrast, Pemmaraju et al. showed no significant difference in the incidence of secondary lymphoma with or without prior JAK inhibitor treatment [Citation12]. In our study cohort, five patients received JAK inhibitor therapy, while 20 patients received hydroxyurea therapy, including four patients with both JAK inhibitor and hydroxyurea. However, it was difficult to determine any effects of JAK inhibitor treatment in our study because of the small sample size.

A nationwide study of ET and PV in Japan, which included 1,152 and 596 patients, respectively, showed that 36 (3.1%) and 27 (4.5%) patients were complicated with secondary malignancies after their diagnosis of MPNs [Citation13,Citation14]. Among these patients, 6 (0.5%) and 4 (0.7%) patients had complications with ML. In addition, 7 (0.6%) and 11 (1.8%) patients died of secondary malignancies, respectively. Our current study shows that even when patients are complicated by MPNs, chemotherapy for lymphoid neoplasms may continue with the discontinuation of cytoreductive therapy for MPNs.

One limitation associated with this study is the fact that it was a retrospective analysis. In addition, only patients who developed ML during the course of MPNs were enrolled in this study. Therefore, it remains unclear how often patients with MPN in Japan develop ML during the course of their disease. To address this point, a prospective study should be conducted in Japan using a larger cohort in the future, although several other studies have already mentioned a higher incidence of complicated lymphoid neoplasms in a larger cohort than ours [Citation2,Citation4,Citation8]. However, this study revealed the real-world status of treatment for lymphoid neoplasms that develop during the course of MPNs in Japan.

In conclusion, as patients with MPNs have a higher risk of secondary malignancies, including hematologic malignancies, it is important to pay attention to these complications during their long-term clinical course and provide appropriate management. In addition, chemotherapy for lymphoid neoplasms can be prioritized by modifying cytoreductive therapy for MPNs.

Conflict of interest

YE has received grants or contracts from PharmaEssentia Japan K.K., Meiji Seika Pharma Co. and AbbVie G.K.; honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from PharmaEssentia Japan K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Novartis Pharma K.K.; and participated on a advisory board of PharmaEssentia Japan K.K.

TO has received grants or contracts from PharmaEssentia Japan K.K. and Meiji Seika Pharma Co.

YH has received honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Novartis Pharma K.K.

TT has received honoraria for lectures from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., LTD., Novartis Pharma K.K., LTD. and Pfizer Japan Inc; and has received research funding from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., LTD. and Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K.

KU has received research funding from Astellas Pharma Inc., AbbVie G.K., Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., LTD., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., LTD., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Yakult Honsha Co., MSD K.K., Amgen-Astellas Biopharma K.K., Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Incyte Biosciences Japan G.K., Eisai Co., Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., SynBio Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Celgene K.K., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd., Nippon-Shinyaku Co. Ltd., Novartis Pharma K.K., LTD., Mundipharma K.K. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; has served on speakers bureaus for Novartis Pharma K.K., AbbVie G.K., Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Incyte Biosciences Japan G.K., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., LTD., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon-Shinyaku Co. Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc. and Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K.; and has served as a consultant and/or member of an advisory board for Astellas Pharma Inc., Amgen-Astellas Biopharma K.K., Alnylam Japan, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eisai Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., LTD. Ohara Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Sandoz K.K., SynBio Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Nippon-Shinyaku Co. Ltd.

NT has received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Astellas Pharma Inc., Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. and Eisai Co., Ltd.; and has received honoraria directly from an entity from SynBio Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mundipharma K.K. Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Eisai Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. and Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K.

NK has received grants from PharmaEssentia Corp., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Sumitomo Pharma Co., Perseus Proteomics Inc., Kyowa Kirin Co., and Meiji Seika Pharma Co., and honoraria from Novartis Japan, Takeda Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., and PharmaEssentia Corp., and has received a salary from PharmaEssentia Japan where he is a board member.

Acknowledgement

We thank Tomoko Hashimoto for providing secretarial assistance.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Marchetti M, Ghirardi A, Masciulli A, et al. Second cancers in MPN: survival analysis from an international study. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:295–301. doi:10.1002/ajh.25700

- Rumi E, Passamonti F, Elena C, et al. Increased risk of lymphoid neoplasm in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasm: a study of 1,915 patients. Haematologica. 2011;96:454–458. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.033779

- Vannucchi AM, Masala G, Antonioli E, et al. Increased risk of lymphoid neoplasms in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2068–2073. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0353

- Brunner AM, Hobbs G, Jalbut MM, et al. A population-based analysis of second malignancies among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms in the SEER database. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:1197–1200.

- Palandri F, Derenzini E, Ottaviani E, et al. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, methotrexate, bleomicin and prednisone plus rituximab in untreated young patients with low-risk (age-adjusted international prognostic index 0–1) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1824–1824. doi:10.3109/10428190903216796

- Pettersson H, Knutsen H, Holmberg E, et al. Increased incidence of another cancer in myeloproliferative neoplasms patients at the time of diagnosis. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:152–156. doi:10.1111/ejh.12410

- Landtblom AR, Bower H, Andersson TM, et al. Second malignancies in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: a population-based cohort study of 9379 patients. Leukemia. 2018;32:2203–2210. doi:10.1038/s41375-018-0027-y

- Masarova L, Newberry KJ, Pierce SA, et al. Association of lymphoid malignancies and Philadelphia-chromosome negative myeloproliferative neoplasms: Clinical characteristics, therapy and outcome. Leuk Res. 2015;39:822–827. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2015.05.002

- Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Yokoyama Y, Muto H, et al. A nationwide survey of co-occurrence of malignant lymphomas and myelodysplastic syndromes/myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:829–830. doi:10.1007/s00277-016-2612-3

- Barbui T, Ghirardi A, Masciulli A, et al. Second cancer in Philadelphia negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN-K). A nested case-control study. Leukemia. 2019;33:1996–2005. doi:10.1038/s41375-019-0487-8

- Porpaczy E, Tripolt S, Hoelbl-Kovacic A, et al. Aggressive B-cell lymphomas in patients with myelofibrosis receiving JAK1/2 inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2018;132:694–706.

- Pemmaraju N, Kantarjian H, Nastoupil L, et al. Characteristics of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms with lymphoma, with or without JAK inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2019;133:2348–2351. doi:10.1182/blood-2019-01-897637

- Hashimoto Y, Ito T, Gotoh A, et al. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcomes of patients with essential thrombocythemia in Japan: the JSH-MPN-R18 study. Int J Hematol. 2022;115:208–221. doi:10.1007/s12185-021-03253-0

- Edahiro Y, Ito T, Gotoh A et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese patients with polycythemia vera: results of the JSH-MPN-R18 study. Int J Hematol. 2022;116:696–711.